What did you go out into the wilderness to look at? A reed being shaken by the wind? But What did you go out to see?1

Jesus’ question to John the Baptist Matthew 11:7-8

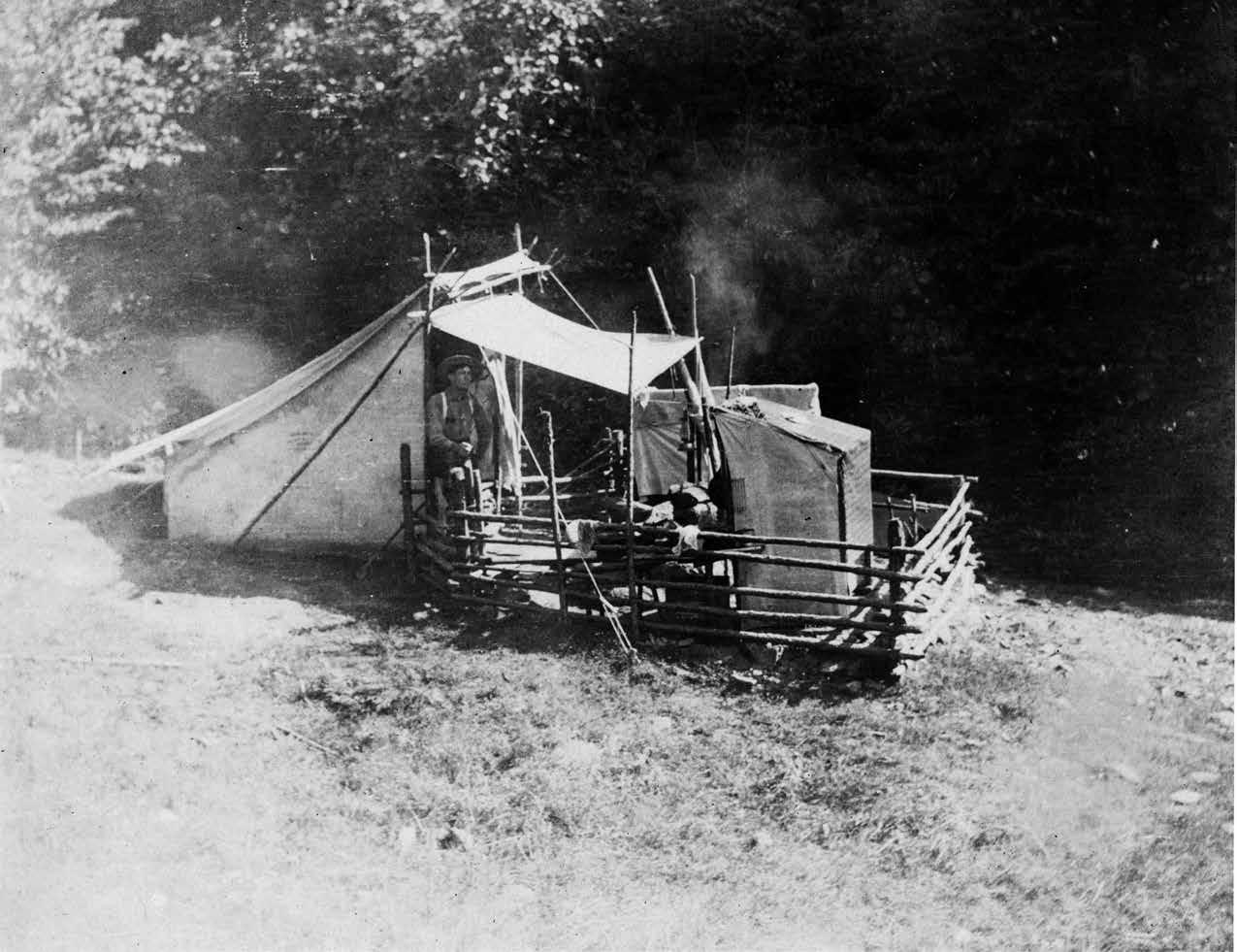

Horace Kephart was to all appearances a success. He was, in 1900, the head of the Mercantile Library in St. Louis, married, the father of five children, and beginning a career as a writer and editor. But 1904 found him a changed man,unemployed, abandoned by his family, recovering from bouts of alcoholism and depression, and living in a tent in the woods to the west of Asheville, North Carolina. Yet none of the problems of his family and career were the sole reason or even the primary reason for his changed circumstances. He later explained: “This instinct for a free life in the open is as natural and wholesome as is the gratification of hunger and thirst and love. It is Nature’s recall to the simple mode of existence that she intended us for. Our modern life in cities is an abrupt and violent change from what the race has been bred to these many thousands of years.”2 He moved into a cabin with the inset of winter, but he never left the Smokies. He was not alone with these impulses.

John Burroughs owned a large, well-furnished house on the Hudson, but in 1896 he largely abandoned it and built a small log cabin for himself about a mile away. He wrote: “The work of reclaiming that wild land seemed to stir the aboriginal instinct in me and I found myself longing for a wigwam or cabin to which I might retire when I was in the mood and live a life of rude simplicity.”3 He stayed there twelve years. When he moved, he moved to another cabin.

In 1879, Frank Cushing was assigned by the US Department of Ethnology to spend three weeks at the Zuni Pueblo in western New Mexico. He spent five years there, learning their language, eating their food, wearing their clothes, learning their history and rituals. He was adopted by the tribe, and left only when the government forced him to.

