SPACES OF EXPLORATION

I am a Bachelor of Architecture graduate from the Jindal School of Art and Architecture, O.P. Jindal Global University, Delhi-NCR, India.

Through my undergraduate period, pursuing an education in the built environment, I discovered my interests in questions concerning design, people, and culture, and performing explorations of their processes and practices to explore situated built environments inhabited at interior, architectural, and urban scales.

As a part of my coursework, I worked on various re/design and re/ development projects. Additionally, I have worked in a diverse set of organisations and fields, expanding my research and presentation skills, as well as my comprehension of, and engagement with the infinite world of design.

I work at (and beyond) the intersection of these areas of interest and explore alternative narrative and design exercises concerning built and urban environments.

UNDERSTAND THE COMPLEX COSMOLOGIES AND PROCESSES OF THE WORLD

INSTITUTION

CURIOSITY

OPPORTUNITY

AWARENESS

BODY OF THE SELF

EXPLOITATIONS

SENSIBILITIES

SENSITIVITIES

INTERVENE WITHIN SPECIFIC CONTEXTS TO FACILITATE DYNAMIC ENVIRONMENTS

INTENTIONALITY RESPONSIBILITIES

Curiosity, opportunity, and institutional support have privileged me to explore various facets of the world. I concentrate, through focused awareness and intentionality, on the threads of exploitation within it (diagnostician), and my responsibilities towards them (designer), as they pass through me. This portfolio captures some of these processes and is modest evidence of my explorations.

Noun. A desire to capture fleeting experiences, like envisioning life and wanting to press “pause”.

In his documentary/cinematic art film ‘Man with a Movie Camera’, Dziga Vertov represents an ordinary day in Russia in the 1920’s. Morii takes scenes from this film and re-arranges them within a video collage film to produce an alternate narrative about photography, and the desire to capture the moments in one’s life through a camera.

Morii highlights how film narratives can be re-produced through collaging existing material into newer narratives, exploring the arbitrary relation between visuals and their meaning, and how they are altered through sequential re-arrangement of film scenes from the constructed context of a film.

These films (as group projects) explored film-making as a method of storytelling by (1) collaging scenes from an existing film to create alternate narratives, and (2) showcasing the journey of exploring different methods of representation.

Noun. The realisation that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own.

Sonder illustrates the multiple methods through which a physical site (a small garden) is represented in an attempt to reject singular narratives. In the depiction of this process, the film critiques various forms of representation and the inadequacies that persist within the ‘accurate’ depiction of spaces. It also highlights the obsession with representation within the discipline of architecture.

As the students realise that none of the chosen methods of representation are able to ‘accurately’ depict the physical space with all its intricacies, layers, and meanings, they are forced to unlearn their preconceived notions on various forms of representation.

Traces of the sun fall on his face, through gaps in the curtains as they move forward and backward in the breeze. Entangled in a blanket, his legs were tied to one another, too tight to move. In rolling over to the other side, the tensions of the blanket fall apart. As he twists and turns, his body is at once, tense and relaxed. His disturbed ears tempt him out of bed, with the need to close the loud window. But he stays put, nothing a pillow over his head can’t solve.

They develop into habits, then forced into behaviour. Intensities of feelings, and sensations, are now instinct, almost reflex. He is tight, and soft, entangled in webs of comfort, discomfort, and of what lies outside it.

An hour passes by. The blanket now covers each and every inch of his body, the bottom of his feet tugging at its edges, trying to hold it over. The wind on his toes would be too cold, sending shivers up his legs. His arms wrap around a pillow, pressed tightly against his chest, for its freshness, but also its eventual warmth. The comfortable clothes he wore last night were now awkwardly folded, creased, lodged, and wrapped.

Complexities build up and dissolve at the same time. Flashes of memory, some clear, some forgotten; of dreams, some lucid, some nightmares.

This isn’t new, it’s old in fact - laying, for hours, on what is now a deflated mattress. With his head confidently placed on a fresh pillow, he stares at the fan, round and round, round and round. The power of its movement, it’s hypnotising swing, captivates him. He has lost all agency to think, to speak, to move, surrendering to a moving circle. He tries to count. But is it blades per revolution per minute? Or revolutions per minute per blade?

There is no motive, not one which can be understood at least. Emotion is almost lost but cannot. Alas, what can he, if not feel?

His eyelids shut once again. He cannot, and does not wish to, open them again. The world ceases to exist, just for a moment, just for some quiet. All memory is gone, all thought has stopped, just for that moment, just for some silence. They creep back in, bringing with them anxiety, anger, and bitterness. The night’s sleep has provided with it, comfort, energy, life. And sounds, even in insignificant volumes, now irritate him. It is hard to fall back asleep.

Constituents of the day, sounds, smells, tastes, pull him away from himself, disorienting, succumbing. His body is nettled with the push and pull of the everyday, brought back to life only with darkness, just for a moment, just for some silence.

His face is smothered in the uncomfortable contours of the (once) mattress, his chest flat, and toes hanging over the edge, swinging. Any form of movement reverts back to a cocoon, simultaneously comfortable and not. The need to escape, to get out, and to leave, emerges among puzzling intensities of thought, feeling and sensation. Perhaps on the fourth deliberation in his mind, his feet touch the bitter marble floor.

This creative non-fiction piece was inspired by Kathleen Stewart’s book - ‘Ordinary Affects’, which renders the affective environments that are generated in ordinary life by animating mundane circumstances through the poetics of language and landscapes.

VISUAL GRADIENT

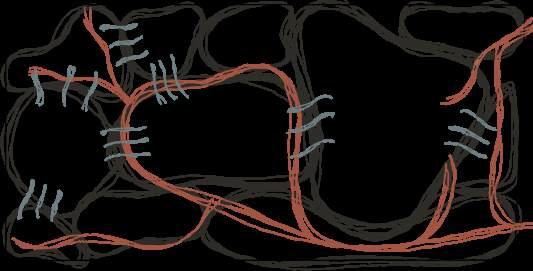

RE/PRODUCING BODIES MOVEMENT

RE/PRODUCED BODIES

Thelabouringbodydesires re/productionwithinMarx’s labour-value system, fuelled by the Freudian

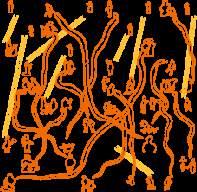

This project analyses a page (104) from the graphic novel - ‘Aranyaka: Book of the Forest’ (2019), authored by Amruta Patil and Devdutt Pattanaik. It explores the graphic illustrations as fields of knowledge production, creative exploration, and transformative world-building.

PANEL 1

PANEL 2

WEAVER CLOTH COLUMNS THREAD KATYAYANI FLOWERS/BUDS GROUND NUT PLANT SNAIL SHELLS SNAIL BODIES OF HARDNESS OF SOFTNESS

PANEL 3

1. IDENTIFICATION OF FIELD ELEMENTS

2. SUBJECTIVE CATEGORISATION OF ELEMENTS // BASED ON

A. TEXTURE AND TACTILITY

HARD ELEMENTS

SOFT ELEMENTS

MULTIPLICITIES // The categorisation into hard and soft is insufficient in describing identified elements, where descriptive words change based on the varied articulation of their tactile experience in Hindi.

B. TENSION AND TIGHTNESS

TIGHT ELEMENTS LOOSE ELEMENTS IN-BETWEEN

EXCEPTIONS // Specific elements (snail body- tense but fluid, and threadtaut through use) highlight how categories disintegrate when elements (in their inter-relationships) don’t exist in isolation but in changing contexts.

