Archaelogical Sites and Cities / Principal Kilns

Autonomous Regions

Provinces Municipalitoes

Special Administrative Regions

Archaeological Sites and Cities (5000 BCE – 220 CE)

Hangzhou

Erlitou

Anyang

Guanghan (Sanxindui)

Zhengzhou

Houma

Chang’an

Luoyang

Xian

Changsha Present Main Cities

Beijing

Tianjin

Shenyang

Shanghai

Hong Kong

Guangzhou (Canton) Principal Kilns (10 th – 13t h Centuries)

Xingzhou, Hebei Province (xing ware)

Quyang, Hebei Province (ding ware)

Cizhou, Hebei Province

Yaozhou, Shaanxi Province

Kaifeng, Henan Province (Northern guan ware)

Yuxian, Henan Province (jun ware)

Baofeng, Henan Province (ru ware)

Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, (qingbai ware)

Jizhou, Jiangxi Province

Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province (Souther n guan and ge ware)

Longquan, Zhejiang Province

Dehua, Fujian Province

XINJIANG TIBET

Chinese miniatures are autonomous, threedimensional, man-made objects, of a ‘handy’ size – that is, no larger than ten centimetres –which are a deliberately reduced version of the same object in actual size. So, something very different from what in the West is understood by miniatures: painted or drawn illustrations in old, mostly religious, manuscripts or small portraits.

What makes these Chinese miniatures, of which the oldest copies of jade are more than 7,000 years old, so special? First, in the long run they were made of almost every material you can think of, such as bronze, ivory and gold, but also of more ordinary materials, like ceramics and wood. Second, they could portray almost everything, such as gods, people, animals, buildings, vehicles, utensils and so forth. Third, they give us a glimpse into the lives of very ordinary people, and these miniatures, above all, made it possible to portray all kinds of intimate, even erotic, and humorous subjects that do not occur in official visual arts or literature. And finally, the phenomenon of miniatures is still virtually unknown, even in present-day China, as is evident from the fact that there is hardly any literature on this subject. That is all the more remarkable when one realises how much has been written about the much younger Japanese netsuke.

It may all sound very logical and simple now, but what was needed to find out?

On the trail of a new phenomenon

In June 2008, as director of the European Ceramic Work Centre (EKWC) in ’s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands, I gave a lecture about this centre in Fuping, in the Chinese province of Shaanxi, at the invitation of the International Ceramic Art Museum there. On that occasion, I also visited the Yaozhou Ceramics Kiln Museum in Huangpu,

Tongchuan City. During the viewing of the permanent exhibition of ceramics, I noticed three strikingly small figures, quite similar to the miniature official shown here (FIG. 1). The objects were arranged together in a separate showcase. They struck me because such figurines are usually exhibited together with larger ones and therefore attract less attention. A sign stated that these were figurines representing an official, a monk and a girl. All three, made from green glazed (celadon) stoneware, were attributed to the Yaozhou pottery centre and dated to the Northern Song period (960–1127).1 It was not stated what the function of these figurines was at the time, or what significance they had.

At that moment, I didn’t think about it any further. Yet in the years that followed, I became increasingly aware of the existence of such small objects. I also noticed the great diversity in what they depict. This raised the suspicion that it could be a specific category of objects, namely miniatures, in Mandarin Chinese zaoqi zonguo de suoying

The question as to which properties define this category and what the functions of these miniatures were arose again in the spring of 2013 at the reopening of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. In the new Asian pavilion, art objects from China, Japan, Indonesia, India, Vietnam and Thailand are displayed. The majority of them belong to the extensive collection of the Royal Asian Art Society in the Netherlands, founded in 1918, which was given on permanent loan to the museum. At the time, an important part of the semi-permanent exhibition in this pavilion was a group of ten gilt-bronze miniatures, exhibited in a separate wall showcase (FIG. 3). This showed the earliest development of Chinese, especially Buddhist, sculpture and acted as a prelude to what is presented as the highlight of the collection: the monumental Guanyin sculpture, dated c. 110 0–1200, of polychromed and gilt wood (FIG. 2 ). This new confrontation with the phenomenon of early Chinese miniatures further aroused my interest and led me to devote a scientific study to the subject.