All of these events took place between 1879 and 1904 and there are many similar stories from the same period of people abandoning not just their daily lives but the civilization that housed them for a life that was in some way archaic, following impulses they saw as intuitive, living the existence nature intended us for. It coincided exactly with Paul Gauguin’s departure from Paris to live a “primitive” life in Tahiti. Gauguin died in the South Pacific. Kephart, Burroughs, and Cushing made a clean, long-term if not permanent break with over-civilization, but there were others for whom escape was temporary. The escape might be for a summer in the Adirondacks.

John Muir, writing in 1901 said: “Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity.”4 Writing in 1981, T. J. Jackson Lears used this same term, overcivilized, to describe a central condition of the period 1880 to 1920:

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, many beneficiaries of modern culture began to feel they were its secret victims. ... American anti-modernism, particularly in its dominant form—the recoil from an 'overcivilized' modern existence to more intense forms of physical or spiritual experience supposedly embodied in medieval or Oriental cultures.5

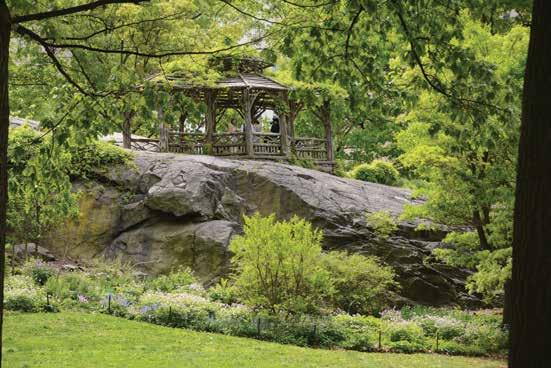

Rustic elements were not confined to the two recreated Adirondacks. There are rustic structures outside the densely wooded areas such as the Ramble, especially on high promontories. As with Downing, an Olmsted and Vaux favorite is the rustic structure with a seat and a view. Two of the most visible sit on rocks along the edges of the park near entries, perhaps a preview of the ultimate destination. The originals are long gone, but they have been rebuilt. They follow the tree or tree grove model used elsewhere, a central cluster of columns in an octagon with cantilevered branches.

The Dene Shelter, also on top of a rock, near Fifth Avenue, is a smaller version of the double-roofed octagon, but with two projecting bays. The second is on a high rock outcrop near the artist’s gate on the south edge at Sixth Avenue, is Cop Cot, which means “little cottage on the crest of the hill” in Scottish. Vaux’s rustic shelters are typically circles, hexagons, or octagons. Cop Cot is an octagon in plan with perimeter columns and log brackets supporting a two-tiered pyramidal roof.

