ORO Editions

There’s no sugar coating this: we are living amid an accelerating climate emergency, and urgent change is needed to stave off an environmental and societal catastrophe. Building operations and construction collectively contribute 40% toward global carbon dioxide emissions,9 making the built environment one of the major contributors to climate change. Today, architects need to step up to make transformative changes to the industry and profession to decarbonize the built environment as quickly

as possible, or else settle for the status quo and make future generations cope with the aftermath.

///

Put another way, we need to approach design prompts as ones that prioritize living systems: spaces that prioritize stability and longevity, durability, and human health. Spaces that enhance ecologies and living systems, and bring communities together. A human-centered response to the climate emergency can yield a spectrum of creative and crucial strategies, all focused on fostering the well-being of communities into an uncertain future.

///

We’ve learned that we must be nimble and flexible with how to respond to climate change. As the industry catches up to prevailing research, we are working to adapt our own practice’s approach to climate action. For example, within the last decade, we have completely pivoted our focus to carbon—including embodied carbon—rather than designing solely to optimize operational energy efficiency or energy cost savings. We have learned to communicate the urgency of moving away from fossil fuels and step up our projects’ on-site energy storage capacities. We are connecting the dots between the

industry’s reliance on fossil fuels, the dangers of gas appliances installed in buildings in wildfire-prone regions, and equity issues in the supply chain. The next ten years may yield yet more revolutions in our practice, as we are ready to anticipate an increasingly strained energy grid, the promise ( and the challenges ) with electric vehicle movement, the market availability of lowembodied carbon technology, and adjusting to expectations for a post-COVID society.

///

We have hope. Architects have been committed to a zero-carbon future for decades. The following strategies can serve as guideposts on the journey toward a zerocarbon practice:

/// BUILDING

Adaptation is a strategy that can yield immense carbon savings, but it’s not always easy to find a client who is willing to transform an existing building into a space of their own. Being at the table for early scoping decisions, such as site selection or existing building assessments, can create visioning opportunities and open possibilities in surprising ways. (See the Adaptation chapter in this book for more on this topic. )

weaves innovative educational spaces into the land, creating places that foster community, lifelong learning, and environmental stewardship. The 38,600-square-foot complex integrates advanced resource efficiency, carbon reduction, and immersion in the natural world, coalescing design responses to program, site, and the biosphere. Spanning seventeen years, the multiphase project documents the evolution of the school’s environmental mission as well as the broader advancement of best practices in sustainable design.

The Nueva School is an independent school serving more than five hundred students from prekindergarten through the eighth grade. The school’s mission is to inspire passion for lifelong learning, foster social acuity, and develop the child’s imaginative mind, enabling students to learn how to make decisions that will benefit the world. The thirty-three-acre campus, located in the semirural coastal hills of the San Francisco Peninsula, features a thriving coast, a live oak woodland ecosystem, a variety of dispersed structures, and dramatic views of San Francisco Bay. The site, a gentle down-sloping ridge, was formerly a parking lot on a campus with a soccer field and various buildings.

The 27,000-square-foot first phase of the project, completed in 2007, created a flexible new Classroom Building, a Library, and a Student Center that support the school’s evolving vision of educational innovation and environmental stewardship. Phase two, completed in 2021, expanded the Student Center and created a new, zero-carbon, 11,600-square-foot

Science and Environmental Center to focus the school’s curriculum even more intensely upon environmental citizenship. An accessible, elevated canopy walk links the Student and Science centers and hovers above a restored live oak woodland. The completed complex integrates a wide range of design responses to program, site, and biosphere, supporting the school’s mission by immersing students in the experience of their hillside environment.

The four buildings are carefully woven into the site’s topography and ecology, oriented to the mild climate to optimize the benefits of outdoor learning, daylighting, and natural ventilation. They cluster around an existing ridge and step with the natural slope. This reduces excavation while it links students to the drama of the hillside and views beyond. Living roofs on the Library and Student Center support biodiversity by creating 10,000 square feet of new habitat for native bird and butterfly species, including the endangered Myrtle’s Silverspot Butterfly.

The project stitches together the existing campus to foster community and creative interaction at many scales. The Plaza serves as a new entry to the school, an outdoor classroom, and a community gathering space. The Student Center is both cafeteria and band shell that opens to an amphitheater in warm weather. The Science and Environmental Center serves as a physical gateway to a nature preserve downhill from campus. A variety of intimate indoor and outdoor spaces encourage informal gatherings and quiet study.

