T R A N S L AT E D B Y

J O N AT H A N G R I F F I N

W I T H A P O S T S C R I P T B Y J E A N L O I Z E

remained unknown for many years. At last, in 1954, the m

Garrec in Paris. The Postscript by Monsieur Loiz e explains its relation to the book, also called Noa Noa, which was published in 1901 under the two names of Paul Gauguin and Charles Morice.

The “genuine version of Noa Noa by Gauguin unaided” is an im por tant document – a painter putting down in words an experience that drew from him great paintings. It is also a beautiful piece of writing: amusing, acid, wide-eyed, moving. Gauguin feared that, unedited, it would seem absurdly cr ude; and no doubt it would have, to most readers in his day. But we want it as it is – its sketch for m, jerky directness, authentic freshness.

In translating it, one tries t o keep out of the way: to change it into smooth English prose would be to slip back into the error of Charles Morice. Only, since the facsimile edition is there for reference, I have allowed myself some liberty with the punctuation, hoping to preser ve the effect of the original yet make it, here and there, easier to follow.

J. G.

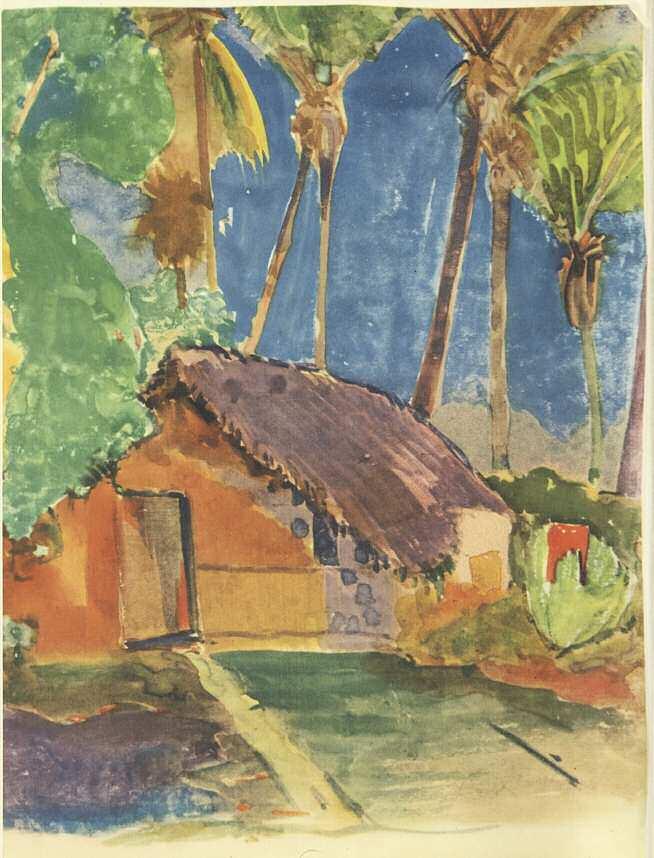

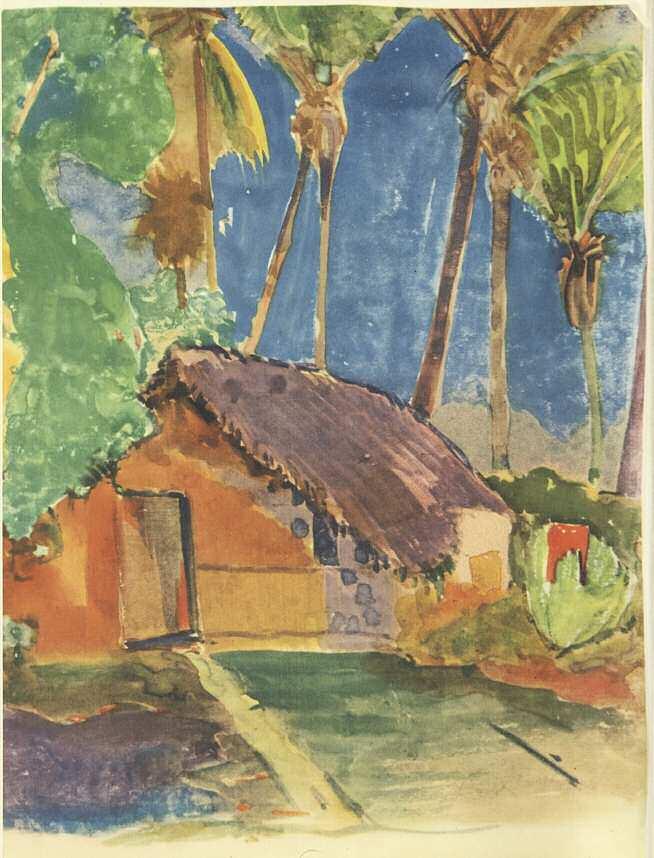

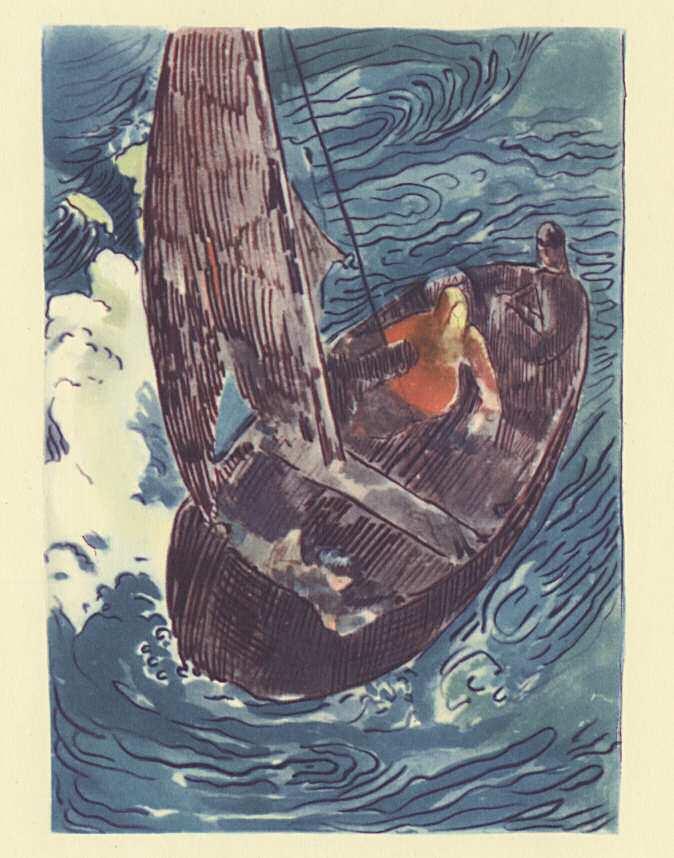

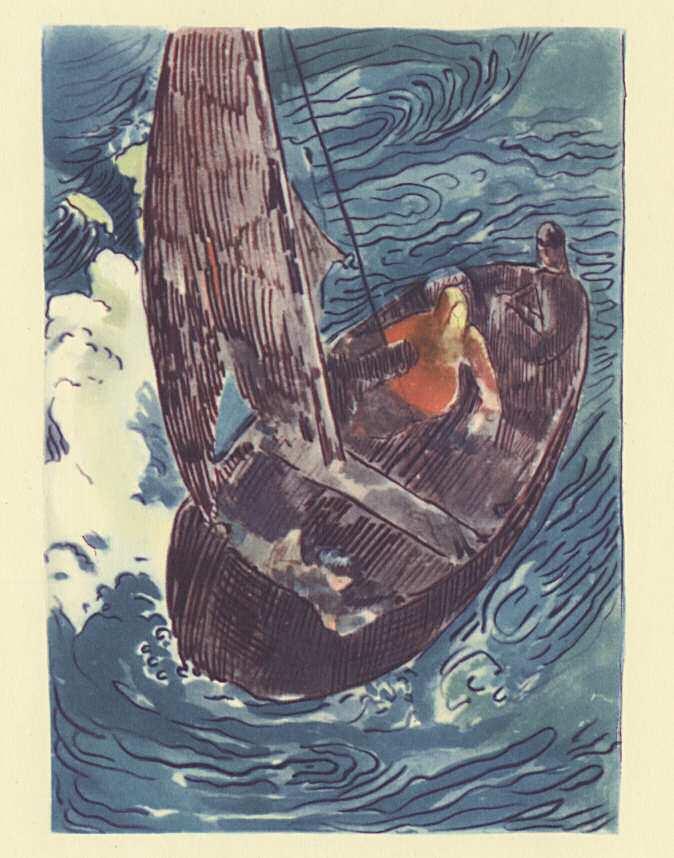

FIor 63 days I have been on my way, and I bur n to reach the longed-for land. On June 8th we saw strange fires moving about in zig-zags ––fisher men. Ag ainst a dark sky a jag ged black cone stood out. We were rounding Moorea and coming in sight of Tahiti. A few hour s later the dawn twilight became visible, and slowly we approached the reefs of Tahiti , then entered the fairway and anchored without mishap in the