VOL. 80 PART 6 THE NOVEMBER 2022

ADVOCATE

Vancouver • New Westminster • Victoria Tel: 604-659-8600 • Toll Free: 800-553-1936 • info@wcts.com • wcts.com Don’t let important matters “fall” through the cracks... • Court Registry Services • Process Serving & Skip Tracing • Land Title Registry Services • Corporate Registry Services Our attention to detail is your safety net • Personal Property Registry Services • Manufactured Home Registry Services • Vital Statistics Registry Services • Government Registry Searches of all types Proudly serving the legal profession since 1969

THE ADVOCATE 801VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022 FromOurFamilytoYours appy Holidays WWW.DAVIDSON-CO.C H OM

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022802 THE ADVOCATE (csconomiPhD E rotiationssuppoNeg+ c Cpecifis S’& Canada ed as an experQualifi DRED + T UBC, 1982) rt:valuesofoffers bunalrilaims T Courtupreme BLEWET t in BC S onsExpert Opini+ aluationsmiEcono c V+ tiocConsulStrategi ta+ f de oluc vamiEcono+ onsforcomPIDopini+ teroffersand coun ns amages mmercialfishers 60449997615 ed ww 4.999.7615 win@gocounterpoint.com w.gocounterpoint.com ustTr eagHerit W We e help clients protect t .caustcompanrgetwww.herita y heir families, their assets and their leg acies. 3W 1N6, BC Vy,rd., Sur200 – 7404 King George Blv C57T 1, BC VerVaancouvWeAvveny220 – 545 Cl de A ue, West V ey ustcompany..cagetrnicole@herita 778.742.5005 y nty yy pp,g Regulated b the British Columbia Financial Services Authorit (BCFSA), Heritage Trust provides caring and professional executor, trustee and power of attorne ser vices for BC reside t clients. Nicole Garton, B.A., LL.B, LL.M., C.Med, FEA, TEP President, Heritage Trust

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022THE ADVOCATE 803 Dispute Resolution Servic 27 years as a leading litigator, ha• criminal, civil and family claims s appeared Presided over all manner of case• s including Appeal, 12 years as a Supreme Court Judge. 21-year judicial career: 9 years o ces Mediation, Arbitration & n the BC Court of• on commercial and insurance dissputes. of dispute resolution with an emphasis arbitration, mediation, and other forms Immediately available to assist w with Effective and respected decision• Supreme Court of Canada -maker in all courts of British Columbia and the ygg rgoepel@watsongoepelc6046425651| com Richard Goepel, K.C. MOVE FORWARD WITH CONFIDENCE rgoepel@watsongoepel c604.642.5651 | .comwatsongoepel

OFFICERS AND EXECUTIVES

LAW SOCIETY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA

Lisa Hamilton, K.C. President

Christopher McPherson, K.C.

First Vice President

Jeevyn Dhaliwal, K.C. Second Vice President

Don Avison, K.C. Chief Executive Officer and Executive Director

BENCHERS

APPOINTED BENCHERS

Paul A.H. Barnett

Sasha Hobbs Dr. Jan Lindsay

ELECTED BENCHERS

Kim Carter

Tanya Chamberlain

Jennifer Chow, K.C.

Cheryl S. D’Sa

Lisa H. Dumbrell

Brian Dybwad Brook Greenberg, K.C.

Katrina Harry Lindsay R. LeBlanc Geoffrey McDonald Steven McKoen, K.C.

Michèle Ross Natasha Tony Guangbin Yan

Jacqueline McQueen, K.C.

Paul Pearson Georges Rivard Kelly Harvey Russ Gurminder Sandhu Thomas L. Spraggs Barbara Stanley, K.C. Michael F. Welsh, K.C. Kevin B. Westell Sarah Westwood Gaynor C. Yeung

ABBOTSFORD & DISTRICT

Kirsten Tonge, President

CAMPBELL RIVER Ryan A. Krasman, President

CHILLIWACK & DISTRICT Nicholas Cooper, President

COMOX VALLEY Michael McCubbin Shannon Aldinger

COWICHAN VALLEY Jeff Drozdiak, President

FRASER VALLEY Michael Jones, President KAMLOOPS

Kelly Melnyk, President

KELOWNA

Taylor-Marie Young, President KOOTENAY

Dana Romanick, President

NANAIMO CITY

Kristin Rongve, President

NANAIMO COUNTY

Lisa M. Low, President

NEW WESTMINSTER Mylene de Guzman, President

NORTH FRASER Lyle Perry, President

NORTH SHORE Adam Soliman, President

PENTICTON

Ryu Okayama, President

PORT ALBERNI Christina Proteau, President

PRINCE GEORGE Marie Louise Ahrens, President

PRINCE RUPERT Bryan Crampton, President

QUESNEL Karen Surcess, President SALMON ARM Dennis Zachernuk, President

SOUTH CARIBOO COUNTY Angela Amman, President

SURREY Gordon Kabanuk, President VANCOUVER Executive Jason Newton President Niall Rand Vice President

Zachary Rogers Secretary Treasurer Samantha Chang Past President

VERNON Christopher Hart, President

VICTORIA Marlisa H. Martin, President

CANADIAN BAR ASSOCIATION

BRITISH COLUMBIA BRANCH

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Aleem S. Bharmal, K.C. President Scott Morishita First Vice President Lee Nevens Second Vice President Judith Janzen Finance & Audit Committee Chair Dan Melnick Young Lawyers Representative Rupinder Gosal Equality and Diversity Representative Randolph W. Robinson Aboriginal Lawyers Forum Representative Patricia Blair Director at Large Adam Munnings Director at Large Mylene de Guzman Director at Large Sarah Klinger Director at Large

ELECTED MEMBERS OF CBABC PROVINCIAL COUNCIL

CARIBOO

Nathan Bauder Susan Grattan Nicholas Maviglia

KOOTENAY Andrew Bird Christopher Trudeau NANAIMO Johanna Berry Patricia Blair Kevin Simonett

PRINCE RUPERT Sara Hopkins VANCOUVER Kyle Bienvenu Karey Brooks Joseph Cuenca Bahareh Danael Graham Hardy

Lisa Jean Helps Judith Janzen Heather Mathison Scott Morishita

VICTORIA Sarah Klinger Dan Melnick Paul Pearson

WESTMINSTER Anouk Crawford Mylene de Guzman Daniel Moseley Greg Palm

YALE Rachel LaGroix Michael Sinclair Kylie Walman

CANADIAN ASSOCIATION OF BLACK LAWYERS (B.C.)

Zahra Jimale, President FEDERATION OF ASIAN CANADIAN LAWYERS (B.C.) Steven Ngo, President

INDIGENOUS BAR ASSOCIATION (B.C.) Michael McDonald, President

SOUTH ASIAN BAR ASSOCIATION OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Anita Atwal, President ASSOCIATION DES JURISTES D’EXPRESSION FRANÇAISE DE LA COLOMBIE-BRITANNIQUE (AJEFCB)

Sandra Mandanici, President

804 THE ADVOCATEVOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

BRITISH COLUMBIA BAR ASSOCIATIONS

THEADVOCATE

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

Published six times each year by the Vancouver Bar Association

Established 1943 ISSN 0044-6416 GST Registration #R123041899

Annual Subscription Rate $36.75 per year (includes GST)

Out-of-Country Subscription Rate $42 per year (includes GST)

Audited Financial Statements Available to Members

EDITOR: D. Michael Bain, K.C.

ASSISTANT EDITOR: Ludmila B. Herbst, K.C.

EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Anne Giardini, O.C., O.B.C., K.C. Carolyn MacDonald David Roberts, K.C. Peter J. Roberts, K.C. The Honourable Mary Saunders The Honourable Alexander Wolf

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Peter J. Roberts, K.C. The Honourable Jon Sigurdson Lily Zhang

BUSINESS MANAGER: Lynda Roberts

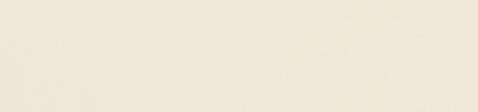

COVER ARTIST: David Goatley

COPY EDITOR: Connor Bildfell

EDITORIAL OFFICE: #1918 – 1030 West Georgia Street Vancouver, B.C. V6E 2Y3

Telephone: 604-696-6120

E-mail: <mbain@the-advocate.ca>

BUSINESS & ADVERTISING OFFICE: 709 – 1489 Marine Drive West Vancouver, B.C. V7T 1B8 Telephone: 604-987-7177

E-mail: <info@the-advocate.ca>

WEBSITE: <www.the-advocate.ca>

Entre Nous . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 809

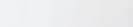

On the Front Cover: Aleem Bharmal, K.C. By Louisa Winn, K.C., and Tina Parbhakar . . . . . . . . . . . 815 Haldane

By Christopher Harvey, Q.C. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 823

Ontario Court of Appeal Denies Preconception Medical Duties to Future Children: Why British Columbia Should Not Follow Ontario’s Lead By Aminollah Sabzevari . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 833

The Canadian Legal Genealogy of Terra Nullius – Sub Nom.: Is It Too Late to Send Terra Nullius Back to Australia (and Would They Even Take It)? Part II By Sarah Pike . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 839

Got Privilege? Things You Didn’t Know You Didn’t Know By David Wotherspoon and Alim Khamis . . . . . . . . . . . . . 851

Conscious of the Good Conscience Trust: Further Thoughts on the Constructive Trust in Wills Variation Claims By Mark Weintraub and Polly Storey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 859

The Wine Column . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 867 News from BC Law Institute . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 873

LAP Notes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 877 A View from the Centre . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 879

Announcing the 2023 Advocate Short Fiction Competition . . . 883 Peter A. Allard School of Law Faculty News . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 885

UVic Law Faculty News . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 889

The Attorney General’s Page . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 893 Nos Disparus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 897 New Judges . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 909 New Master . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 915

Letters to the Editor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 919

Classified . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 923

Legal Anecdotes and Miscellanea . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 925

From Our Back Pages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 931

Bench and Bar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 947

Contributors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 959

ON THE FRONT COVER

Aleem Bharmal, K.C., is the new CBABC president. Read how this kid from Scarborough went from being a Bay Street lawyer to a BBQ’d lasagna eating director of the Community Legal Assistance Society and beyond at p. 815.

“Of interest to the lawyer and in the lawyer’s interest”

Medical Malpractice is all we do

Tel: 604.685.2361

Toll Free: 1.888.333.2361 Email: info@pacificmedicallaw.ca www.pacificmedicallaw.ca

We are a firm ofconsulting economists who specialize in providing litigation support services to legal professionals across western Canada. Our economic reports are supported by knowledgeable staffwith extensive experience in providing expert testimony.

We offer the following services in the area ofloss assessment:

Past and future loss ofemployment income

Past and future loss ofhouseholdservices

Past and future loss offinancial support (wrongful death)

Class action valuations

Future cost ofcare valuations

Loss ofestate claims (Duncan claims in Alberta)

Income tax gross-ups Management fees Pension valuations

Future income loss and future cost of care multipliers

806 THE ADVOCATEVOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

A FOUNDING MEMBER OF BILA

QUANTIFYING ECONOMIC DAMAGES SINCE 1983 DARREN BENNING PRESIDENT info@petaconsultants.com T. 604.681.0776 F. 604.662.7183 Suite 301,1130 West Pender Street Vancouver,B.C.Canada V6E 4A4

PETAConsultants Ltd.

Davis has been entrusted with the investment portfolios of legal professionals in British Columbia and Alberta for 20 years. Attuned to your needs, he understands that the demands of being a successful lawyer often result in a lack of time to manage your own investments.

Odlum Brown, Jeff develops investment strategies that are conflict-free and focused on creating and preserving the wealth and legacy of his clients. For over two decades, the results of the highly regarded Odlum Brown Model Portfolio have been a testament to the quality of our advice.

THE ADVOCATE 807VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022 a l s ·orstoliciSrss&etis iBar· paanyal & ComosG p r r TIONTAEE CONSULFR 604.591.8187 www.wcblawyers.com Wo r kSafeBC Appe B.A., LL.B. salj GoSar 7AStreet,Surrey,BC3916304-93 Centre 2City M1V3T0

Jeff

At

Built on Trust, Backed by Results

Davis, B.Comm, CIM Vice President, Director Portfolio Manager COMPOUND ANNUAL RETURNS (Including reinvested dividends, as of September 15, 2022) 1 YEAR3 YEAR5 YEAR10 YEAR20 YEARINCEPTION1 Odlum Brown Model Portfolio2 2.4%11.0%10.9%12.8%12.2%14.2% S&P/TSX Total Return Index -2.7%8.7%8.4%7.8%8.6%8.4% Let us make a case for adding value to your portfolio; contact Jeff today at 604-844-5404 or jdavis@odlumbrown.com. Visit odlumbrown.com/jdavis for more information. 1 December 15, 1994. 2 The Odlum Brown Model Portfolio is a hypothetical all-equity portfolio that was established by the Odlum Brown Equity Research Department on December 15, 1994 with a hypothetical investment of $250,000. It showcases how we believe individual security recommendations may be used within the context of a client portfolio. The Model also provides a basis with which to measure the quality of our advice and the effectiveness of our disciplined investment strategy. Trades are made using the closing price on the day a change is announced. Performance figures do not include any allowance for fees. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. Member-Canadian Investor Protection Fund

Jeff

808 THE ADVOCATEVOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

ENTRE NOUS

Is law a trade? We’ve heard the “trade” label applied again recently to our line of work. It is somewhat less common than the “law as business” characterization,1 but occasionally used as well (indeed, in some definitions, trade and business are synonymous). We reflect on the “trade” label below.

“Trade” is “the activity of buying and selling, or exchanging, goods and/or services between people or countries”, a “particular business or industry” or a “job, especially one that needs special skill, that involves working with your hands”.2

In all these various guises, there is undoubtedly something solid and reassuring about the word “trade”. Many of its connotations are positive. Goods or services that are traded can be the product of considerable skill; skilled craftspeople are the epitome of those practising a trade. Indeed, for anyone to engage in trade sustainably, the goods or services they trade should be of sufficient quality to attract both repeat and new customers.

A trade is a form of exchange. In return for the goods or services that a person provides, the provider should receive payment—a welcome prospect for many of us in law, though not necessarily always the reality, as returned to below. No one would expect a tradesperson in a conventional sense to keep extending indefinite credit; who would look down upon a tradesperson seeking payment in exchange for the goods or services traded?

At the same time, conventional trades are not necessarily known for exorbitant incomes, so the tradesperson label—no matter the reality—at least would detach us somewhat from an image of offensive wealth.

Being seen to accept, or even embrace, the characterization of our line of work as a “trade” might also do other wonders for our image. It would mean we are not elitists insisting on a highfalutin status and thinking we are better than the skilled craftspeople and business owners more commonly associated with the trading label.

THE ADVOCATE 809VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

Reach as we might, though, and while there are aspects of overlap, the reality is that law is not a trade. And while in some respects the trade characterization is pleasant and even positive for our image, in other respects it is dangerous.

To differentiate between the two is not to say we are better than those engaged in trade—just that we have a different role. And the differences are not necessarily ones that make our lives easier; to the contrary, the differences can make our day-to-day work less certain and more difficult.

At heart, what we offer is the exercise of judgment, including as to whether we should provide more tangible work product, and if so, what it should be and when it should be done.

For the most part, we are not in the business of selling a particular good, though sometimes, and in itself not without difficulty, we can provide some approximation of this with unbundled services. This is much to the disappointment of clients or prospective clients who contact us demanding that we take on a particular task, such as writing a letter to one of their foes. In telling that client or prospective client “Well, sorry, there’s nothing lawrelated to say” or “Strategically, that’s not a good idea” or “Well, that’s actually not lawful”, we are not exactly maximizing our volume of sales. Rather, we may talk the “customer” out of hiring us at all or recommend a nature and volume of work inconsistent with generating a return.

Even where we provide a particular category of good or service repeatedly in our practice, usually it is not an off-the-shelf kind of product in each case. Circumstances tend to call for different wording and approaches in each of our letters, contracts, pleadings and written submissions.

Of course, custom orders are far from unknown in trade. However, unlike the cabinets in a kitchen, it is not the client’s vision of what a given letter should say (or, typically, how strident it should be) that should be driving certain customization—rather, the decisions on the content and appearance of the documents that emanate from our offices at their core should rest on, or at least be consistent with, our own views of what is appropriate, though responsive to overall client interests and goals.

