For All the Saints: A Living Rhythm of Sanctity in the Church’s Liturgy

By Father Ryan Rojo

The saints stand as beacons of faith, courage, and unwavering devotion. Venerated across cultures and centuries, these extraordinary individuals are remembered not only for their piety, but also for the impact they had on the Church, inspiring subsequent generations of believers. To appreciate the lives, legacies, and enduring relevance of these holy figures, it is advantageous to consider the experience of the saints in the Church’s prayer, especially in the sacred liturgy. Much can be gleaned about the Church’s theology of the saints from the texts of her liturgy, particularly the texts for the Solemnity of All Saints, celebrated annually on November 1. In the texts of this particular

Mass, we find an exposition of the perennial teachings of our faith with respect to these heavenly intercessors, confirmed elsewhere in the Church’s tradition.

Saints—Reflections of Christ

The Collect, or opening prayer, for Mass on the Solemnity of All Saints begins by venerating the merits of all the saints.1 In Catholic theology, merit refers to the rewards granted the saints as part of the divine generosity. The merits of the saints, however, refer us to the witness and example of Christ, a sentiment confirmed in the Praenotanda of the Roman Martyrology: “Over the course of time, the lives of the Saints shine forth as a continuation of the memory of the life of Christ, dem-

A small sampling of the Adoremus Bulletin in the archives of Sacred Heart Seminary and School of Theology, Hales Corners, WI. The Adoremus Bulletin has a distinguished history of liturgical renewal, a legacy that continues to inform and inspire its ongoing work.

The Church is directing our attention to heaven, couching our celebration of the saints in the larger experience and hope of heaven, our true home.

Wonder—Essence of Worship

Pope Francis unapologetically takes his inspiration from Romano Guardini, who poses the penetrating question: are modern people capable of “committing a liturgical act?” The response is a resounding “Yes!” We have the capacity, but we may not always understand how to do it. The Holy Father’s conviction that wonder (stupor) is related to worship provides an entrée into engagement with the liturgy. It is important to note that stupor (wonder, astonishment) is a reaction to something experienced. This idea is essential because it highlights our response to the initiative taken by God;

prehension. Its etymology suggests something richer, something more compelling. Scholars consider the root of mystery to be “muo,” which literally means “to shut the mouth.”2 The English cognate “mute” is derived from the same root. In other words, mystery is used to characterize our encounter with God as him by whom we are dumbfounded, rendered speechless. It takes our breath away. No single word can ever be found to express the inexplicable.

This does not mean that we should not try to put words to the experience; the nature of the encounter, as well as the nature of human beings, compels us to share what we have experienced. Faith seeks understanding. Fides quaerens intellectum.3 What it indicates

worship is fundamentally a response to the Source of our benefits. It also reinforces the sense of something “beyond” ourselves, bigger than ourselves, especially in monotheistic religions.

The association of worship with wonder is inscribed in the etymology of the Greek term for worship, sebein.1 Names such as Sebastian and Eusebius come from this word. Eusebius means “he worships well,” while Sebastian means “one who is revered.” In the New Testament sebein is usually translated as “worship.” And yet this term has a more ancient signification. It suggests wonder, awe, astonishment at what one sees or encounters; try to imagine the expression on the face of an astonished person: that is the essence of sebein. It happens like a flash of lightning (fulgura) as a wordless admiration arising from the deepest dwelling of a person: a soundless “Wow!”

The word musterion (μυστήριον) is closely related to this idea. It is important to reflect on the origin of the word because if the simplistic yet typical answer is that mystery means the divine cannot be understood, we might leave it there and simply give up. But the point of calling it mystery is not to solve a puzzle, but to react (“Awesome!”) to something that is beyond our com-

is that we must not confuse or conflate the Divine encounter with speaking about the Divine encounter. Experience and an explanation are radically different phenomena.

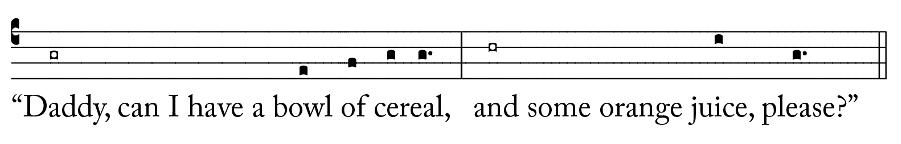

By the time Eli was three years old, his parents had already been singing Morning Prayer for years. One morning as they were finishing Lauds, Eli approached his father, singing:

He may not have been able to define what “Lauds” is, but he knew the seriousness of his parents’ prayer and he intuitively learned that the best way to ask is in song. Perhaps someday he will discover that he was singing in Mode 8. That realization will ignite curiosity and provoke more questions. Do we have the capacity? Absolutely. Whether we have the will to cultivate this capacity is a different question.

Astonishment at the Salvific Plan

There is, then, intellectual work to be engaged in: before, during, and after a liturgical celebration. Cateche-

sis, proclamation, mystagogy, can each foster a greater awareness, a deeper appreciation, a fuller engagement. There is a double marvel in the mystery of our redemption that must be acknowledged. The first marvel is that God should love us so much as to send his Son (his only one) to free us from our enslavement to sin. The second source of astonishment is that the chosen way for our liberation should be the dramatic Passion of Christ. Thus, genuine prayer is grounded not only in the fact that God creates and sustains us, but also in the profound Christian message that in our fallen state God sent his Son to redeem us: “While we were still sinners Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8). The biblical narratives recited at liturgical worship rehearse these themes. Theologians grappling with the concepts con-

“Do we have the capacity for wonder? Absolutely. Whether we have the will to cultivate this capacity is a different question.”

tinually renew them, providing insight for each new generation. And yet, the Holy Father draws attention to the aspect that cannot be forced by the Bible, the theologian, or even the pastor. Pope Francis insists on the individual responsibility to embrace the salvific message and to allow oneself to respond in wonder and awe to the magnificent work of God.

Perceptible Signs

The image which the Pope uses in paragraph 24 is particularly evocative. In pointing out that there is an “ocean of grace that floods every celebration,” he is asserting that the presence of grace is objective, whether we recognize it or not—in other words, it is waiting to be discovered. The inability to delight in the Paschal Mystery, available in perceptible, sacramental signs, would be akin to wearing a raincoat in a walk along the beach: we would never get wet, but then again, we would never be refreshed by the ocean’s spray or washed clean in the flood. Paying attention to the perceptible signs opens us up, attunes us to the treasure of the sacramental symbols of the liturgy. Moreover, the discovery of the connection between the perceptible sign and the reality of our salvation results in a kind of delight that leaves us positively stupefied. If we are not able to do this, or if we do not know how to do it, or are unwilling to engage it, the other prescriptions for improving the liturgy (better music, more inspiring preaching, shinier churches) will necessarily fall short. Even if every performative element of the celebration was perfect, “that would not be enough to make our participation full” (23). If wonder is the essence of worship, we must not reduce sincere prayer to a static formula.

Liturgical engagement is predicated on the universal human phenomenon of our capacity for wonder. Reflecting on the phenomenon can assist, but it cannot replace the obligatory effort of each person to be attentive to the things being celebrated. Without that effort, no book in any library will be able to make it happen. And yet, skills can be perfected, perception can be sharpened, abilities can be honed.

“The inability to delight in the Paschal Mystery, available in perceptible, sacramental signs, would be akin to wearing a raincoat in a walk along the beach: we would never get wet, but then again, we would never be refreshed by the ocean’s spray or washed clean in the flood.”

The Escape Room

One learns much in an escape room: much about oneself, group dynamics, and teamwork. One learns the value of attention to detail, of observation, and of the importance of synthesis.

Neophytes locked in an escape room can be easily discouraged, especially in the early minutes: everything is new, all seems strange. And yet, practically everything we need to fully engage is already present.

AB/BRUMMOND. CEILING OF LA SAGRADA FAMILIA IN BARCELONA, SPAIN.

“Mystery” is used to characterize our encounter with God as him by whom we are dumbfounded, rendered speechless. It takes our breath away. No single word can ever be found to express the inexplicable.

AB/CATHOLIC CHURCH OF ENGLAND AND WALES ON FLICKR

A more ample understanding of “mystery” (mysterium) is one of the objectives of Pope Francis’s 2022 apostolic letter Desiderio Desideravi, on the liturgical formation of the faithful.

On the other hand, an uncooperative player could be resolved to passively wait until the attendant returns 60 minutes hence to unlatch the door; such an attitude disables the group.

Meanwhile, other team members have sprung into action from the first moments. Some get the big picture, others look for patterns, still others search for other clues, assessing, decoding, correlating. Each one in his or her own way contributes to the functioning of the whole.