The Dene is a valley that runs south toward the Zoo. Both of these shelters are visible from outside the park and both give views back into the city to those who occupy them. Olmsted and Vaux vigorously opposed a proposal to give the park neoclassical gates, perhaps these shelters were their idea of a threshold.

The log cage trellis structure

The log truss structure

Just before Bernard Maybeck’s death in 1957, a city-wide discussion was taking place in San Francisco about the fate of his most conspicuous building, the Palace of Fine Arts. Built as a temporary building for the Panama Pacific Exhibition of 1915 of plaster casts on hidden wood framing, it was, after 40 years, badly deteriorated. When asked what should be done Maybeck replied:

I think the main building should be torn down and redwoods planted around—completely around— the rotunda. ... As they grow, the columns would slowly crumble at the same speed. Then I would like to design an altar, with the figure of a maiden praying, to install in that grove of redwoods. ... I should like my palace to die behind those great trees of its own accord, and become its own cemetery.2

This was no off-the-cuff remark as it closely parallels what Maybeck had felt about the building when it was built. The Palace of Fine Arts was to be a portrait of a ruin. He wrote in 1915 that it should be:

An old Roman ruin, away from civilization, which two thousand years before was the center of action and full of life, and now is partly overgrown with bushes and trees—such ruins give the mind a sense of sadness. ... Great examples of melancholy in architecture and gardening may be seen in the engravings of Piranesi, who lived a century ago, and whose remarkable work conveys the sad, minor note of old Roman ruins.3

In a 1915 book on the palace Frank Todd wrote: “He has gone back to the classic age for his elementary forms, standing where a young Greek would have stood; and he has come forward again to the present, putting his building

on the edge of a tarn and giving it the melancholy of old ruins by a landscape treatment intended to throw it into the background.”4

Maybeck wrote of the melancholy evoked by the art on display there, which included Arnold Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead, portraying a burial on an island ruin, and said: “we must use those forms in architecture and gardening that will affect the emotions in such a way as to produce on the individual the same modified sadness as the galleries do.”5

This is a type of melancholy we have met before—the melancholy of the English romantics— of William Shenstone, of picturesque ruins. The melancholic contemplation of ruins was a well-established aesthetic pastime by 1915. For Maybeck it had been a far more personal and painful experience. He had seen the ruins of San Francisco after the earthquake and fire of 1906 in which his office and many of his drawings were lost. In 1923 he had contemplated the ruins of Berkeley following the fire that destroyed 584 homes. Nineteen of those houses he had designed and one of them was his own. The large scar contained the ruins of the landscape that he and his colleagues in the Hillside Club had worked to create. But the melancholic aspects of Maybeck’s vision may have been something else as well. Whenever it is mentioned, it is concerned with redwoods and to one who loved redwoods there was much to be melancholic about.

Despite his fascination with redwood groves, Maybeck the preservationist is not easy to locate. While the members of the Hillside Club, to which he belonged, wrote in “What the Club Advocates:” “The few native trees that have survived centuries of fire and flood lived because they had chosen the best places. They should be jealously preserved. Bend the road, divide the lots, place the houses to accommodate them!”6 And while Annie Maybeck was forever famous for forcing the city of Berkeley, on the spot, to divert a street around an oak tree,

