The Liturgical Legacy of Pope Benedict XVI

Catholics and Orthodox to Celebrate Easter on the Same Date?

By AC WimmerCNA—In a move that could lead to Catholics and Orthodox celebrating the Resurrection of Jesus Christ at the same time, the spiritual leader of the world’s Eastern Orthodox Christians has confirmed his support for finding a common date to celebrate Easter.

Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople told media that conversations are underway between Church representatives to come to an agreement, Zenit reported in November.

According to an earlier report by Vatican News, the patriarch supports such a common date to be set for the year 2025, which will mark the 1,700th anniversary of the First Ecumenical Council of Nicea. Previously, Orthodox Archbishop Job Getcha of Telmessos also suggested that 2025 would be a good year to introduce a reform of the calendar.

The First Council of Nicea, held in 325, decided that Easter would be celebrated on the first Sunday after the full moon following the beginning of spring, making the earliest possible date for Easter March 22 and the latest possible April 25.

Today, Orthodox Christians use the Julian calendar to calculate the Easter date instead of the Gregorian calendar, which was introduced in 1582 and is used by most of the world. The Julian calendar calculates a slightly longer year and is currently 13 days behind the Gregorian calendar.

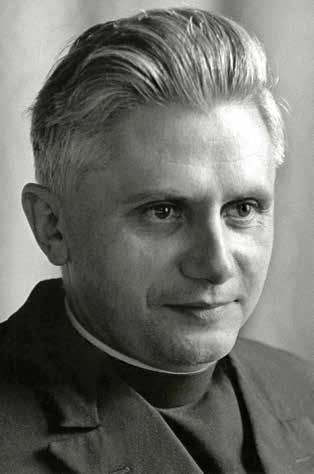

By Father Uwe Michael LangIt is no easy task to render justice to the liturgical legacy of Benedict XVI, whose pontificate stands out in so many ways, and I accepted Adoremus Bulletin’s request with mixed sentiments of gratitude and trepidation. In the first place, I am truly grateful for Benedict’s momentous contributions to the liturgical life of the Church, as a scholar and theologian, as well as a pope and pastor of souls. At the same time, I cannot deny a sense of apprehension, as I set out to consider the lasting impact of a pope who had to fight so many painful battles within the Church and whose renunciation from the Petrine office in 2013 appears to have called into question so much of his achievement. Having had the grace and honor to know the late Joseph Ratzinger personally, I find it incomprehensible how a man of such gentleness, humility, and openness in listening to others was often met with anticipated hostility from outside, and with thinly veiled obstruction from inside the Catholic Church. And yet, I am convinced that his epochal labors to restore the sacred liturgy to the heart of the Church, with

intellectual courage, spiritual depth, and at great personal cost, have only begun to bear fruit and will prove his lasting legacy to Christianity.

that seemed expedient in the given circumstances; rather, it reflected the right ordering of the Church’s life and mission:

“God First”

As Joseph Ratzinger noted in his autobiography, the Church’s worship had shaped his faith and his life from his childhood.1 Although his academic career focused on dogmatic and fundamental theology, Ratzinger considered the theology of the liturgy central to his work as a priest and scholar. In the preface to Theology of the Liturgy, the 11th volume of his collected writings (which was the first one to be published, at his express wish, in 2008), Benedict XVI drew attention to the fact that the Council’s first document was the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium. In his view, this was not just a pragmatic decision

The Liturgical Pope: RIP

Many a pope has made a lasting mark on the Church—and Father Uwe Michael Lang maintains that the late Pope Benedict has made his in deepening our understanding of and love for the liturgy 1

Facetime with Jesus What do you do during Adoration anyway? According to Father Justin Kizewski, a lot. But most importantly, you gaze at Jesus and he gazes back, helping you to deepen your Eucharistic love 6

Sunday > Saturday

In fact, since Sunday is greater than any other day of the week, John Grondelski says Saturday

“Beginning with the liturgy tells us: ‘God first.’ When the focus on God is not decisive, everything else loses its orientation. The saying from the Rule of St. Benedict ‘Nothing is to be preferred to the liturgy’ (43,3) applies specifically to monasticism, but as a way of ordering priorities it is true also for the life of the Church and of every individual, for each in his own way.”2

Pope Benedict then recalled a theme he has widely explored in his writing and preaching—the fullness of meaning of “orthodoxy”: “It may be useful here to recall that in the word ‘orthodoxy,’ the second half, ‘-doxa,’ does not mean ‘idea,’ but, rather, ‘glory’ (Herrlichkeit): it is not a matter of the right ‘idea’ about God; rather, it is a matter of the right way of glorifying him, of responding to him. For that is the fundamental question of the man who begins to understand himself correctly: How must I encounter God? Thus learning the right way of worship-

Night Sunday Mass may be doing more harm than good in efforts to keep holy the Sabbath Day 7

Which Came First…?

Genesis or Exodus? Well, both, says Matthew Tsakanikas, who sees Moses packing the Creation story with liturgical wisdom he picked up on the road from Egypt to the Promised Land 9

“Beginning with the liturgy tells us: ‘God first.’ When the focus on God is not decisive, everything else loses its orientation.”Pope Benedict XVI taught us to ask life’s decisive question: “How must I encounter God? Learning the right way of worshiping—orthodoxy—is the gift par excellence that is given to us by the faith.” Thank you, Pope Benedict, for your liturgical leadership and holy example!

The president of the Pontifical Council for Christian Unity, Cardinal Kurt Koch, has supported the suggestion that Catholics and Orthodox work to agree on a common date to celebrate Easter.

Cardinal Koch said in 2021: “I welcome the move by Archbishop Job of Telmessos” and “I hope that it will meet with a positive response.”

“It will not be easy to agree on a common Easter date, but it is worth working for it,” he stated. “This wish is also very dear to Pope Francis and also to the Coptic Pope Tawadros.”

One possible obstacle to a universal agreement could be ongoing tensions between different churches. In 2018, the Russian Orthodox Church severed ties to the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople after Patriarch Bartholomew confirmed that he intended to recognize the independence of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine.

Cardinal Robert Sarah Pens Guide to the Spiritual Life

By Andreas ThonhauserEditor’s Note: During a November 7 interview in Rome, Cardinal Robert Sarah, former prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and Discipline of the Sacraments, spoke about his latest book, Catechism of the Spiritual Life, published by EWTN Publishing in October 2022. The oncamera interview was conducted by EWTN Rome Bureau Chief, Andreas Thonhauser. Minor editing changes were made for clarity. Adoremus has also edited the interview for length.

Your Eminence, what made you decide to write a book on the spiritual life?

Amidst the confusion of this day, outside and even inside the Church, I saw a need for a representation of some reflections on our spiritual progress in our spiritual life: progress in our personal and intimate relationship with Jesus Christ. It is not a catechism to compete with the Catechism of the Catholic Church, but it is narrower in scope, I hope answering a profound need of our time. Every one of us must strive, continuously, to draw closer to Jesus Christ, to return to his word, and to the simplicity of the faith in his self-revelation. It is the simplicity of the desert, of recognition of our dependence upon God, and encountering him and the gift of his love and his grace, by which he configured us to himself. That is why I decided to write Catechism of the Spiritual Life.

And why would you say the spiritual life needs a catechism?

Well, God has been forgotten in modern society. We all live as if God doesn’t exist. Confusion reigns everywhere. Too many would reduce our lives, the very meaning of our lives, to absolute individualism and the pursuit of fleeting pleasure. In this situation, then, we require a retreat from the world, withdrawal into the desert, where we can relearn the fundamentals, the basics: monotheism, the revelation of Jesus Christ, us and God, his word, our sin, our dependence and need of his mercy. Through his Church and the sacraments, God guides us into an ever-deeper relationship with him. And we all have a need to reacquaint ourselves with his profound gift, which is his love. So we need a catechism because we need to approach [closer and closer] to God.

How does one enter, and how does one progress in, the spiritual life? And how does this path differ from a nonspiritual life?

We enter into spiritual life by following Christ. He turns us toward himself, by his grace. We are led by him. And like the Hebrews, he leads us into the desert. There is a characteristic of spiritual life: There is no illusion of selfsufficiency, no false sense of security. We are justified only by Christ; we depend on him. He is our rock, and the Word of God is our firm foundation. This is another characteristic of spiritual life. Worldly life is built on sand. Without God’s word, people can think that they live an upright life, but it is illusory. The principles and values of moral law meet and find their reconciliation only in Christ. Human reason requires God’s help. Without God, we cannot live any just life, any vital life. We need God.

