Rumblings Within: Mark Valenzuela’s Bantay-Salakay

An ideas-driven exhibition

Mark Valenzuela’s exhibition Bantay-Salakay is the fifth iteration of the Porter Street Commission, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental’s annual new work commission for ambitious artistic thinking by South Australian artists.

While Valenzuela is widely recognised as South Australia’s most daring, experimental ceramicist, his wide-ranging artistic practice cannot be reduced to material interrogation. Rather, Valenzuela’s true material, as the accumulation of individual artworks in concrete, cotton, polyester and clay comprising Bantay-Salakay reveals, is ideas.

Bantay-Salakay is an ideas-driven exhibition framed by two particular concepts of significance to Valenzuela. These two ideas animate and connect the many individual and collective components the artist has brought together for this career-highlight showcase.

Bantay-Salakay performance traces, Performance: 1 August 2025, Adelaide Contemporary Experimental. Photography

1. Bantay-Salakay: Guard-attack

The first idea is the titular Bantay-Salakay, a Filipino sawikain (a proverbial saying) literally translating to “guard-attack”, a term used to describe a profound and insidious form of betrayal. It refers to a person, an institution or a system entrusted with protection that becomes the source of harm. It is not just a simple or expected enemy: bantay-salakay is the guardian who exploits, the caretaker who pillages, the politician undermining their own people. The protector who becomes a destroyer. The policeman who turns around and attacks. The foundation that should support – but instead, crumbles.

We can think of bantay-salakay as the “wolf in sheep’s clothing,” but with a deeper, systemic resonance. The term is not just about disguise, but about the subversion of a formal, trusted role with guardianship over the vulnerable. (In English some similar contradictory terms might be ‘the fox guarding the henhouse’, or ‘Dracula in charge of the blood bank’).

In an Australian context, and in Valenzuela’s birthplace of the Phillippines, it might echo the public’s mistrust in institutions that promise to serve but instead fail; the unease felt when the promise of security rings hollow; or the dark humour which everyday people use to cope with endemic corruption, cronyism and disappointment in political leaders meant to represent and care about, or at least, care for, us.

Mark Valenzuela gives us a specific name for that dark feeling of realising that the protector is secretly a predator: Bantay-Salakay.

We can sense this darkly ironic comment on power throughout the exhibition, from the tiny, vicious beasts, tethered by cockfighting ropes to gallows holding cast ceramic tyres, to the rumbling speakers housed inside fragile ceramic surrounds to the 4 tonnes of concrete rubble “reinforced” by mock-rebar made of delicate clay. We encourage you to read Dr Belinda Howden’s essay in this catalogue that expands in depth on the individual works making up this exhibition, including description and analysis of each, together with direct quotes from the artist himself.

2. Pakikipagkapwa: The act of bridging the distance between human beings

Building on the foundation of wordplay established with the concept bantaysalakay, Valenzuela’s conception of his Porter Street Commission has been deeply informed by a second framing idea that is almost its complete opposite: pakikipagkapwa.

If Bantay-Salakay offers a stark view of our world as an unsafe place of compromised structures and betrayed trust, then the exhibition’s second guiding idea, pakikipagkapwa, generates a duality that is necessary, even beautiful. Thinking about Bantay-Salakay in relation to pakikipagkapwa moves the conversation from a diagnosis of failure, to a proposal for, if not exactly healing then a potential antidote, or repair.

This counterpoint, and perhaps the very heart of Mark Valenzuela’s practice, is the Filipino concept of pakikipagkapwa. Pakikipagkapwa, a commonplace term in the Philippines, is a term almost untranslatable into Australian English, because it refers to a sense of common humanity that is itself increasingly alien to commodity-driven, acquisitive, individualistic societies such as ours.

To translate pakikipagkapwa as simply “collaboration” or “community” would be to miss its exceptional depth and specific profundity. The term is rooted in the word kapwa, which means “fellow human being,” but more accurately describes a “shared inner self.” Kapwa is the recognition of oneself in another; of our inextricable, inalienable togetherness.

Pakikipagkapwa is the active, ongoing process of connecting with others on the basis of this shared identity, this shared one-ness. It is a conscious act of bridging the distance between people, of seeing another person – any other person – not as “other,” but as part of oneself (and, accordingly, oneself as part of another). It is responsibility for others as a condition of one’s selfhood. It is the ethical and emotional labour required not just to generate but to also acknowledge, at the base level, true kinship and solidarity. The recognition that mutual aid is as much a condition of humanity as mutual struggle.