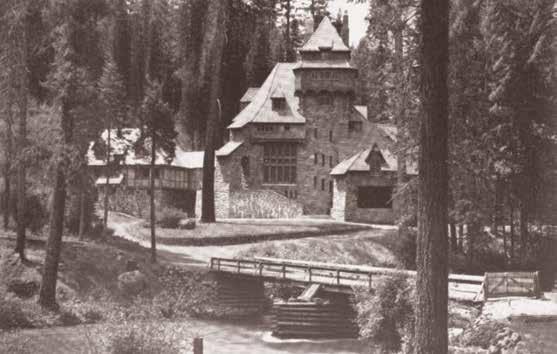

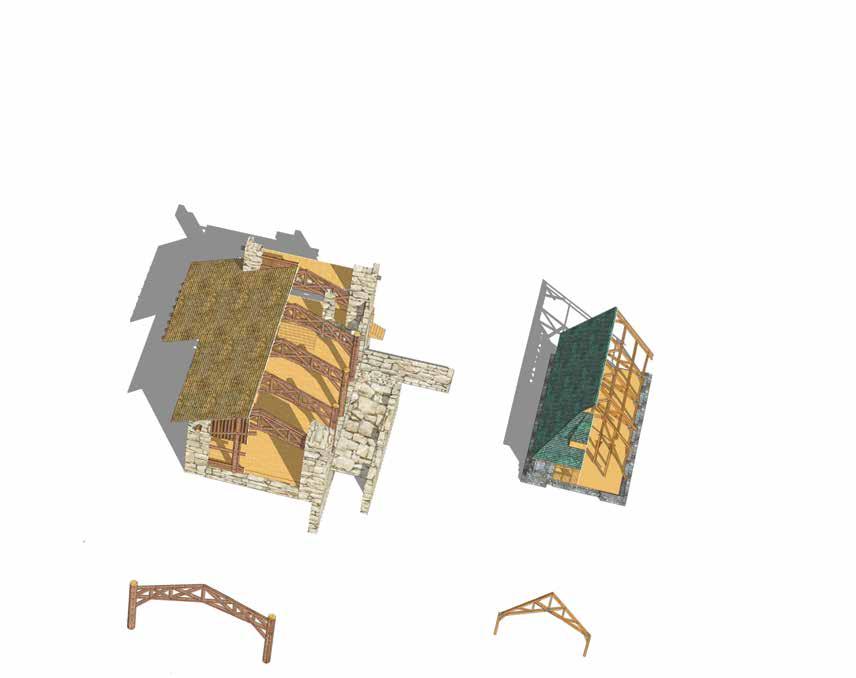

Maybeck’s tract “Hillside Building” speaks far more of preserving topography and how to plant new trees rather than saving existing ones. Many of his clients were preservationists, including members of organizations such as the Sierra Club, the Outdoor Art Club, and individuals such as Laura White, a vocal redwood preservationist. At the same time his clients and colleagues in organizations like the Bohemian Club included lumbermen and in time he did buildings for them, from exhibition buildings to lumber mill towns. The vision of a of redwood grove as a point of departure might not seem the obvious point to explain the Palace of Fine Arts but it is even less so for another work he describes in the same way, Wyntoon. This was a large castle for Phoebe Hearst located in a forest on the McCloud river in Northern California built in 1903. Steeply pitched tile roofs were supported by thick stone walls to form a pyramidal composition. The roof and floors were wood framed and the inner face of the roof deck was faced with bark. It had no columns to speak of, but in describing the work, Maybeck began with the description of a forest:

The idea of composing this construction in the primeval forest on the McCloud River resulted from several causes. First, the six trees in a semicircle. Second, the immense size of these trees. Third, the distance from railroad and expense of transportation. Fourth, climate. Fifth, forest fires. Similar conditions existed in the Middle Ages, and, consequently, without effort, the Gothic composition resulted.7

Wyntoon’s massive stone walls did not save it from what must have seemed something of a curse to Maybeck. It burned in 1929.

Wood had a special significance for Maybeck. Speaking at the dedication of a building he designed for lumbermen at the Panama Pacific Exhibition he said that: “genuineness can best be carried out in wood finish. ... rather than to use the sham of plaster, the monotony of which becomes so tiresome, while in the natural wood finish, figuration and beauty of grain gives rest to the eye in its endless variety.”8 But redwood had an importance went beyond color, texture, and grain.

Work began immediately on an extension to the Glacier Park Lodge, far less classical and far more Swiss than the original. It was a harbinger of what was to come, another side of Louis Hill was simultaneously at work on the other side of the park.