You describe the sacraments as pillars of the spiritual life. Do you think we need to put more effort into explaining the sacraments as the pillars of spiritual life and bring them to the attention of our modern society?

VIEWS

Sure. The sacraments remain part of the life of the faithful. But their significance has been forgotten or obscured by worldly concerns. We need to rediscover this as the principal means of grace that Jesus established in his Church. We need to understand the sacraments. They are not social affairs. Baptism, for example, should not be delayed to wait for a family gathering. But parents must hasten to baptize the children because their baptism is really the gate to the spiritual life, the gate to enter into the Church. Each of the seven sacraments is a gift of the Church, to illuminate how God intervenes in our lives for the sake of our salvation. So we need to explain more deeply: What is baptism? What is confirmation? What is the Eucharist? Not only a meeting for families. So this is why I wrote this book: to deepen our knowledge of the sacraments.

But you also write about the loss of faith in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Why do you see this loss of faith as a cause for a decline of Christian communities? And how could we revive this faith?

I know that without faith in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the Church becomes only a horizontal phenomenon. The Church loses the meaning of her existence. The Church is not a social organization, to meet the problems of migration or poverty. The Church has a divine purpose: to save the world. If Christ does not dwell within the Church, tangibly, visibly, sacramentally, then what good news do we have to offer to the world? What is the meaning of evangelization? When Christians forget why they are Christian, the community must fall into decline. They forget the Gospel and lose sight of their purpose.

For those who still approach the Eucharist, if they lack faith in the Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist, they will likely receive him, but unworthily, so without the result of progress in the Christian life. They, thereby, do violence to his Body, bringing condemnation upon themselves, and further hastening the community decline. To restore the Church, we need only to listen to the words of Jesus Christ: “This is my Body; this is my Blood.” Christ is not merely present in thought, subjectively. When you gather for the Holy Mass, he is present to us in the most supreme manner: In his Body, in his Blood, in his Soul, in his Divinity. In the Eucharist, he gives himself to us as food. He enters into our bodies, and he does not disappear in us, but we are taken up to him. We dwell in him, and he dwells in us. So beautiful is the Holy Mass, that if, only for a moment, we quiet ourselves and consider the immensity of the Eucharist, our faith in his presence must spring into life and lift our hearts to him.

Perhaps we can stay on this subject: the sacredness of the liturgy. Can you tell us more about its sacredness? What role does, for example, silent adoration in front of the Eucharist play? How do we lead people back to the mystery of adoration and to the appreciation of the adoration?

In the Eucharist, we encounter Jesus Christ, personally and intimately. Holy Mass is an essential part of Christian life. Christ himself tells us, “Do this in memory of me.” But having encountered him in the liturgy, how can we not desire to spend time with him in silent adoration? The minutes and the hours that we spend in his presence in the Eucharist continue his work in us by which he transforms us and conforms us to himself, makes us so that we become Christ, himself. The liturgy is sacred. It is our responsibility to confirm ourselves to eat, to be shaped by the liturgy, to reflect its holiness. The liturgy is sacred, it is holy, because it comes from God. It is not our invention, our creation.

And when we encounter Christ in the Eucharist, silently, we really change our lives. We really become his disciples; we really become Christian. This is quite clear from this

Adoremus Bulletin

Society for the Renewal of the Sacred Liturgy

PHONE: 608.521.0385 WEBSITE: www.adoremus.org

MEMBERSHIP REQUESTS & CHANGE OF ADDRESS: info@adoremus.org

reflection upon what we are doing in the liturgy: We commemorate the death and the resurrection of Our Lord by which he redeems us and draws us into his divine life. The liturgy leads us to his divine life. And I will encourage us to keep the liturgy more and more sacred, more and more holy, more and more silent, because God is silent, and we encounter God in silence, in adoration. I think that the formation of the people of God in the liturgy is very important. We can show people the beauty, to be reverent, and to keep silent in the liturgy, in which our encounter with Christ is deepened.

During my time as prefect of the sacred liturgy [congregation], I learned that liturgy must be a very great moment, a very unique moment, to encounter God faceto-face and to be transformed by him as a child of God and as a true worshipper of God. Liturgy must be beautiful, it must be sacred, and it must be silent.

I think that we must be more careful, when we are gathered for the Eucharist at Mass, not to transform the sacred Mass into a spectacle or a drama, or a phenomenon of gathering people together because they are friends, but, rather, to worship God. And when we worship God silently, then God will transform our lives. We become like God.

St. Irenaeus said, “God has made man that man becomes God.” And the liturgy contributes to make us God. It is very important to really progress in sacred liturgy: not to let people create their own liturgy and desecrate the liturgy, but to make it more powerful as the presence of God among men.

You also mentioned in your book that the ultimate weapon in the spiritual battle is penance. But we see that many refuse or ignore the gift of confession. What is your explanation for this?

Well, confession appears at the very beginning of the Gospel. Jesus said to us: “Repent, for the kingdom of God is at hand.” At the beginning, Christ commanded [all people] to confess, to repent. Repentance is the beginning of divine life, the restoration of our friendship with God. The sacrament of confession is a wonderful gift by which God, again and again, restores us in his grace. We ought to welcome in our hearts sorrow for our sins, which is the work of the Holy Spirit, and receive the liberty from sin that comes with repentance. We ought to make a habit of this, turning, again and again, day after day, to the Lord, escaping, quickly, the despair, the deception of this world.

Rather than embracing the gift of confession, too many have come to resent it. In doing this, they resent the truth: That is the truth, that they are a sinner in need of God’s mercy. Unfortunately, we have lost, in recent decades, the sense of sin. Many do not accept that man is a sinner. There is no sin today.

Perhaps some of the faithful resent confession because they cannot submit to the authority of priests. So many of those whose reputations are ruined by the atrocity of sexual abuse committed by a few priests. But these rebellions are mistaken because confession has nothing to do with a personal worthiness of the priest. The priest can be a sinner. But through the priest, it is Christ who forgives. So we do not have to look at the priest who is a sinner. Through the priest, it is Christ who forgives. We all require his forgiveness. And he would pass through the priests.

And no mistrust or resentment of the priest should stop us from going to confession. We know that St. Augustine said, when priests baptize, it is Christ who baptizes. When Judas baptized, it was Christ who baptized. If a sinner baptizes in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Spirit, it is Christ who baptizes. So it doesn’t matter that the priest is insufficient. We have to go to him and recognize our sins, and God will forgive us.

Editor’s note: To read the full interview, see https://www. ncregister.com/interview/cardinal-robert-sarah-pens-aguide-to-the-spiritual-life.

EDITOR - PUBLISHER: Christopher Carstens

MANAGING EDITOR: Joseph O’Brien

CONTENT MANAGER: Jeremy Priest

GRAPHIC DESIGNER: Danelle Bjornson

OFFICE MANAGER: Elizabeth Gallagher

MARKETING AND FUNDRAISING: Eugene Diamond

SOCIAL MEDIA: Jesse Weiler

INQUIRIES TO THE EDITOR P.O. Box 385 La Crosse, WI 54602-0385 editor@adoremus.org

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE

The Rev. Jerry Pokorsky = Helen Hull Hitchcock

The Rev. Joseph Fessio, SJ

Contents copyright © 2022 by ADOREMUS. All rights reserved.

Divine Law in the Flesh: God and Man in the Liturgy

By Christopher Carstens, EditorChristmas celebrates the Incarnation of the Son of God. And while this truth is obvious even to the youngest child, it is perhaps less apparent just how God becoming man applies to the celebration of the sacred liturgy. Fortunately, Christians today are beneficiaries of the wisdom which our forefathers accumulated in their struggle to understand how the Second Person of the Trinity could take on a human nature.

After the Council of Nicaea determined definitively that Christ was God, rejecting Arius’s claim that Christ was simply the highest of God’s creatures, bishops and theologians still sought to articulate the “mechanics” of the Incarnation: was Jesus half-God and half-man? Or was he a God inhabiting a human guise? Or a God-man mixture that was a third kind of being altogether? In fact, there were numerous theories put forth to try to understand the truth of the matter.

