One Hundred Aspects of the Moon

note to the reader

The impressions of the “One Hundred Aspects of the Moon” illustrated in this volume are from the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, with the exception of plates 17, 69, 91, and 92, which belong to the British Museum. The plates have been reproduced as closely as possible to their original oban size. Certain marks and discolorations not original to the prints have been touched out. In some cases, margins have been retouched or slightly enlarged for a more uniform appearance.

The dates on which the “One Hundred Aspects of the Moon” were printed and published are given in the format day.month.year; see page 70.

Numbers in the margins of the text refer to relevant plates of the “One Hundred Aspects of the Moon.”

Japanese place names and words that have entered the English language, such as Tokyo, Shinto, Noh, ukiyo-e, ronin, etc., are not given diacritical marks or italicized. No punctuation is given in the italicized Japanese text. Japanese personal names are given family name first, with the exception of Masami Teraoka.

Several systems are in use to date the various periods of Japanese history, and dates given here may differ from other sources.

Footnotes have been limited for the sake of readability, and interested readers are referred to the bibliography.

acknowledgments

The author extends his warmest thanks to Martha Avery, Paul Berry, Liza Dalby, John Fairman, Rebecca Johnson, Roger Keyes, Wah Lui, Ed Marquand, Haruo Matsuoka, Kyoko Selden, and Russell Steele for their expertise so generously shared. Especial thanks to Min Yee, great catalyst, who makes ideas reality.

One cannot study Yoshitoshi’s work without incurring a debt to the pioneering scholarship of Roger Keyes. The author wishes to express his gratitude to this inspiring figure, particularly for the biographical material assembled in his doctoral thesis, Courage and Silence: A Study of the Life and Color Woodblock Prints of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi.

front cover : Detail of plate 11, Shijō nōryō, “Cooling off at Shijō.”

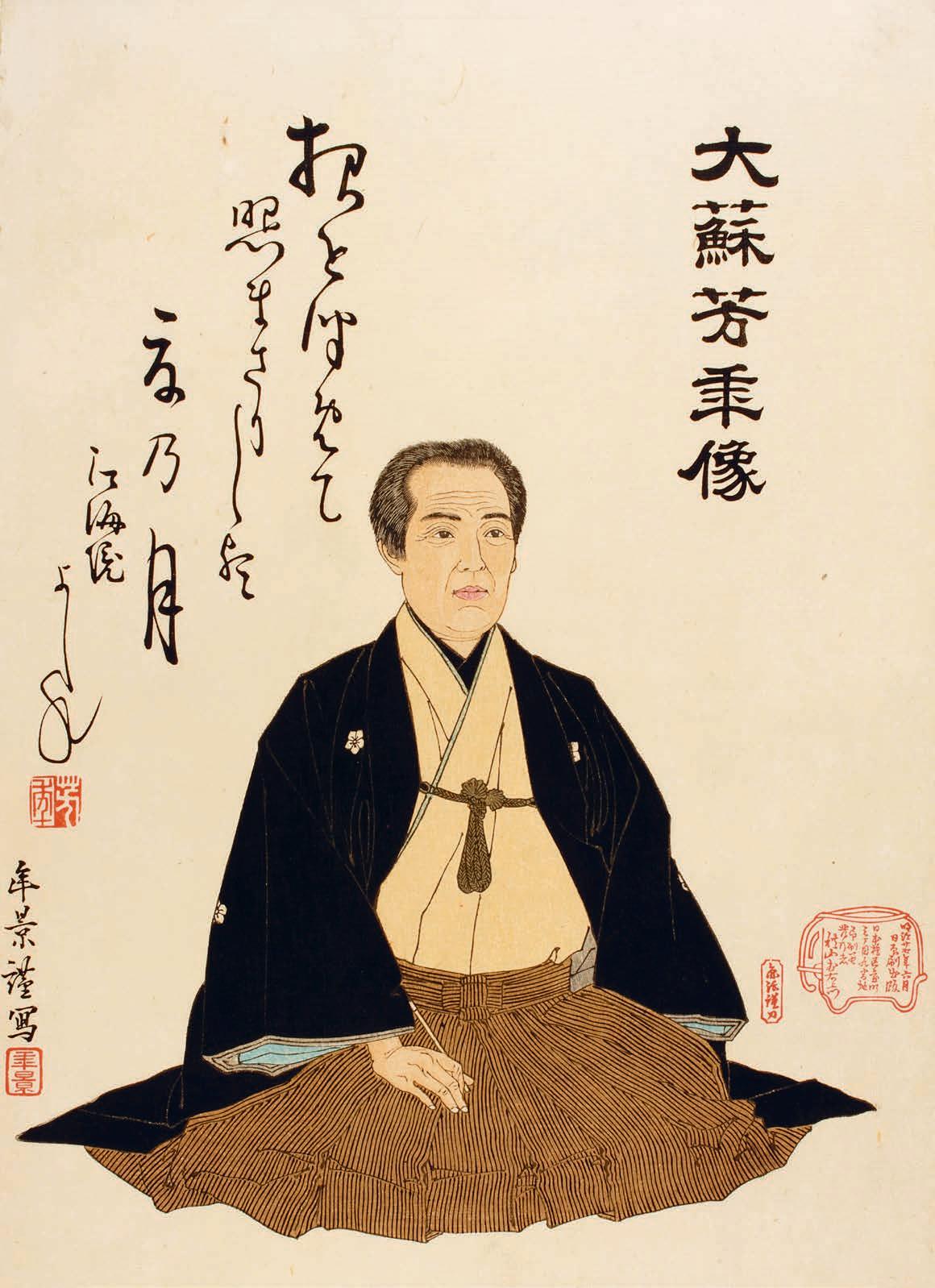

back cover : Memorial portrait of Yoshitoshi, 1892. See fig. 1.

