The Institute of Classical Architecture & Art is pleased to present the Lutyens Memorial Series as the inaugural ICAA Book of the Year.

The ICAA is grateful to the following sponsors of the Lutyens Memorial Series Volume 2:

The current and past Chairs of the National Board of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art are honored to pay tribute to Anne Kriken Mann’s tireless dedication to the Books Committee and the Classicist, which has been instrumental to the publications of the ICAA.

Russell Windham (2017–present)

Mark Ferguson (2014–2016)

Peter Pennoyer (2009–2014)

Anne Fairfax (2006–2009)

Gil Schafer III (1999–2006)

The ICAA also wishes to thank the following supporters:

Anthony “Ankie” Barnes

Curtis & Windham Architects

Matthew Enquist

Ferguson & Shamamian Architects

Jared D. Goss

Kirk Henckels

Kligerman Architecture & Design

Karen and Liam Krehbiel

Anne Kriken Mann

John P. Margolis, AIA

Oliver Cope Architect, LLC

Robert A.M. Stern Architects, LLP

Stuart Cohen & Julie Hacker Architects, LLC

Seth J. Weine

Bunny Williams

Paul Brant Williger

IMPERIAL DELHI

deed anything, which is so thoroughly satisfactory that all criticism ceases. In this case, though one may wonder how others estimate value, for oneself there is nothing to be said. One looks—one accepts—one marvels. Why is the great building which rears itself up in front of us so satisfactory? Why have our critical faculties suddenly ceased to function? No man worth his salt is not critical. Of course Sir Edwin had had a mighty opportunity. It was to be a regal building. Unquestionably he has succeeded. The Viceroy’s House would seem to express the perfect architecture which takes its stand on proportion alone. That is its decoration.’

These are important words, put with a charming modesty. The writer of them saw the building and at once understood. He was not taken aback by its plainness as some Indians were; nor by its lack of resemblance to any of the greater monuments of India as many British are. He was not shocked at its size as both British and Indians tend to be. Instead he hailed its magnificence with delight and rejoiced at the propriety of its style.

Consider first, then, the size of this palace. It is 630 feet wide and 530 feet deep from east to west. It measures 1030 yards round the whole of its basement plinth; that is, a little under two-thirds of a mile; and its whole area including internal courts is 210,430 square feet. As these are merely figures, Plate XXXVI has been prepared to show the comparative areas of two other great palaces. Versailles looks the largest but has in fact an area of 198,300 square feet with the courts of the wings added in. It is a narrow building though widely spread; and it has no broad and solid centre like the Viceroy’s House. The Palace of Westminster, however, is larger than both the others, for it gives a figure of 247,200 square feet if all the courts and Westminster Hall are included.

