Tokyo versus Neo-Tokyo: Aida Makoto and Yamaguchi Akira as Urban Visionaries

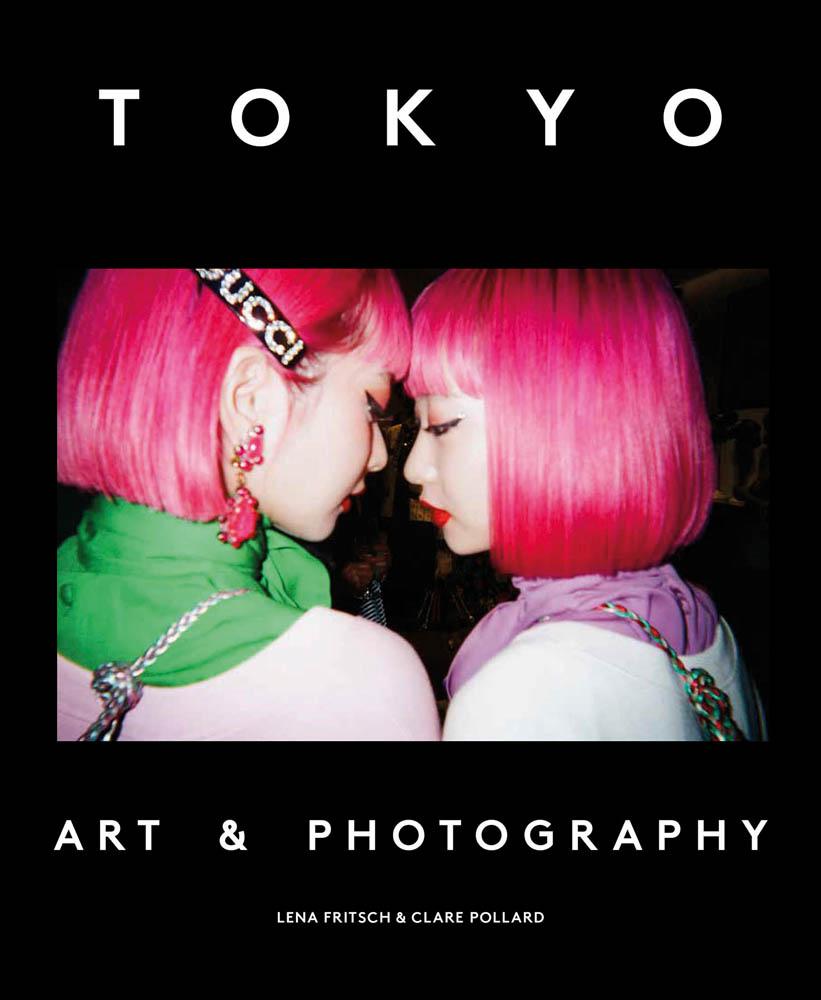

This book and exhibition have depended on the generous support of many individuals and institutions. It is impossible to name all of those to whom we owe a debt of gratitude. Above all, however, we would like to thank the artists, photographers and photographic subjects who have agreed to participate in our project, patiently answering our questions about their relationships with Tokyo and generously sharing images and information: Aida Makoto, AMIAYA, Chim↑Pom, Hosoe Eikoh, Enrico Isamu Oyama, Kanemura Osamu, Kitai Kazuo, Koizumi Meiro, Machida Kumi, Matsui Fuyuko, Moriyama Daidō, Miyamoto Ryūji, Mohri Yuko, Murakami Takashi, Ninagawa Mika, Nishino Sōhei, Satō Tokihiro, Takano Ryūdai, Tanaami Keiichi, Tokyo Rumando, Tsuzuki Kyōichi, Yamaguchi Akira, and Yokoo Tadanori.

Exhibitions rise and fall with the generosity of lenders. To all private collectors, artists and institutions we express our deepest appreciation: Akio Nagasawa Gallery | Publishing; Anish Shonpal; Annet Gelink Gallery; Bodleian Library; British Museum; Chester Beatty Library, Dublin; Chim↑Pom and Mujin-To Production; Ebi Collection; Ibasho Gallery; Japanese Gallery, Angel, London; Khalili Collection; MAD Mason; Matsui Fuyuko; Michael Hoppen Gallery; Mizuma Art Gallery; Mizuno Art Foundation; NANZUKA; the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; Nihon Gallery, Tokyo; Nihon no hanga Museum, Amsterdam; Nishimura Gallery; Pitt Rivers Museum; Rijksmuseum fur Volkenkunde, Leiden; Roland Angst and only photography; Sainsbury Institute; Taka Ishii Gallery; Tate; David Thatcher; Tomio Koyama Gallery; Tokyo Photographic Art Museum; Tsuzuki Kyōichi; Victoria & Albert Museum; Yuko Mohri Studio; Yumiko Chiba Associates; Y collection; Zen Foto Gallery and those who wish to remain anonymous.

We would like to express our sincere thanks to the many supporters of the exhibition and book. We are particularly grateful to Mr Hiroaki and Mrs Atsuko Shikanai for their exceptional generosity and would also like to thank Ishibashi Foundation, White Rainbow, Pictet & Cie, Japan Foundation, Toshiba International Foundation, Suntory Foundation, Gillies McKenna and Ruth Muschel, J Paul Getty Jr General Charitable Trust, The Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation, The Daiwa AngloJapanese Foundation, Giles and Vanessa Campion, Nomura Foundation, The Poleberry Foundation and The Japan Society.

