ANNAMARIA MAURO

Direttrice dei Musei nazionali di Matera

Director of the National Museums of

Matera

INTRODUZIONE

INTRODUCTION

Un tempo passato, lontano dal nostro presente, rivive in chiave contemporanea grazie alla fotografia di Luigi Spina e a nuovi punti di vista e prospettive.

I vasi italioti a figure rosse della Magna Grecia e della Collezione Rizzon, conservati nei Musei nazionali di Matera, nella sede del Museo Ridola, offrono l’occasione per percepire il mondo antico con occhi nuovi e per scoprire i suoi significati più reconditi.

Importante testimonianza della pittura vascolare e del lavoro dei più noti ceramisti tra il V e il IV secolo a.C., i vasi a figure rosse rappresentano certamente una risorsa imprescindibile per lo studio della ceramica, ma sono anche fonte inesauribile di conoscenza sulla vita, sugli usi e sui costumi di una società che, se osservata dalla giusta angolazione, incarna valori non così lontani da quelli che dovrebbero governare una società moderna.

I vasi a figure rosse della collezione magnogreca, molti dei quali risalenti alle scoperte di Domenico Ridola, sono parte integrante di complessi corredi funerari, unendo così al valore puramente stilistico ed estetico anche un forte valore simbolico e di rappresentanza della vita del defunto. Molto spesso, infatti, le scene figurate si ricollegavano a determinati aspetti che avevano caratterizzato quella persona, oppure questo avveniva mediante episodi e personaggi del mito.

La Collezione Rizzon, invece, costituita da settantaquattro vasi apuli e lucani acquisiti dallo Stato nel 1990, se da un lato risulta priva del suo contesto originario, proprio perché proveniente da una collezione privata, dall’altro è un vero e proprio atlante di scene figurate e di

Offering fresh vantage points and new perspectives, Luigi Spina’s photography brings to life a past that is far removed from the present day, presenting it in a contemporary key.

The Italiote red-figure pottery from Magna Graecia and the Rizzon Collection, housed in the National Museums of Matera’s Ridola Museum, offers an opportunity to perceive the ancient world with new eyes and to tease out its innermost meanings.

As an important example of pottery painting and the work of the most famous potters between the fifth and fourth centuries BC, this red-figure pottery is undoubtedly an indispensable resource in the study of ceramics. At the same time, it is also an inexhaustible source of clues about the life, customs, and traditions of a society which, if viewed correctly, embodied values not so far removed from those that ought to govern a modern society.

Much of the red-figure pottery in the Magna Graecia collection formed part of the funerary goods discovered by Domenico Ridola. These pieces combine purely stylistic and aesthetic merit with strong symbolic values and important representations of the lives of the deceased. Indeed, the scenes often directly depict specific themes that typified a person’s life, or else portray episodes and characters taken from myth associated with the deceased by analogy.

However, although the Rizzon Collection, consisting of seventy-four pieces of Apulian and Lucanian pottery acquired by the State in 1990, is divorced from its original context, precisely because it comes from a private

decorazioni opera dei più noti pittori del tempo, come il Pittore di Dario, il Pittore di Dolone, il Pittore di Pisticci.

Da una prospettiva estetica e visiva, il contrasto di colori che questi oggetti offrono, tra il nero della “vernice” che fa da sfondo alle scene e che delinea volti e dettagli e il rosso della terracotta delle figure che si esalta con la cottura dell’argilla, viene accentuato attraverso le luci e le ombre che la fotografia può creare mediante una serie di espedienti.

La luce, dalle diverse angolazioni con le quali può sfiorare la superficie della ceramica, ci consente di leggere in maniera diversificata l’apparato iconografico di un vaso: possiamo osservare come gli sguardi dei personaggi si incrocino tra di loro o come cadano su un determinato dettaglio, ma possiamo anche solo soffermarci a osservare la maestria del pittore nel creare una fitta rete decorativa costituita da figure, oggetti di varia tipologia, elementi architettonici e vegetali.