The buildings promote personal inquiry and discovery by visibly telling their story—how they resist gravity and earthquakes, breathe, absorb solar energy, distribute information, and respond to the seasons. Strategically placed “X-ray” windows expose glimpses of pipes, conduits, and structure within the walls. The project models environmental stewardship at many levels, establishing visible connections between students and the natural world around them. Through a variety of simple, integrated design strategies including natural ventilation, earth sheltering, daylighting, and efficient building systems, phase one of the project uses 69% less energy and 50% less water than a typical US school of its size. Phase two uses 70% less water and is zero carbon, as it receives all of its required energy from a rooftop solar array. The evolution of the Nueva School Hillside Learning Complex has successfully supported the school’s growing environmental mission, introducing students and their families to new ways of living with the natural world.

No other large building in the city has such an eco-friendly flourish as the solar cloak, and the effect is striking.

I feel a great sense of gratitude. I feel safe, and I feel tranquil in my apartment. And I absolutely love this garden.

This is a great place, a really great place to be. It’s safe, it gives you peace of mind and security. It also makes you feel comfortable because you’re around people willing to help you if you need help.

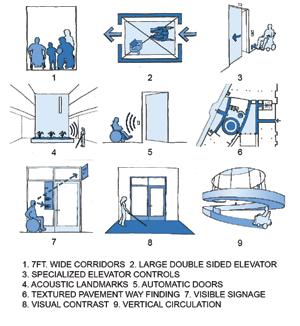

AN EMBRACING CIVIC PLAZA and a transparent facade welcome people of all abilities.

CENTRAL ATRIUM SPACE illustrates several Universal Design strategies: looped circulation provides clear wayfinding; splayed walls, and an absorptive ceiling calm the acoustical environment; a fountain at the north end provides a calming, biophilic acoustical landmark.

The design of the ERC began with a series of lively workshops drawing upon experts within the disability community as well as leading disabled access consultants. Our task was to design for the broadest possible range of disabilities—including mobility, dexterity, sight, hearing, chemical sensitivity, and cognitive disabilities—with the active participation of representatives from all constituencies.

To facilitate clear communication and efficient discussion, we broke the larger idea of universal design into six categories of environments: physical (building approach, arrival, organization, movement, and life safety), visual (daylighting, artificial lighting and controls,

and visual and acoustical way-finding), acoustical (acoustical control, privacy, and clarity for people with hearing disabilities), thermal (natural ventilation, filtered outdoor air, localized control, and digital control), electronic (security, digital access, and flexible communications technologies), and chemical (healthy indoor air quality, nontoxic materials, and smoke and fragrance-free indoor air quality). We discussed and resolved each of these categories in detail with the various user groups, documenting the final decisions in a detailed universal design memo. This allowed us to clearly define the final universal design elements of the project for the client and the broader community.

These workshops not only provided invaluable information about appropriate design solutions, but also offered transformative insights into communication methods. When presenting designs to people without vision, we must quickly adapt to better methods of communicating. We learned to explain our ideas more clearly and in greater detail. We developed two types of physical models—a typical detailed model and a solid tactile model that could be passed around the room to people with sight disabilities. We presented tactile floor plans printed on an embossing Braille printer, so that blind people could “tour” the building during the design phases

DESIGN WORKSHOPS helped ensure that the project met the needs of everyone. Here, former ERC President Dmitri Belser tests a long-range card reader that allows occupants to operate doors hands free.

UNIVERSAL DESIGN strategies can be incorporated within any project using standard materials and products at little or no additional cost.

After the building opened, we talked to residents about how the building was working for them. I’ll never forget the man who said he was proud to live in a building that passersby thought was for millionaires.

this highdensity, transit-oriented housing project transformed the site of an abandoned gas station near a busy freeway into a community asset for low- and very low-income seniors. More than half of Merritt Crossing’s seventy apartments are set aside for seniors who are unhoused or at risk of homelessness, living with HIV/AIDS, or challenged by mental illness. The building both meets the needs of this population and incorporates advanced universal and sustainable design strategies.

We arranged Merritt Crossing along the long edge of a corner site to reserve a twenty-foot side yard for a sunny, landscaped, courtyard garden. This configuration allows the courtyard to be directly linked to the building’s groundfloor entrance, community room, kitchen, and laundry. The area is designed as a series of outdoor spaces that move from public to more private activities. The high-ceilinged ground-floor rooms are encased in glass walls to enhance their connection to the courtyard and the public sidewalk.

