Heads

‘I saw superb figures out in the country –striking in their expression of soberness. ’

‘I saw superb figures out in the country –striking in their expression of soberness. ’

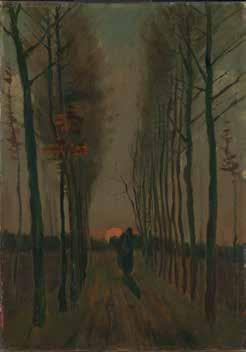

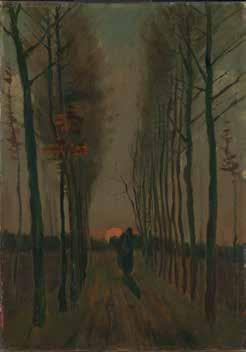

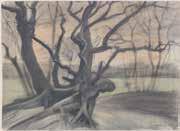

Tree roots in a sandy ground (‘Les racines’)

The Hague, April-May 1882

Pencil, black chalk, brown and grey wash, and opaque watercolour on paper

51.5 x 70.7 cm

Kröller-Müller Museum Otterlo

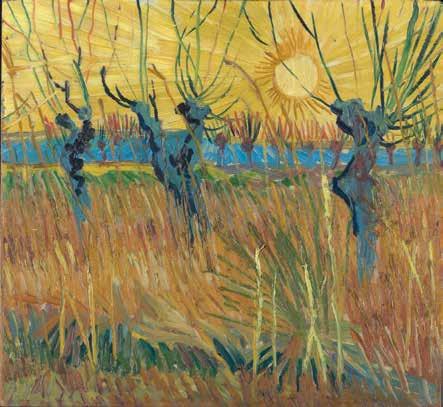

Swamp with water lilies, Etten, June 1881

23.5

In one of the first letters that Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother from Nieuw-Amsterdam/Veenoord, he told him that he had been walking around the place for a couple of days, and his first impressions were very positive: ‘What I find beautiful is everywhere here. That’s to say, there is peace here.’80 He not only found peace and harmony, there was also drama in the landscape. He gave the example of a scene he had come across: ‘Yesterday I drew decaying oak roots, so-called bog trunks (being oak trees that have been buried under the peat for perhaps a century, over which new peat has formed – when the peat is dug out these bog trunks come to light).’

Bog trunks are known in Drenthe as ‘kienstobben’. They are ancient remains of tree trunks that have been preserved in the peat. The trunks that Van Gogh saw probably did not come from oak trees, but from conifers, which were much more common. The structure of the roots suggests the same.81 Peat workers encountered them as they were digging and they had to be removed before they could continue.82 As can clearly be seen in this drawing, they were simply thrown onto a heap.

It was precisely this scene that attracted Van Gogh: ‘These roots lay in a pool in black mud. A few black ones lay in the water, in which they were reflected, a few bleached ones on the black plain. A little white track ran alongside it, behind it more peat, black as soot. Then a stormy sky overhead. That pool in the mud with those decaying roots, it was absolutely melancholy and dramatic, just like Ruisdael, just like Jules Dupré.’

The reflection of the roots in the muddy pool and the stormy sky produced theatrical effects which he tried to capture in his drawing. The labourers in the background are merely extras; the roots are the stars here.

Tree roots feature in other work by Van Gogh, including the early drawing Tree roots in a sandy ground of 1882 and work produced towards the end of his life (his final painting Tree roots, from 1890). The irregular shapes of roots were an endless source of fascination to him. Some have associated them with his troubled mind.

In a review in the NRC newspaper in 1903 the Drenthe drawing was described as: ‘the landscape with the tangled roots of felled trees. Those tangled masses in the watery earth, they speak as if they were people.’83 The grotesque shapes of the bog trunks in this drawing are a gloomy sight in the bare landscape. They evoke the many myths associated with the peat moors, as a place where mysterious sacrifices were made long ago, and where ‘Witte Wieven’ (the spirits of ‘wise women’) and ghosts roam. The stumps survived for many hundreds of years, hidden deep in the peat. Now they were simply cast aside as obstacles. Van Gogh drew a similar open marshy landscape with a high horizon in muted sepia tones in Etten, too.

