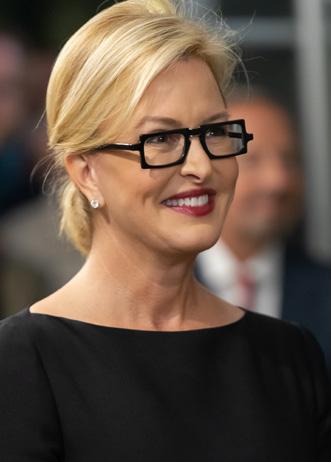

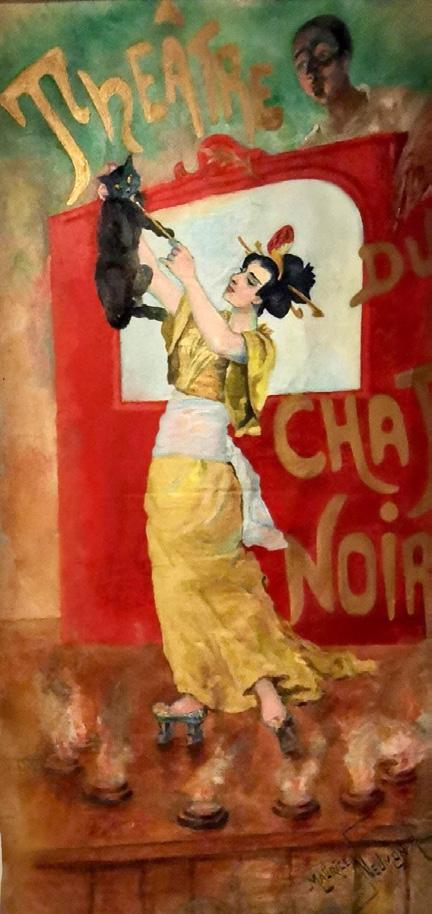

Welcome to AFMM’s Chat Noir - a turn of the century cabaret brilliantly captured in this second edition of Number 12 by our editor in chief, Sophie Evans. We chose to devote this year’s publication to the Chat Noir because the cabaret acts as a perfect microcosm for all that we love about Montmartre. Filled with painters, poets, producers, and musicians, the Chat Noir was overflowing with artistic spirits begging to be imbibed. It was a gathering place, where members of the Parisian bourgeoisie could rough it, shoulder to shoulder with the starving artist. A place to hear Erik Satie long before his “Gymnopédies” entered the mainstream. A place to watch cinema’s early prototype, shadow theater, with its unbridled plots and intricate cutouts. A place to hear and see Aristide Bruant perform in his iconic red scarf, hoping that he doesn’t call you out from the audience! Decorated by Steinlen’s countless cats and moons, this place was magical.