Where bantay-salakay exposes the failure of reinforcement from within, pakikipagkapwa demonstrates how to build genuine strength from within. This is not a theoretical idea in the exhibition; it is its core methodology. The artist, known for a practice deeply invested in long-term cultural exchange and community building, has woven a network of trust directly into the show’s fabric.

We see this vividly in the front gallery space, which was activated at Input/Output on 19th of July by a central collaboration with South Australian artists and long-term comrades of Valenzuela’s Alycia Bennett and Miles Dunne. Their collaborative performance, a carefully orchestrated interplay of sound, light, and live action centred around the kariton/sari-sari/paipitan structure and punctuated with strobes and intense games of chess between Valenzuela and members of the general public, was a living embodiment of pakikipagkapwa

(Further communal, community activities will be held throughout the exhibition). Chess itself is a dialogue; it demands intense focus on the other player, an understanding of a shared system, and a relationship built on mutual respect, responsiveness, and strategy. The performance created a temporary community, a space held together not by concrete and iron, but by shared experience, attention, the intertwining vibrationary spectra of light and sound, and the trust inherent in live art and performance.

We see it also in the screenprinted flour sacks that hang like a banner on the main gallery’s northern wall. Skewering the pomposity of the colonising Spanish conquistadors, Valenzuela reduces them to a caricature, a decorative motif which serves instead to re-emphasise their repurposed supports, the flour sacks that are the stuff of Filipino everyday life, holding the flour that is used to make pandesal, a kind of sweet baked bread that is made and eaten every day. The generals are nothing but a thin layer on the act that really matters, the act that joins Filipino families across the nation and across the world: the making and sharing of the daily bread.

This principle of pakikipagkapwa extends to the very objects of protection within the exhibition themselves. These objects counterpoint and, to some extent, neutralise, the exhibition’s other objects of offence and power.

In the front room, hanging from the kariton (food cart)/ sari-sari (mixed goods stall) structure is a suite of anting-anting (smaller, individual amulets), each crafted by fellow talented maker and long-term mentee of Valenzuela’s, Mikoo Cataylo. Each one is a small testament to the protective power generated not from brute force or untrammelled power, but from creative trust, belief and shared cultural heritage. Here, the exhibition presents a powerful material counter-narrative to the compromised ceramic rebar. While the rebar performs a lie (the illusion of structural support – a physical critique of the twisted, tired system of colonial capitalism) these anting-anting offer a different kind of reinforcement. Forged through friendship, mutual inspiration and creative exchange, they represent spiritual, cultural and communal protection. Their power comes from the trust, care and communication invested in their creation, a tangible outcome of pakikipagkapwa.

In the grey room sits the large agimat structure. Taking the form of a vest, it references a specific kind of Filipino amulet worn on the body as a source of spiritual power and invulnerability. Unlike the cold, impersonal, industrial promise of concrete, the agimat offers protection that is embodied, a second skin of belief worn close to the heart. This is a shield for a human being.

Traditionally, the power of an agimat is unlocked through ritual, prayer, and, importantly, chanting, which harnesses resonance of sound. The exhibition draws a direct line from this tradition to the collaborative sound performance activating its space, prior to the official opening, on opening night, and at subsequent events, proposing that sound itself is a radical agent of pakikipagkapwa.

Sound, more than any other medium, physically enacts the process of connection. As pure vibration, it travels through the shared air to touch everyone in a room, dissolving the illusion of separation between bodies and connecting all in a single, resonant field in time. It is a force that is felt in the chest as much as it is heard by the ears. In the rhythm of the performance, sound becomes the invisible architecture of community, a current that can synchronise heartbeats and breath, fostering a pre-verbal sense of oneness. It is a potent reminder that the deepest forms of protection and connection are not built or intellectualised but felt, generated in the space between us, vibrating through organs and bone.

This exhibition places these two powerful Filipino concepts in dialogue. It dances between these ideas, often simultaneously and contradictorily, threat and care co-existing warily, creating new terrains for new conditions of thought across its complex suite of components.

It presents us with the rubble of bantay-salakay, a world where defense becomes offence and guardians become predators. But amidst the ruins, it resolutely models a path forward through pakikipagkapwa.