Every time we engage with a client, we need to consider whether—and if so, how—to do what is sought, or whether a different approach will serve the client’s interests, or if we can engage with this particular client at all.

When we do not do this, we put at risk not just the interests of that particular client in the long term, but also our reputations and potentially the public interest as a whole. We should not aspire to be like the “hired guns” who simply do the bidding of a client in court or other contexts.

No doubt a person engaged in trade may also resist or refuse a particular transaction. They may say “no” to crafting a commissioned piece with an

810 THE ADVOCATEVOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

unlawful or otherwise offensive message, or a sale to a villainous customer, or a sale of a particular piece of clothing to someone unsuited to it. However, we expect those should be exceptions to the rule that a good or service is available for purchase.

When a solicitor-client relationship is established, the obligations we have in that relationship are fierce. The duties of loyalty and confidentiality that arise have a ferocity that the purchaser of a handicraft from a seller would find a surprising accompaniment to that act of trading.

Beyond the bilateral relationship that is also found—albeit in much less intense form—in trade, we also have broader and other obligations to courts, other lawyers and the public. Those obligations in turn inform whether we establish the bilateral relationship with a given individual as client, and if so, what that consists of.

An element of our work is public service. The service to the public that we perform does not consist simply—or may not consist at all—of providing the work that a given member of the public would like us to do. That work product may, on balance, either not be of service to that person, or be incompatible with other obligations and contrary to the public interest at large.

It is not that those in trade are immune to external influence on the relationship they have with their customers; those in trade also have obligations to the state, and indeed the quality of their wares and services may be regulated by it. However, as we may be defending clients against the state and seeking to change and improve the laws that the state otherwise imposes, regulation of the bar needs a degree of independence that regulation of a trade does not.

The notion of work being done pro bono is also somewhat at odds with the “trade” label. To trade is to exchange, conventionally a good or service for a monetary benefit, or at least for a good or service bartered in return. This is not to say that a person engaged in a trade may not occasionally donate goods or services, or offer a discount, but it is not expected. Further, the balancing that many of us do when looking at the totals to which our hourly rates have caused pre-bills to skyrocket, to determine a fair and reasonable approach and how much to write off, certainly departs at least from the notion of a standardized price list.

All this reflection and consideration are difficult, even if patterns tend to emerge that may spare us from needing to re-do it from scratch in every case. Sometimes the scenarios repeat themselves enough to have given rise to precise rules for us to apply. Others are strange and new and varied and require considerable reflection to sort through. We never know on any given day which scenario(s) we will face.

THE ADVOCATE 811VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

To do their work well, lawyers need various supports that may not have equivalents in trade. They need education broad enough to teach them to deal with difficult and changing circumstances in which, rather than provide a good or service, or the client’s desired good or service, a lawyer should not or cannot. Their knowledge needs to be refreshed and kept alive. They need practice advisors to assist them and regulatory structures that seek to prevent issues from arising but address them where they do. They need to know there are colleagues around whose experiences they share, and inspiring role models who weathered the same issues during their careers.

Unless equipped to do their work in the manner outlined above, ultimately there will be fewer lawyers able to provide assistance, and those who continue in practice may be less able to do their work well. They need an excellent regulator mindful of issues related to lawyers and their relationships with clients and the state, they need educational resources as well as resources that inspire collegiality and professionalism, and they need the Lawyers Assistance Program.

Whether in funding decisions or in reshaping regulation in this province, care needs to be taken to appreciate that shifting attention to one priority— and sapping the funding and energy otherwise devoted to another—may ultimately damage even the ability to achieve the objective that was favoured.

There are many issues ahead in this province, with which lawyers and others will need to grapple, regarding such matters as regulation, the nature of services to be provided by different providers, and the relative funding for different supports for lawyers in allowing them to serve the public and the public interest. We urge for consideration the matters highlighted above.

ENDNOTES

1. On what to make of the “business” label, and the intersection between business and the profession of law, see for example Ian Binnie, “Boom in the Law Business” (2007) 65 Advocate 39 (which also contains an entertaining account of the former judge’s experiences in practice); Sandra L Kovacs, “Call to

Service: Preserving Our Professionalism in the New Business Model” (2015) 73 Advocate 355; Frank Iacobucci, “The Practice of Law: Business and Professionalism” (1991) 49 Advocate 859.

2. Cambridge Dictionary, sub verbo “trade”, online: <dic tionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/trade>.

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

812 THE ADVOCATE

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022THE ADVOCATE 813

+SPONSORS VOLUNTEE We extend our sincerest grat THANK YOU TO ONORS itude to the 177 volunteer lawyers RS, who served clients at our British Columbians. With you sponsored a volunteer lawye We also extend thanks to our virtually from every corner o they provided free legal advi 15th annual legal advice-a-th TITLE SPONSOR Thanr help, we raised $123,600. r to support our mission to increa event sponsors and to everyone w f the province ce to 333 low-income British Colu on this September. Over the cou nk you! se access to justice for all who donated funds or umbians in person and se of the 10-day event, MEDIA SPONSOR SUPREME COURT SPONSORS A V PPEAL COURT SPONSORS Blakes DLA Piper (Canada) LLP Law Society of BC Surrey Bar Association Viictoria Bar Association SINGTEAMS rs Sutton LLP LLP LLP Association of BC Association TOPFUNDRAISERS TRIAL COURT SPONSORS Abbotsford & District Bar Association Alexander Holburn Beaudin + Lang LLP Carfra Lawton LLP Crossroads Law Dentons Edwards, Kenny & Bray LLP Hamilton Duncan Hammerco Lawyers LLP TOPFUNDRAIS V T Slater V oper G HHBG Lawye JFK Law Richards Buell R reyell L Veecchio Trrial Lawyers A Vaancouver Bar accessprobono.ca/ vTo get involved, visit: AshaY isoo V T amily Law GW TOP FUNDRAISERS Jennifer Flood – ThorsteinssonsLLP Wiilliam Storey – Kitsilano F roup Trroy McLelan – Simpson, Thomas & Associates J Viis – Lawson Lundell LLP Yooung – Lawson Lundell LLP WhitelawT Clark W TOP FUNDRAIS Lawson Lundel Thorsteinssons DLA Piper (Can Wiilson L Twwin olunteer-with-us SING TEAMS l LLP LLP ada) LLP LP ning

DO

Suite 700 – 1177 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, BC, V6E 2K3

Telephone: 604.687.4544 • Facsimile: 604.687.4577 • www.bmmvaluations.com

Vern Blair: 604.697.5276 • Rob Mackay: 604.697.5201 • Gary Mynett: 604.697.5202

Kiu Ghanavizchian: 604.697.5297 • Farida Sukhia: 604.697.5271

Lucas Terpkosh: 604.697.5286 • Sunny Sanghera: 604.697.5294

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022814 THE ADVOCATE

Business Valuations • Matrimonial disputes • Shareholder disputes • Minority oppression actions • Tax and estate planning • Acquisitions and divestitures Personal Injury Claims • Income loss claims • Wrongful death claims Economic Loss Claims • Breach of contract • Loss of opportunity Business Insurance Claims • Business interruption • Construction claims Forensic Accounting • Accounting investigations • Fraud investigations

Litigation Support Group

to Right: Kiu Ghanavizchian, Sunny

The

Left

Sanghera, Gary Mynett, Lucas Terpkosh, Vern Blair, Rob Mackay, Farida Sukhia

ON THE FRONT COVER

ALEEM BHARMAL, K.C.

By Louisa Winn, K.C., and Tina Parbhakar

Aleem Bharmal, K.C., is unassuming in nature and, as many will attest, universally liked. But do not let that fool you. He is a skillful defender of the downtrodden. He is unflappable, methodical, principled—not easily riled, nor easily dissuaded.

Whereas for some “social justice” is construed so narrowly that it conjures up only pickets and megaphones, Aleem’s dedication to this concept is a deep, broad and enduring one. This dedication includes bringing diverse individuals together time and again to develop responses to emerging issues and polite yet persistent advocacy for policy changes until they are made.

There is much talk about “leaders eating last” these days. Well, Aleem has consistently set the stage for a shared meal and stayed behind to tidy up.

In September 2022, Aleem steps into the position of president of the Canadian Bar Association, B.C. Branch (“CBABC”). 1 Countless lawyers, members of the legal sector and judiciary, and friends from the greater community will come together and celebrate the occasion. We will be among them and are thrilled to write about this human rights lawyer and what you can expect from his presidency.

