FOREWORD

INTRODUCTION

ESSENCE 21

PROVIDENCE

BEYOND BELIEF

LORE OF THE JUNGLE

HANDMADE 34

STRANGE WOOD

MINISTRY OF WOOD CARVING

SIZE MATTERS

LOCAL DÉCOR

LABOUR OF LOVE

HEAD ABOVE WATER

FORTUNE’S WHEEL

ANCIENT TRADE 59

VITAL INGREDIENT

REGAL WAYS

MIND’S EYE

GOLDEN VESSELS

COLONIAL PROJECTS 74

ESSENTIAL HARDWARE

FORTY-SIX GUNS

GOING THE DISTANCE BACK ON TRACK

OLD IS GOLD

AGENTS OF THE CROWN TAINTED LOVE

DANISH REALM FOREST LIFE

TWISTED FORTUNE

LAW OF THE LAND PROVENANCE

DYNASTY 112

FAMILY TREE THE MECHANIC FINAL STRAW

EXTRACTION 125

NATURAL CALLING MOUTH AND KNEES

RISKY BUSINESS ALL EARS

CHAINSAW FAMILY TREE 136

FEWER TREES

MOVING ON VALID CONCERNS

AFTER THE GOLDRUSH

ORDER OF THE DAY 145

WE COULD FOLLOW ESPECIALLY FAIR STEALTH POETIC INJUSTICE WITH THE FLOW FEEDING FRENZY THE FLOOD GREEN ACTIVITIES TEACHER FRIEND

DESIRE 164 RUMBLE IN THE JUNGLE NO OBJECT NEXT GENERATION

END OF WILDERNESS 181

FOREST CHRONICLE WOOD FOR THE TREES

END OF WILDERNESS

GOLDEN BREED

ADAPTIVE EVOLUTION

FOREST WATCH

ONE WAY TICKET

PLANTING OUT

THE PEOPLE’S TREE

MORE THE MERRIER

GROWN ON TREES

DIMINISHING RETURN

THINK LOCAL, ACT GLOBAL EARLY HARVEST

NEW ECOLOGY 216

SHOW ME THE MONEY EXTINCT IN THE WILD

A BETTER TREE

NEW ECOLOGY

TRANSITION PERIOD

PART OF THE PROBLEM

SCARCITY 233

TWENTY-TWENTY VISION WANTS AND NEEDS

PRICE IS RIGHT

PARADISE LOST

NEW ID

NEEDS AND WANTS

EPILOGUE 247

STARTING AGAIN

GLOSSARY 248 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 252

Teak is an especially rich topic for a book about a part of nature that has been radically commoditised and thus turned into a dynamic aspect of human affairs. The book you are about to experience is a remarkable social history of a commodity and the first major work to chart the journey of teak from the tropical forests of South and Southeast Asia to much of the rest of the world.

My parents migrated to Mumbai in the early twentieth century from Tamil South India which had deep ties to the world of teak in Burma through the Nattukottai Chettiars, whose magnificent homes in Tamil Nadu were products of wealth gained in their commerce with Southeast Asia. Later, in 1938-39, my father was a Special Correspondent for Reuters in Rangoon (Yangon), where one of my brothers was born. Burma became integrated into the Indic world, partly due to the British empire, but also commerce, teak and migration between South India and Southeast Asia. Today’s Myanmar became a late addition to the long history of teak extraction and shipbuilding in India. For those of us who grew up soon after India achieved independence in 1947, teak was a luxury wood more connected to the home furnishings of wealthy families than to shipbuilding or commerce.

Reading this extraordinary book and gazing at its exceptional photographs, I think of how teak fits into the general approach I took to the social life of things and several key themes return to me.

Through the story of teak, we are forced to acknowledge that the contrasts between oceanic and land-based processes are highly artificial products of our disciplinary habits and prejudices. Teak is a quintessential forest product, and nothing is more part of the land masses of the earth than teak. But as soon as teak becomes an extractable and marketable commodity, it takes on a maritime life through shipbuilding, commerce and conquest. Land and sea are inseparable in the social life of teak. Ships themselves are living reminders of this connection.

Teak also reminds us of the essential links between things, animals and environments in human life. For a long time, elephants were key intermediaries. Notably in Burma, the social lives of teak forests, elephants, their trainers and timber owners are intimately intertwined. As photographs in this book reveal, elephants are themselves commoditised in the process of commoditising teak.

