Rewriting Landscapes

Rewriting Landscapes brings together leading contemporary Aboriginal artists who reclaim and reframe the genre of landscape art through photography, sound, and video.

For generations, colonial representations of landscape have framed Country as empty, passive, and picturesque. This was not accidental: the making of canonical Australian paintings served a complex of wider social forces which positioned the ‘landscape’ as an object to be viewed, owned and exploited.

The artists in this exhibition disrupt that gaze. Their works assert presence and continuity, connection – and critique. Overwriting settler descriptions of their own and other people’s Country, sometimes directly referencing landscape traditions, they produce new visual understandings through the lens of First Nations experience.

Using audiovisual and photographic techniques, they bring contemporary tools to the task of dismantling colonial tropes, reimagining the landscape not as a neutral backdrop, but as a subject. Country, as this subject, represents a complex and all-encompassing ancestral and metaphysical system; sentient, storied, and sovereign.

Queering the landscape of art history

Troy-Anthony Baylis and r e a

Two works by Jawoyn artist Troy-Anthony Baylis frame the visitor’s first experience of Rewriting Landscapes: Making Camp at ‘Forest, Cunningham’s Gap, 1856’ (2009) and (pink)Poles (2005-6). Baylis’s career, working across assemblage, painting, textiles, performance and photography, is marked by a commitment to unsettling colonial imagery. Making Camp at ‘Forest, Cunningham’s Gap, 1856’, is part of his landmark 2009 Making Camp collage series in which the artist physically and symbolically intruded on the colonial landscapes of canonical painters Glover, Johnstone and Martens, playfully imposing his drag alter-ego Kaboobie, along with photographs of works from his (pink) Poles series, onto the paintings. Making Camp at ‘Forest, Cunningham’s Gap, 1856’ is thus highly deliberate, strategic Aboriginal intervention into the foundations of Australian art history. This artwork begins with a colonial source image - a mid-nineteenth-century painting of a Queensland landscape by prominent colonial artist Conrad Martens. Martens’ images of the Australian bush, composed in the European picturesque style, were instrumental in domesticating the rugged Australian environment, erasing the sovereign Aboriginal presence and (re)framing the land as passive property for encroaching settlers. Martens used the European “Claudian formula’ of landscape composition, which highlights the subject with a dark foreground, light middle-ground and framing trees, to make the Australian wilderness visually intelligible, knowable and controllable to the painting’s (British) audience, a process art historian Marcus Clarke later described as domesticating a “primitive” and “frightening” landscape. Like others of the era, Martens’ work was a tool of visual possession, documenting, stabilising and normalising the white presence, preparing the land for development and pastoralism, across various acts of “making camp” in a newly “claimed” land.

In an example of Baylis’ renowned wordplay, “making camp” not only refers to the settler act of establishing a presence seen in the original painting, but also to the functions of “camp” as a political tool for queer communities, where heightened theatricality, exaggeration, artifice and irony are strategically deployed to subvert social norms and create solidarity. Here, the artist makes the colonial artwork camp by manually inserting his drag persona, Kaboobie,

directly into the otherwise austere scene of Martens’ Claudian landscape - literally demanding entry to the canon. Kaboobie writes, “I rejoice in imaginings and I enjoy those visions of Australian second-settlement landscape that I render and occupy. In Making Camp at ‘Forest, Cunningham’s Gap, 1856’ 2009, with my kangaroo features and multiple meeting-place dress, I am enjoying a wander through the wilderness, wondering where to camp next and when to reach for what is concealed in my pouch”.

Adjacent to Making Camp at ‘Forest, Cunningham’s Gap, 1856’ 2009 is another work of Baylis’, from his (pink)Poles series of soft sculptures: three magenta knitted structures which project a commanding vertical presence in the highceilinged ACE gallery. Baylis’ (pink)Pole series (2006-2007) reference ‘burial poles’ that have a pre-colonial history and are a continued tradition in several Aboriginal and Pacific Islander nations. Some burial poles are open at both ends, while others are not, while some include the remains and/or belongings of the deceased persons they are representing. Through this orientation, the works represent death, specifically of Queer-Aboriginal bodies and culture that are not recognised and not represented. The hollow forms, open at both ends, lend themselves metaphorically to the queer trope of open-endedness. When the works are displayed, they suggest a ceremony of mourning; as Baylis suggests, “perhaps a monument to death and survival. Maybe they are conversing queerly with the 1988 installation The Aboriginal Memorial that comprises 200 hollow log coffins created by 43 artists from Ramingining and Central Arnhem Land, which remains on permanent display at the National Gallery of Australia.”

