CONTENT

Foreword

Patrick van Mil

‘Like Birds, they Alighted in Bergen’

Marjan van Heteren

‘Fame from North to South’

The Reception of Vincent van Gogh, 1888-1920

Chris Stolwijk

Symbolist, Post-Impressionist, Cubist, Traditionalist

The Reception of Paul Cézanne in the Netherlands, 1890-1930

Maaike Rikhof

Henri Le Fauconnier, ‘Trait d’Union’

Anita Hopmans

Van Gogh, Cézanne, Le Fauconnier & the Bergen School

Marjan van Heteren

The Modern Sensibility and the Picture, 1912

Henri Le Fauconnier

The New Art of Painting, 1916

Piet van Wijngaerdt

Notes

Henri Le Fauconnier, Abundance , 1911 (detail fig. 108)

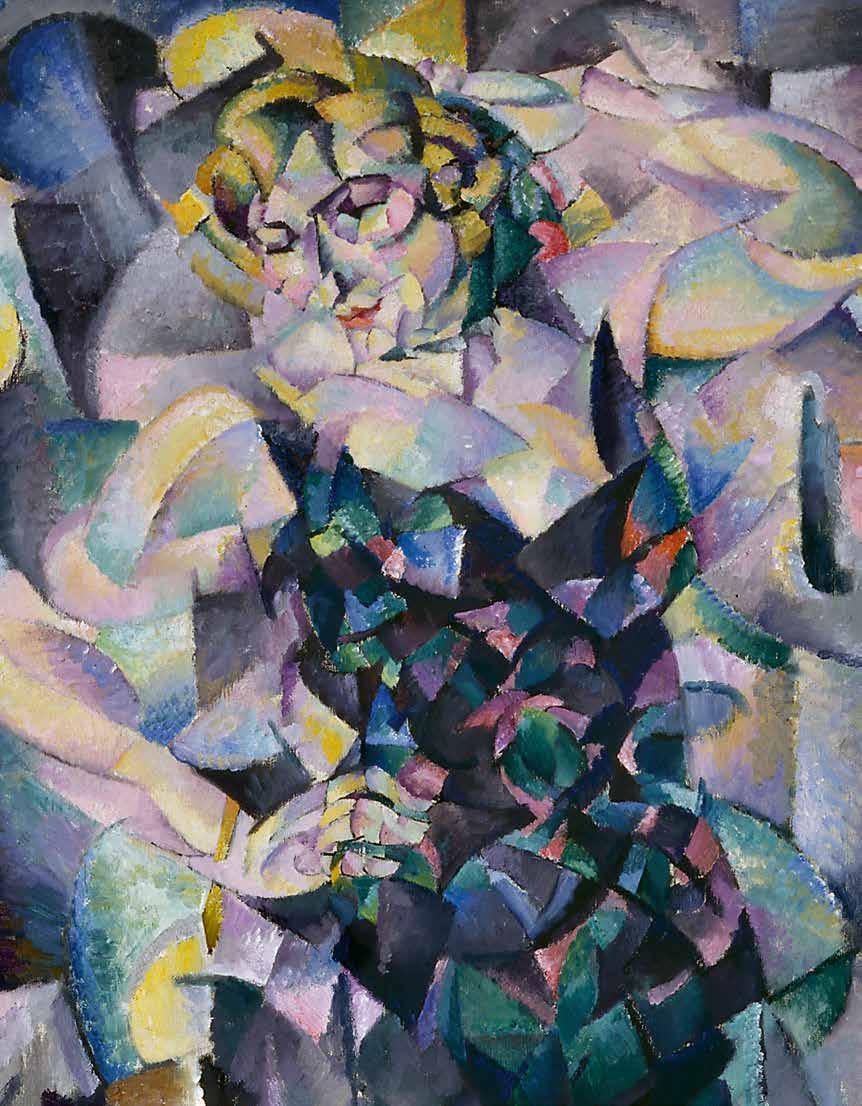

Leo Gestel, Cubist Female Figure (Standing Woman) , 1913 (detail fig. 107)