Continued from NEWS & VIEWS, page 2

Likewise, the liturgy provides nearly everything that is necessary. What it cannot supply is personal willingness to engage the mystery. It is up to each one individually, and within the power of the group collectively, to be immersed in what Pope Francis calls “the ocean of grace that floods every celebration.” There are so many reasons to give thanks, so many insights and connections to be revealed, such opportunity to marvel at what God has done for us and to participate in the mystery, the awesome fact of Christ’s Body given for us. Unfortunately, for some Mass-goers, the Sunday celebration is the experience of being locked in an escape room for 60 minutes: they share the strategy of letting the time pass until the doors are re-opened and can finally say with a sigh of relief, “Thanks be to God.”

In Every Age

We must be reminded that we do, in fact, have a capacity for symbol. Even today, we still wonder at the world around us—we are able to make connections, consociations. The monastic tradition has repeated the idea: Si cor non orat in vanum lingua laborat (“If the heart does not pray, the tongue labors in vain”). What is needed is not a new doctrine, not new innovations. What is needed is an embrace of the Pope’s conviction that each one should make the prayer his own. This is why Romano Guardini’s insight was so important. If the focus is external performance and visible participation, not only

Word on Fire Announces New Bishop Barron Documentary

By Francesca Pollio Fenton

CNA—Word on Fire announced August 4 that a new documentary by Bishop Robert Barron is underway that will showcase the beauty of Catholic cathedrals and how they guide the faithful to the divine.

In the announcement, Bishop Barron—who also serves as Bishop of the Diocese of Winona-Rochester, MN—explained that the inspiration for the documentary came after the tragic fire that destroyed part of the historic Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris.

In April 2019, Notre Dame’s iconic roof and spire were engulfed by a fire, the causes of which have yet to be determined. Its main structure was saved, along with many of its priceless contents, but the restoration project was monumental, amounting to almost 700 million euros ($740 million). The historic cathedral reopened on December 7, 2024.

Bishop Barron recalled that the response from people all around the world was “intriguing” to him and he “had a sense that people knew the fire was threatening to destroy something of great spiritual value—even if they were not faithful themselves.”

After this, Bishop Barron wrote a script for a documentary that explored the idea of the spirituality of cathedrals and their ability to draw in even those who do not believe in God or practice any faith.

The documentary will take viewers to the French cathedrals of Amiens, Chartres, Notre-Dame, Reims, and Saint-Denis to explore these medieval cathedrals more in depth. It will combine history, theology, art, and Scripture to show the significance of cathedrals and answer the question: What is it about the beauty of a cathedral that is so transcendent?

Bishop Barron said he believes the documentary will have “great evangelical value.”

“My hope is that this film can have a similar impact by drawing people into the beauty of our faith through the intrigue of these impressive buildings,” he said.

Bishop Barron has released several documentaries over the years including the “Catholicism” series, which took viewers to 50 locations throughout 15 countries to reveal the fullness of the Catholic faith, and the “Pivotal Players” series, which dove into the lives of 12 of the most influential Catholic figures in history.

A release date for the new documentary has not been announced.

Liturgical Considerations for All Saints Day and All Souls’ Day 2025

By the USCCB Secretariat of Divine Worship

In 2025, the Solemnity of All Saints on November 1 falls on a Saturday, with the Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed (All Souls’ Day) taking place on the following Sunday, November 2. The Secretariat of Divine Worship reminds all concerned about the situation regarding the correct Mass and Office to be used during November 1–2.

Both All Saints Day and All Souls’ Day are ranked at no. 3 on the Table of Liturgical Days. Thus, on Friday evening, October 31, Evening Prayer I of All Saints is celebrated. On Saturday, November 1, both Morning

may it not help, but the obsession with externals can become a debilitating obstacle.

Pope Francis is not the first to call for deeper engagement with the liturgy. Rather than be mystified by the mystery of it and dismiss it as too complicated, as too far out, as too difficult to understand, the Holy Father reminds us to be amazed by it, accepting that it is eminently accessible. Perhaps that fact, that this is easier said than done, explains why the call must be repeated generation after generation.

Father Eusebius Martis is a Benedictine monk of Marmion Abbey, a sacramental theologian, and international lecturer. He teaches at the Ateneo Sant’Anselmo and the Pontificio Instituto Liturgico, Rome. He is former director of Sacred Liturgy and Associate Professor of Sacraments and Liturgy at the Pontifical College Josephinum in Columbus, Ohio. He was Director of the Liturgical Institute at the University of Saint Mary of the Lake (2004-2015) and Associate Professor of Sacramental Theology in the Department of Dogmatic Theology as well as Chair of the Department of Liturgy and Music at the University of Saint Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary (2002-2015).

1

2

3 See Anselm of Canterbury, Proslogion, Book I.

and Evening Prayer II of All Saints Day are celebrated, though for pastoral reasons where it is the custom, Evening Prayer II may be followed by Evening Prayer for the Dead. For Sunday, November 2, the Office for the 31st Sunday in Ordinary Time is said, especially in individual recitation; the Office of the Dead may be used, however, if Morning or Evening Prayer is celebrated with the people (see Liturgy of the Hours, vol. IV, Proper of Saints, November 2).

On Friday evening, Masses are those of the day since All Saints Day is not a day of precept this year and thus may not be anticipated. On Saturday evening, any normally scheduled anticipated Masses should be for All Souls’ Day. (If desired for pastoral reasons, a Mass of All Saints Day outside the usual Mass schedule may be celebrated on Saturday evening.) The following chart may be helpful in this regard:

Date Evening Mass Liturgy of the Hours

Saturday, November 1, 2025

Sunday, November 2, 2025

All Souls (anticipated) Morning & Evening Prayer II of All Saints (EP of the Dead optional after EP II of All Saints)

All Souls Individual recitation: Morning & Evening Prayer II of 31st Sunday in Ordinary Time Celebrated with the people: Office of the Dead

Since Saturday is a common day for the celebration of Marriage in the United States, it should also be noted that Ritual Masses are forbidden on All Saints Day (General Instruction of the Roman Missal [GIRM], no. 372). While the Ritual Mass for the Celebration of Marriage is forbidden, the Mass of the day with the ritual itself and the nuptial blessing could be celebrated. Alternatively, the Order of Celebrating Matrimony without Mass could also be used if the celebration of Marriage is to take place on this day. (Ritual Masses are also forbidden on All Souls’ Day.) As a reminder, All Saints Day is not a holy day of obligation this year, owing to the 1992 decision of the USCCB abrogating the precept to attend Mass when November 1 falls on a Saturday or Monday. Therefore, funeral Masses may be celebrated on this day (see GIRM, no. 380).

Excerpted from the May 2025 Newsletter of the Committee on Divine Worship. © 2025 United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Washington, DC. All rights reserved.

The Jewish Roots of the Catholic Altar: The Altar of Incense (Part III)

By Brant Pitre

One of the distinctive features of Roman Catholic worship is the use of incense during the Holy Mass, especially in its more solemn form. Despite the familiarity of using incense in worship— think here of the expression “smells and bells”—many Catholics still wonder: Why do we use incense in Mass? Where does it come from? What is the deeper meaning of this odiferous smoke?

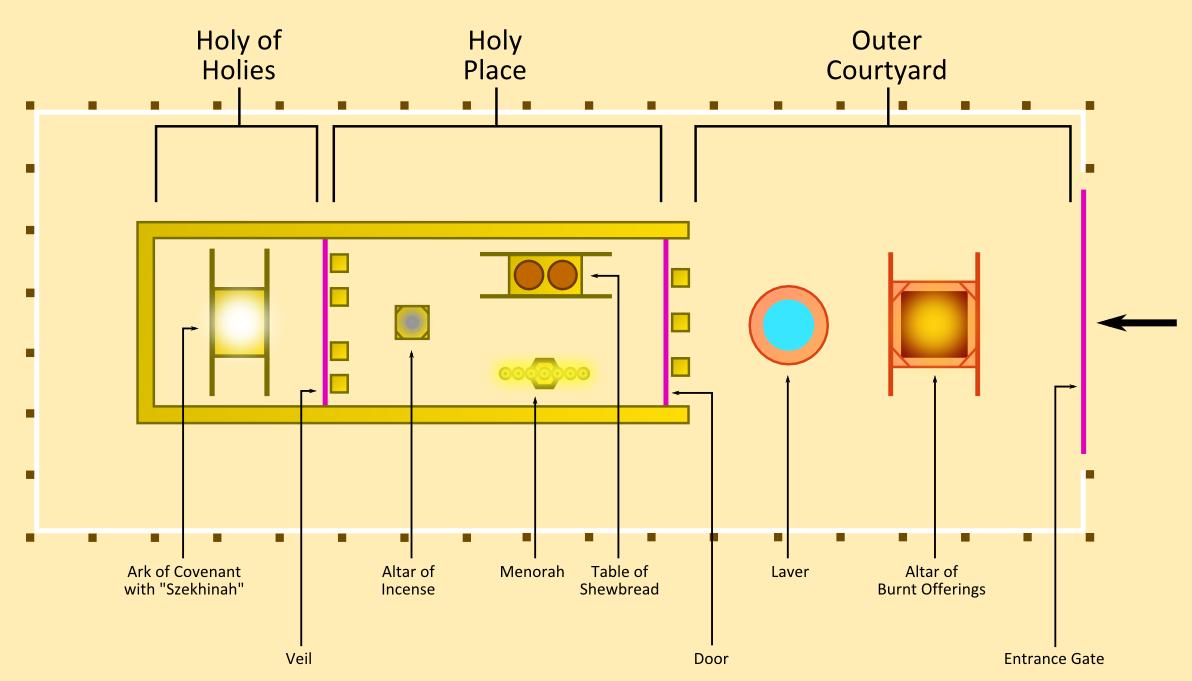

In order to answer these questions, in this article, we will take a closer look at the third example of an ancient Jewish altar that sheds light on the Catholic altar of the Eucharistic sacrifice. I am speaking here of the golden “altar” of incense that the Old Testament describes as part of the Tabernacle of Moses (Exodus 30:1-10), and later, the Temple of Solomon (1 Chronicles 28:18). Here is a diagram of its location in the Tabernacle:

incense” on the golden altar as a “perpetual” offering to the God of Israel. Clearly, from an Old Testament point of view, incense is an important, even integral part, of divine worship in the Mosaic Tabernacle.

