Angelika Nollert

84,9 Kilometer zur Kunst

84.9 Kilometers to Art

Petra Hölscher 22

Sigurd Bronger Das Seltsame und das Wunderbare

Sigurd Bronger The Weird and the Wonderful Paul Derrez

Knut Astrup Bull

48 – 235

Trag-Objekte Wearables

144 Unruhestifter

Eine Einführung in die absurde Kunst von Sigurd Bronger

210 Trouble Maker A Starter’s Guide to the Absurd Art of Sigurd Bronger

Céline Robin

237 Anhang Appendix

4 Vorwort Preface

6

14

28

34 Heimkehr

des

42

Transition

in einer Zeit

Übergangs

Homecoming in a Time of

84,9 Kil o � e t e �

84,9 Kilometer zur Kunst

Petra Hölscher

�u r � un s�

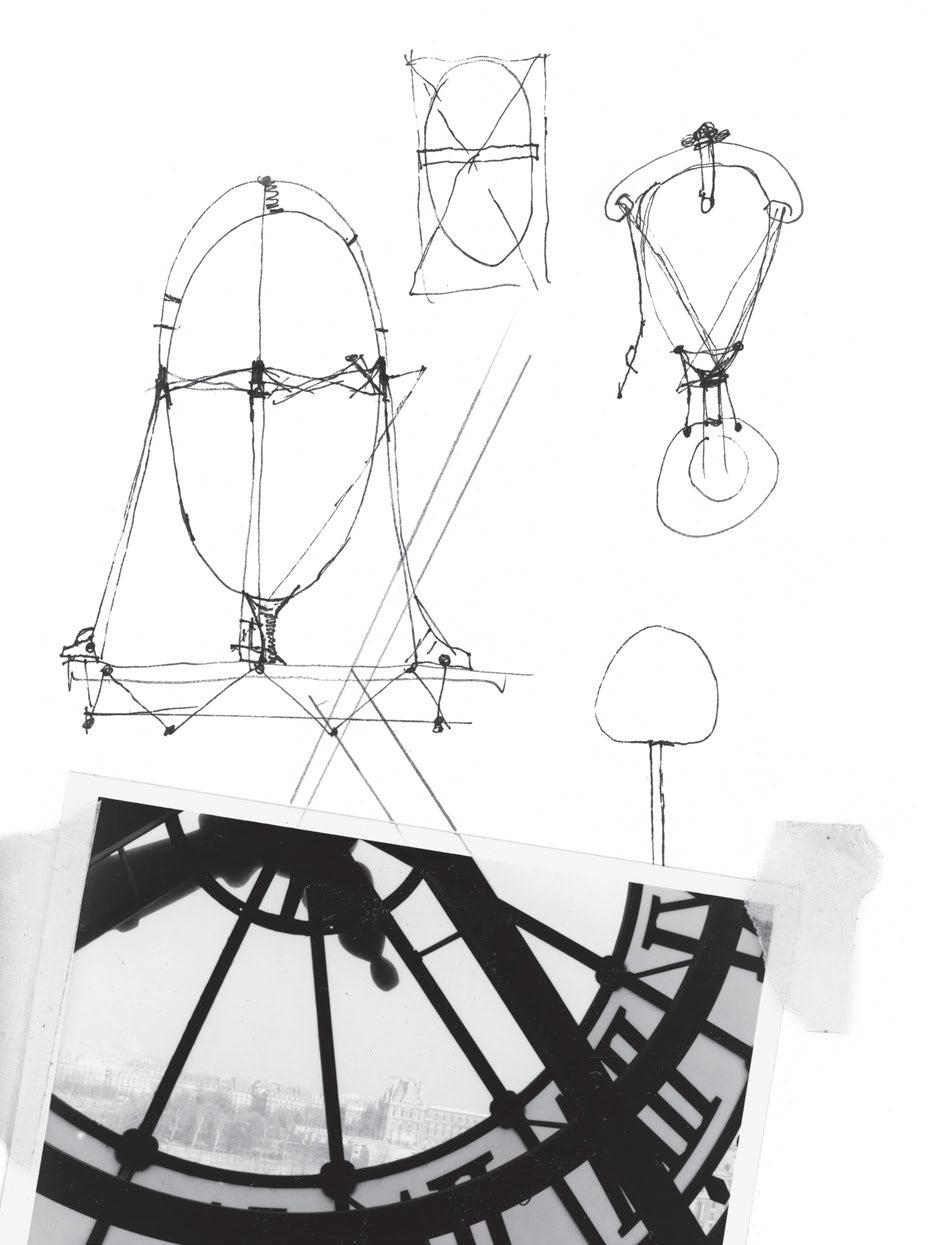

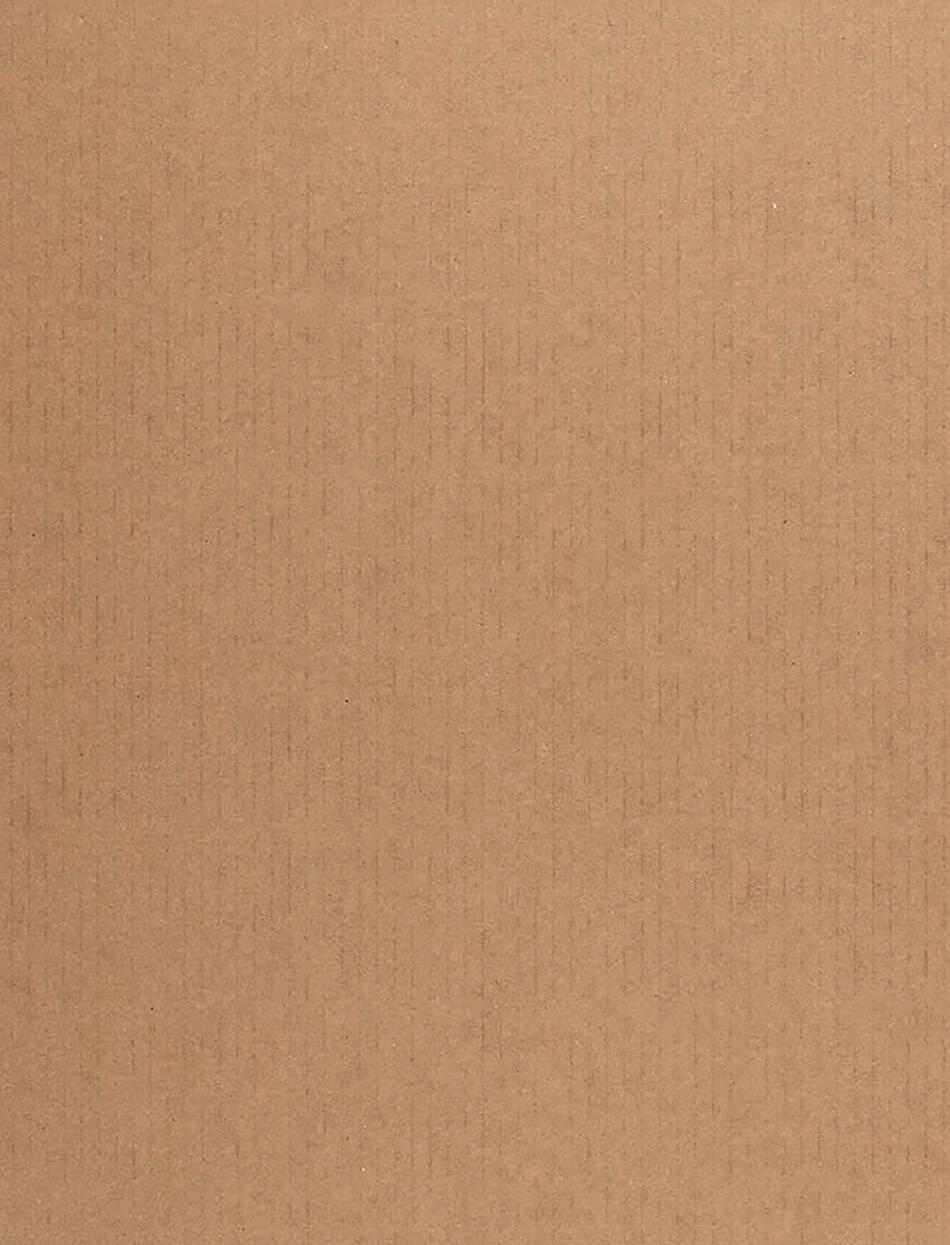

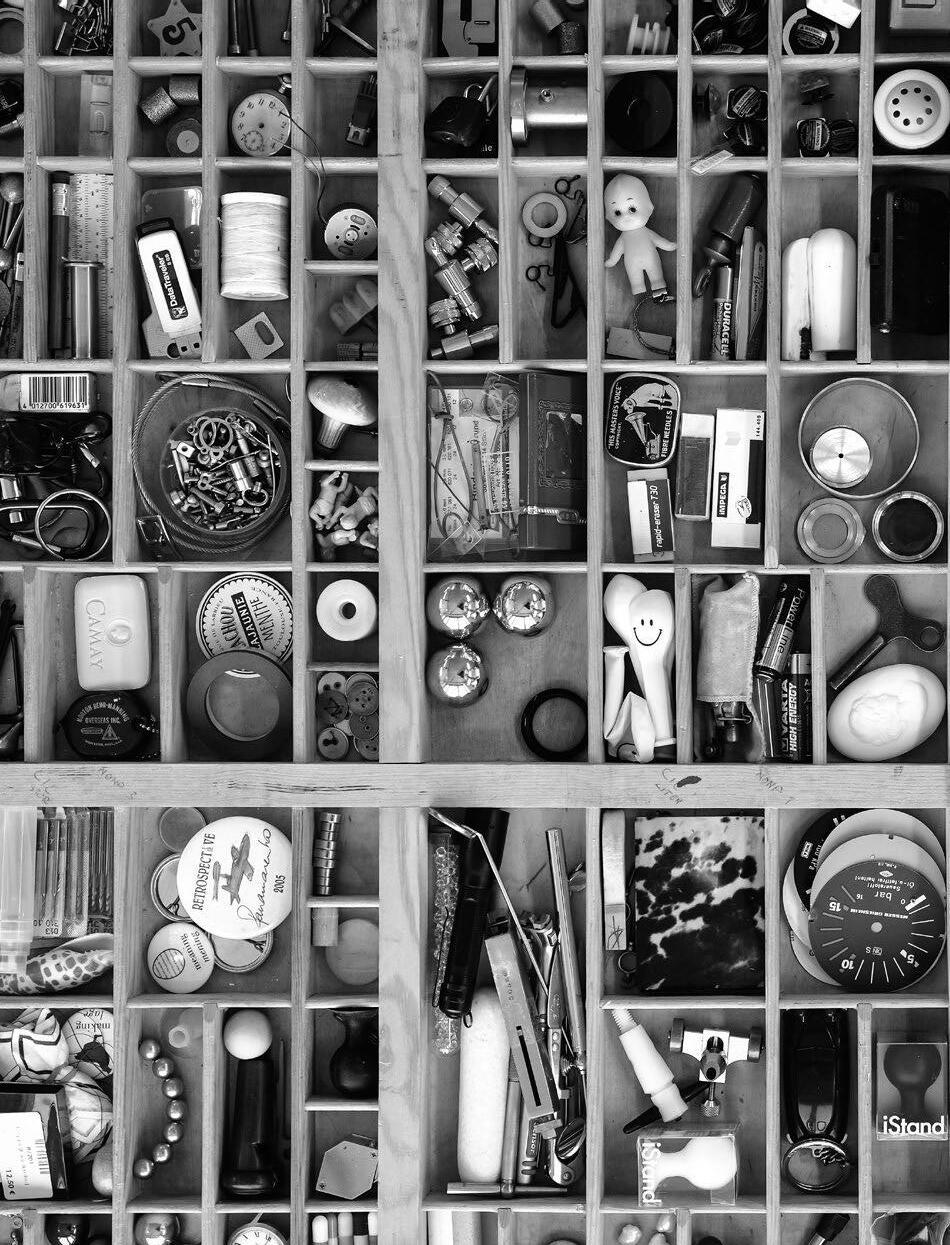

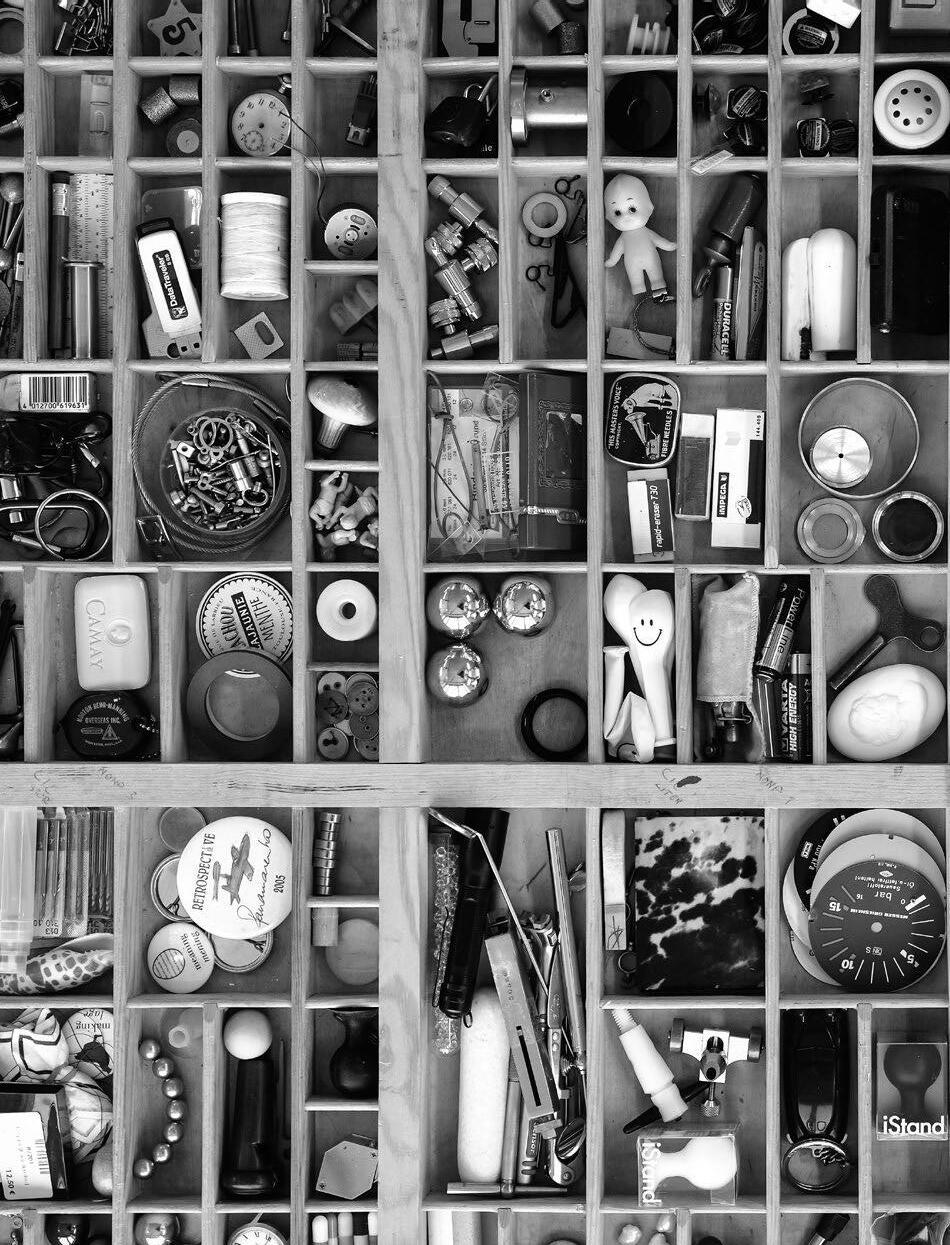

Würde man heute eine Umfrage unter den Schmuck-Aficionados starten, dann hätte sie sicher zum Ergebnis, dass Sigurd Bronger zu den etabliertesten Schmuckkünstlern gehört. Es ist noch gar nicht lange her, da