Sommario

Giacinta Jean, Alberto Felici The Success of Stucco Decoration Across Europe and the Role of the Plasterers

20 Note sull’uso dello stucco a Milano tra fine Quattrocento e primo Cinquecento

Jessica Gritti

33 Domenico Fontana and the Art of Stucco: Roman Building Sites

Serena Quagliaroli, Giulia Spoltore

56 «Cartellami, camei, grotteschi, e altri simili stravaganze»: protagonisti e modalità della diffusione della decorazione in stucco a Genova tra XVI e XVII secolo

Roberto Santamaria

75 Salzburg as an Early Centre of Ticino Stucco Work

Manfred Koller

82 Techniques and Market Conditions: Stucco Masters in German Countries in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

Barbara Rinn-Kupka

96 Interior Stucco Work of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries in The Netherlands

Wijnand Freling

109 An Introduction to Danish Stucco Decorations c. 1550–1750

Casper Thorhauge Briggs-Mønsted

128 The Profession of Stucco Maker in Seventeenth-Century Lesser Poland

Michał Kurzej

143 La dicotomia tra scultori e stuccatori nella plastica tardo barocca romana: il cantiere di Santa Cecilia in San Carlo ai Catinari (con una nota sui restauri della sala Regia)

Vittoria Brunetti

160 Stucco Decoration in L’Aquila in the Second Half of the Seventeenth Century: Projects, Designs and Masters

Carlotta Brovadan

The Art of Stucco Making: Materials and Workmanship

182 Qualche esempio sull’uso del disegno nelle pratiche di bottega degli stuccatori lombardi e luganesi

Massimo Romeri

207 Materials and Constructions: Stuccatori at Work in Basso Ceresio. Archival Sources and Material Evidence

Giacinta Jean, Alberto Felici

237 Attraversare il Settecento con gli stuccatori Portogalli: organizzazione del lavoro, materiali e strumenti

Mickaël Zito

Case Studies

254 Fontainebleau 1530

Oriane Beaufils

277 The Collection of Renaissance Stucco Statues at Bucˇovice Castle. Technologies, Techniques, and Materials Used

Veronika Wanková, Renata Tišlová, Peter Majoroš

294 The Stuccoes in the Church of the Annunciation to Mary in Kostanjevica at Nova Gorica

Marta Bensa, Katarina Šter, Sabina Dolenec

305 Leonardo Retti a Roma: la decorazione in stucco di Santa Marta al Collegio Romano in collaborazione con Antonio Roncati

Carla Giovannone

328 The Stuccoes in the Church of Los Santos Juanes in Valencia (1693–1702)

Gaetano Giannotta, José Luis Regidor Ros

339 Baldassarre Fontana in Cracow

Michał Kurzej

358 Gli stucchi di Baldassarre Fontana, primi appunti su tempi d’esecuzione, materiali e tecniche: lo studio della Galleria degli angeli del castello di Uhercˇice

Alberto Felici, Jana Zapletalová, Marta Caroselli, Giovanni Nicoli, Medea Uccelli, Jan Válek

374 Glossario tecnico / Technical Glossary

385 Abstracts

397 Indice dei nomi / Index of Names

decoration of the chapel was completed in several stages between 1691 and 1692, with the stuccatori actually being present on-site for about ninety days (allowing for some absences and a long winter break).9 The work was carried out directly by Agostino, aided by a worker and his son Gianfrancesco, who was left with orders when Agostino departed to guide other construction sites. In Civo in Valtellina as