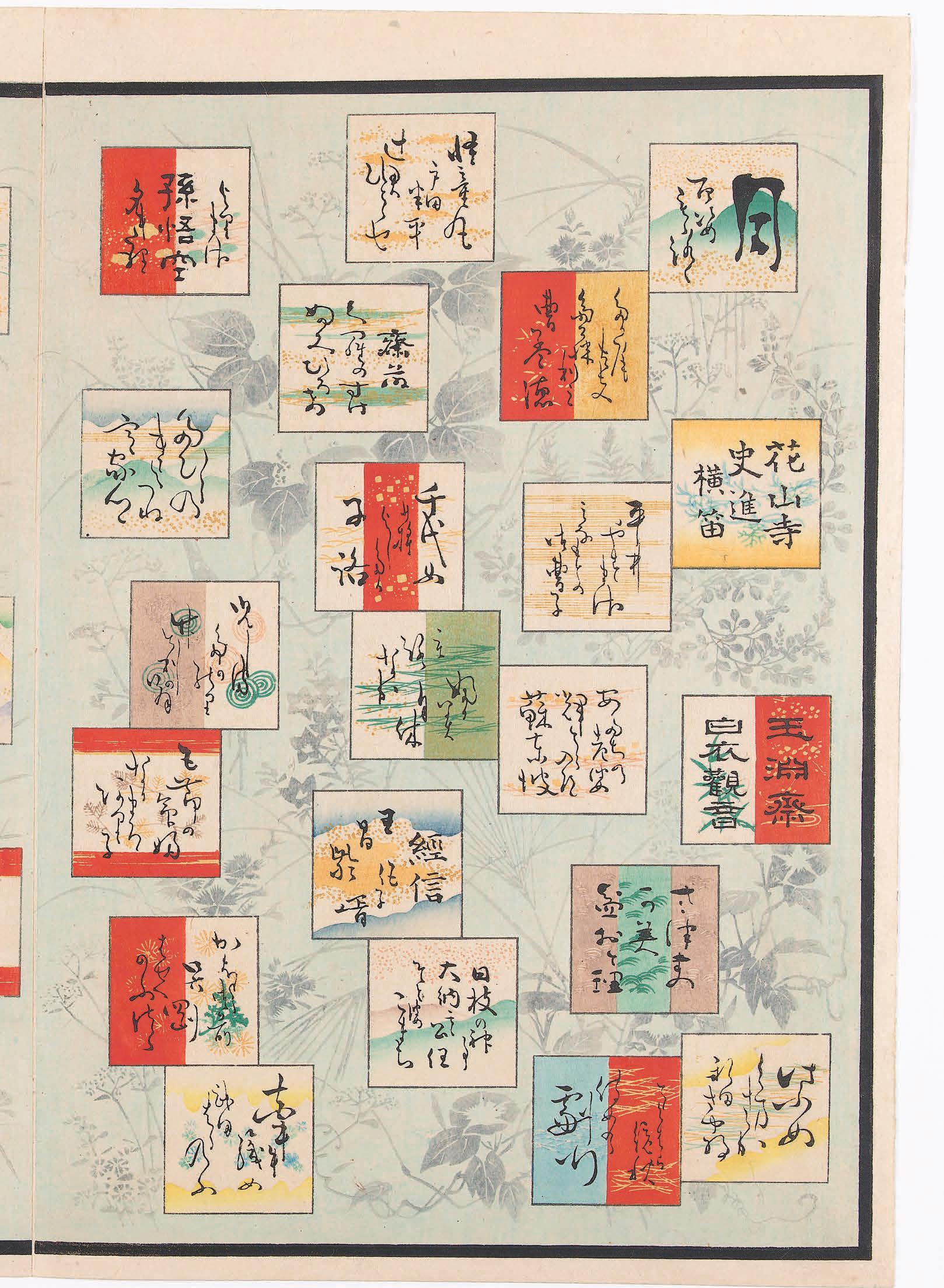

frontispiece : Title page of an album of “One Hundred Aspects of the Moon,” 1892. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

photography credits

© 2018 Philadelphia Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence: front and back cover, frontispiece, plates 1–16, 18–68, 70–90, 93–100; figs. 1, 14, 17, 23, 26–28, 30, 31, 33, 38, 50–62.

© British Museum, London, Dist. RMN–Grand Palais/Trustees of the British Museum: plates 17, 69, 91, 92.

© 2018 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston/Scala, Florence: figs. 2–4, 13, 15, 16, 40.

© Los Angeles County Museum of Art: figs. 5, 12, 18–21, 29, 32, 35, 41, 43–45, 47.

© Private collection: figs. 6–11, 22, 24, 25, 34, 37.

© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam: figs. 36, 39, 46, 63.

© Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: fig. 42

© State Library Victoria, Melbourne: figs. 48, 49.

A previous edition of this book, reproducing different impressions of the “One Hundred Aspects of the Moon,” was published in 1992 by the San Francisco Graphic Society and in 2001 by Hotei Publishing.

Copyright © 2018 Editio-Éditions Citadelles & Mazenod. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries should be addressed to Abbeville Press, 655 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017. The text of this book was set in Rilke. Printed in China.

for the cit adelles & mazenod edition

Editor: Geneviève Rudolf

Editorial assistant: Gwenaël Ben Aïssa

Photo research: Marion Jouan

for the abbeville press edition

Designer: Misha Beletsky

Production manager: Louise Kurtz

Production editor: Amanda Killian

First Abbeville Press edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 isbn 978-0-7892-1355-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request

For bulk and premium sales and for text adoption procedures, write to Customer Service Manager, Abbeville Press, 655 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, or call 1-800-Artbook

Visit Abbeville Press online at www.abbeville.com.

Contents

Holding Back the Night: A Biography of Yoshitoshi 7

One Hundred Aspects of the Moon: An Introduction 51

Technical Details 61

Map of Locations of the Stories 66

Timeline 68

Dating Meiji Prints 70

Notes on the Lunar Calendar 70

Akiyama Buemon’s Albums 71

Plates and Commentaries 77

Bibliography 278

Index 279

accept money from a Buddhist priest to get back to Edo. He returned to Kōfu not long after to recuperate from an eye disease that threatened to blind him.

In this lawless period, when every execution ground was full, Yoshitoshi’s sketchbooks included corpses and decapitated heads. These sketches formed the basis of battle prints, especially triptychs, that he designed in Kuniyoshi’s extravagant and bloody style. These prints were fairly well received, and in 1865 an Edo newspaper ranked him tenth in a list of ukiyo-e artists.

