by

i. Human Existence Without Architecture – Professional article

ii. The Sheer Pretentiousness Of The Modernist Movement –Research article

iii. Four Steps Towards A Healthier City – Academic article

Professional article Tag(s):

by

i. Human Existence Without Architecture – Professional article

ii. The Sheer Pretentiousness Of The Modernist Movement –Research article

iii. Four Steps Towards A Healthier City – Academic article

Professional article Tag(s):

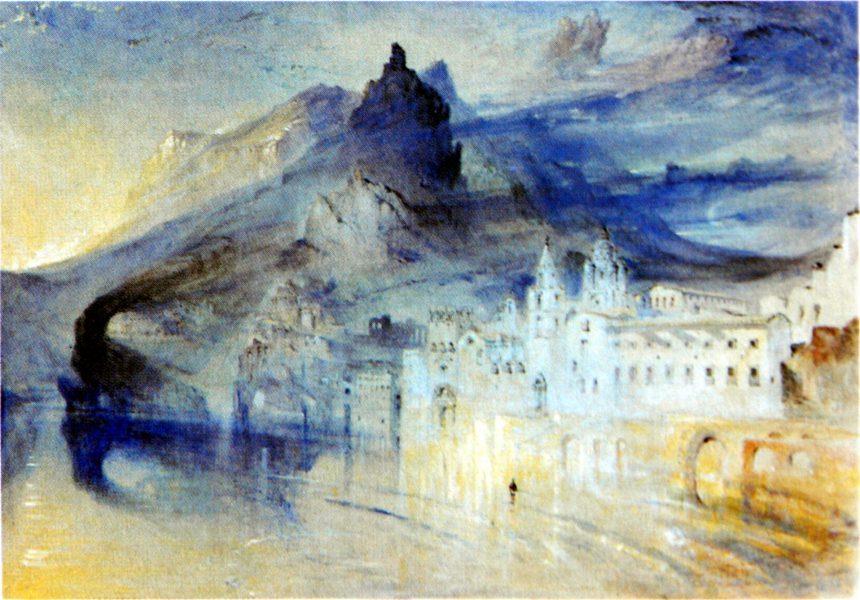

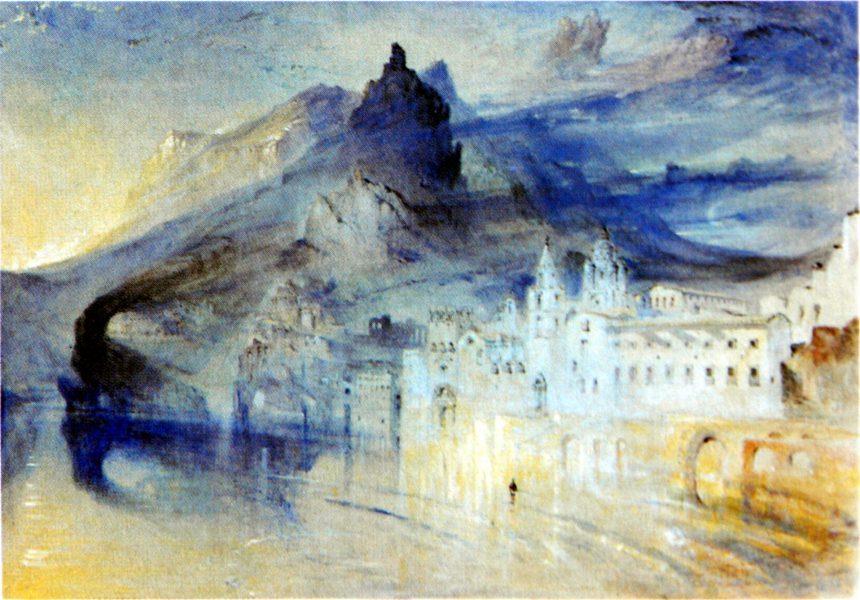

is painting for us, day after day, pictures

of infinite beauty ’ A sensible description of our planet by renowned watercolourist John Ruskin that would stick with us today had human intervention wreaked a lesser impact Evolution, however, is theorised to be inevitable So the emergence of culture and its byproducts are inherent in history, suggesting an increase in human activity and, thus, an impact on the environment. Humans are intelligent creatures, and beyond changes in the environment, we are also conditioned to react accordingly in dire situations, seeking shelter for survival in cases of natural hazards or conflict, a basic need that regulates the limits of our physical bodies and psyche It could be argued that architecture is inevitable, so how would human existence evolve in an architecture-less world? Would cave-dwelling and the hunter-gatherer lifestyle pertain? Would global warming have existed?