A COMMITMENT TO RESPECTFUL RELATIONS

In 1994, after growing up in Scarborough, Ontario and earning an undergraduate degree in philosophy and actuarial science from the University of Toronto, Aleem graduated from UBC Law and obtained articles at a prestigious law firm with the esteemed Gordon Turriff, Q.C., as his principal. During his articles, when a senior partner at that firm made an obviously racist joke about South Asians, Aleem called out the behaviour without a second

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022THE ADVOCATE 815

thought. The lawyer did not seem to see the problem. Aleem consulted those he trusted and decided to bring the incident to the attention of the Law Society. As far as Aleem could tell, his concern was minimized again. This early experience in law, over 30 years ago, set the tone for Aleem’s career trajectory.

Aleem’s parents, Shiraz and Nurjehan, were brought up in Tanzania as members of a diaspora community from the Gujarat region of India, which had settled in eastern Africa in the early 1900s. In 1971, they migrated to Canada from the United Kingdom, where they had both been studying, due to the growing anti-Asian sentiment in both eastern Africa and western Europe in the 1960s and early 1970s. Thus, his family’s experiences led Aleem to be particularly alive to the dynamics of difference, ignorance and hatred, yet also to the power of people, like his parents, who were adamant about mutual respect and dedicated to mutual assistance. They made supporting family and friends and displaced communities, like their own, an intrinsic part of Aleem and his younger siblings’ early lives.

After completing articles in Vancouver, and despite his parents’ reservations, in early 1996, Aleem took those familial values and headed off to Kigali, to work as a human rights officer for the United Nations’ High Commissioner for Human Rights. His task was to help report on the administration of justice and ongoing human rights violations, less than two years after the 1994 Rwandan genocide. Although he felt compelled to leave by the fall of 1996, given the mounting nearby fatalities from militant crossborder incursions and a government counter-offensive, Aleem returned to Toronto with even more resolve to address human rights issues.

FROM BAY STREET TO GEORGIA STREET

In the late 1990s, articles in Ontario were 18 months long. Aleem had to find “top-up” articles and was fortunate to complete them under the renowned refugee lawyer, Barbara Jackman. Next, he joined a boutique firm at the iconic Toronto Flatiron Building with the multifaceted Jerry Levitan. Aside from writing The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Winning Everyday Legal Hassles in Canada, Jerry’s claim to fame was for having, as a teen, interviewed John Lennon and Yoko Ono just prior to their 1969 “Bed-In for Peace” protest against the Vietnam War.2

In 1998, Aleem headed to Bay Street to practise employment law with Miller Thomson LLP. He became privy to billable-hour and client development pressures associated with big firm practice. On the upside, demand for associates was booming in Toronto, and that meant lots of work, competitive salaries and glorious perks. However, the novelty of fancy recep-

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022816 THE ADVOCATE

tions, platinum tickets to Raptors’ games and kudos for climbing the hierarchy wore off for Aleem. While at a firm event at Casa Loma, an occasion with live performers, colleagues dressed to the nines, flowing fine wine and even a chocolate fountain, Aleem felt a distinct and undisputable yearning to shift back to social justice lawyering.

Fortuitously, Aleem’s friend and former colleague, Mandeep Gill, who is now in the foreign service, suggested he consider approaching the Community Legal Assistance Society (“CLAS”) about an opening. In 2002, the newly elected provincial government disbanded the BC Human Rights Commission as a cost-cutting measure. CLAS was tasked with developing a directaccess human rights clinic to address a huge backlog of cases that the commission, which had functioned as a gatekeeper, left behind. Aleem successfully applied to join this new Vancouver clinic, once again undeterred by those who expressed reservations. Aleem has since devoted his energies to human rights claims in this province, led CLAS for over a dozen years and participated in countless social justice community initiatives.

CLAS SOCIALS, WORKING AT CLAS AND WORKING CLAS SOCIALS

The first CLAS social event that Aleem attended was a casual potluck at the home of Jim Pozer, Q.C. (as he then was), CLAS’s executive director at the time. Jim’s oven had broken down, which meant the frozen lasagna Jim planned to serve had to be cooked in his BBQ. The warmth, laughter and engaging legal conversations Aleem experienced that night confirmed for him that this was his home in the law. Aleem also fostered this CLAS culture as executive director. He enthusiastically supported events such as annual summer BBQs featuring highly anticipated team games including the water balloon toss and three-legged race, Halloween costume competitions with fiercely fought battles between CLAS programs and even karaoke nights, where Aleem belted out corny standards by Journey and The Boss.

Yet Jim did not just inform Aleem’s approach to gathering; he also mentored Aleem in leadership and litigation. As a result, Jim also came to trust Aleem with the role of interim executive director when required. In 2007, after 23 years with CLAS, Jim retired due to health issues. Aleem was chosen to be the executive director, following in the giant footsteps of past executive directors. These included Mike Harcourt, who founded CLAS in 1971 before becoming mayor of Vancouver and ultimately premier; the late Ian Waddell, Q.C., who, after leading CLAS, had an illustrious political career with the provincial and federal NDP; and, of course, Jim, under whose leadership CLAS steadily expanded and was nationally recognized for its role in precedential cases, despite a period of significant cuts to legal aid in the province.

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022THE ADVOCATE 817

Indeed, 2007 was a whirlwind year, with the new executive director responsibilities and the arrival of his second child. That year, Aleem, with Clea Parfitt joining him as his co-counsel, also took on a human rights case brought by over 20 South Asian veterinarians who alleged systemic discrimination by their professional association and regulator.

Menacing hurdles soon arrived with the 2008 world economic downturn and funding cuts in 2012, reminiscent of those Aleem’s predecessor had faced in 2002. The 2012 cuts reduced both salaries and staff. But Aleem steered CLAS through these tough years like “a calm sailor in rough seas,” according to a colleague. Working closely with Rita Hatina, director of administration and finance, Aleem ensured that the CLAS team endured and surmounted financial threats, ultimately emerging from them stronger.

In particular, 2015 saw the BC Human Rights Coalition merge with CLAS, returning staff numbers back to 2007 levels. The next big CLAS expansion occurred toward the end of Aleem’s term as executive director, when CLAS applied for Department of Justice funding and was awarded a multi-million dollar grant for new legal services to address workplace sexual harassment. During this period, CLAS also represented parties or intervened at the Supreme Court of Canada six times and its Mental Health Law Program grew to respond to over ninety per cent of demand for representation in British Columbia.

Aleem remained busy in his legal practice. Notably, the “Indo-Canadian Veterinarians Case” took over five years and 300 days of hearing to conclude. After multiple motions, challenges and even a trip to a higher court to deal with a reasonable apprehension of bias allegation, Aleem and Clea ultimately succeeded in convincing the tribunal about the BC College of Veterinarians’ widespread misconduct, characterized by racial bias and systemic discrimination, resulting in significant individual and systemic remedies for their clients.

As the executive director of CLAS, Aleem maintained a perpetually open door and a well-stocked mini-fridge in the boardroom. He also put on fabulous fundraisers. With Rita’s able assistance, he managed relationships with multiple funders and stakeholders with aplomb. He also continued his highvolume human rights legal practice, ever determined to give voice to those who were being silenced or marginalized. Each dimension of his work at CLAS contributed to his broader advocacy inside and outside of the nonprofit.

Throughout his career, Aleem has remained a devoted father to his two children. He made and continues to make time to mentor law students and junior lawyers and participate in initiatives that impact access to justice. He

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022818 THE ADVOCATE

was part of a team of concerned lawyers who created the Islamophobia Legal Assistance Hotline during a period of rising negative rhetoric and violence against Muslims or those perceived to be Muslim. He also took on the role of running the Social Justice Listserv, with over 575 subscribers from the social justice sector.

By 2019, the results of Aleem’s steady leadership at CLAS ironically set the stage for him to step away from the executive director role. He and his team had managed to expand and improve programs and advocacy, such that the organization reached a staffing level of over 40 and a budget of over $4 million. CLAS now needed a full-time executive director with non-profit management expertise. After a careful search, aided by Aleem and Rita, Jacqui Mendes ably took over the role of executive director, just as the global pandemic set in. To Aleem’s relief, Jacqui handled this challenge with grace and skill. This transition was actually ideal for Aleem, who wished to return to being a full-time lawyer and devote more time to his legal volunteer work, particularly with the CBABC. Before we close with Aleem’s CBA journey, a small detour will illustrate that Aleem has put the “social” in social justice for quite some time.