war das nicht so. Einen großen Anteil an dieser positiven Veränderung haben Brongers bekannteste Objekte – die Smileys und die Gänse-, Hühner- und Enten-Eier. Doch wer kennt die amorphen Formen im Frühwerk des Norwegers? Wer ahnt, dass hinter ihnen und den Arbeiten mit delikaten Tragevorrichtungen die Auseinandersetzung mit dem künstlerischen Gedankengut der 1960er Jahre steht, insbesondere dem der Benelux-Länder. Darum soll es hier gehen.

Brongers Weg in die Schmuckwelt beginnt in Oslo in der Goldschmiedeklasse an der Yrkesskole mit der charakteristischen amorphen Formenwelt der 1970er Jahre Seite 202, die wir Hans Arp und seiner an der Natur orientierten Formgebung verdanken. Tatsächlich hegten Surrealisten wie Arp in ihrer Beschäftigung mit dem Lebensalltag ein großes Interesse an Natur und Naturwissenschaften.1 Das niederländische Schoonhoven und die dortige Fachschule (MTS Vakschool) werden Brongers nächste Stationen. Als er die Schule nach drei Jahren verlässt, entwirft er ein dreiteiliges, zartes Ringgebilde Seite 222, bei dem insbesondere die Art der voluminösen, tropfenartigen Krabbenfassung den genaueren Blick verdient.

2 https:// de.m.wikipedia. org, Stichwort ‚Schoonhoven‘, aufgerufen am 1. Nov. 2023.

1

Nadine Engel, Surrealismus und Wunderkammer: Befragung eines Topos der Moderne und Ansätze zur Archäologie eines Sammlungsraums der Frühen Neuzeit (München 2016 [zgl. Mainz, Johannes Gutenberg-Univ., Diss. phil. 2013]), S. 113. Für die zur Verfügungstellung des Druck-PDF danke ich der Autorin.

3 Ausstellung Aftermath of Art Jewellery, Vigeland Museum, Oslo, und Villa Stuck, München, 2013.

4

Siehe Artikel von Paul Derrez in dieser Publikation, S. 22 – 27.

Dass für einen 21-Jährigen, der in der „romantischen, typisch holländischen Kleinstadt“ 2 Schoonhoven seine Ausbildung erhält, die Anziehungskraft Amsterdams Ende der 1970er Jahre immer noch ungebrochen groß ist, darüber muss nicht lange nachgedacht werden. Wohl aber über Brongers Fokussiertheit, die bei allem ‚Sex, Drugs and Rock ’n’ Roll‘, politischem Interesse und Hausbesetzer-Dasein den Besuch in der Galerie Ra miteinschließt. Sie ist nicht nur in den Niederlanden die Galerie, die wie keine andere in dieser Zeit für den jungen, internationalen Schmuck steht. Nur zu leicht lassen wir uns heute durch das ruhige Auftreten des Mannes aus Norwegen und seine perfekt umgesetzten Werke von der Spur abbringen, dass wir es eigentlich bei ihm mit einem ‚Alt-68er‘ zu tun haben, wenngleich er erst 1957 geboren ist. Manchmal bekommt man eine leise Ahnung von Brongers wahrem Background – etwa, wenn er 2013 in München eine Ausstellung nach dem gleichnamigen Rolling Stones Album von 1966 Aftermath benennt.3 Doch zurück nach Schoonhoven. Man lernt Sigurd Bronger als ausgesprochen neugierigen, wissbegierigen und kunstinteressierten Twen kennen, der aus Oslo kommend den Luxus von wechselnden, nationalen wie internationalen Schmuck- und Kunstausstellungen in vollen Zügen genießt.4