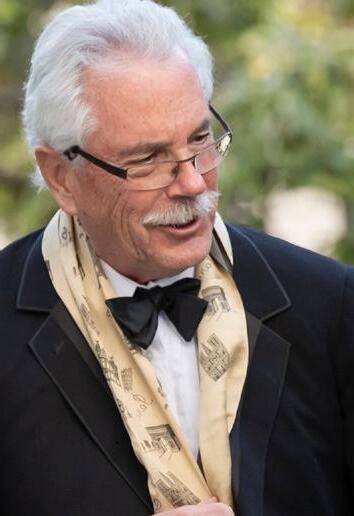

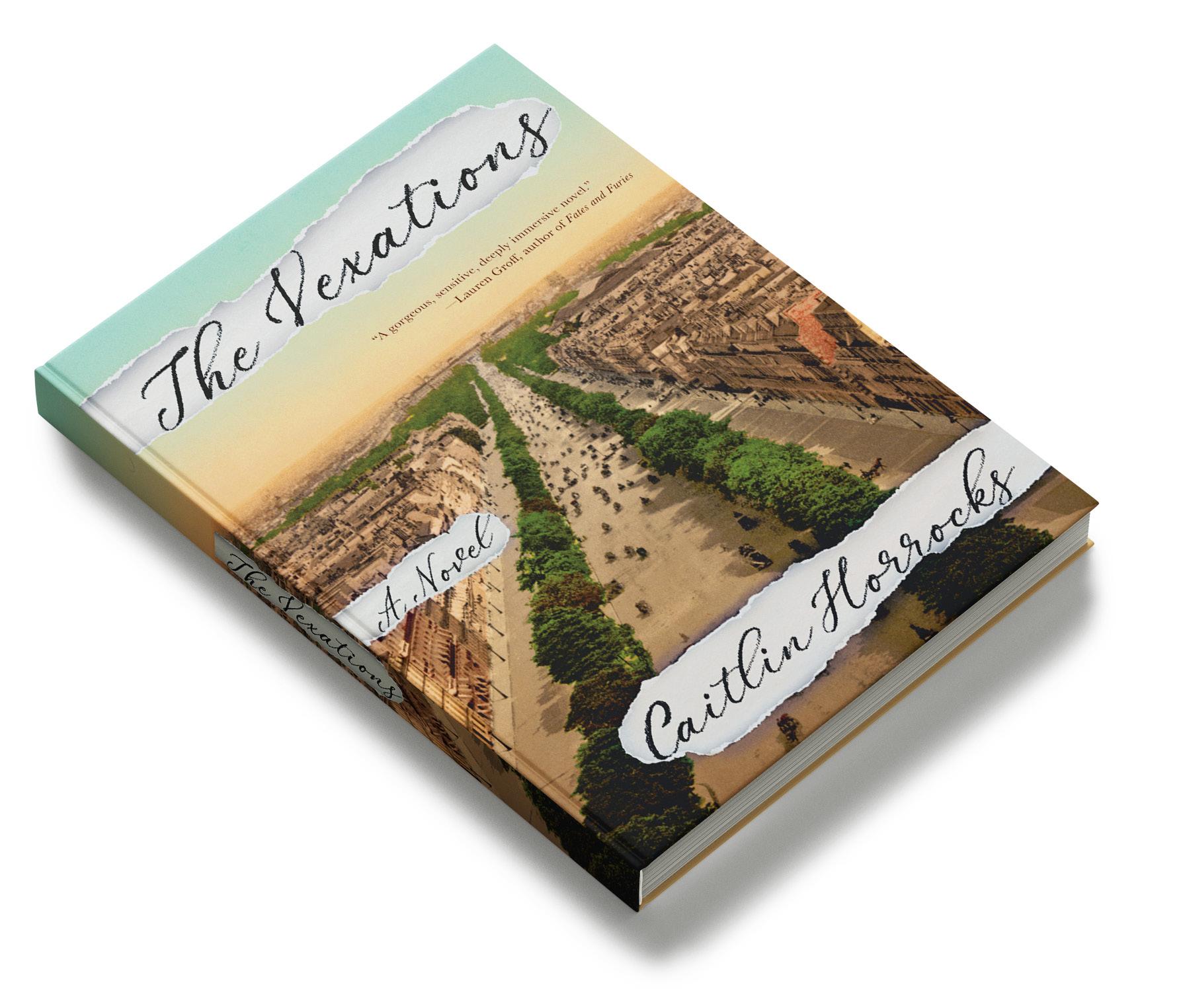

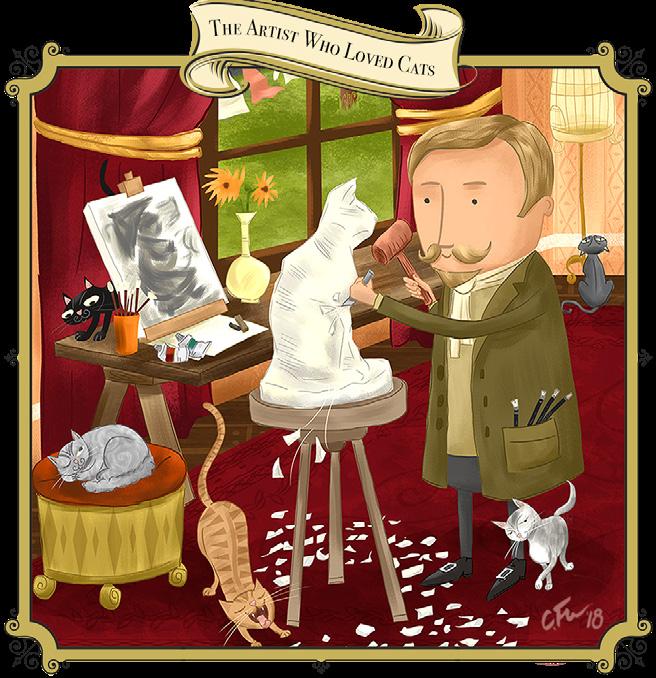

The American Friends was created to uphold the tradition of the Chat Noir, and I’m so happy to share with you that the past year has been full of cabaret spirit, in every sense of the word. In the fall, AFMM Benefactors, Patrons, and Sponsors gathered in Paris, delighting in the Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen exhibition opening party, private tours, cabaret, delicious food, and esprit de corps. Our members support an exhibition each year, and I hope you will be able to visit the Steinlen show before it closes in February 2024. In addition to donating several works to the exhibit, our lovely Tim Hanford shares with this edition of Number 12 his insight into Steinlen’s life and lifelong dedication to cats. It’s a captivating tale also reimagined by fellow AFMM member Susan Bernardo in her children’s book, The Artist Who Loved Cats. Also previewed in this edition is Caitlin Horrocks’ The Vexations, a captivating novel about the dissonant life of Erik Satie - an iconic Montmartre composer and occasional overnight guest at Suzanne Valadon’s apartment, which lives on at the Musée.

Jacqui MICHEL AFMM PRESIDENTIf the Chat Noir is beginning to sound like it was home to a cast of characters, I urge you to read our in house scholar Phillip Dennis Cate’s piece that tells the wonderful story of the cabaret’s very own theater.

During the Chat Noir’s performances, the audience too played a part. As the first act ended, a character announced, “Oh brother, it is the holy hour of Absinth. Let us pray,” signaling that it was time for us to order the drinks that supported the whole operation. With the launch of Number 12 and our new website, americanfriendsmm.com; a newly renovated gallery at the Musée designed by the creative talent Ignasi Cristià; and our ever-growing salons, AFMM is certainly ready to toast our first act. I cannot wait to see what is to come in the company of our new Friends, the American Friends Musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie, Les Amis du Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, the French-American Cultural Foundation, and YOU! As always, membership information can be found on the back cover. Cheers!

Let us pray. ofAbsinth . it is the holy hour Oh brother

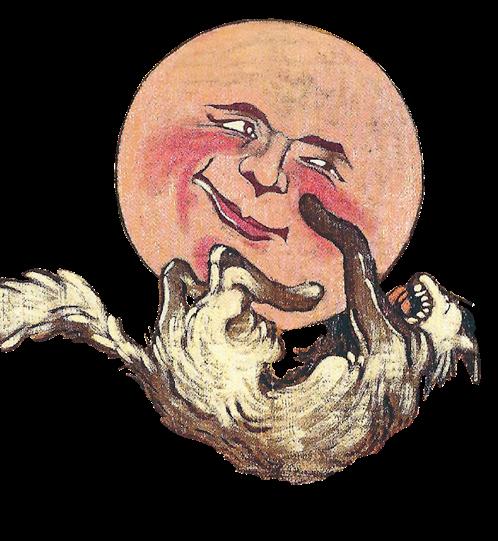

Rodolphe Salis established the first Chat Noir in November of 1881. Billed as a “Louis-XIII style cabaret, founded by a fumiste,” it was located at 84 boulevard Rochechouart in an old post office. Eugène Grasset designed iron chandeliers for an interior inspired by medieval architecture. Adolphe Willette was responsible for the design of the cabaret’s distinctive exterior sign: a black cat on a crescent moon. It

Drawn from Phillip Dennis Cate’s Around the Chat Noir: Arts and Pleasures in Bohemian Montmartre, 1880-1910

was a club like nothing Paris had seen before.

Salis created a fumiste parody on the French Academy’s home on the Left Bank, by naming a back room space “the Institut,” which from then on was reserved solely for the privileged artistic, literary, and musical habitués of the Chat Noir. “Fumisme,” as practiced by the artists and writers who frequented the Chat Noir cabaret, had no social or humanitarian agenda; in fact, the function of “fumisme” was to counteract the pomposity and hypocrisy perceived as characterizing so much of society. In January 1882, Salis began promoting

the cabaret through the Le Chat Noir newspaper: “The Chat Noir is the most extraordinary cabaret in the world. You rub shoulders with the most famous men of Paris, meeting there with foreigners from every country in the globe.... It’s the greatest success of the age! Come on in!! Come on in!!”

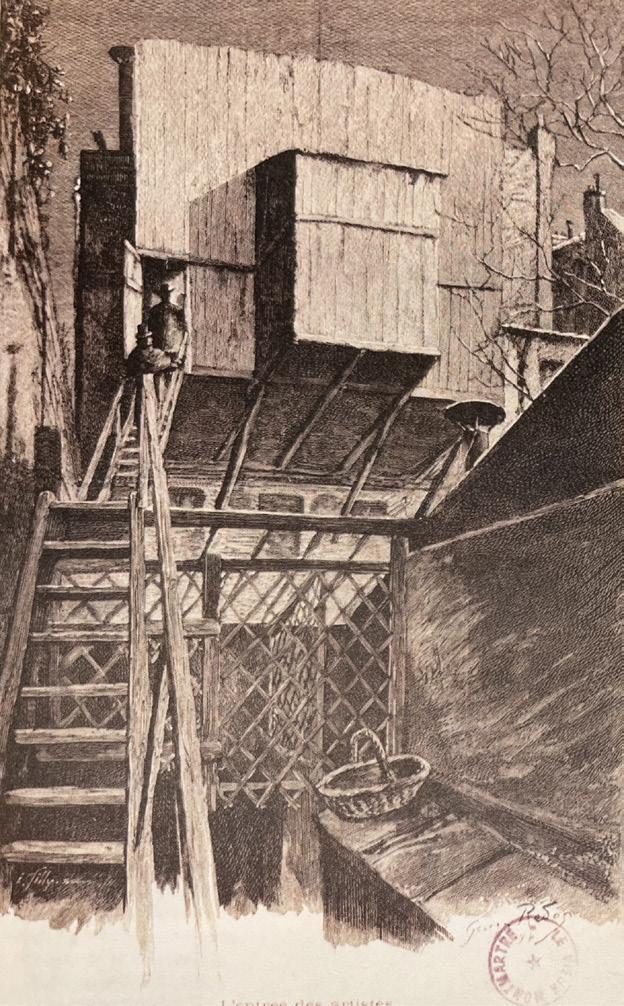

With Salis’s entrepreneurial direction and the fresh talent of writers, artists, and performers, Le Chat Noir and its journal became popular and financial successes. By June 1885, Salis was able to move his operation into an elaborately furnished three-floor venue on Rue Victor Massé (previously Rue de Laval), just a few blocks from the old Chat Noir. At the entrance of the second Chat Noir, a yellow and black sign welcomed potential patrons with the admonition “to be modern.”