Research questions

At the heart of the research was the question: what is a miniature, or, to put it differently, how can the term ‘miniature’ be defined? To answer this key question properly, it was necessary to ask other, more specific, questions like: what was the function of early Chinese miniatures, which materials and techniques were used, how were production and sales organised, which representations occur and what do they mean? Just as relevant were questions such as: how did the practice of collecting develop, and are similarities to be found between miniatures in China and abroad? All these questions are answered in the following chapters.

State of science

Virtually no scientific research had been done into early Chinese miniatures.2 However, a few small steps in that direction had been taken in the past. Two articles from the 1950s refer to ‘Chinese miniatures’ but mainly in the sense of small objects that lend themselves

well to the creation of a collection. At the time, there had as yet been no definition of the term ‘miniature’.3

In her article on Chinese miniatures in bronze, Lady Ingram suggests the possibility that these are toys for children or models for craftsmen, or that they were made because the craftsmen simply enjoyed making them.4 After describing about twenty bronze miniatures, she concludes her story with an explanation of why these miniatures are so popular with collectors: they are representative of the shapes and the quality of Chinese bronzes throughout the centuries and do not occupy much space.5

The London-based art dealer Edgar Bluett, who specialised in Eastern art, illustrates this ‘collectability’ with his article on the collection of the married couple F. Brodie Lodge. Among other things, he describes the contents of a wall cupboard: around one hundred Chinese antiques from the fourth to the eighteenth centuries, consisting of miniatures of earthenware, porcelain and bronze.6 He does not discuss the function of these miniatures. A closer examination of the accompanying, not very sharp, black-and-white photo of this wall cabinet shows that, of the ninety-eight ceramic objects arranged therein, about twenty

Musical instruments: ceremony, vigilance and relaxation

Bells are among the oldest known Chinese musical instruments.78 Trapezoidal specimens, cast in bronze, were already in vogue in large and small format during the Shang period and remained popular up to and including the Zhou period.79 The type without a clapper, which makes a sound by hitting it with a hammer or stick, is called nao. Series of decreasing size and corresponding sound were played in orchestras (FIG. 32 ). The type with a clapper is called zhong. This type dates from the late Western Zhou period but was also used for a long time thereafter. These bells usually show a linear ornament, occasionally combined with the stylised head of a monster, called taotie. Both types of bells had a thick wall and were played as a musical instrument.80

Small bells, called ling, have a round shape and, like the larger bells, are of the zhong type, equipped with a clapper. The oldest date from the Shang period, but most, especially the smaller formats, date from the Warring States and the subsequent Qin and Han periods. These round bells, but also the miniature version of trapezoidal zhong, were used for the harness of horses and for the collars of dogs or attached to a pennant or bier (FIG. 30 ). Most of the specimens had a ceremonial or signalling function. To make them as light as possible, the ling and the zhong have a thin wall, which is decorated with lines and dots in relief. All types, both large and small, also come in ceramic. In that case they were burial gifts.

The whistles, with a few exceptions made of ceramic, are of a different order.81 The function does not turn them into miniatures. After all, they are fullsize. That they are treated here as such is because they almost always have a figurative form in miniature format. Although a signalling and a luring function cannot be excluded, it can be assumed that most have served as, not too expensive, toys for children. In the case of a signalling function, one should think of a shepherd who, with his whistle, called the herd or his dog to order and, in the case of a baiting function, of a bird catcher.82 Whistles come in many shapes and sizes, but they are always recognisable by the two holes, for blowing in air and for the air outlet respectively. They usually represent a deity, human being, flower, fruit or animal. For obvious reasons, the shape often concerns a songbird. A single early specimen dates from the Han period, but most are from the Tang and subsequent periods. A strikingly large number of realistic bird whistles are from Changsha in Hunan Province (FIG. 31). The whistles of sancai The specimens in the form of the head of a western ‘barbarian’, that is the kind of people who traded with