A woman with a wheelbarrow walks along the country lane towards two men holding digging tools. They recall the 1882 drawing made in The Hague, Boy with a shovel. In the distance we see women stooping over as they work the land, who return as the main characters in the painting Two woman on the peat moor. The female figures, in particular, seem to float in the landscape. Nor is the scale of the figures correct in relation to the foreground.84 Van Gogh added them later. He roughly outlined the drawing on the spot and worked out several of the details later, back at his lodgings.85

This work was left at his mother’s and, having spent time in private collections in the Netherlands, ended up in the collection of John Goelet in New York. He gave it to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in 1975.

Boy with a shovel

The Hague, OctoberDecember 1882

Pencil, pen and black ink (faded to brown in places), black lithographic chalk, white and grey opaque watercolour, and traces of squaring on paper

49.2 x 27.4 cm

Kröller-Müller Museum

Otterlo

Vincent van Gogh executed this image of The peat barge rapidly, with self-assured brushstrokes, completing the entire work in one go: first the figures, then the land and water, and finally the sky.115 The equipment he used included a broad brush and a palette knife. He did not wait until the paint had dried, but painted wet-on-wet. This shows the progress he had made as a painter. Van Gogh was enjoying increasing success in his attempts to capture in paint the images he wished to portray. In the case of this painting, the image was that of a hardworking woman and man hauling peat. Details are irrelevant. The key thing is the essence of the hard life of the country folk, and also the purity of living in harmony with nature. As a critic reviewing an exhibition in Groningen in 1904 remarked: ‘A simpler theme is almost impossible to imagine […] it is nothing more than the barge against the side and the two small human figures, but what he has managed to achieve in this!’116 The faces of the two figures cannot be seen. They are both entirely absorbed in their work. The wheelbarrow is a symbol of human labour and the hard country life. It is a popular element in Van Gogh’s work.

There is movement and action in the painting, as if we can see the wheels of the heavily laden barrow rolling along the sandy path, and hear the woman sighing as she stacks the peat on the barge. The tarpaulin lies ready to cover the load. Van Gogh achieved this dynamism through the diagonal lines in the landscape: the winding path, the steep narrow gangplank and the position of the barge. The woman’s white cap catches the eye in the otherwise dark peat boat. Along with the red of her jacket, it balances the dark lower section of the painting with the lighter colours of the sky above.117

We have a fairly precise idea of when Van Gogh made The peat barge, as he not only mentioned it but also sketched it in his letter of 22 October from NieuwAmsterdam/Veenoord: ‘These were peat loaders, but I’m afraid the scratches are absolutely indecipherable.’118 Since the season for cutting peat was over, this was probably a winter stock of peat for small-scale use. Such a job would generally involved three ‘krooiers’ (men with wheelbarrows) and a ‘loegster’ (a woman who stacked the peat on the boat).119 It would take most of the day to fully load the boat. The peat would be kept on a field where it was left to dry, and taken from there to the boat. In the background, on the right, there seem to be two heaps of peat and a sod hut or other structure.

The peat barge is one of the pieces that Van Gogh left with his mother. It eventually ended up, via Kunstzalen Oldenzeel, with Rotterdam shipowner William Smith and his wife Griettie Smith-van Stolk, who took lessons with Van Gogh expert Hendricus Petrus Bremmer. Bremmer may have arranged the purchase, as suggested by the label on the back of the work, dated 1906, where he verifies in writing that this is an authentic Van Gogh.

In the early twentieth century changes were made to the little tree in the top left.120 It was overpainted at some point, and later restored. The ‘fence’ to the left of the tree was not painted by Van Gogh, and does not appear in the sketch in the letter. It was probably erroneously added during a restoration, as it coincides with the struts of the frame.

For years, the painting was in the possession of the Van Hoey Smith family. It was purchased by the Drents Museum in 1997, and became one of the highlights of its collection.