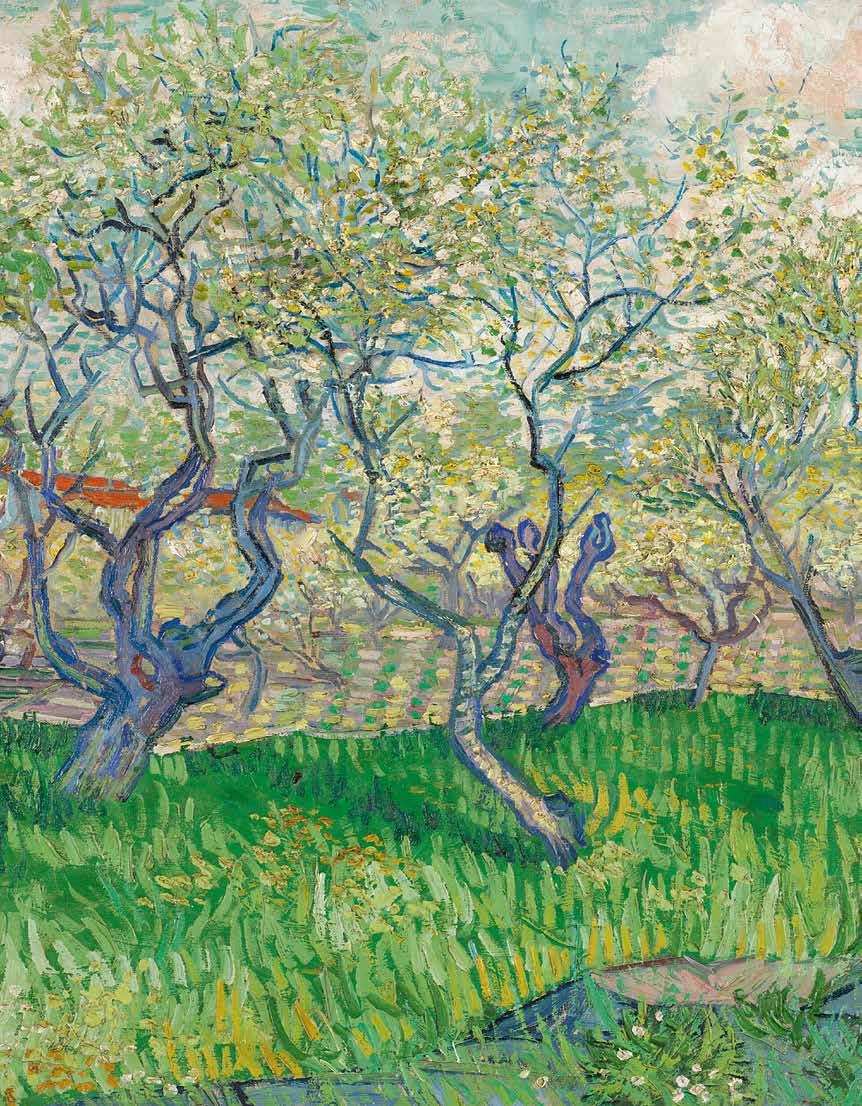

Vincent van Gogh, Orchard in Blossom , 1889 (detail fig. 81)

Van Gogh was not only a ‘veritable realist’ by transcending the depiction of an unenlightening, flat reality in his paintings, but above all a ‘symbolist’ who could translate the Idea into symphonies of colour and form. In addition, Van Gogh combined masculine creative power with feminine sensitivity and hysteria. Summarising, Aurier concluded that Van Gogh’s work was far too complex to be understood and appreciated by the average (bourgeois) audience, let alone that it would be willing to pay a reasonable price for it.

In addition to the six paintings shown at Les Vingt, Theo selected four more canvases on behalf of his brother, at that time in an asylum in Saint-Rémy-deProvence, for the exhibition of the Indépendants in March-April 1890. The ensemble made an even deeper impression than the works from the preceding years. Previously used qualifications such as ‘powerful expression,’ ‘strong effects’ and ‘exuberant use of colour’ recurred in various reviews.14 In addition, Van Gogh’s (alleged) mental health and state of mind – his ‘tortured soul’ and his ‘tormented genius’ – were now included in the discussions of his art. Such characterisations strongly coloured the reception of Van Gogh for several decades.