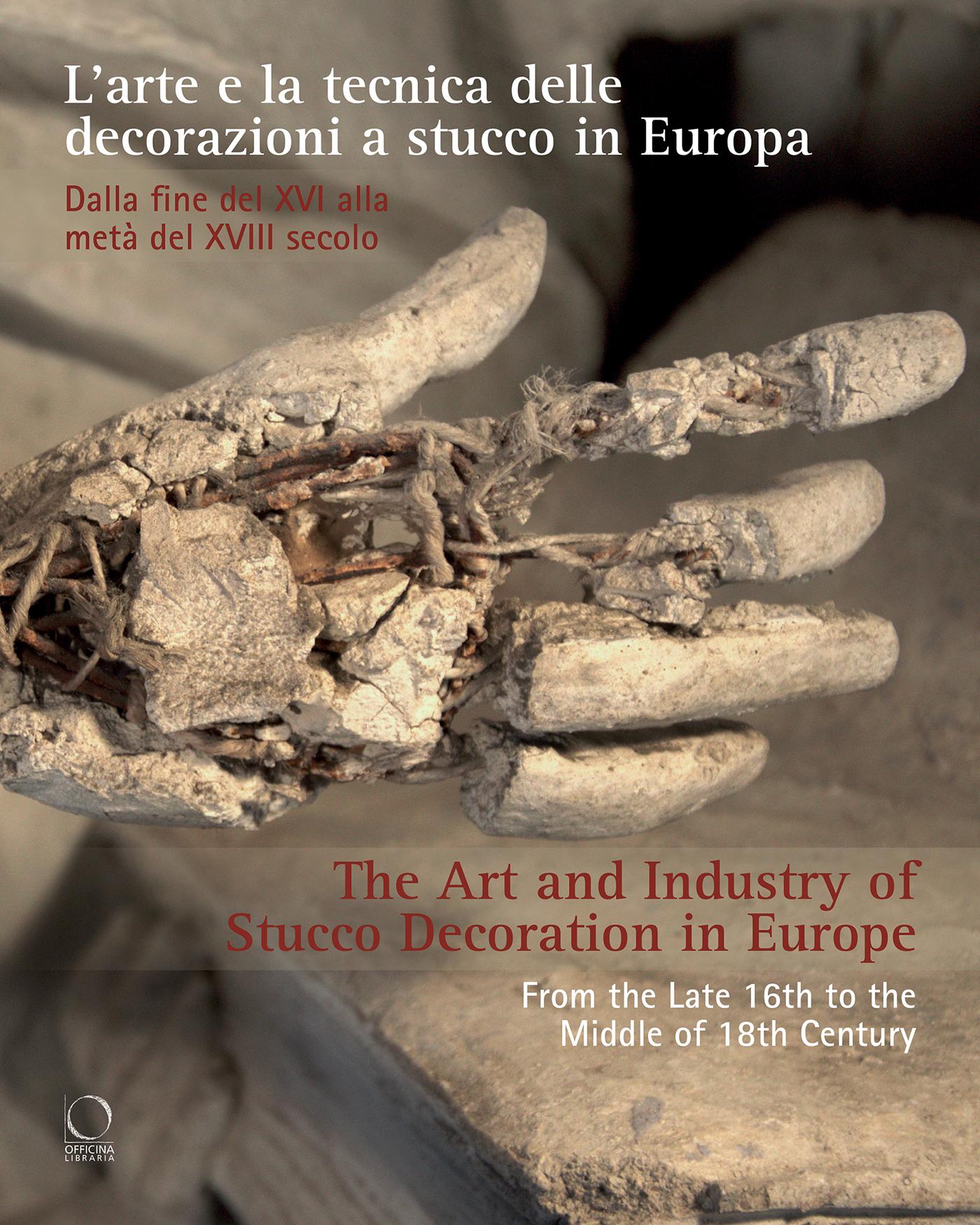

fig. 1 Domaso (Como), Church of San Bartolomeo, Parish Archive, Cartella ex-Matrimonialia, ‘Note of expenses being made by Canonico Manrico and by Canonico Passalaqua for the stucco of the Chapel of Saints Francis and Anthony in the Church of San Bartolomeo of Domaso [...]’, 25 September 1691.

well, the accounts register for ‘adorning with stucco the chapel of the Madonna in the Church of Sant Andrea’ allows us to reconstruct the working days of Agostino and his son.10 Work begin on 30 August and was finished on 29 November 1695. The father opened the building site, then worked with his son for fourteen days; subsequently, the two alternate their presence on site over about the same number of days (in three months, the father and son registered a total of 109 days).