MUSIC, MIXING, FASHION, FOOD AND FAMILY

As a youngster, Aleem brought people together with his calm, encouraging and non-judgmental presence (although Aleem suggests that having one of the first computers and VCRs on the block was probably helpful, thanks to his dad’s love of new technology). They say Aleem was not shy about socializing with others who seemed far different from him, and he could walk into any room and appear completely comfortable.

Aleem’s brother, Jameel, reveals that Aleem was a wannabe fashion and intellectual rebel in his teens. Scarborough in the ’70s was a Wayne’s Worldlike setting, where a young Aleem indulged in the fashion trends of the time with a preference for ripped jeans and chokers. Evolving into a young adult in the ’80s, his aesthetics flowed from his favourite bands (he even sported a short-lived and not entirely successful “rat-tail” during this period). Aleem immersed himself in the anti-establishment lyrical poetry of British new wave bands, such as Tears for Fears. Music videos were the hot new thing. Much Music was the TV channel of choice, showcasing a continuous stream of now-classics from the Brit punk and new wave movements, including the Clash, the Police, the Cars, the Pet Shop Boys, OMD, the Smiths, the Cure, Depeche Mode and so many other acts Aleem and his friends were into.

In this context, Aleem’s brother recalls a brunch with their parents memorialized by Aleem’s announcement that he was going to become an

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022THE ADVOCATE 819

anarchist. He had read every single thing on the subject and was genuine in his plans to shake the establishment in some radical, far-fetched way. The rebellious attitude, coupled with a love of alternative music and funky fashion, soon (and thankfully) found some refinement and sophistication while Aleem attended university.

Nonetheless, family and close friends confirm that the earnest enthusiasm from his formative decades is still alive and well within the Aleem we know. For example, Aleem’s lovely partner, Shelley, notes that the off-duty Aleem continues to absolutely love music and is meticulously honing a passion for cooking delicious meals for family and friends. Aleem prepares his plates to the cascading sounds of his favourite opera music from a beloved CD collection, which inevitably tests the endurance of his partner and his children alike. That one minor issue aside, Shelley shares that Aleem’s default settings of empathy and positivity are intense and infectious.

Indeed, Aleem’s children get a big laugh out of not only his extensive photoshoots (“hundreds of pictures”) of all of the dishes he has prepared, but also his generous emoji use. Hannah and Noah say that every message has way too many emojis. Hannah, however, is proud to share that her dad recently volunteered to speak to her social justice class. After watching him provide a forceful opening statement on behalf of an Indigenous mother alleging egregious mistreatment at the hands of the child welfare system, Hannah was surprised to hear her dad express that he was nervous. Just as expected, her high school classmates did not catch on and instead appreciated Aleem’s passionate yet down-to-earth presentation.

BRINGING SOCIAL JUSTICE TO THE CBABC AND HIS PRESIDENCY

As a longstanding member of the CBABC, Aleem is a familiar face at CBABC events. Aleem joined the CBABC as an articling student and began to exhibit leadership in the Equality & Diversity Committees at the provincial and then national level, ultimately chairing both. He often worked closely with CBABC past-president Jennifer Chow, K.C., in these roles.

Aleem has subsequently co-chaired the Human Rights Law and Social Justice Sections for too many years to count. The annual Social Justice Section Mixer brings together social justice advocates, with the expectation that Aleem will be there, as a welcoming host and convener. Aleem also helped establish the Legal Equity & Diversity Roundtable (“LEADR”) in the mid-2010s, with memorable meetings held in the CLAS boardroom, potluck style, of course. These will resume again soon, under the leadership of Lee Nevens, current LEADR chair and newly elected CBABC second vicepresident.

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022820 THE ADVOCATE

After serving on various committees and sections, Aleem was first elected to CBABC Provincial Council for Vancouver County in 2016 and then to the CBABC board in 2018. He was acclaimed as second vice-president in 2020. Aleem’s presidency will no doubt be informed by his years of work in the social justice sector, especially on the ever-critical issues of equality, diversity and inclusion as well as access to justice, subjects for which his passion remains high. Aleem believes that we are at important inflection points on these matters, post-COVID. His presidency will also require response to the B.C. government’s announced move to a single regulator for lawyers, notaries and paralegals. Aleem plans to make sure the voice of our profession is heard loud and clear, especially on the issues of independence and self-regulation, cornerstones to the fundamental principle of the rule of law.

Aleem seems perfectly suited for this role at this time, and we expect that, in his calm and unassuming manner, he will bring us together to achieve great things.

ENDNOTE

1.[Asst. Editor’s Note: This article was written in advance of the events described here and we have preserved the original tenses in this paragraph.]

2.[Editor’s Note: Levitan was 14 years old when he interviewed John and Yoko on May 25, 1969 at the

King Edward Hotel in Toronto. 38 years later his efforts formed the basis of the short animated film I Met the Walrus nominated for a 2008 Academy Award and available to view online at: <https://www. youtube/watch?v-jmR0V6s3NKk>].

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

THE ADVOCATE 821

Empire Tracing is the oldest Skip Tracing firm in Canada, in opera on since 1967. We help connect our clients with hard to find individuals, such as: Witnesses Plain ffs Defendants Lost Heirs Beneficiaries Pension Recipients Debtors Claimants & Insureds Lapsed Tenants Telephone: 800 661 2800 Email: info@empiretracing.com Website: empiretracing.com Call now or visit our website for more informa on or to start a search today!

Skip Tracing Services Worldwide

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022822 THE ADVOCATE McQuarrie Hunter LLP Suite 1500 13450 102 Avenue Surrey BC V3T 5X3 Email: info@mcquarrie.com Phone: 604.581.7001 Toll-free: 1.877.581.7001 Fax: 604.581.7110 CONTACT MCQUARRIE AT 604.581.7001 MCQUARRIE.COM mcquarrie.com Now with meeting spaces available in Surrey, Vancouver, and Burnaby to better serve our clients throughout BC. LEGAL SERVICES PASSION. TRUST. EXPERTISE. RESULTS.

HALDANE

By Christopher Harvey, Q.C.*

It was said that Richard Haldane was one of “the most powerful, subtle and encyclopaedic intellects ever devoted to the public service of his country”.1 If his country is viewed only as the United Kingdom, this description does him an injustice. The thesis of this article is that he made a greater contribution to the shape of the Canadian constitution than any other judge before or since.

Haldane sat on all the major Canadian constitutional cases that reached the Privy Council between 1911 and 1928. At that time, the balance between the provinces and the Dominion was still in flux. The Fathers of Confederation had been unable to agree whether Canada should have a predominately centralist government or, as Quebec and the Maritimes preferred, decentralist with power predominately in the provinces. The resultant wording of ss. 91 and 92 of the British North America Act, 1867 (now the Constitution Act, 1867) was vague enough to allow for creative judicial interpretation. Lord Watson began the course that Haldane drove home. Both had a strong provincial bias. Critics in the immediate post-Privy Council era called them the “wicked stepfathers of confederation”.2 Economist Hugh Mackenzie of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives puts it succinctly: “The framers of the Canadian constitution set out to create a centralized federation and got what is probably the most decentralized federation in the world”.3

This article will say something about Haldane as a man, a statesman, a philosopher and a lawyer. It will also address whether his constitutional judgments served Canada well or ill.

PHILOSOPHICAL UNDERPINNINGS

Richard Haldane was born into an ancient Scottish family in 1856. He had a nondescript school career in Edinburgh but came alive intellectually when he spent a term at the University of Göttingen at the age of 17. There he developed a lifelong passion for German culture and literature. He

* Christopher Harvey, Q.C., a former editor of the Advocate, delivered this article as a paper at a meeting of the 20 Club in Vancouver on April 7, 2022. He passed away in early September 2022 from COVID-19.

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

THE ADVOCATE 823

immersed himself in the writings of the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel (1770–1831). Anyone who has dipped into Hegel will know that he is notoriously difficult to fathom. Haldane once told a friend that he had read Hegel’s Phänomenologie des Geistes 19 times. Hegel was a major influence in the development of his political philosophy.