E se la stimolazione sensoriale, attraverso la vista, è il mezzo migliore per raggiungere le memorie più antiche e ancestrali che albergano in ognuno di noi, l’uso della fotografia rappresenta allora il percorso più adatto a questo scopo.

È un volume in cui il nero è protagonista. La centralità è data alle figure, ai dettagli. L’emergere delle raffigurazioni color terracotta dal fondo nero del vaso è messo in risalto dallo sguardo ravvicinato della macchina fotografica di Luigi Spina. I particolari anatomici, i panneggi dei tessuti sono proposti all’occhio senza il filtro del vetro museale, annullando la distanza sia spaziale sia temporale. I dettagli bianchi e color porpora arricchiscono la bicromia dei vasi, restituendoci una vivacità cromatica e di texture apprezzabile da vicino. Fotografare un oggetto d’arte vuol dire coglierne il significato intrinseco e comunicarlo al mondo esterno. Questo è alla base del progetto fotografico che Luigi Spina ha ideato per una selezione di vasi a figure rosse dei Musei nazionali di Matera. Lontano dal concetto di catalogo classico, si tratta di un atlante visivo di forme e linee, dove il nero esalta il rosso della terracotta e delle figure. Attraverso il linguaggio della fotografia, in un costante rapporto di distanza e vicinanza, si crea così un racconto per immagini unico e continuo, in cui la figura e la scena restano centrali.

collection, it is nonetheless a real treasure trove of narrative scenes and decorations by the most famous painters of the time, such as the Darius Painter, the Dolone Painter, and the Pisticci Painter.

From an aesthetic and visual point of view, the colour contrast in these objects – between the black backgrounds of the scenes, against which faces and details are picked out, and the red clay of the figures, further enhanced by the firing process – is accentuated through the light and shade that photography can create through various techniques.

The angle at which the light strikes the surface of a vase can help us to read the subtle communication of its iconography: we can observe how the gazes of the figures meet or how they focus on a particular detail, or we can also just pause to admire the painter’s skill in creating an elaborate decorative scheme made up of figures, various types of objects, architectural details, and plant motifs.

And since sensory stimulation, through sight, is the best means of reaching the most ancient and deepest memories that dwell within each of us, then photography is the most suitable route to this end.

This is a book in which black plays the leading role. Human figures and details predominate. The way terracotta-coloured subjects emerge from the black background of a ceramic object is emphasised by Luigi Spina’s close-ups shots. The anatomical details and the folds of the fabrics are presented without the distraction of the glass of the display case – eliminating both spatial and temporal distance. The white and purple details leap out of the two-tone colouring of the pottery, giving us a chromatic and textural richness that can be fully appreciated up close.

Photographing an art object means capturing its intrinsic meaning and communicating it to the outside world. This is at the heart of Luigi Spina’s photographic approach to the selection of red-figure pottery of the National Museums of Matera. Far from being a standard catalogue, this is a visual atlas of shapes and lines, where black enhances the red of the terracotta and figures. Photography thus uses images in a constant interplay between distance and proximity to create a unique and continuous narrative, in which the figure and the scene remain central.

CLAUDE POUZADOUX

Professore ordinario di Storia dell’arte e Archeologia pre-romana e romana, Università Paris Nanterre Professor of Art History and Pre-Roman and Roman Archaeology, University Paris Nanterre

UN INVITO A GUARDARE:

