Goff Books

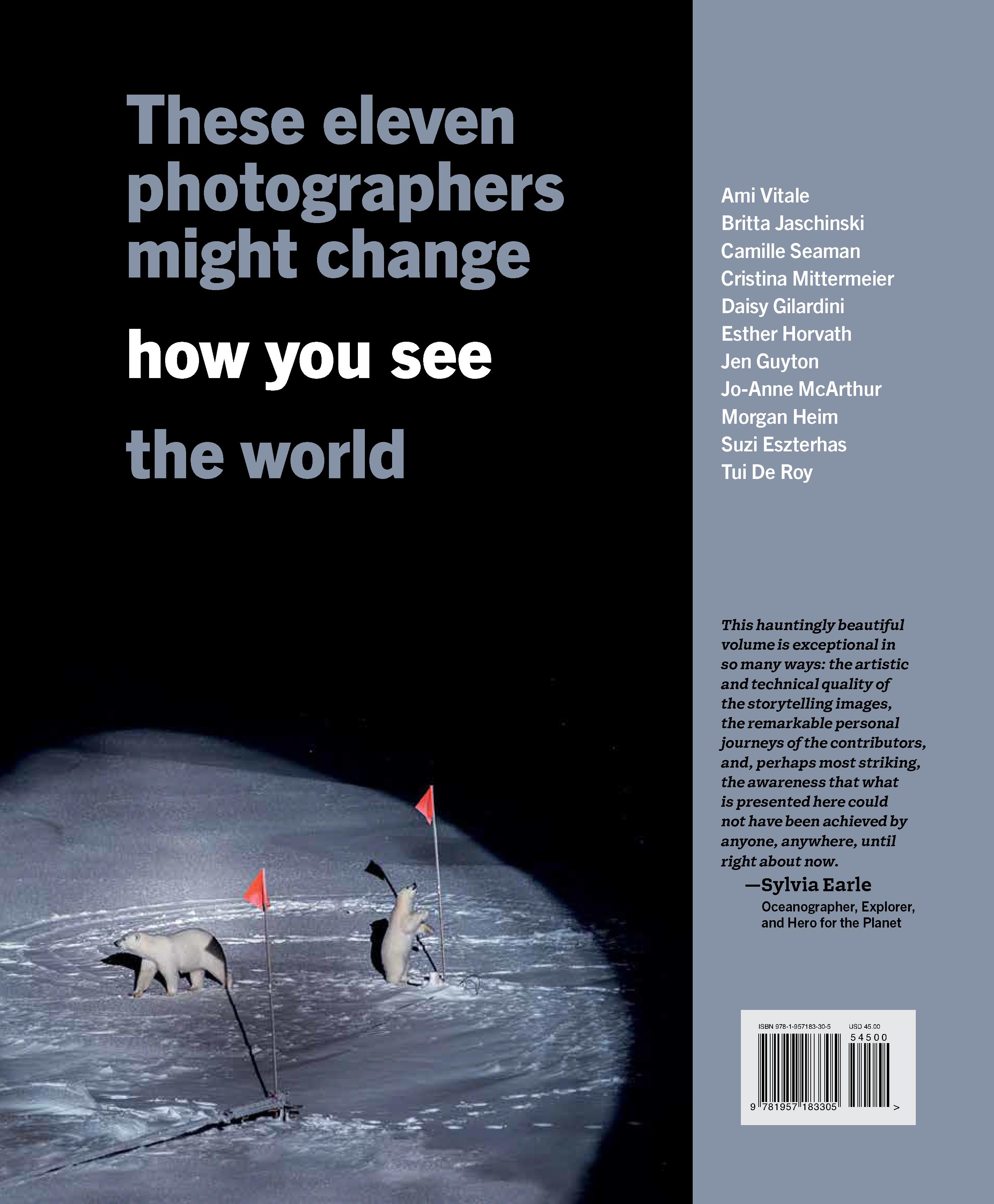

On the cover: An iceberg in Antarctica’s Lemaire Channel, photographed by Camille Seaman.

