Since Understanding Jewellery was published in 1989, and following the appearance of translations into Italian, Hungarian, Japanese, Russian and, most recently, Chinese, the interest and market for period jewellery among collectors has never stopped expanding. This collecting public is discerning and generally has a thirst for more information about the pieces themselves and the social and historic context of the age when they were produced.

When we began our careers some 50 years ago, period Western jewellery seemed to be of very little interest to buyers outside a very limited group of knowledgeable collectors in Europe and America. These days, the market has evolved so that now Asia accounts for a large and increasing proportion of collectors in this field. These new collectors are almost without exception fascinated by the history, the background and provenance of the jewels they intend to purchase and are quick to acquire the academic skills necessary to making an informed selection. These days we seem to be much in demand for educational programmes in China and Southeast Asia. We find it very satisfying to be teaching a brandnew group of enthusiasts and having the opportunity to share our passion for jewels and gemstones with a new audience fresh to the field. It is also immensely satisfying to see Understanding Jewellery receive the same enthusiastic response in China as it did 35 years ago in the Western world.

It is interesting to note that at the start of our careers Art Deco jewels were just beginning to be collected rather than being broken up so that the metal and gemstones could be repurposed.Today this period is now falling within the widely accepted definition of ‘antique’ – over 100 years old. Even certain jewels from the 1980s and 1990s are now considered ‘collectable’, offering a broad spectrum of styles to be considered by a new generation of collectors. We find it amusing to think that, back in the mid-1980s, we might struggle to figure out whether a particular diamond-set star brooch dating to the 1880s could be considered ‘antique’ or not.

In the meantime, the supply of antique jewels into the market has inevitably dwindled, as so many items now reside in private collections. This has, of course, increased the rarity of those items left in circulation. An interesting phenomenon in recent years has been the renewed interest in natural pearls. These gems, one of nature’s rarities, had in previous centuries been held in the highest esteem, but had lost much of their appeal since the 1920s with the introduction of cultured pearls. They were in a sense ‘rediscovered’ at the beginning of the 21st century and are now of major interest to collectors and professionals alike. Apart from being prized for their inherent beauty, natural pearls have always been considered the queen of gemstones and counted among the most highly prized treasures of noble and royal collections.

Another interesting phenomenon in recent years, which changed attitudes towards acquiring jewellery, is the interest in provenance and celebrity association. One-owner jewellery sales such as those of the Duchess of Windsor and the Princes Thurn und Taxis, which we curated respectively in 1987 and 1992, were instrumental in attracting worldwide publicity for period jewellery. These were followed by a series of jewellery auctions of collections associated with personalities such as Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Elizabeth Taylor. Jewels suddenly returned in fashion and became a respectable area of study. Jewels began to be considered not simply as a form of precious accessory but also, at their best, capable of crossing the boundary between decoration and art.

It has been our ambition throughout our careers to encourage this transition.

The celebrated pearl which was part of Queen Marie Antoinetteʼs personal jewellery collection.

It was sold at auction in 2018 for $36 million, by far the highest sum ever paid for a pearl and exceeding its pre-sale estimate by more than 30 times.

Following the French Revolution (1789–99) and imperialist aggression by Napoleon, the turmoil in Europe brought about a major upheaval in political, social and cultural traditions, and jewellery was to see radical changes as a consequence. The republican ideals of the Revolutionaires in France profoundly influenced society, changing habits, lifestyle, government, religion, and even the calendar. Jewels, considered at this time as a reminder of the Ancien Régime, conflicted with the new ideals and went somewhat out of fashion. An enormous quantity of jewellery left France and was remounted abroad or was sold by its owners for reasons of simple survival. Even the crown jewels were seized. Parisian jewellers, who were the leaders of fashion in Europe, faced great hardship with very little jewellery being produced at this time. Such jewels as were made lack imagination and are of rather poor quality. When the Directorate was established in France on 2 November 1795, there began a slow return to normality with supplies of luxury goods trickling in and the jewellery trade starting to recover.

Dramatic changes in female dress fashion brought in ‘empire line’ dresses inspired by classical antiquity, making corseted dresses with ample skirts redundant. These new, high-waisted, diaphanous garments were unsuited to the size and weight of the large girandole earrings, imposing corsage ornaments and elaborate necklaces that had been fashionable during the Ancien Régime. A new style of jewellery was required, and thus Neoclassical designs quickly emerged across European courts in the last decades of the 18th century, having its apogee at the coronation of Napoleon. The emperor and his wife Joséphine de Beauharnais (1763–1814) were both passionate about jewellery and were instrumental in reviving the industry. Edmé-Marie Foncier (1760–1826) and Marie-Étienne Nitot (1750–1809) were entrusted with the remounting of the French crown jewels in Neoclassical designs that reflected the personal taste of Joséphine: laurel leaf tiaras, combs, hair ornaments and bracelets. In England, a similar passion for jewellery was shared by the Prince Regent – the future George IV (r.1820–30) – who, as a leader of fashion, encouraged the wearing of jewellery at court.