At the Ashmolean, we would like to thank Byung Kim for the insightful exhibition design and Catriona Pearson for managing the logistics. We would also like to thank Director Xa Sturgis for his belief in this project. Aisha Burtenshaw and her team of registrars have shepherded the loans, and in Development we are grateful to Emily Magnuson and her team. Many thanks go to Dec McCarthy, Head of Publishing and Licensing, for working closely with us on the successful completion of this challenging publication. We also thank all the catalogue authors who have responded with diverse new readings of the arts of Edo and Tokyo, and Lucy Fleming-Brown, Kiyoko Hanaoka, Joe Hazell and Joyce Seaman for their research input and invaluable assistance throughout the project. Thanks also to Graham Curtis, David Thatcher and Ellis Tinios for their expert advice. The elegant design of this book is down to Sarah Boris, and we are grateful to Catherine Bradley for the careful copyediting. As always, we thank our wonderful colleagues in Art Handling, Commercial, Communications, Conservation, Design, Education and Interpretation, Exhibitions, Marketing, Press, Public Programmes, Social Media, Visitor Experience, and Benugo Ltd for their skilful work behind the scenes.

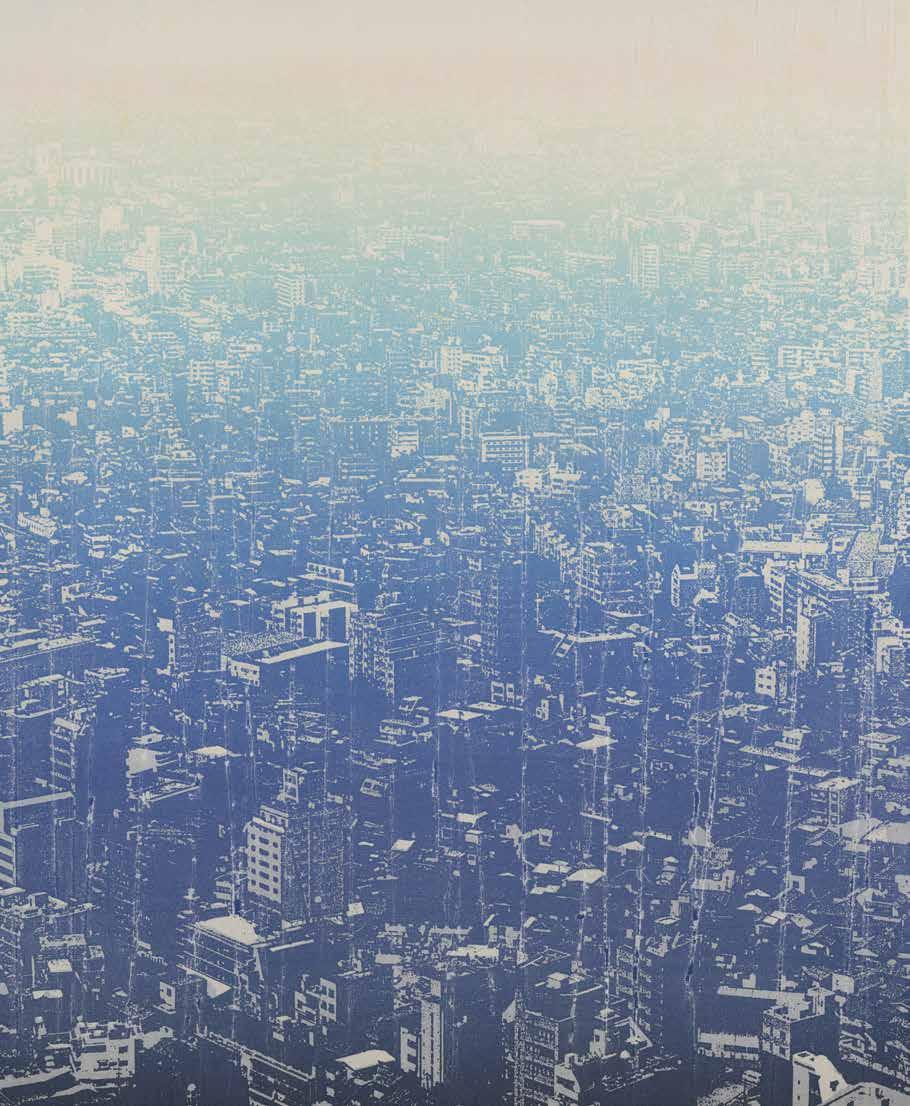

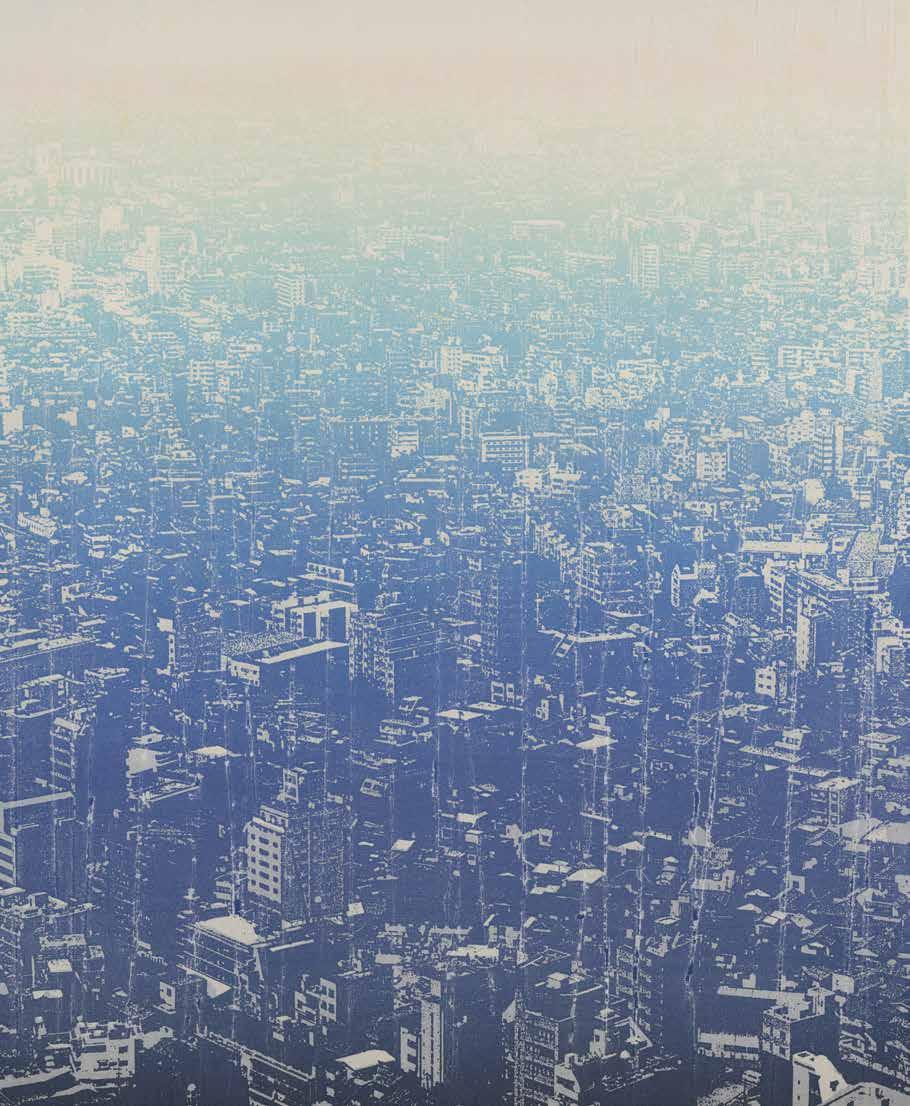

Enrico Isamu Oyama, digital drawing for FFIGURATI

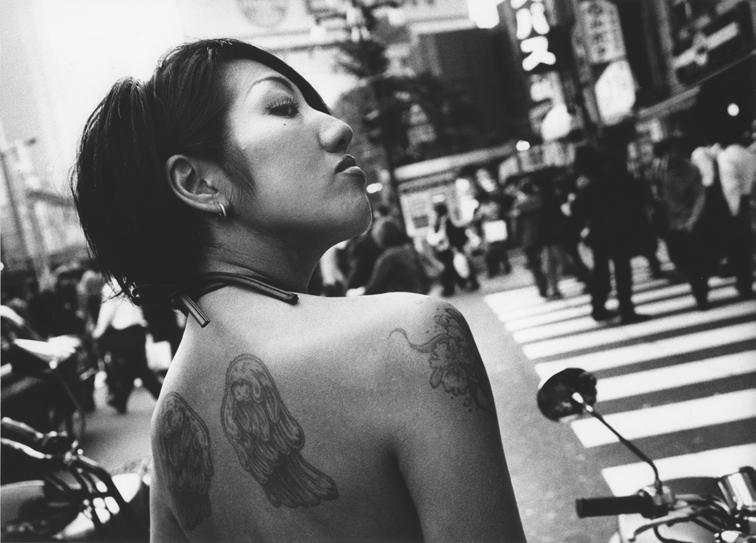

Tokyo has an enormous acuteness. The city comes into existence through so many things, not just people. It is a place that carries and shows the desires of many people, and of particular times. For me, as a photographer, it is something that just needs to be photographed.3

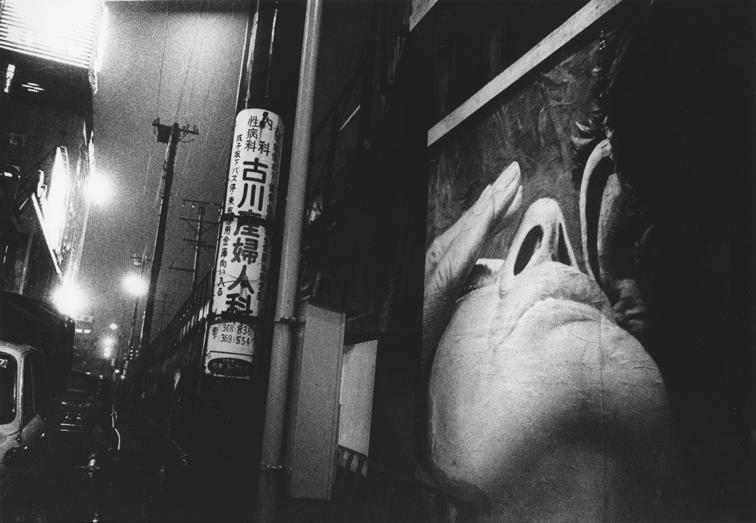

Moriyama Daidō, Shinjuku, 2002

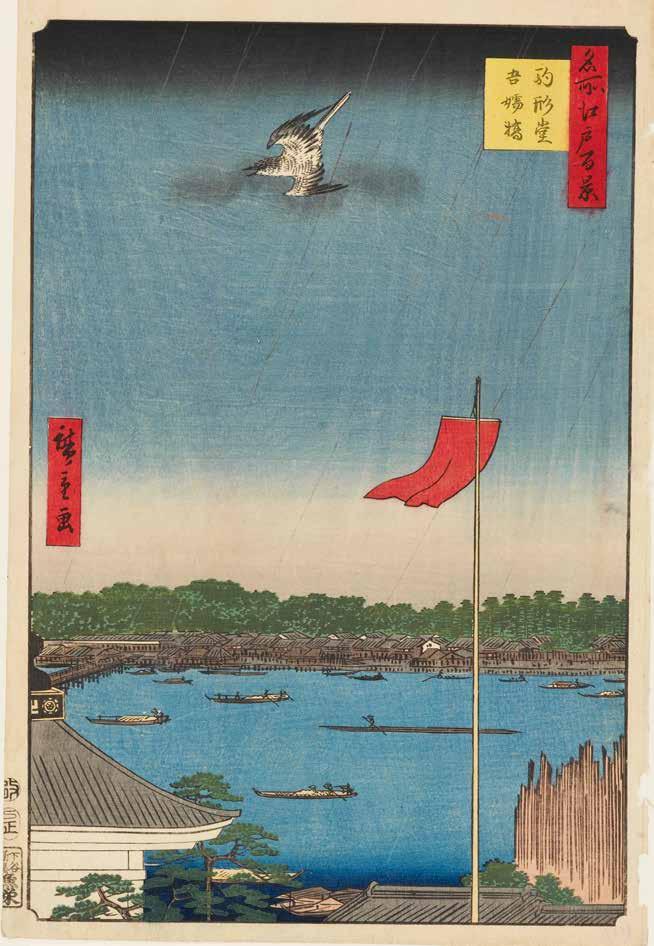

Utagawa Hiroshige, Komagata Hall and Azuma Bridge (Komagata-dō Azumabashi), from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (Meisho Edo hyakkei), 1857