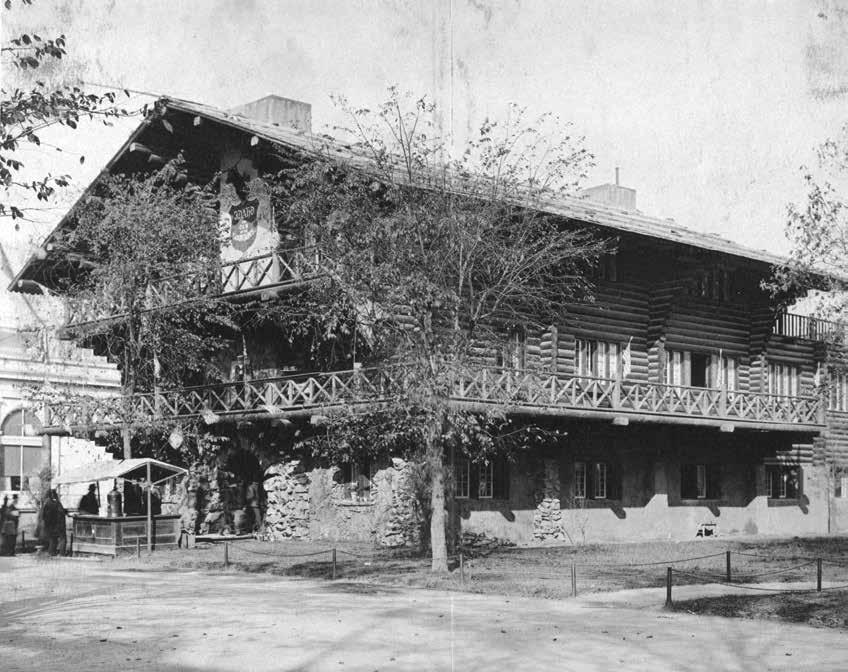

Two years before work began on the Glacier Park Lodge, 50 miles to the west, in Belton on the western edge of Glacier National Park, Louis Hill completed a house for his family, a chalet. This was about the time he announced he was moving to Montana. In a way Hill did move to Montana, though not as dramatically as he implied, spending his summers there. But in any case he did not stay long at the Belton Chalet and it became one of his many hotels. Hill was clearly more engaged with his chalets than the typical Adirondack millionaire. There was the Louis Hill who had become president of the Great Northern in 1907 that had pursued his role with enthusiasm and purpose, and when the occasion demanded could be no less ruthless than his father, the one who built the Glacier Park Lodge. This was the other side of Louis Hill—the avid fisherman, the passionate hunter, the dedicated landscape painter, the lover of the wilderness trek, the one who wanted to escape from an overcivilized world, who wanted to

move to Montana and live in a chalet, who wished to escape from his real life to a place of nostalgic imaginary origins. Perhaps these were fragments of a larger “other,” the other life he might have led, the other person he might have become.

Hill looked at chalet architecture in depth. He wrote to a St. Paul bookshop asking for the best volumes on the subject and obtained Gladbach’s and Varin’s encyclopedic and highly technical works.11 But his interpretation of what he saw could be quite shallow, and often so was the architecture, consisting of a thin layer of motifs rather than integral form. It was a language of association in which ornaments overlaid a construction, in which a correspondence of structural representation and structural reality was often absent. The chalet did not manifest the values associated with it; it simply represented them.

The two Louis Hills produced two architectures, on the eastern side of the park, the monumental gravitas of the giant forest of the Glacier Park Lodge. On the west the nostalgic, melancholic domesticity, the return to origins, of the Belton Chalet. The two were soon to appear simultaneously in the buildings that followed at Glacier.