In Domaso, the patrons undertook to provide all the materials needed for the work; to pay the masons for the work ‘that needs to be done’ and for scaffolding; to pay a garzone11 to crush the gypsum; and to prepare the material for the stuccatori; and finally to supply wine and lodging – a ‘house with its beds’ – for Silva and his team throughout the work. These documents sometimes mention tools for plastering or building work. Notes are found on the purchase of paint brushes and sieves required to sort the aggregate by grain sizes,12 and orders to the carpenters for the ‘modeni’, or profiles, for establishing the shapes of the frames, and the moulds for serial decorations.13 The wooden and metal spatulas for working the stucco, on the other hand, are never mentioned: these were evidently part of the valuable personal baggage always carried by each stuccatore. 14

The conditions contained in this contract are largely repeated in the documents consulted in other cases, indicating that the practices were fairly widespread. In 1683, among the papers relating to the apsidal semi-cupola of Careno parish church, the materials that the stuccatore would use are also indicated in a comprehensive ‘shopping list’.15 In fact, reference is often made to ‘notes’ of materials delivered by the stuccatore to the clients, but no trace of them remains in the archives. In the case of Careno, the commissioning party, represented by the men of the community, was obliged to administer to the said Silva all the materials that shall be needed for said work, that is, lime poured as it should be, fired and crushed gypsum, marble powder and irons, and other items that will be needed for serving of the said work as may additionally be necessary to give to the mason, both for making the scaffolds, and for masonry of the altar and plastering in accord with what will be needed, and as the works go on they are obliged to give a Garzone to serve, as also beds and rooms and wine.16

fig. 2

Domaso (Como), Church of San Bartolomeo, Chapel of Saints Anthony Abbot and Francis, 1691–2, stucco decoration by Agostino Silva, wall paintings by Pietro Bianchi.

figg. 6a-b Cavallasca (Como), Imbonati Oratory, base of the pillars.

fig. 7

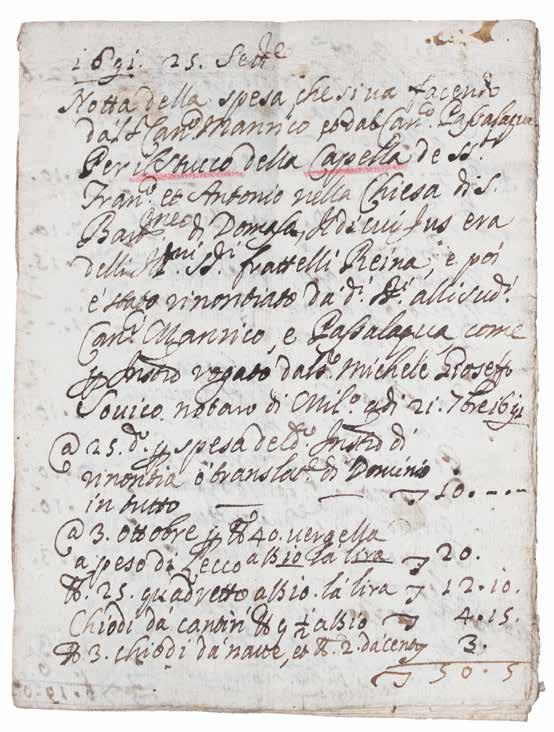

Examples of friezes and cornices of buildings constructed with moulded bricks . From A. Capra, Nuova architettura civile e militare (Bologna: Giacomo Monti, 1683, Lib. II, p. 86).

figg. 8a-b Cantù (Como), Church of the Transfiguration, round bricks used for more rapid shaping of the volutes of the column capitals.

The documents do not indicate the dimensions of these elements. In the construction of the overhang of the upper cornice of the Imbonati Oratory in Cavallasca, two types of bricks were found, both 4.5 centimetres thick but of two distinct lengths and widths: some 24 × 13 centimetres, others 33 × 17 (fig. 5). 35

The better the profile of the supports matched the final one, the easier and faster was the work of the stuccatore. For this reason, both in direct observation of the works and the references in treatises (and at Valenza also in archival documents),36 we see torus (with a rounded end) bricks used in the bases of pillars, to guide the application of the stucco on the moulding, and round bricks for more rapid shaping of the volutes of the column capitals (fig. 6a, b, fig. 7, fig. 8a, 8b). 37 More often, however, the

definition of the forms to be finished with stucco was improvised, using the available materials in the most ingenious way; see, for example, the acanthus leaves of the capitals of the Imbonati Oratory in Cavallasca, built with a curved piece of tile, to achieve the concave projection, attached to the masonry with a large nail (fig. 9).

