LENA FRITSCH

Now internationally celebrated, the British band Radiohead was originally formed in Abingdon, Oxfordshire in the mid-1980s. Comprising Thom Yorke, brothers Jonny and Colin Greenwood, Ed O’Brien, and Philip Selway, the band members were all pupils of Abingdon School, an independent day and boarding school for boys. After signing to EMI in 1991, they released their debut album, Pablo Honey, two years later. Following the great success of their first single, Creep, their international popularity and critical standing rose rapidly. Not your average band, Radiohead has presented elaborate musical structures and created unusual sound worlds, linking experimental rock music with electronica, orchestral instrumentation, and a wide array of other musical influences ranging from jazz to techno, while using a rather abstract harmonic language. The lyrics are poetic, political, and powerful, performed by Yorke in his distinctive voice. The records differ to each other in style and mirror the dedication of the band to continuously breaking musical barriers and creating new sounds. To date, Radiohead have sold more than 30 million records worldwide and Creep has had over 1.7 billion streams on Spotify. Since 2014, their award-winning album, OK Computer (1997), has been preserved in the US Library of Congress. In 2019, Radiohead were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

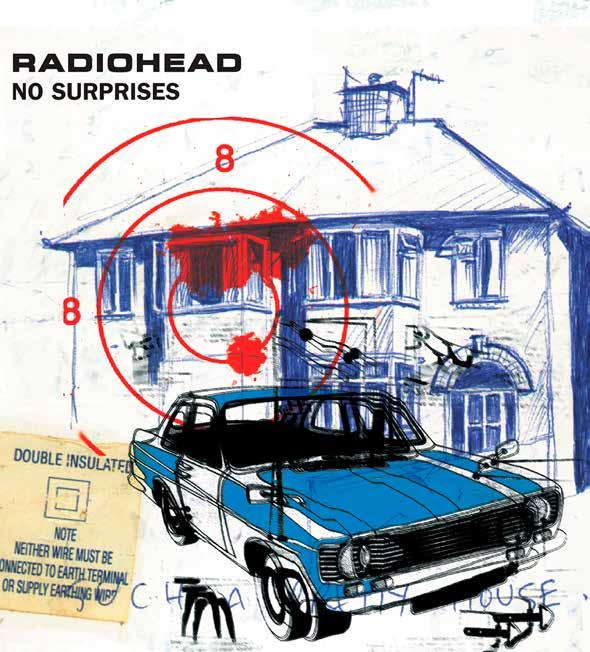

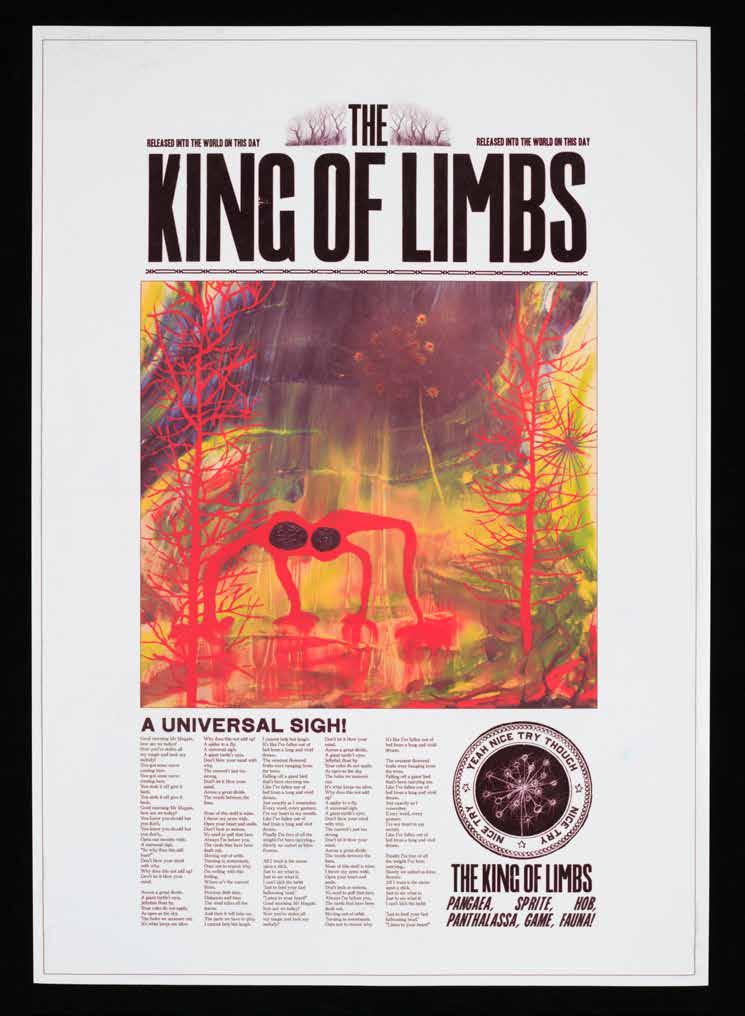

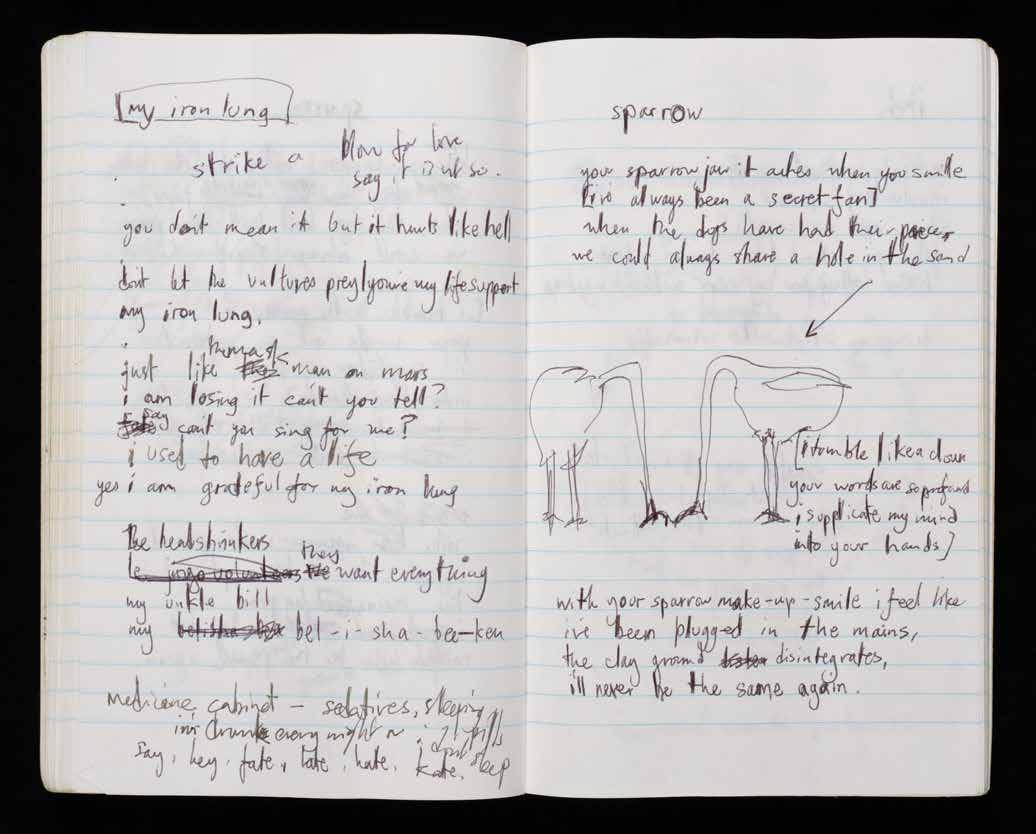

Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke (b.1968) and artist and writer Stanley Donwood (b.1968) first met at the University of Exeter while studying for a joint honours degree in English literature and fine art. Yorke remembers seeing Donwood for the first time at college in a ‘tweed cap and green tweed suit’, reading a book and looking ‘like he was there by mistake’. Meanwhile, Yorke himself was a ‘shaven-headed guitar-playing pretend DJ type who was going to do music’.1 They became friends and first joined forces in 1994 when designing the cover of Radiohead’s single My Iron Lung and related second album, The Bends. After filming a CPR mannequin in the basement of John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, Donwood and Yorke photographed the film visuals on a TV screen, which resulted in striking, pixelated images. They have now collaborated for over three decades, exchanging ideas and bouncing images and texts off each other in various ways, be this by faxing each other letters, jointly manipulating images on a computer, or by sitting at different ends of a desk and erasing each other’s drawings. Their artistic partnership has resulted in an extensive archive of visual material linked to Radiohead’s CD and LP covers, booklets, posters, merchandising products, and internet projects. Their work has also been used on record covers for Yorke’s solo projects, and for his recently founded band The Smile. Sometimes figurative, sometimes abstract, and using a wide range of artistic materials, their works have linked music and text with visual imagery in experimental ways. Together, Donwood and Yorke have pushed and led ad absurdum the boundaries between record covers, artworks, and music marketing in a distinctive way.