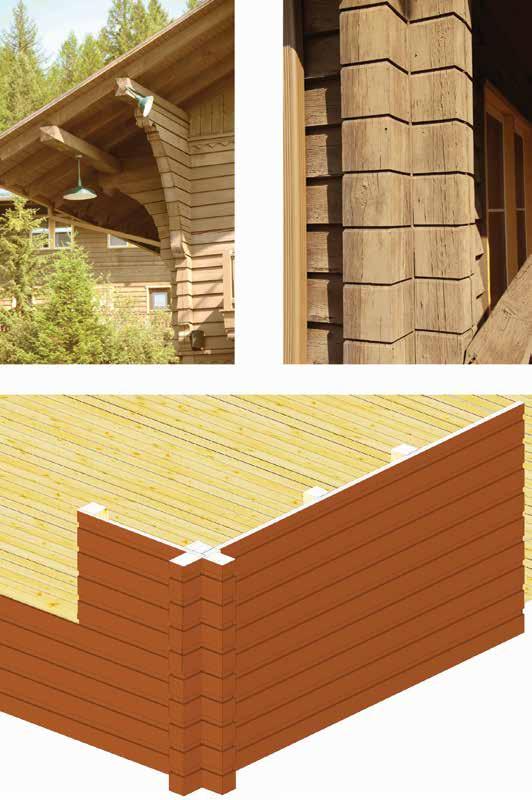

Cutter’s false-log corner detail North Point Camp Raquette Lake, NY

An example of Cutter’s false-log corner detail, also used at the Belton Chalet.

It is a severe misfit between image and reality, Making a wood stud wall with siding appear to be a Swiss type squared-log cabin. What appears to be overlapping and interlocking log ends is a single piece of timber.