Early Recognition

Van Gogh died barely three months after the last, successful presentation at the Indépendants in spring 1890. In the months following Van Gogh’s demise, his younger brother Theo, who had been the manager of the Paris branch of the influential art dealer Boussod, Valadon & Cie. on Boulevard Montmartre since 1881, Theo’s brother-in-law Andries Bonger (1861-1936), who lived in Paris, and his artist friend Émile Bernard (1868-1941) devoted themselves to the artist’s legacy. After attempts to organise an exhibition, including a failed one at the well-known art dealer Durand Ruel, a presentation finally took place at the end of 1890 in Theo and Jo’s (former) Paris apartment. ‘On that cold, short Christmas afternoon, while the hordes took pleasure in crowding in front of the garish displays of stalls on the boulevard, a few Dutch people gathered in the gloomy rooms of a temporarily uninhabited house in Montmartre and admired a few hundred paintings. Their enthusiasm was laced with sadness: the art treasure scattered about the uncomfortably cold room was the legacy of an artist who died too soon, whose younger brother – now seriously ill himself as a result of that loss and transported to his fatherland to seek recovery – had been compelled to leave this great relic that was so dear to him to others, albeit in good care. […] It would have been nice if the country could also have seen the peculiar art of Van Gogh and become acquainted with a talent thwarted from reaching full maturity [...],’ De Meester reported.15

Although Bonger and Bernard saw a future in France for the work of this ‘peintre Hollandais’ previously characterised as exuberant – according to Bernard, Van Gogh’s talent was even ‘eminently French’ (‘eminament Français’) – Jo decided to bring all the works from the estate of her brother-in-law Vincent and her husband Theo to the Netherlands. She felt that this, in fact, was where the future lay: for Vincent’s work, for her and for her son Vincent Willem.16 In connection with the settlement of the estate and the shipment of (large parts of) this ‘family collection’ to the Netherlands in the spring of 1891, Andries Bonger, possibly in collaboration with Bernard, compiled a Catalogue des oeuvres de Vincent van Gogh listing 364 paintings; a catalogue of Van Gogh’s works on paper is still missing.17

Jo’s decision to transfer Van Gogh’s works to the Netherlands and her activities in the following years to promote them meant that the early reception and appreciation of Van Gogh’s efforts were twofold. In France, Belgium and later Germany, there was a strong emphasis on Van Gogh’s ‘French’ works. These were seen as an endorsement of his contribution to the development of a ‘modern’ international movement in art and painting based primarily on French principles. In the Netherlands, on the other hand, attention was paid to the artist’s putative Dutch roots, and an attempt was made to place the artist in a Dutch tradition of painting.18

Outside of the Netherlands

In February-March 1891, Les Vingt in Brussels exhibited fifteen paintings and seven drawings with motifs from Provence during their eighth group exhibition in memory of the Van Gogh brothers. Most of the works were loaned from the family collection. On 5 February 1891, a mere two weeks after Theo’s death, Octave Maus (1856-1919), secretary of Les Vingt, wrote to Jo about these works: ‘My friends at Les Vingts and I greatly admire poor Vincent’s art, so personal and so robust.’19 Through Maus, a drawing, Olive Trees, Montmajour was sold to patron and collector Baron van Cutsem. 20

As in the previous year, most of the works that were first exhibited in Brussels were then also shown by the Indépendants in Paris. During their seventh group exhibition in March-April 1891, these colleagues commemorated their ‘peintre Hollandais,’ felled so suddenly in July 1890, by presenting ten of his works made in the southern Provence on a subdued black cloth background. These could thus be distinguished at a glance among the many hundreds of entries. Van Gogh’s canvases were very well received. According to one viewer, ‘universal acclaim’ (‘la gloire universelle’) awaited the artist, a glory that radiated to all contemporary French painting. Partly due to his association with Delacroix (1798-1863), Monticelli (1824-1886), Millet (1814-1875) and Monet (1840-1926), Van Gogh could even be called more ‘French’ than ‘Dutch.’21

Henri Le Fauconnier, The Huntsman , 1912 (detail fig. 114)