A significant step forward came at the Council of Ephesus in 431, and at the expense of Nestorius, the Archbishop of Constantinople, who put forth the idea that the incarnate Christ was, in essence, both a human person and a divine person, as well as possessing a human nature and a divine nature. (At the risk of oversimplifying this distinction, “person” describes who one is; nature describes what a thing is—e.g. Who am I? Christopher Carstens. What am I? A human being). Consequently, Nestorius said, Mary was not the mother of the divine person (she was not Theotokos) but of the human person simply. In response, however, the Council taught that Jesus is not “two persons,” but one: the Second Person of the Holy Trinity—and Mary was his mother. In a certain sense, the now-notorious Nestorius was emphasizing and even safeguarding the human dimension in the incarnate Christ, although (unfortunately for him) at the expense of our Lord’s divinity.

Another fine-tuning of our understanding of the Incarnation came 20 years later at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. Here, the priest and monk Eutyches took the issue to the other extreme, claiming that in Christ the human nature “morphed” and mixed with the divine nature. This monophysitism, as it came to be called, was rooted in a kind of skepticism of things created and human. Hence the human nature of the incarnate Christ had to give way and change into something greater, namely, divinity. The heresy of monophysitism, then, while emphasizing the divinity of the incarnate Christ (which is good), downplayed and even denied the humanity of Christ (which, for Eutychus, is bad).

So, what is the proper understanding of God-become-man? What is (in the words of priest and liturgical theologian Louis Bouyer) the “Law of the Incarnation” that we have been blessed to inherit? It is that the incarnate Christ is one divine person—God the Son—

Readers’ Quiz: Baptism

The start of a new year brings with it the hopes for a new life: new health, new habits, new efforts at the spiritual life. In this light, we’re turning our attention to that great sacrament of rebirth: Baptism. More effective than any self-help book and more powerful than the latest health fad, Baptism removes sin, joins us to the Church, and enables us to be men and women fully alive. What do you know about this great gift of grace you have been given?

1. Where in the church does the rite of baptism begin?

with two complete and unmixed natures—human and divine.

Whew! We should be grateful that we ourselves didn’t have to struggle to come to such an understanding but have it given to us by the Church. Still, there’s an ever-present hazard that we could break this Law of the Incarnation when we celebrate the sacred liturgy. That is, just as errors have occurred in our understanding of the Incarnation by either denying aspects of Christ’s divinity or eclipsing elements of his humanity, so the liturgy can do the same. This should not surprise us: while Christ is present in numerous ways in the Church and the world today, it is the liturgy (and especially the Mass) that manifests his presence—one divine person in two united yet distinct natures—most perfectly.

What does a Monophysite Mass look like? Just as Eutyches et al saw in the incarnate Christ a transcending of the human element, a Monophysite-tending liturgy may put up a “wall of Latinity” (to use Pope Benedict XVI’s phrase) that is a barrier for most modern men and women. Bouyer himself mentions a “rubricist mentality” that at times treats liturgical norms as if they themselves were delivered directly by God and, on the whole, don’t allow for any adaptation to the needs of modern men and women. The idea of the liturgical mystery is often misunderstood by this mindset as an impenetrable secret rather than the plan of God’s mind revealed in time to save all things in Christ—a plan to be known, celebrated, and proclaimed to all. As Bouyer summarizes, “all that could make the liturgy a living thing, all that would help the people to share in it, is considered a profanity—as if the liturgy could only retain its sacred character by being removed from any contact with the common man” (Rite and Man, 6).

4. What are the Church’s guidelines for baptismal names?

a. Must be a family name.

b. Must be a saint name.

c. Must not be a weird name.

d. Must not be foreign to Christian sensibility.

5. Imagine a colder than normal day on the North Pole [work with me here!], and only solid ice rather than liquid water was available for use in baptism. Such an action would be:

a. Valid but illicit.

b. Invalid but licit.

c. Invalid and illicit. d. Valid and licit.

In contrast, a Nestorian-leaning liturgy, like its unfortunate namesake, errs on the other extreme by emphasizing the humanness of the Mass and sacraments at the expense of the divine. How? Chalices and patens become everyday cups and plates. Presidential style ceases to differ in any way from the mannerisms of the average man on the street. Music and architecture cease to distinguish themselves from popular forms of art. Even the smallest amount of Latin is not allowed (a “wall of vernacularity”?), often by (wrongly) invoking the Second Vatican Council. And being in church is no different from being at home, at school, or at work. “According to the Nestorian concept,” concludes Bouyer, “everything about the Mass should recall a profane meal, even to the inclusion of mundane conversations” (Rite and Man, 9).

Bouyer applied this “Law of the Incarnation” in his 1963 classic Rite and Man (recently republished by Cluny Media). He and others had in mind a Monophysite-trending liturgy of 1923. But he must have experienced a sort of spiritual whiplash when he witnessed the Nestorian-trending celebrations of 1973.

But how would Bouyer—and how would you—describe our liturgies of 2023? Are they mundane activities that downplay their divine origin? (And isn’t this a significant reason why the preconciliar liturgy has gained popularity over the last decades?) Or are they foreign affairs that don’t nourish us and appear to have little to no bearing on human life? Or—ideally—are they soundly orthodox, following faithfully the Law of the Incarnation, revealing as fully as possible the transcendent divinity of Christ through fully human forms?

While we still bask in the incarnate light that has entered our darkness, and as we consider what New Year’s resolutions are worth continuing, let us take an honest look at our liturgies. For the Incarnation—in Christ and his liturgy—is not just a good idea: it’s the law.

most definitive and authoritative institution of the sacrament of Baptism.

8. Which biblical story helps explain why nine out of ten baptismal fonts has eight sides?

a. The creation of the cosmos.

b. The story of the Great Flood and Noah’s ark.

c. The resurrection of Jesus.

d. All of the above.

e. None of the above.

9. Which of the following elements appears in both the Order of Baptism for Children and in the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults?

a. Entrance.

b. Nave. c. Ambo. d. Font.

2. Which of the following are requirements for a godparent?

a. Be a relative or close friend of the candidate or family.

b. Must have completed his or her 16th year.

c. Not be the mother or father, or grandmother or grandfather of the candidate.

d. Must be at least baptized.

3. True or False: Grandma should baptize her grandchildren if the parents will not.

6. Which of the following Old Testament accounts is a prefigurement of Baptism?

a. Moses leads the chosen people out of Egypt through the Red Sea.

b. Joshua leads the chosen people into the Promised Land through the Jordan.

c. Elijah leads Elisha through the Jordan River before he (Elijah) is taken up by the fiery chariot.

d. Naomi leads Ruth from Moab to Bethlehem through the Jordan River.

e. All of the above.

f. Options a and b.

7. True or False: The baptism of Jesus in the Jordan is the

a. The sponsor/godparent marks the candidate with the sign of the cross at the beginning of the rite.

b. The newly-baptized vests in an alb after emerging from the waters of the font.

c. The candidate for baptism is anointed with the Oil of Catechumens prior to baptism.

d. The newly-baptized is anointed with sacred Chrism following the baptism with water.

e. All of the above.

f. None of the above.

10. True or False: The gifts of the Holy Spirit are bestowed at Baptism.

Continued from BENEDICT, page 1 ping—orthodoxy—is the gift par excellence that is given to us by the faith.”3

Here is an insightful elaboration on the old saying, dating from the fifth century: ut legem credendi lex statuat supplicandi, “Let the law of prayer establish the law of belief.” In other words, the Church’s public worship is an expression of and witness to her infallible faith, and it should help us to understand in a profound way that is more than verbal that all our aspirations for goodness, for truth, for beauty and for love are grounded and find their fulfilment in the allsurpassing reality of God.