Having established seeking shelter as a basic human need, the history of architecture is about as long as the history of humanity as one might expect, and the origins of the discipline can be traced back to the Neolithic period, about 10,000 BC when humans stopped living in caves (BGW Architects, n d) Though an exact date does not exist, remnants of prehistoric structures and ancient civilisations like Stonehenge or Machu Picchu are tools of time determination.

Despite the lack of evidence as to when architecture became common practice before recorded history, one recognises elements of “design” in such built forms when examined in-depth, borne of locality in terms of culture and environment, an observation that has proven architecture is what defines us This is particularly true in the case of vernacular architecture, whose buildings or structures’ design aligns with a specific region or period, is constructed using local materials and resources and is typically realised without the supervision of a professional architect (Thomann, 2023). The true question then becomes, what is architecture?

On a surface level, architecture is commonly known as the process of planning, designing and constructing buildings or structures, perhaps the most universally understood preconception of the discipline. The truth, however, is that architecture stretches beyond the built environment, it’s a part of our culture and stands as a representation of our societal values, a phenomenon tailored for people, by people. Without ideas from the human mind, visions of today's modern world could not exist. Such thoughts are only conceived due to a pure passion for designing

The Tata Somba: Vernacular Exemplar

Take the Tata Somba house of Togo and Benin, for example, a typical dwelling of the Batammariba tribe, an agricultural society whose religious lifestyle plays a key role in everyday life and being at one with their land, an important belief that makes up their identity.

Surrounded by farmland, families typically live in compounds with a series of interconnected tata sambas situated far away from each other to increase the village’s spatial distribution This feature, in the past, would aggravate slave traders due to the inconvenience it caused to their activity (Alatalo, 2020) Additionally, the tata sambas would only have a single entrance, a defensive feature to provide protection from attacks by slave traders and neighbouring tribes.

Standing two storeys high, the ground floor is primarily used as a stable and features a small entrance to create difficulty in maneuvering in the case of an enemy invasion Conversely, the upper floor is where the kitchen and access to the roof are located The roof is where one discovers the bedroom, accessed through a crawlspace opening and simultaneously serves as a granary, which effectively meant that families can remain in their tata sombas for extended periods of time during attacks. As with other traditional houses in the region, tata sombas are constructed using local materials, with their walls composed of earth, straw and cow dung composite Intentionally made thick, they provide excellent insulation against the hot climate while small openings protect against the dusty seasonal harmattan wind To top it off, a special finish, drawn from the contents of the néré fruit, is applied to create a waterproof layer, a common feature also found in the dwellings of the Kassena people of Burkina Faso.

In addition to the cleverly thought-out design features, tata sambas also convey religious significance The dwelling itself represents the spiritual unity of gods, humans and ancestors, with the roof symbolising the sky, the upper floor, the earth, and the ground, the underworld . Much like humans, the Batammariba acknowledge that houses are not built to last an eternity. Most fascinatingly, they are almost treated like humans, some with scars on their facades that resemble those found on the very faces of some of them, the tribe’s members They die with their owner, making the very land they are built on, sacred As such, the next generation builds new houses using old foundations.

Long have humans evolved since the mere need for shelter in the name of survival, and the architecture we see today is very much evident . Primarily assessed through visual means and constantly subject to scrutiny, the emergence of modern architecture has, over time, shown that defining it is a rather complex affair Rejecting historical precedents and traditional construction techniques, modern architecture shows a preference for simple yet visually expressive forms, and it was through the modernist movement that the appreciation of architecture was completely redefined to gravitate towards minimalist approaches. This is where the phrase, ‘less is more’ stems from. Despite being the polar opposite of vernacularism, early 20th century pioneers had demonstrated a fondness for nature, environmentally -centred design and material integrity, characteristics commonly found across the vernacular Frank Lloyd-Wright proposed the idea of “organic architecture” in 1908, stating that buildings should be extensions of the environment, Fallingwater being the very manifestation of his design ethos.