Freedom is the dominant principle underlying Haldane’s philosophy of the state. One may ask how the state, which generally functions to restrain freedom so as to prevent anarchy, can be said to foster freedom. Haldane’s answer lay in the conception of the “General Will” (volonté générale for Rousseau; der allgemeine Wille for Hegel). Freedom in its highest form is attained when the laws of a state closely reflect the General Will.

General Will is the will that represents the best interests of the people as a whole as opposed to any individual person’s purely self-interested will. It is not the simple aggregate of voices that flare up from time to time stoked by populists, but is more akin to the will that is particularly evident in times of national crisis when we see a nation pulling together in remarkable ways, willing and performing acts of heroism or self-sacrifice, such as we see in Ukraine today. For Haldane, even in less extreme times, the General Will is still operative, just perhaps less easy to discern. His later judgments in the Privy Council were grounded in what he understood to be the General Will of the people affected.

Haldane wrote a dense work of philosophy entitled The Reign of Relativity. It is filled with serpentine sentences and page-long paragraphs. In it he deals with the distinction between the General Will and the will of the majority, as the following passage illustrates: It is not enough to say that in the ballot boxes a numerical majority of votes for a particular plan was found. For it may become obvious that these votes did not represent a clear and enduring state of mind. The history of the questions at such an election and the changes in their context have therefore to be taken into account. A real majority rule is never a mere mob rule … . Representative and responsible government is thus a complicated and difficult matter, and, if it is to be adequately carried out, requires great tact and insight, as well as great courage; qualities which the people of a country like our own have become trained to understand and to appreciate. No abstract rules for interpretation can take the place of these essential qualities of character in the statesman.4

That optimistic view of enlightened statesmen who control the destiny of a nation is what guided Haldane throughout his life in both politics and the law.

As the title to his treatise indicates, Haldane was to philosophy what Einstein was to physics. In fact the two men corresponded extensively and when Einstein, at Haldane’s invitation, visited England in 1921, Haldane acted as his host. Relativity for Haldane was grounded in the premise that

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

824 THE ADVOCATE

the principles that motivate people cannot be judged against some abstract and fixed standard. His approach was that they had equal value even though they may be fundamentally divergent. That made Haldane a very effective mediator because he could understand and value the principles motivating both sides in a controversy.

His conception of relativity also influenced his theory of the origins and legitimacy of the law, and made him a very effective judge. He saw the common law as grounded in the custom and practices of the people, not derived from the monarch or some code. It was a distinctly bottom-up approach. I will give you my favourite example of this, taken from a case called Attorney-General for British Columbia v. Attorney-General of Canada 5 The issue was whether the right to fish in the sea was vested exclusively in the Crown and exercised as a regal franchise or was a public right belonging to the people. In the hands of any other judge, it might well have been found to be a regal franchise. Not so with Haldane. Without saying so, he found the answer in the General Will of the people, whose customs and expectations informed the common law. The following passage illustrates the point: The legal character of this right is not easy to define. It is probably a right enjoyed so far as the high seas are concerned by common practice from time immemorial, and it was probably in very early times extended by the subject without challenge to the foreshore and tidal waters which were continuous with the ocean if, indeed, it did not in fact first take rise in them. The right into which this practice has crystallized resembles in some respects the right to navigate the seas or the right to use a navigable river as a highway, and its origin is not more obscure than that of these rights of navigation. Finding its subjects exercising this right as from immemorial antiquity, the Crown as parens patriae no doubt regarded itself bound to protect the subject in exercising it, and the origin and extent of the right as legally cognizable are probably attributable to that protection, a protection which gradually came to be recognized as establishing a legal right enforceable in the courts.

If this were the true interpretation of the words of Magna Charta it would indicate that the general right of the public to fish in the sea and in tidal waters had been established at an earlier date than Magna Charta, so that it was only necessary at that date to guard the subject from the temporary infractions of that right by the Crown in the rivers, as well tidal as nontidal, which were covered by the writ de defensione ripariae. But this is a matter of historical and antiquarian interest only. Since the decision of the House of Lords in Malcolmson v. O’Dea (10 H.L.C. 593), it has been unquestioned law that since Magna Charta no new exclusive fishery could be created by Royal grant in tidal waters, and that no public right of fishing in such waters, then existing, can be taken away without competent legislation. This is now part of the law of England, and their Lordships entertain no doubt that it is part of the law of British Columbia.

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

THE ADVOCATE 825

HALDANE, THE MAN

Richard Haldane was called to the bar in London in 1879. Eleven years later, at age 33, he became the youngest Q.C. in 50 years. In 1886, at age 29, he was elected to Parliament. In 1905, he entered the Liberal Cabinet as Secretary of State for War, a post he held until 1912. He is credited with reorganizing an army that had changed little since the time of Napoleon. The British Expeditionary Force that held off the invading German Army from Paris in 1914 was his creation.

In 1911, he became Viscount Haldane of Cloan (Cloan being his home estate in Scotland). In 1912, he was appointed Lord Chancellor—for the first time. As a Germanophile, he fell out of favour in 1915 but was re-appointed Lord Chancellor in the Ramsay MacDonald government in 1924.

On the personal side, Haldane was a large man who enjoyed his food and enjoyed company. He was described as having the mind of Socrates and the body of Nero.6 In Haldane, even the young Churchill met his match: Winston Churchill one day ran into him in the lobby of the House, tapped him on his great corporation and asked, “What is in there, Haldane?” “If it is a boy,” said Haldane, “I shall call him John. If it is a girl, I shall call her Mary. But if it is only wind, I shall call it Winston.”

That story was recounted by the founder of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Lionel Curtis, who also said of Haldane that:

To few if any of its members does the Royal Institute of International Affairs in its early years owe such as deep a debt as it does to him. His sympathy and advice was always unfailing and also his active help when needed. He seemed to live for public service … . There never was a man whose octave was quite so wide. Was there ever before a profound metaphysician who could also give the nation the army which alone enabled it to survive the greatest struggle in history.

In light of all he did for his country, it might be thought that he had little time to devote to his practice at the bar, but Haldane was a relentless workaholic. He worked tirelessly and got by on only about four hours of sleep a night. He threw himself into his cases. By 1905, his busy practice earned him the equivalent of C$4 million in today’s value.

I will mention only one case—one that he lost, probably because he knew far too much about it and, for that reason, lost his audience. The issue concerned the union of the Free Church of Scotland with the United Presbyterian Church in 1900 to form the United Free Church of Scotland, for whom Haldane acted. Dissenting members claimed more than £2 million of the church’s money, arguing that a change in the doctrine of predestination arising from the union undermined the original constitution of the Free Church. Haldane marshalled vast scriptural knowledge for his rebuttal. The librarian of the House of Lords described the scene in court as follows:

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

826 THE ADVOCATE

The Chancellor [Lord Halsbury], manifestly hostile to the Free Church’s position, is red with effort, mental and physical, of finding holes in Haldane’s polished armour. Lord Alverstone, perfectly bland, with glassy eyes, is an evident Gallio, to whom all this ecclesiastical metaphysic is unintelligible and insane. Lord James of Hereford chafes under it, constantly snapping out, “I say it without irreverence but,” or “Well, well, Mr. Haldane, but in the name of common sense … ”, and Haldane, flapping back the side of his wig, replies, “My Lord, we deal not with the dictates of common sense, but with a mystery.”

Haldane later lamented that the Law Lords had not been Scotsmen, to whom his arguments—he believed—would have seemed as clear as day. Nevertheless, he won on the doctrinal point, but lost on a trust point. The result was disastrous, stripping the Church of all its property and landing a huge liability for costs on the individual trustees. Most barristers would simply have moved on to the next case, but Haldane refused to let such an injustice stand. He organized a subscription to which he made the original sizeable donation. Then he brought into play his powerful political contacts. He spent a weekend at the country home of the Prime Minister, enlisting his support, followed by the support of the Archbishop of Canterbury and others, for an Act of Parliament to redress the situation—which passed with little opposition.

THE CANADIAN CONNECTION

Haldane had his first brief from Canada—an application for leave to appeal by Quebec—in 1883, when he was only four years of call. Between 1894 and 1904, he acted on behalf of Canadian provinces seven times. This was interspersed with an enviable variety of other cases from all parts of the Empire. In his autobiography, he wrote: I remember … one fortnight within which, towards the end of my time [at the bar], beginning with a case of Buddhist law from Burmah. I went on to argue successively appeals concerned with the Maori law of New Zealand, the old French law of Quebec, the Roman-Dutch system of South Africa, the Mohammedan law and then the Hindu law from India, the custom of Normandy in a Jersey appeal, and Scottish law in a case from the North.7

In 1911, while still Secretary of State for War, Haldane was appointed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Over the course of the next 17 years, he heard 32 Canadian appeals, delivering 19 of the judgments—a formidable contribution.