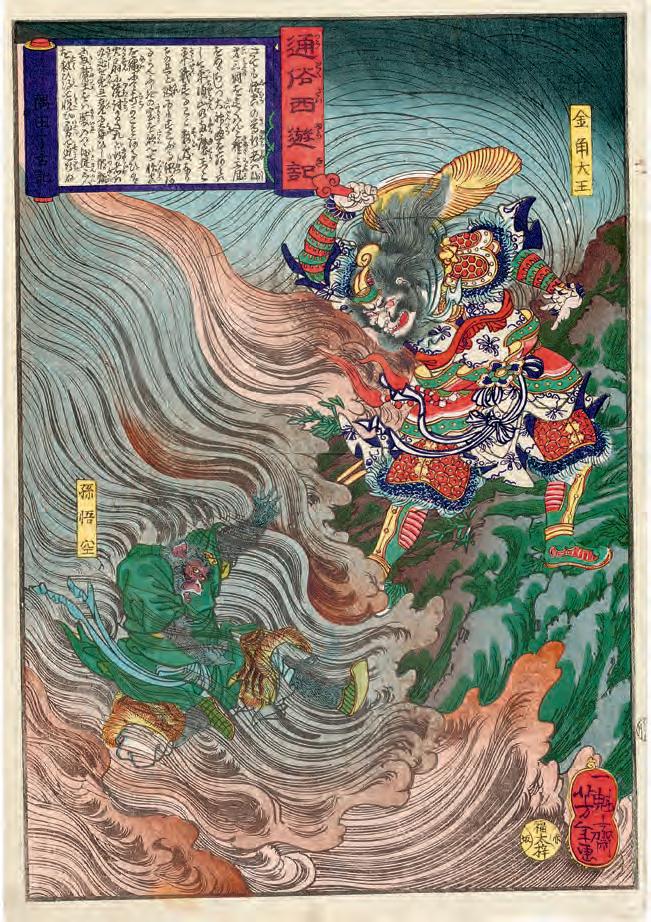

Most of Yoshitoshi’s designs during this period had rather derivative military or historical subjects, but in 1865 he also produced two more original and imaginative series. One was Tsūzoku saiyūki, “A Modern Journey to the West” (fig. 3), portraying the folk-character Monkey in episodes from a perennially popular Chinese story that had also entered the mainstream of Japanese folk culture. The other series was called Wakan hyaku monogatari, “One Hundred Tales of China and Japan” (fig. 4), after a game in which players took turns recounting a hundred short ghost stories, extinguishing a candle at the end of each story, till they were in darkness.

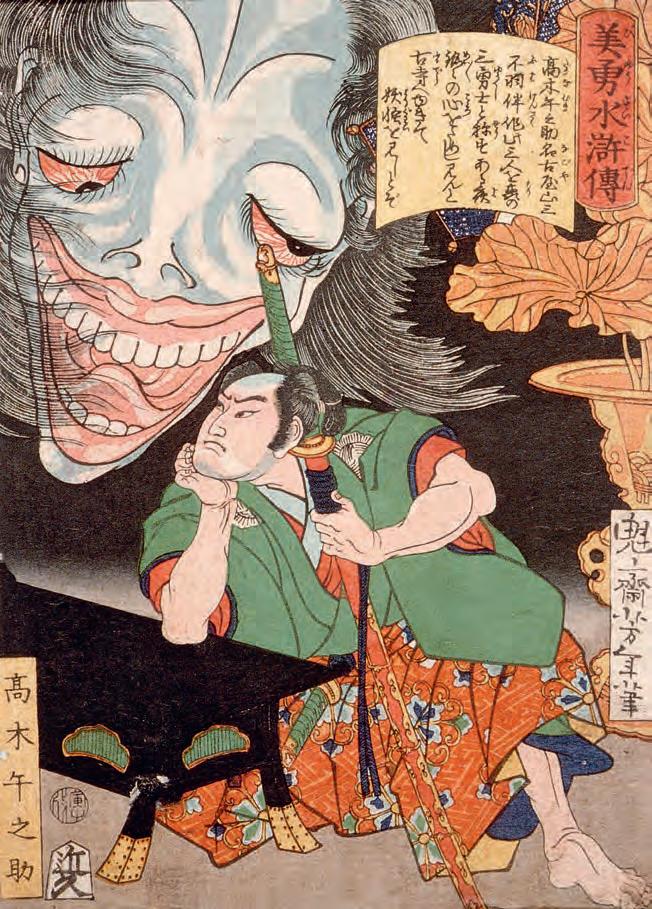

The following year, 1866, saw another imaginative venture, a half-size series of prints of the heroes of the Suikoden, “Water Margin,” a Chinese novel translated into Japanese at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Hokusai was the first Japanese print artist to illustrate the story, and Kuniyoshi’s own flamboyant version made his reputation in the late 1820s. Yoshitoshi again treats his material in a fanciful and original manner (fig. 5). He was already designing lively prints that were different from any others being produced at the time. That they were popular with the general public is indicated by the large number of impressions made from worn blocks that have survived.

Yet in the same year he designed the awkward and immature Kinsei kyōgiden, “Biographies of

3. Tsūzoku saiyūki, “A Modern Journey to the West,” 1865. Monkey struggles with Kinkaku Daiō. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

2. Tōkaidō, “ The Tōkaidō Highway,” 1863. Noh performance in Kyoto. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Modern Men.” The series illustrates personalities in a power struggle between two rival gambling rings in Chiba, the province east of Edo. The quarrel caught the public imagination and became the subject matter of novels, Kabuki plays, and woodblock prints. The series is a good example of ukiyo-e’s popular roots, but it cannot be called great art.

Yoshitoshi’s designs of the mid-sixties often include whimsical touches, the creative flourishes of a high-spirited young man in his twenties, but they are not reflections of a peaceful psyche. Many of the themes are violent, and bloody details abound. Most of the backgrounds are black, and even when some colors are bright—Yoshitoshi experimented with the new aniline dyes that were being imported from Europe—the atmosphere of the prints is somber and brooding.

Political Instability

The economic and political backgrounds against which Yoshitoshi was trying to establish himself were very unsettled. Runaway inflation and periodic crop failures ravaged the 1860s, and life was diffi cult in both the cities and the countryside. In the spring of 1866, Shogun Iemochi led an inconclusive expedition against Chōshū, a province in the extreme west of Japan, whose samurai had shelled his palace in Edo. In July 1866, Iemochi died. The emperor died in December. The winter of 1866 saw nationwide rice shortages, with rice riots erupting in major urban centers. Yoshitoshi’s student, Toshikage, joined the rioters in Edo.

In January 1867, Mutsuhito, a boy of fourteen, was made the new emperor. He became the rallying point of middle-ranking samurai alienated by the failure of the shogun’s government to resist western intrusion. Instead, the West was to be learned from and used—the same

4. Wakan hyaku monogatari, “One Hundred Tales of China and Japan,” 1865. Iga no Tsubone and the ghost of Kiyotaka. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

5. Biyū suikoden, “Handsome Heroes of the Water Margin,” 1866. Takagi Umanosuke and a ghostly head. Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

a policy of expansionism soon emerged. Taiwanese natives massacred some shipwrecked Okinawan fishermen in 1874, whereupon a Japanese force invaded Taiwan and extracted a large indemnity from China. In 1875 a naval force seized Kanghua castle in Korea after a similar provocation; a hero of the wars of the Restoration, Saigō Takamori, and others had resigned from their government posts in 1873 to protest a decision not to invade Korea.

In 1876 the government founded the Kōbu bijutsu gakkō, Technical Art School, where foreign artists were employed to teach western principles of painting, sculpture, and the applied arts. In association with the government’s decision to establish the indigenous Shinto as the national religion, large quantities of Buddhist art were deliberately and systematically destroyed, since Buddhism was regarded as a foreign importation.