If the aforementioned information proved anything, envisioning human existence in an architecture -less world is a nigh-on impossible task Without architecture, there would be nowhere to display the finest artworks, nothing to house libraries and the countless volumes of documented ideas that shape mankind, and no structures to worship a higher power. What was considered modern at the time will remain modern, totally negating any concept of primitivity and leaving humanity at an impasse.

Research article

Tag(s): Vernacular

architecture showcases clearcut examples of sustainable solutions to building issues, yet such solutions despite their practicality, are assumed to be inapplicable to modern buildings. Despite some views to the contrary, there is a prolonged tendency to associate innovative technology, as the hallmark of modern architecture, for the sole reason that tradition, is perceived to be the opposite of modernity In this article, I critique characteristics of modernist design solutions, and concepts inherent across the vernacular, particularly that of the traditional Malay home

Technology and sustainability constantly prove to be the backbone of the evolving field of contemporary architecture, and architects and designers alike have the challenging duty of designing buildings that align with today’s environmental concerns, yet it is only recently that we realize how powerful the solutions of the vernacular from tropical climates are, low -key solutions that are ignored in contemporary developments As such, this responsibility has conceived a rather utilitarian shift from a biased preference for striking forms to more modest and environmentally aware vernacular designs . Additionally, local construction techniques capitalize on the users’ knowledge of how buildings can be effectively designed while promoting traditional and cultural wisdom (Oliver, 2003).

Several practitioners draw influence from tradition, given that vernacular forms have proven to be energy -efficient and “green”, honed by local resources, geography, and climate (Fathy, 1986; Curtis, 1996) In the topic of vernacular architecture, obscurities arise from the definitions of certain terms or concepts The words “modern” and “traditional” are thought to be in opposition to each other, one may assume that vernacular architecture is a traditional type of architecture, far from the reaches of modern .

In this dualist view, the traditional is assumed to be technologically inferior (Bourdier and Trinh, 1996) This view not only establishes the vernacular as a separate category but at the same time, as stated in his influential book, Architecture Without Architects, insinuates that it is static and unimprovable since it serves its purpose to perfection (Rudofsky, 1964). However, a small number of works on Asian vernacular dwellings, suggest otherwise, fine details, materiality, along with space saving solutions and techniques are utilized resourcefully by the master builders.

The concept of modernism is a rather difficult task of defining, despite rejecting historical precedents and traditional construction techniques. Despite showing a preference for industrial materials and forms of production, modern architecture antithesizes this rhetoric by showcasing simple, yet visually expressive forms and effective functionality, in that there is a rational basis to the building volumes Modernism redefined the aesthetic appreciation of buildings to highlight the phrase ‘less is more’, a phrase used to express the idea that a minimalist approach to artistic or aesthetic features is more effective Ironically, however, the early 20th century pioneers of the movement had demonstrated a fondness for nature, environmental factors, structural precision and material integrity, a myriad of features inherent across the vernacular. Wright had, in fact, discussed the concept of “organic architecture” in 1908, and pushed the idea that buildings should be extensions of the environment, and that their three -dimensional forms should depend upon the properties of materials (Wines and Jodidio, 2000) Masters of modernism, including Corbusier and Aalto, aimed to construct spiritually uplifting environments in which man could live in harmony with nature. While Aalto, believed that the natural energy of light should filter into spaces, and thus, developed a range of techniques to allow for the penetration of natural light into interior spaces, Corbusier was well established for his undying concern with sun, space and green throughout his designs