8 Petra Hölscher

Von Schoonhoven aus besucht Bronger auf einem Klassenausflug 1978 das Kröller-Müller Museum.5 Es sind nur 84,9 Kilometer bis zu diesem, nicht nur aufgrund seiner Lage einzigartigen Museum in der Nähe von Otterlo. Der belgische Architekt und Künstler Henry van de Velde bettete es Mitte der 1930er Jahre in den Nationalpark De Hoge Veluwe ein. Im August 1978 zeigt man hier eine der ersten Retrospektiven des belgischen Künstlers, Ingenieurs, Physikers und Poeten Panamarenko (eigentlich Henri Van Herwegen, 1940 – 2019). Das dort Gesehene und die Ideenwelt des heute nur mehr selten Erwähnung findenden Künstlers aus Belgien wird Bronger nicht mehr loslassen. Noch heute erzählt er so lebendig von dieser Ausstellung, dass man meinen könnte, er hätte sie erst gestern besucht. Panamarenko wird mehr und mehr zu Brongers „Bruder im Geiste“, zu dem sich mit der Zeit noch ein weiterer Belgier gesellt: Guillaume Bijl (geb. 1946), der Ende der 1970er Jahre die gängige Kunstproduktion kritisiert. Aus seiner Sicht ist „alles zu intellektuell, zu konzeptionell, zu abstrakt“.6 Zu Panamarenko findet sich heute eine sehr umfangreiche Spezialbibliothek mit raren Publikationen in den Regalen von Brongers Werkstatt in Oslo. Dort begrüßt den Besucher ein Plakat, das Panamarenkos wichtigste Erfindungen vorstellt.

5 Siehe Interview von Céline Robin mit Sigurd Bronger in dieser Publikation, S. 144–153. 6

Ausst.-Kat., Naakte Schoonheid: Paradoxe des Alltags, Museum van

Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen und Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus München, 1991, hier: Guillaume Bijl, S. 59 – 63, hier: S. 59. Für den Hinweis auf den Katalog danke ich Otto Künzli.

7

Hans Theys, Men with Gusto: A Few Words on Pop Art, Panamarenko and Marcel Broadhaers (14 pages), http://hanstheys.ensembles.org, aufgerufen am 10. Nov. 2023.

8

Siehe Interview von Céline Robin mit Sigurd Bronger in dieser Publikation, S. 144–153.