Regardless of the complaints of commercialism by Goudeau, Willette, and others, the Chat Noir offered much to the artistic environment of Paris. Perhaps its most important and influential contribution was the cabaret’s sophisticated shadow theater created in 1886 by the artists Henri Rivière and Henry Somm. The shadow theater was to become the greatest realization of the Chat Noir’s exhortation “to be modern.” It began by expanding upon the theatrical possibilities of the small puppet theater that George Auriol and Somm had set up at the Chat Noir the previous year. By the end of 1887, Rivière had transformed the traditional, simple silhouette shadow play normally performed in France as family entertainment, into a highly elaborate, technically complicated

“THE CHAT NOIR IS THE MOST EXTRAORDINARY CABARET IN THE WORLD. YOU RUB SHOULDERS WITH THE MOST FAMOUS MEN OF PARIS, MEETING THERE WITH FOREIGNERS FROM EVERY COUNTRY IN THE GLOBE…”

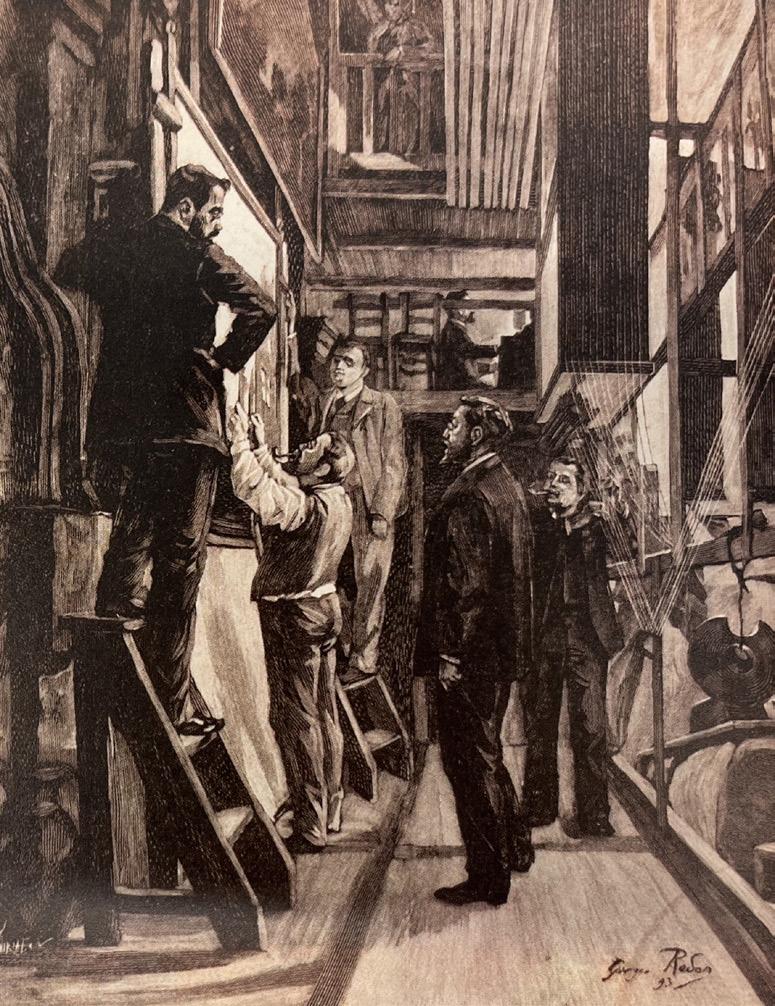

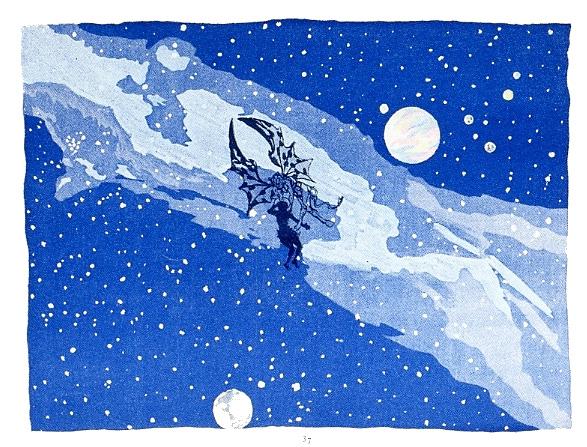

theater production that included all the future components of cinema: movement, color, and sound. The plays produced at the Chat Noir varied from the Napoleonic saga, L’Épopée (1886), and outright fumiste humor in Henry Somm’s Le Fils de l’eunuque (1888), to mixtures of realism and fantasy in Rivière’s La Tentation de Saint Antoine, to the serious symbolist, religious play, La Marche à l’étoile (1890) by Rivière and Georges Fragerolle. Rivière’s elaborate productions demanded the participation of twelve mechanics, as well as friends and colleagues who worked as scriptwriters, singers, musicians, and technical assistants.

He controlled all elements of the production, with no detail escaping him.

Rivière described his invention as follows, “I employ no projections. The oxyhydric light I use burns as an open flame, without a reflector, about three meters from the screen.... Before striking the screen the light passes through three cage-like structures, composed of frames and grooves. Thus imprisoned, it has to go through this tunnel before illuminating the screen. In the first light box can be slid thirty glass sheets, each of a single color. This gives me an initial palette from which, depending on the distance, I select particular tones. The second box, also designed to hold

thirty glass sheets, is used to portray the skies, landscapes, and accessories. By combining these plates with the preceding ones and maneuvering them in different directions, I obtain remarkable shadings: dawns, sunsets, moonrises, delicate mists, and movements of the sea. The third box, higher than the others to accommodate the spread of the light, contains the backgrounds, zinc cutouts set in small frames. It serves to create dense silhouettes: fogs, mountain ranges fading into the horizon. Reflections on water are created by superimposing gauze fabric, the rain is represented with sand, snow with spotted muslin, lightning with nitrated paper that we

set alight and throw. We obtain the movement of the sea with our hands, onto which we attach little fins, of varying shapes; by direct superimposition, we simulate the swell of the waves.

The aesthetics of the Chat Noir shadow theater—in particular, flat silhouettes and subtle abstract color variations—resonated with the nascent modernist concerns of Lautrec, Anquetin, Émile Bernard, Paul Gauguin, Charles Guilloux and, especially, with the future Nabis: Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Félix Vallotton, and Henri Gabriel Ibels. For more than ten years, Rivière’s innovative shadow theater produced over forty plays. It was the cabaret’s star attraction, and during the 1890s Salis’s shadow-theater company toured throughout France and other parts of the world. It was widely imitated at other cabaret artistiques in Montmartre, and in 1897 directly inspired the shadow theater at the Quatre Gats cabaret in Barcelona, which was created by Ramón Casas and Miguel Utrillo and frequented by the young Pablo Picasso.

In the fall of 1893, the Chat Noir opened its new season of shadow

plays with a renovated and enlarged theater with decorative panels by Jules Chéret and color prints by Rivière, Louis Morin, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Auriol. In addition to Willette’s The Golden Calf stained-glass front window, the facade was elaborately decorated by Eugène Grasset, with two fifteenthcentury-style lanterns and an enormous heraldic, bronze black cat surrounded by golden sunbursts. Over the entrance was Willette’s bronze Black Cat on a Half Moon. On the ground floor was a large plaster cast of Houdon’s nude Diane. On the walls of stairwells and of rooms throughout the cabaret were an assortment of antiquities, Japanese masks, portraits of Chat Noir leaders by Antonio de La Gandara, and many of the original drawings for Le Chat Noir newspaper by Salis, Auriol, Rivière, Steinlen, Somm, Caran d’Ache, and numerous other artists.

In the Salle des Fêtes was a group of forty-five drawings, including work by Camille and Lucien Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, and ToulouseLautrec. The Salle des Fêtes housed the shadow theater and accommodated one hundred and fifty guests. In 1893 Grasset redesigned the facade of the theater: framing the screen on the bottom and sides was a painted frieze of cats; hanging over the center was a large plaster head of a black cat, above which were hung eight monochromatic, Japanese-inspired masks by Grasset, representing the major Chat Noir personalities: Salis (yellow); Tinchant (green); Mac-Nab (gray); Caran d’Ache (off-white); Steinlen (blue); Rivière (red); Somm (scarlet); Willette (a “pierrot” white). At the top was Le Chat Noir’s motto: “Montjoye et Montmartre!”