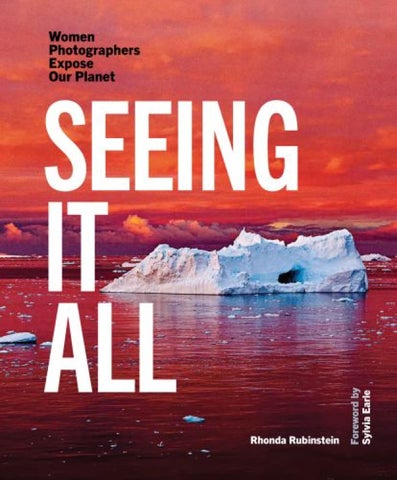

An uphill climb for a pair of chinstrap penguins, photographed by Daisy Gilardini.

On the cover: An iceberg in Antarctica’s Lemaire Channel, photographed by Camille Seaman.

An uphill climb for a pair of chinstrap penguins, photographed by Daisy Gilardini.

4

Foreward by Sylvia Earle

Rhonda Rubinstein: Seeing through her eyes

8 12

Rebecca Solnit: Seeing is the beginning of caring

Ami Vitale For us to thrive, the animals too, must thrive.

Britta Jaschinski Our insatiable demand for wildlife products is pushing animals to extinction.

Camille Seaman Meet your ancestors in every aspect of nature, large and small.

Cristina Mittermeier The ocean is the solution to climate change.

Daisy Gilardini Cute and cuddly make the case for conservation at Earth’s extremes.

Esther Horvath Witness the indisputable science of climate change in the Arctic.

Jen Guyton Change starts at the convergence of culture and environment.

Jo-Anne McArthur Every animal is an individual: a complex, sentient being.

Morgan Heim Photography elevates the controversial, misunderstood, and underappreciated.

Suzi Eszterhas Revealing glimpses of newborns in the wild inspire our humanity.

Tui De Roy On the world’s most biodiverse archipelago, there’s so much to save, yet so much to lose.

Goff

Seeing our moment in time

Recognized as a ‘Living Legend ’ by the Library of Congress, Dr. Sylvia Earle is the President and Chairman of Mission Blue and a National Geographic Society Explorer in Residence. She has authored more than 225 publications and logged over 7,500 hours of underwater expeditions, including leading the first team of women aquanauts in 1970. As an oceanographer, and explorer, her research concerns the ecology and conservation of marine ecosystems and development of technology for access to the deep sea.

Goff Books

This hauntingly beautiful volume is exceptional in so many ways: the artistic and technical quality of the storytelling images, the remarkable personal journeys of the contributors and, perhaps most striking, the awareness that what is presented here could not have been achieved by anyone, anywhere, until right about now. Unless urgent action is taken very soon, most of the creatures portrayed here may not exist in the wild in a few decades.

In just half a century, advances in technology have made it possible to navigate to, and spend meaningful time in, places that were previously inaccessible, with equipment— including photographic gear—that would make pioneering explorers and photographers gasp with wonder. Ironically, more and more people now are able to be in the presence of fewer and fewer wild animals in patches of wilderness squeezed within increasingly tamed spaces, on land and sea.

In late 2022, 188 nations pledged to safeguard in a natural state at least 30 percent of their land and freshwater systems and 30 percent of the ocean by 2030. It’s an ambitious goal since at the time only 15 percent of Earth’s land mass and three percent of the ocean globally experienced a high degree of official protection from destructive human uses. Current trends will result in the loss of more than a million species by the time today’s children have grandchildren.

There is still time (though not a lot) to shift from foreseeable 21st-century tipping points of loss to decisive turning points of recovery and eventual harmony with the fabric of life that underpins our existence. Knowledge is the key to securing an enduring future for ourselves and all that we care about: our health, wealth, security, and, most critically, our very lives.