For the artist, making the work was a performance of grief and mourning, enacted by knitting round and around with great repetition until each object reached its chosen size. They were produced in various sites in Australia, but also in France, Germany, Canada, and The Netherlands, through a process the artist describes as a ‘migratory studio practice’. For Baylis, “just as an Aboriginal artist does not have to be on Country to create art of authenticity, neither do they need to be on Country to be in their spirit to be able to mourn. These objects appear disembodied because they are not solid objects; yet they also represent bodies, always present in history and remembered metaphorically through the objects that have been produced.”

Gamilaraay Wailwan and Biripi artist, curator, research and activist r e a’s artworks in Rewriting Landscapes, PolesApart and GARI, also frame the exhibition and reframe the landscape through queer Aboriginal eyes. Initially rising to prominence for groundbreaking experimental digital and video works such as PolesApart, their recent practice has expanded beyond new media, focusing on cultural reclamation through the exploration of installation, painting and text-based artwork. r e a’s research-led practice, which is deeply informed by lived experience as well as academic research, confronts historical erasure and the persistent impact of intergenerational trauma.

Their influential 2009 PolesApart video, included in the NSW high school curriculum but rarely seen in South Australia, plays in a dedicated darkened room. Among the most famous works of Aboriginal video art to date, PolesApart transforms the enduring pain of the Stolen Generations into a resonant act of reclamation and embodied critique. The work directly quotes, and refutes, the romanticised narratives of colonial art, specifically targeting the landscapes of the Heidelberg School, such as Frederick McCubbin’s frontier triptych The Pioneer (1904), which systematically painted the Aboriginal body out of existence. The protagonist, played by the artist, their close-cropped hair hinting at a former cruel punishment, is depicted fleeing through the desolate, sepia-toned remains of a fire-scarred eucalypt forest. Signifying both mourning and the forced servitude imposed on removed children, the heavy, full-length 19th century dress is a constant burden, causing its wearer to falter and stumble amidst the bleak landscape of blackened silhouettes.

The PolesApart protagonist’s arduous journey re-animates the tragic history of the Stolen Generations, particularly referencing r e a’s grandmother and greataunt, who were forcibly removed from their families and sent to Cootamundra Girls’ Home. The figure’s desperate flight through the desolate, shadowed terrain,, embodies the deep trauma and enduring grief experienced by those wrenched from kin and Country. There is a quiet power in the fugitive’s unflagging, undeniable presence in a space designed to erase them, and even in their stoic reaction to the video’s final paint-splashing scenes, which reference both the Union Jack and the macho abstract art of Jackson Pollack. Their onscreen struggle transforms the historical facts of removal, often denied or minimised, into a dramatic image, repositioning the familiar painterly landscape as a site of knowing, active Aboriginal memory and resistance. “My art is the practice of reclamation; a disruption of the colonial gaze through re-storying the blak-body as a point of protest.” - r e a

In the wake of the 2023 Voice referendum, r e a has taken an iconic queer poster as inspiration to parallel the underlying politics that align queer and blak bodies. The AIDS activist slogan “SILENCE = DEATH,” which emerged during the 1980s, galvanized the queer community to publicly protest homophobic government inaction and neglect regarding the AIDS epidemic; it asserted that invisibility and voicelessness were lethal. By deploying this alongside the Aboriginal land rights slogan “LAND = RIGHTS,” r e a draws a powerful parallel between the distinct yet intertwined struggles for land rights and a political voice. Both slogans speak to the fatal consequences of state and societal erasure: just as land theft and denial of sovereignty result in the death of people, culture, and Country, so too does political marginalisation and enforced silence continue to threaten the lives of queer individuals. For a queer Blak artist, layering these messages connects the political struggle for an Aboriginal Voice in Australian politics to broader, ongoing struggles for literal existence and visibility.

r e a’s large banners depict the words for “sun” in the Gamilaraay, Wailwan and Biripi languages of the artist’s parents and grandparents, interjected by SILENCE = DEATH and LAND = RIGHTS, layering multiple messages for audiences to explore and decipher. With this work, r e a has positioned blak, queer power as unavoidable and immutable as the rise and fall of the sun, the light at the end of tunnel.

r e a, GARI (language), Rewriting Landscapes installation view, 2025, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental. Photography by Sam Roberts.