3. ANALYSIS OF TAXONOMICAL CATEGORIES

THE (DIS)ORDER OF THINGS - OF ABSURDITY AND TAXONOMY //

The limitations of taxonomy (of multiplicities beyond categorisation and lack of spaces for exceptions) highlight how ordering systems are informed by the biases, motivations, opportunities, and abilities of the individuals creating them.

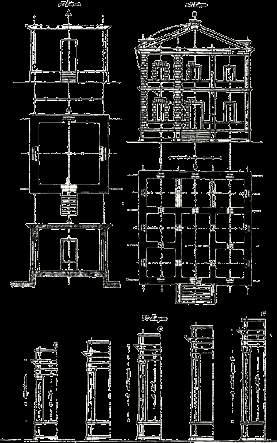

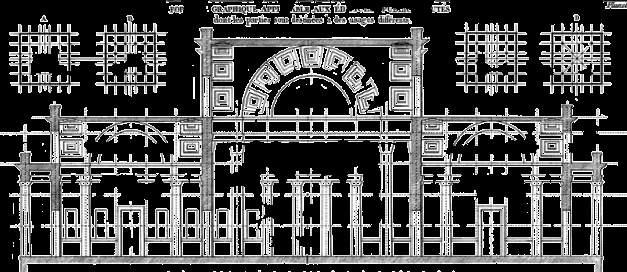

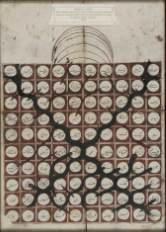

This academic poster is a visualisation of the arguments forwarded by Jean Nicolas Louis Durand (17601834), a notable figure in NeoClassicism and its architectural manifestations, which used simplified, repetitive, and modular elements. He propagated the true aim of architecture in its utilitarianism practice, deeming it to be a social necessity. He declared the beauty of architecture to be in its fitness and economy rather than its ornament.

Identification of elements and creation of types

Situatedness and context are important.

Emergence of certain GENERAL PRINCIPALS as a result of observation.

PLANS SECTIONS

ELEVATIONS

Visual Act.

Occurs within specific contexts.

SYSTEMATIZATION

ALLIANCES OF COMBINATIONS

Means employed to achieve the aims of architecture

OBJECTS AND ELEMENTS OF ARCHITECTURE

COMBINATION OF ELEMENTS (COMPOSITION)

TRUE AIM OF ARCHITECTURE DISPOSITIONS (ARCHITECTS CONCERNS)

Beauty (of grandeur, magnificence, variety, effect, character) as an inherent quality to buildings that are simple, fitting, and economical.

FITNESS

Solidity, Salubrity, Commodity

ECONOMY

Less costly, more harmonious

Happiness and protection of individuals and society.

SOCIAL UTILITY

Public Utility: Building at the least possible expense.

Private Utility: Building as fit as possible for a given sum.

Visual / Mental Act. Physical Act. Occurs within the Square Grid. Devoid of Context - Space of the Architect.

Occurs within specific contexts.

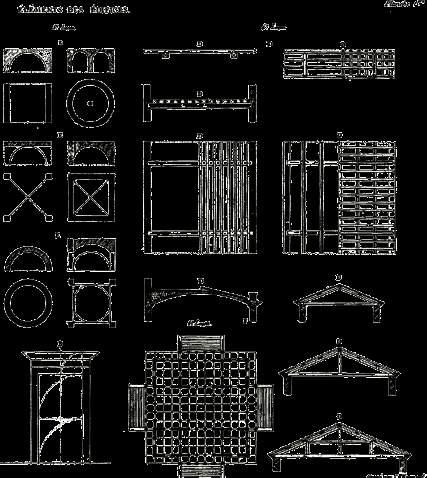

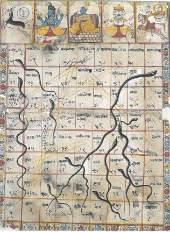

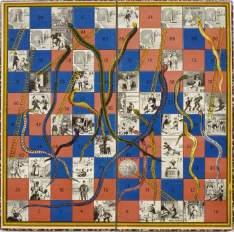

Traditional Indian board games have been inherently speculative in nature and rely on subjective participation and imagination, curating a strategic play within multiplayer modalities, sporing dialogue, debate, and discourse as forms of engagement in order to move across the board. These highly structural engagements are mirrored in the material, mental, and social ecologies that have produced these games.

Game boards perform as sites of pleasure, risk, leisure, intellectual interaction, and socialisation. Experiences are grounded in designed play through engagement with a series of rules, constraints, and possibilities to navigate these sites and reach a desired end.

This project closely examines the craft-cultures, political acumen, aesthetic agendas, and community making ambitions of society enmeshed on the sites of these board games. It projects the speculations born from the game worlds to their sites of production, transference, and participation to understand the game as the central artefact, producing worlds born from the logics and rules of the game.

This project diversifies the imagination of Indian histories from its religious, nationalist, and labour specific connotations. It documents a fascinating path, moving from Indo- to Indie-Futurisms, of decolonisation that is not subtractive but synthesising, to imagine futures from everyday imaginariums.

Within these games are present bubbling under-histories and latent Indie-futurisms, producing a conflated synchronicity of linear and cyclical time within the game-worlds. Participation in these worlds require a becoming subjectivity that is liberated from the teleological notion of time. Can this subjectivity be recreated outside game worlds? How can non-teleological worlds be generated outside their own sites of production? Are these processes transferable and transformable?

In ‘The Art of Play’, Andrew Topsfield provides historical references to render functional relationships between the cultural significance of board games, and their rules, players, and materialities. A set of actions and procedures constitute a layer atop these functional elements, identified through an exercise in worlding - of employing taxonomical classification to produce a criss-crossing of the material, affective, cognitive, emotive, and formal.

Working with game boards as sites of production, taxonomies allow an examination of the visual and material, specific elements within them, making processes, meaning histories, associative relationships, and the emerging narratives within the site of the board, forming meta-sites to locate under-histories and Indie-Futurisms.

VISUAL ELEMENTS

INDIVIDUAL IDENTITY

COLLECTIVE OR SUB-DIVIDABLE

MOBILITIES

PHYSICAL/SYMBOLIC MOVEMENT

PLAY ACTIONS

GESTURES AND ACTIVITIES

SPATIALITIES

SPACES, FORMS, AND MATERIALS

LOOK AND TEXTURE

ARRANGEMENTS AND ORGANISATION

AS SITE OF INDIEFUTURISMS

OF AFFECTIVE WORLD-BUILDING AND MULTIPLE IMAGINATIONS

This project (SOIF), funded by the Graham Foundation (2021), examines traditional Indian board games as sites of potential/production, in the search for latent Indie-Futurisms within them. I have worked on how taxonomies aid in deconstructing the historical archives of the game boards.

This Folding X (Curule) Chair is estimated to have been fabricated by an unknown furniture-maker in the northern regions of Netherlands in the 17th century.

TOTAL WEIGHT OF 11 KILOGRAMS

Armrests rise front to end in a sliding arch above the pillars, topped with small lion sculptures bearing shields, placed atop ionic capitals decorated rosettes.

Leather fabrics attached to main frame using moderately large copper nails. Creases visible in the centre of the leather fabrics indicates the foldable nature, making transportation easier.