With knowing comes caring, and with caring comes hope that we can and will find a place for ourselves within the natural, living systems that set Earth apart as a small, blue miracle suspended within the magnificent but extremely hostile universe beyond. The evidence—facts, figures, charts, and graphs—have made it clear that our planet is in trouble, and therefore so are we.

Since the 1950s, more has been learned than during all preceding history about who we are, where we have come from, and where we might be headed. But at the same time, more of Earth’s ancient systems have been lost, displaced, or consumed by our growing numbers. Knowledge alone has not been enough to inspire the actions needed to shift the trajectory of decline.

Bravo to the 11 champions profiled here. They are using the power of art, of empathy, of connecting “us” with “them,” with an underlying message of hope that we can and will care enough and act soon enough for tomorrow’s children to not just wistfully view beautiful images of wondrous extinct creatures, but to experience a robust reality of dolphins, elephants, pangolins, and people living together in peace.

At a time when smartphones enable almost everyone to take photographs of almost everything, what makes the images here, the photographers, and their stories so compelling? Notably, most professional photographers, and especially most wildlife photographers are men. Does gender matter? Is there a way to tell by looking at a photograph whether a woman or a man was behind the lens? On viewing images by a noted female photographer, Gilbert Grosvenor, for years the editor of National Geographic magazine, suggested that, “Women often see things about life and ways of people that a man would not notice.” If so, what might those things be? Do men see things a woman would not notice?

Goff Books

One thing is certain. The images in this book were created by mothers, sisters, aunts, and daughters, each an individual who did not wait for society to catch up with their need to be creative, their drive to apply their knowledge and skills, and their keen desire to foster harmony between humans and nature. They have not only excelled in the art of making images that speak volumes, they have done so while dealing with resistance not experienced by their male colleagues, with skill, humor, and the grit to make a difference, no matter what.

Rhonda Rubinstein is a creative director and curator who applies the capacity of design, photography, and language to express the critical ideas of this planetary moment. She works in all media in her role as Creative Director of the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, where in 2014 she cofounded the BigPicture Natural World Photography initiative. Her previous book is Wonders: Spectacular Moments in Nature Photography

Seeing through her eyes

A deep sadness came over me when I heard the news about Pikin. We were immersed in the production of this book, checking facts, when contributing photographer Jo-Anne McArthur wrote to say that the young lowland gorilla had died. Jo-Anne’s tender photo captured a moment in transit as Pikin clung trustingly to her caretaker, Appolinaire, his arms gently surrounding and soothing her. Pikin was no longer living a better life in a primate sanctuary in Cameroon. Her story had ended.

As my heart dropped, I wondered why I had become so attached to an animal I had never met, and known only from a black-and-white photo. Then I realized. I had seen Pikin through the eyes of her compassionate caretaker as manifested through the camera of a truly empathetic photographer. That intimate image helped me see the gorilla as an individual and become curious about her hero caretaker and the organization that rescued her.

I was seeing it all differently.

Which is what this book is all about. Photographers often see what other people don’t, and when they have borne witness we get to see it through their eyes. Photographers bring their subjects into focus, framed by their own ideas and unique perspectives.

At this critical moment in time, we need to see ourselves and our planet— and the inextricable connection between those two entities—through a new lens. We invited 11 groundbreaking photographers to share their philosophy and photography in this time capsule, commonly referred to as a book. The photographers, whether renowned for their work in documentary, wildlife, or conservation photography, expose how we—humans, animals, nature— are living together in these precarious times. Each photographer’s concise manifesto reflects their insights from seeing and documenting the world— from deep oceans to distant islands. These 11 photographers are women. Their images reflect their unique and compassionate worldview of an interconnected planet.