Vernacular architecture has a rather under-refined concept On a surface level, it can be defined as a type of local or regional construction that uses materials that are sourced locally, where the building is located, and is subsequently related to its context and aware of specific geographic features, and even cultural aspects of its surroundings playing a role in the design. For these reasons, vernacular architecture is unique to different areas of the world, cementing itself as a means of reaffirming identity Possessing unique features, the definition of vernacular architecture may be somewhat unclear, driven by this dilemma, Oliver (2006) professes a desire for a more refined definition for the term. His research has led to the definition of vernacular architecture, as architecture that encompasses the peoples’ dwellings and other constructions, relating to their respective environments and resources, usually built by the owners or the community using traditional techniques It is built to meet specific needs, and accommodate the values, economy, and lifestyles of a specific culture Following this definition, Teixeira (2017), identifies two features of significance in vernacular architecture, tradition and context. He states that all vernacular architecture is traditional, in the sense that it derives from certain ethnic groups and is the product of a long process, based on familiar forms established by previous generations.

Though the modernist movement had the potential to progress in a positive direction, it has instead degenerated into a mere style Our unpleasant modern cities, with their pollution and stress, are a kind of disease that not only refects global environmental sickness but at the same time a wider crisis in the human condition (Richards and Plessis, 2001). Additionally, the haphazard worship of technology and the naive belief that technology could ofer anything to an architect, was one of the major reasons that led to the failure of the modernist movement

The movement believed that the exploitation of technology would not only result in a quicker and cheaper method of construction, but also of a higher standard. Certain techniques and materials proved to be a danger to human health for instance asbestos, cavity insulation, paints, air-conditioning and more. CFC’s (chlorofluorocarbons) were originally thought to be non -toxic, however, it was only after damaging large areas of the ozone that was it realized to be a danger in integrating them into air-conditioning equipment (Papanek, 1995)

Additionally, the very technology deemed to improve lives yields excessive amounts of waste products Energy depleting environments, buildings erected from the exploitation of scarce resources such as timber, sand and steel, using methods that pollute and emit harmful greenhouse gases are performing an assault on the health and livelihoods of people. The construction industry accounts for approximately 25% of virgin wood and 40% of raw stone, gravel and sand every year On a global scale, buildings consume roughly 16% of the water and 40% of the energy used annually, including up to 70% of the sulphur oxides produced by fuel combustion, produced through the generation of electricity used to power households and offices (Dimson, 1996).

To add to this, urban road pollution has established itself as the biggest killer in Malaysia, where I’m originally from, accounting for more than 4,220 deaths a year from lung cancer, bronchitis and coronary heart diseases Fossil fuels and climate instability, two areas of stress, are both influenced by the decisions made by architects, and the survival of mankind and natural systems depend on them (Richards and Plessis, 2001)

Beyond the design and technological aspects, it is also apparent that modern architecture does not align itself with the local culture Form, appearance, size and location are conceived, not merely from physical aspects such as material choice, technology or climate, but rather from society’s ideas, its forms of economic and social organization, and the beliefs and values it upholds at any point (King, 1980) The built environment possesses both subtle and profound influence on the psychological nature of individuals and entire communities What with the rapid rate of urbanization occurring across the globe, and the implementation of standardized techniques, traditional communities were dismantled as a result, and pushed into modern cities filled with high-rise buildings, leading to a loss of interdependence and a sense of identity. Such is the case with many Malaysian cities that favour a more modern outlook in their homogenous nature and diversion from identity.

In what was his career-defining moment, renowned architectural theorist and historian, Charles Jencks, declared July 15th, 1972, the death of modern architecture, firmly established by the first sentence in his 1977 classic, Language of PostModern Architecture, ‘Modern Architecture died in St Louis, Missouri on July 15, 1972, at 3.32pm or thereabouts when the infamous Pruitt-Igoe scheme, or rather several of its slab blocks, were given the final coup de grace by dynamite.' (Jencks, 1977).