MATERIALS AND MAKING

Folding X (Curule) Chair, Walnut Teak Leather, Copper, North Netherlands, c. 1620 - 1650, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Front legs decorated with deep relief carvings sculpted to display tendrils, underwater (dolphin-like) creatures, crowned Triton/merman on the left, and a naiad or water nymph on the right.

PRIMARY HARDWOOD

NAILS

SEATING / BACKREST

Front and rear pillars are hinged together as inverted semicircles (X-shaped). Hinge fitted with lion head in front.

Both pillars placed facing outwards to provide load-bearing capacity Connected on right side with a wooden piece with cutouts. Rear pillars glued using a veneer.

HISTORIES OF POWER

The origins of the Curule chair seat are traced back to ancient Roman and Egyptian empires, when it was popularly knows as the sella curulis (currus meaning chariot). According to Titus Livius (Livy), the sella curulis originated in Etruria, constituting regions within central Italy (c. 750 – 500 BC), and its form can be derived further back from the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570 – 1544 BC).

The curulis is prominently considered for their significance in being placed within the Roman courts and palaces. Recognised as a form of throne signifying political and military power, it was reserved for distinguished individuals that held imperium, governmental/military authority, the three flamines maiores (high priests of the Archaic Triad of major gods), and royalty that were recognised as allies by the Roman Empire (Weinstock, 1957).

They were traditionally constructed and veneered with ivory, with curved legs forming an X, low armrests and no backrests, and decorated elaborately with carving and ornament. Supposedly, the design and materiality of the chair was supposed to produce an uncomfortable sitting experience over a long period of time, a feature that would discourage prolonged discussion and deliberation (Rybezynski, 2017).

The Italian Renaissance (c. 1400 - 1600) saw the revival of ancient and historical objects/forms, introduced with new material constructions, techniques and processes (Dyer, 1919). One could trace the re-emergence of the Curule in several different regions of Europe in that period.

The form of the chair and use of ivory within it indicates a revival of traditional material practices, whereas more contemporary design practices and elements showcase an evolution of design - with advancements in technology, developments in craftspersonship, and requirements of the time, all within specific contexts of usage, class, hierarchies, and geography. The design iterations across Europe, evolve in their own cultural contexts, and highlight the movement of forms/materials across borders through cross-cultural exchanges of design practices and ideas by royalty, designers, crafts persons and other stakeholders.

The Curule chair forms an interesting example to understand the histories and evolution of the object within themes of power and hierarchies; movement of design practices and the cultural exchanges of design ideas, skill and materials; and the examining of specific material cultures and materialities, to study objects as storytellers or indicators of social, cultural and economic phenomena.

Hip-Joint Curule Armchair, Walnut, Ivory, Camel Bone, Silk Velvet, Spain, c. 1480 – 1500, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Neo Renaissance Curule Chair, Wood, Solid Walnut, Acanthus Leaves, Unknown Location, c. 1880, Selency, London, UK

Franco-Indian Curule Chair, Rosewood, Lotus Flowers, Pondicherry, India c. 19th Century, Private French Collection

This project presents the evolution of the Curule Chair (Sella Curulis) through a study of its historical importance, investigation into material/design forms, and tracing its iterations across geographies, positing the chair as a crucial indicator of social and cultural phenomena.

“…for it is in becoming memorial and monumental that a true perfection is attained...” - John Ruskin, The Lamp of Memory, 1849

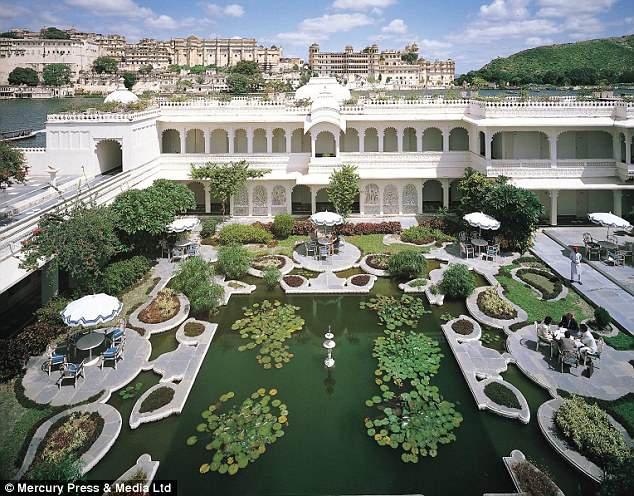

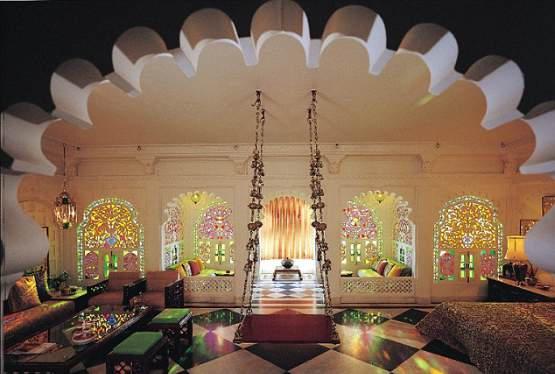

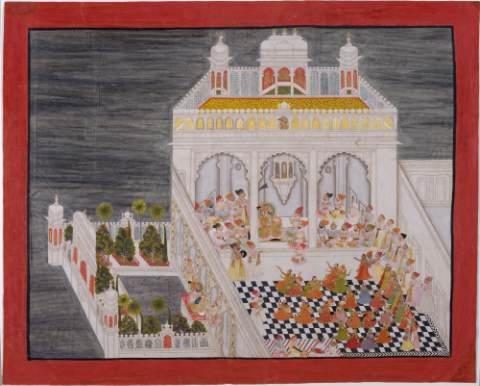

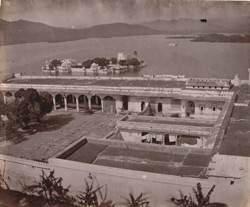

A calm serenity envelopes the atmosphere around the Jag Niwas Lake Palace in Udaipur, constructed by Maharana Jagat Singh II, the 62nd successor of the royal Sisodia dynasty of Mewar, in 1746. The dynasty’s power, wealth, and taste for finer luxuries is reflected in the construction of the Jag Niwas Palace which seems to float atop Lake Pichola, an artificial lake (originally created for carrying grain) named after the nearby Pichol village.

Source: Taj Hotels

Maharana Jagat Singh II was considered to be a descendent of Surya, the Hindu God of the Sun, and the East facing palace allowed its inhabitants to pray to the sun at dawn (Sehgal, 2009). Also visible from the East end of the palace is the City Palace along the lake shoreline. The lake, and the views from the palace, are bound in the South-West directions by the Aravalli mountain range, forming a majestic backdrop for it. Together with the older Jag Mandir Lake Garden Palace which stands further South from the palace, a strong ecology of rich cultural, religious, and architectural heritage is facilitated within Udaipur.

The built form of the palace and within Udaipur displays great “appreciation for the historic core as a cultural artefact with a deep connection to the water” (Samant, 2010). The lakes define the rich materiality of the landscape, reflecting the ardent relationship that the people share with water, and highlighting the crucial role of water in the dry and arid climate of the region, where practices of water harvesting and conservation have evolved over time into rich cultural practices (Samant, 2007).

The palace building is multitiered, with open pillared terraces, colonnades, and large and decadent courtyards lined with fountains, gardens, swimming pools, and lily ponds. The upper room is circular, and topped with a magnificent dome structure, built with twelve enormous slabs of marble. The floors and walls of the palace have been inlaid with black and white marble, then adorned with stucco moulding, coloured semiprecious stones, mosaic pattern work, and ornamented niches.