It suggests that if the formal structures our predecessors have built are untrustworthy, fragile or doomed to fail us, if colonial capitalism’s broken spine is showing, then our most durable, resilient, and genuine source of strength can be found in the connections we forge across alienation, with each other, in the act of closely connecting. In this exhibition, Mark Valenzuela, master chess player, is offering not just a critique, or even a warning; it is an invitation to rebuild, not with concrete and steel, but with trust, with care, and with acts of defiant recognition of our shared self.

Danni Zuvela Curator

by Lana

by Morgan Sette.

Bantay-Salakay

In 2003, at a contemporary art gallery in central Beijing, four pairs of trained fighting dogs were made to face off. The American Pit Bull Terriers were leashed up and individually siloed in metal cages mounted onto motorised treadmills, facing one another. The dogs were sicced into action, perpetually running towards each other without ever making contact. The scene was all muscle and jaws and futility.

Dogs who cannot touch each other, by Chinese artist-couple Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, was largely uncontroversial when first viewed as a live installation at Todays Art Museum in China. It wasn’t until 2017, when video documentation of the event was exhibited at The Guggenheim, New York, as part of a survey of Chinese art post-1989, that the work drew public criticism. The Guggenheim became the focus of boycotts and animal rights protests (no animals were actually harmed in the making of the work), and while the curators chose to keep the video on display, the museum was compelled to issue a defending statement. On the controversy, Yuan plainly responded, ‘…human nature and animal nature are the same.’ 1

1 Sun Yuan in conversation with Paul Gladston, Deconstructing Contemporary Chinese Art: Selected Critical Writings and Conversations, 2007-2014 (Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2016), 131.

It’s gauche to introduce an artist’s practice through the lens of another. But Dogs who cannot touch each other is useful for understanding Mark Valenzuela’s exhibition Bantay-Salakay, where even the title acts like two dogs facing off. In Tagalog, bantay means to guard or watch, while salakay is to attack. It is a contrary turn of phrase colloquially applied to politicians or police; those most entrusted to protect are those most likely to abuse such power. For Valenzuela, bantay salakay is also a personal antagonism. It is a metaphor for being an ‘occupant of both spaces’2 – that is, Australia and the Philippines. This makes bantay salakay a linguistic vector. It captures Valenzuela’s idiosyncratic artistic vision–which carefully observes Australia through the lens of the Philippines, and vice versa–and is a sweeping socio-political critique of dominion and control, a phenomenon found anywhere.