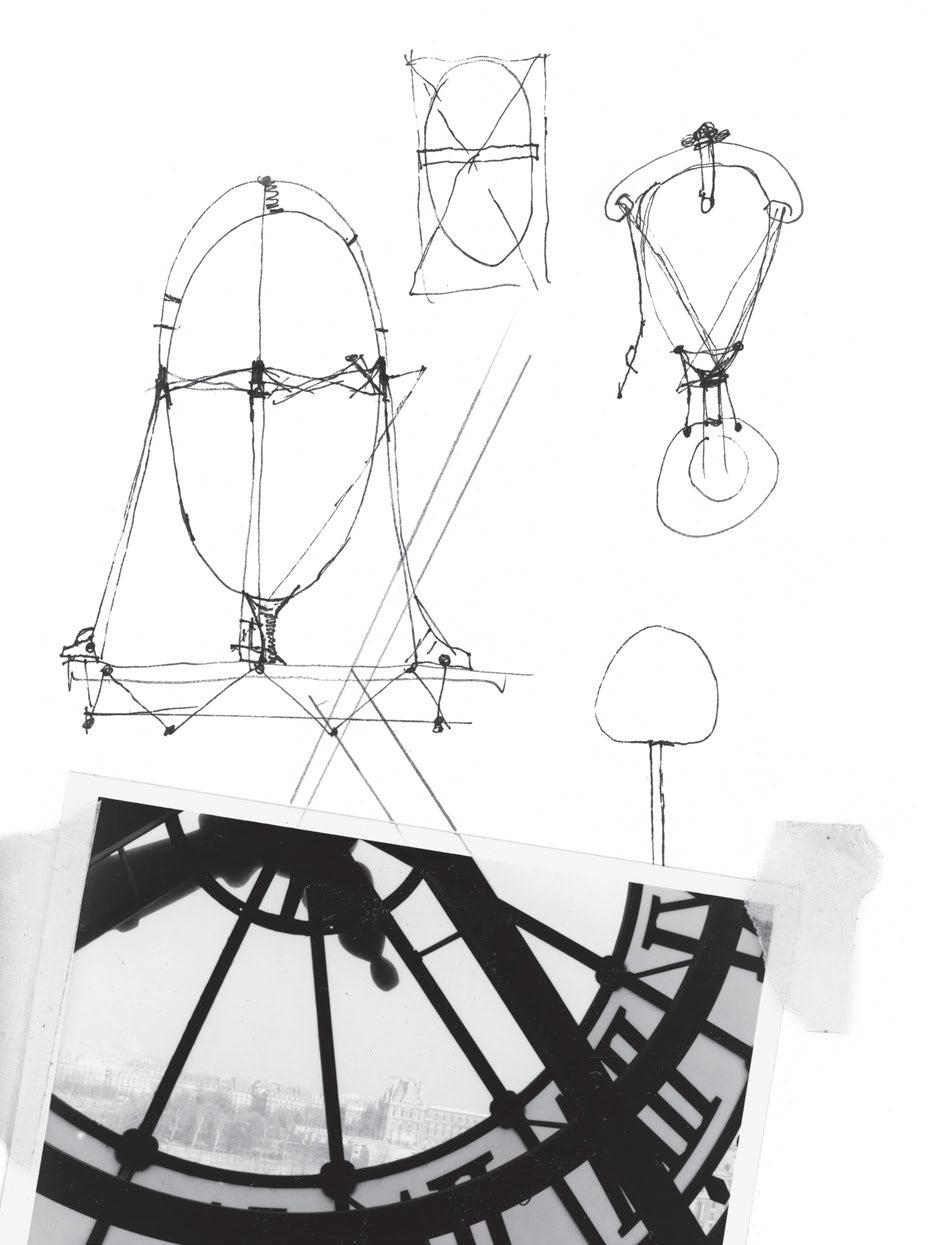

Der Belgier gilt als Visionär der Lüfte, der mit seinen fantasievollen, manchmal nur für wenige Minuten funktionierenden Flugobjekten für die Kunst der damaligen Zeit neue Wege öffnet. Der Philosoph und Panamarenko-Biograf HansTheys stellt fest, dass der belgische Freigeist junge Kunstformen wie die Pop Art mit all ihren gewonnenen Freiheiten für sich zu nutzen wusste. Die Ideen der Pop Art-Bewegung, die sich mit dem täglichen Lebensumfeld auseinandersetzten, schlossen ganz zu Beginn, zwischen 1953 und 1958, auch technische Thematiken mit ein. Technik und Kunst näherten sich an, ja die Grenzen wurden zunehmend als fließend verstanden. Pop Art bedeutete deshalb für Panamarenko auch eine „form of freedom“, denn – Zitat Panamarenko – „I was convinced that from that time one could realize simply everything, in all disciplines, every wish or dream“.7 So mag sich auch Brongers Antwort auf die Frage erklären, in welche Zeit er gerne noch einmal zurückgehen würde, nämlich in die 1950er/1960er Jahre.8

9

Beide Zitate: Hans Theys (s. Fußnote 7).

Panamarenko erwartete von der Kunst, dass sie „surprise[s] him and allow[s] him to see things in a different way“. Entsprechend offenbaren Panamarenkos Arbeiten „new things, broadens the view, embraces as much of the world as possible“.9 Seine ‚made-by-hand‘ Flugkonstruktionen aus Draht, bespannt mit Kunststofffolie, zum Halten

9 zur Kunst 84,9 Kilometer

Home co � � n � �n a

Homecoming in a Time of Transition

Knut Astrup Bull

T� �� of �r a ns i �io �

In 1983, after living in the Netherlands for ten years, Sigurd Bronger returned home to Norway. In Amsterdam he had experienced a diverse and experimental jewelry scene. There were many galleries for jewelry and there was a large group of internationally oriented artists who explored jewelry as an autonomous art form. In Norway the situation was different. Jewelry making was defined as a craft, and most people associated it with use and design. The preferred materials were silver and other precious metals. There were no private collectors, no galleries showcasing jewelry, and the field of jewelry was small.

At the right time

When Bronger established his workshop in Oslo in 1983, jewelry was not seen as a separate field but as a subcategory of metal art. In 1982 the Norwegian Association for Arts and Crafts had about 50 members listed as metal artists, but most of them worked with jewelry.1 It must have been quite a transition to move from an environment that ranked artistic expression and conceptual content above craftsmanship and functionality, to a more tradition-bound jewelry scene. Bronger describes it as shifting from an art scene in Amsterdam to silversmithing in Oslo.2 The Norwegian jewelry scene would, however, change remarkably during the 1980s. Even though Bronger describes his homecoming as difficult, one can see with hindsight that he returned at the right time. When he set up his artistic practice in Oslo, it happened at the same time as a new group of jewelry artists graduated from the National College of Art and Design, established the cooperative workshop TRIKK (engl. tram). Together with TRIKK, Bronger would make his mark on the development of Norwegian jewelry art, and he eventually became a member of the group.