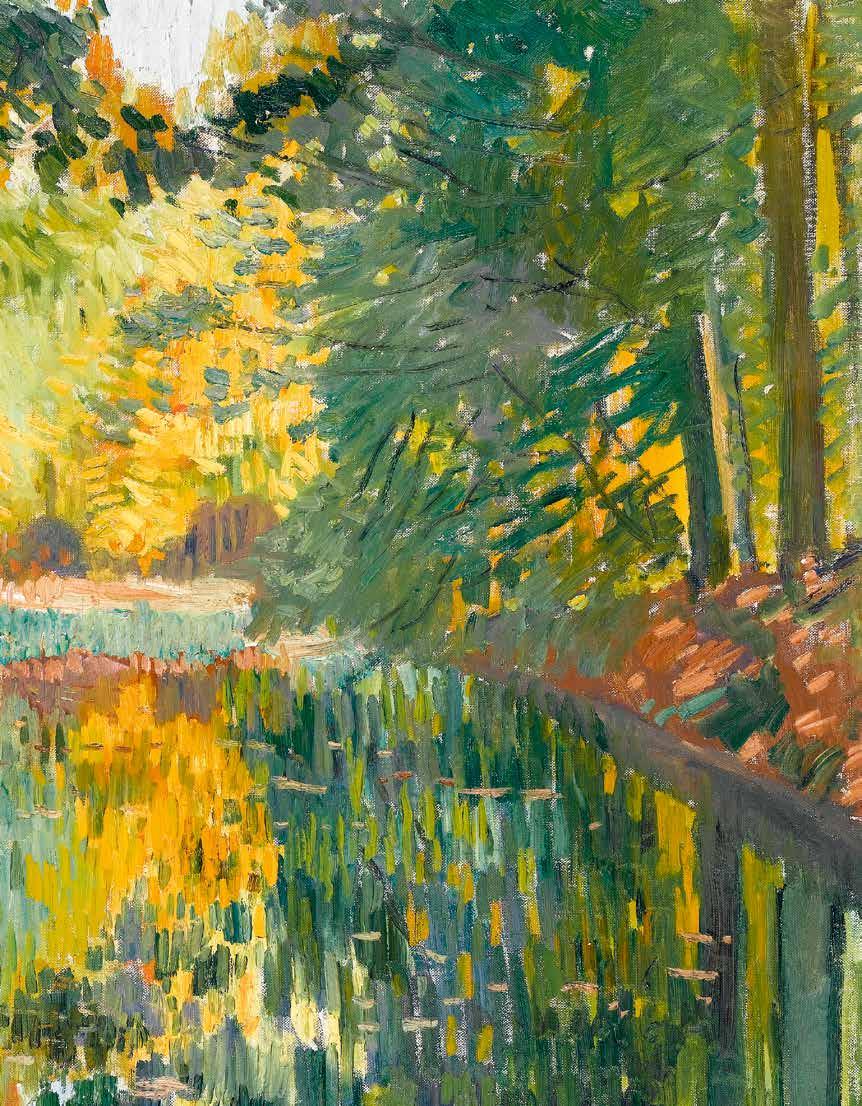

Willem van Blaaderen, Pond in Oud-Bussum , 1913 (detail fig. 99)

Gerrit

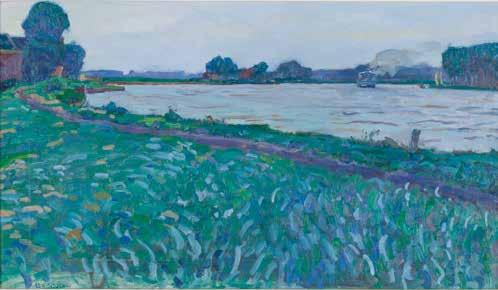

82 Leo Gestel, Amstel, Stormy Weather, 1908.

Canvas, 36.5 x 62.5 cm. Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amersfoort

< 83 Vincent van Gogh, Plain near Auvers, 1890.

Canvas, 73.5 x 92 cm. Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen / Neue Pinakothek, Munich

> 84 Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch, Peat Bog in Stormy Weather. Marouflé, 27.6 x 40.2 cm. Private collection, formerly Simonis & Buunk, Ede

85 Arnout Colnot, Egmond Lake, c. 1910.

Canvas, 60.5 x 86 cm. Museum Kranenburgh, Bergen

> 86 Jaap Weijand, Damlander Mill at Bergen, 1909.

Canvas, 35 x 30 cm. Singer Museum, Laren, gift of Renée Smithuis

recognition, although Kickert noted that in the field of modern art, the Netherlands was still lagging some twenty years behind France and Belgium.30 Colnot’s Egmond Lake dates from this period, as does Basket of Potatoes, which he exhibited at the Sint Lucas artists’ association in the spring of 1911 [figs. 85 and 91].31 The latter small painting is strongly reminiscent of Van Gogh’s still lifes of baskets of potatoes that he made in Brabant in the autumn of 1885 [fig. 92]. Knowing that he would have difficulty selling these paintings, Van Gogh was keen to improve his skills and learn how to render well the texture of potatoes in different shades, seeing this as a useful exercise.32 Four years later, in Arles, he made a version in which he abandoned the pursuit of a realistic representation and correct perspective [fig. 93]. Colnot, who could have seen both the realistic Brabant versions and the colourful French version at the 1905