Keith Krumwiede

Keith Krumwiede

If you’re reading this foreword you’ve likely already skimmed through the book. You’ve flipped through the houses—loving some, questioning others—and started to form opinions about this menagerie of domestic dreams. If you’re like me, you don’t read the foreword to a book until after you’ve checked out the main attraction. You may even skip it entirely, I often do. So these thoughts are less about describing what you’ll see and more about offering some reflections upon what you’ve presumably already seen: 365 houses, drawn over the course of 365 days. Which, let’s face it, is a bit crazy. One could be tempted to see this as the work of a madman (think Jack Nicholson in The Shining relentlessly typing out “all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”). Except here our madman wakes each day and thinks: “oh shit, one more house is due today, what have I gotten myself into?” And it is a bit mad, but it’s also more than a bit beautiful, and instructive. One House Per Day tells us a lot about who we are as architects, but it also tells us about who we are as humans, seeking and making nests to support our lives and the lives of those with whom we live.

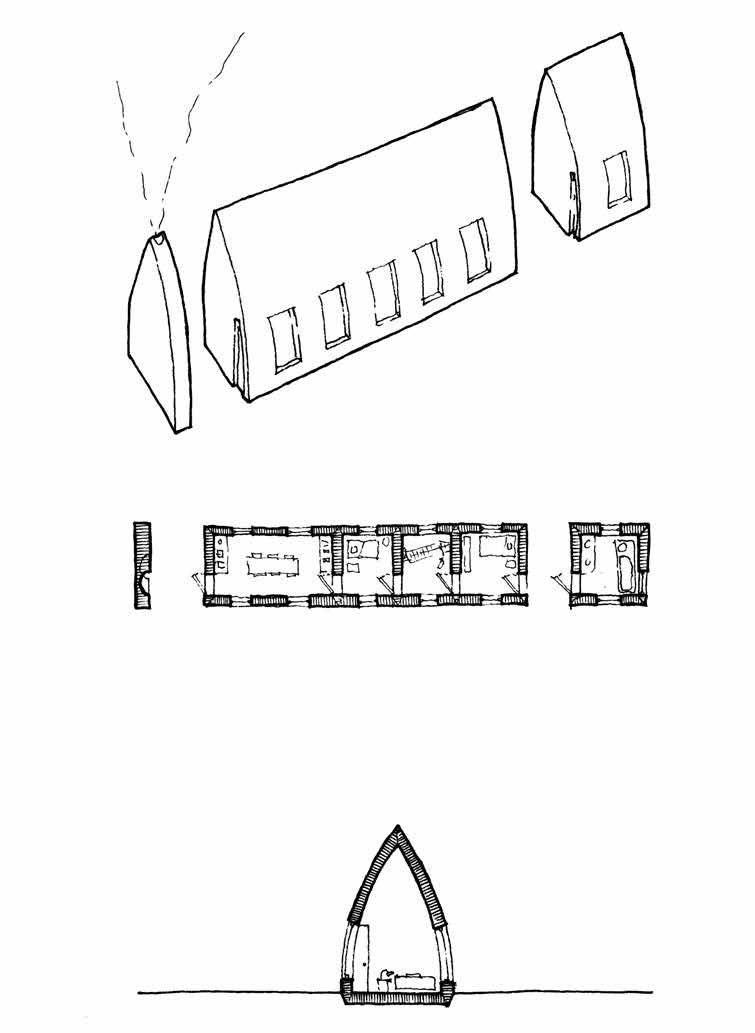