Aboriginal Refiguring ‘the figure in the landscape’

Darren Siwes, Libby Harward, Adam-Troy Francis and Colleen Strangways

Three of ACE’s large gallery walls are dedicated to photomedia artworks defined by the outstretched cross pose of their subjects: Darren Siwes’ Marrkidj wurd-ko (Cross Pose) (2011); Libby Harward’s Waribul Wayira (2020) and Adam-Troy Francis and Colleen Strangways’ Kungari (2025). In Darren Siwes’ photograph, it is the middle of three standing women who holds this pose, and the camera’s gaze; in Libby Harward’s video, it is the artist herself, seen in the aerial perspective of a drone shot; and in Francis and Strangways’ collaboration, dancer Francis, dressed as the black swan Kungari, crouches in the water with his wings stretched out wide.

Darren Siwes is an Australian artist of Ngalkban and Dutch descent, whose work explores the complex intersections of European and First Nations cultures. Working extensively with analogue photography in the early part of his career, Siwes created staged images that explore the possibilities of Aboriginal photography, using photomedia as a medium to challenge colonial narratives by asserting a First Nations way of seeing. His meticulously planned and composed photographs often feature figures in highly atmospheric or recognisable landscapes, using long-exposure, props and staging techniques to explore the interplay between place, memory presence and absence - hinting at both historical erasures of Blak bodies, and their re-assertion as active protagonists.

In Marrkidj wurd-ko, from the highly regarded series Dalabon Dalok, Siwes photographed his female relatives in their traditional homeland, Dalabon Country, in Central Arnhem Land. The work directly references one of the world’s most famous artworks - so-called “Old Master” Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing, Vitruvian Man, which depicts the allegedly ideal human form circumscribed by a square and a circle. Da Vinci’s drawing, itself a study of the Roman architect Vitruvius’ theories on proportion, has become a quintessential symbol of the Renaissance, humanism, and a specific, European ideal of human physical perfection. The figure, contained perfectly within the geometric harmony of the circle and the square, embodies a worldview that sought to order, measure, quantify and ultimately control and profit from the natural world. It is a symbol deeply embedded in the logic of the Enlightenment, and the colonial project that followed. Siwes subverts this culturally loaded Western ideal by replacing the old white man of da Vinci’s drawing with Aboriginal women gazing frankly back at the camera , recasting the exemplar of the “ideal human” as a proud Blak woman standing on her Country. Here, where the human body is not the measure of the world, but is instead measured by, and belongs to, Country. Like Troy-Anthony Baylis, Siwes’ artwork operates on multiple levels. His landscape photographs in the Dalabon Dalok series function both as gorgeous landscape photography and as a critique, in which the artist invites us to imagine a revised art history, one in which dismantles and rewrites the convention of the figure in the landscape from an Aboriginal perspective.