Maharana Ari Singh with Courtiers Being Entertained at the Jagniwas Water Palace; Ink, opaque watercolour, gold on paper; Bhima, Kesu Ram, Bhopa, Nathu (Artists); Udaipur; ca. 1767; Private Collection.

Maharana Jagat Singh II boating near Jagniwas, Udaipur; ca. 1746-50; Museum Rietberg, Zurich.

Historical photographs of the Jag Niwas Palace from 1882 taken by O.S. Baudesson for the Archaeological Survey of India Collections showcase the pavilions located within the palace, with their courtyards, gardens, and fountains. These photographs highlight the wondrous beauty of the palace, and its marble piazzas enclosing luxuriant orange gardens, sombre cypresses, towering palms, and gilded minarets.

Garden and pavilions filled with trees and vegetation in the Jag Niwas (Lake Palace) courtyards.

View across courtyards in City Palace looking towards Pichola Lake, with Jag Niwas (Lake Palace) in foreground.

General view of Jag Niwas (Lake Palace) and Lake Pichola, from the City Palace.

This project presents a biographical account of the Jag Niwas Lake Palace, Udaipur, and its context of construction, building materialities, histories of pleasure, and restoration processes, through an exploration of archival documents, historical photographs, miniature paintings, etc.

“The earth is the very quintessence of the human condition.”

- Hannah Arendt

Protest camps have been written about as ‘third spaces’ which gather people together around a particular cause or issue. Camps are seen in their impermanence and continuities, suggesting new forms of life and living, survival based on patience, temperance and struggle. A lot of literature on refugee camps explains them in relation to legitimate spaces, or the manners in which people inhabiting camps navigate permanent and structural discriminations and delegitimization. This essay presents a protest camp, now running in its eighth month at the borders of Delhi, through a taxonomy of its material forms and materialities that generate its built environment. Here, the materiality of the protest camp produces timelines, events, surfaces, mediums, labors, intensities and continuities of the camp site. The materiality of the protest is both its evidence and its existence.

In her work ‘The Human Condition’, Hannah Arendt speaks of the idea that being able to live in a polis was to be determined by words and not by violence. If one were to imagine Arendt’s ideas at the protest site emerging at the Delhi borders, one would extend this site as a form of a polis, primarily determined by its materiality, and its form. The Arendtian notion of making, fabricating, and building merge with the materialities of this protest site, which has continued with people living on a highway for the past eight months.

September 2020 witnessed the introduction of three new farm bills by the central administration. These farming reforms would relax regulations on private entities in the agricultural market, a move that angered farmers across the nation. Their demands constituted a repeal of the unjustified reforms that fragment and deregulate the market along with a legal guarantee on the minimum support prices for their produce. After protesting for a few months at state and province levels, farmers from Punjab and Haryana (northern provinces located near the national capital) started their journey to Delhi in November. The farmers utilized methods of gherao (surrounding), road blocking, and dharna (demonstrations) across the borders of Delhi. Having traveled till the national capital’s borders (Singhu, Tikri, Ghazipur), they eventually set up campsites as their vehicles were halted from entering the city. The protest site began with them stopping their vehicles on the highway. The mode of transport to reach the city became the elementary material on which the protest continues to stand today.

The protest at the Singhu border extends for about ten kilometres on the highway connecting to the Delhi border. A stark difference of material forms encounters us as we walk across the barricading by the Delhi Police into the protest site. Harsh concrete, metal, and barbed wire of the State barricading moves into a differential materiality as we enter the site. Albeit built upon tractors and farmers’ trolleys, the campsite softens into providing us a distinct affective milieu of objects, machines, and materials generating animate life worlds of the protesters. Living and cooking spaces form the centrality of the protest, which functions as a public kitchen for the protesters at the site. This continuum and presence of life, with the reminder of food, kitchens, and uninterrupted cooking, fuel the central infrastructure of dissent here.

Unlike many other protests across the world, where people walk in rallies or emerge at a particular site only to disperse at the end of the day, the protest site at Singhu border is a live-in, a constant location of making, and a labor of love. The highway transforms into a new surface of materialities and acts of work, labor and action through the development of this protest. New forms of dwelling, settling, circulating then emerge to endure the protest against an unrelenting government. The criticality of this protest site is its continuity over harsh winter, intense summers, and monsoons, yet affords a sense of the familial, grafts survival through ordinary materialities, and feels like home. A series of parked farmers’ trolleys, tractors, and trucks form the length of the protest, inhabiting rooms, beds, places of rest, kitchens, and courtyards. We attempt to unpack both the material and the built forms that these provide to the site.

Refer to full essay for a detailed inquiry of material forms and environments.

This ethnographic work presents the materialities of farmers’ protest camps on the borders of New Delhi (2020-21) through a taxonomy of its material forms and built environments. This essay has been co-authored with Prof. Sarover Zaidi (JSAA) and was published in ‘The Funambulist’ Correspondents Editorial in 2021. All images by Sarover Zaidi.

This project maps life between buildings through experiences and observations of walking in the city through a description of spatial configurations, architectural elements, objects, urban furniture, memories, sensorial (smell, taste, sound, touch, sight) and material forms, and everyday activities on the streets and neighbourhoods of Bengaluru.

I would walk out the front gate of my house on sunny afternoons and head left, towards Diamond District, a mundane apartment complex. Upon turning, I would encounter on the street, a pack of stray dogs resting on the uneven bumps where gravel had conveniently been injected into potholes.

After a few turns, I’d encounter a ‘nala’ (sewer) running under a narrow bridge. As the rotten smell would reach me, I would attempt to accelerate my pace. However, it was difficult to overtake people due to the risk of getting hit by a car on the narrow street, where the speed of moving traffic was quite fast, as it connected two large main roads. Having crossed the bridge, I would pass by fruit stalls, milk booths, and hawkers on both sides of the road on my way to the main road.

There were two ways to cross Old Airport Road (a busy major road), either through a foot-over bridge (which required going up four flights of stairs, walking across, and coming down the same number of steps), or waiting for the red light, walking across half the road, and waiting again at the median for the vehicles to come to a halt before walking across. I usually preferred the second option; given that it was usually much faster and going up and down stairs seemed too energy intensive.

After crossing the main road, I would then walk across the cars and scooters lined up at the mouth of the intersection, often crossing the designated line, and positioned in a zig-zag manner. I would move in front of one car, then behind a scooter, in front of another scooter, and so on.

The journey continued on a service lane running parallel to the main road. First, I would encounter a locksmith with hundreds of locks and keys framing his position in a shed-like structure. I never paid attention to him, and always assumed he was using soap to duplicate keys for people who lived far away.

On the opposite side, at and around a ‘panwaari’ (paan shop), bus drivers would be scattered around cement and stone slabs that were placed to replicate benches, smoking, drinking tea, and eating samosas. With buses always parked on this street, the assembly of drivers was justified. A public toilet, indicated strongly by the urine smell engulfing that area, and the Kannada equivalent of ‘sulabh shauchalaya’ (public toilet) written on a signboard below the English version, was my final encounter before disappearing into a canopy forest for about three minutes.

