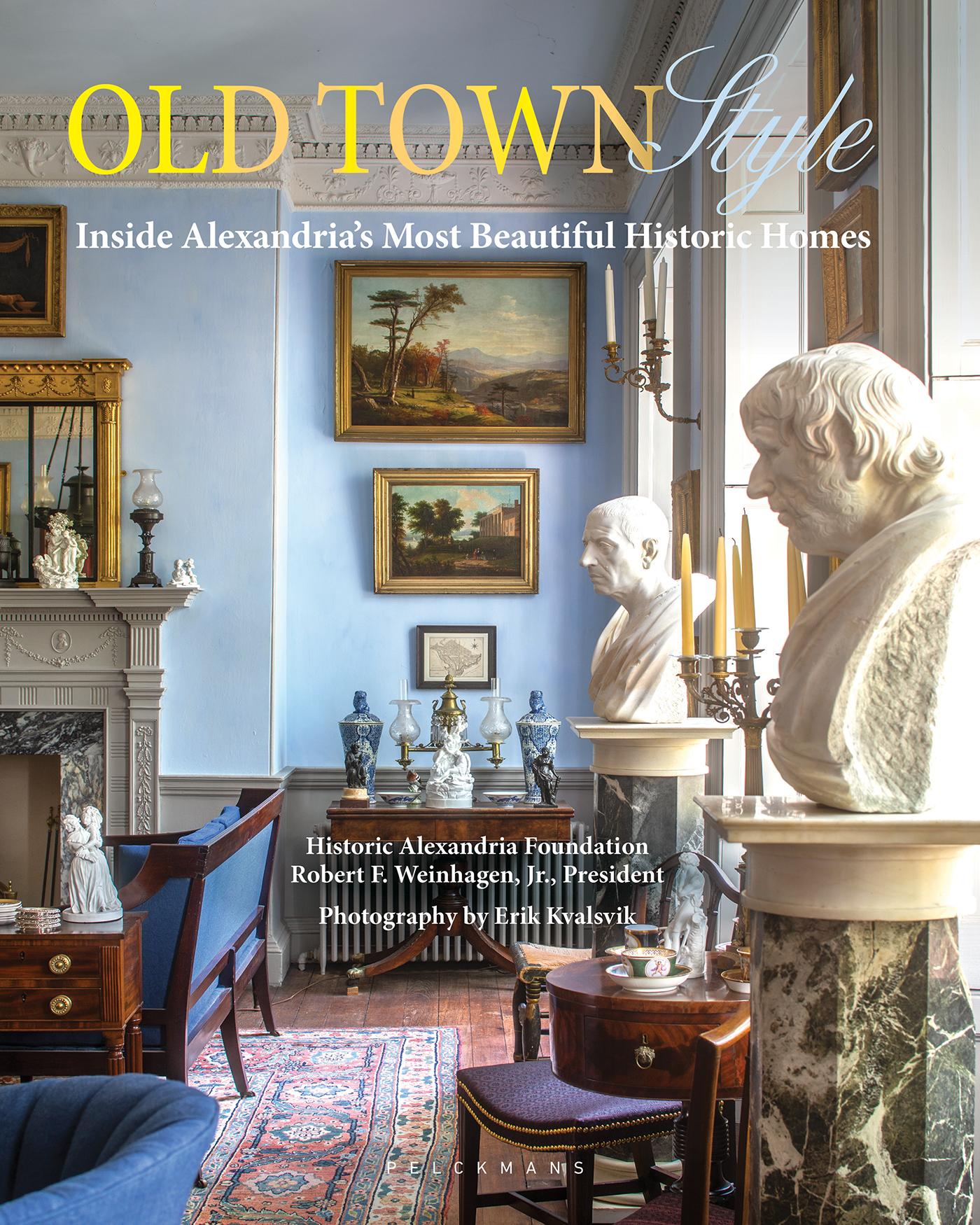

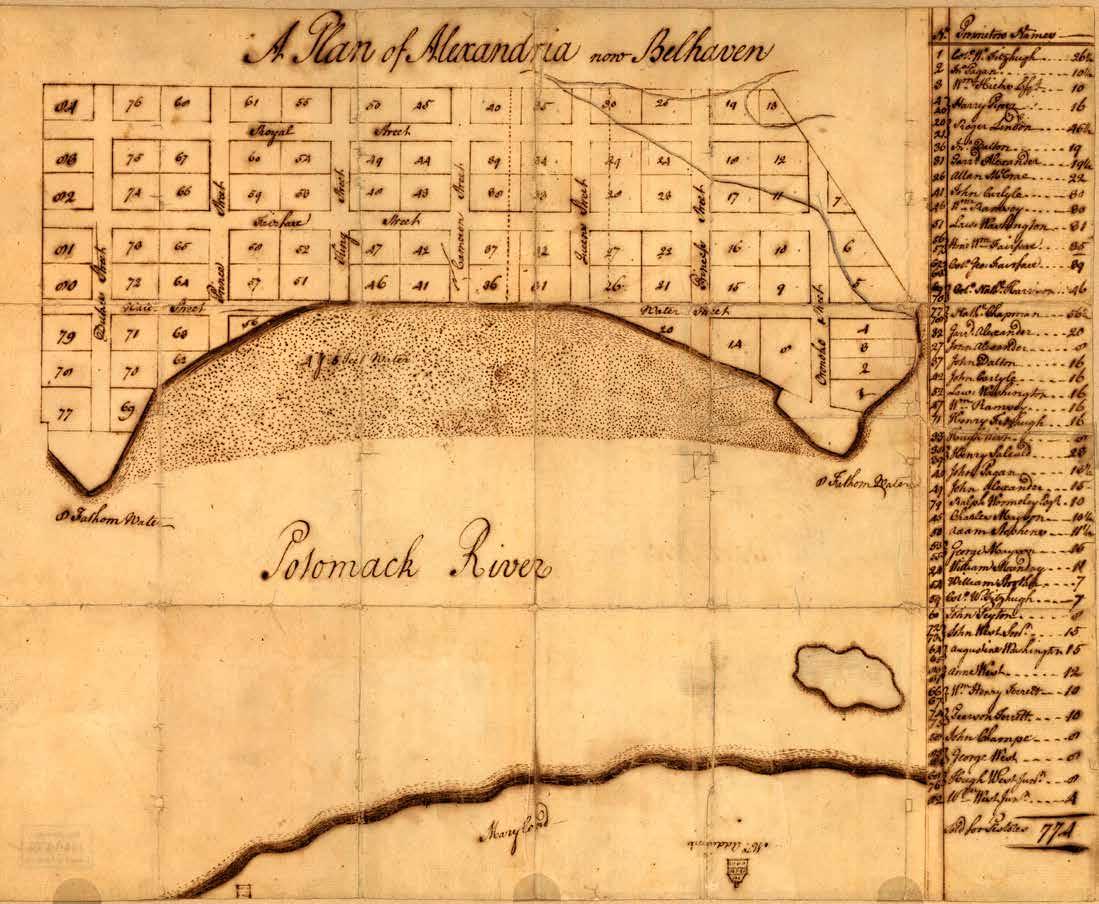

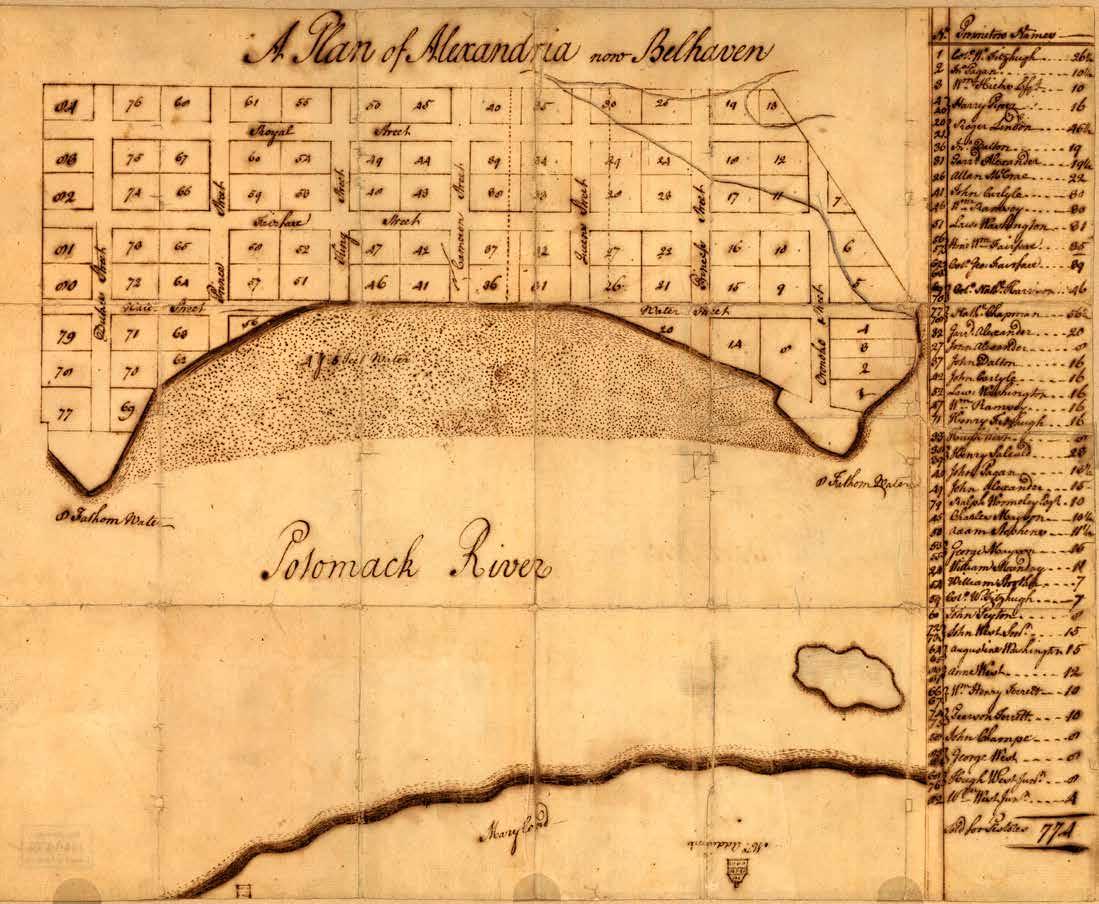

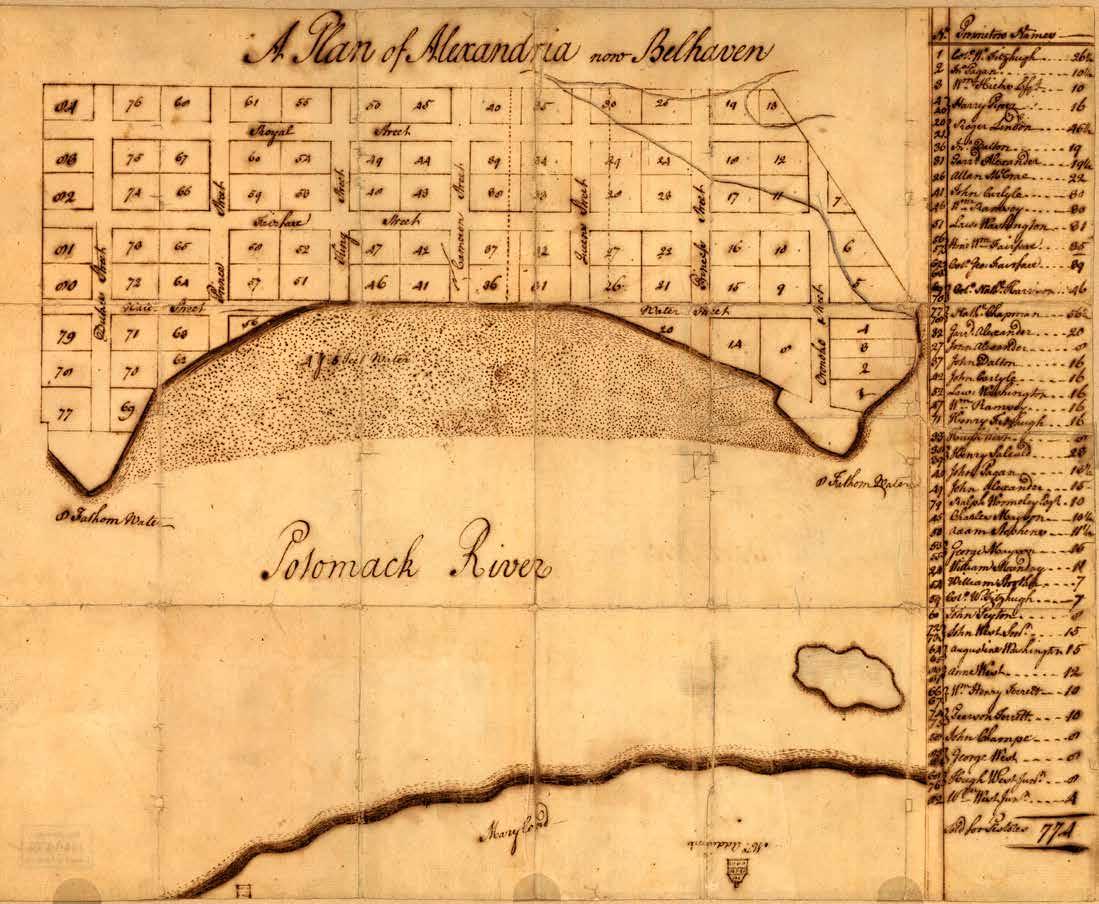

Set along the banks of the Potomac River, just a few miles south of the nation’s capital and upriver from George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Old Town Alexandria is one of America’s earliest and most distinguished seaport communities. Founded in 1749, it quickly became a thriving center of trade and culture – a crossroads where the ideals, ambitions, and artistry of a young nation took form. With its ordered grid of brick streets, elegant townhouses, and proximity to the centers of early American power, Alexandria has always stood at the intersection of commerce and civility, craftsmanship and civic pride.