There are few examples in history of a complex society experiencing upheaval to such an extreme degree as Japan did in the second half of the nineteenth century.3 Everything was questioned. It was seriously proposed that English be adopted as the national language and that Christianity be made the state religion. The early twentieth-century novelist Natsume Sōseki suggested that “this rapid course of development constituted a nervous breakdown in the Japanese national character.” Yoshitoshi’s own nervous breakdown might be viewed as an analogy. Many people must have been bewildered by such extraordinary changes, even in a pliant, hierarchical society accustomed to obeying what was decreed from above.

Exorcising the Violence

It took time for the recovered, “resurrected,” Yoshitoshi to regain the momentum of the late 1860s. He began 1874 with a series called Keisei suikoden, “Biographies of Drunken Valiant Tigers” (fig. 17). These were members of the shogun’s troops who had died in the recent civil wars, “drunk” on a sense of righteousness and honor.4 The prints are carefully drawn and full of action, but, unlike the “One Hundred Warriors,” distanced from their subjects and less compelling.

Yoshitoshi’s intensity returned in two designs of recent political events, the murder of the shogun’s chancellor in 1860, and the Battle of Fushimi of 1868. By illustrating potentially controversial events directly, rather than by showing parallel historical events, Yoshitoshi was testing the government’s de facto relaxation of the censorship laws; he had, for example, still maintained the fiction in the “One Hundred Warriors,” who were portrayed as figures from the Taiheiki and Taikōki histories. No one knew what offi cial reaction would be if the old regulation was broken, so this was courageous of Yoshitoshi; the new government was sensitive to criticism and some of Yoshitoshi’s work was banned later for various reasons.

Yoshitoshi’s interpretation of the Battle of Fushimi shows a mass of fighting soldiers set against a background of flames and billowing smoke. The design is wild, uncontrolled, filled with panic, unsettling in its red confusion. Yoshitoshi swore to give up his career and leave Tokyo if the design was not a success. His publisher supported him, and his students and mistress prayed to Nichiren, founder of a sect of Pure Land Buddhism. The design struck a chord in people’s minds and sold well enough for Yoshitoshi not to be fatally discouraged.

Yoshitoshi was stirring up memories of terrible events that people may have preferred to forget. Perhaps there is a parallel with the American experience in Vietnam. For a decade after the Vietnam War ended, it was largely ignored by cinema and literature as a subject or as a source of artistic inspiration. People’s reactions to Vietnam were uncomfortable and ambivalent, unlike the Second World War, where issues were largely

17. Keisei suikoden, “Biographies of Drunken Valiant Tigers,” 1874. Umanosuke fighting on a staircase. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

clear-cut. After many generations of peace, people’s reactions to the civil wars associated with the Meiji Restoration may have been equally uncomfortable.

Yoshitoshi took upon himself the burden of exorcising the trauma of recent events by making images of them and presenting them to the public. His importance at this time in Japan’s social history was to bring to the surface the suppressed doubts and latent fears of his countrymen. The disturbed nature of his designs and his nervous breakdown indicate how painful was the process of raising and confronting the specters. Other woodblock-print artists were occupied in designing traditional prints in the old styles or illustrating details of westernization. No other artist of the period tried to cope with the internal, emotional issues of the changes as Yoshitoshi did.

He seems finally to have put his dark memories behind him in a triptych of the Battle of Ueno designed late in 1874 (fig. 18). After this print few of his designs, even prints of warriors, actually show corpses or blood, and the tension in his prints becomes psychological rather than overt. The Battle of Ueno triptych is drawn in a realistic style, a development from the half-western experimentation of the “One Hundred Warriors” of six years before. The drawing is meticulous and the composition more thoughtful than the confused “Battle of Fushimi.” The scene is set late in the day’s fighting, when its individual combatants have become exhausted. One, famished, is eating (compare the warrior eating a rice ball with bloody hands, fig. 9). Rain falls, smoke billows, but without the roar of flames. The battle is almost over. It is time for rest and regeneration.

Newspaper Prints

Newspapers began to proliferate after the Meiji Restoration. In the summer of 1874 a Tokyo daily hired Yoshiiku, the rival of Yoshitoshi’s student days, to design prints of sensational local news stories; the sheets were then issued separately from the newspapers, usually as monthly supplements for subscribers. The following spring a rival newspaper, the Yūbin hōchi shimbun, “Postal News,” hired Yoshitoshi to do the same for them. Over the next eighteen months the paper published sixty of his designs (fig. 19). These prints are of greater social than aesthetic interest. The subject matter is often bizarre, and the designs are stilted, with awkward gestures and exaggerated facial expressions. Nevertheless the prints are lively and energetic.

18. Tōdai sannōzan sensō no zu, “Picture of the Battle of Sannō Hill in Ueno,” 1874. Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