Natural pearl and diamond necklace, c.1805.

This beautiful necklace was made for Joséphine de Beauharnais, wife of Napoleon I, by the French court jeweller MarieÉtienne Nitot – later to become Chaumet. At this time, natural pearls were extremely important as a sign of rank – the bigger and finer, the better. The seven drop-shaped pendants still have great lustre and colour despire their age. The process of stringing pearls was entirely handled by female artisans who worked mainly from their own premises.

OPPOSITE TOP. Diamond jewel, c.1800.

This popular Maltese cross design is set throughout with rose-cut stones in closed mounts. The fashion for pendants in the shape of a Maltese cross was a consequence of the successful British siege of Valletta and the subsequent transfer of the island to become a British protectorate in 1800.

OPPOSITE CENTRE. Diamond jewel, c.1800.

The central hexafoil motif is mounted on a watch spring en tremblant, very much in fashion at this time. The effect in candlelight would have been enchanting as brilliant flashes of coloured light were thrown out by the diamonds, thanks to the spring mounting, all set off by the movements of the wearer. The brooch fitting is a later addition, as the jewel would originally have been sewn directly onto the fabric of the dress. Note the cut of the cushion-shaped diamonds which was a forerunner of the modern brilliant cut.

OPPOSITE BOTTOM. Diamond jewel, late 18th century. Jewels of floral or star-shaped design, similar to this, were very popular throughout the late part of the century and were originally directly stitched to the fabric of the dress. The gold brooch fitting, partly visible on the right-hand side of this example, is most probably a later addition dating to the 19th century. Note the variety and rudimentary cutting of the stones, which may have been removed from earlier jewels and underline the general rarity of diamonds at the time.

LEFT. Diamond cruciform jewel, early 19th century. Crosses in all shapes and forms were a popular design for pendants and brooches at the time. This may well be partly attributable to the high rate of infant mortality. Such jewels very often had concealed, glazed hair compartments in which a lock of the deceased’s hair would have been preserved. The great irregularity in shape, size and cutting is a certain sign of the re-employment of old stones.

RIGHT. Pair of diamond jewels, late 18th century. The six-petalled flowerhead design was popular at this time. The setting is entirely in silver and typically the diamonds are lined with foil. Jewels such as this were made in sets and worn scattered and sewn on the bodice, sleeves and skirt of contemporary dresses.

TOP. Gem-set enamel bracelet, 1830s, formerly in the collection of Theodolinde de Beauharnais, Princess of Leuchtenberg (1814–57).

The subject matter makes this a very unusual example of a bracelet set with Geneva-enamelled plaques. It depicts the 12 signs of the zodiac rather than the more traditional views of the ‘Campagna Romana’ or of Swiss regional canton costumes and landscapes.

BOTTOM. Gold, enamel and turquoise bracelet, c.1830.

The seven painted enamel plaques, probably executed in Geneva, depict local costumes and landscapes of the Lazio region in Italy. The polychrome, richly enamelled acanthus-leaf decoration surrounding the plaques is rather unusual in this context, though the gold beaded work and the choice of gemstones – turquoise and pink foiled quartz – are typical of the period.

ABOVE. Gold, enamel and gem-set bracelet, 1820s. The most popular subject matter for Geneva enamel jewellery is the traditional costumes of the 22 cantons of the Swiss Confederation which had been brought together by the Federal Treaty of 1815. This bracelet was clearly part of a pair, with each bracelet depicting 11 of the 22 cantons. The use of three-coloured gold and of the repoussé technique confirm the dating to the 1820s, although it is possible that these popular designs continued to be produced for the large number of tourists that had begun the Grand Tour. After all, the mounts with the shell motif could have easily been produced in large numbers.

LEFT. Gold and enamel demi-parure, c.1830. Tourist jewellery was at its height in the 19th century and each European country developed local talent. The enamel production in Geneva had flourished by connecting with the local watch industry, and produced very high quality, almost photographic miniatures such as those mounted in this demi-parure, perfectly suited to depicting the spectacular landscapes of the country. The gold frames of this suite, decorated with repoussé foliage and scrolls, may well have been made by artisans from the watchmaking trade.

OPPOSITE. Pearl and diamond corsage ornament, c.1855, formerly in the collection of the Princes von Thurn und Taxis.

This imposing jewel is very similar in design to a series of shoulder brooches created in 1853 by French jeweller François Kramer for Empress Eugénie and very close in style to the sumptuous tiara created by Lemmonier for the marriage of the Empress that same year (see pp.108–109). At the time, only senior members of the European and Russian aristocracy owned or had access to pearls of such large size. Pearls, which were greatly admired, praised and sought-after for their beauty, were also an emblem of wealth, power and status.

TOP. Diamond brooch, c.1840.