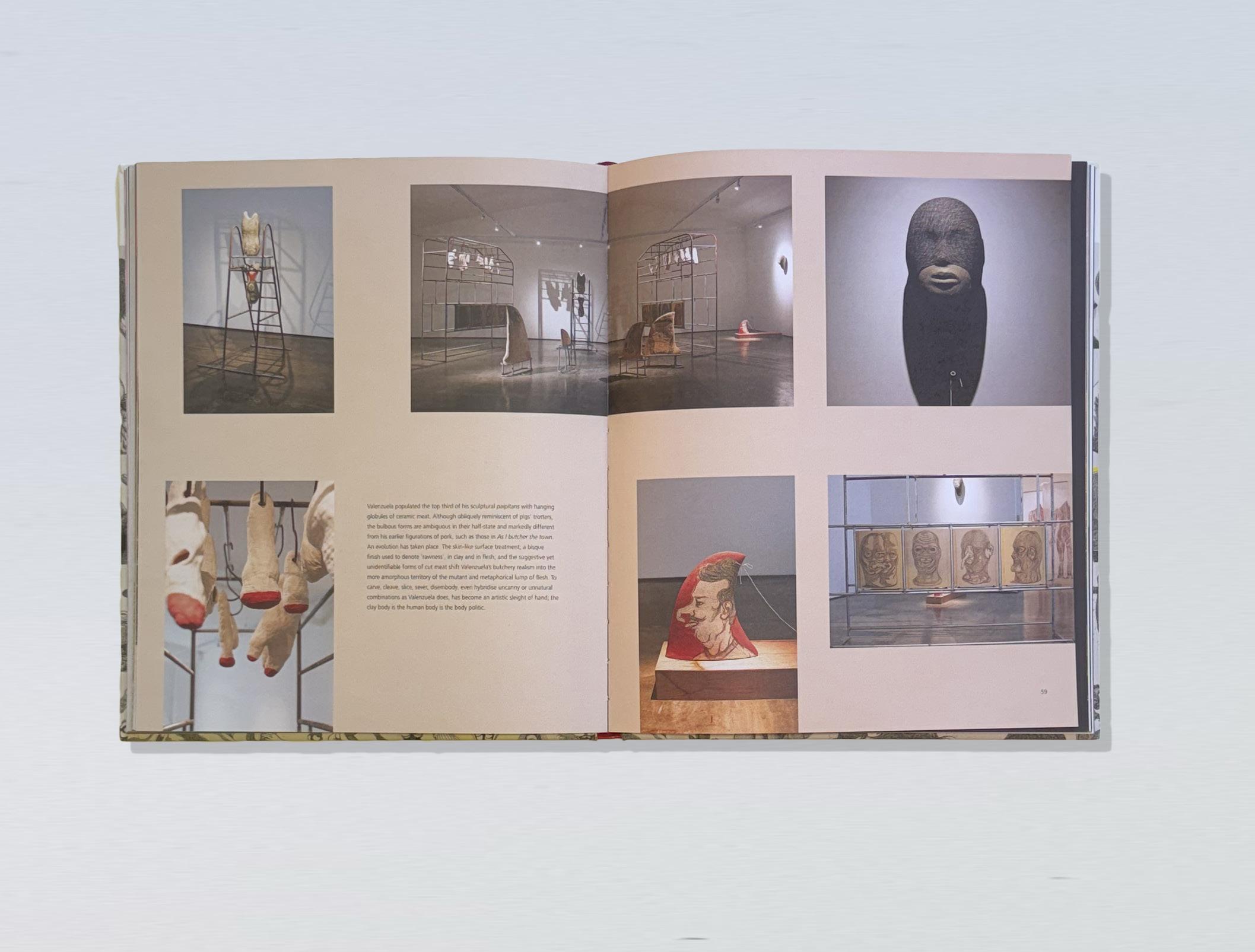

Bantay-Salakay features five new bodies of work, though that description feels reductive for an artist who views his practice as an ‘ongoing idea that never ends’. Valenzuela is right. No cluster of objects or individual ceramic works are titled and the exhibition itself is testament to his iterative mode of installationmaking. For example, in the eastern corner of the main gallery, five gallows-style wooden structures are decorated with ceramic tyres, their surfaces inscribed with ‘VULCANIZING’ (note, the Americanised spelling). The ceramic tyre is a recurring object, having literally been used before in earlier installations such as Once Bitten, Twice Shy (2020). Vulcanising is also a recurring concept. Bolkit–a Cebuano malapropism of Vulcan–is a catch-all term for roadside tyre repair services and, for Valenzuela, emblematic of the DIY ethos and resourcefulness of Filipino life. He carries the philosophy with him, repurposing objects, reusing forms, found objects and images, transforming their meaning as he goes.

The gallows also feature tethered ceramic forms modelled on three corner jacks, a declared weed in South Australia. These ceramic invaders are positioned equidistant from one another, two of which face off with the titular ‘bantay’ and ‘salakay’. Their colourful nylon ropes are the same used to tether cockfighting roosters to rudimentary perches and makeshift shelters, a phenomenon witnessed on the streets as well as farms dedicated to the sport across the Philippines. Valenzuela captured video of it on his last trip back. Groomed to fight, the roosters are kept close enough to incite territorialism but restricted from touching. The scene is all talons and crowing and futility.

2 Conversation with the author, Adelaide, 17 July 2025. Applies to subsequent quotes.

3 Ibid.

Three corner jacks make an appearance on the opposing textile installation too, this time donning a police hat. For Valenzuela, the weed is bantay salakay in action: ‘The thorns are a defence mechanism but that’s also how they attach and invade. It’s a form of survival. It’s the same in human beings.’ Along with an absurdly hirsute Spanish conquistador (another emblem of militarised control), the two images are silkscreened onto a large scale banner, propagating its surface and nearby gallery walls. Valenzuela made the banner out of repurposed General and Isla branded flour sacks – more resourcefulness, more transmogrification. The image of the conquistador also throws back to the tethered ceramics, one of which is brandished ‘conquestadores’ – a hybridised English-Spanish-Filipino spelling. More word play.

For Bantay-Salakay, Valenzuela has siphoned offer precious exhibition space to showcase a suite of artist collaborations, another ongoing idea that never ends. Valenzuela has always valued artistic and cross-cultural exchange and manufactured opportunities to bring Filipino artists to Australia, and vice versa. Formerly, this was through the curatorial project Boxplot, devised and coordinated alongside his partner Anna O’Loughlin, which naturally ceased during the covid years. Exchange is now revitalised as an informal artist residency in their home and backyard studio, here in Adelaide.