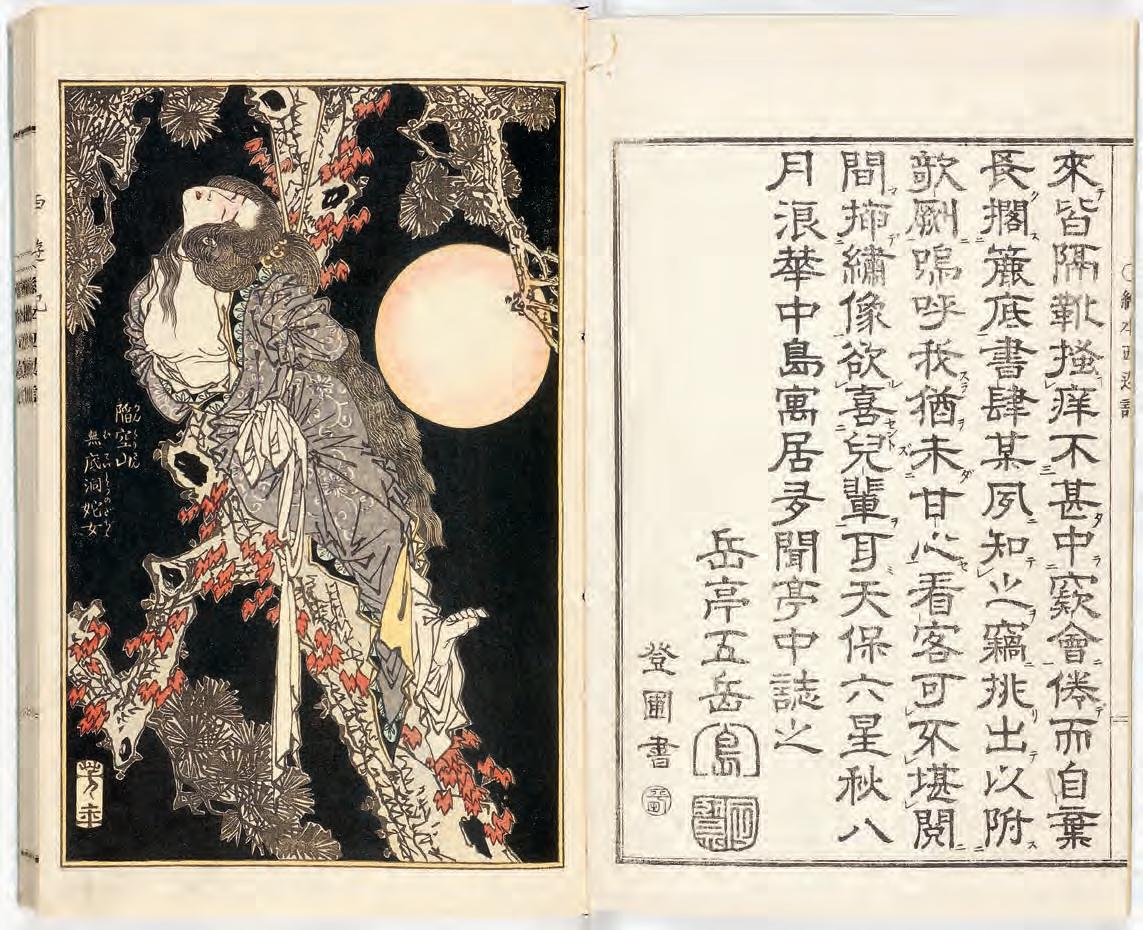

42. Ehon saiyū zenden, “Picturebook of a Journey to the West,” 1883. The demon-woman tied to a tree. Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

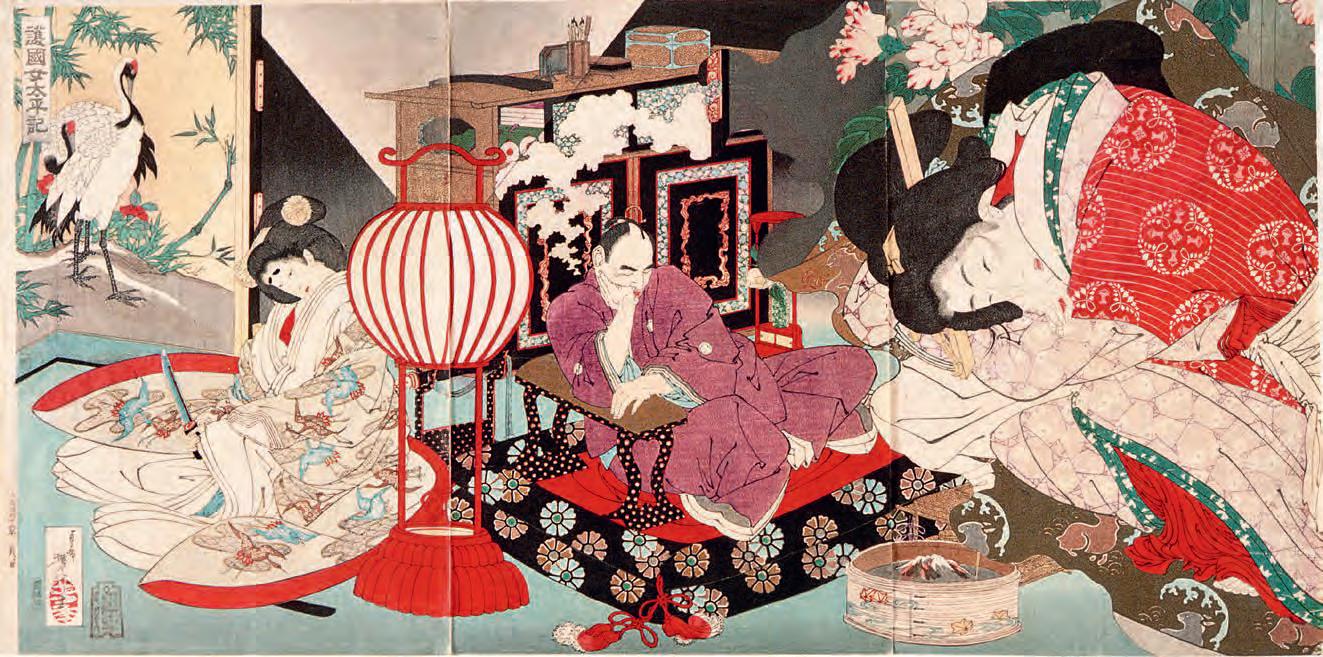

43. Gokoku onna taiheiki, “A Woman Saving the Nation, from the Taiheiki Chronicle,” 1886. Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

which Yoshitoshi had predicted, although the first design (fig. 41) did not sell well initially. “ They’re all blind,” he muttered, as he had when his series Ikkai zuihitsu failed a dozen years before.

In the 1880s Yoshitoshi produced designs for 120 illustrated books, a very large number. After Kyōsai, he was probably the most influential book illustrator of the Meiji period. Japanese illustrated books were small, with texts as well as pictures printed from wooden blocks. Some are delightful gems, but many of Yoshitoshi’s are not. His lines, which burst with nervous energy, are not well suited to the small format of the Japanese book. The agitated, angular figures of many of his book illustrations seem to have been drawn hurriedly to fulfill commissions, though his imagination still occasionally flashes through (fig. 42).

The styles in which Yoshitoshi drew his bijin-e seem to have corresponded to the state of his relationships with women. In 1888, after his marriage to Sakamaki Taiko, he produced Fūzoku sanjūnisō, “ Thirty-two Aspects of Customs and Manners” (fig. 44), his finest prints of women. The series shows vignettes of women from different social classes over the previous one hundred years, caught in typical moments of their quiet lives. Relaxed and serene, the series is unlike any of Yoshitoshi’s previous bijin-e. The women are portrayed sensitively, as individual human beings. However, they are still perceived from a distinctly male viewpoint. The series has a sensual flavor, with many titles containing erotic puns and innuendoes. This is partly a result of the large number of designs that depict geisha, courtesans, and concubines, all occupations that are defined in terms of sex. The passive role of women in a male-dominated society is not questioned. Nor was Yoshitoshi attempting in the series to make a statement about the changing role of women in Meiji society. If he had wanted to make such a statement he would have chosen different subjects for the series: a schoolmistress, a seamstress in a factory, geisha in modern dress.

44. Fūzoku sanjūnisō, “ Thirty-two Aspects of Customs and Manners,” 1888. Strolling: the wife of a nobleman in the Meiji period. Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

50. Detail of plate 68, Nankai no tsuki, “Moon of the Southern Sea.” The female bodhisattva Kannon.

One Hundred Aspects of the Moon: An Introduction

Yoshitoshi was the last creative genius of ukiyo-e. His career spanned two cultures, traditional and Meiji Japan. His values and sensibilities were molded while Japan was still formally cut off from the rest of the world—he was already twenty-nine years old in 1868, when the Meiji Restoration placed Japan squarely on the road toward westernization.

