PARACAS, THE CULTURE AND THE GEOGRAPHICAL AREA

Paracas is both a place and a more than 2000 year old culture in Peru. its special burial sites provide us with a rich selection of wonderful, thought-provoking fragments.

The Paracas peninsula, a promontory on the coast of Peru, lies 156 miles south of Lima. The area is very special. Like the rest of the Peruvian coastline, Paracas is a desert. There, the cold currents flowing from Antarctica meet the warmer streams from the north. The confluence of these streams by the peninsula and outlying islands create a nutritious water environment, attracting an abundance of fish, sea creatures and birds of different species. The area is well known for its rich wildlife. Nowadays a lot of tourists visit the area and they take boat trips out to the islands off the coast to see the rich local fauna.

Tucked in by the coast, where there is a protected bay of warmer water is an area comprising several burial sites. Many highly significant finds have come out of these sites, from burials dating back more than 2000 years. The desert landscape here is exceptionally beautiful, with huge sand dunes displaying a palette of pinks, yellows and lilacs.

Visiting this place and beholding its beauty was very moving for me, as I had lived all my life in a country where vegetation is plentiful. Yet it was hard to take leave of the place because of its special light, colours and atmosphere. It is impossible to imagine how this place would have looked thousands of years ago, but it was in all probability as fascinating then as it is today.

The graves were created to preserve the people who lived in this culture. The burials took place during a period of one thousand years. Parts of their textile story have now appeared and today provide us with a wealth of study material.