Goff Books

But we can also see ourselves reflected in these photographs. Not just in the wildlife caretakers, researchers, and other humans. Nor in the common ancestry we share with a playful young orangutan or the emotional connection felt with devoted penguin parents. But beyond that. Humans are everywhere. Or at least traces of us are— microplastics have been found from Arctic ice cores to the bottom of the ocean. And when we look at the images in this book, we can see how humans are driving species to extinction, turning animals into commodities, and simply ignoring them as road casualties. It is hard to view a beautiful photograph of an iceberg without reflecting on how we are quickening its disintegration.

Almost a century ago, Dorothea Lange, a pioneering female photographer in the early days of photojournalism, photographed a hopeless woman huddled with her children in order to raise awareness of the urgent need for national aid during the Great Depression. Within days of the publication of Migrant Mother in 1936, the government sent 20,000 pounds of food to the farmworkers. Lange’s unique and compassionate eye produced one of the most iconic, change-inspiring photographs of the 20th century.

The image was featured in the seminal Family of Man exhibit at New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1955, which Lange helped her friend, Edward Steichen, curate. (Today, one might wonder about conceiving a family without women.) That ambitious exhibit aimed to show the universality of the human condition and relationships, from birth to death, with images selected from around the world.

In the 21st century, the compassion, community, and connection to other people that Lange and the Family of Man revealed must now be extended to our more distant relatives: animals, plants, and the planet itself. That is also visible in these pages. Ami Vitale’s formidable photograph of Sudan—the last male northern white rhino—as he lay dying with his caretaker Jojo, was one of only two frames created by Ami during a moment of mourning. The image became the cover of National Geographic and, seen around the globe, has become an iconic representation of the tragedy of extinction.