A footpath soon appeared on the left, adjoining a garden (separating the service lane from the main road), running along the street, carefully curated and maintained daily. I’d often see an old woman and a gardener, hired by the local municipality, watering the grass and trimming the hedges. On the other side of the street, a short boundary wall enclosed a very large, irksome, and desolate building, with its facade made entirely of a dark and shiny glass, reflecting sunlight directly into my eyes.

The long and straight lane terminated quite strangely under a flyover, into an ecosystem of people and their informally designated flows – an auto-stand on the side of the main road and an Uber pick-up on the other. The concrete footpath in between expanded in size, was lined with street food stalls, a technician repairing bicycles, and pedestrians scattered around. All kinds of people came together here – those waiting for taxis to reach the nearest hair salon, groups of teenagers coming out of auto-rickshaws after a long day of school, and suited men and women enjoying peanuts in newspaper cones. It became a place of congregation, for the shade it provided from the sun, and very commonly during monsoons, as shelter from the rain.

Having crossed this area, I would reach a broken footpath along the main road, eventually leading me to Diamond District (whose boundary ran along the main road) in an awkward and frustrating journey. The sewer from earlier would emerge once again on the right side, with a thin metal fence placed as barricading. And as the footpath would end abruptly, I’d reach my final destination.

As we leave the campus at night, we notice that lights from the university illuminate the intersection moderately well. Making our way through a turbulent crowd, we encounter cars, trucks, motorbikes, scooters, and other forms of transport on the highway. Fast moving traffic usually slows down at the busy intersection, but vehicles often make their way through it without reducing their speed and honking the entire way if the intersection seems even slightly devoid of commotion. With some effort, we manage to cross the highway at this intersection, often holding out our hands signalling to the trucks approaching rather quickly with their blinding headlights. As we cross, we hear the whizz of heavy vehicles pass behind us, making us jump ahead to protect ourselves from a perceived danger.

The sun casts shadows of trees on the roads, with their shapes and sizes dependent on the time of day and the position of the sun. When walking along the highway during the day, we jump into these shadows and remain within them, protected from the heat of the sun (even if it is in parts and for a few moments), and from the vehicles that zoom past us. With no pedestrian infrastructural provisions, the highway pushes us to its sides, making way for the fast-moving vehicles to claim the space – facilitated by their speeds and sounds. We succumb to this effort, and move into the shadows, where our unbelonging is proposed by an amplifying insect noise instead of speeding automobiles. We gauge based on sounds of vehicles and the irritation caused by their headlights – their position, speed, and when we will need to move further aside to accommodate them.

The nights challenge us further, owing to the lack of street lighting. We avoid shadow spaces under the trees, ones we leapt into during the day, preferring to stay visible. The torches on our phones light up the road, preventing us from stepping into excreta, or falling into a ditch. The challenge remains, we must stay away from the vehicles, but also the shadows. We find that a thin line traces the route of our journey, with sufficient space on either side to not compromise on safety. The speed of the lights and sounds impacts the comfort of our experience, and our perceptions of safety. The sound of the fast-moving traffic indicates an unpredictability, which is added to its unfamiliarity.

Whether day or night, there is a certain ‘quietness’ to the highway, where ambient sounds (of the wind, insects, and even birds) are supplemented with the frequent unsettling sounds of the passing of trucks, their Haryanvi beats, and their vibrations that enter through our feet and make their way up. As we approach our destination, there is some comfort in the familiarity of the stimuli we begin to perceive. Our eyes begin to situate boards, lights, chairs, and our ears discern from a herd of crowded exchanges and clicking of lighters conversations about chicken steamed momos, needing a break from work, and places one could proceed to afterwards for a beverage.

This film, made in collaboration with my classmate Anamika Sarker, explored the parallel narration of lights and sounds in the built environment by examining their impact on the sensorial experience of walking on a highway in Sonepat, Haryana.

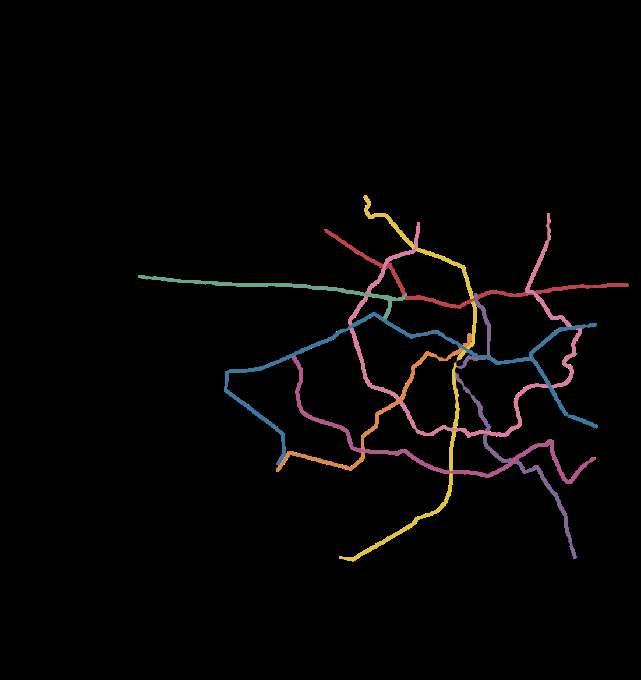

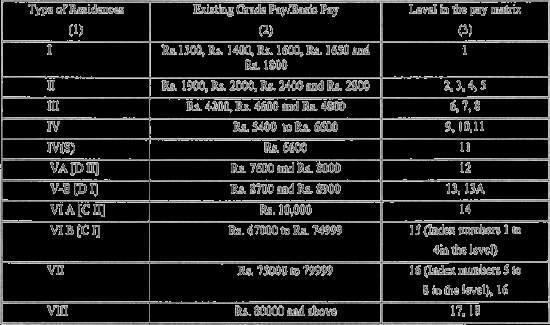

GPRA housing colonies are residential accommodations provided by the Central Government under the administrative control of the Directorate of Estates in Delhi (and 39 other cities), where all Central Government employees and employees working under the Government of NCT of Delhi (working in offices and specifically declared eligible for General Pool) are entitled for allotment of housing.

The allotment of housing within the GPRA framework is governed as per the provisions of the – Central Government General Pool Residential Accommodation (CGGPRA) Rules, 2017, and additional executive instructions issued over time. GPRA housing has been classified into 11 categories (excluding Hostels) as per Rule 8 of the CGGPRA Rules, 2017.

This has been done in reference to the level in the pay matrix drawn by the applicant in the post they hold in the Government of India, with Types I to IV as lower types of accommodation, and Types IV (Special) to VIII as higher types of accommodation.

As of 2020, there are 207 GPRA colonies within several different neighbourhoods in New Delhi, with the number of dwelling units within them ranging from 1 (at various locations) to 11,992 (in RK Puram) with the total number of dwelling units adding up to 70,578 across the entire city.

Although GPRA colonies across the city have been organised with varying arrangements, there are a few typical configurations that emerge within several of these colonies, depending upon the various Types of accommodation present within them. The GPRA colony in Chanakyapuri consists of C2 (VI-A), D1 (V-B), and D2 (V-A) dwelling units arranged along Satya Marg, Madhu Limaye Marg and Vinay Marg. Although not formally enclosed with boundary walls, the entry and exit points into these colonies have security/police barricades controlling the flow of traffic within them.

COLONY, CHANAKYAPURI

The type of accommodation provided within the GPRA framework is based on the living area of the dwelling unit (DU), which ranges from (<)30 to 522 square meters. The services and amenities provided with the housing is also determined by the type of accommodation. In the GPRA colony in Chanakyapuri, there are multiple dwelling units within a singular constructed unit, with two larger units on the ground floor with separate entrances, and smaller apartments on the first floor with a common staircase for accessing.