Game-changer

As a theologian, Joseph Ratzinger remained true to this fundamental intuition throughout his long and distinguished career. Although not a liturgist by training (a point often noted by his critics), he touched upon matters of divine worship in various publications. Ratzinger was deeply indebted to the principles of the 20th-century Liturgical Movement, shaped by figures such as Romano Guardini and Joseph Pascher. At the same time, it was his concern for authentic liturgical renewal that made him question aspects of the post-conciliar reform already in its early, enthu-

siastic years. Ratzinger’s perceptive analysis exposed the ambivalence of a liturgical purism that oscillated between a revival of a supposed “golden age” (whether pre-Carolingian, or pre-Nicene), and an uncontrolled urge for novelty.4 What fell by the wayside was the historical growth and development of the liturgy in the Middle Ages and the Baroque period, which brought depth and maturity that cannot easily be disposed of. It is the Catholic liturgy in its organic (and sometime meandering) history that nourished many generations of Christian people, including its greatest saints. In particular Ratzinger was one of the few but notable voices (along with Louis Bouyer, Josef Andreas Jungmann, and Klaus Gamber) that questioned the sweeping introduction of Mass “facing the people” and the ensuing re-ordering of churches throughout the world.

A milestone in Ratzinger’s theological work on the liturgy was the collection of essays The Feast of Faith, first published in German in 1981.5 Among the significant contributions of this book was Ratzinger’s argument that the Last Supper established the dogmatic content of the Eucharist, but not its liturgical form, which was yet to develop. In other words, the Mass is not simply a re-enactment of the Last Supper,

but the Last Supper itself must be understood as the anticipation, under the veil of the sacramental signs, of the sacrifice of the Cross. This insight led Ratzinger to propose a robust re-affirmation of the sacrificial character of the Mass: the Eucharist as the “banquet of the reconciled” is integrated into the self-offering of Christ made present on the altar in the form of a liturgical rite indebted to Synagogue and Temple. Against this background, Ratzinger restated his preference for the celebration of Mass “facing East” as the more suitable, visible, and ritual expression of the Eucharistic sacrifice.

As Cardinal and Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (1981–2005), Ratzinger continued to engage with the theology of the liturgy.6 The broad scope and heavy burden of his office entrusted to him by Pope John Paul II allowed him to write only one monograph: The Spirit of the Liturgy, published in 2000.7 This book was nothing short of a game-changer, and I am convinced that in due time it will be seen as a watershed in Catholic liturgical study and practice . The Spirit of the Liturgy inspired a new generation of scholars to look beyond the grand narrative of the post-conciliar reform and look again to the fullness of liturgical tradition. The book also encouraged clergy and faithful alike to articulate their unease about the present state of Catholic worship, where not everything is well. In many ways, The Spirit of the Liturgy was a synthesis of Joseph Ratzinger’s work and thought on the subject and did not break as much new ground as The Feast of Faith. The book’s major contribution may well be his effort to deepen and broaden our understanding of “active participation,” the principle that lay at the heart of the Second Vatican Council’s call for liturgical renewal. The need to go beyond the external and superficial interpretation of this principle in the post-conciliar reforms is widely recognised today. Ratzinger gave this conviction a sound theological footing, when he wrote in a subsequent publication: “The liturgy derives its greatness from what it is, not from what we do with

it…. Liturgy is not an expression of the community’s consciousness, which in any case is diffuse and changing. It is revelation received in faith and prayer.”8

A New Liturgical Movement

Joseph Ratzinger lived and worked at a time when precisely the form and expression of this revelation received in faith and prayer had become a highly controversial topic in the Catholic Church. As a theologian and cardinal, he did not shrink from entering this contested arena with courage and clarity. With his election to the See of Peter on April 19, 2005, Benedict XVI found himself in a position to shape the future of the Catholic liturgy, a position he could only approach with some misgivings, because he strongly held that authentic liturgical renewal does not happen simply by decrees and instructions.

Hence Benedict XVI began cautiously by conveying in his homilies and discourses, and in a special way in his own liturgical celebrations, the Second Vatican Council’s order of priorities as his own first concern: namely, that the sacred liturgy must be a reflection of the glory of God—in which we are called to share above all through the self-offering of Christ at the altar, when we are immersed in the Paschal Mystery of his passion, death, and resurrection. This sacramental communion is not just something we (the community assembled at a particular place and time) do but the gift of a greater reality Christ entrusted to the entire Church. Shortly before his election to the papacy, Ratzinger called for a renewed awareness of the liturgical rite as “the condensed form of living tradition.”9 This meant, in concrete terms, to reconsider the process of liturgical renewal according to the hermeneutic of reform in continuity in interpreting the Second Vatican Council, which Benedict XVI proposed in his momentous discourse to the Roman Curia on December 22, 2005.10

Already in his Memoirs of 1997, then-Cardinal Ratzinger called for a “new liturgical movement” that would “call to life the real heritage of the Second

“The Spirit of the Liturgy, published in 2000, was nothing short of a game-changer, and I am convinced that in due time it will be seen as a watershed in Catholic liturgical study and practice.”

Vatican Council,” a claim he later took up again in The Spirit of the Liturgy. He was convinced that infelicitous choices have been made in the actual implementation of the sound principles of the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy. Not enough attention has been paid to article 23 of the document, insisting that “there must be no innovations unless the good of the Church genuinely and certainly requires them; and care must be taken that any new forms adopted should in some way grow organically from forms already existing.”

In a lecture held at the occasion of the 40th anniversary of Sacrosanctum Concilium in 2003, Ratzinger argued that the time had come for a relecture—a rereading—of the conciliar constitution. With the aim of overcoming simplistic readings of “the council,” Ratzinger proposed a distinction between two different levels that run through every chapter of the document. In the first place, Sacrosanctum Concilium “develops principles that quite fundamentally and generally concern the nature of liturgy and its celebration” and command the highest authority. Secondly, and based on these principles, the constitution “gives normative instructions for the practical renewal of the Roman liturgy.” For Ratzinger these valid instructions “are also more products of their time than the statements of principle.”

relecture, guided by a hermeneutic of continuity in his 2007 motu proprio Summorum Pontificum by lifting previous restrictions on the use of the pre-conciliar liturgical books, which he called the Extraordinary Form or usus antiquior of the one Roman Rite. This conception is not without its difficulties, because there is an obvious discontinuity between pre-conciliar and post-conciliar liturgical forms. Such differences are less pronounced when, for instance, the current Missal is celebrated in Latin and at an altar with the priest facing east (ad orientem) instead of facing the people, but the differences still remain: in the prayers and readings of the Mass, in many ritual elements, and in the structure of the liturgical year. In my reading, with his affirmation of “two forms of the same rite” Benedict described his goal of a slow and gradual process that was meant to begin with Summorum Pontificum and could eventually result in a “mutual enrichment” of the two forms. Pope Francis rejected this vision in his 2021 motu proprio Traditionis Custodes, and the status of the pre-conciliar liturgical books, while still being used with considerable restrictions, is far from clear. At this point, it is worth recalling the same Paschal Mystery is expressed in different, but by no means contrary or contradictory, ways in the Roman Rite, other Western rites, and in the many Eastern rites—and yet all of them have their place in the Catholic Church.

By calling for a mutual enrichment, Benedict XVI took a courageous step to overcome the tendency to “freeze” the present state of the post-conciliar reform in a way that would not do justice to the organic development of the liturgy, and to resume the liturgical renewal desired by the Council in a different key.12

“Ratzinger cautioned: ‘Someone who does not think that everything in this [liturgical] reform turned out well and considers many things subject to reform or even in need of revision is not therefore an opponent of the ‘Council.’”

At a time when many questions once were considered settled are re-opened for debate, it is difficult to understand why the strengths and weaknesses of the post-conciliar liturgical reform should not be discussed openly. Liturgical renewal is effected by practical and prudential decisions that do not engage the infallibility of the Church in matters of faith and morals.

Anglicanorum Coetibus of 2009, follows this trajectory. The ritual books under the heading Divine Worship, especially the missal (2015), conform to the basic pattern of the Roman Rite, but at the same time enrich it with a “patrimony” that is partly derived from the broader medieval tradition (for instance, in the introductory rites and the offertory) and partly derived from a characteristically Anglican style of prayer, duly harmonized with Catholic doctrine.