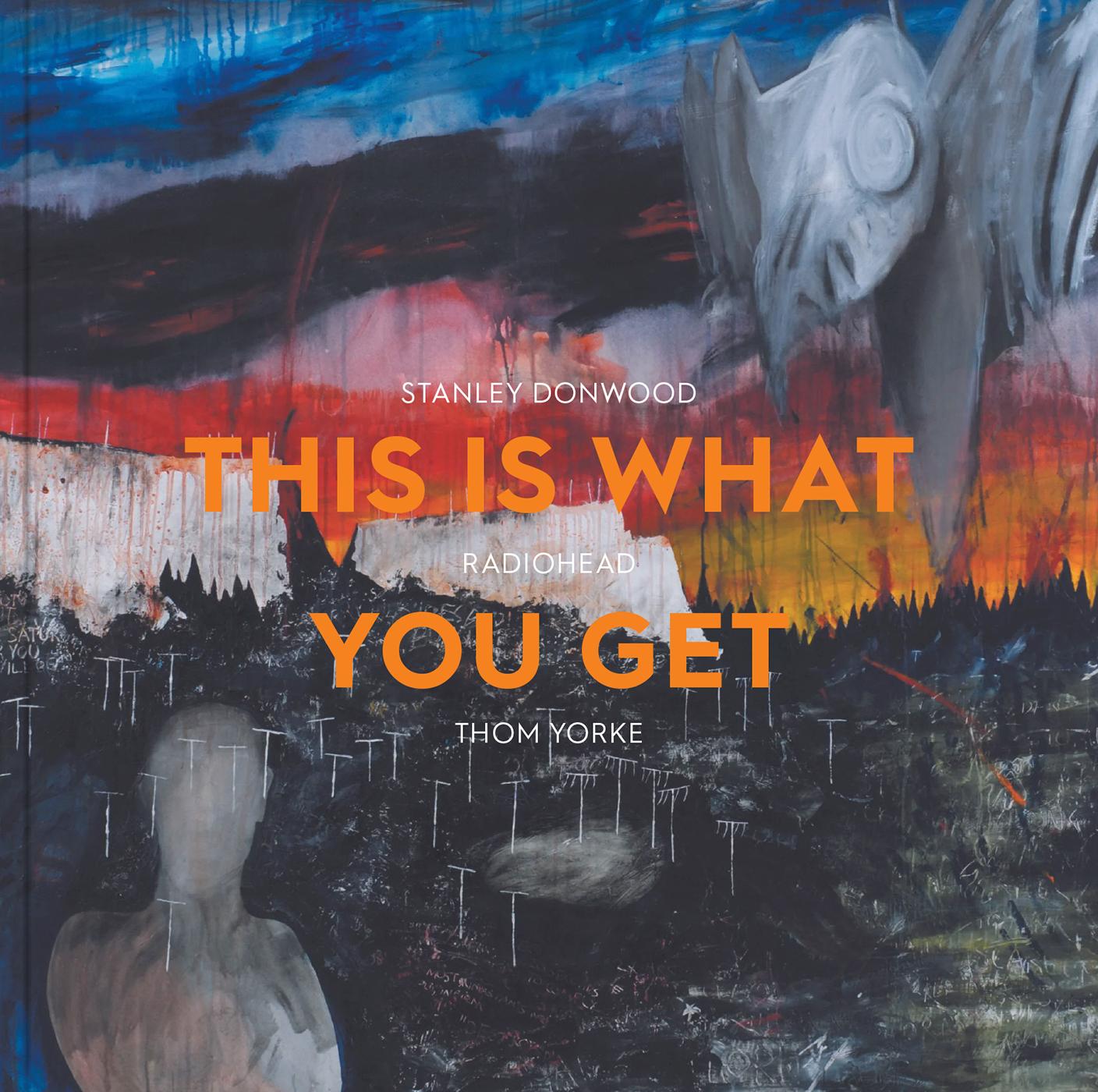

This book features a carefully curated selection of the visual works of art by Donwood and Yorke, made over the last 30 years to accompany albums by Radiohead, Yorke, and The Smile. Organised chronologically, it showcases the great variety of their collaborative work, ranging from well-known digital compositions to tempera paintings, and from iconic etchings to unpublished drawings from their sketchbooks. The book title, This Is What You Get, a line taken from Radiohead’s well-known song Karma Police (1997), represents their artistic approach: direct, honest, poetic, dark, and sometimes comedic. The artworks are complemented by exclusive interviews with Donwood and Yorke, representing the artists’ own words, and reflecting their unique, playful approach to working together creatively. Four essays explore their works from diverse new perspectives and contextualise them in complementary ways. Director of Tate Britain, Alex Farquharson, writes from a personal angle about his time with the artists at the University of Exeter in the 1980s, and explores their unique approach to creating visual art in dialogue with music; independent curator James Putnam introduces the art of record covers and related collaborations between artists and musicians more broadly; British Museum curator and drawings expert Jennifer Ramkalawon views the sketchbooks made by Donwood and Yorke in the context of art history; freelance writer

RADIOHEAD, THE BENDS, 1995

Lena Fritsch Could you tell me how that image on the cover of The Bends (p.xx) came about? It’s quite an experimental image, considering the different artistic media that are involved.

Stanley Donwood At the time, all of the TVs were analogue. So, when you got close to them, their display was really interesting, like a pre-pixel world. We had a video camera and went out filming material, all sorts of things, it didn’t really matter what it was. We then played it back on Thom’s TV and photographed the TV screen with a film camera.

Thom Yorke Because of the problems with resolution, the first thing we found ourselves doing was starting with a very small, shitty digital image and blowing it up. And the blowing it up would pixelate it …

SD Even more than it already was.

TY But in a way that we liked. I was definitely obsessed with filming the TV. There was a guy at our art school, who was in the year above. We had a video department at the art school. He’d shot this thing and reshot it off the screen, and then he reshot it again, and again, maybe ten or fifteen times, and it had become this mush. I thought, ‘That’s a painting!’ I don’t care what the original thing was. So, that had a big effect on me, and I was really into this pixelation-crunching-animage-up thing. But we had literally just started and didn’t really know ...