Lastly, Virginia Henderson and Tim Webster show some of the qualities of teak in their own endeavours: endurance, strength, mobility and shape-shifting. Their book is a beautiful tribute to the idea that things have social lives, as it shows that the social lives of human seekers of knowledge are moving things in themselves.

Arjun Appadurai Berlin, 2023Constructed entirely of teak, the nineteenth-century Innwa Bagayar monastery in Amarapura, Myanmar, features two hundred and sixtyseven posts fashioned from old-growth trunks.

PROVIDENCE

BEYOND BELIEF

LORE OF THE JUNGLE

We are Asari, which is a caste. I’m a carpenter by birth but the only uru builder in my family.

These boats are Arabic or Persian designs.

Carpentry of urus has taken me to various places in the Gulf. I first went to Qatar in 1986 to repair urus then went to Dubai to finish a vessel. I was the master carpenter of an uru weighing fifteen hundred tons, two hundred feet long with a hundredand-forty-five-foot keel.

These boatbuilding skills aren’t formally written down or necessarily passed from father to son. The master carpenter works with many apprentices. He identifies a couple with real talent and begins mentoring them, giving specific tasks such as laying the keel, making the template and drawing the plumb line. Proportion and technique come into their heads. Acquiring those skills happens on the job, hands on.

Normally when uru building starts we are six to ten men, but at its peak, there are about thirty carpenters before the number drops again. We’ve built eight urus in the five or six years I’ve been at this antique shipyard.

Long logs are still cut using a traditional pit saw and curved pieces such as the frames are always cut by hand. We cut smaller logs using an electric saw. These days we don’t go into the forest looking for crooked timber but take a baulk with huge width and cut out the shape, dipping a rope in charcoal to mark the cutting lines.

I’m Khalasi, a Mappila Muslim. We work on all things to do with moving heavy weights, including launching urus, although now our work is rare. We do a Hindu puja ceremony at the beginning of each job then seek God’s help as we roll the winder and pull the ropes. Our songs are ancient, a mix of Arabic, Malayalam, Hindi and Urdu. Singing coordinates the labour, bringing the mind, eye, brain and hand to one point.

To build their ships, the East India Company selected places with the right kind of teak. Trees in the northern part of the Western Ghats grow crooked so the bent structures for boats came from Saurashtra while the long timbers used for the keels and planks came from the south here in Kerala.

The Indian teak ships created a row in the UK because they lasted some four times longer than ships built of English oak. But as soon as the Suez Canal opened, hulls and basic structures were no longer made of wood. So why then did the British plant teak saplings all over India? For the railways. The Wadias sent a family member to Britain to gain an understanding of the new shipbuilding technology, but this gentleman found the textile mills in Manchester more interesting. Probably thanks to that the British lost interest in making their ships in India.

Teak originally was a building material.

Traditional Indian houses have thatched roofs on a set of columns, rafters, runners and beams, intricately built. No nails are used but these wooden houses hold together well. The weather in the western part of India is very monsoon dependent. There’s a lot of water. It’s quite like the sea. Since Kerala is very humid, it also has large numbers of insects. Teak can withstand all this.

Teak is not the only timber used for house building but a grand timber used for the houses of wealthy people. If you proclaim that you have built a house of teak, you are considered rich. Teak has status.

In India, all the Hindu temples and these days Christian churches have a flagpole often covered with brass or gold. It has to dominate the rest of the structure so the diameter is large, a single straight log tall enough to tower over everything else. You might find a local politician’s flagpole is bamboo, but God must be given the royal tree.

There are places in central Kerala where the owner of a teak estate identifies trees that will grow the tallest and dedicates the largest one to their temple. When the tree is needed it is cut down, taken away and put into an oil bath to season it.

Around Calicut, the mosques resemble temples. The Thekkepuram mosques built in the fifteenth century used a lot of teak and are very ornately carved. Most were funded by shipowners.

Kerala’s boats, the urus, originally belonged to Arab traders. When they sailed here and needed repairs, they hired traditional local craftsmen engaged in temple construction. Those carpenters learnt about uru design and orally passed on those trade secrets from generation to generation. Beypore uru makers are true artisans. . We have at least a dozen of them here capable of conceiving and building large vessels without any plans on paper.