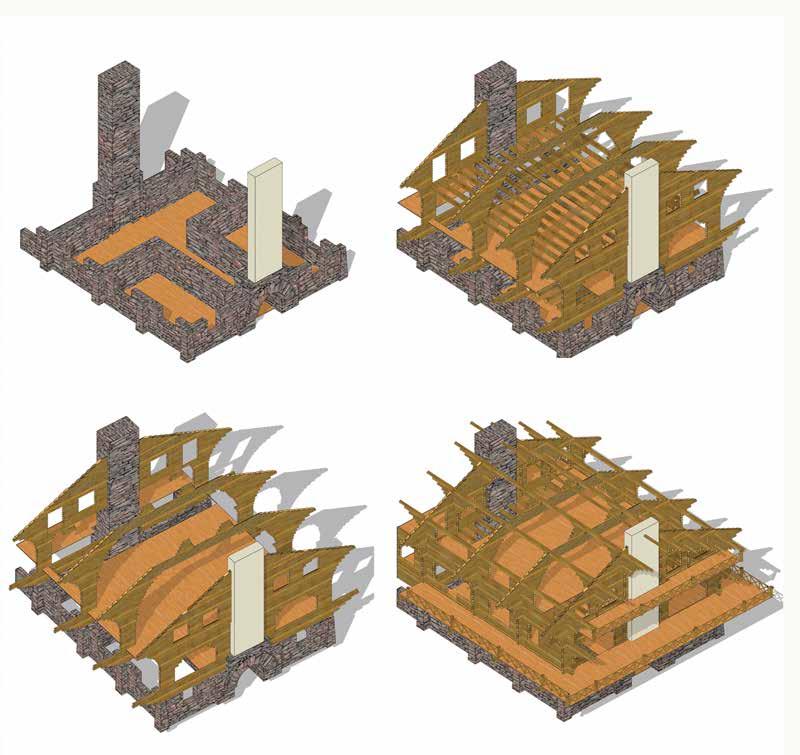

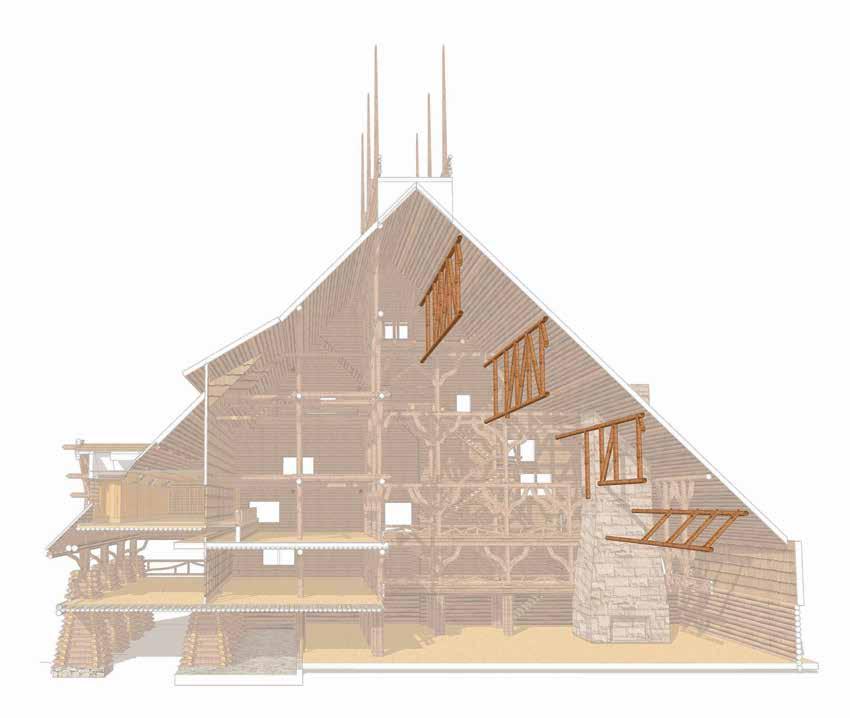

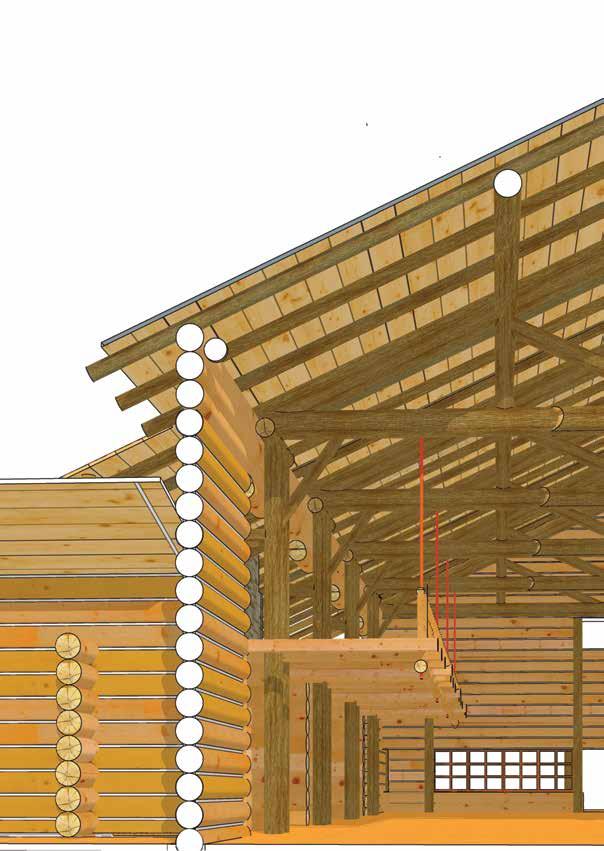

Kootenai lodge Wall Section at Suspended Balcony

The two sides of the hall are almost identical except for the suspended balcony over the fireplace.

The balcony is supported by1-1/2-inch rope or steel cables at each truss connecting to a 7-inch log beam log along the balcony edge supporting transverse beams. The tension rods shown as ropes on the original drawings, today the suspension rods are logs.

The decision to uses cables rather than columns to support the balcony seems more aesthetic than functional.

The shingles and boards of the roof are supported by 10-inch logs spaced at 3 feet resting on wood trusses.

The wall construction is solid12 -inch logs wall with cement chinking that run between the cluster of four columns.

The log structural frame here breaks free of the enclosing log walls to be almost freestanding. Since the bark is left on the logs of the frame and the logs of the wall are peeled the two are easily distinguished.

The roof structure is boards on 3-inch pole rafters supported by the log truss with 8-inch log top chord, 12-inch log bottom chord and 8-inch vertical with 1-1/2-inch round steel reinforcing cable inside.

Each end of the trusses is supported by a pier composed of a cluster of four 12-inch round log columns.

The 12-inch peeled log wall runs between the 4 logs of the column.

Let us return to a story we have passed over, Hopi House. Central to the creation of the village at the south rim of the Grand Canyon in the early years was the Fred Harvey Company. They built hotels and provided services like other railroad concessionaires but unlike other concessionaires they sold Native American art in quantity, and their role was not confined to marketing. They sold it, they commissioned it, they arranged special tours for tourists to purchase it. They arranged Native American performances as well, particularly dances, to publicize it. Architecture, obviously, was a key component of this enterprise.