To provide room for common and supportive spaces on the restricted site, we used stacked lifts to minimize the footprint of required on-site parking. We wrapped the garage with a living wall and tucked planting beds under the street side of the building to serve as storm water retention tanks. By reducing the visual impression of the ground floor, the upper floors appear to float above, lightening the building’s impact.

Merritt Crossing’s upper floors are organized into two parallel bands of apartments. These are separated by wide hallways with glazed ends that open

onto views and introduce daylight. Many of the apartments have balconies that are recessed into the building mass. On the south (red) facade, the alcoves help mitigate the visual and acoustic impact of the adjacent freeway while providing solar shading. A variety of openings and plant-supporting mesh panels provides a composition that can be read from the freeway. On the north (green) facade, the pattern of openings is compatible in scale and variety with the adjacent residential neighborhood. The building’s color scheme, inspired by the bold and bright colors found in the neighborhood, accentuates the separation between the two bars of apartments and between the outer building skin and the setback balconies and voids.

Integrated sustainable strategies provide healthy indoor environments for the senior residents and reduce long-term operating costs. A rooftop solar hot water systems provides 70% of the energy for domestic hot water, and a photovoltaic system supplies enough clean energy to power common area electrical needs. The project was certified under three independent third-party certification systems—LEED Platinum, GreenPoint Rated Platinum, and ENERGY STAR rating—and was the first multifamily housing project in California to receive the ENERGY STAR label. Merritt Crossing demonstrates the cumulative impact of reinforcing social, community, and sustainability goals.

After being homeless for many years, living with family, friends, on the streets and in shelters, I ran across a former counselor and friend. He asked me if I was still homeless. I said, “Yes.” He recommended that I apply for housing under a lottery for people fifty-five years and older. My prayers were answered, and my name hit the lottery for Merritt Crossing. At my first arrival, I ran across a few friends I knew when I was homeless, including one whom I used to sleep on the sidewalk with. I felt so happy for me and them that we are all living here. Being here at Merritt Crossing brought back memories of sleeping right under the very freeway I look at every day. The neighborhood and merchants have showed me much love and support. I met a lot of new friends here. I am now going to church, playing bingo, playing music, and having Monday coffee hour. It means a lot to me. It’s like having a new family.

denise harding , resident merritt crossing

denise harding , resident merritt crossing

innovative educational environments to inspire twenty-firstcentury high school students. Reflecting Nueva’s values as a “private school with public purpose,”22 these environments deploy economical and durable construction materials in new ways and offer replicable models for all schools. The design incorporates recent research into the spatial implications of learner-centered pedagogy, social and emotional learning, and design thinking. It is capable of nimble adaptation to evolving educational needs while supporting creative inquiry and nurturing mind-body wellness.

The program includes flexible classrooms and seminar spaces, innovative science laboratories and maker studios, a student café, a gymnasium, a student center, and a writing and research center. The 2.75-acre campus is located within a new transit-oriented development built on the site of a former horse-racing track. It offers a variety of outdoor spaces that extend the learning landscape and enhance daily connections to the community and the natural world. Incorporating a variety of ecological design strategies, the Nueva School is conceived as a living laboratory that inspires student research into low-carbon, resource-efficient learning and living.

We replaced the traditional model of the horizontal suburban high school with a dense, vertically stacked design better suited to the compact, semi-urban context. Program requirements that couldn’t be accommodated on site— including sports fields, an aquatic center, a research library, and a performing arts center—are served by nearby public

resources. This encourages students to engage with the surrounding city of San Mateo while it eliminates the space, cost, and energy required to build and maintain new facilities. The school, in turn, makes its gym and other event spaces available to the community.

We envisioned the learning environment as a city, a collection of buildings expanding from its core to the surrounding community, offering a rich diversity of neighborhoods and experiences. Like a city, the school is a layered, three-dimensional matrix that provides sectional variety, abundant open spaces, and maximum transparency to enhance interconnections and enrich social life. A plaza at the main entrance culminates a 1.5-acre public park to the south and has served as a community meeting place for an art festival, a farmers market, and a science fair. A variety of outdoor spaces—including contemplative study courts, active sport courts, maker spaces, rooftop patios, and a dining terrace—further enhance daily connections between students, their school community, and the natural world. Healthy nutrition, fitness, and social connection are celebrated at the hub of student life where the student café, a dance/fitness studio, and the student center cluster around a courtyard warmed by the morning sun.