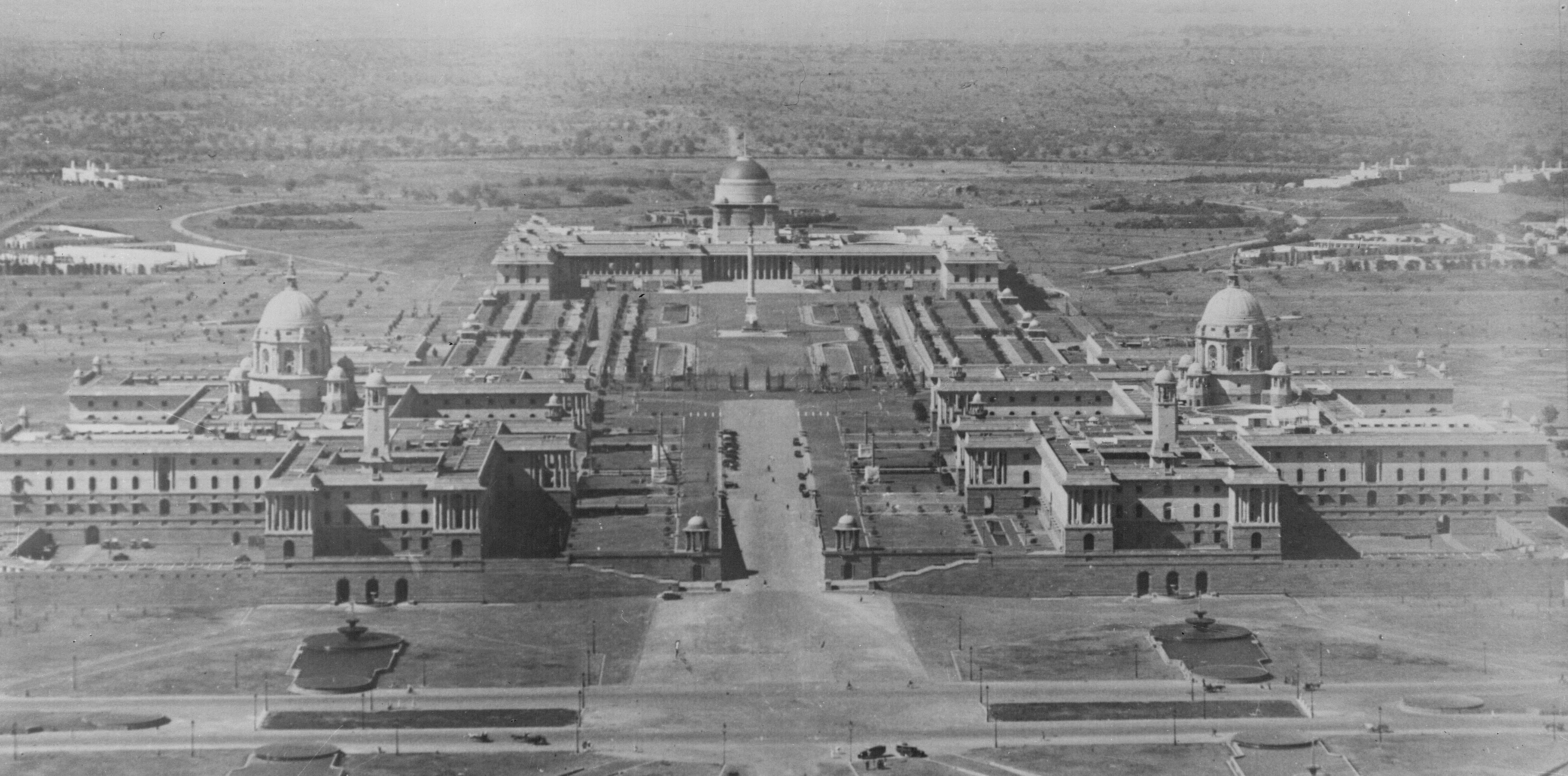

Now consider the size of the Viceroy’s House in relation to the other buildings on Raisina Hill. Figure 126 gives a better impression of this than the plans. For it will be noticed on that air-view that, though the palace stands 1100 feet back from the west ends of the Secretariats, it appears sufficiently big to dominate them. As well, the Viceroy’s Court in front of the House is kept throughout its width at the high level of the plateau and retained there by massive walls on its north and south sides; so that it seems like an extension of the House much more than a mere linking area between one building and two others. The dominance of the principal structure is brought forward, as it were, in a thrusting movement between the wings of the others. Lutyens may not have thought of the look of his work from the air; but this photograph certainly displays the skill with which he emphasized the supreme importance of his building both by making it very wide and by carrying a reflection of its form and its ordered composition down into and through the approach. It is impossible not to notice in this revealing view the unity in scale and in quality between the House and the Court and to appreciate their joint serenity in contrast to the rather speckled confusion of the foreground.