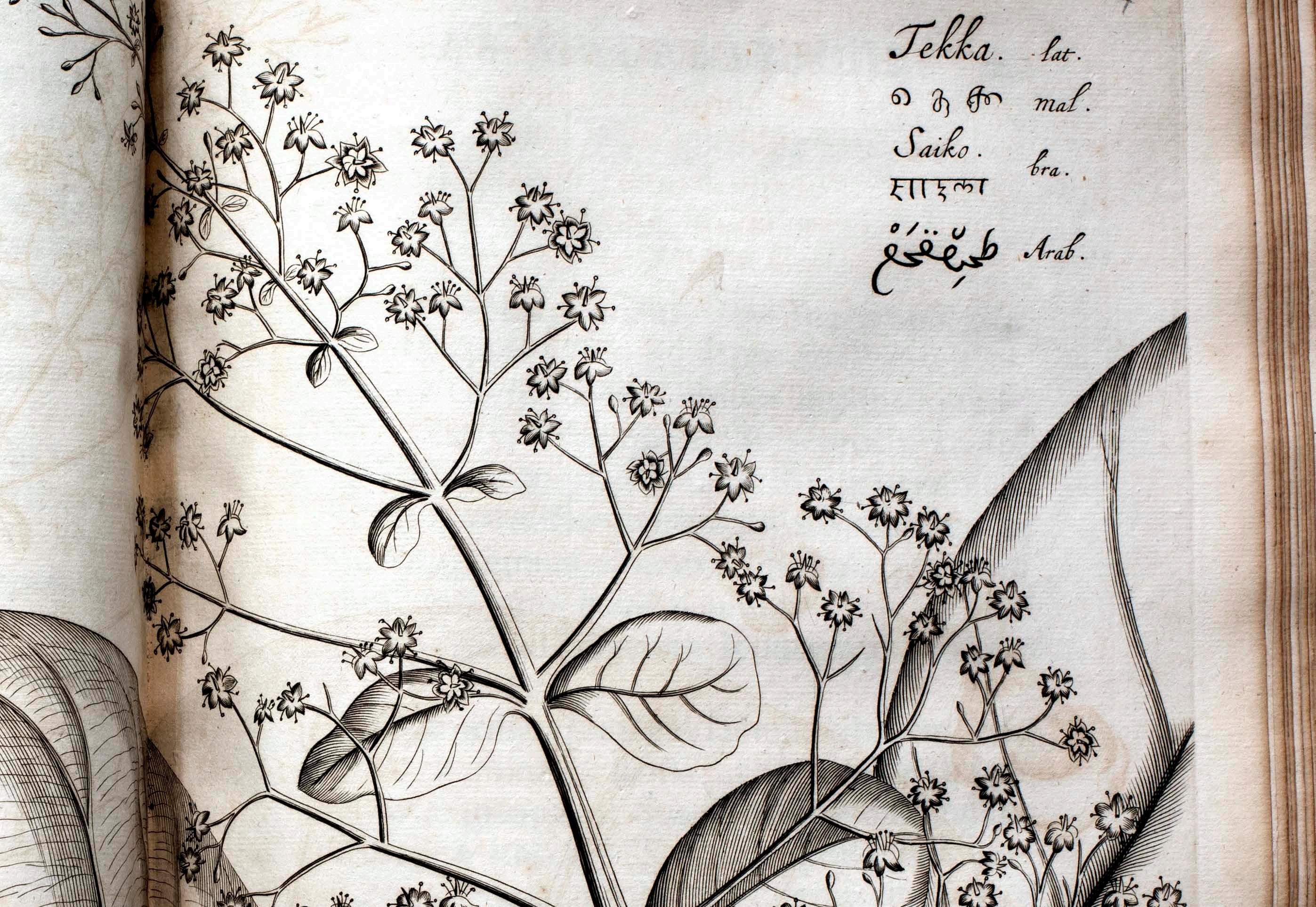

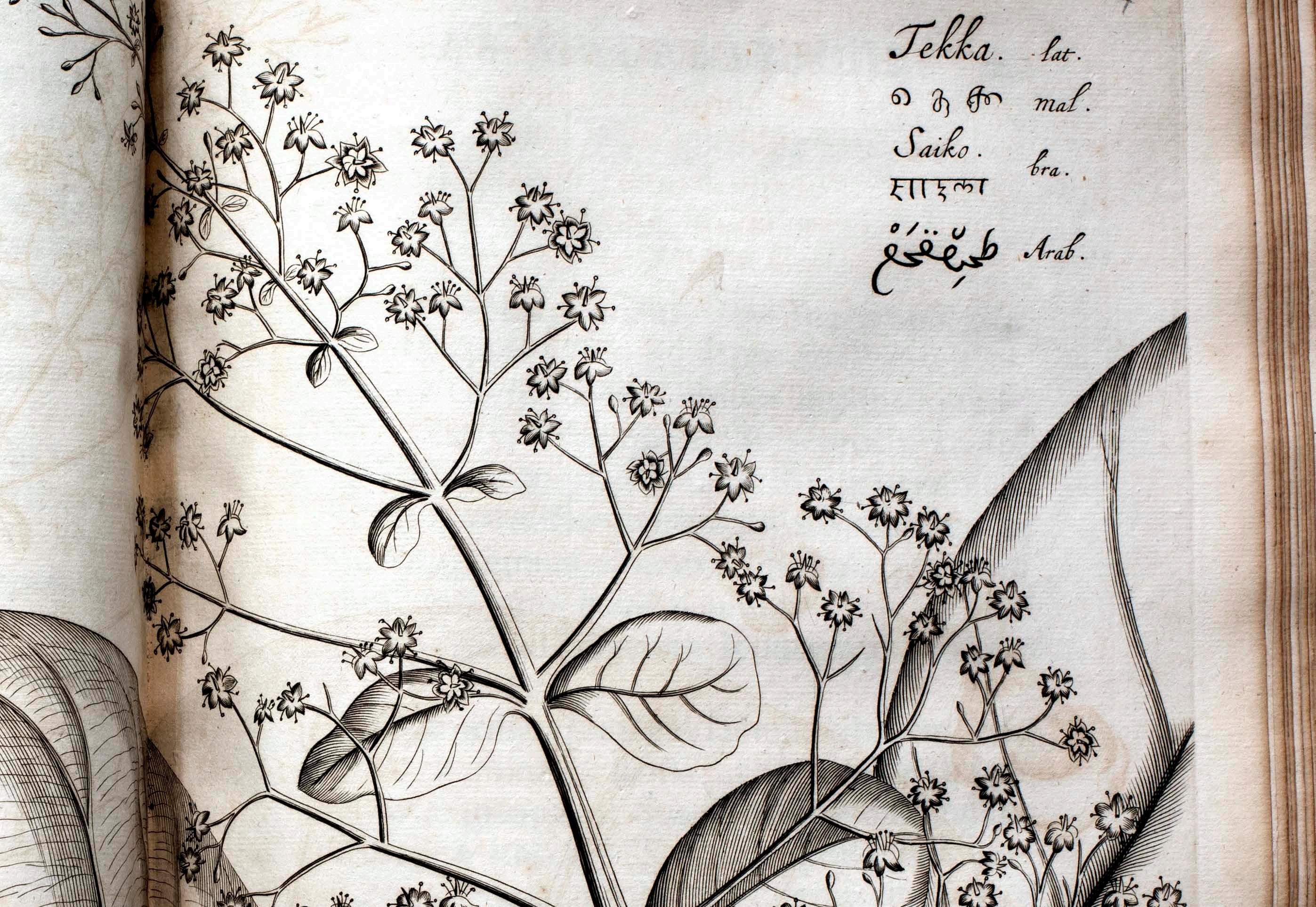

There are records connecting teak from India to ancient civilisations, say four or five thousand years ago.

The Old Testament talks of Solomon’s Temple, known as Suleiman’s Palace in the Koran. It is said to be of timber, gold, ivory, gems, peacock feathers and sandalwood, all brought from a harbour called Ophir. The forests in the hinterland of this port had all these things. To me, Ophir was Beypore.

The entire structure of the Thekkae Kottaram is decorated with elaborate, minutely detailed carvings, revealing high mind power and advanced imagination. It’s a holy power. When a man dies, he’s gone. When a teak tree is cut down to make such fine work it continues to live. No one can carve like this anymore.

Kavitha, Padmanabhapuram Palace, Tamil Nadu, India.

I was born in Phrae in 1951. At that time, we were forced to use Thai names, which we made up, so my mother became Darunee. My early memories are of us singing together and her telling stories about my grandfather.

My father had six wives. Dolly was his first. I had nineteen brothers and sisters, with other mothers in their own houses. As a child, I believed that my father really loved my mother. They enjoyed nature, songs and God, and lived a simple life reading books and appreciating trees and rivers.

When the Thai government took over the teak business, my family had to move house. Scott taught English and Dolly took care of the family.

At the time of Dolly’s death, she and Scott were the only Danish people living in Phrae.