Although

A third level is added with the concrete implementation of the liturgical reform by the Consilium, most importantly the renewed Roman Missal implemented in 1969–1970. While these “forms of liturgical renewal established by church authority” are binding, they are “not simply identical with the Council.” The framework

“ The sacred liturgy must be a reflection of the glory of God— in which we are called to share above all through the self-offering of Christ at the altar, when we are immersed in the Paschal Mystery of his passion, death and resurrection.”

set by the broad directives of Sacrosanctum Concilium allows for “different realizations.” Ratzinger cautioned: “Someone who does not think that everything in this reform turned out well and considers many things subject to reform or even in need of revision is not therefore an opponent of the ‘Council.’” At a distance of forty years, he said, the text of Sacrosanctum Concilium should be “newly ‘contextualized,’ that is, read in the light of its impact in recent history and of our present situation.”11

“Two Forms…Same Rite”

As pope, Benedict offered a key instance of such a

The blueprint for Summorum Pontificum is available in Ratzinger’s concluding reflections at a liturgical conference held in the Benedictine Abbey of Fontgombault in 2001. At that occasion, the Cardinal spoke of a “reform of the reform,” for which he identified three areas. Firstly, he saw the need to overcome “false creativity, which is not a category of the liturgy,”13 by which he meant ambiguous elements in the postconciliar liturgical books that contributed to ritual instability—including, above all, the options for adapting rites to given circumstances, and the frequent ad libitum passages (“with these or similar words”). The fundamental problem Ratzinger identified in such arbitrary indications is not just liturgical in nature (interrupting, for instance, the flow on which “successful” ritual depends) but also problematic in an ecclesiological context: “with this false creativity, which transforms the liturgy into a catechetical exercise for this congregation, the liturgical unity and the ecclesiality of the Liturgy are being destroyed.”14 Secondly, Ratzinger addressed the question of the post-conciliar liturgical translations. This matter has been widely treated, especially in the Anglophone world, and a genuine process of renewal started in the pontificate of John Paul II. Thirdly, Ratzinger raised again the question of Mass “facing the people.” His modest proposal was at least to place a clearly visible cross on the altar so that both priest and people would have a common focus of direction.15

Gentle Pastor

Benedict XVI was keenly aware that the manifest discontinuity in the ritual practice of the Church has created a situation in which a mere imposition of traditional liturgical forms would be widely perceived as yet another rupture. By opening new possibilities, he intended to create favorable conditions for an “organic” development of the Roman Rite that would avoid the discontinuity that did so much damage to Catholic ritual in the postconciliar period. The liturgical provision for the Personal Ordinariates for former Anglicans, created after the apostolic constitution

It seems to have been the idea of Benedict XVI that organic development needs to happen as if by osmosis, that is, a steady and almost unconscious assimilation of the liturgical tradition. An important element in this process was to be the pontiff’s example in his own celebrations. Ritual elements such as the placing of a prominent crucifix in the center of the altar, the distribution of Holy Communion to the faithful kneeling and directly on the tongue, and the extended use of the Latin language were intended to set a standard to be imitated. Benedict was convinced that authentic liturgical renewal does not come about by instructions and regulations. His reticence as a lawgiver—for instance, there was no new editio typica of any liturgical book during his pontificate—could be interpreted as a lost opportunity. On the other hand, the fragility of legislative decisions was demonstrated when his immediate successor, Pope Francis, cancelled the provisions of Summorum Pontificum

Against the odds, Pope Benedict did open perspectives for a renewal in continuity with the liturgical tradition, and these impulses have been taken up especially by younger generations in the Church throughout the world. This “new liturgical movement” Joseph Ratzinger desired has the potential to mend the torn threads of Catholic ritual. The best testimony to his liturgical legacy will be to continue his work with patience, perseverance, joy, and gratitude for his luminous theological mind and his long-suffering service to the people of God.

Father Uwe Michael Lang, a native of Nuremberg, Germany, is a priest of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri in London. He holds a doctorate in theology from the University of Oxford, and teaches Church history at Mater Ecclesiae College, St. Mary’s University, Twickenham, and Allen Hall Seminary, London. He is an associate staff member at the Maryvale Institute, Birmingham, and on the Visiting Faculty of the Liturgical Institute in Mundelein, IL. He is a Corresponding Member of the Neuer Schülerkreis Joseph Ratzinger / Papst Benedikt XVI, a Member of the Council of the Henry Bradshaw Society, a Board Member of the Society for Catholic Liturgy, and Editor of Antiphon: A Journal for Liturgical Renewal.

1 Joseph Ratzinger, Milestones: Memoirs 1927–1977, trans. Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis (San Francisco: Ignatius, 1998), 18-20.

2 Benedict XVI, “On the Inaugural Volume of My Collected Works,” in Joseph Ratzinger, Theology of the Liturgy: The Sacramental Foundation of Christian Existence, Joseph Ratzinger Collected Works 11, ed. Michael J. Miller (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2014), xv-xviii, at xv.

3 Benedict XVI, “On the Inaugural Volume of My Collected Works,” xv

4 Joseph Ratzinger, “Catholicism after the Council”, in The Furrow 18 (1967), 3–23, at 10.

5 Joseph Ratzinger, The Feast of Faith: Approaches to a Theology of the Liturgy, translated by Graham Harrison (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1986).

6 See especially Joseph Ratzinger, A New Song for the Lord: Faith in Christ and Liturgy Today (New York: Crossroad, 1996).

7 Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, translated by John Saward (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000).

8 Joseph Ratzinger, “The Theology of the Liturgy,” in Theology of the Liturgy, 541–557, at 557 (originally published in 2001).

9 Joseph Ratzinger, “The Organic Development of the Liturgy,” in Theology of the Liturgy, 589–594, at 591 (originally published in 2004).

10 Benedict XVI, Address to the Roman Curia Offering Them His Christmas Greetings (22 December 2005); see also Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation on the Eucharist as the Source and Summit of the Church’s Life and Mission Sacramentum Caritatis (22 February 2007), no. 3.

11 Joseph Ratzinger, “Fortieth Anniversary of the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy: A Look Back and a Look Forward,” in Theology of the Liturgy, 574–588, at 576 (originally published in 2003).

12 See Benedict XVI, Video Message for the Closing of the 50th International Eucharistic Congress in Dublin (17 June 2012).

13 Joseph Ratzinger, “Assessment and Future Prospects,” in Theology of the Liturgy, 558–568, at 565 (originally published in 2003).

14 Joseph Ratzinger, “Assessment and Future Prospects,” 565.

15 See Joseph Ratzinger, “Assessment and Future Prospects,” 565–566.

“By opening new possibilities, Pope Benedict intended to create favorable conditions for an ‘organic’ development of the Roman Rite that would avoid the discontinuity that did so much damage to Catholic ritual in the postconciliar period.”

Face to Face and Eye to Eye: A Reflection on Eucharistic Adoration

By Father Justin Kizewski

By Father Justin Kizewski

Imagine that you are on pilgrimage to Jerusalem during one of the high feast days during the first century. As you approach the outside of the temple, you notice a commotion. The priests are lifting up the holy bread (known also as “showbread”) on a golden table for everyone to see, saying, “Behold God’s love for you.”

The showbread of the Temple has a very interesting history in itself that may date back to Melchizedek (see Brant Pitre, Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist, 127). Melchizedek is that mysterious priest, king of Salem (“salem” means peace—you and I know this priest-king’s town as Jerusalem). Melchizedek feeds God’s pilgrim people in the persons of Abraham and his companions with a sacrificial offering of bread and wine. That priestly sacrificial offering of bread and wine was repeated in the Temple liturgy on a weekly basis. The priests would bake bread with incense mixed into it, and then pass it through the Holy of Holies before leaving it on a table in the sanctuary next to the tabernacle for the next week. The old bread that was replaced would be consumed by the priests.

The showbread makes an earlier appearance in the life of David and his troops. They are hungry and in need of food. Escaping from the threats of King Saul, David and his soldiers are given the holy bread of the Tent of Meeting to eat. Typically, by this time, this bread was only eaten by the priests. This gesture suggests that David and his companions are also priests, and indeed they are. They are priests according to the order of Melchizedek (Pitre, 137). I draw attention to it now because it can provide an Old Testament example and anticipation of what is a far greater gift in the Eucharist.

Consider the other names for what often gets called “showbread” in our translations. It is also known as the “Bread of the Presence”; or again, it is called “Bread of the Face of God” (Pitre, 121). It was something from the Holy of Holies that all were allowed to see. It is alluded to in this line from the book of Exodus: “They beheld God, and ate and drank” (Exodus 24:11, Pitre, 121). The Bread of the Face of God was a memorial, a remembrance, of a heavenly banquet during which Moses and the elders had “seen” God.