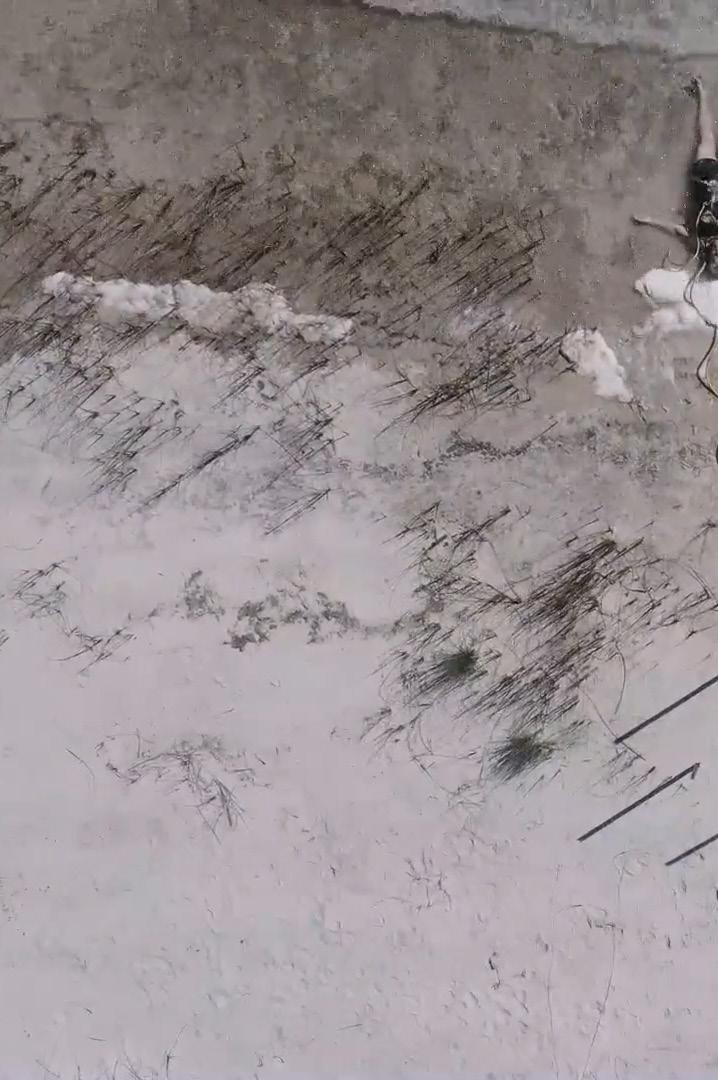

Libby Harward’s work Waribul Wayira (hungry waterways), situated adjacent to Siwes’ Marrikidj wurd-ko, also features a female figure in the landscape, but here, the figure, the artist herself, is shown laying on her back in the shallow water of a coastal shoreline. Across nearly two decades of creative practice, Harward, a Ngugi woman of the Quandamooka people, living in Jinibara Country/Sunshine Coast hinterland, south East Queensland, has explored relational projects (including the radical Aboriginal conversation space, Blak Laundry, at Tarnanthi Festival 2025), performance, installation, video, photography, and sound as tools to disrupt and break through the colonial layers that have been imposed on Country. Through a process she has described as listening, calling out and understanding, her considered, often conceptual artwork practice explores relationships between place, environment, language, gesture and ancestral memory.

Waribul Wayira (hungry waterways) is part of Harward’s ongoing exploration of the political and cultural significance of water in the project Deadstream. The work is a direct response to the colonial mismanagement of Australia’s ancient river systems, which has seen them over-extracted, commodified, and disrespected. In 2019, Harward undertook a 16000km round roadtrip down the Baaka river with her two children, listening to troubled waterways and creating a body of work which includes interview and documentary footage with filmed performance art actions. Here, Harward performs with a lawn sprinkler on the shoreline of a freshwater lakein the intertidal zone of her ancestral country of Mulgumpin-Moreton Island in the Quandamooka-Moreton Bay. Her use of the drone footage provides a view which, in its recalling of the aerial perspective of some Aboriginal art, offers a strong example of a sovereign First Nations gaze on the landscape. The slowturning sprinkler, as the great enabler of manicured lawns, is for Harward a symbol of gross European ineptitude toward the land and its needs, which has led to water systems becoming imbalanced, and going hungry.

Kungari is a photographic artwork uniting the practices of Adam-Troy Francis, a celebrated dancer, DJ and performer and Colleen Strangways, an award-winning photographer and filmmaker committed to cultural storytelling. Together, they created a soulful portrait on Ngarrindjeri Country at Raukkan, the cultural and spiritual heartland of the Ngarrindjeri Nation. Raukkan, meaning “meeting place,” is of immense historical significance. By choosing this sacred site, the artists root their contemporary image, produced entirely in-camera with no digital or AI effects, firmly within deep ancestral and political histories.

