So who was speaking? Nobody, I was imagining things. Back to the picture. I looked hard at that extraordinary blue above the tops of the trees, like a magic light-darkness, dark-lightness, a blue that seemed to be burning like fire would if fire was blue.

Fire is blue, the voice said. Just look properly the next time you see a flame.

Now whoever was speaking, it was a woman’s voice, was laughing.

For God sake Alison, she said, do you go near a cooker so rarely these days that you’ve forgotten there’s such a thing as a gas flame? That’s blue flame. Pretty contentious, that blue flame right now, a little symbol of the ruination of climate and the routing of nature and the fragmentation of international order because of all the powergames round power.

Only my mother ever used my full name.

Dear God, it sounded like my mother’s voice. She’s been dead for three decades.

Uh oh.

I made myself think instead about something else, uh, what? Spruce. Let’s take the word spruce. It’s both a strange and a fitting word for

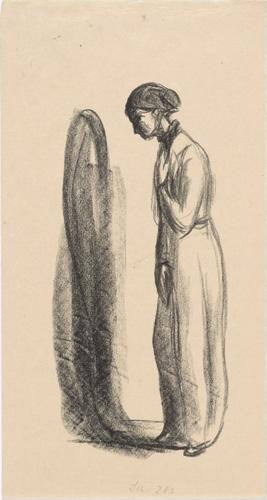

Separation, 1894

from The Comedy of Love, my poem shall be lived beneath spruce and shadbush, and a wellknown line from a century-old poem by Nils Collett Vogt. Var jeg blot en gran i skogen. Oh, to be a spruce in the wood.

So notions of spruce, or gran, could veer from hellish dark and heavy and germinal all the way to bones formed in the ocean, the ever-changing possibilities for growth on the human face, and a good place for the germination of poetry.

I looked at the picture again.

It’s like the tree on the right is gesturing to the progress of the littler trees at the core of the picture, encouraging them with the wave of a branch, go on, on you go.

Gran is also what my brothers’ and sisters’ kids all called our mother, their grandmother.

That’s the thing about Munch and his trees, the voice that sounded so like my mother’s voice, still behind me, said.

Then the voice from nowhere carried on talking about Munch, like my mother of all people knew about Munch, like she knew I was looking at a picture right now, like she knew about

the power crisis and the international unrest and the climate ruination in a world she’d left thirty years ago. Like she knew it all. It was lovely to hear her voice again. That long tapering branch in the version of Separation he painted in 1894, the voice was saying as I thought this (I didn’t dare turn round, what if she was there – no, what if she wasn’t) –and the painting so dilapidated because he liked to let his paintings get weathered, she went on. That branch reaching as if longing to touch the woman the man’s leaving, and her strand of hair blowing out under it, parallel with it. I mean, that branch, it’s a figuration of pure longing. Look at the little moments of red on it, are they leaves or blooms or fruit? And how the man himself, in turning away, seems to be merging with the plantlife. Even the stone’s hard mass is alive. That’s not just a sentence I’m saying, Alison. That’s the title of a picture by him. 1930. Look it up. Go on.

I sat as still as a stone.

Come on, she said. Get going, go on. Get to the heart of it. It’s urgent. It means the world.

Even the Stone’s Hard Mass is Alive, c. 1930

Worlds are Within Us, 1894

I did as she said. I typed it into the computer document I had of some of Munch’s pictures, even the stone’s hard mass is alive 1930.

Up came a drawing of a rockface or a stone that’s literally opening, like it’s a box with a lid – like landscape is a container. A head has appeared under the lid. The head looks out, indifferent, above an open road.

Does the head have a body? It’s impossible to tell. Does this person whose head it is live in the stone? Are they trapped in the stone? Calcified? Ossified? Petrified? Have they been swallowed by rock, subsumed by landscape? Are they trying to get out of the stone? Is it a picture of someone pushing their way out of stone as if out of a box, refusing to be boxed in? Or are they naturally a part of the stone they’re in, and happily at home in it? They look quite calm.