If necessary, the edges of the bricks were smoothed with a small hammer. This was done before placing them, in cases where the brick would be completely bedded in mortar,38 or afterwards, in cases where the edges remained exposed (fig. 10) Cherubini describes this typical process as ‘scartà il quadrell’ or ‘smussà il quadrell’ (trimming or rounding the bricks). Observations at Cavallasca and Cantù revealed that the bricks of the top cornice had been chamfered to create a groove, but no comment on this operation has been found in the archival documents, probably because it was a part of all those works performed by the apprentice who assisted the stuccatore in his operations.

The documents – between about 1650 and 1700 – indicate highly variable brick costs, probably dependent on the economic situation, the size and quality of the bricks (new, salvaged, well-fired or defective), and perhaps also on the quantity of the supply.39 The cost of the flat tiles, on the other hand, is decidedly higher: the 160 ‘quadroni di pavimento’ arriving at Castel San Pietro from Coldrerio in 1690 cost 5 lire (meaning 3 lire and 6 soldi) per hundred, and the ‘tavelle’ (‘pianelle’, flat tiles) that arrived at the church of Domaso in 1691 cost just under 3 lire per hundred: prices about twice as high as simple bricks.40 Some documents also report how many bricks were needed. For the structure of the altar and the core of the statues of the Chapel of the Blessed Virgin in Valenza Cathedral, the purchases were: 1700 stones (bricks), 400 pianelle, 100 tavelloni, 100 quadroni and 10 quadroni da scala (shaped elements perhaps used for the entablature).41

fig. 9 Cavallasca (Como), Imbonati Oratory, the acanthus leaves of the capitals built with a curved piece of tile to achieve the concave projection.

fig. 10 Cantù (Como), Church of the Transfiguration, upper architrave.

fig. 17

Castione Andevenno (Sondrio), Church of Saint Martin, pieces of window grate used for anchoring the stucco decoration to the wall.

fig. 18

Cantù (Como), Church of the Transfiguration, detail of the complex iron and wooden armatures.

clearly a less expensive option but lacking the flexibility to follow the complex shapes of the moulding (fig. 18).

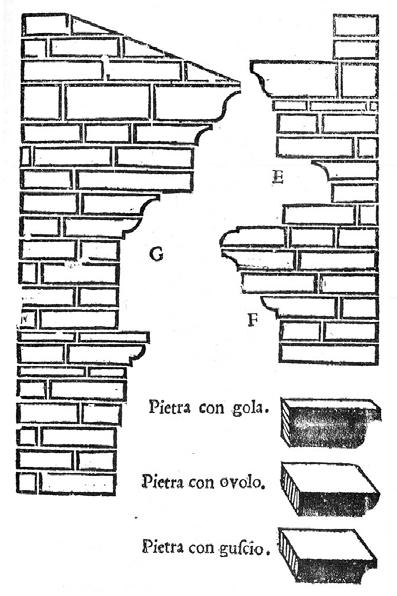

The Domaso documents also mention the purchase of ‘ordinary and coarse’ iron wire, with indication of cost, but unfortunately not the quantities. The use of reinforcements consisting of iron wire of different sizes relates to the type of modelling: for example, wire is used in cases where the decorative elements have pronounced

volumetric and sculptural qualities and are not directly anchored to the support, such as the fingers of the statues, and in the Imbonati Oratory in Cavallasca, the ribbons that connect the volutes of the Ionic capitals with the central festoon of fruit. The fall of some of the modelling has revealed that these festoons were reinforced using a bundle of four or five iron wires (fig. 19).

The records for the Civo site of 1695 provide rare notation of a potential purchase

fig. 19 Cavallasca (Como), Imbonati Oratory, the festoons of the capitals are reinforced using a bundle of four or five iron wires.

fig. 20 Cantù (Como), Church of the Transfiguration, detail of the nails supporting the stucco decoration.

fig. 5

Rosso Fiorentino (and workshop), The Young Roman, stucco, Galerie François Ier

makers prepared a mortar, mixing hydraulic lime with sand, and crushed brick, giving the material a pinkish tone.38 This mixture served as a core around which the stucco artist shaped his actual model. The modelled material was finer, mixing a slaked lime – more plastic, slow setting and therefore easier to work than the hydraulic lime – with finely ground limestone. This material was applied wet on the core in successive layers to progressively shape the sculpture. Low reliefs followed a similar process. Stucco makers worked directly on the wall. Here again, they used nails at various depths on which to position each of the sculpted reliefs. The nail heads are still visible on some of them.39 Each individually modelled figure on these reliefs is, in a way, freestanding, not connected to them which explains the complete detachment from the support of the (very rare) missing elements (the Venus in the shell beneath the Defeated Ignorance, for instance).