D1/D2 Flats

C2 Flats

S.O. Flats

The two larger units have front and back yards with green areas, paved side yards, with spaces for parking and other recreational activities for its residents.

This project explored the interplay of inhabitation and institution through a study of GPRA housing system in relation to the working of the Delhi Urban Art Commission (DUAC).

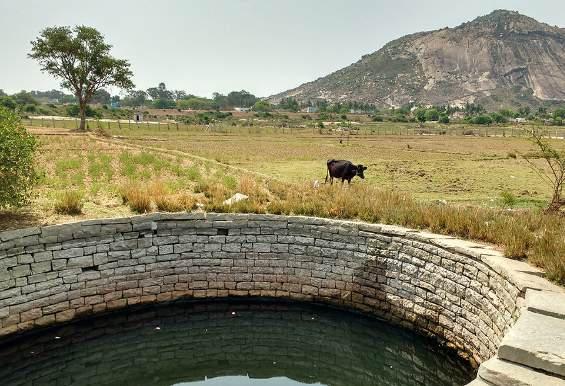

Less than 10% of rain-water percolates into aquifers based on hydrology, brought down to 1% with land ‘crusting’ due to urbanisation, where rain chokes sewers as surface runoff, inundating low-lying areas. The aim is to increase percolation to 60%, to meet the water requirements.

A Million Wells for Bengaluru was launched by Biome Environmental Trust, a not-for-profit organisation led by water conservation expert Vishwanath Srikantaiah. This movement aims for 1 million functioning open recharge wells in the city allowing for the recharge of shallow aquifers through rainwater harvesting, and raising the water table. A majority of water supplied to the city is pumped up 300m from the Cauvery River (flowing 100km south of the city), in an energy intensive process, and bore-wells (or narrow boreholes) that exploit and drain lower aquifers. The movement aims to resolve these issues of water supply.

The movements aims to raise awareness about the role of local communities in reviving open recharge wells through collective citizen action, and to provide/secure livelihoods for the native well digging Mannu Vaddar community who posses the knowledge of the region’s hydro-geology.

Open recharge wells mitigate erratic rainfall patterns and urban flooding, as well as reduce carbon emissions and energy consumption (by 20 times) through mimicking natural percolation patterns and routing rain-water back into the shallow aquifers instead of allowing it to flood.

Refer to the full essay for a detailed inquiry into active stakeholders, critical points, process replicability, broader change, and sustainable forms of development within the movement.

This project was submitted for the Occupy Climate Change! Movement which explores how urban communities respond to the climate crisis by investigating insurgent citizenship practices. Information from interview with, and images by, S. Vishwanath.

Gas and Electrical

Recycled

•Stiffened panels

•Remaining rerollable steels

•Irrepairable engines, pumps and pipes

Repaired

•Main and auxiliary engines

•Pumps

•Equipment

Reused

•Steel plates and sections

•Stiffened panels

•Pipes, etc.

HULL Structural Failure

OIL SPILLAGE Accidents

ENGINES Fuel/Human Error

MARITIME POLLUTION

AIR POLLUTION

SOIL CONTAMINATION

Ship design decisions must be reconsidered based on the parameters of safety, economy and environment. The ship recycling processes must be altered to extract the maximum from the existing materials and offer adaptive reuse solutions to equipment procured from dismantled ships.

By virtue of conducive tidal conditions that enable the cost effective beaching technique of dismantling in addition to lower manpower cost and lack of stringent regulations, South Asian countries offer solace to Europe and America’s expensive dismantling woes.

90,000 3,000

Vessels in world wide fleet of ships Ships dismantled every year

Avg. life of ships

50MN Workers

140 Countries 20-25 Years

29MN+ Tonnage of garbage produced by ship breaking in Asian countries as of 2013

LDT STEEL

(Light Displacement Tonnage) Melting Steel

ReRollable Steel

GADANI, PAKISTAN

85% Of Ship Breaking Yards Are Located In South Asia

CHITTAGONG, BANGLADESH

SINGAPORE

Ships recycled globally

Vessels dismantled annually

Workers involved directly

Involved in related fields

This research and awareness project aims to understand networked ecologies of un/sustainable development, environmental impacts on ecosystems, and human/community health factors of and within the ship demolition industry in India.

Security is a paradigm of governing that is softer and more liberal than a facially coercive form of juridical or disciplinary power.

Section 144 of the Indian Criminal Procedure Code, 1973, is a colonial era law which disallows the gathering of four or more people in a public setting when invoked, a law framed through a mechanism of security as explained by Michel Foucault in its modalities of power and procedurelegal code, disciplinary mechanisms, and security dispositifs.

LEGAL CODE // Involves laying down laws and fixing of punishments for those who break them

A binary division is created between permitted and prohibited (declared illegal and punishable) actions, based on social and cultural acceptability.

DISCIPLINARY MECHANISMS AND ACTIONS // Involves surveillance and corrective disciplinary action to prevent criminal activity

There are disciplinary actions aligned with principles of classical criminology that prevent illegal actions through a public display of harsh punishment, highlighting dangers of being caught.

SECURITY DISPOSITIFS // Involves dealing with probable events and optimisation of behaviours

The population is treated as a collection of bodies with physiological needs, where the State formulates and predicts patterns of movement within the given territory by -

ENUMERATING CITIZENS

DIRECTING ACTIONS

The invocations of Section 144 reflect a colonial heritage within the Indian criminal justice system and highlight the command of political directives in governing the ‘independent’ judicial structures of the State through the carceral forms of control exercised on bodies.

Dispositifs of security act on populations, manifesting itself across physical spaces, technologies, and temporalities.

Security relies on bio-power by utilising statistical analysis to prevent socially unacceptable acts and achieve economic equilibrium through population regulation by optimisation of birth/mortality rates, health/welfare statistics, etc. It consists of regulatory mechanisms with power relations intrinsic to the formation, implementation, and interaction of laws with populations.

Section 144 regulations comprise of powers conferred upon magistrates to issue orders that prevent and address any adverse impacts on human health, safety and public tranquillity within urgent ‘apprehended dangers’ that may arise in their territorial jurisdiction.

For a State, its population represents a field of governmental intervention dependant on variables created and modified by the government. Crowds escape this logic to perform as threatening and subversive social entities making it essential for the State to regulate their circulation. Section 144 is reflective of policy that controls and prevents subversive actions of crowds.

Through bio-political surveilling technology, an enumerative identity of the population is created and recorded. These technologies are utilized to maximise and duplicate good circulation and decrease bad mobility by continuously identifying and excluding threats or potential danger through disciplinary logics of temporality.

Security dispositifs aim at what has not yet happened, through systems of probability estimations. Owing to the technologies of security, its invocation is justified, and the contingency of a threat is rationalised through the logics of pre-emption, precaution, and preparedness that counteract identified threats before they materialise into damage or disturbance. Section 144 is one such sanctioned intervention that addresses safety concerns caused by such ‘apprehended danger’.

This project analyses Section 144 of the Indian Criminal Procedure Code, 1973, through Michel Foucault’s explication of security and power. Image by Ravi Sharma on Unsplash.