Is this what it means to be in the world? Living between fixity and vitality, negotiating between interior and exterior?

On my screen there’s also another much earlier version of this exact same image, a charcoal drawing Munch made three decades before, called Worlds are Within Us (1894). It shows a

Beach, 1904

human head emerging under the lid of a stone too, above a road that curves off and away. This person looks more jaded, more dark-eyed.

See? my mother’s voice said behind me.

Yeah, but what exactly am I looking at? I said.

Well, isn’t that the question? she said. To paraphrase Hamlet. Now, go and find the painting he did called Beach (1904), where all the rocks and pebbles on a shore in all their different shapes and colours are leaning towards and away from each other like they’re moving, magnetised towards each other, because I bet you can’t look at it now without having to consider that every single one of those stones might have someone inside them. Ha! And after that, I reckon it won’t just be that every stone you see in a painting or any kind of work by Munch has a possible life in it. It’s more that it’ll be impossible for you not to think of the possibility of a self in every real stone you ever see. It’ll be impossible for you to treat stone, rock, landscape, what’s simply there under your feet, with indifference. It’ll be impossible for something not to unfix and open itself in you.

Children in the Forest, 1901–02

Death and Spring, 1893

Or would she be taking the shape of her charming-stern / stern-charming young self, dripping in children and all of them good as gold because she knew how to bring up a big family well even though she was so young and there was so little money?

Would she be her middle aged self, ill and thin and bewildered and gentled, heart sorry to be leaving the world so early?

She didn’t sound in the least bewildered. She sounded strong as a mountain.

She’d be bones now. Fishbone. The dead. How hopeless to gather what in life’s been torn to bits. Like you’d try to put together a shattered glass. That’s Munch himself speaking, not out loud in my room thank God, no, safely contained in his notebooks; listen, there’s only so many ghosts a person can cope with. Maybe in Norway people can cope with nineteen where someone in the UK like me (even though I’m Scottish and we’re also meant to be pretty haunted) can only really cope with one. Nineteen different kinds in the room. Now that’s what I call a versatile people. I remembered a work by Munch, a drawing, where it’s as

The Insane, 1908–09

can see moving in a breeze. Yes, more air. But myself I think what that girl’s looking at is the place right next to her nose and mouth, the place where breath happens, the space that’s air. Munch always scrubs it clear, clean, a mist dissolving, an air-halo, like a holy thing happening. The need for it, the struggle for it, the sacredness of it. As if he’s gifting that sick child that air she needs as we watch.

In the empty room with my dead mother I remembered now how her own sister had died of tuberculosis in Ireland in the 1930s. A painter who knew air, she said. Yes, I said. Trees. What about them? she said. They’re one of his best ways of making air visible. The Storm (1893). Look at the wind in the trees. And how the light from the house behind them coming through the branches looks like there’s a fanned fire at the heart of the trees. And how all the people are holding their hats on. Or is it their ears they’re holding, against the scream of the wind?

Now you’re talking, my dead mother said. Yeah, I said, but why do you reckon all the

30

The Scream, 1910?

The Magic Forest, 1919–25

Towards the Forest I, 1897

of how that tree conducts the world, conducts the sky like the sky’s its orchestra. Chestra, the voice said.

And what about all those paintings of the girls, the people, on the bridge, I said. They’re not really about the people at all. They’re really all about what it means for a huge tree to have a huge reflection, regardless of the people who use the bridge or why they do and regardless of how long or how short a time someone stops and leans over its railing there it is, the mass force of the tree and its image in a shifted element. And, yeah, in that painting called The Dance on the Shore it’s like the trees are embracing the young and containing, protecting and holding the old, and all together on the bright flow of light that’s the sand beneath the dance. And the dark of the woods, like the forest is the threshold of everything, and the way the children in his paintings of the forest pause before the woods like they’re pausing before a story. Or the way the mother and the child have become transparent, you can see right through them, as they approach The Magic Forest (1919–25), and how the couple in some of the versions of Towards

The Yellow Log, 1912