(“Montjoye” is the tongue-in-cheek archaic spelling of “Montjoie,” which is

what French soldiers would shout when going into battle in the Middle Ages. This battle cry also included the name of the saint associated with the ruler. The soldiers of the King of France would shout “Montjoie Saint-Denis!” For the soldiers of the Dukes of Burgundy, the cry was “Montjoie Saint-Andrieu!” and so on, depending on allegiances. In this case, the cry is “Montjoye Montmartre,” which subversively states Le Chat Noir’s allegiance to the Bohemian heart of fin de siècle Paris, the Montmartre area.)

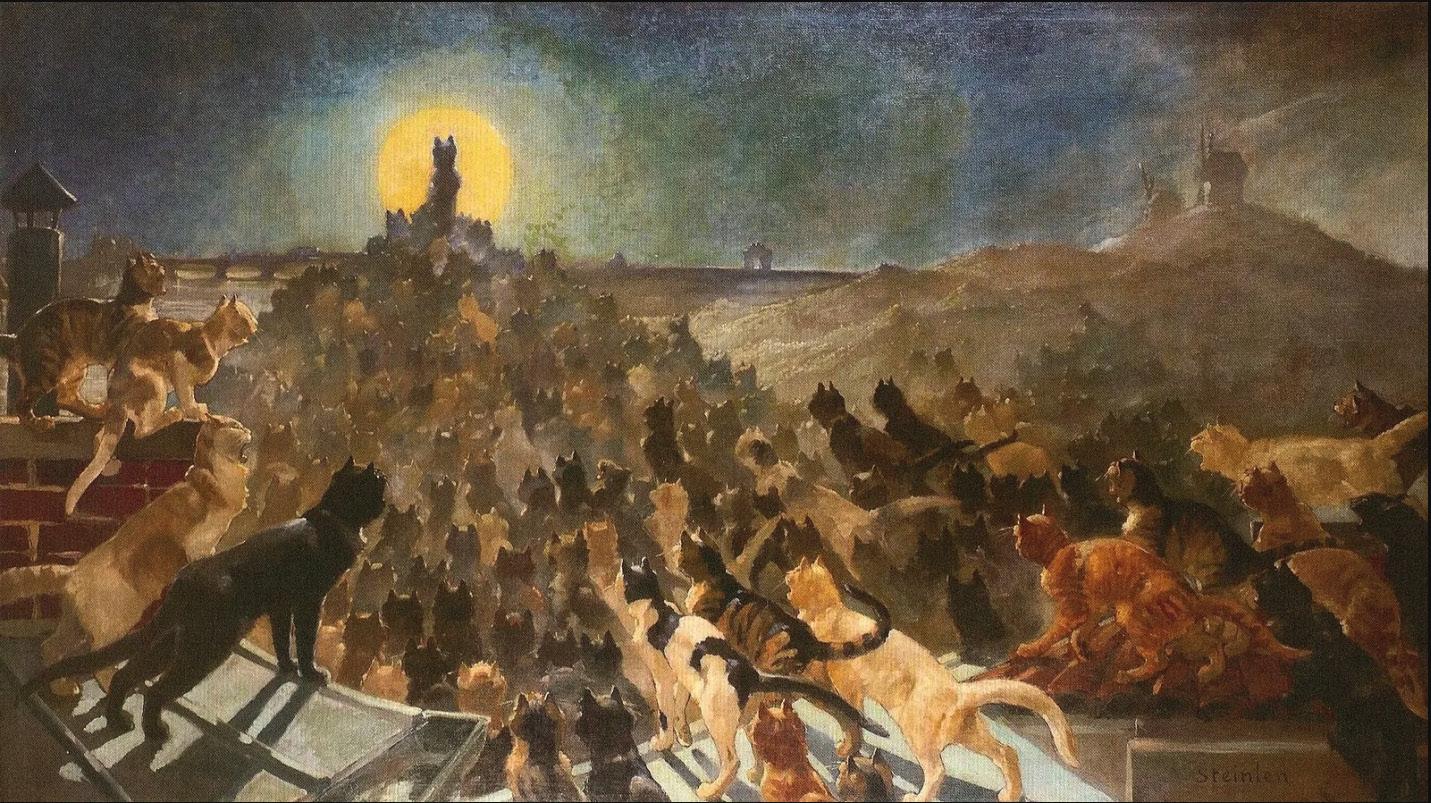

The Salle des Fêtes also contained two of Willette’s designs for the old Chat Noir: Parce Domine, a large allegorical painting of the death of Pierrot, and the oil on canvas study for Willette’s stained glass, The Green Virgin with a Cat. In addition to many drawings, Steinlen was represented by his 10-foot (3-meter) wide mural, The Apotheosis of Cats. In fact, because of the quantity and variety of art in the Chat Noir, it was considered by many of its habitués to be “the Louvre of Montmartre.”

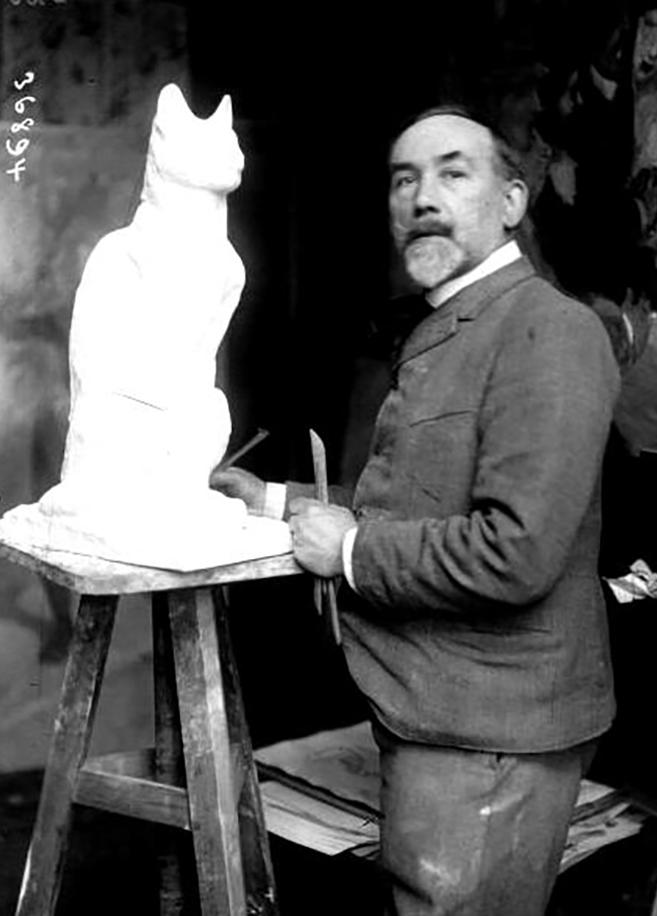

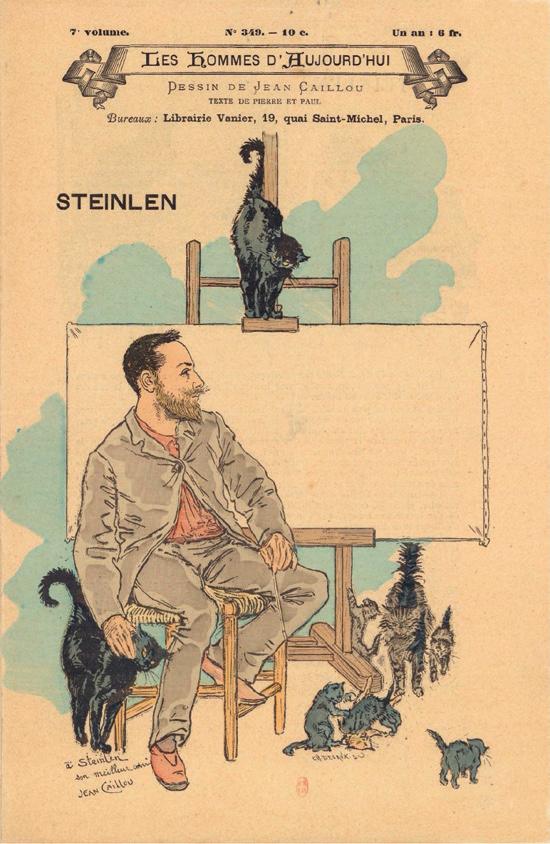

Tim Hanford to introduce you to Théophile Alexandre Steinlen: iconic Montmartre artist, unabashed socialist, celebrated printmaker, and sculptor of cats.