Colour woodblock print, 36.3 x 24.4 cm

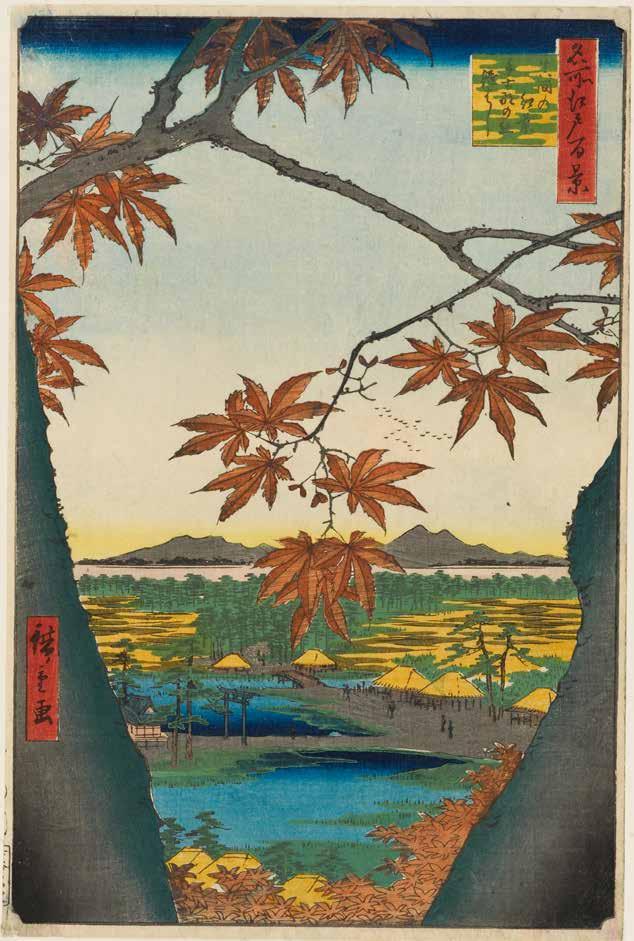

Utagawa Hiroshige, Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Linked Bridge (Mama no momiji Tekona no yashiro Tsugihashi), from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (Meisho Edo hyakkei), 1857

Colour woodblock print, 34.9 x 23.5 cm

Around the same time another artist, Koizumi Kishio (1893–1945), set out to depict the city and its environs in a larger format. His One Hundred Views of Great Tokyo in the Showa Era (Shōwa dai Tōkyō hyakkei zue) is a personal interpretation of Tokyo, created over twelve years from 1928 to 1940 (p.43). In the preface to the series Koizumi states, ‘I would like to become the Hiroshige of the Shōwa era, to achieve my dream of making a life’s work out of one hundred landscape prints featuring Tokyo…’.18 Again, the series depicts the transformation of Tokyo after the earthquake, highlighting industrial sites, public spaces and city lights. However, it also dwells lovingly on familiar and traditional views, with numerous scenes of seasonal festivals and traditional landmarks. The importance of memory and the past in this series is emphasised in the captions that Koizumi wrote to accompany each print, which make frequent reference to significant historical events. Indeed, 34 of his views matched places celebrated in Hiroshige’s classic treatment of Edo in the 1850s.19 There are also a surprising number of suburban and rural views. As part of Tokyo’s ongoing urban redevelopment, in 1932 the five counties surrounding Tokyo were absorbed into the city and Tokyo’s 15 wards became 32. Tokyo was now officially ‘Great Tokyo’, allowing Koizumi to incorporate views that reached far beyond the inner city he had intended to capture at the start of his project.20 Another notable element of Koizumi’s One Hundred Views is his focus on the growing military presence in the city, reflecting Japan’s escalating policy of aggression towards China in this period.21

Some two decades after the earthquake Tokyo was levelled again, this time by the air raids of the Second World War. The portfolio Scenes of Last Tokyo (Tokyo kaiko zue), published in 1945 shortly after the end of the war, shows nostalgic views of fifteen famous places in Tokyo as they were before wartime firebombs destroyed much of the city (p.42). This was a collaboration between nine of the leading Japanese Creative Print artists of the time, including four of the artists who had contributed to the One Hundred Views of New Tokyo. Indeed, seven of the fifteen designs were reworkings of designs that had appeared in the earlier series. Although the main target audience for this portfolio was the American Occupation forces, the Japanese language introduction, thought to have been written by leading printmaker Onchi Kōshirō (1891–1955), expressed deep sadness at the many meisho that had been lost.