It is important to grasp the fact that Raisina Hill was originally a long plateau more than a small mountain, and that the Viceroy’s House straddles it towards its western end. That is the north and south fronts of the building rise from a lower level than the other two because they rest on the actual plain on which the hill stands. Figure 127, a view from the air looking north with Old Delhi in the distance, shows the south front and the way in which Lutyens continued his basement east and west to form the retaining walls of the Viceroy’s Court and of the enclosed and elevated garden respective-

ly. Figure 128 shows the north front with the same basement extensions from it. The view from the south-west on figure 129 is taken from a similar level as the last and illustrates well the high elevation of the lateral fronts above the plain. Figures 130 and 131, taken after completion of the road and gate piers, give closer views of the junction of the Garden wall and of the south retaining wall of the Court with the main building. Figure 132 continues the latter east as far as the interruption of the low level cross-road running towards the Jaipur Column (figure 202); and figure 133 shows the same point on the north side. Its attractive and remarkable detail will be referred to later. Figure 135 gives a fine view of the junction of the Garden retaining wall with the north-west wing and figure 136 shows the top of the corresponding wall on the south side. That photograph makes clear how high the Garden level is above the plain; and this is confirmed by figure 137 in which one looks west along the north flank of the Garden. Hence, therefore, the relative lowness of the west elevation (figure 138); and the same result—but one which does not detract from its splendour—on the east front (figure 139).

That series of photographs may convey an idea of the general shape of the building. Some notes on its plan-form come next. To begin with, it may be noticed that even on the roughly drawn block plan (Plate XXXVI) there is something which suggests deeply thought-out design giving an emphatic unity to the whole and—not only that—but a real vitality arising from its ins and outs and the inter-related masses they suggest. The diagram in the text is intended to assist an analysis of this. We do not propose to establish a theory on which Lutyens may have worked, because we consider that his designs were propelled by instinct at first and that, having discovered certain relationships which pleased him to look at, he cultivated them and, where practicable, forced his areas to fit. This palace endorses that view. It looks on paper singularly well-knit. There are no wandering extensions—not even balanced ones like the great wings at Versailles; nor is there that stringing together of romantic chambers and lobbies which constitutes the Houses of Parliament at Westminster and results in its dominating effect of length on one side only—an effect handsomely magnified by the reiteration of Gothic buttresses. The Viceroy’s House differs from that by having no reason to look long but, on the contrary, has to cumulate itself into a square form tending to be pyramidal and a little elongated on its north-south axis so as to grip the hill under it: a nearly square form, that is, which had to look equally well from all points of the compass. This was the initial item in Sir Edwin’s multiple problem.

Taking the diagram, then, it will be seen that the whole plan— except the excrescence of the north entrance—is contained within a rectangle C H I J. It is a short rectangle (640 by 536 feet) and, where its diagonals cross in the exact centre, the dome rises over the Durbar Hall (marked with a dotted circle). The sides of this enclosing form are in the relation of 5 to 4·75. Next, the dome is also the centre of a square form, A 1 2 3; and a second equal square overlaps this 40 feet further west. It is labelled B 1 2 3. The diagonals of this second square intersect over the throne against the west wall of the Durbar Hall and this overlap of 40 feet dictates the depth of the Portico, the west State Rooms and, as well, the thickness of the junction of the two smaller squares (G HK B1 and B2 LIM) attached to the main dome square at its south-east and north-east corners. The other two smaller squares at the south-west and north-west corners of the central block had of necessity to be equidistant from the dome

THE VICEROY’S HOUSE

north and south axis as the first pair. Hence the greater thickness of the junction BE in relation to the other B1 A1, with resulting value to the plan by allowing for a much elongated suite of rooms facing west and two colonnaded connecting loggias only to the detached wings of the east front. The sides of these four corner squares are in relation to the sides of either of the two major ones as 3 is to 4, a ratio which is displayed in the thickness of the wing (H O) as built. That is HO = ½ HK or ¼ B B3. Moreover, if the whole central rectangle (B A1 A2 B3) be measured, it will be found to have the same proportion in its sides (5 to 4·75) as the main enclosing rectangle of the whole building: and, as a corollary, if this central area be divided into 16 equal spaces (Q), they too have sides in that ratio. Two and

ic squares at the corners, one feels that those mythical forms relate them to the central mass and that the wings were, so to speak, carved out of flattened cubes. So, once again, on looking at this building in the solid, our sensation is akin to an appreciation of the finest sculpture. The original block of stone is there—invisibly behind the invented form. The knitting together of simple square and rectangular shapes in proportion, sensed by the percipient eye, is what fundamentally gives the thing life and the germ of loveliness.