Arising out of 'Built Environments and its Histories' (Spring 2020), this zine examines ways in which inhabitants of cities transact spaces while engaging with interior-exterior / private-public binaries. My spread titled 'Cities, incomes, legitimacy', attempts to visually represent the 'unorganised’ and 'informal' forms of employment which contribute to the fabric of the city, and thus questions the validity of official documents in legitimising forms of livelihood in cities.

This project focused on luxury interior and services design for a penthouse apartment, developed by Supertech, in Greater Noida. The design dealt with built-in interiors, materials and furniture layouts, and services (including HVAC, plumbing, electrical, and automation) for a large terrace balcony, gym, living, dining, and powder rooms.

TERRACE (W/ PLUNGE POOL) // 1

LIVING ROOM (W/ BAR AREA) // 3 GYM // 2

POWDER ROOM // 4

DINING ROOM // 5

1.

TERRACE // 1

TERRACE // 2

DINING // 2 DINING // 1

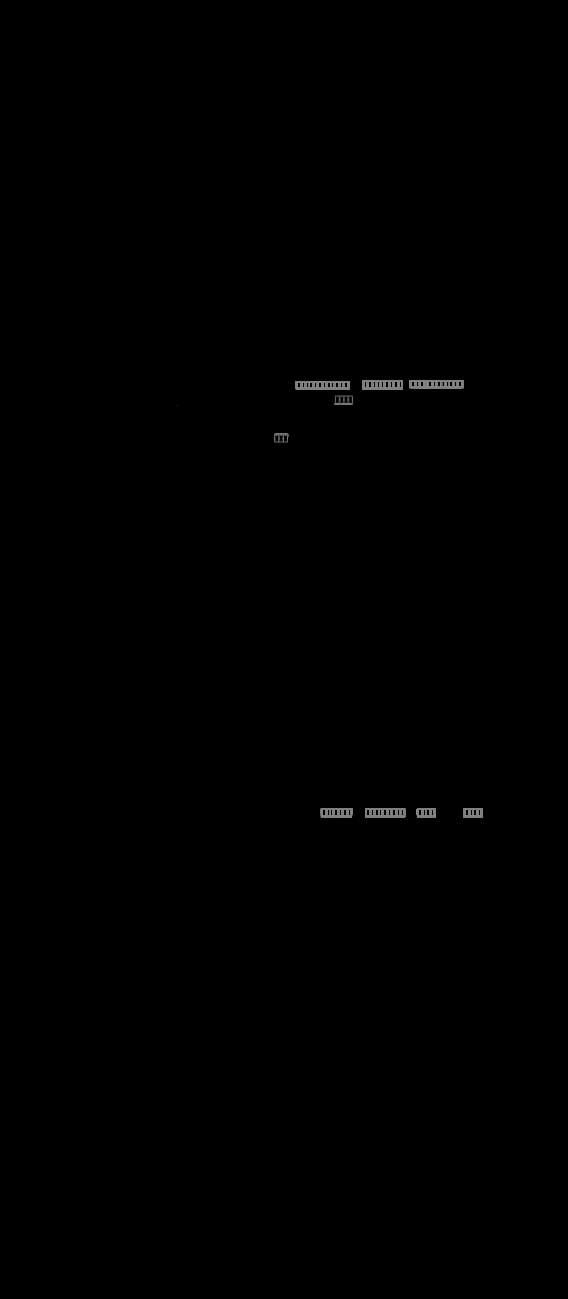

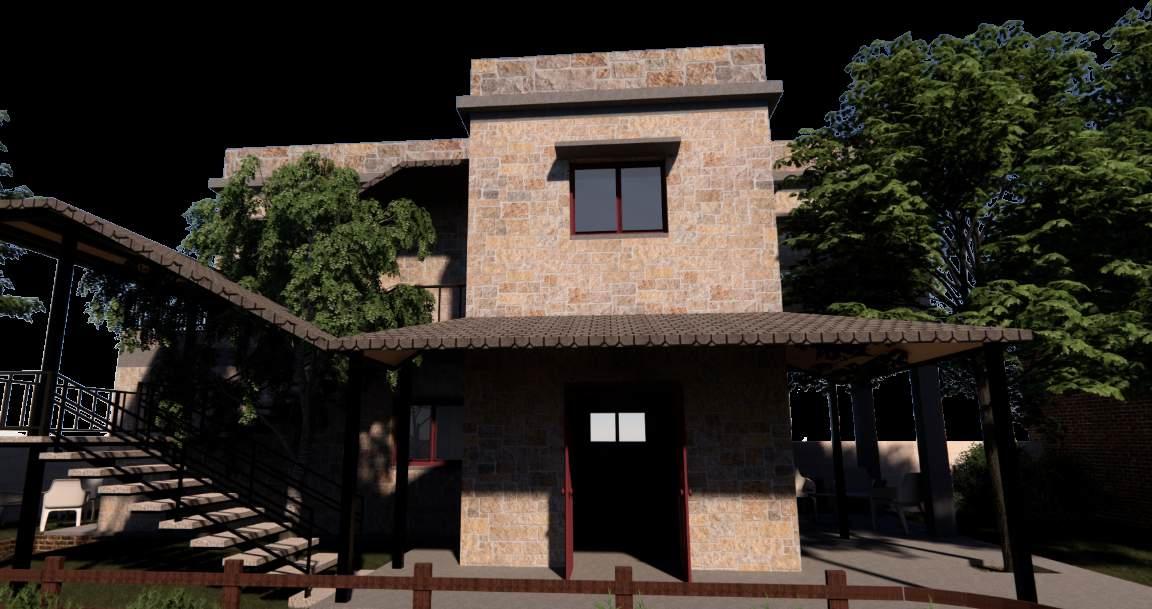

This project focused on the architectural form and space layout design of a banquet hall and quick service restaurant (QSR) combination in Bisrakh-Jalalpur, Greater Noida. The design dealt with structural design and form, in relations to interior and furniture layouts for banquet halls, reception and corridor spaces, offices, guest lodging, ancillary staff spaces, restaurant, commercial kitchens, exterior lawns, and parking.

The floor layouts were based on the activity programming of the business model prepared in the pre-design phase, trying to experiment with the potential of types of banquet halls (indoor, outdoor, and combination), and in relation to other spaces with a pre-function lobby as mediating spaces.