However, Tokyo once again rose from the ashes. A major symbol of Tokyo’s post-war renaissance was Tokyo Tower, a broadcasting tower completed in 1958. Constructed partially from scrap metal salvaged at the end of the war, at a height of 333m it was for a long time the tallest structure in Japan (only superseded by the Tokyo Skytree in 2012). It quickly became a prominent landmark in the city and was for Japanese people the leading symbol of Tokyo. The print by Kasamatsu Shirō illustrated on p.40 was published very soon after the tower was completed, while Takahashi Rikio (1917–98)’s print shows the same subject around thirty years later (p.10). The latter work is from the series One Hundred Views of Tokyo: Message to the 21st Century. For this project, undertaken between 1989 and 1999, one hundred leading print artists from the artists’ group the Japan Print

Association (Nihon Hanga Kyōkai) were invited to riff on the classic theme of ‘One Hundred Views of Tokyo’, working across a range of contemporary print media, from woodcut to silk screen. This new set of views was intended to serve as ‘a witness of time to the changing international megalopolis Tokyo’, and ranged from traditional meisho to newly selected ‘alternative views’. Each artist represented a Tokyo of their own perception – figurative or abstract, playful or critical. In a description of his work, Takahashi Rikio writes that he had initially felt uneasy with Tokyo Tower’s close association with the authorities who had taken Japan to war, but on a later visit found himself so ‘enchanted by its iron jungle and the feast of lights’ that he selected it as his motif for the series: ‘I made up my mind to challenge Tokyo Tower’.22

Celebrations of place in Japan have developed over the centuries, from religious through poetic to pictorial representations of various kinds.23 Some ‘famous places’ supplanted others, but more often than not site-specific associations continued to be added over time; new landmarks were simply grafted on to the pre-existing canon of culturally significant places, acknowledging the inevitability of change and allowing a range of creative approaches. This cumulative process is beautifully illustrated in the work of Yamaguchi Akira (b. 1969), whose intricate paintings and prints of Tokyo seemingly combine past, present and future, often incorporating elements of pop culture and science fiction-like fantasy. An artist classically trained in traditional Japanese painting, Yamaguchi draws upon the meisho tradition, whether in prints referencing Hiroshige’s views of Edo (p.41), or in works recalling seventeenth-century screen paintings of famous sites in and around the city, depicted in classic bird’s-eye view and with gold clouds dividing scenes in multiple perspectives and multiple scales (p.233). For Yamaguchi, ‘cities are made up of the accumulated memories of people who have the power to transcend their own time’.24

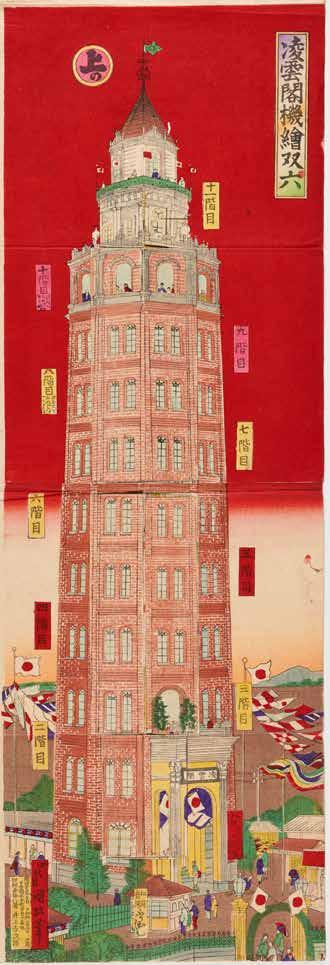

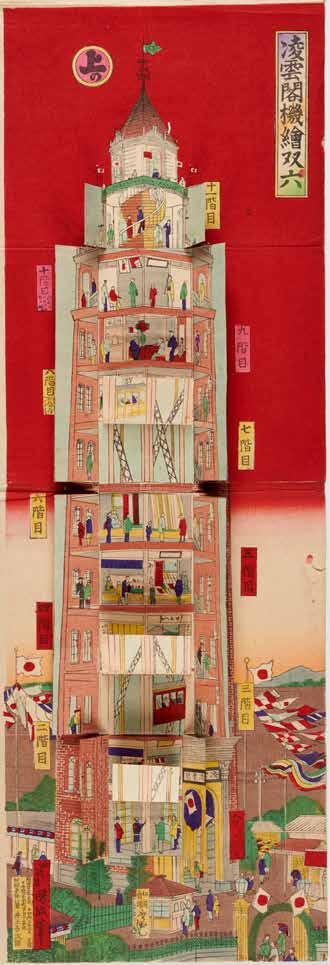

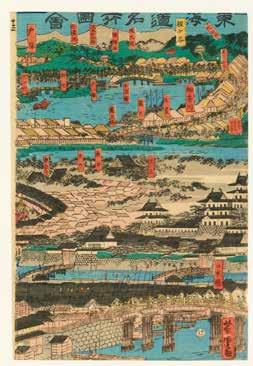

Utagawa Kunimasa IV, Ryōunkaku Tower Game (Ryōunkaku kikai sugoroku), 1890 Colour woodblock print with collage elements, 72.7 x 25 cm

road space are disciplined, with people lined up on the sides.32 The print shows signs of having been hastily made, for example the varying colours of the labels of checkpoints along the Tōkaidō. These glitches point to the shapeshifting configuration of Japan’s landscape during the turbulent years that led up to the emperor’s move to the newly named Tokyo in 1868.

The top-down re-mapping of the city was prominent in the years after the Meiji Restoration, for example in the building of Ginza Bricktown. The city was slowly retro-fitted for the needs of an emerging modern imperial capital. The 1923 earthquake and fire wiped out the vestiges of Edo infrastructure that were then either designated as public parks or reconstructed in more durable brickwork. This process was repeated after the large-scale destruction that occurred during the Second World War. The modern space of Edo became increasingly defined by official structures and the development of urban clusters along major subway lines such as Shinjuku or Ikebukuro lines.

Reactions to this bureaucratisation of Tokyo emerged in the 1960s, for example in the Situationist-inspired urban happenings organised by members of the Hi-Red Center (see contributions by Hayashi Michio and by Lena Fritsch to this book, p.140, pp.144–5, pp.177–9). Such a bottom-up re-appropriation of urban space is also at work in the Diorama Map project run by photographer Nishino Sōhei since 2004 (p.51). His urban portraits resemble bird’s-eye views, but ones comprised of

thousands of ground-level photographs. Nishino sees his work as a record of his interactions with the city, and therefore a way to capture the city’s vital energy.33 The movement of the photographer and the viewer’s gaze configure the metropolis as a non-repeatable event.34

The punctiliousness of Nishino’s maps recalls the hand-drawn and hand-painted works of contemporary map-makers such as Ishihara Tadashi or Muramatsu Akira. Nishino, however, uses the medium of photography almost against its own ends: while usually employed to crop views and places, here it provides the record of a systematic, peripatetic experience of the city. That experience is facilitated by the conspicuous transportation infrastructure – the circular Yamanote Line, for example, is a defining feature of modern Tokyo, and one of the few structures that bind the urban clusters on the circumference of the Imperial Palace grounds.