The accommodation of the various departments of the Viceroy’s House within this symmetrical plan-form and the relation of each to the others as regards levels, access and cubic space is the next item

a half of these little units fit into the dominant area of the wings, as indicated on that to the north-east; and sixteen of them exactly fill the space between the wings of the east front. This does not occur in the recesses on the other fronts; but the void area D G B1 E, like its companion on the north—apart from the adventitious links across it—is again a short rectangle in the 5 to 4·75 ratio. And, finally, there are two still smaller rectangles within the square B 1 2 3 with their sides in the same proportion. These are marked by double lines. One contains the Durbar Hall and its narthex; the other the West Garden Loggia, the central staircase and the Long State Drawing-room. This kind of analysis might be carried much further, into deeper detail and the pursuit of related rectangles and squares; but the above may be sufficient to indicate the mathematical basis, founded on instinct, which infuses this plan. Though the wings are reduced in building to half and much more than half of the diagrammat-

to discuss. The sections drawn on Plate XLI have a bearing on this; and the four main levels should be clearly grasped. First, there is, at the bottom, the level of the plain, on the north and south of Raisina Hill, from which the building appears to rise on those two sides and grip the plateau. But, in fact, its roots were taken down to the plain level over the whole site—after considerable blasting and excavation; and the result is the Lower Basement. Plate XXXVII gives the plan of this. The main entrance to it is on the south side through the openings between the fat columns and arches of Indian detail which are seen on figures 145 and 147. That is, so to speak, the Tradesmen’s Entrance which gives quick access to the Kitchen and all its dependencies. There are other smaller ways-in on the north side (figure 171), but there are none at this stage on the east and west fronts of the House. Secondly, there is the level of the Viceroy’s Court and the Garden, on the plateau. This is carried through the