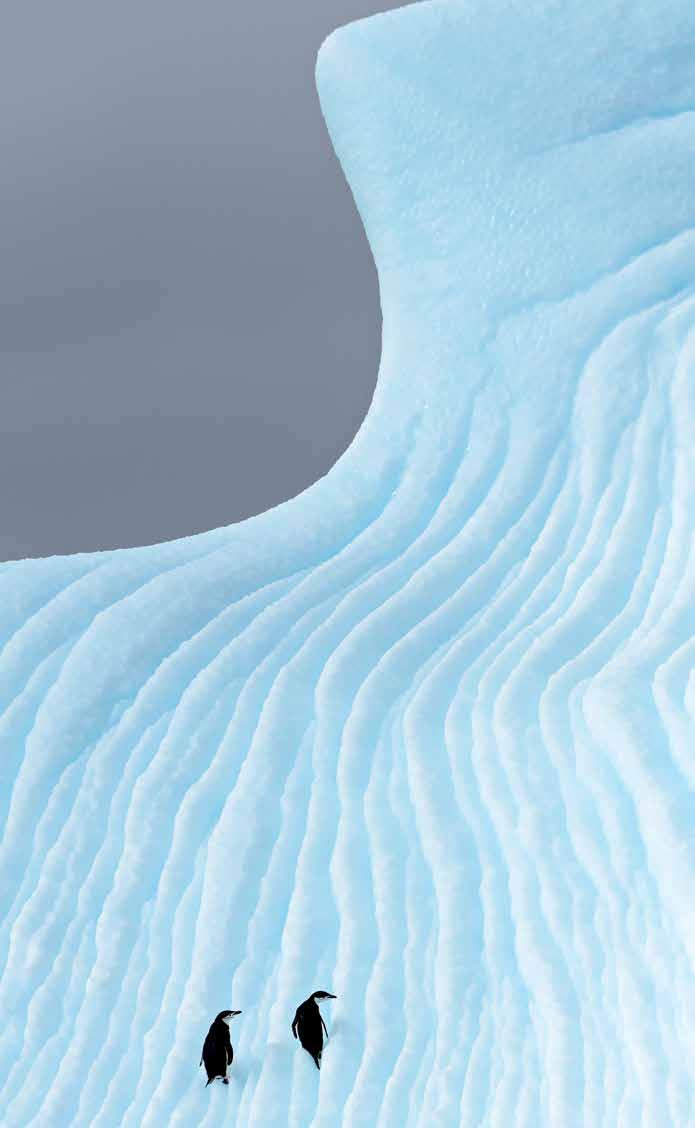

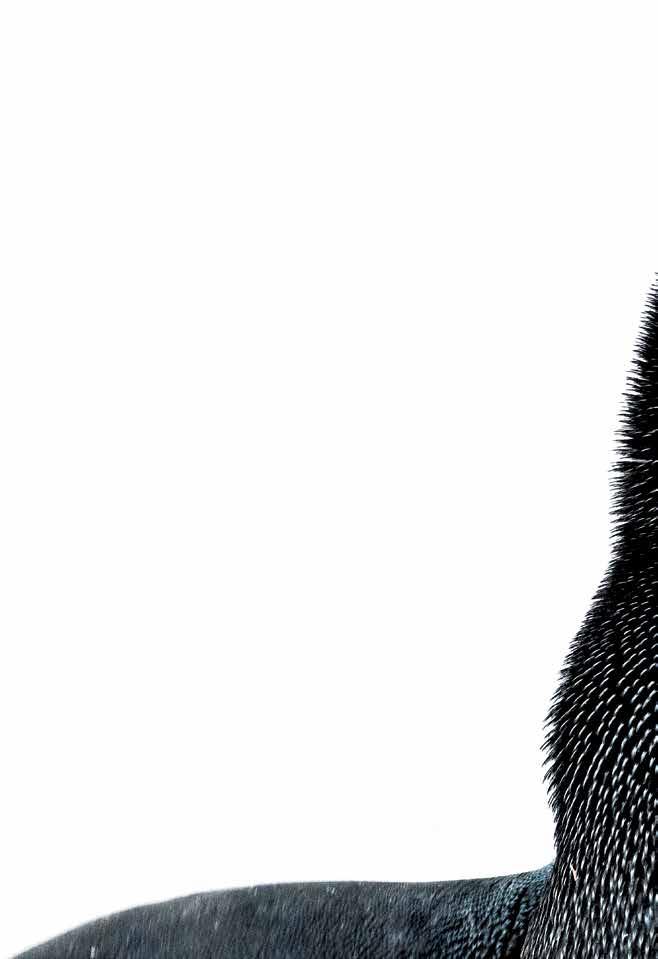

These glimpses of peril exist amidst portfolios of profound beauty. We can easily revel in the joy of sea lions playing among schools of brightly colored fish, or admire the monochrome majesty of the penguin on this very page. It’s harder to look at the mistreatment of animals, the unnecessary deaths, or to accept the impending disappearance of a species. But the beauty of these photographs enables us to look at what we’d rather not see. They connect the seen to the hidden, abundance to disappearance, icebergs to Indigenous portraits, sanctuaries to scientists, and head to heart.

Goff Books

Seeing it all, clearly, unflinchingly, so that others can viscerally see, feel, and understand what is really happening outside their own frame of view. I may never visit Cameroon, but I now know how close it is. That intimate look invites us to really see the state of our planet and hear the compelling arguments for knowing, caring, and for life itself.

Goff Books

For us to thrive, the animals too, must thrive.

Goff Books

Blind, nearly hairless, and just one onehundredth the size of its mother, a newborn panda is as needy as it gets. But change is rapid: the panda is among the fastest growing of mammals, increasing in weight from around 100g to 1.8kg (4oz to 4lb) in its first month. By breeding and releasing giant pandas, boosting existing populations, and protecting vital habitat, China’s scientists and international conservation partners are on their way to saving this emblematic animal, turning it into an ambassador for imperiled species worldwide.

A panda cub is bemused by a session on the weighing scales at Bifengxia Panda Base in Sichuan Province, China.

Adult giant pandas range from 1.2 to 1.9m (4 to 6ft) in length, with females averaging around 100kg (220lb) in weight and males around 115kg (254lb).

They typically live around 20 years in the wild and up to 30 years in captivity.