As I intimated earlier, the balance struck by the Fathers of Confederation in ss. 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867 ebbed and flowed through the decades of judicial interpretation. The words themselves represent a compromise between those who favoured a strong central government and oth-

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

THE ADVOCATE 827

ers who favoured decentralization. The resultant wording favours a centralist interpretation. The all-important residual power, for example, appears intended to reside in the “peace, order and good government” clause in s. 91 (“POGG”), and the first Privy Council cases—before Haldane’s time—interpreted it as such. Federal temperance legislation, for example, was upheld under this head, although controlling the nation’s drinking habits can hardly be said to be a national emergency or a matter of pressing national concern.8

This centralist leaning conflicted with Haldane’s view, based on Hegelian political philosophy, that the people governed are served best by government that is close to them. Everything he had heard at the bar from the provinces backed up the view that power had to get closer to the wellsprings of sovereignty: the local groups and associations that expressed the General Will. In the Canadian context, this favoured government by provincial legislatures rather than by Parliament.

Haldane did not hesitate to adapt the law to his perception of the General Will in Canada. There is little doubt that he believed that the British North America Act, 1867 in its traditional interpretation—i.e., the interpretation that prevailed before his predecessor Lord Watson—was not representative of the source from which his own authority as a judge came—being, in his view, the authority of public opinion. Speaking in Montreal to a joint meeting of the Canadian and American Bar Associations in 1913, he quoted the famous words of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in support of his point of view: The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intentions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow men, have had a good deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed. The law embodies the story of a nation’s development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics.9

Haldane might have added that a nation’s constitutional development cannot be constrained by the static words of an Act of Parliament.

Lords Watson and Haldane dominated Canadian appeals to the Privy Council from 1880 to 1899 (Watson) and 1911 to 1928 (Haldane). They shared a preconceived notion about the proper form of a federal system. Haldane described the process of adapting the Canadian constitution (modestly omitting his own role in it) in a speech delivered to the Cambridge University Law Society in 1923:

At one time, after the British North America Act, 1867 was passed, the conception took hold of the Canadian Courts that what was intended was to make the Dominion the centre of the government in Canada, so that its

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

828 THE ADVOCATE

statutes and position should be superior to the statutes and position of the Provincial Legislatures. That went so far that there arose a great fight; and as the result of a long series of decisions Lord Watson put clothing upon the bones of the Constitution, and so covered them over with living flesh that the Constitution of Canada took new form. The Provinces were recognized as of equal authority co-ordinate with the Dominion, and a long series of decisions were given by him which solved many problems and produced a new contentment in Canada with the Constitution they had got in 1867.10

The process of favouring provincial over federal power was worked out through restrictions on the s. 91 powers relating to POGG, criminal law and trade and commerce. Think truckers occupying the streets of Ottawa when you read the following passage from Haldane’s judgment in Fort Frances Pulp & Paper Co. v. Manitoba Free Press Co.: Their Lordships, therefore, entertain no doubt that however the wording of Sections 91 and 92 may have laid down a framework under which, as a general principle, the Dominion Parliament is to be excluded from trenching on property and civil rights in the Provinces of Canada, yet in a sufficiently great emergency such as that arising out of war, there is implied the power to deal adequately with that emergency for the safety of the Dominion as a whole.11

In Toronto Electric Commissioners v. Snider, 12 Haldane returned to the POGG emergency power. He described it as applying only to “extraordinary peril to the national life of Canada”, circumstances that are “highly exceptional” and “a menace to the national life of Canada that is so serious and pressing that the National Parliament was called on to intervene to protection the nation from disaster”.13

Earlier this year the federal government, relying on its POGG power, invoked the Emergencies Act to give it control over the property and civil rights of a gaggle of truckers in Ottawa. The premier of Quebec responded by saying that the federal government should not try to apply the Emergencies Act in Quebec. One could translate that to mean that the application of the Act to the situation created by the truckers would be considered by the Government of Quebec to be ultra vires as trenching on provincial power over property and civil rights as expressed in the judgments of Lord Haldane.

CRITICISM AND DEPARTURES FROM HALDANE’S JUDGMENTS

After Haldane’s death in 1928, the Privy Council, in a series of decisions arising out of Parliament’s “Canadian New Deal” legislation, held that the Great Depression did not count as an emergency, and as a result, their lordships struck down the legislation. It is interesting to speculate as to whether Haldane’s conception of General Will would have caused him to expand the

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022THE ADVOCATE 829

emergency doctrine in this instance. In any event, the legislation was struck down and the Privy Council came to be viewed by leading constitutional scholars (mostly from central Canada) as a liability that had not served Canada well.14

The Supreme Court has decided that it is not bound by decisions of the Privy Council, and it has explicitly refused to follow a Privy Council precedent in at least three constitutional cases.15 Nevertheless, the main lines of authority established by the Privy Council, and especially the wide scope of provincial power over property and civil rights, have not been disturbed. The two most important federalism cases since the abolition of appeals to the Privy Council in 1949, being the Patriation Reference and the Secession Reference, actually expanded provincial powers.16

FINAL JUDGMENT

In recent decades, the criticism of Haldane’s provincial bias has cooled. The late Peter Hogg wrote that:

[W]e believe that Canada’s federal system is bound to be less centralized than those of the United States and Australia. It follows that, although the Privy Council did favour the provinces, in the end, and perhaps more by accident than design, Canada was, on the whole, not badly served by the Privy Council.17

The late Ken Lysyk went further, expressing the view that “on the whole, the Privy Council did a creditable job of interpreting our Constitution in a way which preserved a balance in the Canadian federation”.18

What both these learned men missed, however, is that Haldane’s appreciation of the need for a provincial bias in the Canadian constitution was a deliberate choice based on Hegelian philosophy and a careful assessment of the General Will in Canada. Both Hogg and Lysyk saw it as a kind of accident that Haldane got it right. Hogg said “perhaps more by accident than design”. Lysyk said:

[T]he jurisprudence passed on to us by the Privy Council, so roundly condemned as ignorant or perverse, may in fact have reflected an appreciation that an attempt to impose complete domination from the centre would have imposed strains on the Canadian federation which, quite simply, would have proved unacceptable.19

Professor Hogg appears to have thought that Haldane’s basic principle that government power is best applied at the local level is a modern invention:

Another idea that has gained adherents, especially in Western Europe (where nations struggle to accommodate a European Community), is “subsidiarity”. Subsidiarity is the principle that decision-making should be kept as close to the individuals affected as possible.20

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022830 THE ADVOCATE

This, I hesitate to say, ignorance does an injustice to the work done by Haldane in shaping the Canadian constitution.21 It is not at all a stretch to consider that Haldane correctly identified the forces at work in Canada and moulded the law accordingly. In doing so, he may even be credited as having preserved the unity of Canada. Pierre Trudeau wrote in 1968 (before his own conversion to centralism), “[I]f the law lords had not leaned [in the direction of the provinces], Quebec separatism might not be a threat today: it might be an accomplished fact”.22

With that thought in mind, fast forward to 1995. By a knife-edge margin of 50.6/49.4 per cent, Quebec voted against secession. As we have seen, Haldane was convinced that strong states are built on a sense of autonomy among their constituent parts. If one agrees with that, it is hard to deny the hypothesis that Haldane, through his judgments in the Privy Council, was instrumental in the preservation of a unified Canada. Had his critics in the form of Laskin, Forsey and Scott prevailed, the knife-edge margin in the secession referendum might well have been reversed.

ONE MORE THOUGHT

Is it perhaps the case that the social and political discontent that gave rise to the truckers’ rebellion in Ottawa and to the rise of Trumpism in the United States originates in a feeling that those who hold the destiny of our country in their hands have become disconnected from the General Will of those they govern? Is there perhaps a similar feeling among litigants that the courts have become inaccessible and that the judges have lost touch with the General Will of the populace?

If so, we may need another Haldane to remind us that the ultimate source of legitimacy for both government and the law is the General Will of the people.