Smoke of Incense, Fire of Prayer

Why is incense so sacred and significant? And why does God insist that the incense have a “fragrant” aroma? One clue is given to us in the book of Psalms, which describes the offering of incense as a visible symbol of the prayer of the Psalmist rising up to God:

I call upon you, O LORD; make haste to me! Give ear to my voice, when I call to thee!

Let my prayer be counted as incense before you, and the lifting up of my hands as an evening sacrifice!

(Psalm 141:1-2)

As we will see, just as the bronze altar of sacrifice prefigured the bloody sacrifice of Christ on Calvary, and the golden table of the Bread of the Presence prefigured the unbloody sacrifice of the Eucharist, so too the golden altar of incense prefigures the prayers of priest and faithful rising up to God in the Eucharistic sacrifice. In order to see this clearly, however, we will have to take a brief look at what Scripture and tradition reveal about the meaning and mystery of incense.

The Golden Altar of Incense

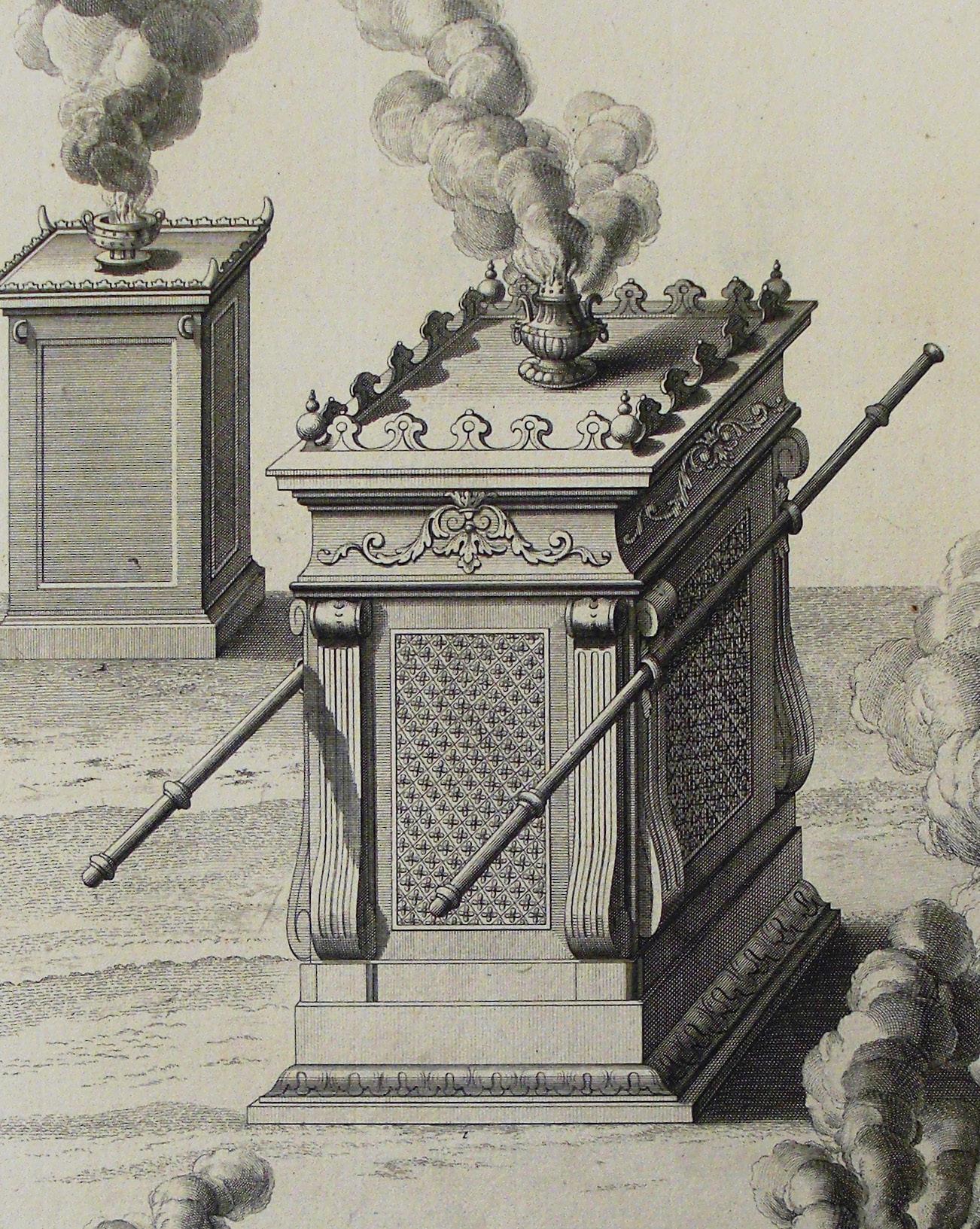

We begin by going back to the Old Testament roots of using incense in the liturgy.1 The foundational account of the golden altar of incense can be found in the divine instructions given by God to Moses for building the sanctuary known as the Tabernacle: “You shall make an altar to burn incense upon; of acacia wood shall you make it…. It shall be square, and two cubits shall be its height; its horns shall be of one piece with it. And you shall overlay it with pure gold…. And Aaron shall burn fragrant incense on it… a perpetual incense before the LORD throughout your generations. You shall offer no unholy incense thereon, nor burnt offering, nor cereal offering; and you shall pour no libation thereon… it is most holy to the LORD” (Exodus 30:1-3, 7-10). Notice here that by referring to this as an “altar” (Hebrew mizbeach), Jewish Scripture clearly implies that the burning of incense is a kind of sacrifice 2 Should there be any doubt about this, notice that the altar of incense is a square, with horns on the corners—almost identical to the bronze altar of animal sacrifice (cf. Exodus 27:1-8). However, several clues suggest that the altar of incense is even more sacred than the bronze altar. For one thing, the altar of incense is made of “pure gold,” like all the other sacred vessels in the Holy Place, as opposed to less sacred bronze vessels in the Outer Court. Moreover, the altar of incense is explicitly described as “most holy to the LORD.” Finally, it is not just any priest, but the high priest (Aaron) who has the duty of burning “fragrant

“The golden altar of incense prefigures the prayers of priest and faithful rising up to God in the Eucharistic sacrifice.”

With these words, the Psalmist begs God to accept his “prayer” as if it were “incense” and the raising of his hands—a familiar sacred gesture in ancient iconography and the Hebrew Scriptures—as if it were the evening “sacrifice” (cf. Psalm 55:18).3 Taken together, these expressions suggest that just as the smoke of the incense rises up to heaven, so too the prayers of the Psalmist rise up into God’s presence.4 From a biblical point of view, therefore, where there is the smoke of incense, there is the fire of prayer. And just as a sacrificial “offering by fire” is “a pleasing odor to the LORD” (Leviticus 1:9), so too “The prayer of the upright is his delight” (Proverbs 15:8).

Malachi’s Prophecy

Another reason incense is significant is because the Old Testament describes the future age of salvation as characterized by a surprising use of incense in worship. In the prophet Malachi’s rebuke of the corrupt priests in his day, the prophet declares that one day, incense will no longer be offered in only one place—the Jerusalem Temple—but everywhere—even among the Gentiles: “I have no pleasure in you [priests], says the LORD of hosts, and I will not accept an offering from your hands. For from the rising of the sun to its setting my name is great among the nations, and in every place incense is offered to my name, and a pure offering… says the LORD of hosts” (Malachi 1:1011).