Nishino’s maps reaffirm a malleability of urban space that has characterised Edo and Tokyo throughout its exceptionally numerous calamities. Just like a kimono, its cut remained largely unaltered while its pattern and decoration constantly changed. In this state of flux, patterns of urban thought, such as a renewed awareness of the role of waterways in structuring the city, periodically re-emerge.35 The study of Tokyo’s cartography can thus combine historical inquiry with reflections on how better to design the city for the future.

Jacob van Meurs, View of Edo, 1670

From John Ogilby’s English version of Arnoldus Montanus, Atlas Japannensis (c.1620–79)

Hand-coloured copperplate engraved book leaf, 28 x 77 cm

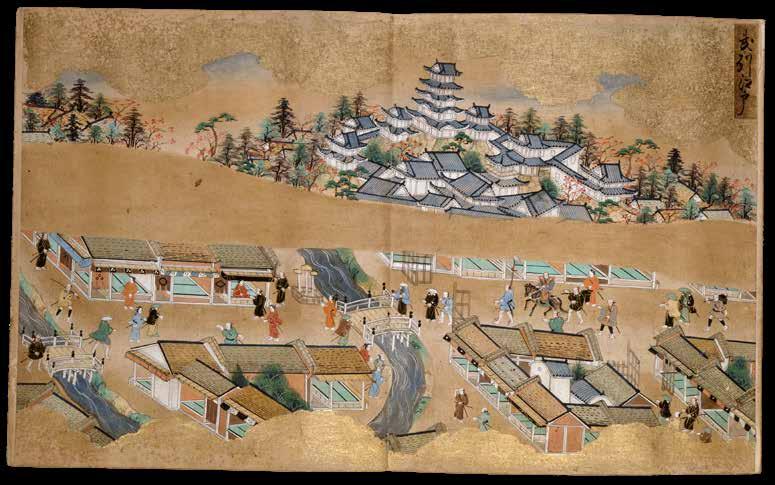

Tosa School, Edo in Musashi Province (Bushū Edo), from a set of six albums, Record of Famous Sights of the Tōkaidō Road (Tōkaidō meishoki), late seventeenth century Ink, colours and gold on paper, 17.5 x 14.5 cm

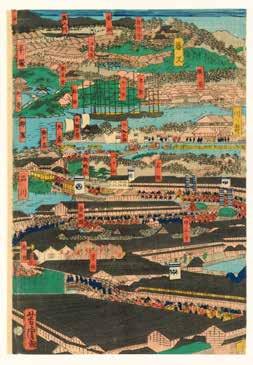

Utagawa Yoshitora, Famous Places on the Tōkaidō: Shogun’s Procession to Kyoto to Meet the Emperor (Tōkaidō meisho zue), three prints from a set of twelve, 1864 Colour woodblock print, each print 38 x 25.6 cm

EDO AND THE ARTS OF WAR AND PEACE

Ceremonial suit of armour, made for a member of the Oda family, eighteenth century Steel, iron, gilt iron, lacquer, deer skin, silk, 160 x 140 x 56 cm (max.)

After over a century of fierce civil wars between rival samurai lords, Japan was unified in the early seventeenth century under the Tokugawa family of shoguns, or military rulers. For the next two and a half centuries the country was at peace, with the Tokugawa shoguns ruling from their headquarters in Edo via a network of semi-autonomous provincial warrior lords, or daimyō, served by lower-ranking samurai. As a clever way of limiting the possibility of daimyō insurrection, the shoguns introduced the ‘alternate attendance’ system (sankin kōtai) (see p.25). This system played a key role in how the city of Edo developed. With more than 250 daimyō retinues coming and going, and hundreds of daimyō mansions located near Edo Castle, a flourishing service and retail industry developed to cater to the needs of the samurai. A huge range of products and customs was imported from all over Japan, and Edo culture then circulated back to the provinces. The city quickly became a cosmopolitan hub of economic and cultural life in Japan, as well as its political heart.

From as early as the twelfth century, military governments in Japan had recognised the importance of developing their administrative and cultural talents alongside their warrior skills in order to rule the country effectively and to demonstrate their own legitimacy. The Tokugawa shoguns continued to emphasise the martial ideal for the whole samurai class, formulating a code of conduct that became known as bushidō (the ‘way of the warrior’). This was a set of rules and principles based on Confucian teachings; it placed a strong emphasis on loyalty and honour as the essence of a samurai’s existence.

However, the Tokugawa also understood the need to tame the warriors and to channel their military energies towards the ‘arts of peace’. The Regulations for Military Houses (Buke shohatto), a collection of edicts issued in 1615 regulating the duties and behaviour of the warrior class, opened with the instruction that the arts of peace (bun) and the arts of war (bu) should both be pursued ‘single-mindedly’. As both warriors and leaders of society, samurai were required – even in peacetime – to train in military arts such as archery, falconry and swordsmanship. Yet at the same time they were expected to devote time to the administration of their provinces, Confucian studies and the cultivation of traditional arts, including nō theatre, the tea ceremony, poetry, painting and calligraphy.38

Although there was no opportunity to appear on the battlefield in peacetime, arms and armour were still needed as symbols of personal status. They were displayed on ceremonial occasions, during military drills (such as the dog-chasing game depicted in the folding screen on pp.54–5) and for the compulsory processions between a daimyō’s regional domain and Edo. These processions, part of the sankin kōtai system, often comprised hundreds if not thousands of retainers and family members, providing an opportunity for daimyō to demonstrate their power and taste

As memories of war receded armour became more decorative, with stencilled leathers, ornate gilded plaques and rich brocades. Inspiration was often taken from the armour of earlier

periods that recalled the glories of the samurai’s warrior past. The suit of eighteenth-century armour illustrated opposite belonged to Oda Nobuhisa, Lord of Ōmi province in central Japan. It incorporates a wide-spreading neck guard and large shoulder guards in a style that had been popular centuries earlier but had been abandoned as too cumbersome during the civil wars of the sixteenth century. The entire cuirass is wrapped with a sheet of printed deerskin. Again this was a feature that had been popular many years earlier as a method of keeping the braided silk lacing dry and protecting it from vermin, but here used solely for decorative effect.