Goff Books

Captive-bred giant pandas are shielded as much as possible from human contact in order to prepare them for life in the wild. Here, a veterinarian at Hetaoping Wolong Panda Center dons a panda suit while conducting a check-up on a young panda. Sadly, this center was destroyed during the devastating 2008 Sichuan earthquake. A new center has since been built at nearby Gengda, where the painstaking work continues.

The misty, high-altitude forests of Wolong National Nature Reserve provide a suitably atmospheric backdrop for YeYe, a 16-year-old female giant panda being prepared for release into the wild. In 2020, this reserve was incorporated into the new Giant Panda National Park, a much larger area that aims to connect and consolidate all remaining giant panda populations. Meanwhile, the success of China’s breeding program has seen the conservation status of this iconic species downgraded from Endangered to Threatened.

Goff Books

“There are amazing stories happening in China. The panda’s recovery shows that when science, political will and engagement of local communities come together, we can turn things around.”

Cute and cuddly make the case for conservation at Earth’s extremes.

Goff Books

Goff Books

Overleaf: A polar bear cub plays with its mother shortly after emerging from a maternity den in Wapusk National Park, Canada. It’s early March, and the snow is still deep. After a few days, the cub will set off with its mother on the long trek to the sea ice. Gilardini captured this image after hours following the bears’ tracks, using the one-hour window of light before she had to turn back. She has no qualms about invoking sentimentality in her work: for her, a ‘cute’ image can be a powerful way of connecting people to the natural world.

Goff Books

At Volunteer Point on the Falkland Islands a single recumbent king penguin breaks the neat pattern of its upright companions. Gilardini used a drone to capture this arresting image from the air. She believes in the power of technology to help us see the world differently, provided it has no negative effects on her subject. “I always put the welfare of the animal first,” she says.

Goff Books

On Snow Hill Island, Antarctica, an emperor penguin perches on its parent’s feet, incubated from the frozen ground under a warm brood pouch. It is an image that underlines Gilardini’s belief in the power of ‘cute and cuddly’, but also tells a story of extraordinary resilience. Emperor penguins are adapted to withstand the harshest conditions on the planet, breeding during the Antarctic winter when temperatures can plunge to -50°C (-58°F).

“We have to make people care— before it’s too late.”

Photography elevates the controversial, misunderstood, and underappreciated.

Goff Books

Goff Books

Heim found this yearling black-tailed deer on the road in a residential area near Carruthers Memorial Park, Oregon. As with all this series of images, she has lit the subject with a technique called ‘light painting’, using strokes of a flashlight beam during a long exposure. “I know this deer is gone but I feel the need to acknowledge her, to leave her a moment of peace and remembrance despite her violent passing,” says Heim. An estimated 1.23 million deer are hit by vehicles in the US every year.

Goff Books

When Heim’s husband found this garter snake run over in the driveway of their home, he preserved the body knowing that she would want to arrange and photograph a memorial. “Afterwards, I moved the snake to a spot under the ferns and left her with a few of the flowers,” she says.

Goff Books

“I hope that by photographing these species, I can jolt people out of their dislike or indifference or misperception—to stop and see their true beauty.”

On the world’s most biodiverse archipelago, there’s so much to save, yet so much to lose. Goff Books

Goff Books

The golden cownose ray is generally encountered at night, so De Roy was delighted to find a small group feeding at Sullivan Bay, Santiago Island, in broad daylight. This species feeds on crustaceans and other invertebrates, raking the bottom with its plough-like snout and fluttering its ‘wings’ to ruffle up the fine sand. By freediving as the group of rays approached the shallows, De Roy was able to capture a fleeting moment of eye contact with this individual before it disappeared in a cloud of sand.

Goff Books

Goff Books

“When I take these photos of the sea lions frolicking, I want to be one of them.”

“Nature quietly gets on with being, adjusting, and remaining beautiful.”

Goff Books

Goff Books

Goff Books