IL VASAIO, IL PITTORE

E IL FOTOGRAFO

Con il suo obiettivo puntato sui vasi a figure rosse del Museo Ridola di Matera, Luigi Spina non ha trovato soltanto un nuovo modo di fotografarli: ha inventato un modo di guardarli. Mentre rivelano la lucentezza del nero, le sue foto ci invitano a riscoprire l’ingegnosità dei pittori che, nell’Atene della fine del VI secolo a.C., idearono una nuova tecnica per decorare i vasi passando dal nero su fondo rosso al rosso su fondo nero. Questo cambiamento diede libero sfogo alla flessuosità dei corpi, a una decorazione più ricca, così come al movimento delle figure e all’animazione delle immagini. Per oltre un secolo i pittori italioti della Magna Grecia hanno magistralmente messo questa tecnica al servizio dell’illusione pittorica sfruttando la gamma della tetracromia: quattro colori naturali sono stati sufficienti ai ceramografi per arricchire i loro vasi di motivi vegetali e dipingere scene della vita quotidiana o di racconti mitologici. Dalla stessa argilla ferruginosa, accuratamente selezionata e utilizzata dal vasaio per modellare il suo vaso, il pittore conservava la parte più depurata per ottenere, grazie all’altissima temperatura di 950 °C, il nero per ricoprire le superfici e disegnare i contorni; le figure non rivestite mantenevano il colore rosso che l’argilla assumeva a causa dell’ossidazione delle particelle fini di ferro, trasformate in ematite durante il processo di cottura a una temperatura inferiore; il bianco era fornito da argilla caolinica, sul quale il pittore poteva stendere un sottile strato di ingobbio (N.d.R.: la ricopertura a base di argilla finissima che riveste il corpo ceramico, sulla quale veniva dipinta la decorazione) diluito per ottenere del giallo.

AN INVITATION TO LOOK: THE POTTER, THE PAINTER, AND THE PHOTOGRAPHER

By training his lens on the red-figure pottery in the Ridola Museum, Luigi Spina has not only found a new way of photographing the vases: he has invented a way of really looking at them. While certainly revealing the brilliance of the black, his photos also invite us to rediscover the ingenuity of the painters who, in late sixth-century BC Athens, devised a new technique for decorating vases, going from black on a red background to red on a black background. The changed perspective made it possible to concentrate on the suppleness of the bodies, to develop elaborate decorations, and to enhance the movement of the figures as well as the liveliness of the scenes. For more than a century, the south Italian painters of Magna Graecia masterfully applied this technique to create painterly illusions, exploiting the full potential of tetrachromy: four natural colours were all they needed to decorate their vessels with plant motifs and scenes of everyday life or mythological tales. The painter set aside the very finest of the carefully selected ferruginous clay the potter used to shape his vase to obtain the black needed to coat the surface and draw the outlines of his figures, thanks to the extremely high firing temperature of 950°C. Uncoated figures took on the red hue that the clay acquired through the oxidation of fine particles of iron, which were turned into haematite by lower-temperature firing phases; white was obtained by using kaolin, over which the painter could add a thin layer of diluted slip (a creamy mixture of clay and water, used especially when decorating earthenware) to achieve yellow. But it was the artist’s job to create harmonious compositions.

Ma spettava soprattutto alla bravura del ceramografo il compito di disporre le forme in modo armonioso. Seguendo linee e contorni, l’occhio di Luigi Spina ci invita a sua volta a seguire questa sottile linea nera per ammirare i personaggi e i dettagli che emergono dalle sue inaspettate inquadrature.