The front space of ACE houses these collaborations, including sound and light installations and performances by Adelaide-based artists Alycia Bennett and Miles Dunne. But the cornerstone object is a metal sculpture modelled on three common features of Filipino street life: kariton, a pushcart used to transport goods; sari-sari, a small neighbourhood convenience store; and paipitan, a metal cage used to individually silo and transport sows ready for slaughter. The sari-sari has made a prior appearance in Valenzuela’s practice. Tambay, from 2019, was a makeshift pop-up store “selling” ceramic pig heads, tyres and fish tails, made with his long-time collaborator Pablo Capati III. The paipitan has also made an earlier appearance. For Cheap Tricks (2018), Valenzuela powerfully repurposed real steel paipitan and decorated them with butchered ceramic pig trotters. Strikingly, the paipitan bears a strong resemblance to the cage that housed the pit bulls.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

At the bottom of Valenzuela’s hybrid metal form is a choreography of terracotta fish heads. Again, he has reached deep into his archive. Fish heads first appeared in Zugzwang (2011), as a shipping crate full of hostile piranhas. Nearly a decade and a half later, they are reimagined as street food delicacies, above which spins a 100-peso fan Valenzuela brought back on his last visit. With blades replaced by flailing plastic cellophane, the fan shoos away the (non-existent) flies. It is one of many common Filipino practices Valenzuela has observed anew, ‘…these things are a novelty since being in Australia. It’s almost like kinetic art.’

Literal background noise–of street vendors, cawing roosters, the tinny engines of tricycles–is novel again too and constitutes one of the newest elements of Valenzuela’s expanded practice: sound. In the far western end of the gallery, Valenzuela has recreated an agimat vest – a pre-colonial amulet believed to ward off bullets and other types of peril. Valenzuela’s large scale steel vest is populated with vibrating ceramic speakers, forms that are partially modelled on the three corner jack. Their flared, circular mouths are strategically perched on the frame–at the shoulders, heart, across the stomach–and sound off against one another. It is an ambi-sonic experience – bantay salakay from all directions.

While Spanish rule and the Catholic church widely suppressed pre-colonial animist beliefs, the agimat was revived during the 1896 Philippine Revolution by rebels and the peasant classes. It was worn as a protective measure. The nineteenth century version of these garments features hybridised ‘folk-catholic prayers in a Filipino peasant’s butchered Latin’, but they were ultimately pagan objects.6 Rituals like fasting, prayers and other animist practices were the only way to enact its blessings.7 Valenzuela’s sonic agimat echoes through to the front space where, on the paipitan/sari-sari/kariton sculpture, hangs a suite of anting-anting – another animist amulet. While much smaller in scale, these ceramic talismans are no less powerful and believed to be similarly protective. In this case, they are made by Filipino ceramicist Mikoo Cataylo, another long-time mentee and collaborator of Valenzuela’s. Cataylo has crafted his anting-anting while in residence with Valenzuela and his family in Adelaide over the last three months.

6 Geronimo Cristobal, ‘Bulletproof Equations’, blog, 29 October 2022

7 Ibid.

8 Conversation with the author, Adelaide, 27 July 2025.

Back in the main gallery, there is an installation of broken concrete slabs pierced with ceramic rebar. Made from high-fired paper clay, the rebar sticks out in twisted, spasmodic forms, fragile and unable to reinforce anything as originally intended. More futility. To be heavy handed about it, this is the most “Australian” visual moment in Bantay-Salakay. Ever the opportunist, Valenzuela spent three years scouring the streets and suburbs of Adelaide, gathering crumbling concrete ruins and scoring big when his own street–Victoria Street in Queenstown–was carved up with roadworks. Valenzuela jokes, ‘I might have the most colonial address in the country.8

Here, concrete seems to represent Australia – it’s bureaucracy, it’s overbearing rules and regulations. But the greyed out material, which almost disappears into ACE’s terrazzo flooring, is also a stand-in for the subtlety of Australia as a visual, sensory experience. In contrast to the kitsch garishness of cockfighting tethers or the cheap cellophane fan or Valenzuela’s maximalist artistic tendencies, more generally, the concrete installation is near-monochromatic and paired back in its bisque-only finish. As Valenzuela describes, ‘there you see quickly. Here, you have to observe deeply.’