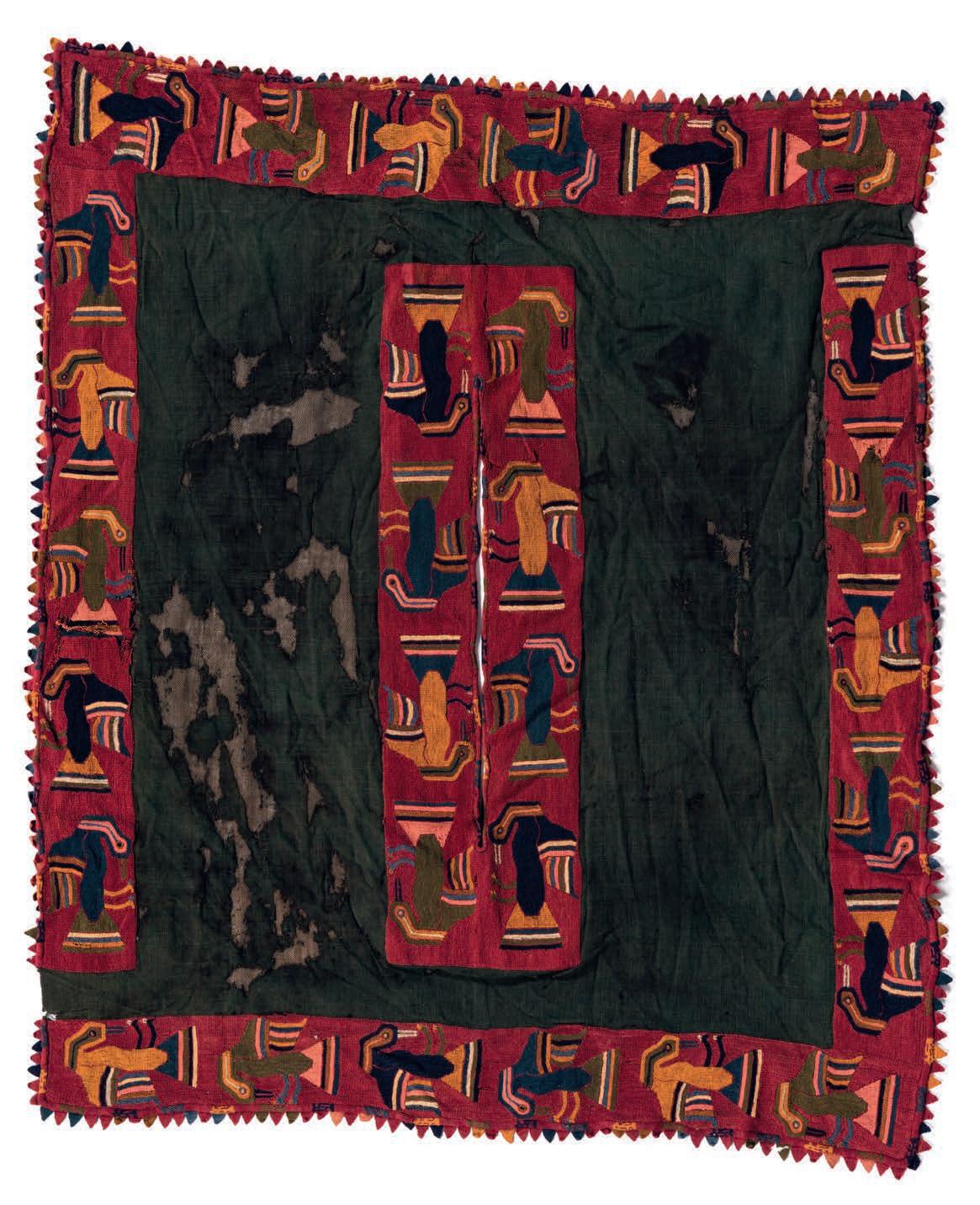

The Paracas textiles, that have been held at the Museum of World Culture in Gothenburg, for about 100 years, are characterized by thin, fine yarn in bright colours embroidered on plain weave fabrics.

Lima Paracas

PERU

arranged picture: part of a turban with two spindles and a needlecase.

sketch made in the 16th century, inka period. one woman is spinning and the other twining threads.

evaluated and assessed nowadays. We value what we can actually see, not the invisible work. What we should question is how long it took to prepare the fiber, the raw material, then spin and ply all the yarn required for weaving and embroidering the textile.

Nevertheless, questions to do with duration are impossible to answer, since timing also depends on the experience and skill of the artisan as well as other working conditions.

Moreover, the concept of time is different in non-industrial cultures compared to ours: the result is what counts, not the time spent.

Worth considering too is the notion that work should not go too fast and that work, just like life, should follow certain rhythms.

People who grow up in cultures where craft is practiced on a daily basis, learn to appreciate the quality, processes and connection of one stage to another, even if they do not practice that particular craft. Often it is a person from the same cultural background who can best understand and evaluate the outcome. No one questions the time needed.

Another question might be about whether the work was carried out by professional artisans and/or on a piecework basis.

Professionalism today generally implies a full-time occupation and that the practitioner receives some kind of remuneration. Conclusive answers will not be forthcoming here either, even though such questions are of interest from today’s standpoint.

All we have are the actual fabrics as we see them today. We can try and understand the technical processes and in so doing, possibly “catch sight of” the woman behind the work.

In the case of piecework, if that were the system, this would have been carried out in much the same way as in other artisan commodity cultures up to the present time. The women, assuming it was primarily women who spun and wove, would most certainly have taken a break from spinning or weaving when it was time to cook, fetch water or carry out other tasks.

In asking women from various other cultures how long it took, to spin and weave a large carpet, for example, I have been told that it took a winter to weave. How long it took to spin the yarn was impossible to say: spinning was a work in progress more or less all the time.

different shades of colour-grown cotton cultivated in the nazca region.

a woman, preparing cotton in a different way. she is beating the cotton into a quadratic form before she starts spinning.

Despite the stark effects of industrialization on cotton production over the last couple of centuries, with the demand for totally white cotton as a production base, cotton cultivars still exist with different shades of colour and in various qualities.

Cotton can range from dark chocolate brown to pink: these shades are common in the museum’s other pre-Colombian textiles.

Nowadays the dark brown fibers are short and very curly, which makes them hard to spin, but the lighter brown they are, the longer the staple length of the fiber tends to be.

The fact that cotton was not white originally explains why the Paracas textiles woven with cotton thread have their characteristic colours. The most common shade seems to have been yellowish beige, but there are also light and deeper brown textiles. This naturally pigmented cotton can be dyed, particularly well with indigo.

Cotton has only been used for weaving.

When Columbus first set foot on the shores of South America, the story goes, he was presented with a splendid gift, a ball of yarn spun from white cotton.

This story tells us two things: first, that textiles and textile materials were highly valued and secondly that white cotton was considered to be especially valuable. White fiber has always been prized, as there are few naturally occurring white fibers that can be used for spinning. What is available has usually been through a process of domestication, of a refinement.

Today’s industrial demand is solely for pure white fibers to produce textiles in bright, clean colours using modern synthetic dyestuffs.

contemporary balls of 2-ply cotton yarn. colour-grown cotton can even be deep brown.

a woman in aricipa pulling alpaca fiber apart in order to spin a thin thread.

Many fibers are built-up in different layers where every other is placed in s or Z-slant.

In regards to yarns used for embroidery, it does not need to be tightly twined as one can spin the needle whilst sewing. This allows for custom tightness according to the craftsman’s desire.

Considering the amount of work involved in preparing fibers for spinning, spinning a single thread and then plying it, it is understandable that the durability of the yarn was of great importance.

This shows a profound respect for the whole process and it is a lengthy creative procedure, just like the stirring of life into being, in the plant world as well as in all living creatures. Once again, it is fully understandable that spinning was a symbol for the beginning of life.