Simple, costeffective strategies and systems demonstrate advanced resource efficiency and low-carbon living. We designed the school to reduce its energy use 65% from baseline, which exceeds the AIA 2030 Challenge. The building envelope utilizes standard materials and systems to achieve a performance 20% better than California’s Building Energy Efficiency Standards. Five threestory chimneys punctuate the north wing and provide fresh air and light at its center as well as views between floors. Instructional spaces are primarily naturally ventilated, augmented by ceiling fans in warm weather. Photovoltaic arrays provide nearly 20% of the school’s energy. Nueva School at Bay Meadows embodies the ideal of school as an ecology of learning. It supports the development of “creative, resilient, thoughtful leaders and collaborators who are ready to solve problems and have an impact on the world.”23

ROOFTOP TERRACE provides spaces for outdoor learning and urban farming.

SCHOOL’S PUBLIC FACE shows cantilevered photovoltaic array and sunshade elements.

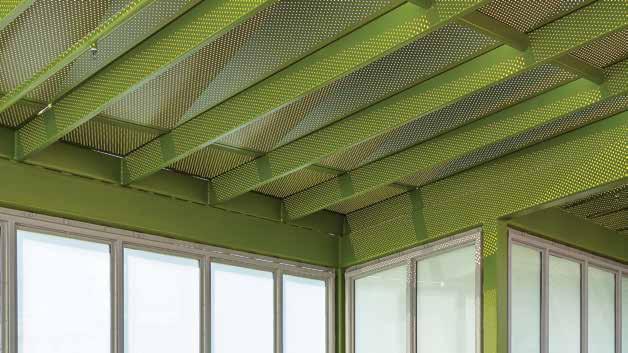

PERFORATED METAL ROOF lifts upward to redirect the wind and elongate the building’s wind shadow.

supports intellectual, social, and spiritual education at the core of a 125-year-old campus. The 44,100-square-foot building houses an unusual hybrid program of eight science classrooms, a 700-seat auditorium, a student dining hall, and administrative offices in spaces that foster a robust learning community, inspire scientific inquiry, and promote environmental stewardship in everyday experience.

Sacred Heart Preparatory is a 550-student, independent, coeducational, Catholic high school located on the 64-acre campus of the K-12 Sacred Heart Schools in Atherton. The distinctive red brick and sandstone Main Building, built at the time of the school’s founding in 1898, still dominates the center of campus. The Homer Center is located near it on a former recreation field.

Michael J. Homer was an early Silicon Valley pioneer who played an important role in the development of the personal computer, the internet, and the handheld digital device. In honor of him and as a reflection of the innovative Silicon Valley culture he helped to create, the Homer Center brings together science, nature, and community in one unique educational environment. We positioned the building to help link an adjacent gymnasium and classroom buildings with the Main Building. The center’s east–west orientation optimizes pedestrian circulation around the site, allows for passive solar design, and brings in daylighting and natural ventilation. We arranged important community rooms—the student life office, the dining hall, and the auditorium—on the first floor of the building and wrapped these around a courtyard with a large native oak tree. Together, this forms an indoor-outdoor hub of campus life. The building skin is made of red slate panels that are similar in height, proportion, texture, and color to the red brick of the Main Building nearby. Lightweight steel sunshades articulate the facade and provide daylighting control and weather protection.

We placed eight large science classrooms on the second floor to make them convenient to the center of student life below and to express the importance of science to the mission of the school. The 100% daylit classrooms are designed to accommodate both lecture and lab work in one flexible space, with ample room provided for special projects. The design of the

building supports this focus on science by clearly demonstrating its environmental agenda. A wide range of strategies—including natural ventilation, daylighting, high-performance building envelope, energy-efficient systems, and renewable energy—contribute to an energy reduction of 69% and a water use reduction of 50% below a typical school building in the region. Building energy, water use, weather data, and other information is displayed in real time on an interactive building dashboard at the main entry. This data is also available to students if they wish to investigate the building’s performance as a class project. Exposed seismic frames, trusses, and other elements celebrate the physics of the center’s structure. Four classrooms overlook a roof with a photovoltaic array and plantings designed to attract native birds and butterflies. A student-cultivated garden provides fresh produce to the dining hall, and a large rain garden—overseen by a life-size sculpture of a gator, the school mascot—manages on-site stormwater.