LA LUCENTEZZA DEL NERO

Il primo risultato ottenuto dal fotografo è quello di aver saputo sfruttare le qualità riflettenti dell’ingobbio argilloso, vetrificato per effetto della cottura in atmosfera riducente, per disegnare con la luce il profilo concavo o convesso delle diverse parti dei vasi. Come in una dissolvenza incrociata il nero opaco dello sfondo svanisce sotto le luci per lasciare posto a una superficie di un nero brillante. Il nero esce dal nero. Chi osserva la collezione scopre così numerose forme destinate a svariati usi: i diversi tipi di cratere – a calice, a volute, a colonnette, a campana – utilizzati per mescolare il vino con l’acqua; la situla, legata anch’essa al consumo del vino; l’hydria, la pelike e la loutrophoros, che servivano per il trasporto dell’acqua, l’anfora per quello del vino; e il lebes gamikos, legato ai riti del matrimonio. Nelle immagini, la messa a fuoco sul primo piano ci permette di apprezzare in pieno la capacità di disegnare sulle superfici curve di questi vasi. Pagina dopo pagina l’occhio, come in una sequenza cinematografica, fa ruotare i vasi su loro stessi e scopre gli schemi e la ricca gamma di elementi decorativi con i quali i pittori hanno strutturato, con maggiore o minore abilità, le scene rappresentate in funzione delle forme: fregi con animali (pantere, leoni, cinghiali) ornano l’orlo dei crateri a colonnette, con il collo decorato da foglie d’edera e corimbi, mentre una fila di linguette adorna le spalle e doppie file verticali di puntini, affiancate da linee sottili, incorniciano la scena dipinta sulla pancia del vaso (si veda il cratere a colonnette del Pittore di Wolfenbüttel). Con lo sviluppo del cosiddetto stile “ornato” da parte del Pittore dell’Ilioupersis (370-360 a.C. circa), dei raggi neri disposti a raggiera compaiono tutt’intorno all’attacco delle anse dei crateri a campana, delle hydrie e delle anfore di tipo panatenaico, il cui collo slanciato è marcato da una fascia di lunghe linguette nere, sotto una linea a zigzag e una palmetta alla sommità (come nell’anfora del Pittore di Graz).

Luigi Spina’s eye in turn invites us to follow this thin black line to see how the figures and details emerge in his startlingly framed shots.

THE BRILLIANCE OF BLACK

The photographer’s first feat was to exploit the reflective qualities of the clay slip, vitrified under the effect of firing in a reduced atmosphere, so as to use light to emphasize the concave or convex profiles of the different parts of the vessels. As in a cross-fade, the matt black of the background fades under the beam of the spotlight, giving way to a glossy black volume. Black emerges from black. In this way, the viewer becomes acquainted with a number of different types of vessels in the collection – each designed for a specific purpose: the various calyx, volute, column, or bell kraters for mixing wine and water; the situla, also used for serving wine; the hydria, pelike, and loutrophoros for holding water, and the amphora for transporting wine; as well as the lebes gamikos, which was used during wedding ceremonies. Focusing on the foreground enables the viewer to admire the unerring skill displayed in depicting figures on the curved surfaces of these vessels.

As the pages turn, so the eye, like a movie camera, traverses over the surface of the vessels and discovers the sketches and the rich decorative grammar the painters employed to depict the scenes that unfold to match the forms, sometimes a little clumsily: friezes depicting animals (panthers, lions, wild boars) adorn the rim of column kraters, their necks girdled with ivy leaves and corymbs, while little tongues adorn their shoulders and a vertical row of dots flanked by fine lines frames the body’s central scene on either side (see the specimen by the Wolfenbüttel Painter). With the development of the ornate style by the Ilioupersis Painter around 370–360 BC, black rays appear at the base of the handles of bellshaped craters, hydrias, and panathenaic amphorae, whose slender necks are emphasised by long black tongues under a zigzag line and crowned by a palmette (as in the amphora by the Graz Painter).

Leafing through the book, there is also plenty to admire in the work of the painters. For example, we come across a narrow meander cunningly concealed behind lateral palmettes, thus confining a frieze (for example in the pelike by

5 CONTINENTS EDITIONS

Caporedattore |

Editor-in-Chief

Aldo Carioli

Progetto grafico e impaginazione |

Art Direction and Layout

Stefano Montagnana

Redazione | Editing

Charles Gute, Lucia Moretti

Traduzione dall’italiano all’inglese | Translation from Italian to English

Julian Comoy

Fotolito | Pre-press

Maurizio Brivio, Milano

Tutti i diritti riservati | All rights reserved

© Per le immagini | For the images: Luigi Spina

© Per i testi | For the texts: Annamaria Mauro, Claude Pouzadoux, Adriana Sciacovelli, Luigi Spina