Kungari is the Ngarrindjeri name for the Black Swan (Cygnus atratus), which is a vital totem for certain Ngarrindjeri clans. For the Ngarrindjeri, the swan is inextricably linked to the health of the Lower Lakes and Coorong waterways, where families historically collected swan eggs as a major cultural activity. This practice embodies the traditional responsibilities of land and resource management, ensuring the survival of their totem. The image of Kungari, the Black Swan serves as a symbol of the connection between culture, heritage, identity, and ecosystems. In a context where the Murray-Darling river system is severely threatened, this image is more than portraiture; it is an urgent statement on environmental and cultural survival.

Kungari – Wings Over Kurangk

by Adam-Troy Francis

Before the light breaks, Kurangk (Coorong) lies in stillness waters like glass, holding the breath of Ruwe (Country). Mist curls low, and gliding through it comes KUNGARI black as the deep night, crowned with a beak like yarluwar (fire).

To the Ngarrindjeri, Kungari is more than bird. Kungari is Ngartji. Totem, law, kin.

Every beat of Kungari wings carries Ngurunderi’s journey, Every wingbeat echoes the paddles of Ngurunderi’s canoe, cutting through the dreaming rivers, shaping the Kurangk( Coorong), as Ponde (Murray Cod) swayed, forming stream and view. Bold wings brush sky, silhouette of ancestral law and care Ruwe (Country) weaving spirit into the flow of tides.

When kungari glides low over the reeds, the Ngarrindjeri Nukkan (watch). Kungari’s presence means ngoppun ruwe (our Country) is breathing wellKurangk (Coorong) waters are strong, ponde (Murray Cod Fish) are running, seasons are true.

Kungari is the promise kept between Ngarrindjeri and Ruwe (people & country). Kungari teaches patience: waiting with the tides. Kungari teaches courage: facing the storms.

Kungari teaches loyalty: returning always to the waters that raised Ngarrindjeri culture up.

And the Ngarrindjeri ngoppun (our walk towards) within the shadows on the water, for they yanun (talk/speak): Ngaitji-ngatta, ngaitji-ruwe (protect the spirit ancestors totem, protect the land and waters).

As long as Kungari call drifts across the Kurangk (Coorong) wind, the lore will be kept. Everything and everyone has a role to play. Ngarrindjeri will remain Nragi (deadly) Deep rooted like the reed rushes of Ngarrindjeri ruwe, soaring in Mi:wi (our intuition/spirit/heart) like kungari, the black swan of forever.