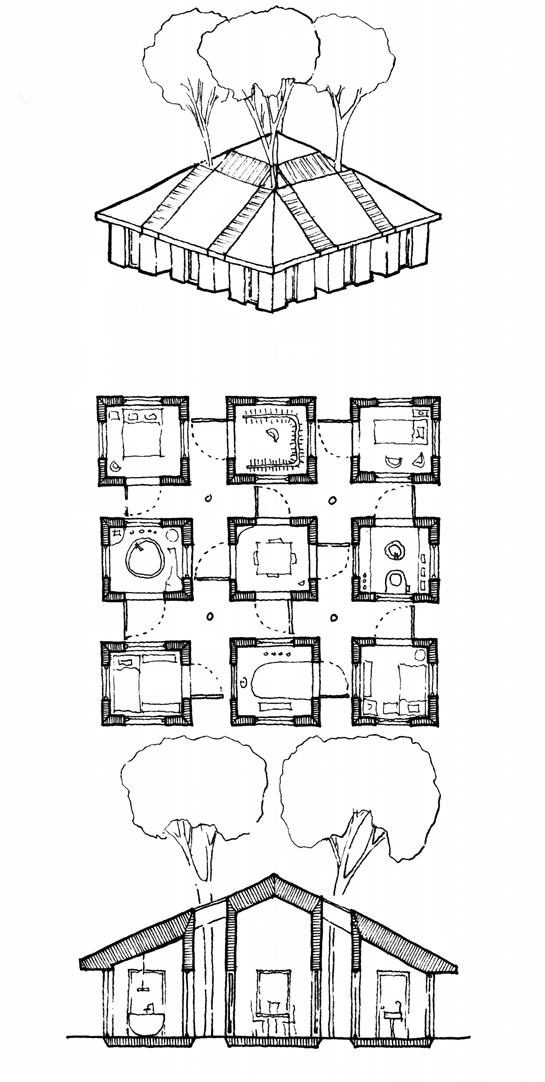

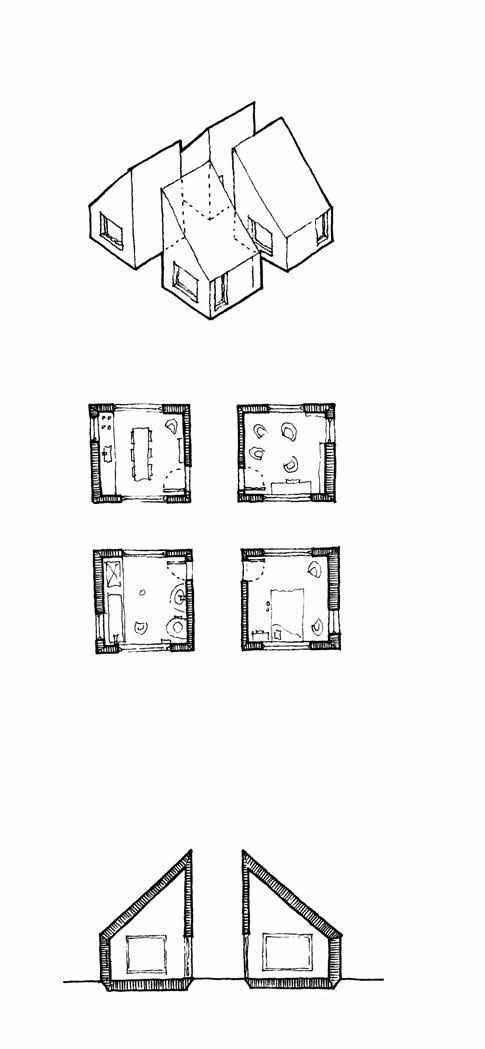

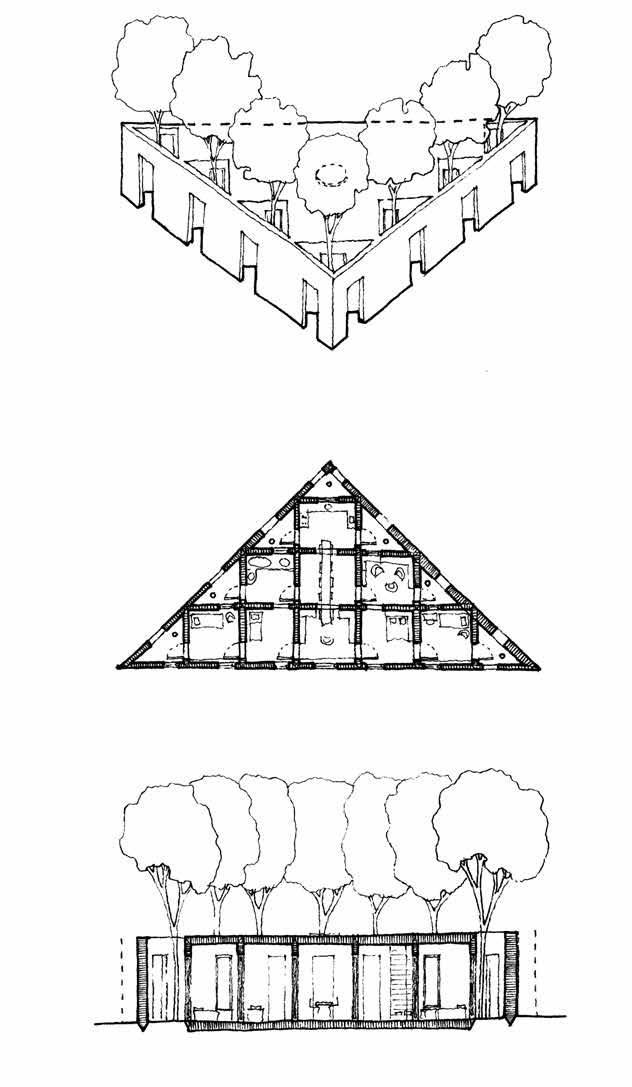

The detached house, isolated in its own little Eden, has long been the privileged domain of the single family. It has also long been seen by architects as the ideal building type through which to exercise their formal ambitions. Its seemingly stable program (a collection of rooms designated for living, cooking, dining, sleeping, washing, etc.) allows the architect to imagine (or imagine they’re imagining) new and exciting arrangements of architectural matter—walls, roofs, doors, windows. And while there may be some pretense toward programmatic invention, more often than not an architect working on a house is an architect working on their architecture. The imagined inhabitants, if any are imagined, are simply witnesses to the formal drama of the architect dreaming up architecture.

A house, however, is not simply a formal exercise. Every house organizes and frames the lives of its inhabitants, charting a loose choreography for their domestic life. Andy Bruno knows this, and in these houses— lovingly executed day in and day out—he explores other arrangements for how we live and how we might live, both alone and, more importantly,