STARTING IN OCTOBER, the Musée de Montmartre is presenting an exciting exhibition of the works of Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (Lausanne 1859 – Paris 1923). The show is partially supported by the American Friends of Musée de Montmartre (AFMM) and includes works from the permanent collection of the museum, from other French and foreign museums, and from private collections. For those of us who serve domestic felines (25% of U.S. households), it is important to note Steinlen’s famous cats will be well represented.

Initially employed as a textile designer in Mulhouse, Steinlen chose to pursue a career in art. He moved to Paris in 1881 and took up residence in Montmartre where he stayed for the rest of his life (and his final repose in the Cimetière St-Vincent just steps from our museum). His prodigious artistic output included paintings, sculptures, posters, drawings, etchings, lithographs, and magazine, music, and newspaper illustrations – for an indication of the breadth of his work, see www.steinlen.net, a site maintained by the author.

Steinlen was a champion of the common man and woman and didn’t hesitate to allow his socialist politics to come through in his work. He gave freely to others but was often short of funds – a surprising circumstance for someone who for a while was the best known artist in Paris (surpassing by reputation even his friend and sometimes competitor Toulouse-Lautrec). A young Pablo Picasso was inspired by Steinlen’s widely circulated periodical illustrations from Gil Blas Illustré (the Picasso Museum in Barcelona holds a scrap of paper from 1899 on which Picasso practiced copying Steinlen’s signature).

After his death, Steinlen’s renown waned. In 1967, he was even included in a catalogue of “Forgotten Printmakers of the 19th Century.” But starting in the late 1970’s, museum shows and catalogues in Europe returned focus to Steinlen. In the following decade, the poster craze of the 1980’s brought renewed attention to Steinlen’s affiche masterpieces. A 1982 exhibition at Rutgers University’s Zimmerli Museum and the accompanying catalogue by current AFMM Advisory Board Member Phillip Dennis Cate served as an important introduction of Steinlen to modern American audiences.

Steinlen’s drawings and prints (other than the posters) remained mostly bargains until 2019 when the Musée d’Orsay pre-empted an auction sale of 50 Steinlen drawings (primarily for Gil Blas Illustré) by paying more than

$500,000 for the collection. Several auctions in the last few years show the Steinlen market remains deservedly strong, but high prices have also attracted the entry of many fakes into the market (caveat emptor).

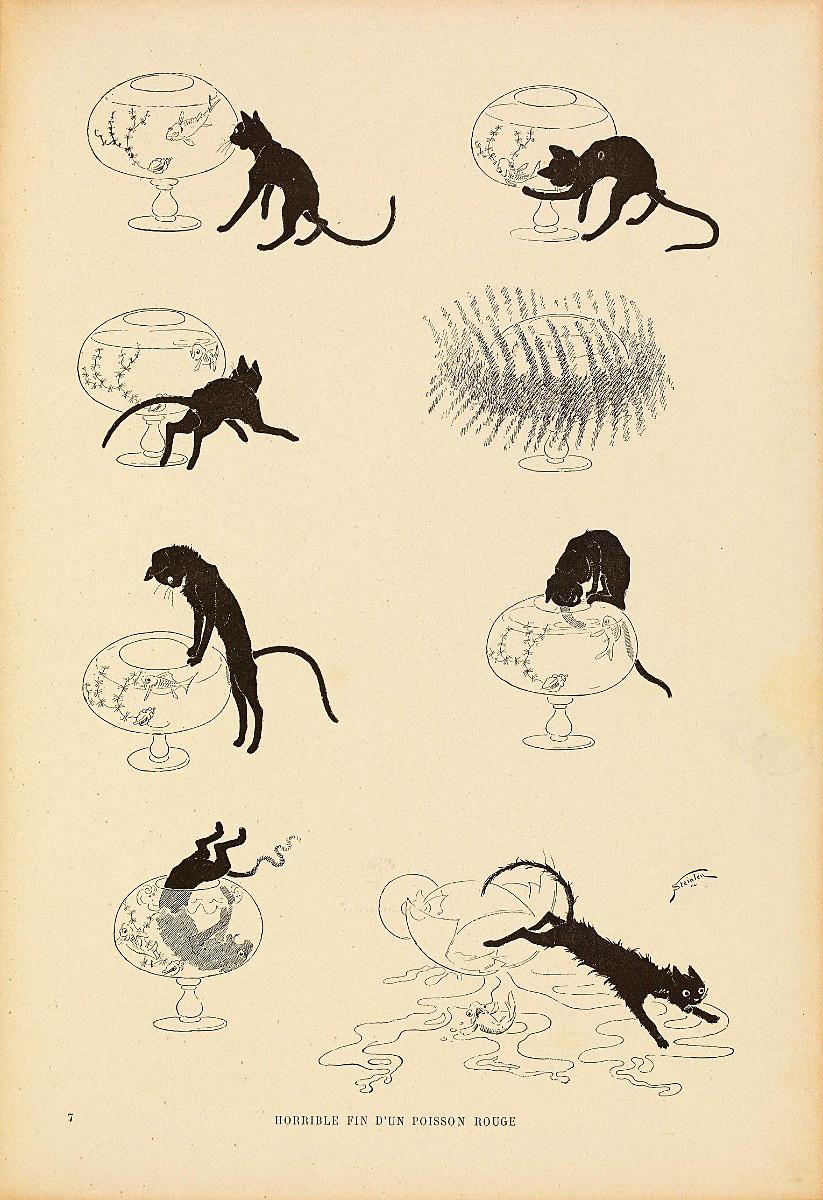

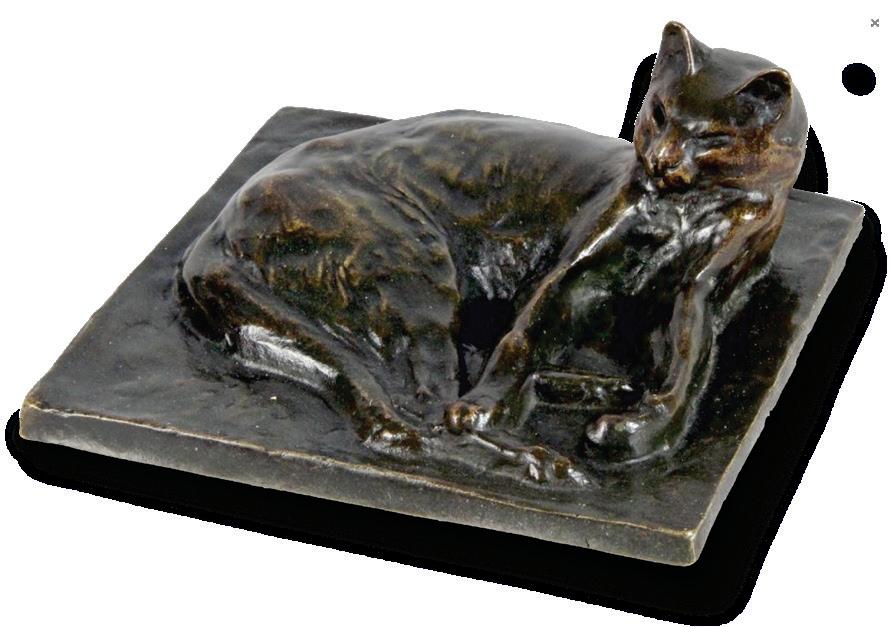

For Steinlen, cats were lifelong companions and models. The house where he lived for many years in Montmartre was known as “Cat’s Cottage” – it still exists hidden behind

more modern buildings on the rue Caulaincourt. Above are a few examples of Steinlen’s cats.