Swords too changed in style over the course of the Edo period as they became more symbolic than functional. The samurai sword was not just a superbly crafted weapon to be appreciated for its cutting efficiency and for the intrinsic beauty of its metallurgical qualities; it was also a symbol of power, famously described by the first Tokugawa shogun, Ieyasu, as the ‘soul of the samurai’. During this period only samurai were permitted to carry a pair of swords. Edo, with its large population of samurai, became a centre of sword production, with many daimyō bringing top swordsmiths from their own domains.

The two blades illustrated on p.56 both date to the late seventeenth century. Above is a katana – the long sword that only samurai were permitted to carry during this period, usually worn as part of a pair with a short sword. This blade, attributed to the renowned seventeenth-century Edo swordsmith Ishidō Korekazu, displays a beautiful hamon – the distinctive wavy pattern created during the tempering process. As with armour, some swordsmiths looked back to earlier models; the shape of this blade, slightly flattened at the tip, suggests that it was made to simulate work of the fourteenth-century Ichimonji school.

The blade below is a short dagger or tantō. It was forged in Edo by smiths from the Yasutsugu family, who worked as official swordsmiths to the Tokugawa shoguns. Originally from Mino province, also in central Japan, the first-generation swordsmith Yasutsugu earned the patronage of Tokugawa Ieyasu and was called to Edo at the beginning of the seventeenth century. He was awarded the privilege of using the character ‘Yasu’, from Tokugawa Ieyasu’s own name, and the right to carve the Tokugawa family crest on his blades. This is a rare example of a blade made by the third-generation Yasutsugu (1630–69) and signed at a later date by the fourth generation. The blade has been decorated on each side with a carved design (horimono) by the Kinai family, who specialised in such engravings: one side bears a Buddhist banner, the other a dragon with an auspicious Buddhist Sanskrit inscription seeking strength from the wrathful deity Fudō Myōō.

The third sword is a tachi-type sword, mounted in the formal style known as itomaki (cord-wrapped) tachi (p.57) The matching fittings are decorated with the Tokugawa crest. The tachi was worn hung from the belt; it was originally designed for use on horseback, but during the Edo period was worn for ceremonies at the shogun’s court or presented as a gift to other samurai lords. While the quality of blades gradually declined

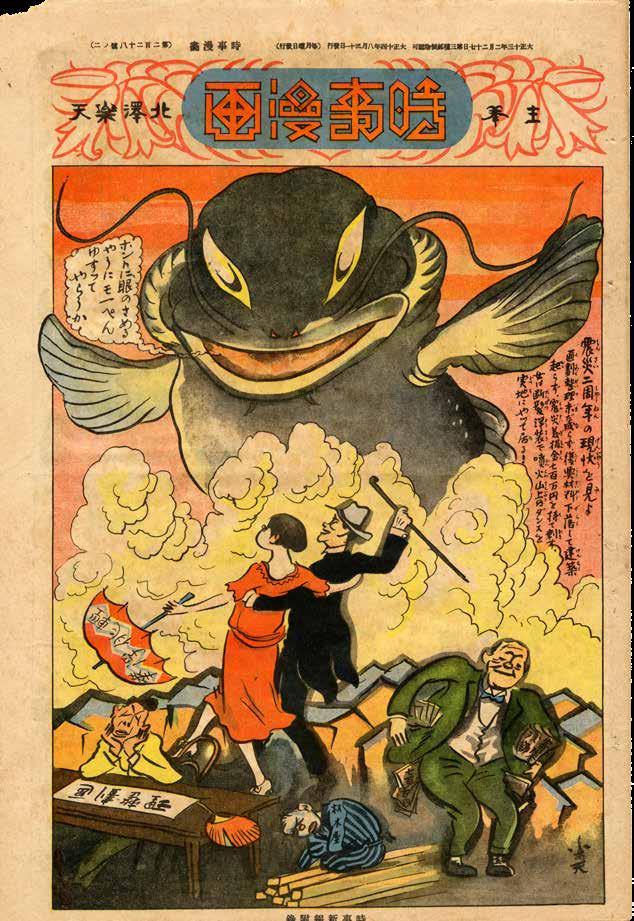

Kitazawa Rakuten, Earthquake Edition (Jishingō), cover of Jiji Manga, no.132, 7 October 1923

Colour lithograph, 40.6 x 26.8 cm

Kitazawa Rakuten, Behold the Status Quo of the Second Anniversary of the Earthquake (Shinsai nishūnen no genjō o miyō), cover of Jiji Manga no.228, 31 August 1925 Colour lithograph, 40.6 x 26.8 cm

Toyohara Kunichika, 6 a.m. (Gozen rokuji), from the series Scenes of the twenty-four hours, a pictorial trope (Mitate chūya nijūyoji no uchi), c.1890

Colour woodblock print, 39 x 27 cm

Toyohara Kunichika, Photography (Shashin), from the series A Mirror of Civilised Manners and Customs (Kaika ninjō kagami), 1878