The Homer Center was first in the nation to receive a LEED for Schools Platinum certification. It illustrates a hybrid educational environment that weaves together academics, social-emotional learning, and deep environmental elements of twenty-first-century education.

Buildings done right can be an amazing teaching colleague.brian bell , assistant principal sacred heart preparatory

a historic US Army warehouse at Fort Mason has been transformed into a campus for the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI), creating a dynamic new hub for expanded arts education and public engagement. This adaptive reuse project preserves the industrial integrity of the landmark structure, supports the school’s pedagogical goals, and integrates advanced sustainable building systems.

San Francisco Art Institute is “dedicated to the intrinsic value of art and its vital role in shaping and enriching society and the individual.”32 In support of this mission, SFAI created an arts campus at the heart of the vibrant Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture (FMCAC) in an urban National Park. The design interweaves historic and contemporary, leveraging the dramatic light-filled landmark industrial structure to create studios, a workshop, a media theater, flexible teaching spaces, and public exhibition galleries.

By integrating energy-efficient systems and structural upgrades, the life of this building has been extended for another hundred years. The adaptive reuse of this landmark building results in a 74.9% reduction in greenhouse gas impact from that of a standard new building.33 The rehabilitation of the historic concrete and steel structure capitalizes on not only the embodied carbon of the existing building materials but also the embodied cultural history.

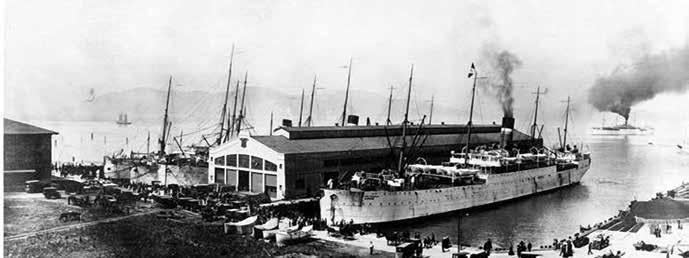

Constructed in 1909 as part of the San Francisco Port of Embarkation, the more than 400-foot-long Pier 2 Shed served as a warehouse and processing point for military personnel and supplies from 1911 until the US Army left Fort

Mason in 1962. During World War II, more than 1.6 million troops and 23 million tons of cargo embarked from Fort Mason to the Pacific theater. In the 1970s the vacant site was transformed into FMCAC. SFAI, FMCAC, and the National Park Service (NPS) formed a unique public-private partnership to create the new arts center in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and Pier 2 Shed evolved from a military processing point into an interdisciplinary art campus and community cultural center.

The adaptation of Pier 2 promotes not only SFAI’s social and cultural value but also its economic and environmental values. A collaborative planning process engaging SFAI students, faculty, and administration; FMCAC; the NPS; and the California Office of Historic Preservation addressed diverse perspectives. The design integrates cost-effective sustainable systems, including a high-efficiency radiant slab floor, maximum use of daylighting, and a photovoltaic solar system. The first phase of the project included the complete rehabilitation of Pier 2 Shed, with structural and building systems upgrades, building envelope restoration, and integration of sustainable systems. The second phase focused on the interior transformation of the warehouse into the new SFAI art facilities and public galleries. We actively supported a complex funding program, which included the NPS Save America’s Treasures program, the Federal Historic

Tax Incentives program, and a grant from the US Department of Energy.

The design sensitively integrates 160 individual studios, public exhibition galleries, flexible teaching spaces, a black box theater, and a workshop/ maker space. The dynamic contemporary learning environment respects the integrity of the dramatic industrial landmark. New second-level studios are added at the sides of the open shed volume and are held away from the existing structure; in this way new is clearly articulated from historic. The mezzanines flank a large atrium space, which is visible from the public entry. We gathered individual artists’ studios around common rooms and seating areas; these variously scaled spaces invite exhibition and creative engagement. We positioned a glassfronted workshop, formal galleries, and performance spaces at the southern entrance of the building for convenient public access and to promote engagement with the arts. The SFAI Pier 2 project honors the history of Fort Mason while transforming this historic landmark into a vibrant, sustainable community art hub for future generations.

The San Francisco Art Institute at Fort Mason Center is a container of something greater than itself. During World War II, Pier 2 Shed was a container for instruments of war on their way to the Pacific theater. Today, it is a container for art, creativity, and community for students, faculty, and the city.

ryan jang architect , lms

ryan jang architect , lms

A