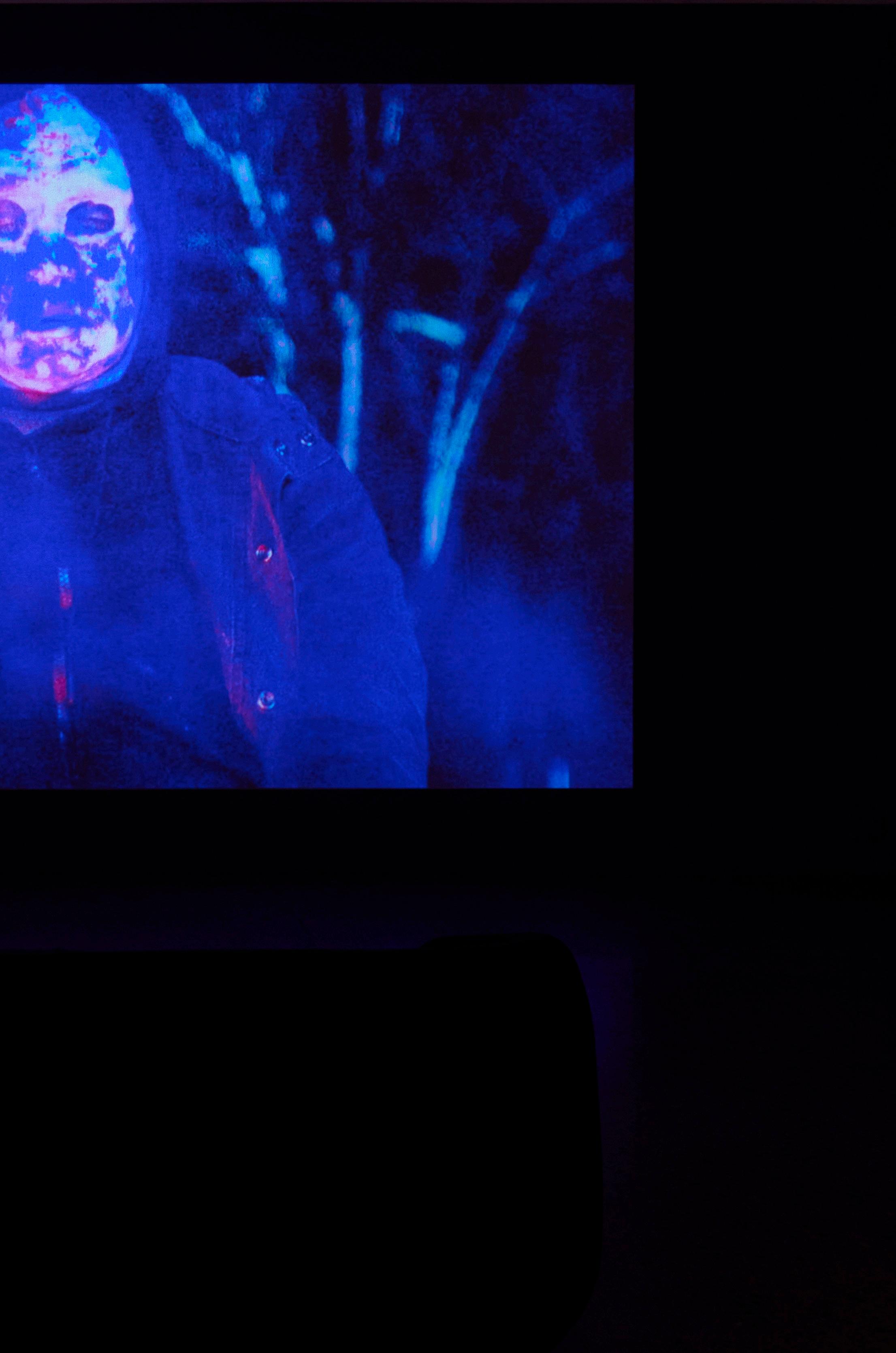

Patrick William Carter’s Balay Demons

Commissioned by Adelaide Contemporary Experimental

At the far end of the ACE gallery throughout Rewriting Landscapes, Patrick William Carter’s video work Balay Demons plays in a dedicated darkened screening space. Carter is a Noongar artist whose art is centred around his family and his experiences of life. Carter’s multi-disciplinary practice includes elements of painting, dance, performance and musical composition featuring his distinctive wavering vocals. He has developed a significant body of digital artworks, short films and large-scale projects exploring the challenges he faces in life, his love of family and Country, and the relationships between colour, movement and emotion. In the language of contemporary art, Carter’s work is interdisciplinary or hybrid, but the artist himself doesn’t observe traditional boundaries between media, preferring instead to weave meaning through his artworks, often guided by song and voice as starting points. ACE was fortunate to host Patrick William Carter for an intensive residency in May 2025, during which time Patrick painted, sang, met mob - and shared his love of horror movies with the ACE team.

The seeds of this work began during Patrick Carter’s painting trips on Noongar boodja (Noongar Country) with Kelton Pell, Sophia Thorne and Sam Fox. On these trips, Pat made work about his love and connection to Country, but he also sensed ancestors, spirits and scary feelings. And after painting all day in the bush, Pat started a practice of making home-made horror movies, like the ones he loves to watch, back at wherever the team were staying, and the team learned to “Balay” (or “Watch out!” in Noongar) for the demons’ attacks. These improvised, point-of-view experiments provided a skeleton for Pat to direct Balay Demons without a conventional script. Instead Pat used art direction and led improvisational play to communicate his vision to his collaborators and play out scenes of menace, terror and bewilderment in the landscape. In Balay Demons, Pat explores the complex feelings of being on Country, his own demons, and expresses his demand for agency through a fearsome alter-ego reigning in his beloved horror genre.

Sonic landscapes

Dylan Crismani is a contemporary composer of mixed Wiradjuri and European descent, known for instrument-building, and rigorous interrogation of experimental musical forms both materially and conceptually. A Glimmer of Hope originated from the artist’s contribution to the “Climate Notes” project, which asked composers to respond to personal letters penned by leading climate scientists. The overwhelming consensus from these letters was one of deep concern regarding the accelerating loss of planetary ecosystems. Yet, within this anxiety, the scientists consistently expressed a hope that humanity could still act decisively to avert the worst outcomes and learn to live in harmony with nature. Taking its title directly from a letter by Dr. Kevin E. Trenberth, Crismani’s work embodies, in sound, a critical duality: the recognition of a profound, unfolding global crisis, paired with an assertion of possibility.