What can we learn from these thoughts? When you and I are at Eucharistic Adoration, we are looking at the True “Bread” of the Presence, the Face of God. Adoration can remind us of those times in which we participated in the heavenly banquet, those times in which we “saw” or certainly experienced God’s love. We can think of those times he fed us in famine or rescued us from a threat. We can gaze at the true “Bread” of Presence and of the Face of God and remind ourselves of what the Old Testament priests said regarding its precursor: “Behold how God loves you!”

Look and See!

In fact, whenever we pray, it is good to begin by calling to mind the presence of God and how God looks at us. Try and imagine his gaze, his face. Spoiler alert: His gaze is always and only one of love. It is possible that his gaze of love will cause us pain if we are stuck in sin, or if we are conscious of any of our many betrayals. However, this feeling says more about us than about God. His gaze is one of love. His gaze can be one of purifying love if we allow it to be (cf. Luke 22:61). Perhaps his gaze prompts us to go to confession so that we can hear the voice that accompanies that look of love: “I absolve you from your sins.”

We can also see the gaze of love and be comforted. Looking at our Eucharistic Lord and imagining his gaze should console us. What we see explicitly is the gift of himself to us. The gift that reveals what love is. “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:15). “I lay down my life…. No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord” (John 10:17-18). “Take, eat…this is my body which is given for you” (Matthew 26:27; Luke 22:19).

In the Eucharist, we experience the gaze of love of Jesus Christ. But, we also experience the gaze of love of the Father. The Son was sent to reveal the Father. Jesus is what it looks like when God becomes man. When we see him, we see the Father (cf. John 14). He promises that anyone who comes to him, he will show the Father to him (Matthew 11). What we see in Jesus Christ’s passion and death is the work of the Father’s love. This work is what we see at Mass.

I set this up as the work of the Father that we see on Sunday or anytime we are at Mass or Adoration for a very important reason. Jesus’ response to the accusation that he was working on the sabbath was this: “My Father is working still, and I am working” (John 5:17). His work reveals the work of the Father. In fact, the work of the Sabbath reveals the work of the Father. In this light, we can see the significance of the Lord’s words when his disciples are criticized for picking the heads of grain and eating

The monstrance often resembles the sun with rays bursting from the center. Have you ever gone outside and turned your face toward the sun and soaked in its rays? Taking in moderate amounts of sun can teach us something about any time we spend in front of Christ. We are changed. We are warmed, even baked, by the sun. Sitting before the Lord in the Eucharist, we are similarly changed, but spiritually speaking. We can receive greater hues of color and greater depths of warmth. Life abounds. We are like Moses on the mountain whose face was radiant or like Christ at the Transfiguration.

them on a Sabbath. The Pharisees are upset that Jesus’ disciples are doing what is unlawful on the Sabbath. Jesus asks them if they have read about David’s entry into the house of God and eating the bread of the Presence. He draws attention to the work of the priests who work on the Sabbath while remaining guiltless. His disciples, the priests of a new covenant, work to show forth the work of the Father, just like Jesus does. He concludes, “I tell you, something greater than the temple is here. And if you had known what this means, ‘I desire mercy, and not sacrifice,’ you would not have condemned the guiltless. For the Son of Man is Lord of the Sabbath” (Matthew 12:1-8). What or who is greater than the Temple? God himself, the One we see in the true Bread of the Face of God.

The apostles, by dealing with grain and eating it, reflect the eating of the Bread of the Presence by a more universal priesthood which shows forth the work of the Father by a sacrifice of bread and wine. Sound familiar? The Temple that is reflected in this Bread of Presence is the Body of Christ. It is the work of priests that reveals the work of the Father because it is the work of the Son. When we are at Adoration we can think of these gifts and the way that Christ is Lord of the sabbath, that he is the new way of being like God, the new way of God being with us. His body is the new temple and the new bread from heaven— an image of the Manna.

The Bread of the Presence was a sign that led the pilgrims deeper. It was a connection to the goings on in the sanctuary, a sign of the Temple. It was a sign of God’s work in saving his people. It was a sign of God’s love. It was meant to draw them deeper into the participation of the heavenly banquet. Eucharistic Adoration can be all of this for us. When we see the Eucharist, we can think of the Mass. When we see the Eucharist, we can be reminded of the presence, of the One greater than the Temple. When we see the Eucharist, we can recall God’s love for us. All of this is because the Eucharist is Christ, the “greater than the Temple,” the Lord of the Sabbath, the revelation of the work and love of the Father.

We are not just meant to look at the Son and see the Father; we are meant to grow in our identity as sons and daughters. When at Adoration, we can ask the Lord to show us the Father. We can ask him to make us more like sons and daughters..

St. Thérèse Lisieux compared the appearances of the Eucharist to a curtain, to a veil. On the other “side,” so to speak, of this veil is not the bride, but the groom. A fellow priest calls looking at the Eucharist “beholding the groom beholding the bride.” In the Eucharist, we see the Groom’s regard for his Bride. The Groom is Jesus. We can image the movements behind the curtain and the invitation to the wedding feast of the lamb. We are brought into this spousal relation with Christ so that his Father becomes our Father. We share his name in a covenantal relationship. We can look at the Eucharist like we would look at a spouse. We can look through him and see the relationship we have with his Father.

Here Comes the Son

Since we are thinking about the Son, we might also think in terms of the sun. I would tell children S-O-N not S-U-N, but there are similarities. The monstrance often resembles the sun with rays bursting from the center. Have you ever gone outside and turned your face toward the sun and soaked in its rays? I close my eyes and thrust out my chin and try to absorb the sun’s warmth, light, and life-giving qualities. This metaphor would dim eventually because you can spend too much time in the sun, but taking in moderate amounts of sun can teach us something about any time we spend in front of Christ. We are changed. We are warmed, even baked, by the sun. Taking in the sun can be a Eucharistic image. Sitting

before the Lord in the Eucharist, we are similarly changed, but spiritually speaking. We can receive greater hues of color and greater depths of warmth. Life abounds. We are like Moses on the mountain whose face was radiant or like Christ at the Transfiguration.

At the Transfiguration, Peter perceived that he was in the presence of God or that God was truly dwelling with him in Christ Jesus. God had pitched his tent in his Incarnation and Peter wanted to construct tents to dwell there with him, in the midst of the cloud, with heavenly witnesses. What Peter wanted, time to stay on the mountain-top, is what we have in any time of Adoration. We have time to dwell with our transfigured Lord— transfigured now, not in a way that reveals his divinity and glorified humanity, but in a way that hides it. But the definitive dwelling of God with his people, the way that he does stay with us and so answers the disciples of Emmaus’s prayer (cf. Luke 24), awaits us in Adoration.

We have spoken of presence, and the Son and the Father. We can use an image of a mother and child to help us if we find from time to time that during Adoration our minds wander. We may sit in silence in Adoration without much actually happening. This silence for us may seem empty, or boring, or absent. However, “God’s silence is never ambiguous” (Acklin and Hicks, Personal Prayer: A Guide for Receiving the Father’s Love, Steubenville: Emmaus Road, 2019, 73). His silence isn’t awkward, or a silent treatment. He isn’t mad at us. Remember, his gaze is always one of love. His silence is like the silent gaze of a mother upon her sleepy newborn. Acklin and Hicks offer this image as one describing God’s silence in our prayer (cf. Acklin and Hicks, 64-65; 72), but it is also helpful in thinking about our wandering minds. I think it can be easy for us to get down on ourselves for not paying attention in Adoration to the love and person truly present in the Eucharist. However, this might be because we don’t really understand his love. I think his love, reflected here in the relationship between mother and child, is more abiding. Imagine the mother gazing at her sleeping baby. The baby stirs, opens its eyes, and makes eye contact with her mother. Eye meets eye. The mother is understandably thrilled. Her heart leaps: “My baby looked at me!”

I imagine those times where the Lord brings our attention back to him or we are able to focus, if ever so briefly on him in the Eucharist. It is like the baby opening his eyes and catching the eyes of his mother. I imagine a similar metaphorical excitement on the Lord’s part. He looked at me. Remember, the Lord loves. He loves passionately. Why wouldn’t he get excited when the one he loves takes notice of him?