ENDNOTES

1. Obituary of Lord Haldane, The Times (20 August 1928).

2. Eugene Forsey, “Canada: Two Nations or One?” (1962) 28:4 Can J Econ Polit Sci 485.

3. “Equalization and the Birth of a ‘Boneless Wonder’”, iPolitics (17 February 2013), online: <ipolitics.ca/ 2013/02/17/equalization-and-the-birth-of-aboneless-wonder/>.

4. Richard Haldane, The Reign of Relativity (London: John Murray, 1921) at 371.

5. [1914] AC 153.

6. See John Campbell, Haldane: The Forgotten Statesman Who Shaped Britain and Canada (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020) at 2.

7. Richard Haldane, An Autobiography (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1929) at 43.

8. Russell v The Queen, [1882] 7 AC 829.

9. Richard Haldane, Higher Nationality: A Study in Law and Ethics (Dutton, 1913) at 56–57.

10. Lord Haldane, “The Work for the Empire of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council” (1923) 1 Camb LJ 143 at 150.

11. [1923] AC 695 at 703–04.

12 . [1925] AC 396.

13. Ibid at 412.

14. See e.g. Bora Laskin, “Peace, Order and Good Government Re-Examined” (1947) 25 Can Bar Rev 1054; Frank R Scott, “Centralization and Decentralization in Canadian Federalism” (1951) 29 Can Bar Rev 1095; Forsey, supra note 2.

15. The first case is Re Agricultural Products Marketing Act, [1978] 2 SCR 1198 at 1234. The second is Re

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022THE ADVOCATE 831

Bill 30 (Ont Separate School Funding), [1987] 1 SCR 1148 at 1190–96, overruling Tiny Roman Catholic Separate School Trustees v The King, [1928] AC 363. The third is Wells v Newfoundland, [1999] 3 SCR 199 at para 47, overruling Reilly v The King, [1934] AC 176.

16. Reference re Resolution to Amend the Constitution, [1981] 1 SCR 753; Re Secession of Quebec, [1998] 2 SCR 217.

17. Peter W Hogg & Wade K Wright, “Canadian Federalism, the Privy Council and the Supreme Court: Reflections on the Debate about Canadian Federalism” (2005) 38:2 UBC L Rev 329.

18. Kenneth M Lysyk, “Reshaping Canadian Federalism” (1979) 13 UBC L Rev 1 at 5.

19. Ibid at 5.

20. Hogg & Wright, supra note 17.

21. Even in his own day, Haldane was underappreciated. When word reached him that Sir Charles Fitzpatrick CJC considered the Privy Council judgments in Canadian cases to be “perfunctory and cavalier”, Haldane responded sharply that “I have bent the whole strength of our tribunal on cases from Canada even to the sacrifice of English work in the House of Lords of two judges—which was what the Imperial Conference asked for … and it certainly never gave more time or pains to Canadian cases”. See Campbell, supra note 6 at 312.

22. Pierre E Trudeau, Federalism and the French Canadians (Toronto: Macmillan, 1968) at 198.

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

832 THE ADVOCATE

ONTARIO COURT OF APPEAL DENIES PRECONCEPTION

MEDICAL DUTIES TO FUTURE CHILDREN: WHY BRITISH COLUMBIA SHOULD NOT FOLLOW ONTARIO’S LEAD

By Aminollah Sabzevari*

In Florence v. Benzaquen, a majority of the Ontario Court of Appeal (“ONCA”) closed the door on a doctor owing any duty of care to future children for alleged negligence that occurred during preconception care.1 The dissenting justice would have kept the door open to a claim, if only just a crack. 2 The case curtails the development of Ontario’s tort law in this area just as the role of preconception care is increasing in importance.

Whether a duty exists to born-alive children for preconception care matters because children cannot rely entirely on their parents’ claim for compensation, particularly when they suffer lifelong injuries or when parents fail to manage their own claims in the best interests of the children. British Columbia should not follow Ontario’s lead, as there is a sound legal basis for a doctor to owe a duty of care to a born-alive child for preconception care.

THE DECISION

The majority followed and applied the reasoning from past ONCA decisions to confirm that a lack of proximity and the existence of residual policy concerns prevent the finding of a duty of care to a born-alive child.3 The ONCA identified three arguments against the proposed duty of care: (1) the necessarily indirect relationship between the child and the doctor; (2) an inherent conflict of interest for the doctor between the patient and the future child; and (3) an undesirable chilling effect on doctors.4

* The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the views of the Department of Justice Canada or the Government of Canada. This article was made possible in part by a graduate fellowship provided by the Law Foundation of British Columbia during the author’s graduate studies.

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

THE ADVOCATE 833

As noted in the dissent, the majority’s arguments used against a preconception duty of care would similarly apply during pregnancy.5 However, these arguments do not prevent a doctor from owing a duty of care to a born-alive child for medical care provided during pregnancy. It is difficult to draw a dividing line based on the identified arguments between the following two scenarios: medical care relating to pregnancy sought by a pregnant patient (“prenatal care”) and medical care specifically sought by a patient intending to become pregnant (“preconception care”).

Analogous Category of Negligence Not Considered by the ONCA

When there is a previously established duty of care, proximity is normally present and the second stage of the Anns/Cooper test will rarely need to be addressed.6 The difficulty in distinguishing between prenatal care and preconception care indicates that the former may be an analogous category that may be relied upon in establishing a duty of care in the latter scenario. If a court still proceeds with an Anns/Cooper analysis, the existence of the prenatal care category helps to lessen the gap in establishing a duty of care for preconception care by showing that the three arguments identified by the ONCA do not preclude recognizing the proposed duty of care.

Necessarily indirect relationship

The necessarily indirect argument fails to distinguish preconception care from prenatal care and in some ways post-birth care given to infants in the custody of their parents. As noted by the B.C. Supreme Court (“BCSC”), during the entire pregnancy the “mother acts as ‘intermediary’ between physician and fetus, and makes medical decisions for the fetus and herself”.7 There is nothing inherently problematic about this intermediacy in the prenatal situation. The doctor is not in a position to give instructions to or advise a fetus or even a newborn child; instead, the doctor must rely on conveying information to the child’s parents.

The patient is under no duty before pregnancy or during pregnancy to the future child, but their shield from liability is not a bar to the doctor’s duty to the future child, whether for preconception care or prenatal care. The doctor’s reliance on the patient in relation to following medical advice is reflected in the standard of care, not the formation of a duty. In relation to post-birth care, parents owe duties to infants, while doctors and the state do have legal means of gaining custody of the child and providing medical care in the child’s best interests. However, the vast majority of infant medical care still involves doctors relying on parents, a reliance reflected in the standard of care involved in meeting the duty owed by the doctor to the newborn child.

VOL. 80 PART 6 NOVEMBER 2022

834 THE ADVOCATE

An inherent conflict of interest

In Paxton v. Ramji, the ONCA referenced the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) case of Syl Apps Secure Treatment Centre v. B.D. as an example of an inevitable conflict of interest.8 In Syl Apps, the SCC identified the potential for conflicting duties as a policy consideration and the deciding factor preventing a relationship of proximity in that case.9 The issue was whether a treatment centre, which was treating a child apprehended by the Children’s Aid Society, owed a duty of care to the family of the child in addition to the statutory duty owed to the child. The SCC found there would be an inevitable conflict of interest if the treatment centre owed a duty of care to the family. The ONCA similarly classified the proposed duty of care owed to a future child as creating an irreconcilable conflict of interest for the doctor, who already owes a duty of care to the patient seeking preconception care.10

This classification can be challenged in two ways: by distinguishing Syl Apps and by restricting the nature of the proposed preconception duty. On the first point, the service provider was the agency with power in Syl Apps, in an “inherently adversarial” context where conflict was inevitable in many (if not most) cases, and the finding of lack of proximity was reinforced by legislative policy.11 The BCSC distinguished Syl Apps from the prenatal medical care context, which arguably distinguishes it from preconception medical care as well:

[Syl Apps] did not involve potential conflicts between the interests of mother and fetus ... Since the parents were in an inherently adversarial relationship with the child protection authorities, such a duty would have created an intolerable conflict. As both case authorities and obstetrical medicine recognize, the relationship between mother and fetus is entirely different. Its potential to interfere with a physician’s ability to fulfill a duty of care to the fetus is no different from that of a mother’s role in relation to the medical care of her infant child, to whom the physician undoubtedly carries a duty of care.12

An undesirable chilling effect