SD We didn’t know how to use Photoshop.

TY It was as much just about finding technology and figuring out how to do really basic stuff as anything.

LF How did the idea come about to then go to a hospital?

SD God knows.

TY That was probably your fault.

SD It was a literal thing, because the song was called My Iron Lung, and I was like, ‘Let’s go and find an actual iron lung and film it’, because I didn’t know what they looked like. Somehow, we got in. It was something to do with Colin [Greenwood], wasn’t it?

TY Maybe, yes, Colin knew someone. Anyway, we weren’t supposed to. We managed to get into the basement of the John Radcliffe Hospital [in Oxford].

SD Yes. Very, very bad to go into a hospital with a video camera.

TY We shouldn’t have. I don’t know how we got in. We weren’t supposed to be there.

SD So, they had an iron lung, and we went to this horrible storage area.

TY Scary.

SD Yes, like something from a low-budget horror film, and in there was an iron lung which, in fact, is very boring.

TY Yes.

SD It’s just a metal box.

TY But next to it ...

SD Somewhere else there was a resuscitation dummy.

TY There were a few of them, actually. The resuscitation dummy was literally lying there.

SD It was, yes. And it had these metal nipples that you put the defibrillator on, and you go ‘duh-duh’ to practise, so you don’t make someone worse when they’re having a heart attack or something. I don’t know.

TY Then we stretched the image, distorted it a bit to exaggerate the expression.

SD Not very much, though, because I think we had a deadline of the next day. A deadline from the record company.

LF So, basically, when you went out to take the video, then photographed it and put it on the computer, you already had in mind that this was going to be the LP and CD cover image?

SD No, we didn’t know it was going to be the cover until it was there, and it had Radiohead written across it. We just had a deadline for the cover. We would have probably used something else if it hadn’t looked good. We’d only just figured out how to use Photoshop. And also, fundamentally, it turned out we didn’t know about the difference between RGB and CMYK.

TY Hence, all the blues and reds inside are wrong. [laughs]

SD Yes, because they all look great on the screen, but when you print in onto actual records, then it was like, ‘What’s that muddy mauve colour?’ ‘That’s your blue.’ So, good job there’s not too much blue on the front cover. [laughs]

TY Good job the record sold all right. It looked like we meant it. [laughs]

SD Yes.

TY There was a lot of fighting technology and not knowing what we were doing, which was kind of fun.