It is difficult to overstate just how puzzling this oracle was for its original readers. For any ancient Jew would have known that according to the law of Moses, sacrifice could only be licitly offered in one place: the

Jerusalem Temple (compare Deuteronomy 12:10-14). Yet here is the prophet Malachi saying that not only will incense be offered to God “in every place,” but that a “pure offering” of bread (Hebrew minchah) will be offered “among the nations”—that is, the “Gentiles” (Hebrew goyim).5

Indeed, Malachi’s oracle would go on to become one of the most frequently cited Old Testament prophecies by the early Church Fathers, who saw its fulfillment in the Eucharistic sacrifice being offered among the Gentiles.6 In fact, in the Roman Missal of Paul VI, Malachi’s prophecy is quoted almost verbatim in Eucharistic Prayer III, when the priest prays: “You never cease to gather a people to yourself, so that from the rising of the sun to its setting, a pure sacrifice (Latin oblatio munda) may be offered to your name.”7 This is the exact same expression found in the Vulgate translation of Malachi’s oracle of a “pure sacrifice” (Latin oblatio munda) offered among the “Gentiles” (Latin gentibus) (Malachi 1:11, Latin Vulgate).

The Altar and Incense in Heaven

When we turn from the Old Testament to the New, we do not find explicit references to the use of incense in the early Christian liturgy. However, according to the

“The book of Revelation identifies ‘the smoke of the incense’ as ‘the prayers of the saints’—that is, those followers of Jesus still on earth— rising up from the hands of the angels to the throne of God.”

AB/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The original Tabernacle (or Tent) in the wilderness was constructed by Moses according to God’s design. The Altar of Incense— the third of the Temple’s altars—stood in the Holy Place along with the Golden Table of the Bread of the Presence.

Just as the Jewish priests on earth offer incense at the golden altar in the Temple, so too the angels in heaven offer “much incense” at the “golden altar” before God’s throne.

By referring to this as an “altar,” Jewish Scripture clearly implies that the burning of incense is a kind of sacrifice. The altar of incense is a square, with horns on the corners—almost identical to the bronze altar of animal sacrifice.

book of Revelation, the golden altar of incense in the Jerusalem Temple has a heavenly counterpart: “Another angel came and stood at the altar with a golden censer; and he was given much incense to mingle with the prayers of all the saints upon the golden altar before the throne; and the smoke of the incense rose with the prayers of the saints from the hand of the angel before God” (Revelation 8:3-4).

This is a truly stunning vision of the heavenly liturgy. Just as the Jewish priests on earth offer incense at the golden altar in the Temple, so too the angels in heaven offer “much incense” at the “golden altar” before God’s throne. And just as the book of Psalms describes incense as a symbol of prayer ascending to heaven (Psalm 141:2), so too the book of Revelation identifies “the smoke of the incense” as “the prayers of the saints”— that is, those followers of Jesus still on earth—rising up from the hands of the angels to the throne of God.8

Altar of Incense in Sacred Tradition

So much for sacred Scripture. What about the use of incense in the Church’s liturgical tradition? Though much could be said, three points stand out as worth highlighting.9 First, according to Origen of Alexandria, the smell of sacred incense reveals how God sees human prayer that is truly offered from the heart: “The type of incense symbolizes prayer…. This is the incense that God seeks to be offered by human beings to him, from which he receives a ‘pleasing odor,’ prayers from a pure heart and good conscience in which God truly receives a pleasing warmth” (Origen, Homilies on Leviticus 13.5.2).10

According to Origen, from a mystagogical point of view, incense is not just a visible sign of human prayer going up into heaven, but an odiferous sign of how much God delights in prayers that truly rise up from the depths of a pure human heart.

Second, according to St. Ambrose of Milan, the use of incense in the Eucharistic liturgy was also seen as a visible sign of the presence of the angels surrounding the altar: “It pleased God that we also, when we incense the altars, when we present the sacrifice, be assisted by the angel, or rather that the angel make himself visible. For you cannot doubt that the angel is there when Christ is there…” (Ambrose, Commentary on Luke 1.28).11

According to Ambrose, where there is the smoke of incense, not only is there the fire of prayer, but there too are the angels—the invisible spirits who bring God’s messages to us and our prayers to him.

Third and finally, in the Middle Ages, St. Thomas Aquinas tells us that incense was used both to increase the “reverence” (Latin reverentia) due to the Eucharist—in part by driving away bad smells!—and to make visible the invisible effects of Christ’s grace: “We use incense, not as commanded by a ceremonial precept of the Law, but as prescribed by the Church.... It has reference to two things: first, to the reverence due to this sacrament, i.e., in order by its good odor, to remove any disagreeable smell that may be about the place; secondly, it serves to show the effect of grace… from Christ

it spreads to the faithful by the work of His ministers, according to 2 Cor. 2:14: ‘He manifests the odor of his knowledge by us in every place;’ and therefore when the altar which represents Christ, has been incensed on every side, then all are incensed in their proper order” (Summa Theologiae III, q. 83, art. 5). What a beautiful combination of pragmatism and mysticism! Even to this day, in the Roman liturgy, after the offerings, the cross, and the altar are incensed by the priest, the deacon or acolyte incenses the priest and the people—thereby symbolizing the grace of Christ, which flows from the altar, through his priests and ministers, to the people.12

Mystery of Incense in Mass

With all of this biblical background in mind, we can bring this article to a close by asking: How does the ancient Jewish altar of incense shed light on the mystery of the Catholic altar today?

For one thing, it seems clear that the use of incense in the Catholic liturgy is not some puzzling anomaly or outdated medieval relic, but an ancient and venerable tradition that goes all the way back to the Old Testament. For this reason alone, we should strive to cultivate an appreciation for its use in the Mass today, especially in the dual incensation rites of the liturgy of the Word (the Book of the Gospels) and the liturgy of the Eucharist (the offerings, cross, altar, priest, ministers, and people).13 Making Catholics more familiar with the centrality of the golden altar of incense in ancient Jewish worship might go a long way toward helping them appreciate its role in the contemporary liturgy.

Moreover, as the New Testament reveals, the prayers of the saints on earth continue to rise up like incense before the heavenly altar of incense (Revelation 8:3).

According to the teaching of the Second Vatican Council, there is a correlation between the earthly and heavenly liturgies: “In the earthly liturgy we share in a foretaste of that heavenly liturgy… where Christ is sitting at the right hand of God…” (Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, no. 8). If the earthly Mass is a foretaste of the heavenly liturgy, then it is certainly fitting that we should use incense in the earthly celebration of the Eucharist. This would also help remind us that the liturgy is not just a rite or ritual, but, in its deepest mystery, the prayer of Christ and his Church. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the incensation of the altar itself during the liturgy of the Eucharist can be a powerful reminder that it is not just the altar of

“The use of incense in the Catholic liturgy is not some puzzling anomaly or outdated medieval relic, but an ancient and venerable tradition that goes all the way back to the Old Testament.”

sacrifice or the Bread of the Presence that is fulfilled in the Mass, but also the golden altar of incense. Consider the teaching of the Roman Missal itself on the biblical roots of incense in the liturgy: “The Priest may incense the gifts placed on the altar and then incense the cross and the altar itself, so as to signify the Church’s offering and prayer rising like incense in the sight of God…. Thurification or incensation is an expression of reverence and of prayer, as is signified in Sacred Scripture” (cf. Psalm 140 [141]:2; Revelation 8:3) (General Instruction of the Roman Missal, nos. 75, 276).

In these days when more and more Catholics—especially the young—are hungering for reverence in liturgy and deeper lives of prayer, these words of the Missal can provide a wonderful guide to help us better understand the splendor of sacred incense and the mystery of the Catholic altar.

To read Dr. Pitre’s other installments, On the Bronze Altar and The Golden Table, see the May and July 2025 print issues of Adoremus Bulletin.

Dr. Brant Pitre is Distinguished Research Professor of Scripture at the Augustine Institute, Graduate School of Theology. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Notre Dame, where he specialized in the study of Christianity and Judaism in Antiquity. He is the author of several books, including Jesus and the Last Supper (Eerdmans, 2015) and Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist (Doubleday, 2011). Dr. Pitre has also produced multiple video and audio Bible studies, including The Mass Readings Explained, an exposition of the three-year Roman Lectionary (available at BrantPitre.com). He and his family live in Louisiana.

1 See Kjeld Nielsen, “Incense,” Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman, vol. 3 (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 340–342.

2 See William H. C. Propp, Exodus 19–40, vol. 2A of Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 473, who notes the oddity: “Etymologically, mizbēach… should denote an altar for animal sacrifice.”

3 See Frank Lothar Hossfeld and Eric Zenger, Psalms 3: A Commentary on Psalms 101–150, trans. Linda M. Maloney, Hermeneia (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2011), 558.

4 Nielsen, “Incense,” 407: “The incense smoke carries the prayer to God.”

5 See Andrew E. Hill, Malachi, vol. 25D of Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 218: “The prophet’s avowal of the worship of YHWH among the nations in verse 11 remains a crux interpretum.” He sees it as a reference to “the future establishment of the kingship of God over all the earth.”

6 See Uwe Michael Lang, A Short History of the Roman Mass (Ignatius Press, 2024), 21-22, who cites Didache 14, Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho 41, and Irenaeus, Against Heresies IV.17-18 as examples.