Colour woodblock print, 37.5 x 25.4 cm

designs are most likely not based on a scene from any particular performance.111 The prints in this series are often a topic of discussion, due in part to their openly erotic overtones. In 1935 the Tokyo police confiscated the blocks of a print from the series. According to the block cutter who worked on the series, two woodblocks were destroyed.112

The moga caused commotion in various circles, mainly because she was an independent woman who sought to transform herself and to contribute to society. Due to the rapid modernisation of Japan at the beginning of the twentieth century, and with the help of mass-market women’s magazines (p.109), modern young women were able to find work outside the home and look for personal fulfilment.113 With the arrival of the first department stores, jobs such as ‘shop girl’, ‘mannequin girl’ or ‘elevator girl’ became available. In addition, the rise of café culture brought the occupation of café waitress, and the

often-discussed ‘services’ that she offered to her clientele.114 However, these were also spaces where men and women could freely socialise together (p.113). With the job market opening up to a new workforce, women could gain access to a disposable income. In 1904 the well-known shop Mitsukoshi declared itself a department store; modelled after those in America and Britain, it was the first of its kind in Japan. While Mitsukoshi employed moga, they were also targeting modern young women to come to the store. Posters were specifically designed to attract new customers to buy the latest and trendiest items available (p.98, p.100).115 The store invested in a nationwide marketing campaign to advertise it as one of the must-sees when visiting the capital of Tokyo.116

However, Mitsukoshi was not only a store. It was also a social intersection, where lectures, concerts, exhibitions on contemporary Western art or Japanese arts and crafts were

Kawakami Sumio, Night of Ginza (Yoru no Ginza), from the series One Hundred Views of New Tokyo (Shin Tōkyō hyakkei), 1929 Colour woodblock print, 19 x 26 cm

held.117 A visit to the department store or the trendy shopping district of Ginza was a very fashionable excursion. Strolling along the Ginza, where numerous shops, trendy cafés and restaurants had formed, became an activity on its own: ginbura, a composition of Ginza and burabura, or ‘aimlessly wandering’ (above left). Young people gathered in the area and so this was the place to see what was trendy and to be seen wearing the most recent fashions.

In 1927, when moga were still a fairly recent phenomenon, the painter Kishida Ryūsei (1891–1929) described his experience of encountering these women on the Ginza:

When you step into the Ginza, it really is modern. A beautiful, short-haired missy skims her way through like a swallow, just before me, as I absentmindedly shop for drawing materials. She walks fast as if she were different

to the girls of only a decade ago. Another group of three beauties come from the opposite direction. There really are a lot of women out these days. In former times one rarely met a lady when one went out, but today they are many. None of them seem to have anything particular to do, yet they all rush by.118

Other popular forms of modern entertainment were Western films shown in cinemas and dance halls, along with contemporary plays at theatres and shows by Western performers at concert venues (above). These Western-inspired varieties of amusement formed a new playground for fashionable youth and were key to modern life in the capital. Many of these places were subjects of the print series One Hundred Views of New Tokyo, created by a group of artists dedicated to depicting, and as a result documenting in art, the modernities of life in Tokyo during the 1920s and 1930s (see also pp.38–9).

Onchi Kōshirō, Hibiya Concert Hall (Hibiya ongaku-dō), from the series 100 Views of New Tokyo (Shin Tōkyō hyakkei), 1930

Colour woodblock print, 20.5 x 26.5 cm

Naitō Masatoshi, Snakecharmer, Asakusa, 1970 from Tokyo: A Vision of its Other Side series

Ishiuchi Miyako, Apartment #50, 1977–8

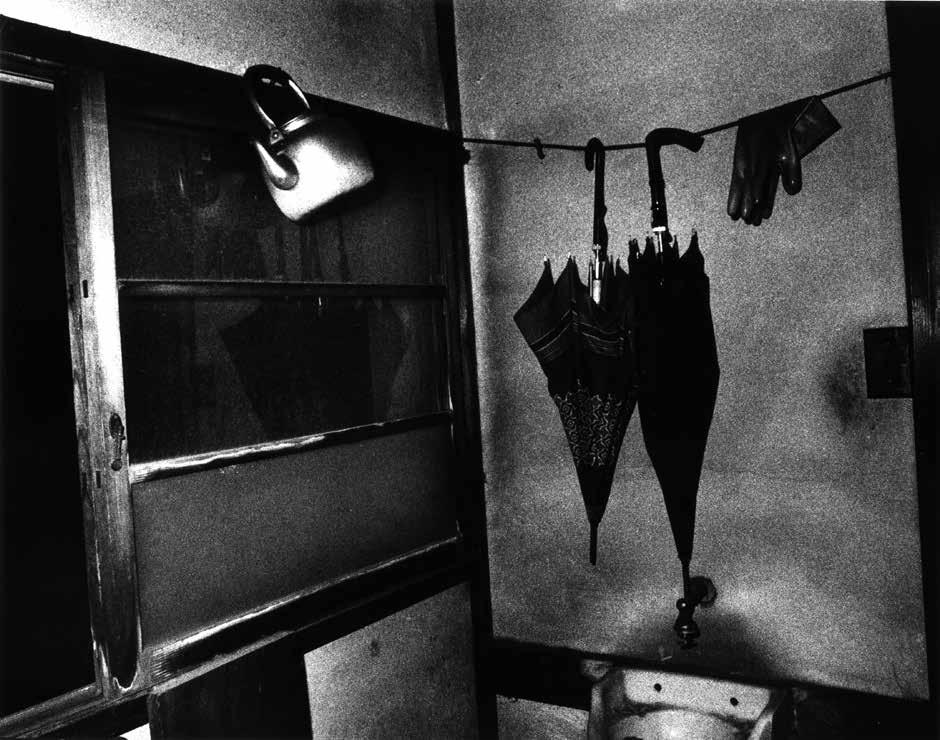

Moriyama Daidō, from Hunter series, 1972

Ninagawa Mika, all from Utsurundesu series, since 2018