Remarkably realistic were the bronzes that were cast in the Dali kingdom. This kingdom, inhabited by the Bai people, was located on the southern border of the empire, in the area of today’s Yunnan Province. The bronze figures portrayed people and sometimes entire scenes that seem to have been derived from everyday life, such as a dancing shaman, men leading an ox, or the execution of prisoners of war. However, most of these groups were used to decorate the lids of ceremonial vessels and therefore cannot be counted as miniatures. During the Six Dynasties period, most types of bronze miniatures from the previous periods were retained. The Buddhist figures which are a miniature version of the larger variants were new. The earliest specimens from the third and fourth centuries (FIG. 67) still show clear influences of the stone sculptures from Gandhara and Kashmir, especially in the hairstyle and clothing. From the Northern Wei period on, these style influences were replaced by a more Chinese, initially linear style. Only after the middle of the sixth century was this style in turn repressed by a three-dimensional realistic style.

Far rarer than these Buddhist miniatures is the Daoist miniature, which in all likelihood represents Laozi (FIG. 69) . 187 Equally special are two shrines of gilt bronze (FIG. 68 ) that were cast after the example of similar specimens of stone and ivory from Gandhara.

Jin period of green glazed stoneware carries a Buddhist lion in his lap that is so small that the name lap dog is in its place here (FIG. 117).266

Guardian gods are recognisable by their often muscular bodies, cruelly grinning heads with awesome canines, and exuberant, ‘barbaric’ jewellery. Jambala and Mahakala, among others, enjoyed great popularity in the west and south of China and especially in Tibet.267 They had to protect Buddhist believers against all kinds of catastrophes and therefore they are well represented among the miniatures. It is remarkable that a relatively large number of glazed stoneware whistles from the Song and Jin period portray these guardian gods (FIG. 116).268

In China, Laozi is regarded as the founder of Daoism and author of the Tao Te Ching (Book of the Way and the Virtue) (FIG. 69).269 Born in the state of Chu, he is said to have lived between 604 and 507 BCE, during what is called the Spring and Autumn period.270 This philosophy is based on a cyclical course of events and on the harmony of opposing

forces. Early images of Daoist figures are much less rich in number than the Buddhist ones. Nevertheless, a number of representations of Laozi and other Daoist deities have been preserved, both in large format and in miniature.

Although Hinduism never took root in China, certain gods from the Hindu pantheon were, through Buddhism, incorporated into Chinese mythology. One example is the god Ganesha portrayed in a gilt-bronze miniature from the Tang period (FIG. 118 ). He has the body of a young man and the head of an elephant and is the god of knowledge and wisdom; he removes obstacles and therefore acts as the patron god of travellers. Despite his Hindu origins, his portrayals were found several times in the hidden repositories of Buddhist temples and tombs from the Tang period. The same applies to Garuda, a mythical creature, half-human and half-eagle, who serves as a riding animal of the Hindu god Vishnu.

Earth spirits (zhen mu sho) have belonged to the permanent repertoire of grave figures since the Northern Wei period, but especially so during the Tang period (FIG. 120 ).271 Most of the time they were hybrid fearsome figures, composed of parts of different animals, who had to save the deceased from all kinds of disasters. In that sense they had the same function as guardian gods.

According to tradition, Liu Hai was a Daoist alchemist from the Quanzhang School. Together with his teachers Lü Dongbin and Zhongli Quan, he was counted among the Eight Immortals from the tenth century on. So far, no early miniatures are known that portray Liu Hai himself. His attribute is a cord with coins, with which he manages to lure his permanent companion, the Three-Legged Toad, out of his den. Because of these associations, he is revered by many as the god of wealth. Also Daoist in origin, and popular from the Yuan per iod onwards, are the Heavenly Twins (He he erxian), represented here by a miniature of qingbai porcelain from the Yuan period (FIG. 119). Depicted with a vase or box and a lotus flower, they symbolise the wish for harmony, wealth, peace and a happy marriage.