Like most of his contemporaries, Yoshitoshi was fascinated by the world elsewhere, but as the decades passed he became increasingly concerned at how much his countrymen had lost by abandoning their traditions. He therefore took as subjects for his prints stories from Japan’s glorious and colorful past. Though they looked backward in the sense that they illustrated historical events, Yoshitoshi’s prints were revolutionary in their representation of individual human emotion and in their psychological sensitivity. The supreme example is his last great series of prints, Tsuki hyakushi, “One Hundred Aspects of the Moon.”

Tsuki hyakushi is a series of one hundred single-sheet woodblock prints with the moon as its unifying motif. It illustrates a wide range of figures from Japanese and Chinese history, literature, and folklore. Apart from the moon or references to it (the moon is not always visible in the print), the subjects are unrelated.

The first five designs were published in the autumn of 1885. New designs were issued singly or in batches every few months, until the one hundredth was published shortly before Yoshitoshi’s death in the summer of 1892. The series was wildly popular even as it was being produced—people would line up before dawn on the morning of publication to buy

Afamous episode in the semihistorical San guo yan yi, “Romance of the Three Kingdoms,” forms the basis for this design. Written in the fourteenth century, the “Romance” is still widely read in China today. The story unfolds during the civil wars of early third-century China, when the Han empire was breaking up into three separate kingdoms.

The major character in the story is Cao Cao, in Japanese Sōsō. The son of a low-ranking soldier, Cao Cao rose to prominence when he put down a rebellion of the Yellow Turbans in the year 184. Having expelled them from Shandong province in northeastern China, he proceeded to make the area a power base from which he attempted to become emperor himself—he was successful to the extent that one of his sons became the first emperor of the Wei dynasty. He ruthlessly removed anyone who stood in his way, and his life was one of constant treachery and intrigue. Though he is the villain of the “Romance,” he is portrayed as a brave and forceful man, at least as attractive as many of the heroes of the story.

Cao Cao is crossing the Yangzi River on the night before the decisive Battle of the Red Cliffs. He stands in the prow of a boat at the head of 830,000 troops, in full, though anachronistic, Chinese military regalia—Yoshitoshi has captured his powerful stance very well. A following breeze stirs his robes, and mists swirl over the river. The moon rises over the distant cliffs; two crows fly overhead.

The “Romance” describes Cao Cao on the eve of the great battle at a banquet with his generals. He hears crows cawing and asks why they are making such an inauspicious noise in the middle of the night. He is told that they cannot sleep because of the brightness of the full moon. Cao Cao is slightly drunk and brushes off the ill omen. He defiantly brandishes the great spear that he grasps in this design, boasting that it has subdued all his enemies so far, and will do so again. One of his offi cers contradicts him, sug gesting that caution would be wise in their present circumstances. Cao Cao immediately kills him, and the banquet breaks up gloomily. He then gives orders for the impending battle, in which he is defeated.

Most educated Japanese in Yoshitoshi’s time would have been familiar with this chapter from Chinese literature. Over the centuries, a great many Chinese stories had been incorporated into Japanese culture, and Yoshitoshi devotes nearly a fifth of the “One Hundred Aspects of the Moon” to Chinese subjects. He illustrates the Battle of the Red Cliffs again in the series, showing a poet who eight hundred years later visited the site of the battle, where he composed one of China’s most famous poems.

Cao Cao’s name in the title cartouche is written appropriately in square, classical Chinese characters. In China a phrase meaning “Speak of Cao Cao, and Cao Cao comes” is a close equivalent of the English “Speak of the devil.”

Engraver: Enkatsu

Seal: Taiso

Printed: 10.1885

Inabayama no tsuki

This design is taken from the period of civil war that preceded the unification of Japan. In 1564, the military leader Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582) was besieging the Saitō clan in their castle on Inaba Mountain, near Gifu in central Japan. The momentum of Nobunaga’s campaign had been checked by the well-guarded castle, which seemed impregnable. Nobunaga’s young lieutenant, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, learned of an unguarded route into the castle complex and planned a daring assault, for which he chose six of his best men. Tying food around their waists and water-gourds on their backs, they arranged that as soon as they were inside the castle they would raise the gourds high above the walls on bamboo poles as a signal for the troops outside to attack.

Hideyoshi and his men set off late in the afternoon of the thirteenth day of the eighth month, a date indicating an almost full moon. The approach was long and diffi cult, culminating in a perpendicular cliff. This they scaled by the light of a moon so bright that “every bamboo leaf was clearly visible.” The plan went smoothly, and the castle was taken. The story of Hideyoshi’s gourds was a famous one, which Yoshitoshi had illustrated before in a triptych of 1877.

Gifu Castle on Inaba Mountain dominated Mino province. It was built by the Saitō leader, Dōsan, only a few years before Hideyoshi’s exploit. The fortress was the scene of much bitter fighting, and changed hands several times in the last decades of the sixteenth century. It was finally destroyed in 1600 after another long siege, and was never rebuilt—no feudal lord resided at Gifu during the Edo period (1600–1868). Jōkamachi, castle-towns, played a significant but brief role in Japanese military history. They were strategically important during the midsixteenth-century wars of unification, then became obsolete during the long peace imposed by the Tokugawa shogunate.

A huge moon dominates the design, so large that it would have surprised Yoshitoshi’s contemporary audience. The moon backlights susuki grass, combining two of Yoshitoshi’s favorite decorative motifs. It is placed low in the composition to give a sense of weight as the soldier, probably Hideyoshi himself, reaches the top of the cliff. His water-gourd and long katana are strapped to his back. The sword stretches between the moon and the title cartouche, connecting these two light-colored areas and tying the composition together.

While Gifu Castle in Mino province was being taken and retaken, the kilns in the countryside around it were producing the Oribe and Shino ceramics, with their daring designs and irregular glazes, that appear so modern today.

Engraver: Yamamoto Seal: Yoshitoshi no in Printed: 10.12.1885

16. The moon glimmers like bright snow and plum blossoms appear like reflected stars ah! the golden mirror of the moon passes overhead as fragrance from the jade chamber fills the garden —Sugawara no Michizane

tsuki kagayakite seisetsu no gotoshi

baika wa shūsei ni niru awaremubeshi kinkyō tenzu teijō gyokubō no kaori —Sugawara no Michizane

Sugawara no Michizane (845–903) was a statesman at the Heian court. He was a brilliant scholar of Chinese literature and probably the finest of the early poets who wrote in Chinese. He excelled in everything from archery to extempore poems and rose rapidly in rank, serving the emperor Daigo wisely and diligently in a number of important posts.