Adoremus

Meeting gaze with gaze or eye to eye does conjure up the notion of Adoration. The word adoration literally suggests a kind of face to face or even more vividly mouth to mouth (coming from the Latin ad ore—“to the mouth”). We have connotations of a kind of intimacy, but also, in this strange way of tasting. Adoration should lead us to consuming the Word in the flesh. Adoration does lead us to consume the true bread from heaven that is given for the life of the world (cf. John 6). St. Augustine will bring it home for us. Commenting on how the earth is God’s footstool (Psalm 98:5), the Bishop of Hippo speaks about the appropriateness of adoring the flesh of Jesus. He says, “I turn to Christ…and then I discover how God’s footstool may be adored…. He took earth from earth, because flesh comes from the earth, and he received his flesh from the flesh of Mary. He walked here below in that flesh, and even gave us that flesh to eat for our salvation. But since no one eats it without first worshipping it…, not only do we commit no sin in worshipping it; we should sin if did not” (Augustine, Expositions of the Psalms 73-98, tr. Maria Boulding, New York 2002).

When we look at the Eucharist, we see the Flesh of the One whose mother carried him in her womb and bore him into the world. Analogously, when we adore the Eucharist, we should bear in mind that we are meant to receive him fruitfully and “give birth” to him in our daily life. Mary, Mother of the Eucharist, pray for us.

Father Justin Kizewski, MS, MA, PhL, STD, ordained in 2008, is a priest from the Diocese of La Crosse. He is Coordinator of Intellectual Formation at St. Francis de Sales Seminary in Milwaukee and adjunct professor of theology at Sacred Heart Seminary and School of Theology. Previously he was a pastor of two parishes in Chippewa Falls, WI. His graduate studies were done in health care bioethics, philosophy, and theology. He has previously taught for Christendom College, Saint Paul Seminary, and the Gregorian University.

How Pastoral Concerns and Canonical Reforms Inflated the Sabbath and Deflated Its Importance

By John GrondelskiMany liturgical reforms called for or attributed to the Second Vatican Council have been flashpoints ever since they were introduced. One post-Vatican II development that has garnered little discussion (much less controversy) has been the practice of celebrating the Sunday liturgy on Saturdays. The practice is so settled in the United States that questioning it seems almost akin to a politician grabbing on to the third rail of Social Security reform. Outside the United States, the practice seems to have varied reception: my experiences in England, Poland, and Switzerland were that it existed but clearly stood in the shade of Sunday. In China, where clergy are more limited, practice in the English-speaking expatriate community more closely resembled that in the United States.

Between the prudence of questioning a popular practice and the current pontificate’s apparent posture that any public doubts about the wisdom of any practices claiming a connection to the Second Vatican Council is liturgical revanchism, I will raise some questions about the practice of celebrating Sunday Masses on Saturdays. I do so because I maintain that the practice in its origins—as opposed to mythology about its origins—is wrought with various kinks that collectively affect coherent liturgical practice.

Where Did Saturday Night Mass Come From?

Pace an oft-repeated myth that celebrating Sunday Masses on Saturday nights was intended to put Catholics as “spiritual Semites”1 back in touch with their Jewish roots about beginning the day from sunset of the previous evening, the origins of the practice were far more canonical, convoluted, and, arguably, “pastoral.” Shawn Tunink’s 2016 thesis at The Catholic University of America for a licentiate in canon law, which I summarize and follow here, traces the path.2

The path to Sunday Masses on Saturday nights arguably comes, at least indirectly, from Sunday Masses on Sunday nights. In the first half of the 20th century, the Eucharistic fast extended from the previous midnight, which practically anchored Sunday Masses to Sunday mornings.3 Tunink notes, however, that before Pope Pius XII’s mitigations of the Eucharistic fast in the 1950s, Rome had already thrice authorized Sunday evening Masses: (1) in the Soviet Union, (2) in Europe during World War II, and (3) for French prison chaplains in the immediate postwar period.4

After the War, two forces seemed to combine to make permission for Sunday evening Masses permanent: their popularity, especially in postwar occupied Germany, and changes to work schedules, often made with an underlying ideological edge. German Catholics liked Sunday evening Masses. The Polish bishops asked for Sunday evening Masses because the communist regime rearranged workers’ schedules to keep them away from churches. Some similar forces were probably operative as a postFrench Revolution leftover in ever-laicité France.5 Broader permissions for Sunday night Masses were granted out of pastoral considerations, to “open up to the faithful a new source of grace”6 ever more broadly in Europe. When Pope Pius XII modified the Eucharistic fast—first in 1953 by excluding water from it and allowing additional non-alcoholic beverages, especially for clergy when faced with extended hours for celebration of Mass, then in 1957 by reducing the fast to three hours prior to receiving Communion— the groundwork was laid for Mass to be celebrated at any time on Sundays.7

democratic societies might have been more resistant to those demands if the Church did not accommodate them (and thereby inadvertently accelerating secularization), I cannot say.

What is important is that the precedent for changing canonical discipline about Mass times in the name of pastoral accommodation was made. In the 1960s, the accommodation would be made even more elastic through the canonical decision to treat Masses celebrated on Saturdays as fulfilling the dominical precept of attending Sunday Mass.

Already in 1964, Vatican Radio spoke about permissions granted in particular areas—usually in the name of the faithful’s limited access to priests and/ or the limited number of clergy—to justify attending Mass on Saturday evenings to fulfill the Sunday Mass obligation.8 Permissions for that practice seem to have grown quietly in the Europe of the mid-1960s (anecdotally said to be especially in France) until, by 1967, the Sacred Congregation on Rites’ Instruction, Eucharisticum Mysterium (no. 28) formalized that the principles under such permissions could be

“pastoral statement” of the Catholic bishops of the United States to dispense from mandatory abstinence on non-Lenten Fridays provided some other act of voluntary penance was substituted,11 many Catholics seem to have adopted the permission but ignored the caveat.

It should be noted that the Catholic bishops of the United States thrice received Rome’s permission—in 1970, 1974, and 1979—to allow a Saturday evening Mass to fulfill the Sunday Mass obligation. They only ceased needing the permission because the 1983 Code of Canon Law made the permission universal and permanent.12

What Is the Theological Basis?

The historical record shows that the rationale for allowing a Saturday Mass to fulfill the dominical precept had nothing to do with theology and everything to do with canonical mandate. In the context of the original decision to allow for Saturday evening celebration of Sunday Mass, there are no documents discussing the Jewish concept of the day as beginning the evening before, of Saturday evening Masses being some sort of “vigil,” of expanding our celebration of the Sabbath rest, or of any other justification from the viewpoint of liturgical theology. There was no rationale, only a clerical fiat empowered by canon law: competent ecclesiastical authority could declare Saturday night “counted” for Sunday—and that was that. Any theological justifications appear to be post-factum veneers applied to a legal fiction to regard Saturday night as “Sunday.”

No doubt defenders of the status quo would maintain that the decision was driven by a generous pastoral adaptation of Church law. While one can have a certain sympathy for such motivations, it does not free us from examining its other consequences.

Some proponents no doubt saw the extension of the dominical precept to include Saturday evenings as a further application of the pastoral generosity first expressed in permitting Sunday Masses on Sunday evenings. But nobody ever doubted Sunday evenings were part of Sunday. The problem was not making Sunday evening “part” of Sunday but overcoming the practical impact of the Eucharistic fast which began at midnight that would then extend for 16-20 hours.

That Saturday evenings were “part” of Sunday was a completely different kettle of fish. That the Church considered application of the dominical precept to Saturday evenings a canonical matter is reflected in the fact that, at first, the question was whether a Mass celebrated on Saturday evening using the liturgy of that Saturday fulfilled the precept.13 Even today, a Catholic who attends a Mass on Saturday evening that does not include the Sunday liturgy (e.g., a wedding), fulfills the dominical precept. So—as Tunink strongly points out—Saturday night Masses were never a question of extending Sunday14 but of extending the time one could fulfill the obligation to attend Mass on “Sunday.”

AB/SHUTTERSTOCK

Some proponents no doubt saw the extension of the dominical precept to include Saturday evenings as a further application of the pastoral generosity first expressed in permitting Sunday Masses on Sunday evenings. But nobody ever doubted Sunday evenings were part of Sunday. The problem was not making Sunday evening “part” of Sunday but overcoming the practical impact of the Eucharistic fast which began at midnight that would then extend for 16-20 hours. That Saturday evenings were “part” of Sunday was a completely different kettle of fish.