In the Song and subsequent Jin and Yuan periods, the figure of Mo he le, or Mo hou lo, was popular.272 He is depicted as a man holding a baby on his lap with both hands (FIG. 121). In Central China, in particular in the province of Hubei, his portrait served as a suitable gift to wish a woman the birth of a son during the Feast of the Loved Ones (qixi), on the seventh day of the seventh month. The Divine Farmer (Shen nong) is seen as the inventor of agriculture. 273 He taught mankind how to plough, the benefits of

not apply to the Chinese toggle. This is all the more remarkable because the use of the Japanese netsuke, according to the current literature on this subject, did not become fashionable until the seventeenth century, during the Edo period.374 It seems that what applies to most Japanese (applied) arts also applies to the netsuke, namely that it is inspired by much older Chinese examples. The explanation for the lack of much literature about Chinese toggles could be that the early specimens were not recognised as such and that the later specimens rarely exceeded the level of folk art. Apparently they were not considered worth the effort of a serious art-historical investigation.

Luxury items: small is beautiful

The expression ‘small is beautiful’ applies to many miniatures but in particular to the numerous boxes and small containers with lids that have been preserved, such as a toilette box (FIG. 196). The round box is made of pure white porcelain that is covered with light blue (qingbai) glaze. This porcelain is typical of the ceramics produced in the Song period

by the many kilns located in Jingdezhen in Jiangxi Province. The box has a flattened round shape with a ribbed wall. The lid shows a relief decoration of a peony, and the base is flat and unglazed. The glazed inside of the box shows a lotus. Between the stems of the plant and around the not yet opened lotus bud, three dishes open for storing make-up. The peony (mudan) is the symbol of prosperity and honor but also of femininity, love and affection, while the lotus, rising from the muddy water, stands for the Buddhist faith (FIG. 6). The lotus flower itself (lianhua) and also the lotus seed pod symbolise the desire to have children. The meaning of this shape and decoration made the box a perfect wedding gift.

The relief decoration on the lid of a second qingbai box shows a boy walking with a fishing rod over his shoulder from which a fish he has just caught dangles ( FIG. 124 ). Although the symbolism is more hidden here than in the previous box, it seems that this is also a wedding gift. Because the fish lays many eggs, often swims in pairs and thrives in its own element of water, the animal symbolises a happy marriage, having many children and, more generally, abundance – the latter because the word for fish is homonymous with the word for wealth (yü). The depiction of both the boy and the fish implies the wish for rich offspring. Both men and women used these boxes for storing and carrying make-up items, such as kohl, dyes and perfumes, but also for medicines, incense, seal paste, salt and herbs. Tubular boxes were used for storing needles. That so many have been preserved is because they were often given to the deceased in his or her grave as personal property (renqi), used during their life and worn on the body. In this case, they are usually found during excavations on or in the immediate vicinity of the remains. Jade and bronze specimens, just like the later specimens of gold, silver and other precious materials, had a better chance of survival than the simpler ones of ceramics or wood, not only because of the durability of these materials but also because of their preciousness. For this reason they were handled with more care. What makes these boxes and tubular containers so special is that their small size offered the maker every opportunity to indulge in the use of materials and the applied decoration.

The oldest preserved boxes of ceramic and bronze date from the Shang and the Zhou periods. In a bronze box from the early Spring and Autumn period, shaped as a taotie mask, the eyes on either side were used not only to attach the lid but also to carry the box on a cord around the neck. Bronze and gold inlaid specimens date from the Eastern Zhou period. Boxes of jade are much rarer; the earliest is from the

Han period (FIG. 197). Hereafter the use of other materials also increased, given the countless burial finds of boxes made of gold (FIG. 198 ) and silver (FIG. 75). That these precious metals were used is explained by the more frequent contact with the neighbouring nomadic peoples, who traditionally loved them .375

The fact that boxes of painted lacquerware from the Warring States and the Han periods (FIG. 28 ) also were excavated is remarkable, given the transience of the material. Both a dry climate and the careful way in which high-ranking people were buried have made that possible. Boxes of lacquerware, with so many layers superimposed on each other that a decoration could be carved in deep relief, date from the Yuan period and afterwards. The same applies to the specimens made from enamel cloisonné; the technique was introduced by craftsmen from Central Asia to China in the Yuan period as well.