3. LAMBAY CASTLE, IRELAND: SMALL COURT

4. WEST FORECOURT

5. LAMBAY CASTLE: PERGOLA IN NORTH COURT

6. THE MEMORIAL

34. HESTERCOMBE: SOUTHWEST CORNER OF PARTERRE

35. LOOKING EAST FROM SOUTH-WEST CORNER

36. WALLED ENCLOSURE AT NORTH END OF WEST IRIS CHANNEL

37. HESTERCOMBE: NORTHWEST ROSE GARDEN, LOOKING SOUTH

38. ROTUNDA EAST OF OLD TERRACE

39. LOOKING SOUTH FROM THE ROTUNDA

46. STAIRS EAST FROM ORANGERY TO DUTCH GARDEN

44. HESTERCOMBE: FROM ORANGERY TO ROTUNDA

45. WEST END OF DUTCH GARDEN

47. HESTERCOMBE: DETAIL OF THE ORANGERY

48. INTERIOR OF THE ORANGERY

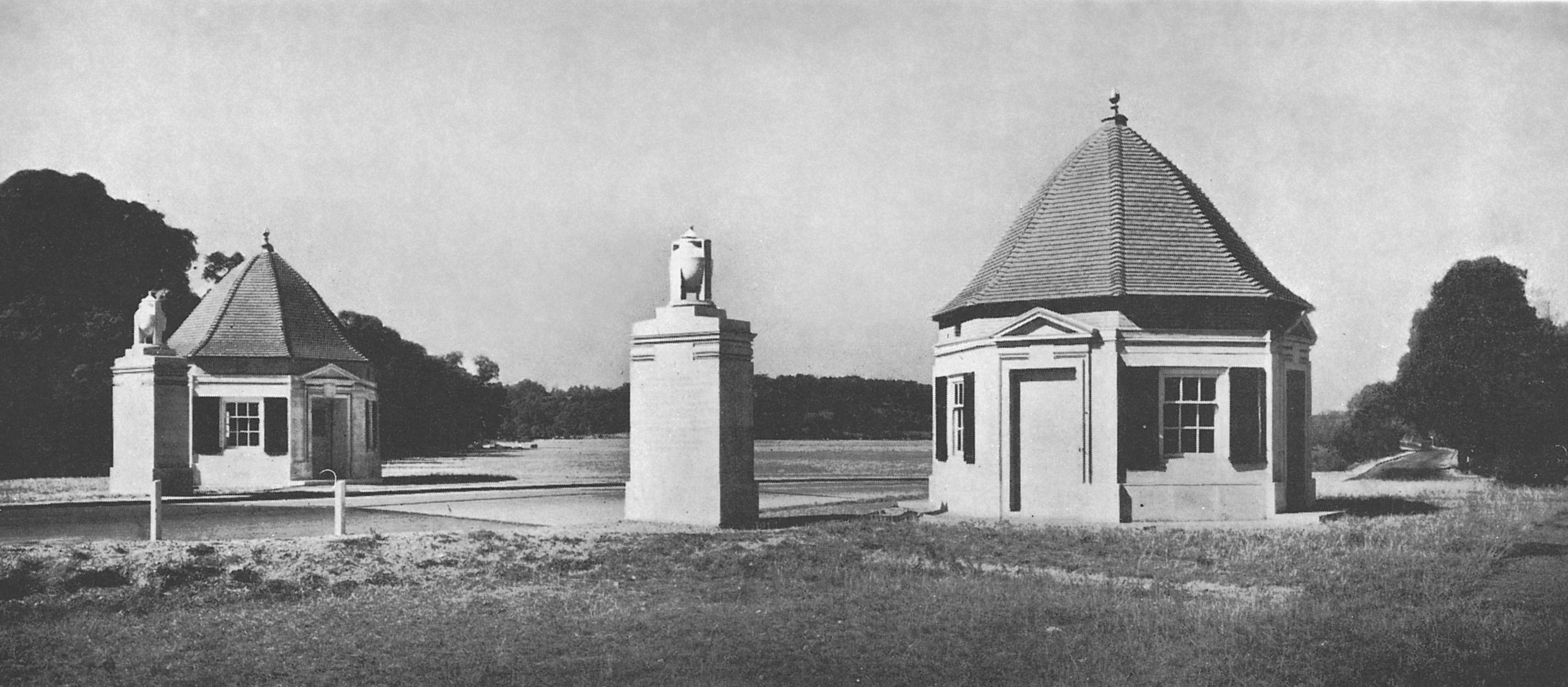

99. RUNNYMEDE SURREY: THE EGHAM LODGES

100. DETAILS OF THE PIERS

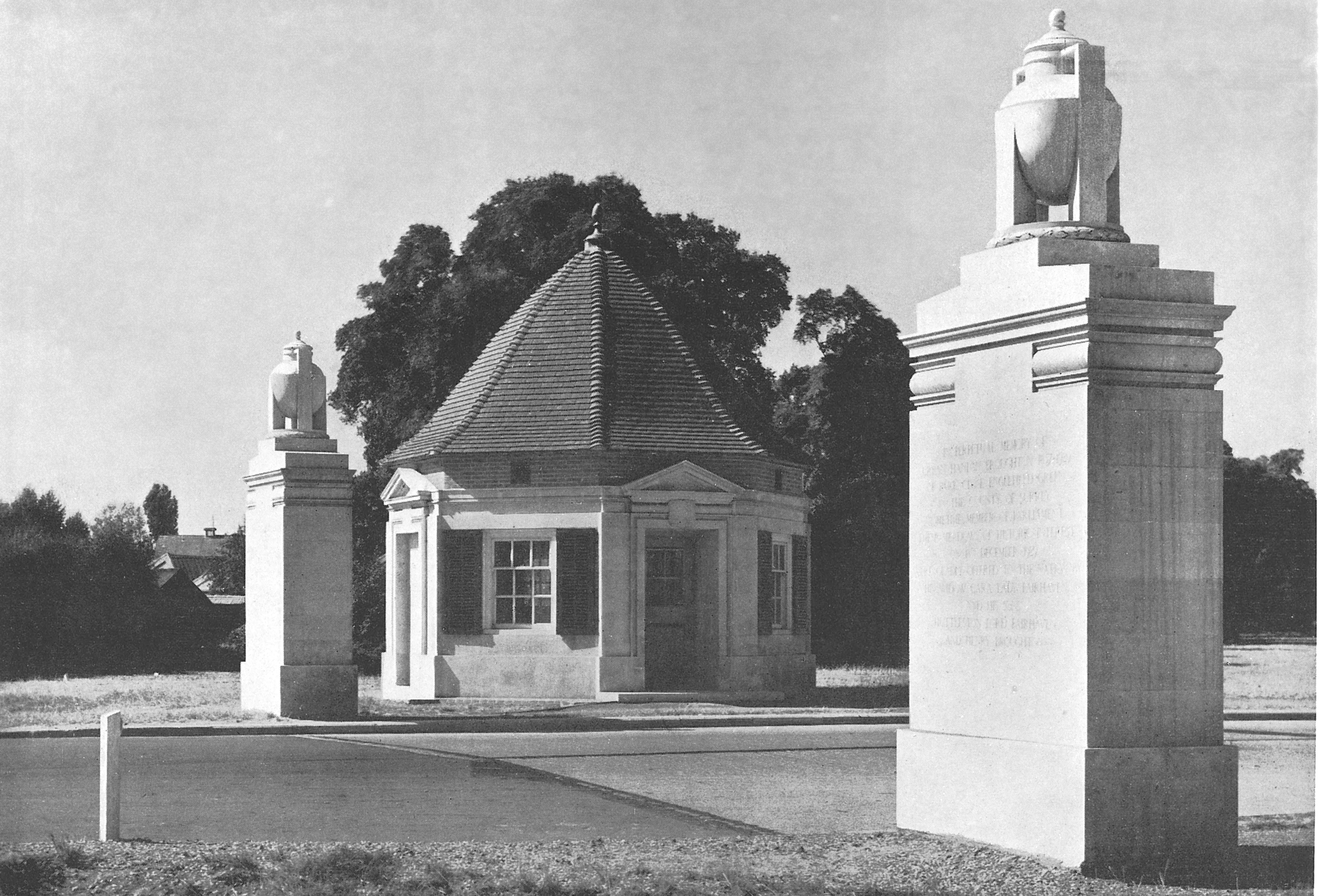

101. RUNNYMEDE: THE WINDSOR ENTRANCE

102. DETAIL OF THE ABOVE

121. NEW DELHI: GOVERNMENT BUILDINGS FROM THE EAST

122. SIR HERBERT BAKER’S NORTH SECRETARIAT

123. APPROACH TO VICEROY’S HOUSE

124. NEW DELHI: GOVERNMENT COURT (Sir Herbert Baker)

125. VICEROY’S COURT

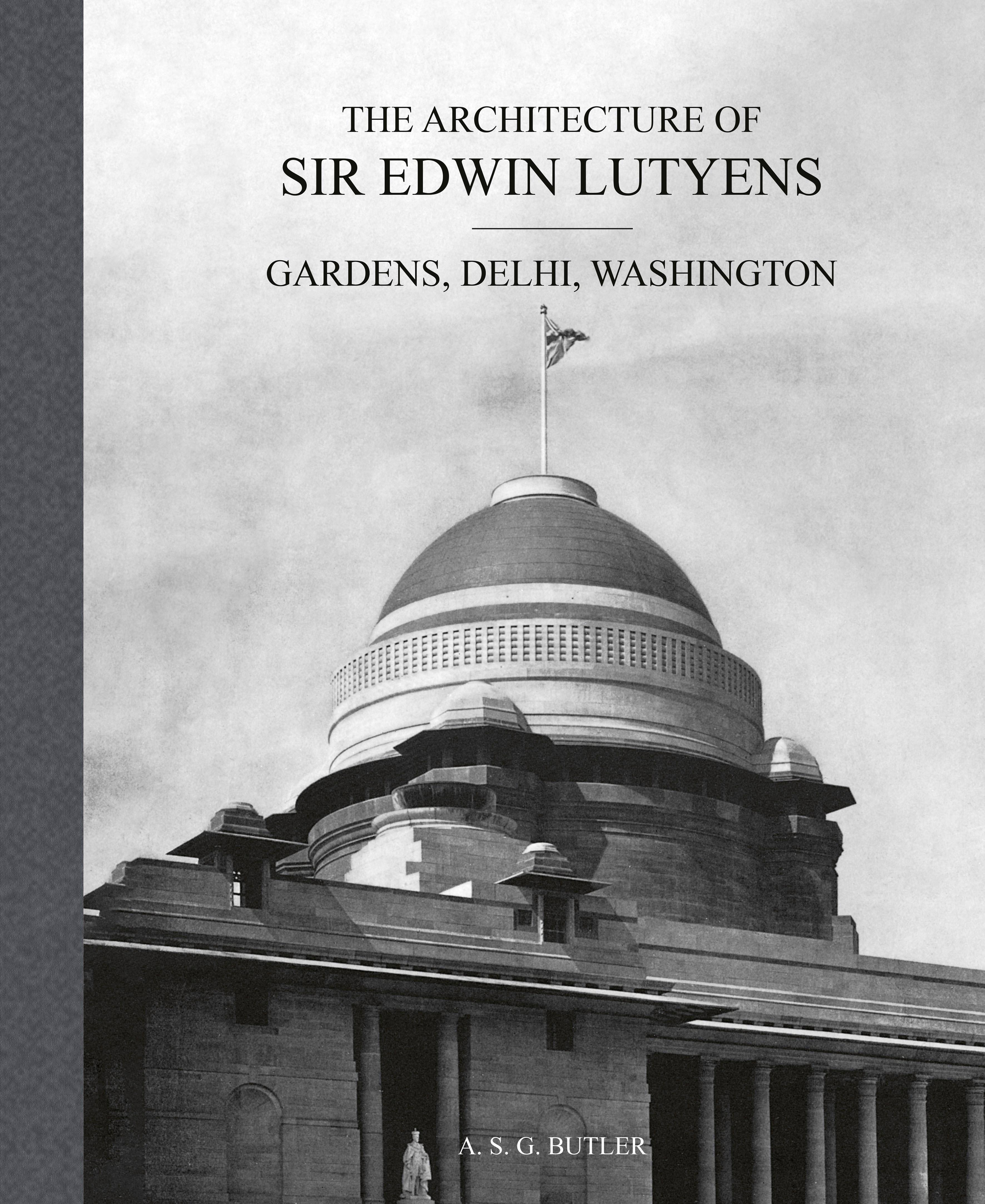

© ACC Art Books Ltd. 2023

All images © Country Life/ Future Publishing Limited, a Future plc group company, UK 2023

World copyright reserved

ISBN: 978-178884-218-1

First published in 1950 by Country Life Ltd., an imprint of Newnes Books © Country Life 1950

Published as a limited edition in 1984 by The Antique Collectors’ Club

This edition published in 2023 by ACC Art Books Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the permission granted to reproduce the copyright material in this book. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions in the text and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

Printed in Italy for ACC Art Books Ltd., Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK www.accartbooks.com