7 Roman Missal, Order of Mass, no. 108 (Eucharistic Prayer III).

8 See Craig R. Koester, Revelation, vol. 38A of Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 379: “The term ‘saints’ or ‘holy ones’ (hagioi) was used for God’s people in Jewish tradition (Ps 34:10; Dan 7:21) and early Christianity (Acts 9:13)… Revelation uses it for the followers of Jesus (Rev 14:12; 17:6).”

9 For a full study, see Susan Ashbrook Harvey, Scenting Salvation: Ancient Christianity and the Olfactory Imagination (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006).

10 In Harvey, Scenting Salvation, 17.

11 In Lawrence J. Johnson, ed., Worship in the Early Church: An Anthology of Historical Sources, 4 vols. (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2009), 2:19.

12 See General Instruction of the Roman Missal, no. 178.

13 See General Instruction of the Roman Missal, no. 178, 276-77.

“The Priest may incense the gifts placed on the altar and then incense the cross and the altar itself, so as to signify the Church’s offering and prayer rising like incense in the sight of God…. Thurification or incensation is an expression of reverence and of prayer, as is signified in Sacred Scripture” (General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 75, 276).

AB/FR. JAMES BRADLEY ON FLICKR.

“Is Any Among You Sick?”—The Recipient of the Anointing of the Sick

By Owen Vyner

Most well-catechized Catholics can state with accuracy who can and should receive the sacraments with one sacrament as an exception. I often hear confusion regarding the Anointing of the Sick. In general, there are two extremes: the recipient is one for whom death is mere hours away, or the sacrament is to be given for any illness or surgery. I suspect that variations in the Church’s historical practice, coupled with a lack of sacramental catechesis explaining these changes, is largely responsible for the confusion.

“The Anointing of the Sick is a sacrament for those who begin to be in danger of death due to serious sickness or old age.”

To this end, we will present a brief overview of the history of the sacrament and the teachings of the contemporary Order of Anointing. As we will see, despite variations, the Church’s Magisterium has demonstrated consistency in its teaching. The Anointing of the Sick is a sacrament for those who begin to be in danger of death due to serious sickness or old age.

Development and Continuity

The question “Upon whom should the Anointing of the Sick be conferred?” is foundationally addressed in the Letter of St. James. We read in its fifth chapter: “Is any among you sick (asthenein)? Let him call for the elders of the Church, and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord; and the prayer of faith will save the sick (kamnonta) man, and the Lord will raise him up; and if he has committed sins, he will be forgiven” (5:14-15). The first Greek word designates a debilitating illness.1 In fact, within the context of the letter, the illness has immobilized the sick person such that the priests must come to him. The second Greek word has the meaning of “sickness beyond hope.”2 Thus, we are dealing with a person who is dangerously ill. Note too, there is a spiritual component to this danger, potentially necessitating the forgiveness of sins.

From the fourth century we find examples of prayers over the oil of the sick that continue this healing ministry for body and soul.3 By the end of the first millennium this concern for the gravely ill Christian who requires bodily and spiritual healing becomes increasingly expressed in the Church’s liturgical rites. In the ninth century, we witness the emergence of rich liturgies in Carolingian France and Germany. Additionally, these rites begin to link the Anointing of the Sick with the sacrament of Penance for those at the point of death.4 At this time, the sacramental ritual for those whose death is imminent follows this order: Penance, then Anoint-

ing, and finally Viaticum (reception of Holy Communion by the dying).5

During the next two centuries, pastoral and theological developments influence the question of the recipient of the sacrament. On a practical level, and for various reasons, the faithful began to postpone the sacrament of Anointing until the very end of life. Consequently, Anointing becomes a “sacrament of departure.” Also, during the scholastic period (12th to the 14th centuries) debate emerges regarding the sacrament’s effect. While both sides agreed that the sacrament was for those close to death, they disagreed on its purpose. In short, the Franciscans held that the main effect was the final remission of venial sin to prepare the Christian for entry into heavenly glory. The Dominicans, however, advocated that the principal effect was the removal of the remnants, or remains, of sin. This refers to the after-effects of original sin and personal sin that spiritually weaken the person, especially during times of serious illness or when facing death.6 As a result, at the end of the 12th century, under the influence of the Franciscans, the order of the last rites changes.7 The order of the sacraments for the dying became: Penance, Viaticum, and Extreme Unction.8 This will remain the order until Paul VI reformed the sacrament in 1972. We also see that, in the West, from the 12th century onwards the sacrament begins to be referred to exclusively by the name “Extreme Unction” (the final anointing).

The Council of Trent in 1551 provides the most comprehensive magisterial treatment of the sacrament up to this point. The debates surrounding the doctrine of the sacrament prove illuminating for the question of who receives. The first draft of the decree stated that the sacrament be administered “only to those who are in their final struggle and who have come to grips with death and who are about to go forth to the Lord.”9 Thus, the decree sought to enshrine the pastoral practice at that time of waiting until death is imminent.10 However, not all of the Council Fathers at Trent agreed with restricting the sacrament to those at the point of death. Among other reasons, these Fathers argued that the Letter of James referred to “the sick.” The final text established a middle path acknowledging that this was a sacrament for the seriously ill and for the dying. The Council of Trent thus decreed: “It is also declared that this anointing is to be applied to the sick, but especially to those who are in such danger as to appear to be at the end of life, whence it is also called the sacrament of the dying.”11

Hence, the recipient of the sacrament is especially one in danger of death, although not exclusively. And, as such, it may also be administered to those who are seriously sick. The final question that will need to be settled is whether this danger of death must be immediate or can it be remote? The 1614 Rituale Romanum used language such as “immediate danger of death” and restricted the administration to within “one day” of death. Nevertheless, as we will see, “danger of death”

will receive a broader subsequent interpretation from the Magisterium.

Twentieth-century Reform

Leading up to the 20th century, canonists began to interpret “danger of death” more broadly than “imminent death.” This finds confirmation in the 1917 Code of Canon Law that does not mention the “point of death” for administration; rather it states only “danger of death.” The relevant canon reads thus: “Extreme unction is not to be extended except to the faithful who, having obtained the use of reason, come into danger of death from infirmity or old age” (can. 940 §1).12 In fact, the Code encouraged priests to anoint while the infirm are still in full possession of their faculties (can. 944).

Two popes in the early 20th century both caution against waiting until the faithful are about to lose consciousness before anointing.13 Benedict XV and Pius XI taught that death need not be feared as immediate but only that there be prudent and probable danger of death.14

The teachings of the Second Vatican Council that ultimately operate as the principle of reform should be read in continuity with the doctrine of Trent and the magisterial teaching already mentioned. Sacrosanctum Concilium states: “‘Extreme unction,’ which may also and more fittingly be called ‘Anointing of the Sick,’ is not a sacrament for those only who are at the point of death. Hence, as soon as any one of the faithful begins

“Vatican II restored the original sequence for the three sacraments of the sick and dying: Penance, Anointing of the Sick, and the Eucharist as Viaticum.”

to be in danger of death from sickness or old age, the fitting time for him to receive this sacrament has certainly already arrived” (no. 73). Note that this teaching utilizes similar language to the 1917 Code of Canon Law although it added the phrase “begins to be in danger of death.” In turn, this will influence the 1983 Code of Canon Law. Its canon clearly builds upon Trent and the 1917 Code, while developing its language in light of recent magisterial teaching. The relevant canon in the Code states: “The anointing of the sick can be administered to a member of the faithful who, having reached the use of reason, begins to be in danger due to sickness or old age” (can. 1004 §1, emphasis added).

It should be noted that Vatican II restored the original sequence for the three sacraments of the sick and dying: Penance, Anointing of the Sick, and the Eucharist as Viaticum. It therefore returned the Eucharist to its proper place as the sacrament of those departing from this life. We see in this restoration a symmetry between the sacraments of Initiation that begin the Christian life and those at the end of our pilgrimage on earth. Both begin with a sacrament of conversion (Baptism and Penance); then follows an anointing sacrament (Confirmation and Anointing of the Sick); and both are completed by the Eucharist.