1 Toril Bjorg, ‘Norsk metallkunst 1982’, Kunsthåndverk no. 9 / 10, 1982.

2 Conversation with Sigurd Bronger, 24th October 2023.

3 Conversation with Millie Behrens, 20th October 2023.

Millie Behrens (b. 1958), Kyrre Andersen (b.1958), Tove Becken (b.1952), Morten Kleppan (b.1958), Leif Stangebye-Nielsen (b.1955), and Liv Blåvarp (b.1956) established TRIKK in 1983. Several of these artists had lived and studied abroad and, like Bronger, were well-versed in international design and jewelry. TRIKK’s stated ambition was to orient itself internationally and to experiment with materials and forms.The members and Bronger shared the same strategic and artistic ambitions. TRIKK did not have a common manifesto. Each artist worked individually on his or her own projects, but as a group, they wanted to make Norwegian jewelry internationally relevant.3

44 Knut Astrup Bull

Climate change

TRIKK represented a new orientation in jewelry art as much as a start-signal for the establishment of New Jewelry in Norway.4 The climate change happened during a few hectic years in the mid-1980s. Other jewelry artists also contributed to the new orientation, but TRIKK was without doubt a key driver in the development. As Liv Blåvarp puts it, “We liked to see ourselves as the engine for a large and radical movement in our professional field”.5

5 Anne Britt Ylvisåker, ‘Wood – The Real Deal – Jewellery Artist Liv Blåvarp’, in Liv Blåvarp. Jewellry: Structures in Wood, ed. by Anne Britt Ylvisåker and Cecilie Skeide, Lillehammer Kunstmuseum (Stuttgart 2017), p. 23.

6 Exh. Cat., TRIKK, Galleri Albin Upp (Oslo 1984).

4

Jan-Lauritz Opstad, ‘Den nye smykkekunsten’, Kunsthåndverk no. 22, 1986.

TRIKK’s fresh approach to jewelry was seen at the group’s first exhibition, held at Galleri Albin Upp in Oslo in 1984. In this exhibition, the members presented jewelry that resulted from experiments with materials such as wood, plastic, aluminum, and, not least, the new so-called aerospace materials titanium and niobium.The material experiments were what largely united the group.6 Another unifying factor was the bright color palette. Through the use of materials and colors, TRIKK’s jewelry distinguished itself from the foregoing generation’s modernistic expression, in which organic forms, shiny silver, and daubs of brightly colored stones or enamel were dominant. The exhibition was well received amongst jewelry professionals and the public. The jewelry pieces seemed fresh in form and material use, and they incorporated the Postmodern current that in several ways broke away from Modernism’s dogmas. TRIKK members and many of their colleagues played with Modernism’s visual language by turning everything on its head, as it were. Sigurd Bronger, for his part, was fascinated by Modernist movements such as De Stijl and Bauhaus. He played with primary colors, geometrical forms, and constructions in the raw. What distinguished his expression from that of Functionalism was that his jewelry, rather than being rationally constructed, was absurd in all its complicated simplicity. Geometrical shapes, bright colors, and non-traditional materials are common denominators for the new Norwegian jewelry of the 1980s. TRIKK’s and Bronger’s works kept an ironic distance from Modernism, and their playful attitude towards it clearly demonstrated the values that differentiated the New Jewelry generation from the foregoing generation. Experimentation was central, and with that, artistic expression was emphasized more than function. In general, however, one can say that the functional aspect was still important for the makers. Seen in an international context, Norwegian New Jewelry must therefore be described as more moderately experimental than, for example, that of the Netherlands. Even though functionality and handicraft were important criteria for the Norwegians, they shifted the field of jewelry from design and applied arts towards a more autonomous art form.