RECEPTION LOBBY // 1 RECREATION ROOM // 1

RECEPTION LOBBY // 2

LODGING // 1

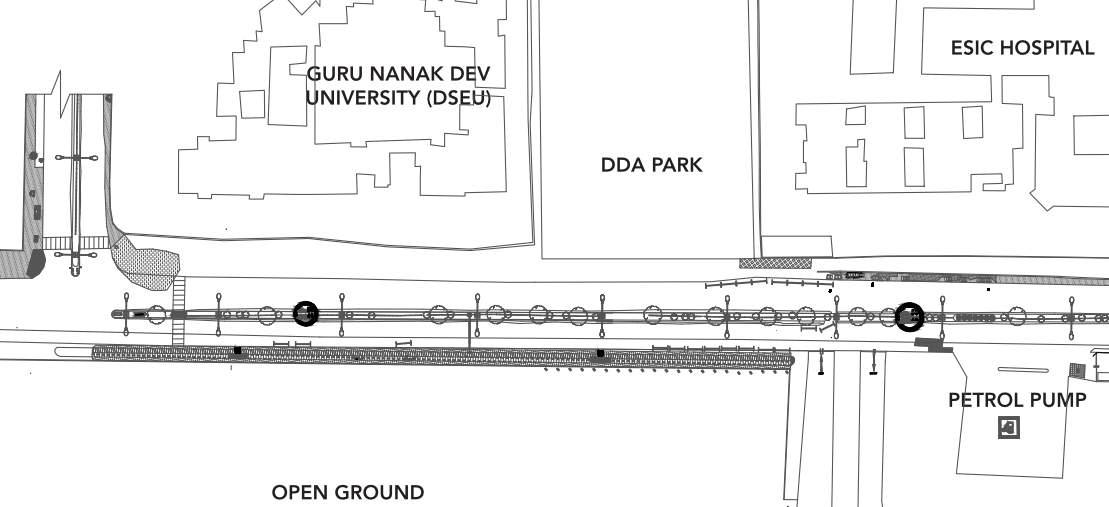

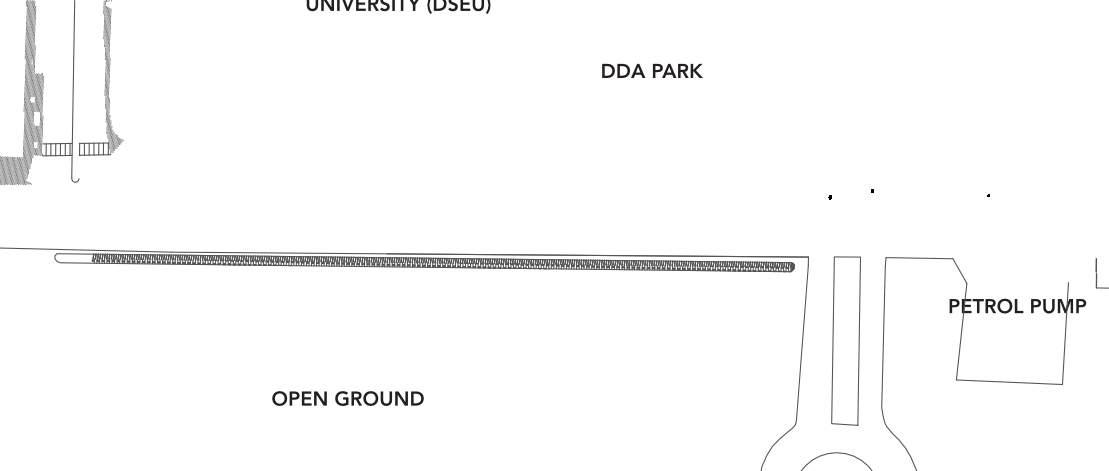

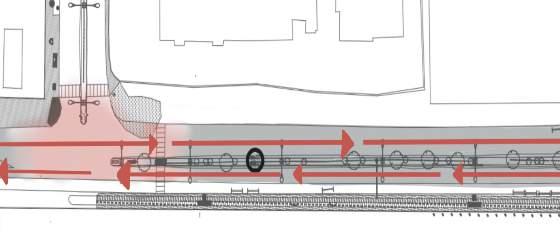

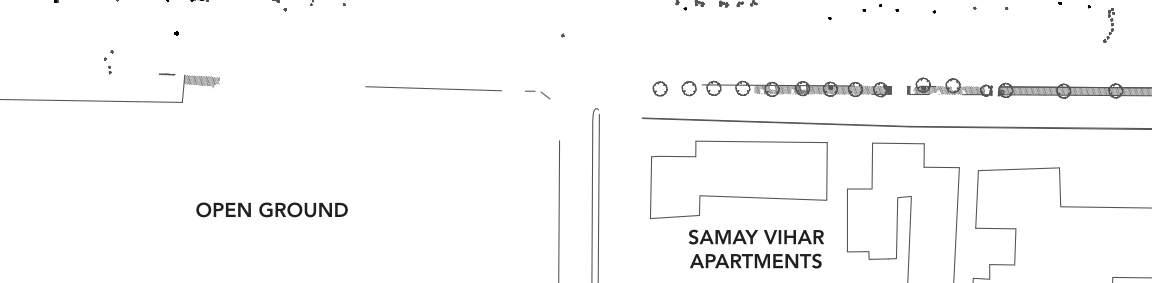

DR. K.N. Katju Marg is a sub-arterial road in Rohini, New Delhi (North), diverging into residential and commercial pockets, interspersed with public and private schools, markets, and gardens.

TOTAL LENGTH OF ENTIRE STRETCH:

LENGTH OF OBSERVED SEGMENT (S1):

KEY LANDMARKS ALONG SEGMENT:

Sachdeva Public School, ESIC Government Hospital and Residential Colony, TATA Power Grid, Event Gardens, Guru Nanak Dev University (DSEU)

// High speeding due to long and continuous stretches on the carriage-way without any enforcement or regulatory (traffic calming) measures

// Safety concerns with pedestrian movement and crossings due to clashing speeds, scales, and sizes

// Breaks in flow of pedestrian, cyclist, and vehicular movement due to crowding, broken footpaths, hawker ‘encroachment’, and congestion on roads

// Lack of NMV infrastructure forcing cyclists onto footpaths and wrong-side roads

// High footfall (pedestrians, auto-rickshaws, E-rickshaws) and movement at hospital entry/exit, bus stops, hawker spaces

// Homeless squatters on the footpaths and lack of basic civic amenities (rest areas, washrooms)

The client requirements for the building to be constructed on site consisted of -

HOME-STAY FOR TOURISTS AND BACKPACKERS

High paying urban tourists (private rooms) and backpackers (dormitories and tents) - as base for tourist activities

RESEARCH STATION & WRITERS RETREAT

As a base for researchers, writers, etc. who wish to stay for a longer duration of time

HOSPITALITY VOCATIONAL STUDY HUB

For training in hospitality and tourism of the local community members and graduates of the Adarshila School

// SITE ZONING // PROPOSED SITE PLAN

// RENDERED SITE PLAN

HOME-STAY // 1

HOME-STAY // 2

HOME-STAY // 4 HOME-STAY // 3

CENTRAL ACCESS

SEPARATION OF UNITS

CLIMATE ADAPTATION

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

INCREMENTAL BUILDING

PRIVATE WORK-STATIONS

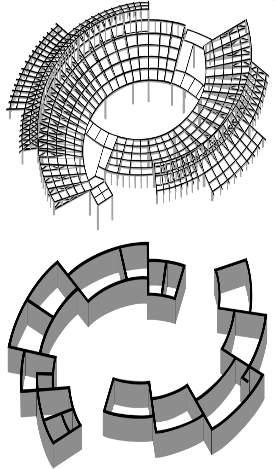

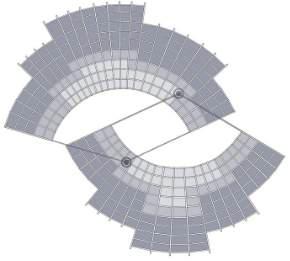

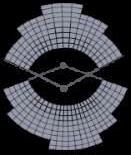

Located in the Casamance region of Southern Senegal, the Monsoon Primary School is inspired by the practices of inhabitation, cultivation, and conservation of local communities. Borrowing from Tolou Keur, the drought-resistant circular gardening technique employed by the farmers, and the houses of Senegal, the school emulates a similar radial form. The construction is characterised by the use of reinforced earth bag walls, plastered with mud. The roofing system is crafted with woven plastic mats lined on a bamboo framework. The open central courtyard embodies the spirit of communal learning, and provides space for children to gather, play, perform, and inhabit in their own ways.