Crismani’s composition for bell plates and violin explores this conceptual tension through innovative, experimental sonic techniques. The unpredictable timbres of the un-grooved bell plates, played with various mallets and brushes, create a variable, evocative aural landscape without visual cues, encouraging visitors to listen closely. This musical journey navigates themes of environmental fragility, using elements like the harmonically unstable 13:8 ratio (often associated with death in Western music) to convey the heavy subject matter, contrasting it with the delicate, fragile quality of violin natural harmonics, which metaphorically underscore the delicate balance of global ecosystems. A Glimmer of Hope functions as a sophisticated commentary on musical and artistic convention, while also asking us to expand our notion of what Aboriginal art can look - or in this case, sound, like. The work attempts a unique fusion of experimental music and classical form, structuring itself loosely around a conventional format while departing into ambitiously unconventional sonic territory not often associated with First Nations art practice. By utilising non-standard tunings and applying complex spectral techniques, learned in his PhD research and refined through his practice as a leading experimental composer, the artist has created a complex sound art work which stems from environmental crisis, but is grounded in hope. Crismani’s nuanced experimental practice challenges essentialist notions around contemporary First Nations art, highlighting the breadth and fluidity of contemporary Aboriginal art practice.

Bantay-Salakay installation view, 2025, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental.

Artists overwriting landscapes

This exhibition explores the wider project of many First Nations artists who are actively rewriting ideas about landscape and art in so doing, reframing art history. The colonial gaze historically framed the Australian continent as terra nullius; an empty land waiting to be inscribed with meaning by settlers. Landscape painting became a tool of possession, depicting a tamed, pastoral, or picturesquely savage wilderness devoid of its sovereign peoples. These artists disrupt this visual tradition. By placing assertive Aboriginal figures at the heart of their compositions, they re-inscribe the land with its true history and continuing cultural significance as sovereign Country.

Danni Zuvela Curator

Troy-Anthony Baylis

(Jawoyn people)

Troy-Anthony Baylis is an interdisciplinary artist whose practice across assemblage, painting, textiles, performance, and photography critically unsettles colonial imagery, reworking historical landscape paintings to expose and challenge the erasure of Aboriginal presence and the visual acts of possession embedded in Australia’s art history.

(left) Troy-Anthony Baylis, (pink) Pole 1 (2006); (pink) Pole 8 (2007); (pink) Pole 10 (2007), knitted acrylic yarn, Rewriting Landscapes installation view, 2025, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental. Photography by Sam Roberts.

(next page) Troy-Anthony Baylis, Making Camp at ‘Forest, Cunningham’s Gap, 1856’ (2009), from the series Making Camp 2009, pigmented inks on etching paper, Rewriting Landscapes installation view, 2025, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental. Photography by Sam Roberts.

r e a

(Gamilaraay/Wailwan/Biripi peoples)

r e a is an interdisciplinary artist, curator, and activist whose research-led practice reclaims cultural narratives and confronts historical erasure and intergenerational trauma through installation, painting, text, and new media.

(left) r e a, PolesApart (2009), single-channel video, colour, silent, 6 minutes, 22 seconds, Rewriting Landscapes installation view, 2025, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental. Photography by Sam Roberts.

(next page) r e a, GARI (language) (2024), vinyl banners, dimensions variable, Rewriting Landscapes installation view, 2025, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental. Photography by Sam Roberts.

Darren Siwes

(Ngalkbun people)

Darren Siwes is an Australian artist whose photographic practice interrogates the intersections of First Nations and European cultures, using staged and atmospheric imagery to challenge colonial narratives and reassert Blak presence within historical and contemporary landscapes.

Darren Siwes, Marrkidj wurd-ko (Cross Pose) (2011), from the series Dalabon Dalok (Dalabon Woman), giclée print on pearl paper, 120cm x 90cm, Rewriting Landscapes installation view, 2025, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental. Photography by Sam Roberts.