On the first day of the year 901 there was an eclipse of the sun. His enemies at court used this terrible omen as evidence that Michizane wished to eclipse the emperor. He was exiled to Kyushu and died a lonely death there two years later.

The vengeful fury of Michizane’s spirit was unleashed on those who had slandered him. One by one they died, and the country was torn by extraordinary natural disasters. Then Emperor Daigo also died. The monk Nichizo traveled down to Hell and discussed the situation with the repentant emperor, who posthumously pardoned Michizane and restored his rank. Eventually Michizane was deified, becoming Tenjin, the Shinto god of music, literature, and calligraphy. Shrines are still dedicated to him, and he is particularly helpful to schoolchildren learning to write. In his vindictive form he is a manifestation of the thunder god, scourging slanderers and other evildoers with his thunderbolts. It is in this violent guise that he is usually represented, for instance in a print of 1881 from Yoshitoshi’s series Kōkoku nijūshikō, “ Twenty-four Achievements in Imperial Japan.”

Michizane first showed his literary talents at the age of eleven. Instructed by his father to compose a poem on the beauty of plum blossoms seen under the light of the full moon, he immediately wrote the poem above in classical Chinese form. Chinese was the language of learning and culture in Japan at this time, and the poem in the cartouche here has been written in formal, square Chinese characters. The young poet holds his brush delicately, poised above paper resting on a fan. His hair is in the style of a boy who has not yet celebrated the genpuku coming-of-age ceremony.

The drawing of the gnarled but healthy old plum tree is a tour de force, with the blossoms left in reverse against the background and wide, firm brushstrokes making up the trunk. The trunk has been printed twice, first in gray, then in black—the brushwork has been elegantly reproduced by the engravers. The plum is the first tree to bloom in the spring, sometimes as early as the lunar New Year, and a plum tree is often depicted flowering in the snow. A reference to plum blossoms in poetry or painting indicates that the season is late winter or early spring, with connotations of life bursting forth from apparent deadness, triumphing over adversity.

Michizane had a special affection for plum blossom. His crest was a single plum flower, and many of his poems are about plum. The most famous was written when he was about to go into exile: he tells the plum blossoms in his garden not to forget the spring when the east wind blows but to load it with perfume, even though the master of the house is no longer at home. There is a legend that, in his deified form, Michizane went to China to study Zen Buddhism, returning with a flowering plum branch to signify the awakening of spring. He came to represent a harmonization of Shinto learning with Zen directness, and was a favorite subject for painters of various schools, including Zen. Yoshitoshi’s choice of subject, however, Michizane as a boy, is unusual.

Engraver: Yamamoto Seal: Taiso Printed: 1.1886

29. The Yūgao chapter from “ The Tale of Genji”

Genji yūgao no maki

One of the most delightful of the series, this design is taken from Genji monogatari, “ The Tale of Genji.” Genji is Japan’s, perhaps the world’s, first novel. It was written by a woman, Murasaki Shikibu, who belonged to the elegant world of the eleventh-century Heian court. Murasaki is shown elsewhere in the Moon Series, inspired by the beauty of the moonlight as she begins to write her novel. It describes the amorous adventures of Genji, a supremely handsome young prince of great aesthetic sensitivity, who has a succession of love affairs with a number of beautiful women.

The most mysterious of Genji’s lovers was a young lady who lived in a dilapidated house surrounded by a desolate, overgrown garden. Such wild places were not uncommon in Kyoto, where a relatively small population lived in a large area in which wild beasts still roamed. Passing by the house one day, Genji noticed lovely white flowers growing luxuriantly over it. The flowers were called yūgao, literally “evening face,” the evening equivalent of asagao, morning glory. Genji sent his servant to the house to ask for a few flowers, and the lady’s servant presented them on a fan on which a poem had been written in an elegant calligraphy. On the basis of this handwriting, a love affair was initiated between Genji and the mistress of the house.

Wraithlike, not conforming to the normal standard of Heian beauty, which in the Chinese Tang tradition was distinctly chubby, the lady fascinated Genji. She refused to tell him her history or her name, so he called her Yūgao after the flowers. Eventually she accepted his invitation to visit one of his lavish villas, where they consummated their delicate passions. She died within a few hours, fading as quickly as a yūgao flower, killed by the jealous spirit of one of Genji’s former mistresses. Genji mourned her more deeply than he did most of his lost loves.

Here Yūgao’s ghost wafts wistfully through her garden on a night of the full moon: yūgao is known also as “moonflower.” Flowers and vines show through the ghost’s transparent body. Her figure seems to have no volume, as if projected onto a surface, like a screen. The shade of blue used for Yūgao’s eye and lips is subtly different from that used for the background wash, making them stand out without overemphasizing them; blue lips were a convention to indicate a person who was dead or dying. Also highlighted are the yellow centers of the flowers; in the original print the white petals are embossed. The gourd is shaded on one side to give an impression of roundness. The colors have been beautifully printed to shade into nothingness at the bottom of the picture.

The vegetation reminds one of art nouveau drawings and posters in Europe, which were influenced by contemporary Japanese art. Yoshitoshi loved the burgeoning life of plants, and his designs often include leaves and tendrils. Noguchi Yone commented on this when he presented Yoshitoshi’s work to the West for the first time in a lecture to the London Japan Society, citing this design as an example.

Engraver: Yamamoto

Seal: Taiso

Printed: 3.1886

Kitayama moon —Toyohara Sumiaki

Kitayama no tsuki —Toyohara Sumiaki

Toyohara Sumiaki taught music at the court of Emperor Go-Kashiwabara (reigned 1500–1525). He liked the spontaneity of impromptu music making and used to play flute duets with strangers, as did Hiromasa. One night, enchanted by the beauty of the moonlight, he wandered onto the moors of Kitayama, north of the palace. Suddenly he found himself surrounded by a pack of wolves. Assuming that he was about to die, he played his favorite tune for the last time. To his amazement, the wolves became spellbound by the music, first lying down to listen, then returning to the woods. Sumiaki made his way back to the palace and lived on to the age of seventy-four.

Sumiaki carries a flute and wears a brocade robe and his black hat of offi ce. The way the cloth wraps around him, in sympathy with his gesture of fear, is typical of the way Yoshitoshi intensifies mood through the details of his designs—there is more than the wind at work in the movement of this heavy fabric. Susuki grasses echo the robe’s movement, besides indicating the wildness of the moors. The moon stares balefully through a gap in the clouds—it is not friendly. In later impressions the sky is sometimes printed an ominous red color. The moon has a raised, unprinted edge left in relief, accented by the lightest of gray shadows, while deep black shadows edge the clouds; the treatment is striking and sophisticated. The drawing of the two wolves is taken directly from a book illustration by Kuniyoshi, Yoshitoshi’s teacher.