In May of that year, the Virginia Assembly officially established the town, and a young George Washington assisted in surveying its eighty-four half-acre lots along the river’s edge. Early regulations required each buyer to build a substantial house – at least twenty feet square and nine feet high – to ensure a settlement of permanence and dignity. The resulting streetscape of red-brick houses, their chimneys and cornices crafted by local masons, reflected the refined Georgian and Federal character of Philadelphia more than the decorative colonial style of Williamsburg. Scottish merchants, Quaker settlers, and skilled artisans soon filled the new town with industry and aspiration.

By the late eighteenth century, Alexandria’s busy wharves linked the region to the wider world. Cargoes of wheat, tobacco, and corn departed for Europe and the Caribbean, while ships returned laden with rum, molasses, and goods for inland trade. The town’s prosperity drew merchants, craftsmen, and laborers – both free and enslaved – whose work shaped the architecture that endures today. In 1785, a population of about three thousand supported a flourishing community of blacksmiths, coopers, silversmiths, butchers, and builders, along with two churches and a Quaker meetinghouse. The scene was one of enterprise and energy – a maritime town alive with the sounds of hammers, hooves, and sails on the river.

ARevolutionary era residence revived with bold art, layered style, and a thoughtful nod to the past.

Built in 1778, this distinguished residence once served as both home and surgery office for Dr. William Brown, a Revolutionary War-era physician and the first president of the Alexandria Academy – a school for orphaned and poor children. A Scotsman by birth, Brown brought his medical practice to Alexandria in 1786. Remarkably, his upstairs office still stands – preserved with its original oven and glass-front bookcases, etched with the names of visitors from centuries past. The basement cellar reveals rare 18th century details, including a coal chute and an ice well operated by a pulley system. The grounds also once included a smokehouse, stable, and carriage house – powerful symbols of wealth and status in the 18th century.

It was the walkable charm of Old Town, the ginkgo-lined streets, and the home’s deep sense of time and place that first drew the owners in. Their sensitive approach to renovation – honoring the original structure and preserving its historic bones while introducing a complementary addition – feels both contemporary and entirely fitting. The new space, graceful and welcoming, offers a relaxed backdrop for art, gatherings, and everyday living. Meanwhile, the house retains its warmth, character, and the quiet soulfulness that only centuries can bestow. Together, they form a rich dialogue between past and present –layered, lived-in, and beautifully at ease.