Per la presente edizione | For the present edition

© 2024 – 5 Continents Editions, Milano

È vietata la riproduzione o duplicazione di qualsiasi parte di questo libro, con qualsiasi mezzo. | No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

5 Continents Editions

Piazza Caiazzo 1 20124 Milano

www.fivecontinentseditions.com

ISBN: 979-12-5460-029-0

Distribuito in Italia e Canton Ticino da Messaggerie Libri S.p.A. | Distributed in Italy and Switzerland by Messaggerie Libri S.p.A. Distributed by ACC Art Books (UK, USA) throughout the world, excluding Italy.

Finito di stampare nel mese di giugno 2024 su carta Sappi Magno Satin presso Tecnostampa –Pigini Group Printing Division Loreto – Trevi, Italia, per conto di 5 Continents Editions, Milano | Printed on Sappi Magno Satin paper and bound in Italy in June 2024 by Tecnostampa – Pigini Group Printing Division Loreto – Trevi for 5 Continents Editions

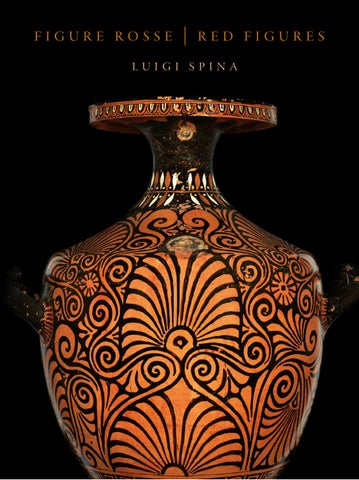

Copertina: Hydria, Pittore di Baltimora (325-320 a.C.), Collezione Rizzon

Cover: Hydria, Baltimore Painter (325–320 BC), Rizzon Collection

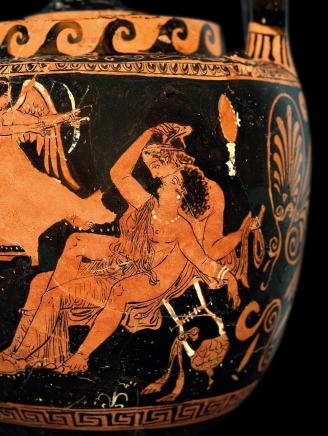

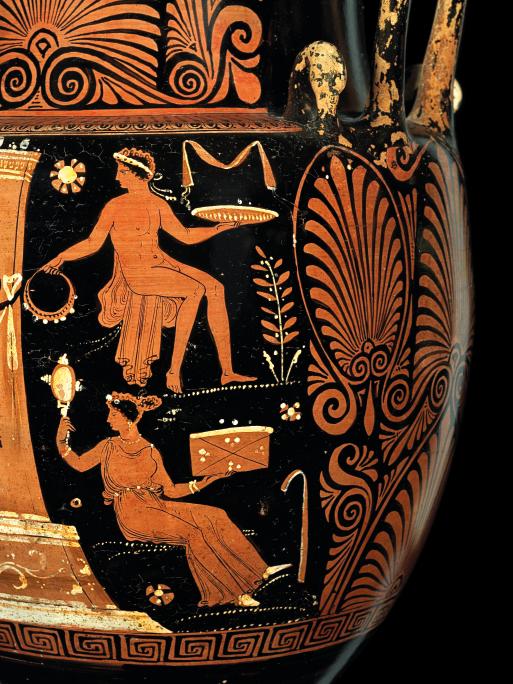

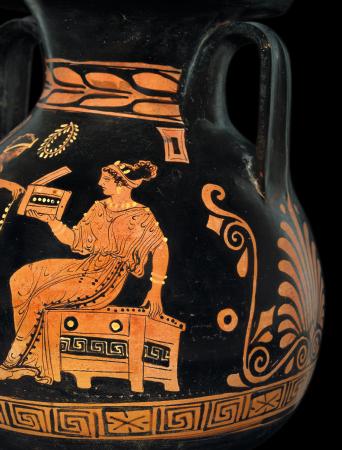

Pagina 2: Cratere a campana (particolare), Pittore di Ruvo 512 (360-340 a.C.), Collezione Rizzon