With his love of cats, how could Steinlen not have been attracted to the Chat Noir cabaret (and journal) started in 1881 by fellow Swiss expatriate Rodolphe Salis?

Also above is an cartoon-like illustration for a 1884 edition of the journal, “Horrible end of a Goldfish.” It perfectly embodies the Chat Noir humor.

TheNumber 12 ’s Sophie Evans sat down with CAITLIN HORROCKS to chat about the wonderful eccentricities of composer Erik Satie and the home he made for himself in the Chat Noir. AFMM members joined the duo for a fall salon discussing Caitlin’s recent book, The Vexations.

SOPHIE EVANS: What led you to write a novel about Erik Satie and Montmartre? How did you decide on a work of fiction “governed by facts”? You present us with a plethora of first-person narratives – how did you craft the artists’ internal monologues?

CAITLIN HORROCKS: As a child, I was a mediocre piano student who fell in love with Satie’s “Gymnopédie No. 3.” I started gobbling up Satie pieces, only to quickly realize that most of his work was light on the elegant melancholy of the Gymnopédies, and heavy on playfulness and experimentation. At the time, I didn’t know what to do with this guy who was telling the performer to play “Like a nightingale with a toothache.” My musician-brain was baffled, but my storyteller-brain was intrigued.

As I began researching Satie, I found biographies and works of music theory, but no fiction. “The historian will tell you what happened,” the writer E.L. Doctorow once said. “The novelist will tell you what it felt like.” I wanted to imagine my way into what these lives felt like, to send both myself and the reader on a journey to this other place and time.

I’ve read lots of wonderful historical fiction written at many different angles to fact, and I don’t think there’s necessarily anything wrong with loose inspiration vs. detailed research. But personally, I wanted to color inside the lines, working within the outlines of the historical record. I felt a deep sense of loyalty to the people I was writing about, and wanted to do them justice, but I also knew that I was writing fictional versions of them who would inevitably be different from whoever their real-life selves might have been. It was a complicated balancing act.

SE: Montmartre is often remembered as a place of rich interrelation between artists: painters, poets, composers – they all came together in the cabaret. But Montmartre also had this connection with bourgeois Paris. Satie is a classically trained pianist, but he plays in the cabaret. He has aspirations to write for the Paris Opera House, yet Gymnopedies “premieres” alongside Lou-Lou-Louise. Why? Why look for approval from Aristide Bruant and his audience?

CH: I think Satie regularly felt starved of any and all kinds of approval, and looked for it wherever he thought it might be on offer. He was classically trained, but his grade reports at the

conservatory were lackluster. He was largely self-taught as a composer. He knew from a very early age that he didn’t want to work a conventional job, but his path as an artist wasn’t clear or sure. His work as a cabaret accompanist was a financial necessity, but also made it possible for popular music to influence his classical compositions. When he finally got the opportunity to compose a full-length ballet, the score contained a roulette wheel. His whole career was a kind of improvisation, of fitting together what skills and interests he had, and making new kinds of music out of them, with a gleeful disregard of traditional boundaries between high vs. low, or serious vs. popular music.

SE: How did the bourgeoisie’s desire to “rough it” in Montmartre influence the art and the artists? Did the cabarets cater to particular audiences? To whom did Montmartre belong?

CH: There was a range of cabarets catering to different clienteles and price points and levels of “authenticity”: some had a reputation for pandering to the bourgeoisie, while others remained places where artists valued seeing and being seen, even if there were rich interlopers. Aristide Bruant had experienced real poverty: his performances had an authenticity and grittiness that people flocked to, even as Bruant made it part of his act to openly insult them. But it was definitely an act, with Bruant playing a role calculated to offend-but-not-too-much. In contrast, the poet Jehan Rictus for a time performed his “Soliloquies of the Poor” at the Cabaret des Quat’z’Arts, but his social critique was too direct, and Rictus too angry, unable or unwilling to use humor to make his act more palatable. There were limits to what audiences would accept, and what café owners found commercially viable. The Cabaret des Quat’z’Arts got rid of Rictus pretty quickly.

The question of “To whom did Montmartre belong?” is a fascinating one. While I was working on the novel, I kept thinking about how pretty much everyone’s artistic work took place entirely in commercial establishments. There weren’t welcoming public spaces or state resources that Montmartre’s artists had access to: they were living in hovels owned by private landlords, eating and drinking and working and trying to get warm in bars, cafes, and restaurants all owned by proprietors trying to turn a profit. Pretty much everywhere they went they were asked to pay for the privilege of being there. Some of them paid in work that has

endured, that has become what we picture or hear when we think of this moment in space and time. The artists own our idea of Montmartre now, but I wish they could have owned a little more of the real thing when they were living there.

SE: What did fame mean to Montmartre artists? How did a person’s life differ if they only achieved fame posthumously, as was the case with Satie?

CH: Greater fame would have brought more money, but not necessarily more financial stability. Something I found incredibly poignant in my research, and which only partially made it into the novel (mostly through the character of La Vorace) was how precarious and even harmful success could be, especially for women. If you started to be an audience draw, you’d be asked to finance ever more and fancier costumes, to pay for your own promotional posters, to pay for a horse and carriage to meet you at the stage door, because it wouldn’t do for a “star” to be seen leaving the theater on foot. The performers were asked to shoulder a lot of expenses which took a huge cut of their earnings. In a milieu that really valued novelty, and, for women, youthful beauty, it was virtually impossible to both earn enough and save enough independently to support oneself after audience tastes turned towards something else. Most people were constantly on the look out for some kind of patronage, whether that meant, for a young female dancer, becoming a rich man’s mistress, or for someone like Erik, trying to make connections with wealthy patrons who might commission pieces or just lend him money without much, or any, expectation of repayment.

I think he would have been less desperately poor had he achieved more fame during his life, but I think his money

problems would have persisted. But I also think he would have found greater fame incredibly personally satisfying. I think he would have had a grand time being famous.

SE: In your novel, a poet reflects, “That this cat means anything to anyone, so many years later, is a miracle. There are religions that have not lasted so long. The indelible figure is like a church, a shrine, an altar to his younger self, to all those younger selves, all those eager pilgrims.” Why, do you think, the Chat Noir has endured?

CH: One of the souvenirs my parents brought back from a trip to Paris was a set of coasters emblazoned with the iconic cat from Théophile Steinlen’s 1896 Chat Noir poster. I put drinks on those coasters for years without thinking much about the artist who made the image, or the real place it represented, or what had prompted my parents to select those coasters out of the many gift items Paris has to offer. I suppose we were using the coasters in the same way that it’s easy to enjoy Satie’s “Gymnopédie No. 3”—as evocative background, as overall vibe. Both music and image have such a durable power that you can put them in ads or on coasters, and the magic survives. So in part, I think the endurance of the Chat Noir as a symbol of the entire Montmartre cabaret scene owes a huge debt to this one perfect, beautifully executed visual. But I think it also endures because there’s power and meaning beyond the coaster or poster: we can read and listen and discover and plug into this historical moment of artistic experimentation and energy. While I was writing the book, I felt like the Chat Noir was still a doorway I could walk through, and think about all the people who came this way before me, and wonder what they were looking for.