This recipe for a brick stucco is surprising in early sixteenth-century France. Stucco was well known among artists in antiquity, but was a relatively recent rediscovery, with which both Rosso and Primaticcio had familiarized themselves during their Italian careers.40 The popularity of this technique had been revived in Raphael’s workshop and it had been rediscovered, according to Vasari, by Giovanni da Udine himself, who added powdered marble to the lime mixture and had managed to obtain the much-desired whiteness of antique stuccoes.41 Thus, early cinquecento Roman stuccoes all present a grey-white core, unlike the pinkish-coloured ones at Fontainebleau. After he left Rome for Mantua in 1524, Giulio Romano, assisted by the young Primaticcio, pushed the limits of stucco’s plastic possibilities, but did not use ground brick to harden the core of the Palazzo Te decorations. Yet the introduction in Mantua of high-relief figures (in the Camera degli stucchi, the Camera delle Aquile, or the loggia of the Giardino Segreto) would have required a sturdier core than those of the smaller Roman low reliefs. Analysis conducted between 1984 and 1990 has shown that the material consists of a common mixture of lime, sand and ground stone, with gesso as an additive and powdered marble.42

Admittedly, brick-lime stucco was not entirely new, but its use dated back to Florentine work in the quattrocento, which was a constant source of inspiration for Rosso Fiorentino. Indeed, this technique is well documented in Donatello’s work. His colossal figure of Joshua, intended for one of the buttresses of Florence cathedral and executed between 1410 and 1412, was described by Vasari as a sculpture ‘di mattoni e di stucco’. Was it a solid brick-based core coated with a superficial, thinner layer of stucco, simply mixing lime with sand?43 Or was the whole figure made of a mixture of brick and lime? Though Vasari’s use of the word ‘stucco’ remains polymorphic, at least it shows that the combination of these materials was considered efficient in the context of free-standing sculpture creation. The tradition of using brick with stucco continued throughout the fifteenth century.44 Agostino di Duccio was asked to create a pendant sculpture for the opposite buttress: here again, the colossal statue is composed of a mixture of brick and lime.45 Stucco statuary established its prestige at the

fig. 6

Rosso Fiorentino (and workshop), The Philosopher, stucco, Galerie François Ier

fig. 7

Rosso Fiorentino (and workshop), Ignudo, stucco, Galerie François Ier, detail.

beginning of the sixteenth century, no doubt when ephemeral creations were required from artists for city pageants. Quickly implemented, cheaper and imitating the visual effect of marble, stucco bent to the requirements of the increasingly lavish celebrations in Medici Florence. The most famous example is the entry of Pope Leo X into Florence in November 1515. Rosso Fiorentino, still in the early stages of his career, was entrusted with the execution of a triumphal arch on the Canto dei Bischeri and its decoration with garlands of fruits was among the highly praised realizations of the pageant.46 On this occasion, Baccio Bandinelli created a monumental stucco figure of Hercules, which was greatly celebrated. A few years later, the same artist sculpted two large stucco figures, probably on a brick frame, for the garden of Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici in the Villa Madama.47

This recipe was also used for low reliefs. Donatello resorted to this specific blend in

fig. 14a-b

Rosso Fiorentino (and workshop), Putto flanking the Loss

and putto placed at Gallery extremity.

of the Perpetual Youth

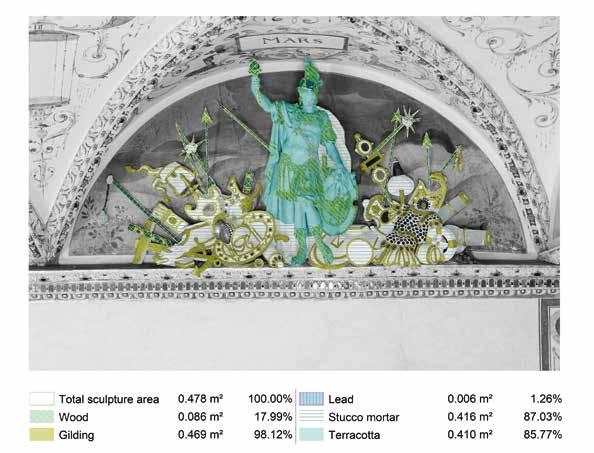

sculpture and the materials used – the sculpture of Mars is the only one with a terracotta core, composed of at least six parts that were connected by nails and wooden pegs, and joints filled with stucco. The shape of the sculpture was then completed by covering the terracotta core with white stucco, whose composition corresponds to that of the other sculptures in the Imperial Chamber. It was in this way that the drapery of the tunic and cloak, which also covered the joints in the terracotta core, was completed (fig. 2).