Sumiaki came from a long line of music instructors—one of his ancestors was Toyohara Tokiaki, whose story is included later in the series. The family specialized in teaching the shō, a form of reed mouth organ with a plaintive sound. Sumiaki began studying music with his father at the age of seven, and by the time he was twenty was considered to be an accomplished musician. In 1511 he became personal music tutor to the emperor Go-Kashiwabara, and in 1518 he was appointed gagakugashira, head of court music. Gagaku, literally “elegant music,” is the name given to the ancient music and dance of the Japanese court; its roots lie in Tang China (618–907), with possible earlier connections to the Middle East.

Sumiaki was the epitome of an accomplished gentleman. He was expert in the art of tea before the cult became widely fashionable, and built a humble tea hut under a pine tree in his garden. A talented poet, he studied poetry with the master Sanetaka. He was a devout follower of the Nichiren sect of Buddhism. When he died, in 1524, he left an extensive collection of poems and a thirteen-volume work on musical theory.

Engraver: Yamamoto

Seal: Taiso

Printed: 5.6.1886

59. In the moonlight under the trees a beautiful woman comes getsumei rinka bijin majiru

Aconventionally beautiful woman dressed in luxurious Chinese costume stands by a flowering plum tree under a perfectly full moon. She is the Spirit of the Plum Tree, who appeared to Zhao Shixiong, a Chinese poet of the Sui dynasty (589–618). One fresh spring morning, Zhao climbed the slopes of the sacred mountain of Luofu in southern China to admire the flowering plum trees there. As evening drew on, he fell asleep under the trees, and a nymph appeared to him in a dream. Waking in the magical light of a full moon, he realized that the Spirit of the Plum Tree had visited him, and wrote a poem about his experience.

The subject became a popular theme in Chinese painting, and was later taken up by Japanese literati painters. It was revived as a theme in Yoshitoshi’s time by artists of the Nihonga, “Japanese pictures,” movement, who called the Spirit of the Plum Tree Rafusen, “Fairy of Luofu.” This design is also reminiscent of Kyoto-style paintings of Chinese beauties that were popular in the eighteenth century.

The figure here has a double chin in the sturdy tradition of Chinese feminine beauty associated with the Tang (618–907). Her outer robe bears a heavily embossed pattern. This embossing is called karazuri, “blind printing,” often translated as gaufrage, a reminder that many early connoisseurs of Japanese woodblock prints were French. The effect was achieved by laying the nearly completed print, slightly dampened, face down onto a block carved with the required pattern. The back of the paper was then rubbed either with a baren, a bamboo-leaf pad, or a curved piece of ivory, such as a boar’s tusk.

The gauze fan is purely decorative, as the night is not warm—plum trees bloom in late winter or early spring, and the lady is wearing several layers of clothing. The colors of the robes are combined in unusual ways, which would have given an exotic “Chinese” flavor to the print. The colors are soft and muted in the moonlight, with the exception of the bright red of the ornament in the lady’s hair, her lip, her sash, and the whisk at the end of her fan (and of course Yoshitoshi’s seal). These touches of red do not dominate the design but highlight it, and the atmosphere of the print remains one of a sophisticated opulence. The sheen of the lady’s oiled hair is suggested by the grading of shades of black and gray. With a little imagination one can almost smell the heavy perfume of the lady’s clothes mingling with the sharp fragrance of the plum blossoms.

The seven characters in the cartouche make up a line of Chinese poetry. Japan imported its writing system from China in the seventh century; as a result, Japanese characters usually have two or more readings: the native Japanese, plus a Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese original. For example, in the titles of the prints in this series, the same character for moon has sometimes been transliterated as getsu (derived from one of several Chinese pronunciations of the character for moon), sometimes as tsuki (the Japanese word for moon). Japanese compound words normally require the Chinese-derived pronunciation, but sometimes the choice is a matter of taste. Since the subject of this design is Chinese, there would have been a tendency to pronounce the title here in a sinified manner.

Engraver: Yamamoto

Seal: Taiso

Printed: 15.3.1888

Published: 19.3.1888

80. Moon of the filial son —Ono no Takamura

kōshi no tsuki —Ono no Takamura

Ono no Takamura, an offi cial at the Heian court during the ninth century, is identified in the title cartouche as the figure in this design. After a series of early promotions, the young Takamura was chosen to join an offi cial embassy to Tang China. A disagreement occurred over which ship he was to take, and Takamura petulantly resigned from the mission. He was exiled for this impertinence, but composed a poem that gained sympathy for his action. After a year he was recalled and continued his offi cial career. He died in 852 at the age of fifty.

When he was young, Takamura lived with his father, a provincial lord northeast of Kyoto, where his education was neglected. It was not until he was sent to the court, where he was noticed and encouraged by Emperor Saga, that he began his studies. Takamura was a magnanimous man who would often share his offi cial salary with relatives and friends less fortunate than himself. He was always respectful toward his parents, though the histories cite no particular examples of this.

Instead, this design includes the iconography of the story of Ceng Shen, called Sosen in Japanese, who was one of the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety in China. The story of Ceng Shen was well known and fits the image so appropriately that Yoshitoshi probably had it in mind when he designed the print.

Ceng Shen (506–437 b c .) was an important disciple of Confucius. While gathering brushwood in the forest one day, he suddenly became acutely aware that his mother needed him. He hurried home, and found that his mother had missed him so intensely while entertaining a visitor that she had bitten down hard on her finger in vexation. This was suffi cient to ensure Ceng Shen literary immortality—he is generally credited with compiling the list of the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety, in which on the strength of this small incident he included himself.

Two other stories from Ceng Shen’s life show the extremes to which the regard for filial piety was taken in China at this time. He was weeding the family melon patch one day, when he accidently cut through the roots of one of the melon plants. For this, his father beat him senseless. When Ceng Shen told Confucius about the incident many years later, Confucius reprimanded him for not running away, since his father might have killed him, and to allow that to happen would not have been acceptable filial behavior. Later Ceng Shen divorced his wife because she served his mother badly cooked pears.

Here the filial son looks up from binding kindling wood, alert to his parent’s need for him. The valley between him and his home is filled with mist, and a misty halo surrounds the moon, elements of Chinese landscape painting that add a Chinese aura to the design. Note the different styles of brushwork that Yoshitoshi has used to emphasize the human subject: figure and robes are delineated by fluid, calligraphic lines, beautifully drawn, while brushwood, trees, and huts are made up of thicker, more abrupt strokes.

Engraver: not given Seal: Taiso Printed: 1889