Despite the great variety in the materials used, the majority of the preserved boxes are made of ceramic. They were made by almost all pottery centres. The boxes with a sancai lead glaze are colourful, attractive and therefore much sought-after by collectors (FIG. 29).376 Together with the boxes of qingbai porcelain and the slightly later blue-andwhite decorated porcelain boxes from the Yuan and early Ming periods, they are the highlights in an impressive series.

There are three other aspects that deserve some attention here. The first aspect concerns the influence that luxury articles such as glass, brocade silk, gold and silversmith’s wares, imported via the Silk Roads, exerted on Chinese crafts. The imitation concerned both the form and the decoration. An example is a golden bottle imported from Central Asia from the Northern Wei period (FIG. 198 ) with a Chinese imitation of it in glazed earthenware ( FIG. 199) from the Sui or early Tang period. A fragment of brocade silk, attributed to Sogdia and dated to the eighth century, offers a second example (FIG. 200 ). The animal figures, be they stags, eagles, griffins or mandarin ducks, and the striking pearl border were eagerly imitated by the potters who produced the multicoloured sancai pottery in North-West China during the Tang period (FIG. 157). This trend proves how much the Chinese empire, under the rule of the Tang, was open to foreign influences.

The second aspect is about whether miniature crockery from the Song period and beyond involved counterfeiting antiques or an archaic style. Although the true heyday of bronze culture had already passed by a thousand years, a modest subsequent flourishing

China and the world in miniature

The oldest Chinese miniatures that are known date from the fifth millennium before our era, a period from late prehistoric times, which is called the Neolithic in both the East and the West.458 Just like elsewhere, these miniatures functioned initially as a fetish and later as a sign of distinction. After this period, when historiography started to happen worldwide, the diversity in the functions that the miniature held in China gradually increased. The production of Chinese miniatures fits in with a worldwide phenomenon. Moreover, because goods and ideas were continually exchanged through trade contacts and expeditions, there is talk of globalisation. After all, it is more than likely that incidental contacts with neighbouring cultures and countries occurred, directly or at least indirectly, at a very early stage, that is to say in prehistory or what is called the archaic period in China.

However, the first structural land-based contacts between the East, Europe and India, in the sense of both organised and regular, took place in the Western Han period, when the various Silk Roads were used by numerous caravans, mainly driven by Central Asians. At the same time, maritime trade with South-East Asia and India began and later also with the Middle East. This flow, not only of merchandise but of all kinds of economic, religious and cultural influences, has continued back and forth to this day.459

This fact made it interesting to examine the relationship between the development of miniatures outside and within China. For practical reasons, this research is limited to cultures outside of China that are known or believed to have been directly or indirectly influential or to have been influenced themselves. This includes the development of small sculpture because it played an intermediary role in a number of cases. There wasn’t only regular mutual influence; the various functions occasionally also show remarkable similarities. To further substantiate this perspective, this comparison has been extended to our own time.

Prehistoric miniatures

The oldest miniatures date from the Old Stone Age (2.5 million–10,000 BCE).460 The oldest three-dimensional representations of a human concern a woman. They are known as ‘Venuses’. In these sculptures the emphasis is on the reproductive organs. These are not only highly articulated but also often magnified, while the head, hands and feet are missing or are shown rudimentarily. The usual view is that these statuettes of supposedly pregnant women have to do with a fertility cult. The oldest is the Hohle Fels Venus, six centimetres high and carved from the tooth of a mammoth, which was discovered in 2008 in a cave near Schelklingen in Baden-Württemberg, in southern Germany.461 The statue is dated to the Old Stone Age, between 38,000 and 33,000 BCE. However, by far