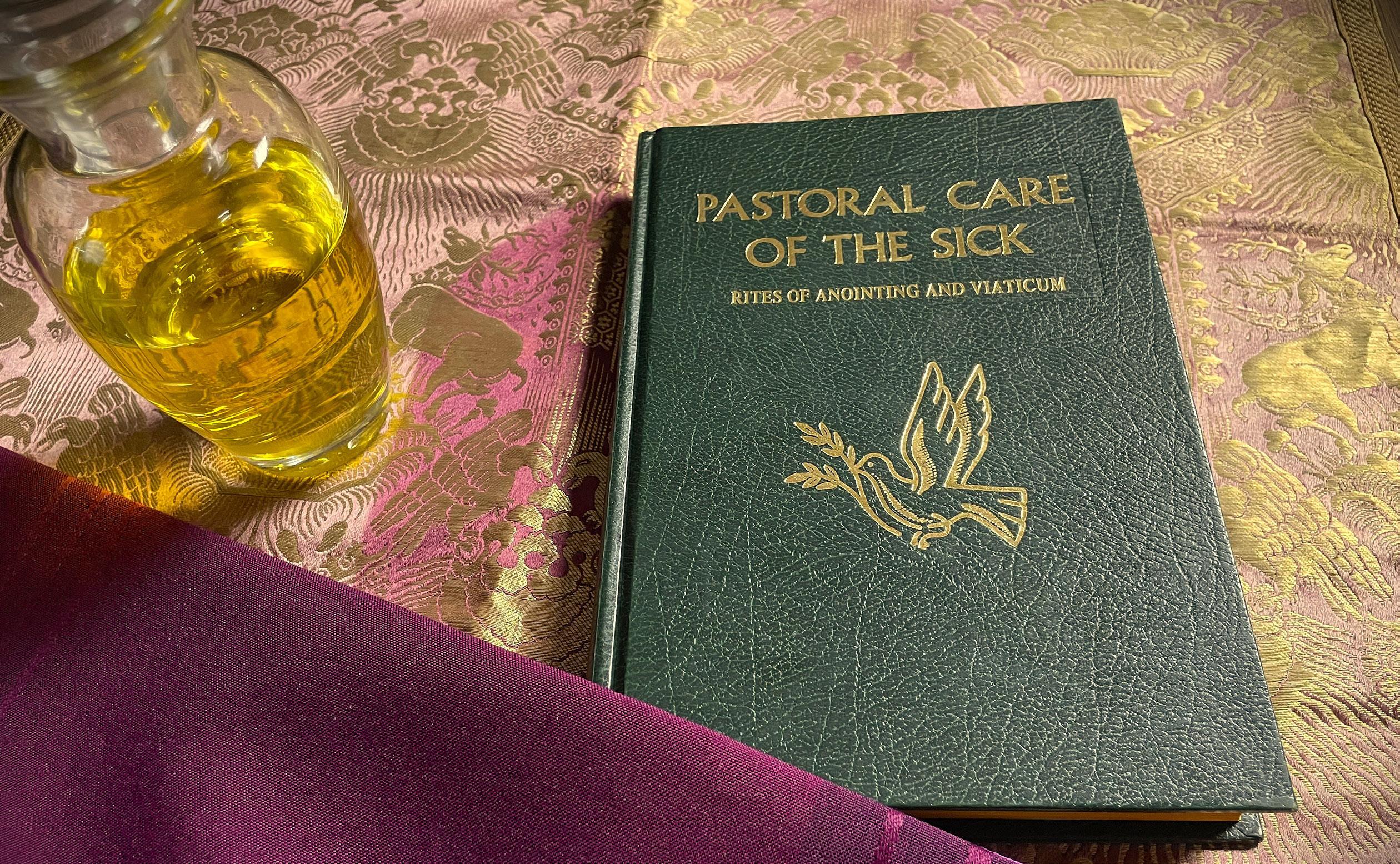

Revised Order of Anointing

The current approved ritual in the US is titled, Pastoral Care of the Sick: Rites of Anointing and Viaticum (1983). However, as of February 11, 2026, a new definitive English translation based upon the principles of Liturgiam Authenticam and which more closely follows the structure of the Latin typical edition will come into use. As the author has not seen the final approved text, we will rely on the Latin edi-

The current approved ritual in the US is titled, Pastoral Care of the Sick: Rites of Anointing and Viaticum (1983). However, as of February 11, 2026, a new definitive English translation based upon the principles of Liturgiam Authenticam and which more closely follows the structure of the Latin typical edition will come into use.

tion and provide its paragraph numbers for reference. The Latin edition is the Ordo Unctionis infirmorum eorumque pastoralis curae or the Order of the Anointing of the Sick and their Pastoral Care. At the time of writing, it is not certain which of the previous US adaptations have carried over into the new translation.

In its Introduction, or Praenotanda, the Ordo Unctionis provides a comprehensive overview of the recipient under the heading: “Those on Whom the Anointing of the Sick May Be Conferred.” What follows is a summary of the main points related to the Church’s teaching on the recipient of this sacrament.

Danger of death due to sickness or old age

The Anointing of the Sick is a sacrament intended to raise up and save the faithful who are seriously ill due to sickness or old age (no. 8). One notes a difference in language between Sacrosanctum Concilium that states “begins to be in danger of death” (periculo mortis) and the Introduction referring to those who are “seriously ill” (periculose aegrotat). Nevertheless, the key point is that we are dealing with a sickness that is serious enough that it places the Christian in danger. First, the danger must be due to sickness and not simply danger in itself (e.g., people who undertake perilous journeys are in danger but this is not due to illness). This will become important for questions pertaining to surgery. Second, if a priest is concerned as to whether a sickness

is grave, he should consult a doctor, but as long as there is a prudent judgment of probable danger, the priest can anoint. Third, the current US ritual warns that the sacrament should not be given indiscriminately or to those whose health is not seriously impaired.15 Regarding the communal celebration of the sacrament, the Code of Canon Law prescribes that the participants be “appropriately prepared and properly disposed ” (can. 1002). Such a prescription would surely exclude “healing liturgies” in which any of the faithful are invited to be anointed regardless of whether the illness is serious, or whether they have been properly prepared pastorally and catechetically. Finally, according to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Newsletter that announced the implementation date for the new English Order of Anointing, one of the US textual adaptations that has been retained is the permission to anoint those with serious mental illness. The condition for anointing a person with mental illness is twofold: a) the mental illness itself must be serious (a professional should be consulted if there is doubt) and b) the Christian would be strengthened by the anointing (PCS, no. 53).

When can the sacrament be repeated?

The sacrament may be repeated should the Christian recover and fall ill once again or, if in the same illness, a serious relapse occurs (no. 9). Thus, whether a Christian recovers and falls sick again, or if during the same illness the condition becomes more grave, the sacrament can be newly administered due to a worsening state of health.16 While the Anointing of the Sick does not impart an indelible character, the grace of the sacrament endures for the duration of the illness. In fact, some theologians maintain that Anointing bestows upon the recipient a “title” to grace from which the Christian may draw throughout the illness.17

Anointing and surgery

One may be anointed prior to surgery if a serious illness is the cause for the procedure. For example, while some people require general anesthetic to have their wisdom teeth removed, the removal of teeth would not be considered a serious illness; neither would a kneescope. Thus, while undergoing general anesthetic can be dangerous, it is not, in itself, reason to be anointed. Some priests have also anointed pregnant women prior to giving birth, yet this would imply that pregnancy is a serious illness. If a Christian is concerned that he could die (whether in surgery or travelling), the sacraments that he should receive are Penance and the Eucharist. The Anointing of the Sick is for the seriously sick and any danger must originate from the illness and not from external causes (no. 10).

The elderly

Those who have been greatly weakened through advanced age may also be anointed even when serious illness is not apparent (no. 11). The condition required is that the strength of the Christian be significantly diminished due to his age even if there is no suspicion of grave illness. One of the graces of this sacrament is to help persevere with the difficulties of old age (CCC, 1520). However, this does not mean that Christians should automatically be anointed once they reach a certain age.18

Children

Children who have attained the use of reason may be anointed (no. 12). This is due to the fact that one of the effects of the sacrament is the forgiveness of sin. If a dying person is unable to confess his sins (e.g., he is unconscious), Anointing of the Sick will forgive mortal sin, assuming that the person had an implicit desire to receive the sacrament.19 A child below the age of reason, however, is not considered capable of committing mortal sin. Therefore, should such a child face death or serious illness, he should receive Confirmation (can. 891) and, if possible, the Eucharist. In general, in danger of death, the faithful are canonically bound to receive holy Communion as Viaticum (can. 921 §1). In fact, this obligation is so important that the Code of Canon Law states that the faithful should receive Holy Communion daily while the danger of death lasts (can. 921 §3). If a

“While the Anointing of the Sick does not impart an indelible character, the grace of the sacrament endures for the duration of the illness.”

dying or seriously sick child can distinguish the body of Christ from ordinary food and receive communion reverently, he should receive Communion (can. 913 §2).

Those who have lost consciousness

If a Catholic has lost consciousness or the use of reason but it was known that he would have desired the Anointing of the Sick, he may receive the sacrament (no. 14). It is important that Christians who are seriously sick express their wish to be anointed to family and caregivers.

If the person has already died

If the person has already died when the priest arrives, the priest should not anoint. None of the Church’s sacraments may be administered to the dead as they are sacraments for the living.20 If it is known that the Christian has died, then the priest should beseech God to forgive the recently departed (no. 15). However, there are instances when death is not certain. Perhaps the person’s heart has stopped or he appears to no longer be breathing, yet it is not known if the soul has truly left the body. In these cases, and based upon the priest’s prudential judgment, he can anoint using a specific rite provided by the Ordo Unctionis (no. 135)

“It is important that Christians who are seriously sick express their wish to be anointed to family and caregivers.”