45 Homecoming in a Time of Transition

�ear

Brosche Brooch Sustainable Construction No 032 3

3,5 × 3,5 × 3,5 cm Pappschachtel, Silber, Stahl, Messing

Cardboard box, silver, steel, brass

Privatsammlung Private collection

Brosche Brooch Reflection 5 × 4,5 × 1 cm

Mineralglasspiegel, Silber, Stahl

Mineral glass mirror, silver, steel

2017

2023

Privatsammlung Private collection

70

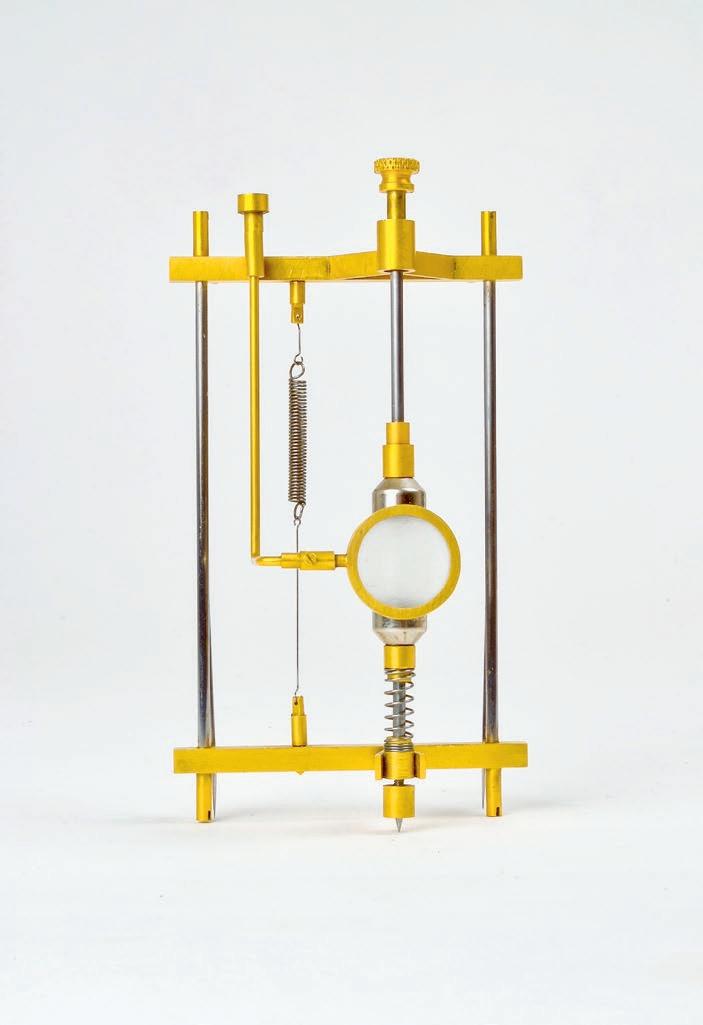

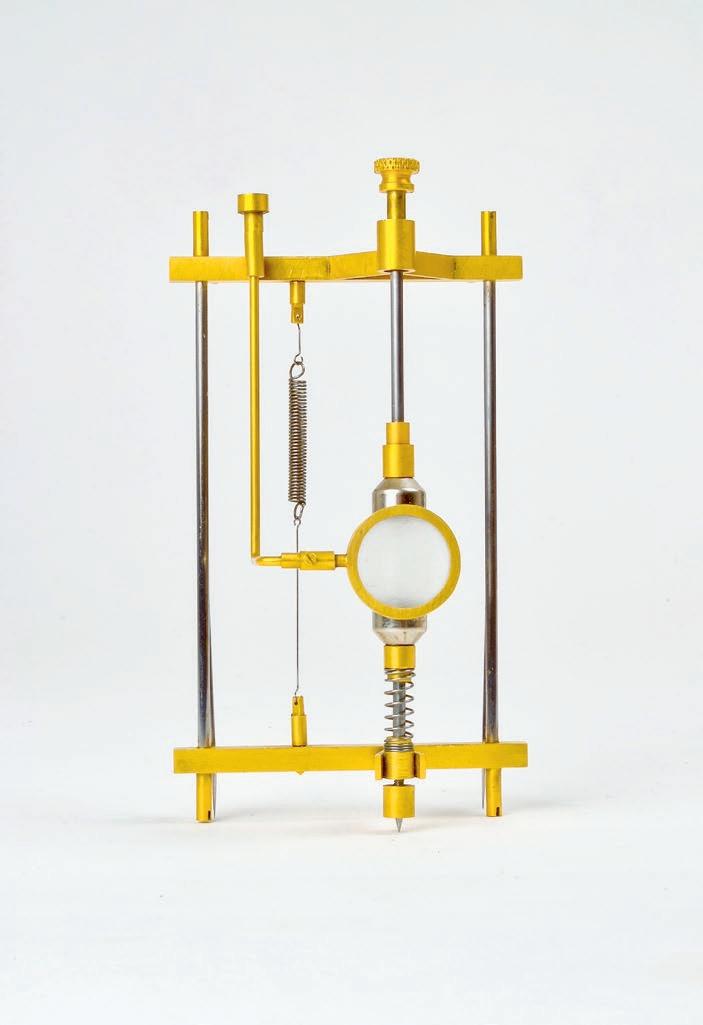

13 × 6 × 4,5 cm

Leuchtmittel, vergoldetes Messing, Stahl, Glas

Light bulb, gold-plated brass, steel, glass

Privatsammlung Private

collection

1998 Brosche Brooch Carrying Device for a Light Bulb 71

20 × 11 × 6 cm Hartschaum, Stahl, Silber, Lack, Gummi, Fahrradventil Hard foam, steel, silver, lacquer, rubber, bicycle valve

1994

Blow

Armschmuck Bracelet

Up!

Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustrimuseum, Trondheim

73