roads. To a man who has travelled a good deal this small island is not, like the bay of Rio Janeiro, a magic sight. A few peaks of sub[merged] mountain [were left] after the Deluge;a family climbed up there, took root, the corals also climbed, they ringed round the new island.

At ten in the mor ning I called on Gover nor Lacascade, who received me as a man of consequence entrusted by the Gover nment with a mission –– ostensibly artistic but mainly consisting in political spying. I did all I could to undeceive the political people, i t was no good. T hey thought I was paid, I assured them I was not.

At that time the king was fatally ill, and ever y day

an end was expected. T he town had a strange look: on the one hand the Europeans –– trader s, of ficials, of ficer s and soldier s –– continued to laugh [and] sing in the streets, while the natives assumed g rave expressions [and] gossiped in low voices around the palace.

And in the roadstead an unusual stir of boats with orange sails, upon the blue sea frequently crossed by the silvered ripples from the line of the reefs. T he inhabitants of the neighbouring islands were coming in, each day, to be present at their king’s last moment, at the final taking-over of their islands by the French. For their voices from on high brought them war ning –– (ever y time a king is dying, their mountains, they say, have sombre patches on some of their slopes at sunset).

T he king died and lay in state in his palace, in the full-dress unifor m of an admiral.

T here I saw the queen – Marau was her name –d e c o r a

draperies. When the director of public works asked my a d v

Artistically, I signed to him to look at the queen as, with the fine instinct of the Maoris, she g racefully ador ned and tur ned ever ything she touched into a work of art. 8