For thirty years after that, my father kept my mother’s body in a beautiful teak coffin in the dining room. She was like a mummy, preserved in formaldehyde. When we moved to Chiang Mai, he used to open the coffin to talk with her every day. I heard him confess in front of her body about the other women in his life. His new wife was scared. Eventually, when he was over seventy years old, we persuaded him to bury Dolly in Lampang.

After I got married, I returned to Phrae to look after the family houses and my father towards the end of his life. I tried to understand why he had so many wives. He explained, “All these girls said they loved me, so why should I love only one?

When they said, “I love you”, I had to say, “I love you too.””

When Scott died, we moved Dolly to Chiang Mai to bury them together.

Tin Thit | Poet, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar

My village Kyi Daung Kan was once surrounded by rich teak forests. Now it’s all gone.

The forest was an ideal hiding place for Burma Communist Party fighters and it also harboured malaria mosquitoes. These are the reasons the military government gave for cutting them down. Companies overseas related to the junta bought the teak and would change the name of its source in Singapore.

In the past, traditional shifting cultivation or taung-ya converted forests to agricultural land, but that was a system of rotation and temporary land use. Balancing customary laws with statutory laws is a challenge. The government must let local people use the forest. We must respect the rights of indigenous people to own resources, forests and land.

Land ownership problems are also related to crony capitalism. Land is an asset in their books. It has potential for future projects and they can sell it illegally. Companies seek big pieces in places such as the Pegu Yoma just for the sake of owning them, not for producing anything.

How will land ownership issues be solved in insurgent areas when eventually there is peace? With or without peace, armed groups cut the forests and also get money from other natural resources. Illegal border trade creates instability. We need peace. But that can also spell trouble for the forests.

Local people don’t have much income, so often they become part of the problem. Deforestation causes poverty. Poverty causes deforestation.

Tun Sein Gyi is the number one elephant in this group. He is the leader, the largest and can pull about two and a half tons. That’s a big log. Trouble was, he squashed people.

Every working elephant in Myanmar has a logbook describing its life, spirit and character. Tun Sein Gyi’s book shows that he is presumed born in 1950 and was captured from the wild in 1969. We can learn that he got a tear of the ear in 1993 and in 2009, he killed a man. He has killed three people.

When Tun Sein Gyi’s u-zi retired, nobody else wanted the job. I was the hlan-kai or spear guy who follows on foot, so I was promoted.

When dark liquid comes out of the holes behind his eyes, I know he’s in musth. Young male elephants especially are dangerous at that time. During musth, I take Tun Sein Gyi to a corral far from the village and tie him up. I visit twice a day and feed him just a little. He is in musth right now, so no one else can go near him.

Am I brave or silly? It’s like the dogs in my village. Other dogs, I’m afraid. But my dog is dangerous to other people.

Traditional teak extraction is still practised in some forests of Myanmar. Long Chon Reserved Forest, Gangaw, Myanmar.

Demand for wooden cargo vessels by Gulf countries wasn’t so great once oil was discovered. These days people are making urus as pleasure boats. Most rich people want high-tech boats but rich Arabs also want tradition and an uru tells the story of their ancestors.

Now we are five brothers doing this business together. Mostly we deal with coastal people in Kuwait, Bahrain, Yemen, Muscat, Dubai and have connections along the coast of Iran. Many places. Mombasa, Zanzibar, Aden. We are friends there.

Teak is like gold. We once had our own forest but it was nationalised. Now we buy teak at auction from forests that the government manages, private plantations and also import some from Malaysia. We built a hundred-and-fifty-foot dhow for Crown Prince Sheik Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani and eight or ten dhows for other Qataris last year. When we make boats for a royal family, they only want teak. My son used to say, “Baba, this is an old business,” but now he’s getting respect in Qatar as part of a dhow-making family.

SS Pegu was torpedoed off the south coast of County Cork, Ireland, while carrying Burmese teak to Liverpool for heavy gun emplacements in 1917. Some eighty tonnes of excellent condition half-metresquare baulks of six or more metres were retrieved from silt beneath the Celtic Sea in 2011. Surfacegribbled leftovers have been crafted into bowls, benches, sculptures and pens. Oxfordshire, England.

Detail of the front door jamb of a private residence in Kanadukathan, Tamil Nadu, India.

Chettiar merchants extended their reach under the nineteenth-century British Raj throughout much of Southeast Asia. Thousands of tonnes of carved Burma teak doors, pillars, beams and furniture grace their fortified palaces in South India.