Those in obstinate and manifest grave sin

The Anointing of the Sick may not be conferred on those who obstinately persevere in manifest grave sin (no. 15). The Church has always excluded from her sacraments (especially the Eucharist), those who persistently remain in public sin (c.f. Matthew 16:19, 18:17-18; 1 Corinthians 5:4-6; 11:27-28). This prohibition serves a threefold purpose: 1) it calls the sinner to repentance through the Sacrament of Reconciliation; 2) it prevents the further spiritual harm of receiving a sacrament sacrilegiously; and 3) it prevents scandal of the faithful.

Opportunity for Encounter

As we have seen, from the beginning, Anointing of the Sick is a sacrament for the Christian who is seriously ill and in danger of death. It is not only for those at the point of death although neither is it to be given indiscriminately and for any illness. Rather, this is a sacrament that “commends those who are ill to the suffering and glorified Lord, that he may raise them up and save them” (CCC, no. 1499). It therefore becomes an opportunity for the seriously sick in danger of death and the aged to encounter the Lord and to be united to his death so as to rise with him.

Dr. Owen Vyner is Associate Professor of Theology and Chair of the Theology Department at Christendom College, Front Royal, VA.

1 John R. Donahue and Daniel J. Harrington, Sacra Pagina: The Gospel of Mark (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2002), 266-267.

2 Martin Dudley and Geoffrey Rowell, The Oil of Gladness: Anointing in the Christian Tradition (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1993), 58.

3 For example, see The Apostolic Tradition and Euchologion of Serapion

4 James Monti, A Sense of the Sacred: Roman Catholic Worship in the Middle Ages (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2013), 236.

5 This is seen in the Romano-Germanic Pontifical (950 A.D.), quoted in Monti, Sense of the Sacred, 237.

6 Thomas Aquinas, Sent IV, D. 23, Q. 1, A. 2, Response to Quaestiuncula 1.

7 Paul F. Palmer, “The Purpose of Anointing the Sick: A Reappraisal,” Theological Studies 19, no. 3 (1958): 343.

8 Palmer, “The Purpose of Anointing the Sick,” 343.

9 Palmer, “The Purpose of Anointing the Sick,” 336.

10 Charles George Renati, The Recipient of Extreme Unction (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1961), 31.

11 Council of Trent, Session 14, “Teaching Concerning the Most Holy Sacraments of Penance and Last Anointing, 25 November, 1551,” in Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils: Trent to Vatican II, ed. Norman P. Tanner, vol. 2 (London: Sheed & Ward, 1990), chap 3.

12 The 1917 or Pio-Benedictine Code of Canon Law: in English Translation, with Extensive Scholarly Apparatus, Edward N. Peters curator (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2001) (emphasis added).

13 John C. Kasza, Understanding Sacramental Healing: Anointing and Viaticum (Mundelein, IL: Hillenbrand Books, 2006), 65.

14 See Benedict XV, Sodalitatem Nostrae Dominae (1921); Pius XI, Explorata res (1923).

15 Pastoral Care of the Sick: Rites of Anointing and Viaticum Approved for Use in the Dioceses of the United States of America (Totowa, NJ: Catholic Book Publishing, 1983), 21n8.

16 Bronislaw Wenanty Zubert, “Title V: The Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick,” in Exegetical Commentary on the Code of Canon Law, Prepared under the Responsibility of the Martín de Azpilcueta Institute, Faculty of Canon Law, University of Navarre, Volume III/1, English edition ed. Ernest Caparros (Chicago, IL: Midwest Theological Forum, 2004), 888.

17 Joseph A. De Aldama, et al., Sacrae Theologiae Summa IVA On the Sacraments in General: On Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Penance and Anointing, trans. Kenneth Baker (Ramsey, NJ: Keep the Faith, 2015), 613.

18 Zubert, “Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick,” 886.

19 CCC, no. 1532. See also Colman O’Neill, Meeting Christ in the Sacraments (Revised Edition) (Staten Island, NY: St Pauls, 2019), 287-288.

20 Zubert, “Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick,” 890.

The sacred oils are kept in the church’s ambry. The oil of the sick is used to anoint those who begin to be in danger of death due to serious sickness or old age.

“Is any among you sick? Let him call for the elders of the Church, and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord; and the prayer of faith will save the sick man, and the Lord will raise him up; and if he has committed sins, he will be forgiven” (James 5:14-15).

AB/LAWRENCE OP ON FLICKR. FRA ANGELICO ALTARPIECE FOR THE CHURCH OF SAN DOMENICO.

“Over the course of time, the lives of the Saints shine forth as a continuation of the memory of the life of Christ, demonstrating the glory of his resurrection in this world, and are presented to the Christian faithful as stars with greater intensity, in that while ‘all things pass away, the glory of the Saints endures’” (Martyrologium Romanum, 10).

onstrating the glory of his resurrection in this world, and are presented to the Christian faithful as stars with greater intensity, in that while ‘all things pass away, the glory of the Saints endures.’”2 The Collect continues by affirming the central role of the saints as intercessors, leading and encouraging our reconciliation in Christ (see Ephesians 1:10).

The Prayer Over the Offerings during Mass speaks of the saints being “already assured of immortality.”3 The Roman Martyrology again confirms that the saints “are more intimately united with Christ.” In their in-

“The saints take the experience of worship to a heightened pitch, contributing to the entire Church in one voice of praise to God.”

timacy and union with Christ, they “witness to the holiness of the Church” while also “ennobling the worship which the Church offers to God, contributing to its edification.”4 The immortality that the saints enjoy is their own participation in the merits of Jesus’ resurrection, Christ being the “first fruit” of this mystery (1 Corinthians 15:20-23). The saints, in turn, take the experience of worship to a heightened pitch, contributing to the entire Church in one voice of praise to God.

Towards a Heavenly Homeland

The Preface of the Mass for the Solemnity of All Saints is proper to the solemnity, and it speaks of our “celebrating the festival of the city, the heavenly Jerusalem, our mother.”5 In this moment, the Church is directing our attention to heaven, situating our celebration of the saints in the larger experience and hope of heaven, our true home. This resonates with Pope Benedict XVI in his encyclical Spe Salvi: “To imagine ourselves outside the temporality that imprisons us and to anticipate the joy of eternal life... this is not a mere dream or illusion.”6 This expectation of heaven is echoed again in the Prayer after Communion, relating our reception of Holy Communion to the hope for heaven: “coming to per-

“The Mass itself is a participation in our heavenly hope, already experienced in its fullness by the saints in heaven.”

fect holiness in the fullness of your love, we may pass from this pilgrim table to the banquet of our heavenly homeland.”7 The Mass itself is a participation in our heavenly hope, already experienced in its fullness by the saints in heaven.

Saints in the Roman Canon

The experience of the saints in the Catholic Mass is plentiful. One has only to recall the variety of saints that make up the General Roman Calendar. Additionally, many religious congregations and national episcopal conferences or dioceses add religious or regional saints to their particular calendars. Beyond the calendar, mentions of the saints appear throughout the liturgy, with the Blessed Virgin Mary receiving particular prominence. A curious and unique list of saints that enjoy pride of place in the Mass, however, are those saints in

the Roman Canon, or Eucharistic Prayer I. What is the significance of these saints, and why are they included in the official prayer of the Church?

A hallmark of the Roman Canon is the inclusion of the saints in the Communicantes and the Nobis Quoque Peccatoribus. Beginning with the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Communicantes, the Church ascribes to her certain prerogatives: glorious, ever virgin, and mother of God.8 In the hierarchy of the saints, the Blessed Virgin Mary rightly occupies pride of place. The text moves on to St. Joseph, the universal patron of the Church. Although his inclusion is a later addition to the text of the Roman Canon under Pope Saint John XXIII, devotion to St. Joseph is witnessed to in other prayers of the Mass. The apostles are named immediately after the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Joseph, beginning with Peter and Paul. These apostolic witnesses, with the exception of St. Paul, sat with the Lord at the Last Supper when our Lord instituted the Eucharist. The list turns to 12 other saints, martyrs, and early popes, all of Roman pedigree. This list mirrors that of the apostles, and witnesses to the particularly Roman character of the Canon. Only martyr-saints appear in the Canon since devotion to saint-confessors was not as well established in the early Church. The number 12 is particularly significant, since it represents perfection and the universality of the Church.9

Beginning with the Nobis Quoque Peccatoribus, the Canon points to 15 other saints, already venerated in Rome where churches in their honor had arisen. The Church desires to relate their witness to the “Holy Apostles and Martyrs” mentioned earlier in the text.10 Notable saints in this list include John the Baptist, Stephen, Matthias, and Felicity and Perpetua. Catholics should become familiar with these early witnesses. Saints like Anastasia, for example, are perhaps not as well known but are part of our larger Church. Martyred in the year 304 under the emperor Diocletian, she suffered under her pagan husband for being completely dedicated to works of charity. According to tradition, the popes of the early Church would celebrate the second Mass of Christmas in the church built over the ruins of her home with her feast day also celebrated on December 25.11

Litany of the Saints: A Brief History

Litanies are common in the devotional life of Catholics. Many Catholics are familiar with a variety of litanies meant to deepen appreciation among the faithful for Christ and his mysteries: litanies of the Blessed Virgin Mary, of the Holy Name, of St. Joseph, and for the Dying. The most venerable and easily recognizable litany in our tradition, however, is the Litany of the Saints. This hauntingly beautiful prayer—experienced in the context of many rituals—enjoys a particular pride of place in our lives as Catholics.