Around t he Chat No

In t he moonlight ,

I am see king my fortune, At Montm artre in the e vening.

One of our favorite passages from The Vexations follows.

Erik finishes Philippe’s beer and walks to the piano like a man to the guillontine.

As the rest of the seats fill, he studies the folder of music as if it will help him. He wants to announce to the audience that he is really quite well-liked at his regular gigs, at the Auberge and the Chat Noir, where the singers have learned to give him their music ahead of time. He’s never too drunk to play. Perhaps because he’s often operating at the edge of his own confidence, he’s patient, quick to adjust his volume to a nervous voice or circle back for a missed entrance. If an audience member gets too nasty, Erik will shame him from the stage. He writes original songs and lets performers sing them for free. At first the songs were too odd and soft for anyone to bother. But they’ve been getting brassier, sassier. Most remarkably, Erik has never tried to sleep with any of the performers. Yet he knows Bruant would be unimpressed by this list of achievements.

Once the seats are full and the first round of drinks served, Bruant takes the stage and nods his head at Erik. Erik’s fingers, positioned on the keys for the opening of “Le Mirliton,” tremble slightly. The expectant silence is nearly complete. The only sounds are the rustlings of clothing, a few scattered coughs, glasses being set gently on the table.

Erik clatters in with the opening chords and Bruant, full of glorious contempt, screws up repeatedly so that he can blame Erik. The audience batters him with laughter. During the roll call of classics, Bruant throws in some extra names: Massenet and Liszt and Bach. It’s Erik’s one chance in the show to look competent, and he milks it for all it’s worth. Louise has the musical skill to appreciate what he’s doing, and he imagines he’s playing his medley of classics for her.

He can tell Bruant is about to move on to the next bit, and Erik can’t let this chance at the Mirliton go by: he yells out his own name. What he plays is the wrong song for the room, for the mood, the moment, but whatever he plays will enrage Bruant, and this is his favorite of his compositions. It’s three years old and still his favorite, which sometimes frustrates him—why hasn’t he surpassed himself by now?

hope Bruant will pretend to be in on the plan long enough to let him finish.

For the moment the notes drop into a pool of silence, one by one, ripples spreading outward. Both the melody and the quiet, mournful accompaniment of the left hand are delicate. It’s a simple piece; unlike so much else of what Erik has been attempting, there is no sense of the reach exceeding his grasp. The piece is small and complete unto itself, a clear glass globe. It feels like that rarest of rare things, a creation that has come out exactly the way its creator wanted. It’s a song you could weep to, deliciously, but also one so gentle and pretty that you could stop listening to it and just let it hang, draped against the background of your life.

He’s written three of these pieces, all similarly simple, similarly lovely, similarly unheard.

The piece is serene, unashamedly pretty. The crowd is unsure how to react. If it were a cabaret song they would get the joke, but there is no hint of insincerity or showmanship. Bruant stands with his eyebrows nearly disappearing into his hair. Erik is prepared to be stopped at any moment but tries not to rush. If he doesn’t make it to the end, then let whatever fragment the audience hears sound the way it’s supposed to sound. He dares to

There wasn’t really a market for them right now, Eugénie told him matterof-factly when he played them for her and Alfred in the apartment. The name was baffling, Alfred added. It sounded a bit ridiculous—“Gymnopédies”—like made-up Greek. The intent was to evoke ancient statuary, Erik said, the quiet halfsmile of a caryatid. He felt he’d done it, carved three elegant marble statues out of piano notes, but no one else seems to hear them the way he wishes they would.

All Bruant says when Erik finishes is, “Pretty.” Then he’s silent so long Erik wonders if he should push his luck and start playing the second one. He’s trying to feel the room, decipher what they thought. Did they even understand the

piece is his?

“Pretty, like a girl,” Bruant finally adds. “A little sylph.”

Perhaps “sylph” isn’t a bad descriptor? All Philippe said when he first heard it was “Nice.” And Philippe doesn’t know anything about music anyway. He always says Erik’s music is good, even when Erik knows it’s shit.

“Do you have a little sylph, Monsieur Erik? A sweetheart?”

Erik shakes his head.

“Do you have a sister?”

He pauses, but nods.

“Is she pretty?”

He nods again—dangerous, but of course there’s no other option.

“Then let’s have a song about another pretty girl. A little more fun, eh? Since these people have come out for fun.” Bruant flips through the folder on top of the piano, pulls out a song called “Aimée” and hands it to Erik. “What’s her name, your sister?”

This whole turn is so unexpected that Erik wonders if Bruant knows his sister is in the audience. Is this some elaborate plot? He’s afraid to lie. “Louise,” he says.

He’s soon accompanying a song about Lou-Lou-Louise, instead of Ai-Ai-Aimée, a cancan dancer who raises her legs just a bit higher than all the others and wears just a bit less underneath. But oh that bit, that little bit, it makes a big, big difference. With every Lou-Lou-Louise, Bruant grabs his crotch. At first Erik doesn’t notice the gesture—Bruant’s pushing the tempo faster than Erik’s ever played it. Then the audience’s laughter goes up a notch, but Erik knows there aren’t any great lines in the third verse. He finally looks up, straight into Bruant’s face. The man is nearly draped on the piano, rubbing against it. He puckers his lips obscenely around Louise’s name.

Erik keeps playing. Don’t try to leave, he thinks toward Louise, remembering the girls from the first show. This could all get worse. He thinks it toward her the same way he used to push his thoughts toward the mermaid. Maybe it’s working, because Louise stays seated.

But he has forgotten about Pierre. He stands and reaches for Louise’s arm, and Erik can’t tell what’s happening, whether she wants to go or stay. Then Pierre starts to push his way out of the room, leading her by the elbow.

“You forgot your stick,” Bruant shouts, which is true, a fashionable walking stick still hanging on the back of Pierre’s chair. “Presumably it goes up your ass?” But this is too easy—so easy that Bruant’s already losing interest as Conrad grabs the stick and holds it out to Pierre over the heads at the next table. “Why this one?” Bruant calls out. After all, there were racier songs earlier in the evening. Pierre doesn’t bother to answer and Bruant just shrugs, then turns back to Erik, who remains the most rewarding prey on offer.

The rest of the set is a blur. “Good night!” Bruant finally yells. “Show’s over! Don’t come again!” The old hanging chair from the Chat Noir, a parting gift from Salis when Bruant struck out on his own, spins slightly in its wires as the crowd rises to leave.

Bruant picks through the final take

from the hat, counts out Erik’s wage. Instead of reaching for it, Erik sulks. “You already paid me.”

“No, I insulted you. Here’s what we agreed on. The rest is extra. Fun show, in the end. I don’t ever want to see your face again, but I had some fun.”

Reluctantly, Erik takes the money.

“What was that piece you played?” Bruant asks. “The slow one.”

“A gymnopédie,” Erik says, not without a little solemnity, as though trying to slip back into his dignity like it was a jacket he removed at the beginning of the evening. “What did you think of it?” he ventures, even as he’s unsure he truly wants to know.

“I think you brought the room down so far I had to haul it back up with both hands. Melancholy is a dangerous mood. People like a wallow, but they don’t open their pockets for it.”

“Is money your only measure?”

“It’s the most useful one I’ve found. What are you, really? You’re barely an accompanist.”

“I’m a composer.”

Bruant looks at him for a long moment.

“I got pieces of music in the hat once. Little fiddly bits of paper, all rolled up. Initialed E.S. Was that you?”

Erik swallows, tries to discern which answer is the least bad. “Yes,” he admits.

“I tried to play it, out of curiosity. I couldn’t even figure out what order the lines went in.”

“It was just a joke.”

“Was it?”

Erik says nothing.

“I don’t know if you’ve got a hundredthousand-franc piece in you, but those scraps of paper weren’t it.”

“I know,” Erik says, truthfully.