Across these pages, the house’s eclectic spirit comes into focus: a library wall curated with sculpture and busts, a staircase enlivened with hand-painted botanicals, and a Swedish Mora clock presiding in the hall. With embroidered linens and verdant garden views, the bedroom conveys understated luxury, while the terrace outside extends the sense of ease into the landscape. Together, these spaces illustrate the home’s balance of historic character and contemporary artistry.

Strolling down the stretch of Prince Street known as “Gentry Row” is like stepping into a painting of Alexandria’s seaport past. This elegant, tree-lined avenue where wealthy merchants and prominent Alexandrians once lived is graced with impeccably preserved 18th-century homes, each a testament to the rich architectural and cultural history of Old Town. Among them, one house stands apart – a grand four-story Georgian townhouse with a classic brick facade and an inviting period garden. This is the Fairfax-Moore House, an enduring landmark not only of Alexandria’s history but of the American preservation movement itself.

The Georgian style, which flourished in the American colonies from the early 1700s to the Revolutionary era (and even on into the early 19th century), is known for its symmetrical proportions, classic brickwork, and refined decorative details. Inspired by the grandeur of English Palladian architecture, these homes were built to exude harmony and permanence. With its stately presence, the Fairfax-Moore House, built in 1790, exemplifies this tradition, blending grace and grandeur in equal measure.

This historic home, set in close proximity to the Old Town waterfront, traces its origins to 1801, when Ephraim Mills a trunk maker and wheelwright – purchased the lot for $80 in silver, agreeing to build a house within two years. By 1803, Mills had completed a simple flounder-style dwelling, later expanded with a two-story front addition. According to some accounts, Mills may have crafted trunks for George Washington himself.

Throughout the 19th century, the house weathered turbulent times: the War of 1812, the economic depression of the 1820s, and the Civil War. Sold three times at public auction to settle debts, it gradually slipped into neglect. For a time, it stood beside Shuck’s Oyster House – part restaurant, part brothel. The current owners still find the occasional oyster shell in the garden, a quirky relic of the past.

The two-story entrance hall strikes a tone of updated classical elegance, where antique details are reimagined in a fresh, modern context.

Built in 1802 by Irish biscuit baker Henry Nicholson, this four-story brick residence stands on Alexandria’s first lot, sold at auction in 1749 to merchant John Dalton, who partnered with John Carlyle to import and export goods along the Potomac River. Over time, the neighborhood transformed from a bustling hub of saloons and warehouses into a tranquil enclave just steps from City Hall and the historic Carlyle House and garden.

Over the centuries, the house has served as a bakery, antiques shop, and mayor’s residence. A two-story ell original to the property was removed in 1915 by the Corby Baking Company to make way for a large shed and alley. They shifted the property line twelve feet west, creating an alleyway – now a coveted driveway – connecting to the Crilley Warehouse behind the property. The imposing brick wall on the west side of the lot, enclosing the entire garden, is thought to incorporate bricks salvaged from the demolished ell.

In the early 1930s, restoration expert and antiques dealer Martha Monfalcone embarked on a meticulous fiveyear project to return the house to its early 19th-century splendor. By 1969, a city preservation map ranked the house among Alexandria’s most architecturally significant homes – one that “should be retained.”

1803

Agrand example of Alexandria’s Federal architecture, the Lord Fairfax House was built in 1803 by William Yeaton, a noted New England architect and shipwright best known for designing George Washington’s tomb. In 1816, the home was purchased by Thomas, 9th Lord Fairfax, as a winter residence. His son, Dr. Orlando Fairfax – a prominent local physician – lived here until 1876, apart from the Civil War years when the Union Army commandeered the house.