Page 2: Bell Krater (detail), Painter of Ruvo 512 (360–340 BC), Rizzon Collection

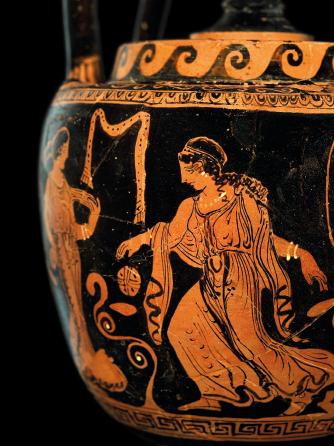

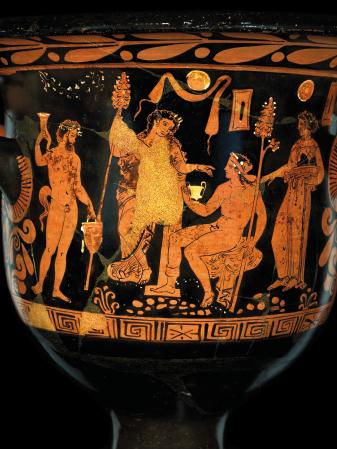

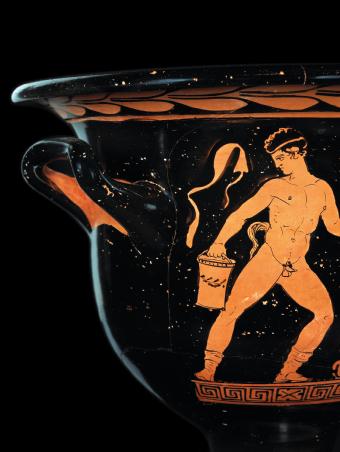

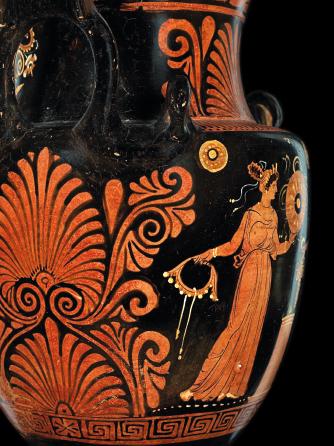

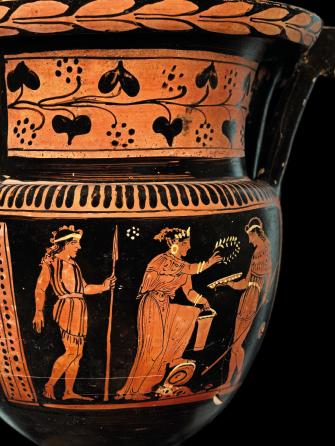

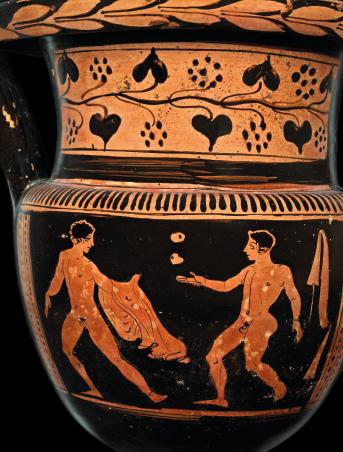

Pagine 3, 4: Cratere a campana (particolari), Pittore di Amykos (425-400 a.C.), Collezione Rizzon

Pages 3, 4: Bell Krater (details), Amykos Painter (425–400 BC), Rizzon Collection