Weaving yarn needs to withstand the strain to which it is subjected during the process of weaving.

The embroidery yarn needs to hold while being stitched through the ground cloth.

The quality of yarn depends on how tightly or loosely it has been spun and plied. Many textile researchers and artisans try to count the number of plying turns in a yarn in order to determine its quality. This is next to impossible to do with handplied yarn and irrelevant since working that way never was an option for the spinner.

We must learn to evaluate quality as an entirety and look at the thickness of the fibers, preparation methods, spinning and plying. We need to assess the yarns as produced by a particular individual. Unfortunately, the industrialised “mindset” has influenced us so profoundly that we seem to have “forgotten” the origins.

In the industrial world, you attune the spinning tool to count the number of turns for a certain quality, e.g. the number of turns per metre. During preindustrial times this was instead dependant on the skill of the hand and the good eye. It was not a matter of quantity, but of human trained skill.

a woman from a mountain village in Peru picks and pulls out alpaca fibers into a thin ribbon for spinning.

Such thread will not be that long, since there is nowhere to wind it as it is spun. It is also easy to produce “over spun” thread, that is with such a high twist per unit of length that it twists itself upon folding over itself.

When the women has spun a thread-length, she can thread it directly through the needle’s eye, then put together the thread ends, the excess twist in the thread will then suffice to twine the thread into a 2-threaded thread. This means to say she has a 2-threaded thread that lies as a single thread through the needle’s eye and is of sufficient length to sew.

Thread made without the use of spinning equipment

This is a method I have seen used in various places, including Kurdistan and Kyrgyzstan, but it has also been practiced in Scandinavia, in particular instances, like for stitching leather.

a Kurdish woman spinning a thread with her bare hands.

It could be objected that this method would not accord with the Paracas fundamental practice of never breaking or damaging a thread, as the thread when finished would have to be cut in order to remove the needle. Theoretically, since the needles were made from cactus spines, which were in great supply, the needle would have simply been snapped in the needle’s eye. Then a new needle would be threaded up with a new thread.

A subsequent question – how does one splice and join a thread like this? If the described method is used, a new thread could be passed through the final loop of the previous length of thread. This type of joint would be invisible.

A different joint applies for loose ends, whereby the unspun tails are overlapped and then twisted tightly together to splice them. See page 139.

Interesting as these methods and conjectures are, we cannot say with any conclusiveness if and how they were used. It is extremely hard to find traces of these types of joins in material as old as this. It must first be established that these possibilities exist before they can be looked for.

Another point of great importance to the production of textiles is the accessibility to fiber. The art of quantifying fiber material is as important as knowing the thread-length. If the yarn

a few extremely thin spindles with wheels for spinning over rod.

a woman from croatia spinning over rod, where fibers are pulled out and “jump off” the sharp top of the spindle. You need to keep a steady hold of the spindle the whole time.

already plied yarn resulting in the stretching of the fibers.

It is easier to use this kind of spindle and it is now by far the most common method in the world. The yarn becomes stronger in tension simply due to the fact they are spun in tension. It is significantly easier and faster to spin this way, however it results in a completely different quality – not as thin as those made with a supported spindle.

These two different methods of spinning, with either a drop or a supported spindle, are practiced in most countries and cultures throughout the world where women still work according to long established traditions. I have myself witnessed both methods used in Turkey as well as Eastern Europe, Central Asia and Peru. Moreover, there are old drawings from artists and travelers in different countries of both methods of spinning.

A spindle rod or shaft has two functions: it provides the twist that transfers to the yarn and it is also the core around which the spun thread is wound. When spinning off the point, fibers are not subject to pulling movements. The act of the twist itself picks up new fiber into the spinning point. This also requires the fibers to be well prepared, it cannot be uneven.

Spindles with a small whorl are somewhat heavier. The work is thus easier for the spinner who does not need to make all the rotations herself. The whorl’s purpose is to keep the spindle in motion.

Both kinds of spindles can be found in the Museum of Ethnography’s pre-Columbian collection.

These spindles are made of ca 15 cm long cactus spines. A spindle will consist of two spines, turned with the stubby ends facing each other. The two parts are often bound together with the help of a small hollow straw where the cacti spines, sometimes with a cotton wads, are joined with some resin.

The sharp spindles with a little whorl can be assembled in a similar fashion, but there the whorl covers the joint. In spite of this, the whorls were relatively easy to move from one spindle to another.

The whorls were probably very valuable and they also symbolized the plied thread of life and the constant rotation of life. We can still see that small pebbles and other similar

close-up of a variant of stem stitches. here the stitches do not slant but have been sewn in parallel. see sketch on page 155.