“Leave i t to them, ” I re plied.

Having only just ar rived, rather disappointed as I was by things being so far from what I had longed for and (this was the point) imagined, disgusted as I was by all this European triviality, I was in some sort blind. And so I saw in the already ageing queen a stout ordinar y woman with some remnants of beauty. T hat day the Jewish element in her blood had absorbed all else. I was strangely wrong. When I saw her ag ain later, I under stood her Maori char m; the Tahitian blood beg an to get the upper hand once more, the remembrance of her ancestor the g reat chieftain Tati confer red on her, on her brother, on the whole of that family in general, a real impressiveness. In her eyes, a sort of vague presentiment of those passions which shoot up in an instant –– an island rising from the Ocean and the plants beginning to burgeon in the fir st sunshine.

For two days the singing of h yménées –– choruses.

E ve r yo n e in b l a c k . D ir g e s. I t h o u g h t I h e a r d

Beethoven’s Sonate p ath étiq ue.

Funeral of Pomaré. –– 6 o ’clock, the cortège leaves the palace. T he troops … the authorities … black clothes white helmets. All the districts marched in order, and each with its chief bearing the French f lag. 9 n o a - n o a

Great mass of black –– So [they went] till [they reached] the part called Ar ne. A monument there, in d e s c r ib a bl e in it s c o n t r a s t w it h t h e b e a u t i f u l scener y. A for mless heap of coral lumps bound together with cement. Speech by Lacascade –– usual cliché translated afterwards by the inter preter. Speech by the Protestant Pastor, then a re ply by Tati , the queen ’ s brother.