Litanies are “a form of prayer consisting of a series of petitions or bidding prayers which are sung or said by a deacon, a priest, or cantors, and to which the people make fixed responses.”12 We find instances of litanies in the experience of Israel and the Old Testament, specifically in the Psalms. Litanies have been carried over into the practice of Christianity and are experienced by Catholics on most Sundays in the Kyrie of the Mass. The experiences of litanies in the Christian East are plentiful, with the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom launching almost at once into the Litany of Peace, also called The Great Litany In the context of Christian liturgy, litanies assume the conscious and active participation of the faithful, drawing them into a deeper experience of the mysteries.

The advent of Christianity and devotion to the saints are almost synonymous. Early Christian hagiographies such as the Martyrdom of Polycarp (155 A.D.) and the later biographies of St. Martin of Tours and St. Benedict, give witness to early Christian devotion to the saints. There exists evidence that an early form of the Litany of the Saints existed in Asia Minor by the third or fourth century. It likely developed later in the Christian West, with evidence of its existence in England and Ireland by the eighth and ninth centuries, respectively. The primitive Litany of the Saints was likely combined with other litanies then in use, one marked by invocations to Christ, and the other marked by the response Te rogamus, audi nos (“We ask you, hear us”) 13 It was this meeting of litanies that provided the form of what we know today at the Litany of the Saints.

Many invocations of individual saints and other invocations eventually crept into the litany, leading Pope

“In the context of Christian liturgy, litanies assume the conscious and active participation of the faithful, drawing them into a deeper experience of the mysteries.”

Clement VIII in 1601 to determine the official text of the litany while prohibiting the public use of other litanies unless approved by Rome. In 1969, the Litany of the Saints was updated with the addition of modern saints. The revised version also allows for the addition of the names of other appropriate saints as well as further petitions that may be suitable for a particular occasion.14

Litany of the Saints Today

Today, the Litany of the Saints finds a home in a number of the Church’s rituals: the celebration of baptism at the Easter Vigil in the Order of Christian Initiation of Adults, the Order of Baptism for Children, the Commendation of the Dying, the Order of Ordination of Deacons, Priests, and Bishops, the Rite of Consecration to a Life of Virginity, the Rite of Perpetual Profession of Religious Women and Men, the Blessing of Abbots and Abbesses, the Dedication of a Church and an Altar, and on the First Sunday of Lent.15

It is significant that the Litany of the Saints finds a frequent home in rituals and experiences of vocation: either the universal vocation of holiness initiated by baptism and finding its completion in death, or the particular vocations experienced in Holy Orders or Religious Consecration. The beginnings of discipleship, initiated at baptism and accompanied by the saints’ intercession, are confirmed and elevated in the particular vocation of Holy Orders or Religious Consecration with the parallel invocation of the saints in this venerable litany. The conspicuous absence of the Litany of the Saints in the recently revised Order of Celebrating Matrimony, therefore, does seem like a missed opportunity to draw similar connections between baptism and the vocation of marriage.16

Witnesses Now and Forever

In the rhythm of the Mass, the saints are not distant historical figures but living witnesses who accompany the Church in her worship. Through the reverent mentions in the Roman Canon and the solemn invocations of the Litany of the Saints, we are reminded that the saints are intimately united with us in the mystery of the liturgy. In honoring the saints, we are drawn deeper into the heart of the Church’s worship, where time and eternity meet, and where we are called to join their eternal song of praise as members of the Body of Christ.

Father Ryan Rojo is a priest of the Diocese of San Angelo, TX, currently serving as Vocation Director and Director of Seminarians. He attended Mundelein Seminary in the Archdiocese of Chicago and was ordained to the priesthood on May 30, 2015. Following ordination, he returned to Mundelein to complete a Licentiate in Sacred Theology (STL) at the Liturgical Institute. Father Rojo has served as Parochial Vicar at Sacred Heart Cathedral in San Angelo and at St. Ann’s Parish in Midland. He later earned a Master of Science in Church Management from Villanova University, Philadelphia, PA. He is a member of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre and was recently selected as one of 50 preachers for the National Eucharistic Revival, speaking at parish missions across the country.

1 Roman Missal: Altar Edition, 3rd ed. (Mahwah, NJ: Magnificat, 2021), 973.

2 Martyrologium Romanum (Vatican City: Typis Vaticanis, 2001), 10. My Translation.

3 Roman Missal, 973.

4 Roman Missal, 973.

5 Roman Missal, 973.

6 Benedict XVI, Spe Salvi: Encyclical Letter on Christian Hope (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2007), 12-13.

7 Roman Missal, 973.

8 Amleto Giovanni Cicognani, The Saints Who Pray with Us in the Mass (Kansas City, MO: Romanitas Press, 2017), 16.

9 Cicognani, The Saints Who Pray with Us in the Mass, 16.

10 Cicognani, The Saints Who Pray with Us in the Mass, 26.

11 Cicognani, The Saints Who Pray with Us in the Mass, 30.

12 F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, eds., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1974), s.v. “Litany,” by N. Serarius, S.J.

13 Michael D. Whelan, “The Litany of Saints—Its Place in the Grammar of Liturgy,” Worship 65, no. 3 (1991): 216–223.

14 Ann Ball, A Litany of Saints (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 1993), 25.

15 Donald G. LaSalle Jr., “The Litany of the Saints: Practicing Communion with the Holy Ones,” Liturgical Ministry 12, no. 1 (Winter 2003): 20-29; and Paschale Solemnitatis, 23.

16 The USCCB sought a proposed adaptation to include the Litany of the Saints in the revised Order of Celebrating Matrimony as an option following the homily. The Congregation for Divine Worship and Discipline of the Sacraments acknowledged the good intentions which motivated the request, but remarked that such a litany “must be seen as out of harmony with the structure of the marriage celebration through the centuries.” See: USCCB Committee on Divine Worship, Newsletter, July 2015.

: What is a convalidation?

A: A convalidation is an exchange of valid marital consent between parties, at least one of whom is Catholic, who are not married, but had previously attempted to marry.

Q: Why is it sometimes called “blessing a marriage?”

A: A convalidation is not a blessing of an existing marriage. This is a very frequent misunderstanding. For a convalidation to be necessary, the couple must have tried to marry previously but not actually formed a valid marriage bond.

It may be that convalidations are referred to as “blessings” because this avoids the topic of why the convalidation is required: there was not a valid marriage. It is easier, though incorrect, to ask a couple if they want to have their marriage blessed than it is to ask a couple if they would like to make their invalid marriage valid. The significant difference between a wedding and a convalidation is that in the case of a convalidation, there was already an attempt by the couple to marry. A wedding and a convalidation are similar, however, in that in both situations the parties were not married before the event, and are married afterwards.

Q : What does it mean for a marriage to be valid or invalid?

A: An invalid marriage is one that lacks something which it would require to become all a marriage should be. The validity of a marriage is established when the two parties exchange consent and the bond of marriage is formed between them. If the consent they exchange is inadequate to form the bond or is prevented from forming the bond, they would have an invalid marriage. All marriages are presumed to be valid until proven otherwise, even if the couple has civilly divorced.

Q : What could make a marriage invalid?

A: There are three ways a marriage can be invalid: A marriage could be invalid because consent was exchanged while either party was personally prevented from entering marriage. In canon law, we call this person “impeded.” There are impediments of both divine origin, to which all are subject, such as already being married. There are also impediments of ecclesiastical origin, to which Catholics are subject, such as Catholics only being able to marry other baptized Christians. Since the latter is of ecclesiastical origin, it can be dispensed by ecclesiastical authority, which is why a bishop or someone he has appointed may allow Catholics to marry unbaptized partners. The different impediments are found in canons 1083-1094 of the Code of Canon Law. A person is impeded if he or she is: under a certain age; perpetually and antecedently unable to perform the marital act; bound to a prior marriage; a baptized Catholic marrying someone who is not baptized; ordained; bound by a public perpetual vow of chastity in a religious institute; kidnapped with marriage as the goal; the killer of either their own spouse or their intended partner’s spouse with marriage as the goal; are closely related by blood; very closely related by marriage; very closely related by a relationship that resembles marriage; very closely related by reason of adoption.

A marriage could be invalid because at least one of the parties exchanged defective consent. To form a marriage, a man and a woman must consent to a union that is fruitful, faithful, and permanent. Canonically speaking, their consent must not positively exclude anything essential to marriage, it must be formed by an adequately functional intellect and will, it must be given freely, and each of the consenting parties must be able to function as a spouse. Marital consent may be lacking for the reasons described in canons 1095-1105. The thorough discussion of how exactly a person might be unable to give the appropriate marital consent could fill (and has filled) many books, but a few simple examples of defective consent are: lacking the ability to reason, intending