The property remained a private residence through successive owners, including the Windsor and Creole families, and never saw subdivision apart from its wartime use. Dr. Morgan Delaney, the long-time President of the Historic Alexandria Foundation, considered it the finest Federal house in Alexandria.

circa 1806

Elegantly recessed from the bustle of Prince Street, the Patton-Fowle House is a distinguished 5,000-square-foot mansion and a striking example of Federal architecture. Its symmetrical facade is anchored by a grand central entry framed by fluted pilasters and crowned with a Palladian tripartite window. Sidelights flanking the door and a prominent second-story window offer a glimpse into the elegant spiral staircase within –a hallmark of the home’s refined interior.

The home began as a modest flounder house built in 1806 by James Patton, who sold it just five years later to merchant William Fowle. In 1820, Fowle commissioned famed architect Charles Bulfinch to transform the structure into a high-style mansion. Today, the property is protected by a preservation easement through the Historic Alexandria Foundation and the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Fowle, a partner in a shipping firm, entertained President John Quincy Adams at the house in 1841. By mid-century, he owned multiple warehouses and traded in soap, candles, nails, New England rum, and Madeira wine. Five generations of his descendants lived here over 158 years, except during the Civil War, when – due to Confederate sympathies – the family was forced to vacate. A presidential pardon and Supreme Court ruling allowed them to reclaim the home by 1870.

The living room features a Robert Rea painting over King of Prussia fire surround.

Behind its traditional façade, this grand residence reveals a striking contemporary interior, centered on a Palladian window and graceful spiral staircase. In the parlor beyond, sleek furnishings meet a King of Prussia marble fireplace in a dialogue of old and new.

Inside, the décor strikes a confident balance between past and present. Classic architectural details frame a series of stylish, contemporary spaces: the kitchen’s clean-lined cabinetry and honed marble counters offer a refined twist on traditional style; the dining room pairs sleek chairs with a striking modern light fixture and a gallery wall of collected artwork; and in the family room, a deep purple velvet sofa adds a note of drama and personality, layered with eclectic textiles, personal mementos, and original art. Together, these interiors feel both grounded in history and refreshingly individual.

The renovation proved so all-consuming that the owners couldn’t bring themselves to watch The Money Pit, the 1980s comedy about a home makeover gone wildly awry (and way over budget). Yet their commitment to preserving the home’s character never wavered. Original crown moldings, lofty ceilings, and period details were carefully retained, while a curated mix of traditional, local, and contemporary art –infused with personal touches – breathed new life into the old walls. The result is a warm, stylish family home that embodies both the charm of Old Town and the ease of modern living.

This stately three-story brick townhouse with a full basement – along with its identical next-door twin – was built in 1852 by William McVeigh on the site of a modest frame house he purchased at auction two years earlier. By April of that year, the Alexandria Gazette and Virginia Advertiser reported that “the large and commodious dwellings on Prince Street… have been finished and are now occupied.” Like many Old Town houses, this one saw a series of transformations over time, including a period when it was divided into four apartments. Fortunately, a prior owner returned it to a single-family residence and restored much of its original character in the late twentieth century.

When the current owners acquired the home, the restoration was largely complete. Their primary change was to remodel the kitchen – removing a dated Tuscan scheme and replacing it with a timeless design in harmony with the home’s architecture. Their guiding principle was that any update should be seamless, timeless, and respectful of the original structure. A proper restoration, they believe, should never announce the year it was done. Wood floors, mantels, windows, doors – anything original – should remain unaltered whenever possible. The goal was to marry 21st-century comfort with the enduring strength and elegance of the 19th-century design.

In the living room, 19th-century architecture meets 21st-century comfort, with rich finishes and relaxed modern seating.

Author: Robert F. Weinhagen, Jr.

Book Committee:

Robert F. Weinhagen, Jr.

Laura Dowling

William Patrick Burchette

Christina Brathune Butora

Mary Sparks Sterling

Photography: Erik Kvalsvik

Lay-out: Jan de Coster

© 2025 Historic Alexandria Foundation and Pelckmans Uitgevers nv Brasschaatsteenweg 308, 2920 Kalmthout, Belgium

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored or made public by any means whatsoever, whether electronic or mechanical, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

D/2025/6407/14

ISBN 978-90-5856-754-3

NUR 648

pelckmans.be facebook.com/pelckmans.be instagram.com/pelckmans.be