At this stage, the statue of Mars was evidently lifted up into the lunette, with the background already plastered, and attached using rods or nails. After Mars had been fixed in place, the composition was completed by creating two groups of war trophies in stucco on the left and right sides of the statue. Then the decoration was finished and unified by covering the rods on the reverse side of the statue with coarse mortar.

An important finding, which may be evidence of the older origin of the terracotta core of the statue of Mars, is the discovery of older defects in the terracotta. It may thus indicate that it was earlier used for another purpose or relocated. It cannot be ruled out that it may previously have served as a model in a sculptural workshop or been exhibited in another setting, and its location at Bucˇovice may not be the original one. After placing the statue at Bucˇovice, these defects were subsequently

fig. 2

Reconstruction of materials on the figure of Mars.

overlaid with stucco mortar that filled the damaged or missing details of the terracotta and finished the surface. The same stucco was used to finish draperies and model the trophies.

The sculpture of Mars was restored by the Faculty of Restoration of the University of Pardubice. Thanks to detailed investigations which preceded the restoration,8 it has been shown by means of a stratigraphic probe that the surface of the sculpture of Mars was finished with polychromy applied in three separate stages. The oldest surface finish, which was certainly applied at the time the decoration was created, consists of a white lime wash with a thickness of 0.1 mm, providing a uniform surface for the terracotta and stucco parts on the Mars statue as well as the decorative parts of the lunette (the drumhead, cannon, ammunition for the artillery, and some parts of the wooden attributes (a torch and war trophies). Below this coating, any minor defects in the terracotta were retouched using a pinkish putty imitating the appearance of the terracotta. The same repair material was used to fill in the joints of the different terracotta parts of the sculpture.9 The colour finish applied over the white lime coating was transparent to semi-transparent ochre paint reaching pinkish flesh tone on the body of Mars (fig. 3). 10 In addition, ochre is also found on the stucco decoration of the ribs of the vault, where ochre is stratigraphically the first layer on the stucco substrate. However, so far ochre paint has not been found on the other sculptures in the Imperial Chamber and thus the original colour concept for the stucco decoration remains unconfirmed, although the extensive findings of ochre coatings could indicate that the stucco decoration originally looked different to how it does at present, perhaps in a combination of white and ochre.

fig. 3

Stratigraphic probe of the surface layers on the breastplate of Mars: terracotta (T1) with primary limewash (V1), and ochre paint layer (V2). Secondary treatments: chalk-glue ground (V3a) with imprimitura (V3a/b). 20th-century limewash (V4).

The ground and the finish layers differ in composition and their microstructural characteristics. However, differences among statues are to be found in the composition of the ground layers, for which two types of mortar have been found differing in structure and composition, which influences their colour. A pinkish-ochre ground layer was identified in the statue of Diana; here the mortar was a mixture of aerial lime and medium sorted pit sand rich in quartz, with a minor admixture of powdered

figs. 4-5 X-ray image of internal reinforcement of Europa’s arm and chest. The measurement was performed in cooperation with the Czech Academy of Sciences, The Institute of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics.

fig. 6 Europa: the detail showing the fastening of the figure of the bull to the lunette using wire rods and spikes.

fig. 7

Detail of the modelling of Europa’s drapery showing gilding and glass incrustation.

fig. 8

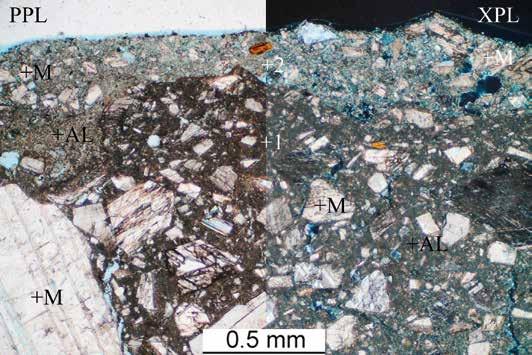

Polished thin section of marmorino taken from Europa statue. The marmorino consists of two layers (+1-2) both composed of aerial lime in binder and well sorted crushed marble as an aggregate. Description: AL – aerial lime, M – crushed marble.