Pruitt-Igoe, by Minoru Yamasaki

Built during the height of modernism, Pruitt-Igoe (below), designed by Minoru Yamasaki, was intended to be an affordable, public housing scheme for St. Louis’s rapidly increasing lowincome population . Comprising of 33 cost-effective, eleven -storey high-rise blocks, designed according to the modernist principles pioneered by Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse, an unrealized yet controversial project, Pruitt-Igoe featured the separation of vehicles and pedestrians, through large, slab-like buildings and heaps of green space, resulting in a rather radical, harsh and somewhat totalitarian in its symmetry and standardization

A combination of political and economic factors contributed to the decline of the development, Pruitt-Igoe’s decline began almost immediately, though the federal government provided the funds to construct the development, its maintenance was mainly supported through the tenants’ rent. With the apartments almost exclusively occupied by low -income residents, there were insufficient funds to maintain the 33 blocks which subsequently led to despair Just four years after its opening in 1958, deterioration was already evident, with elevator breakdowns and vandalism being quoted as major problems Furthermore, ventilation was poor due to a lack of centralized airconditioning even during St Louis’s hot summers, stairwells and corridors were a magnet for muggers, a problem exacerbated by the skip-stop elevators and Pruitt-Igoe’s location was not ideal, residing in a “sea of decaying and abandoned buildings” with limited access to commerce, as ground floor businesses were eliminated to save money (Ramroth, 2007)

Academic article

Tag(s): Health & Wellbeing

Thefrst lecture, presented by Tim Townshend,

provided us with an in depth look into the feld of urban design. Firstly delving into key texts and theories within the UK / Western context and understanding the diferent dimensions of the feld, one of which included the link between health and urban design It is far too simple to reduce the complex issue of health and wellbeing to mere articles that remind people of what to do and what not to do, when cities could be designed in such a way to help people actively choose wisely

According to the “Urban design for health: inspiration for the use of urban design to promote physical activity and healthy diets in the WHO European Region” report, urban design has a direct correlation with health “by limiting or providing access to healthy foods and active lifestyles, which have profound efects on people ’s physical and mental health ” (Santos, 2022)

This phenomena was discovered from new research from the US, demonstrating that disease is inevitable These can come in the form of healthrelated diseases but also lifestyle choices, a prime example being the excessive use of the automobile, which through the expulsion of their exhaust fumes can directly lead to health complications. As such, urban planners and architects alike devise ways to overcome these problems, for instance Gehl who emphasizes movement through a pedestrian and cycle-centric city Health and urban planning have been interlinked since the early ages, namely in Ancient Greece, where a sanctuary in Epidaurus was put in place

The image to the right depicts what appears to be an amphitheatre when it is in fact a place of healing where people could receive blessings from the Gods. Should you have fallen sick, the God would visit you in your dreams, after which you ’d report to the priest, who would prepare a cure for you based on the dream. During the recovery process one could attend a theatrical performance in a location that was deliberately picked for its scenic elements, deep in the lush valleys with views of the sea, away from civilization (Brierley, n d )

As Cork is an automobile-oriented city lacking in green space, air quality was inevitably a problem, additionally, outdoor spaces for physical activity were limited . The solution therefore was to integrate public benches with greenery into the urban fabric, promoting opportunities for public interaction (Mythen-Lynch, 2019).

Located in Islington, London, the Grenville Gardens

Allotment project was student-led, aiming to empower and reconnect the community to reclaim its local park Consisting of 18 wooden planting boxes, each constructed and stewarded by a local family. As part of the assembly process each family were presented a step -by-step guide to constructing their allotment box tailored to individual needs through varied heights . The result truly reflected the diversity and eclecticism of the Islington community and its residents (Wood, 2012)

Addressing the impermeability of the urban landscape, rain gardens are put in place to reduce the fow rate, quantity and pollutant load of stormwater runof . This method is primarily used to treat urban runof through the use of plants, stones or other natural elements In 2019, however, the frst rain garden in Rio was installed at the Fundiçao Progresso Cultural Centre where a concrete sidewalk in front of the building was removed in favour of 200sqm of green space and eventually became a community based activity (Ghisleni, 2022).

Beginning in 2015 after a multimillion dollar investment into the project, the project, which concluded in July 2021 included new widened stone and concrete sidewalks, urban furniture comprising of benches and bike racks, new drainage system, parking and more This work stretched from N Halsted Street all the way to N Ogden Avenue to the west and is designed to preserve the area’s historic character (Achong , 2022)