T hat was all –– Car riages into which the of ficials piled, as though retur ning from the races–––

Along the road, confusion. T he indi f ference of the French set the example, and all this people, so g rave during the last few days, beg an laughing ag ain; vah ines once more took their tanes by the ar m, wagging their buttocks, while their broad bare feet ponderously trampled the dust of the road way. Ar rived near the Fatana river, a general scattering. In some places women, hiding among, the stones, crouched in the water with their skirts raised to the girdle, cleansing their thighs of the soiling dust from the road, [and] cooling their knees which the march and the heat had chafed. T hus restored they ag ain took the road for Papeete, their breasts leading and the conical shells which tipped their nipples drawing the muslin of their dresses to a point, with all the suppleness and g race of a healthy animal, and spreading

round about them that mixture of animal scent and of sandalwood and g ardenias. “Teine merah i Noa Noa (now ver y frag rant), ” they said.

T hat was all – ever ything went back to nor mal. T here was one king less, and with him were vanishing the last vestiges of Maoricustoms. It was all over – nothing but civilised people left.

I was sad, coming so far to…

Shall I manage to recover any trace of that past, so remote and so mysterious? and the present had nothing worthwhile to say to me. To get back to the ancient hearth, revive the fire in the midst of all these ashes. And, for that, quite alone, without any support.

Cast down though I am, I am not in the habi t of giving up without having tried ever ything, the impossible as well as the possible. My mind was soon made up. To leave Papeete as quickly as I could, to get away from the European centre. I had a sort of vague presentiment that, by living wholly in the bush with natives of Tahiti , I would manage with patience to overcome these people’ s mistrust, and that I would Know.

An of ficer of the gendar merie g raciously of fered me his car riage and his hor se. I left, one mor ning, in search of my hut.

My vah ine went with me (Titi was her name) almost an Eng lish girl but she spoke a little French. T hat day she had put on her best dress, a f lower behind her ear, –– and her sug ar-cane hat, which she had plaited, was ador ned, above its ribbon of straw f lower s, with a trimming of orange-coloured shells. Her black hair hung loose over her shoulder s; like

p a u l g a u g u i n

this she looked really pretty–––. She was proud of being in a car riage, she was proud of being welldressed, she was proud of being the vah ine of a man she believed to be important and highly paid. All this pride had nothing absurd about it, so well adapted is their cast of features for wearing dignity. Ancient memories of g reat chieftains (a race that has had such a feudal past)–––

I well knew that all her mercenar y love was composed merely of things that, in our European eyes, make a wh ore, but to one observer there was more than this. Such eyes and such a mouth could not lie.

T here is, in all of them, a love so innate that, whether mercenar y or not mercenar y, i t is still Love. Besides I w–––

In short, the jour ney passed pretty quickly –– a little insignificant conver sation, and scener y that was rich all the time but not ver y varied. Always to the right the sea, the coral reefs, and expanses of water which sometimes rose in smoke when the encounter with the rocks was too violent.

At noon we reached the 45th kilometer –– the Matiea district.

I visited the district and in the end found rather a

n o a - n o a

fine hut, which the owner consented to let to me; he would build another next door, to live in.

On our way back, next day in the evening, Titi asked me i f I would take her with me.*

“Later, in a few days, when I’ve moved in.”

I realised that this half-white girl, g lossy from contact with all those Europeans, would not fulfi l the aim I had set before me. “I shall find them by the dozen,” I said to mysel f. But the countr y is not the town.

And besides, is i t necessar y to take th em in the Maorifashion (Mau Saisis)?

And I did not know their languages.

T he few young girls of Mataiea who do not live with a tane (man) look at you with such frankness, [such] utterly fearless dignity, that I was really intimidated. Also, i t was said that many of them were sick. Of that sickness which the civilised Europeans have brought them in retur n for their generous hospitality.

After a little while I let Titi know that I would be happy i f she would retur n. And yet in Papeete she had a ter rible re putation. She buried several lover s in succession.

* Gauguin has written “her”. –– (Translator’s note).