(Ngugi people)

Libby Harward is a Ngugi woman of the Quandamooka people whose multidisciplinary practice uses performance, installation, and conceptual processes of listening and calling out to disrupt colonial impositions on Country and explore the deep relationships between place, language, environment, and ancestral memory.

Libby Harward, Waribul Wayira (hungry waterways) (2020), single channel digital video, colour, sound, 2 minutes 43 seconds , Rewriting Landscapes installation view, 2025, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental. Photography by Sam Roberts.

Libby Harward

Adam-Troy Francisin collaboration with Colleen Strangways

(Kaurna, Ngarrindjeri, and Wirangu) (Arabana and Mudbura Walpiri)

Production team: Sarah Tickle, Lily Jing Wen and Benjamin Rees

Commissioned by Adelaide Contemporary Experimental

The collaboration of dancer and DJ Adam-Troy Francis and photographerfilmmaker Colleen Strangways brings together movement, identity, and cultural storytelling in a contemporary portrait of queer Blak expression in the ancestral and political significance of Raukkan, the spiritual heartland of the Ngarrindjeri Nation.

Adam-Troy Francis in collaboration with Colleen Strangways, Kungari (2025), digital photograph, Rewriting Landscapes installation view, 2025, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental. Photography by Sam Roberts.

Patrick William Carter

(Noongar people)

Patrick William Carter is a Noongar artist whose multidisciplinary practice, spanning painting, performance, film, and music, weaves together themes of family, Country, and emotion, using colour, movement, and his distinctive voice to create deeply personal and fluid expressions of lived experience.

Patrick William Carter, Balay Demons (2025), digital video, colour, sound, 19 minutes 23 seconds; rubber masks, acrylic paint, Rewriting Landscapes installation view, 2025, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental. Photography by Sam Roberts.

Dylan Crismani

(Wiradjuri)

Dylan Crismani is an experimental composer whose research-driven practice redefines sound through complex tuning systems and spectral techniques, expanding the boundaries of contemporary First Nations art with deeply reflective and innovative sonic works.

Dylan Crismani, A Glimmer of Hope (2024), experimental sound work for bell plates and violin, 9 minutes 19 seconds, Rewriting Landscapes installation view, 2025, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental. Photography by Sam Roberts.

List of Works

Troy-Anthony Baylis (Jawoyn people), Making Camp at ‘Forest, Cunningham’s Gap, 1856’ (2009), from the series Making Camp 2009, pigmented inks on etching paper, 29.5cm x 42cm.

Troy-Anthony Baylis (Jawoyn people), (pink) Pole 1 (2006); (pink) Pole 8 (2007); (pink) Pole 10 (2007), knitted acrylic yarn, dimensions variable.

r e a (Gamilaraay/Wailwan/Biripi peoples), PolesApart (2009), single-channel video, colour, silent, 6 minutes, 22 seconds.

r e a (Gamilaraay/Wailwan/Biripi peoples), GARI (language) (2024), vinyl banners, dimensions variable.

Darren Siwes (Ngalkbun people), Marrkidj wurd-ko (Cross Pose) (2011), from the series Dalabon Dalok (Dalabon Woman), giclée print on pearl paper, 120cm x 90cm.

Libby Harward (Ngugi people), Waribul Wayira (hungry waterways) (2020), single channel digital video, colour, sound, 2 minutes 43 seconds.

Adam-Troy Francis (Kaurna, Ngarrindjeri, and Wirangu) in collaboration with Colleen Strangways (Arabana and Mudbura Walpiri), Kungari (2025), digital photograph, dimensions variable.

Patrick William Carter (Noongar people), Balay Demons (2025), digital video, colour, sound, 19 minutes 23 seconds; rubber masks, acrylic paint, dimensions variable.

Dylan Crismani (Wiradjuri), A Glimmer of Hope (2024), experimental sound work for bell plates and violin, 9 minutes 19 seconds.

Support

Rewriting Landscapes is presented and supported by Tarnanthi: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art. Adam-Troy Francis is supported by City of Adelaide. Patrick William Carter is supported by the Western Australian Government through the Department of Creative Industries, Tourism and Sport (CITS).