“Good luck with your wallow,” Bruant says.

SUPPORTED BY AFMM, THE MUSÉE’S STEINLEN EXHIBIT RUNS FROM OCTOBER 2023 UNTIL FEBRUARY 11, 2024.

Right beyond the musée’s walls lies the last operational vineyard in central Paris. Established by the City in 1933 to prevent real estate developers from purchasing the land, le Clos Montmartre continues a winemaking tradition that dates back to 944. The vines produce about 1000 bottles a year, and the grapes are actually stored in the basement of the local city hall - only in Montmartre!

forallagesstory

In June 2014, I treated myself to one last stroll around the charming Montmartre neighborhood where we’d stayed the past three nights on our family holiday. The skies were gray and drizzly, but I was prepared – just the day before, I’d purchased a souvenir umbrella decorated with regal black cats. These cats were everywhere in Paris!

Peering into the cluttered window of what I assumed was a thrift shop, I spotted yet another cat – this one a little sculpture made of bronze, not much larger than my hand. Something about the cat spoke to me. I made my way to the front entrance, rang the bell, and waited patiently as the shopkeeper came down the back staircase to open the front door. He spoke only French – and I only understand “un peu de française” – but with some gesturing and “s’il vous plait,” he retrieved the cat from the window to show me.

He pointed to a signature on the bronze. He pointed to my umbrella.

“Oui, les chats,” I nodded, smiling, not yet putting the clues together. He told me the price of the cat - and it dawned on me that this was not a thrift store. These were antiques. Valuable antiques. The bronze was by an artist whose name I had just learned the day before at an exhibit at Musée de Montmartre. Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen.

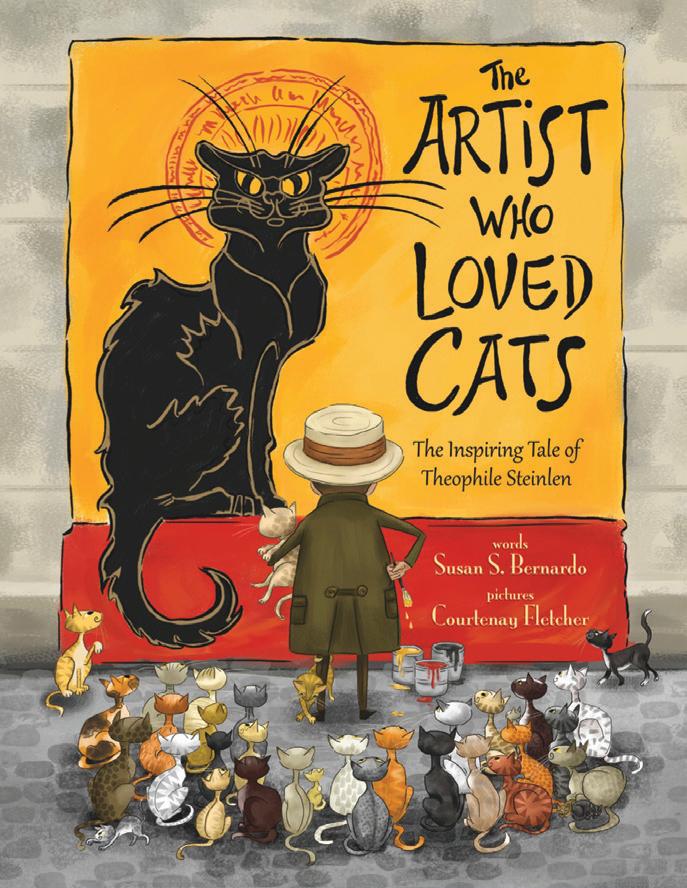

Author and AFMM member, SUSAN SCHAEFER BERNARDO shares shares the inspiration for her picture book biography of Steinlen, The Artist Who Loved Cats.

I wasn’t able to purchase the cat sculpture right then and there (that’s an adventure for another day, involving a midnight ferry, a bus ride back to Paris, and a rendezvous at dawn on Bastille Day!), but as we sat on our train somewhere under the English Channel, an idea for a children’s book leapt into my head. I began jotting down notes and rough verses in my notebook.

Our book opens when a little girl named Antoinette spots a cat in an antique store window – and the

shopkeeper Monsieur Arvieux and his cat tell her about the artist’s life. We named the cat Noir, after the “Le Chat Noir Cabaret” that Steinlen made so famous with his iconic poster.

Once back in California, I shared the idea with my illustrating partner Courtenay Fletcher. She loves Paris and cats and art as much as I do, but this project had to wait. We had others already in the pipeline, and we were just about to launch The Rhino Who Swallowed a Storm, a picture book collaboration with LeVar Burton to help families coping with trauma (that book was read aloud by First Lady Michelle Obama, and sent on a rocket to the International Space Station…but I digress!).

All the while, The Artist Who Loved Cats kept purring along in our imaginations. We began to dive into the research process and the challenge of creating a biography that would capture Steinlen’s many accomplishments and engage children’s imagination. I wanted the book to evoke the same sense of wonder and magic that I felt when I discovered the cat and became curious to learn more about its creation.

While I wrote the text, Courtenay searched for images to inspire her illustrations. In addition to Steinlen’s art, Courtenay found marvelous old black-and-white photos of Montmartre street scenes that informed settings in the book (lucky for us, a new invention called a “camera” became popular in Paris in

1881, around the time Steinlen moved there!). Courtenay also experimented with a charming new illustration style.

Once the book was created, we launched our fourth successful crowdfunding campaign and published the book in 2019. We debuted on stage at the Santa Barbara French Festival on Bastille Day, exactly five years after I first held that magically inspiring cat in my hand! We’ve met so many wonderful people during the process of writing and sharing this book with the world. We first went international in 2021, when a German edition was released by Morisken Verlag.

As the 100th anniversary of Monsieur Steinlen's death (December 13, 1923) approaches, numerous special events will be held to commemorate him and his many artistic achievements! Musée de Montmartre in Paris is hosting a new Steinlen exhibit October 13 through February 2024. On October 11th, I read The Artist Who Loved Cats to school children and AFMM members at the Musée de Montmartre!

In Fine Editions d’Art will also release a French edition of our book. We are so grateful to the wonderful museum staff and to Jacqui Michel and Tim Hanford at AFMM for their warm welcome. It is truly fantastique to be returning to Montmartre nine years after finding my cat to present our book in honor of Steinlen (and, of course, in honor of cats everywhere).

Vive les chats!

The Musée is the lens through which we gain access to the true Montmartre. Join the American Friends as we step back into the Chat Noir, stumbling out arm in arm with our fellow artists, just as they did at the turn of the century.

Take your first step towards Number 12 today at americanfriendsmm.com

ADVISORY BOARD

Jacqui Michel– President

Patricia Nebenzahl – Vice President

Phillip Dennis Cate

Timothy Hanford

Adrienne & Dennis Hensley

Dominique Zuercher

BENEFACTORS ($4K+)

Timothy Hanford

Jacqui Michel & David E. Weisman

PATRONS ($1K+)

Lise Adkins and Tom Murphy

Susan & Charile Bernardo

Adrienne & Dennis Hensley

Cinnamin Malone

Maureen Macfadden

Jocelyn Nebenzahl

Patricia Nebenzahl

Barbara Smith

Jonathan Weisman

Dominique & Gary Zuercher

SPONSORS ($500+)

Jeff Atlas

Kristin Pittman

Vicki and Robert Weisman

EDITORIAL

Jacqui Michel - Publisher

Sophie Evans - Editor in Chief

Tim Kling - Art Director

Norma Thibault – Manager of the Weisman & Michel Collection

AMERICAN FRIENDS OF MUSÉE de MONTMARTRE americanfriendsmm.com

info@americanfriendsmm.com

MUSÉE DE MONTMARTRE Museedemontmartre.fr