How these two factors—their popularity and the pastoral permission to celebrate Mass later on Sundays to address changed work schedules— affected each other is a question I leave to historians. Expanded work schedules were cited to justify the accommodation, but whether European Catholics in

granted.9 As Tunink notes, Eucharisticum Mysterium did not grant such permission but only stipulated the conditions under which they should be granted.10 The rationale was to give Christians greater facility to “celebrate the day of the Resurrection” provided it did not obscure “the significance of Sunday.” One might observe that, like Rome’s approval of the 1966

I would argue, then, that claims that Saturday night Masses mirror or somehow analogously follow Jewish liturgical practice of reckoning the day from the previous evening were after-the-fact justifications which sought to provide some theological rationale for a canonical decision. That this argument is wholly onesided is evident from the fact that, as previously noted, Sunday evening Masses—even at 9 or 11 pm, as on some college campuses—still are Sunday Masses.

When Saturday night Masses were first introduced, the term used for them was “anticipated,”15 i.e., they anticipated the Sunday obligation to attend Mass. That term has, unfortunately, largely fallen by the wayside. One occasionally hears the claim that Saturday night Masses are somehow “vigil” Masses, but that term is wholly erroneous16 since, other than its initial bandying about, nobody speaks of the “Vigil of the 21st Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year C.” Vigils normally have their own, self-contained liturgies, e.g., the readings of the Easter and Pentecost Vigils—the Church’s greatest vigils—are utterly different from Masses during the day on those solemnities. The same is true of the Vigil Mass for the Assumption on the evening of August 14. On the other hand, regular Sunday Masses on Saturday nights simply use the Sunday readings.

The fact that they are not truly “vigil” Masses is also evident from the American holyday practice, adopted by the bishops in 1991, that waives the obligation to attend Mass on the Assumption, All Saints Day, or the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God if they fall on a Saturday or Monday. When Christmas falls

“ The path to Sunday Masses on Saturday nights arguably comes, at least indirectly, from Sunday Masses on Sunday nights.”

“ The historical record shows that the rationale for allowing a Saturday Mass to fulfill the dominical precept had nothing to do with theology and everything to do with canonical mandate.”

Dies Domini20 laments the erosion of Sunday, but when “pastoral accommodation” refuses to take a stand for the religious rights of Catholics to keep Sunday holy—even out of good motives—it in fact simply fosters the further erosion of the unique identity of that day.

AB/LEVAN RAMISHVILI ON FLICKRfalls on Sunday—as it did in 2022—the Solemnity preempts a lesser feast (which is why the Feast of the Holy Family is transferred to December 30) and Saturday, December 24, features the lectionary of the Vigil Mass for Christmas. As Tunink observes, the Holy See dealt with “back-to-back” celebrations by invoking the calendar of precedence: the higher ranking feast prevails, even if the person attending that Mass intends to fulfill the obligation for the lower feast.17 The Catholic bishops of the United States merely closed the circle by dispensing the faithful from a “back-to-back” obligation.18

What Have Been The Consequences?

Answering this question depends on one’s perspective. If one’s sole motivation is passive “pastoral accompaniment” of the situation in which contemporary Catholics find themselves, these adaptations have been a great success. As many Catholics can attest, Saturday evening Masses are usually one of the best attended of Sunday Masses at the typical American parish.

For those who think that canon law should not be so autonomous from good theology and liturgy but, rather, their servant, and reject a version of canon law that simply treats the question as to whether the competent cleric can “dispense,” “extend,” or “anticipate” the Sunday “obligation,” the answer is more ambivalent. It would start with the question of whether the “obligation” should be driving, rather than deriving from, the theology of Sunday.

Despite the Holy See’s caveats that these pastoral accommodations should not dilute the preeminence of Sunday, that is exactly what happened. Like similar caveats that voluntary abstinence should not eviscerate the penitential meaning of Fridays or that earthen burial is preferable to cremation (tolerated as long as not undertaken out of resurrectiondenying motives), an honest assessment is that the accommodations have greatly eroded the ideal.

Even if these pastoral accommodations were made out of good intentions, they presumed Catholic cultural conditions that were even then largely running on fumes. For consider: by the 1970s, business interests were actively opposing Sunday commerce bans and secularists were challenging blue laws as establishments of religion. Fifty years later, Sunday in the United States is only marginally different in quality from other days.19 It, along with the “Sunday” obligation, has been subsumed into a “weekend” in which religious duties compete with secular choices and responsibilities in an everpressing competition for the Christian’s time. I would add, from experience, that it seems the Catholic propensity to “adapt” has furthered this erosion: when I lived in the largely Protestant city of Bern, Switzerland, 2008–11, all major businesses started closing by 5 pm Saturday, the bells of the city’s churches pealed the Sonneneinleitung (the “invitation for Sunday”) around 7 pm, and everything was closed but restaurants and theaters on Sunday. Some bakeries operated until about noon; afterwards, one could only buy staple goods at gas stations on the highways or at a 24-hour shop in the central train station. In contrast, the Catholic city of Fribourg, also in Switzerland, 30 miles distant and with no such bans, was far more “American.”

So Where Do We Go?

That, too, is a difficult question. As I pointed out at the beginning of this essay, questioning Saturday night Sunday Masses is politically and pastorally unpopular: why attack the likely best-attended parish Mass when overall Mass attendance among Catholics is plummeting? (This is especially true after we’ve all seen how the churches—what with retrospective irony Pope Francis calls “field hospitals”—were almost wholly evacuated during COVID.) This essay is designed as much to elicit discussion as provide answers.

I would urge that we stop “pastoral accommodations” that play to the Zeitgeist while offering limp lip service to principles we say Catholics “should” keep in mind (the uniqueness of Sunday or the penitential nature of Friday). The accommodation simply puts us on a slippery slope to undermining that principle.

We should stop making “pastoral accommodations” that, in the final analysis, put the canonical cart before the theological or liturgical horse. While the current pontificate is right to oppose “clericalism,” such “accommodations” are in fact just that. In the end, theology and liturgy are rendered inordinately subordinate to canon law and pastoral concerns.

If we are to think of the Saturday night Sunday Mass as somehow an extension of Sunday, then perhaps we need to think of it really in proximity to Sunday. In many dioceses, perhaps driven by lack of priests, Saturday night Masses are creeping earlier and earlier on Saturday afternoons, even to 3:30 or 4 pm. The earlier the Saturday “evening” Mass, the weaker the nexus to Sunday. My experience is that, in most dioceses, the “Saturday evening” Mass is almost always at 5 or 5:30 pm. Liturgy offices might want to encourage later Masses (which may have the effect of disclosing and challenging priorities, e.g., interfering with “going out on Saturday night”). Because these are not true “vigil” Masses, however, I hesitate to repeat the injunction Rome has normally applied to the Easter Vigil: that it occur after dark.

Finally, a renewed catechesis of Sunday is in order. The Church’s theological teachings on the unique status of Sunday is rowing against overwhelming cultural currents that ignore it. Our own liturgical scheduling in some sense abets those currents by turning Mass into an “obligation” to be stuck into the second half of the “weekend.” Yet our preaching and teaching about the Christian nature of Sunday is rarely heard.

An Excursus on Time

The French theologian and Archbishop of Cambrai, François Fénelon (1651-1715) observed that, in comparison to his other gifts, God is rather sparing on time. For an eternal God, all time is now; for us spatio-temporal humans, time is the context in which we must make choices and express priorities by his presence. The constant “pastoral” quest to “accommodate” demands on man’s time seems almost always to sacrifice the spiritual for the temporal, even though the physical needs no support to make its case.

The decision to treat Saturdays as Sundays for Mass purposes—like voluntary penance on Fridays, etc.—occurred in the context of a richer religious culture wherein its proponents could hope the Catholic tradition would survive. Half a century on, the truth is that the cultural signposts on which those “reformers” were depending are dramatically less prevalent, in part because the changes did not reckon with their own secularizing impact. In a modernity that values time perhaps even more than money, where one invests time speaks volumes of where one’s heart is (cf. Matthew 6:21).

The truth is we have reached a paradox. On the one hand, Sunday has practically ceased to be