It is unsurprising that Dogs who cannot touch each other triggered greater moral panic in the American context than its country of origin. Symbolically, the pit bulls challenge Western cultural attitudes towards animal life, which can be more highly valued than human life or, at least, offers a subjectivity more open to projection. The dogs also deftly transformed Chinese imperialism into American imperialism – a subject a Filipino artist might know something about. Valenzuela admits, viewing a culture through the lens of another is antagonistic. ‘Distance helps me to re-see things. Every time I go, I have to negotiate. I have to reintroduce myself. I go there and I am the person complaining. I come back and do the same. It is constant discontentment and comparison – it’s deadly.’9 In a game against himself, Valenzuela offends and defends, he attacks and he guards. This is bantay salakay.

8 Conversation, 17 July 2025, and subsequent quote.

9 Ibid.

Dr Belinda Howden Assistant Editor at Artlink Magazine

Each of Mark Valenzuela’s installations is a system of unlikely energies - a scheme of improbable pairs. Speakers sit snuggly inside bisque-fired clay trumpets; a demolished chunk of kerb is threaded with fragile cast-porcelain rebar; a metal market cart is strung up with terracotta fish heads; and used flour sacks bleed with silk-screen-printed images. Form, sound, motion and image conspire to create a third space full of heat, noise and weight. It all feels palpably dangerous, as if the speakers will self-destruct, the tonnes of excavated road will break and crush - the cable ties barely hold it together. Yet Bantay-Salakay is a robust sculptural proposition, pulsing with power and play.

When I first visited Mark’s studio in 2018, after I’d seen his exhibition at Adelaide Central School of Art, it was a revelation. I could visualize his process. A studio visit with Mark is like a gradually unfolding performance – there is the ritual of the first coffee, the welcome, the hospitality of Mark and his partner Anna O’Loughlin, their children coming and going. Mark and Anna import their coffee beans from the Philipines (their single origin coffee roastery is called Background Noise and they also run Boxplot Curatorial Projects together). The ceramic cups we drink from are made by Mark or one of his many artist friends from Asia or Australia. The walk to the studio involves a tour through the garden – designed, planted and grown by Mark and Anna. There’s always guerilla ceramics to be found, an errant tyre or duck hidden in the undergrowth. The studio was created in two halves – an open air, but covered space with kilns,

multiple pottery wheels, tables for hand-building, and racks holding his sculptures in various phases of drying, bisque-firing and glazing. A physical place of making. Then – the studio – an artist’s sanctuary from another era. A chess-game in play, a small kiln warming the space, a desk for drawing, an area for painting, a corner for assembling, a seat for reading. The entire space has been constructed by the artist with found windows, doors, purposeful shelves, the walls punctuated by precious objects gifted or found, junk reconstituted into art. Every surface is curated, every article in dynamic dialogue with every other. I’m reminded of Orhan Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence in Istanbul, or Kawaii Kanjiro’s home studio in Kyoto – its motto is ‘we do not work alone’. Mark’s place is a hermetic universe of sympathetic energies, all conspiring towards gentle focus.

In stark contrast, to behold Mark’s exhibition at ACE is necessarily overwhelming. The tension is palpaple – chaos this stunning can only be achieved through total control – and many hands. Mark is bridging a divide - the sheer effort in translating and transforming across two cultures is also the driving force in his installations and performances. There is excess generosity and extreme hard work, time and testing. A community of artists and friends made this with him. Yet, its mischievous exuberance gives the audience so much energy. You are revived. You are fed, nourished, recharged. From destruction comes a new cycle, a new era of experimentation.

Mark’s work is his energy distilled and unleashed. When he takes you through his home, his garden, his studio, and into his galleries, he is full of glee. The ambition and scale of his plans is always unbelievable – if you were an artist who toiled alone. But Mark’s approach to making and living is communal, inclusive – an act of radical hospitality – you are also a part of it before you know it. Don’t be scared.

Leigh Robb Curator of Contemporary Art at the Art Gallery of South Australia

Support

Mark Valenzuela is the 2025 recipient of the Porter Street Commission – ACE’s annual award supporting new artwork commissions by South Australian artists.

ACE is supported by the Australian Government through Creative Australia, its principal arts investment and advisory body and by the Government of South Australia through Create SA.

The performance program is supported by City of Adelaide.