The close pavé setting and the archaic cutting of the larger stones is reminiscent of some of the 18th-century imperial jewels from the Romanov family kept in the Kremlin. While this design could have been produced in the workshop of many jewellers throughout Europe, its provenance is connected to the princely Kinsky family based in Bohemia. The sprigs of foliage are indicative of the naturalism of the 1840s.

BOTTOM. Ruby and diamond brooch, mid-19th century, from the collection of Christian Lady Hesketh.

The formal design of this bow brooch is archaic and somewhat unusual for the period because it looks back to the previous century. The punctuation of the edges of the ribbon with small diamonds is also uncommon. The rubies, typically, have been set in yellow gold to enrich their colour.

Revivalism in all its forms, whether archaeological, Renaissance or Egyptian, was at the peak of its fashion between 1860 and 1880, and remained popular throughout Europe until the end of the 19th century and well into the 20th century. In fact, some of the most distinctive creations of Jules Wièse date to the 1890s (see below). The Giuliano shop in Piccadilly, London, closed in 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, while the Castellanis continued producing and retailing their archaeological jewels in Piazza Fontana di Trevi, Rome, until 1930.

ABOVE. Gold and ruby brooch by Jules Wièse, Paris, c.1890. This is a good example of the distinctive revivalist work of Wièse, which was often inspired by Anglo-Saxon, Merovingian and Frankish jewels from the early Middle Ages. The jeweller has made a special effort to give this jewel an ancient appearance by using high-carat gold and treating its surface with mercury oxide to imitate the reddish patina imparted by a long burial in the ground. As was customary for jewellers working in the revival of ancient styles, this brooch is clearly engraved with the signature of Wièse and stamped with the maker’s mark, to make sure the jewel could not be mistaken for a fake ‘antique’ jewel.

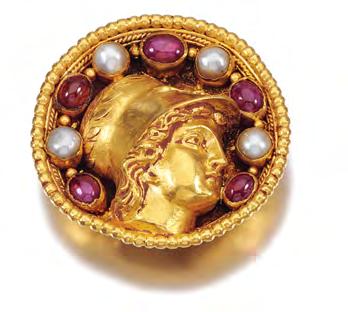

RIGHT. Gold, natural-pearl and ruby brooch by Jules Wièse, Paris, c.1890. Another example of Wièse’s work in the archaeological revival style. Here, the subject matter has been taken from the Greek classical world. While corded wire and beaded work were widely used in Greek and Etruscan jewels, the inclusion of gemstones of substantial size in the design – unusual in classical jewels – makes this piece more of a 19th-century pastiche than a reproduction.

Star ruby, enamel, diamond and seed-pearl pendent necklace, probably English, 1880s. Although unsigned, this pendant is very much in the style of the Giuliano family but is probably the work of Ernesto Rinzi, a jeweller of Italian origin working in London, renowned for his jewels in the Neo-Renaissance taste and the high quality of his enamelling. Here, however, the black-and-white piqué enamel is more inspired by the 17th century. The star ruby was definitely chosen for its interesting purplish-red shade and for the asterism effect, rather than for its intrinsic value.

ABOVE. Diamond necklace, 1880. A rather sumptuous jewel from the collection of Flora Sassoon (1859–1936), a prominent society figure, philanthropist, businesswoman and scholar in Bombay and later London. The opulent display of fine cushion-cut diamonds is very much in step with the fashion of the 1880s, when society required and expected ladies to wear extravagant jewels at court as well as at dinners, balls and other formal occasions. Jewels were essential to complement the elaborate and intricately embroidered evening gowns of the time, and their generous décolleté provided ample space for substantial fringe necklaces such as this example.

OPPOSITE. Sapphire and diamond necklace, probably German, late 19th century. The swags of ribbons and garlands, coupled with the use of knife-wire to connect the sapphire drops to this sumptuous necklace, points to a date close to 1900. The formality and perfect symmetry of the design is very much in the taste of German and Austrian creations of the closing years of the century.

ABOVE. Emerald and diamond necklace, Italian, c.1880, from the collection of the Princes Doria-Pamphilj.

The necklace is designed to display the five beautifully matched, fine Colombian emeralds ranging in size between 13 and 16 carats. As often happens to jewels, this necklace was at some stage lengthened by the addition of eight collet-set diamonds taken from an earlier rivière. Although the design is in line with that of contemporary French jewels and the gemstones are of a high standard, the workmanship does not match the refined quality of Parisian work.

RIGHT. Pair of emerald and diamond earrings, from a Spanish ducal family, c.1880.

It is fortunate that this fine pair of Colombian emeralds have survived in their original mounts because stones of such quality were often repurposed and reset in more modern mounts. The fittings have also been spared alterations and retain the characteristic form typical of the Iberian Peninsula: large, hinged loops which attach to the top of the mount, as can be seen in the photograph.

Emerald and diamond necklace, c.1900, from a European noble collection. An interesting early use of cabochon gemstones in a European jewel dating from the turn of the century. It is possible that the emerald cabochons were actually cut from the emerald beads of a traditional Indian jewel and that the emerald drops were originally suspended from a necklace of the same provenance.