marble dust and crushed brick (cocciopesto) with minor glass fragments. A characteristic component is an admixture of animal hair, which could have had a special purpose in reducing contraction when larger volumes of plaster dried out.22 A second, grey type was found in the statue of the bull which carries off Europa. This mortar contains the same lime binder but an aggregate mixture composed of blacksmith waste (charcoal black, iron scales and slag) and quartz sand, with a minor admixture of marble powder and brick dust. Unlike the pinkish ground layer in the statue of Diana, the aggregate of the grey mortar is well sorted and mostly fine to medium-grained with a maximum grain size of 1 mm.

Unlike the ground layer, the white layer of finishing mortar used for the final surface of all the statues and busts is characterised by a unified composition, with the same formula being used in all cases including Mars. The composition indicates the presence of aerial lime (with no gypsum admixture) and medium sorted marble dust. The lime binder was prepared from limestone and not marble as is evident from the preserved underburnt limestone fragments (fig. 8) 23

After the sculptures had been covered with a white finish, a third, extremely heterogeneous type of mortar was used to cover the fixing system on the reverse side of the sculptures.24 In the final phase, the sculptural decoration of the lunettes and the busts was completed with the addition of various details and other materials. Finishing touches were added to the terrain behind the statues in the lunettes in the form of natural features, pieces of blast furnace slag, stone, plants and shells, giving the appearance of the decoration of grottos. Wood or metal attributes were also used to complete the statues, the garlands and the laurel wreaths of the busts were made of polychromed and gilded copper sheets. A distinctive decorative feature, which we do not find elsewhere in Czech Renaissance stucco work, consists of various coloured pieces of glass used for the incrustation of the surface of the sculptures and the surrounding decoration (fig. 9). 25 A detailed analysis of the composition of the pieces of glass has shown that they originate from different periods.26 The oldest pieces of glass, which were evidently used for the original decoration, come from the period between the fourteenth century and the first half of the sixteenth century, and are probably fragments of stained-glass windows which have been reused here.27 The second group consists of pieces of glass dating from the period between the second half of the sixteenth century and the end of the seventeenth century.28 It is not possible to determine whether the pieces of glass in this group also belong to the Renaissance phase or whether they are later Baroque repairs. Finally, missing pieces of glass were replaced by restorers during the renovation of the stucco decoration in the 1950s.

The use of coloured pieces of glass served as a partial substitute for a colour finish, which was not found to any great extent on the stucco sculptures – unlike the statue of Mars. Colouring only occurs in a few places, in the form of lines or highlighting, for example, in the eyes of the emperors or the left eyes of Charles V’s horse (fig. 10). For this reason, even greater emphasis was placed on the rendering of the surface of

fig. 9

Detail of the glass inlay of the cornice, Imperial Chamber.

The various layers of the stucco employ different binders and aggregates: the ground layer in both samples is composed of lime and gypsum with carbonate and silicate aggregates; the finishing layer has only a lime binder with calcite aggregates. The two stucco layers bond well together, which indicates that they were probably applied wet-on-wet (‘fresco su fresco’ technique).12

The restoration of the stuccoes in the nave has highlighted the traces of the working tools, for example the marks of the spatulas, presumably made of metal,13 that were used to smooth the plaster, to define wings, hair, phytomorphic figures, the teeth of the putti and so forth. Some of the figures are fully three-dimensional, and some of their features, such as the pupils of the eyes, were probably highlighted with graphite or carbon black brushstrokes on the caryatids of the frame, or with a red colour on the caryatids in the choir. The analyses revealed traces of calcium oxalate in the top coat, meaning that the plasterer; could have finished the surface with casein or egg to achieve an even more authentic polished marble look than is evident today in the better-preserved areas.14

Stucco techniques and the materials used in Slovenia have not been studied systematically until now and these results will contribute to a better understanding of stucco decoration, providing an opportunity to situate stucco work in a wider cultural framework in the future.

fig. 8

Inscisions near the moulding of the decorative astragal frame and polishing of the surface.

fig. 9 Choir at the west end of the nave with sampling sites marked.