The Harvey Company’s Native American program had begun with exhibits of Hopi crafts and craftsmen at world’s fairs, such as Chicago (1893). But as the Santa Fe moved west the market grew exponentially. Its first two large museum/ gift shops were the Albuquerque Indian Building-part museum, part curio shop, and, directly connected to the Albuquerque Santa Fe station and Hopi House at the Grand Canyon, that followed soon after. Both had the same intent and the same architectural concept, marketing Native American art from multiple nations, Hopi pottery, Navajo (Diné) rugs and jewelry. Even art from the Pacific Northwest was thrown in.

Charles F. Whittlesey was the architect of record of Hopi House. It owes a great deal to Henry Voth, a missionary who had lived with the Hopi for 10 years. Voth consulted on the design of Hopi House, which is modeled on the Hopi village at Oraibi.

Voth had done much that angered the Hopi. He published precise descriptions of their religious ceremonies and folklore, often obtained by forced entry to private ceremonies where he was forbidden. Voth crossed a boundary by appropriating these ceremonies as marketing devices for the Harvey Company. Voth is responsible for the most controversial part of Hopi House, two altars built in a room on the second floor, including a fourfoot-high door with leather hinges brought from Oraibi. To the Hopi then, and to many today, he was a thief, less of objects than of their essence.

Hopi House draws on images of indigenous architecture, not geology or the qualities of local stone. Later Harvey buildings were built of the local Kaibab limestone. In fact, what one sees is not the local stone. The whitish limestone from the site is used in the inner structural wall, but what one sees is the exterior facing, a redder Moenkopi Coconino Sandstone brought from Winslow, 150 miles away, undoubtedly by rail.

underwood's long Span Buildings

There will be many who feel this text is an unnecessary journey into subjects of peripheral importance. The value of the classic rustic American buildings is evident to the eye. Knowledge of who built them or why does not change their serene presence in the forest or desert. The Western landscape, particularly the parks, is essential to who we are, and so is the architecture it produced. Likewise, whatever unpleasant modern technical realities lie hidden below their rustic craft exteriors are not visible and not important. This text examines in detail thirty rustic buildings. Excepting single-family houses, thirteen were hotels and hotel buildings that were built directly or indirectly by the railroads. Four were built to promote the timber industry as advertising. Four were built by the Harvey Company to sell items to tourists. Eight were built by the Park Service for ranger stations or museums. Whatever the experiences these buildings sought to provide, whatever values the sought to embody—a life closer to nature, an existence less industrialized, a non-urban life in a minimal shelter—whatever self-reliant craft was employed, whatever Indigenous traditions were used, whatever Native cultures were emulated, were all things the railroads were in the process of destroying. The railroads committed simultaneous, contradictory acts of preservation and destruction, saving fragments of wilderness as part of a process that required the obliteration of the greater part of that wilderness through timber harvesting and mining. The creation of rustic buildings was no less contradictory, importing industrial technologies to create an

architectural imagery of the Indigenous architecture it was destroying.

A short evaluation would be that both the experience and the architecture were a sham. A two-week visit to one of the parks and hotels was not really a rustic experience and neither was the architecture. Both provided the illusion of a connection to nature and a disconnection from culture, and since it was all a performance, the architecture was only a stage set for playing at being rustic—an industrial fabrication with no more authenticity than a canvas backdrop at the opera. It was an all too appropriate veneered container for a veneered life—steel-framed kivas, half-log faced cabins, faux-Indigenous symbols. All were advertising, a marketing tool built by the railroads to financially support the railroad. The Indigenous architecture was commodified and mass marketed, a small part of the larger commodification of the landscape. The establishment of the Park Service in 1916 created a situation that was strangely similar. They were doing marketing in their own way, they simply measured profit in number of visitors, and if Hopi Pueblos could be commodified for the purpose, so could log cabins.

But it is not so simple. There were authentic experiences. There were authentic buildings and there was some truly great architecture that can stand alone outside the tainted history if its creation.

I will close with one more story of a wilderness experience and since I began with Horace Kephart’s, I will end it with Philip Johnson’s.