the best known example is the Willendorf Venus, which was found in 1908 by the archaeologist Josef Szombathy near Willendorf in der Wachau, Austria (FIG. 242 ). The 11.1 centimetre high statue of a pregnant woman, carved from limestone and coloured with red ochre, is dated between 24,000 and 22,000 BCE.462 Other ‘Venuses’ found in Europe are the Brassempouy Venus, located in the department of Aquitaine, Landes in the South of France, of which only the 3.65 centimetre high head has been preserved,463 and the 14.7 centimetre high Lespugue Venus, which was found in the promontory of the French Pyrenees.464 Both are carved from mammoth tooth and are dated between 26,000–20,000 BCE and around 25,000 BCE respectively.

In addition to these Venus figures, sculptures of animals have also been found, such as the Cave Lion from Isturitz, carved from reindeer horn and found in a cave near Isturitz in the French Pyrenees.465 It is dated to the Old Stone Age, between 20,000 and 15,000 BCE. From the scratched arrows and the bore holes in the lion’s body, it is concluded that this is an imitation with which a hunter wanted to exorcise his prey. An early example of the combination of a human and an animal is the Lion Man, also carved from mammoth ivory, found in the HohlensteinStadel cave in the German Swabian Alps (FIG. 243). The 31.1 centimetre high sculpture represents a man with the head of a lion. It is dated to the Old Stone Age around 38,000 BCE and is considered the oldest human-animal figure in the world. Other prehistoric sculptures from the Late Stone Age, mostly found in southern French caves, cut from mammoth ivory or reindeer horn, represent bison and mammoths, among other animals.

The early art from Mesopotamia, the area between the Euphrates and the Tigris, has also yielded a wealth of miniatures,466 the oldest of which date from the proto-literary period, which was dominated by the city of Uruk. The most famous miniature is the Guennol Lioness from Elam, now in a private collection, and is dated to the third mil-

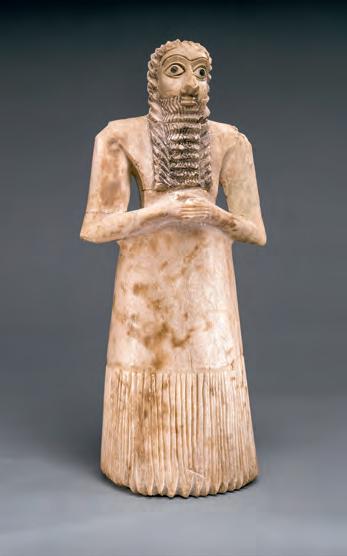

lennium BCE. This sculpture, cut out of limestone, is 8.3 centimetres high and represents a striking muscular woman with the head of a lioness. Such figures, which are partly human and partly animal, were already extant in Europe in the ancient Stone Age and, furthermore, both in early Egypt and in the Middle East, where it was believed that power over the physical world could be acquired through the combination of the superior properties of different species. Dated a few centuries later are Sumerian priest figures carved from alabaster with wide-open staring eyes. Their lower bodies were clothed in long woollen robes (FIG. 244). Even before the birth of the Neo-Assyrian empire in the tenth century BCE, there were small three-dimensional votive statuettes from Ras Shamra made of terracotta, stone, gold, silver and bronze, such as a bronze figure representing the god Baal (FIG. 245). Well known from the Assyrian Empire (c. 150 0–612 BCE), the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626–539 BCE) and the Persian Empire (559–331 BCE) are the cylinder seal rollers and monumental relief sculptures of gods, people and animals fighting each other. However, these cultures also produced small freestanding sculptures of stone, alabaster, bronze and ivory. Just like the reliefs, they mainly portray gods, powerful rulers and animals.

The earliest precursors of the ceramic or white marble Cycladic idols date from around 7500 BCE.467 In most cases they concern female figures. They were found not only on the Greek Cycladic islands but also on Cyprus, on Malta, in Asia Minor and even