FOREWORD

by Bret Weinstein

You hold in your hands a staggering artifact. This book contains page after page of stunning photographs of some of the most remarkable creatures and locations on Earth. The phenomena revealed here are miracles in every regard but one.

The single way in which these phenomena are not miracles is that they have been explained by science — hundreds of years of painstaking work has shed light on their fascinating causes, and these hard-earned origin stories have now become part of a collective, human birthright. It is well understood, for example, that the major landmasses of the Earth float slowly about on massive tectonic plates animated by oceans of magma beneath, their motion ripping habitats in two, dividing biological clades as they drift apart, lifting mountain ranges and mixing the biota as they slowly collide. We also now know that Milankovitch cycles — minor wobbles in our planet’s orbital dynamics — cause recurrent ice ages in which ice sheets thousands of meters thick expand towards the equator from the poles, grinding and carving solid rock as they advance, leaving rubble and new habitats upon their eventual retreat.

Most stunning of all, we know that all the biodiversity we see — every living creature on the planet — shares a common ancestor with every other, their diverse forms the result of an adaptive evolutionary process not so unlike the selective breeding imposed by farmers on plants and animals since the origin of agriculture more than 10,000 years ago.

The world is brimming with marvelous and surprising things, many of which are captured here. As you look through these images, take a moment to consider your own luck in being able to witness and appreciate them. As a human in the 21st century, you are immensely fortunate. Not only do you exist on the most fascinating and dynamic planet we have yet encountered, you are also a member of the only species with an ability to appreciate just how singular this opportunity is. And because you live in an era of advanced technology and intellectual enlightenment, you are beautifully positioned to know about the many marvels of the world, and can grapple with their meaning.

How many of your ancestors lived their entire life on a planet containing elephants, for example, without ever having any inkling that such a spectacular creature existed? For those ancestors who may have lived among elephants, would any have known of a panda? A penguin? The aurora borealis?

It is sobering to think that for most of human history, a person could only really know the marvels accessible from their place of birth. Even after written accounts and drawings began to break down these spatial and temporal barriers to knowledge, the ability to appreciate the full range of the world’s wonders — and to separate fact from fiction — was incredibly limited until the 19th century, when photographic equipment finally allowed one person to capture an image — a single instant in time — and transport the visual record over any earthly distance. But even after this became commonplace, at a practical level, many of the most interesting phenomena remained too difficult to document until recently.

Because you exist here and now, you can see virtually everything, not just as if you were there but, in many cases, far better than you could with your own eyes. Marsel van Oosten has traveled the globe and, with his unique take on the subject matter and his unsurpassed technical skill, captured a fantastic array of instants. After you have spent time with his work, you will know more about the world you inhabit.

A skilled nature photographer succeeds by disappearing. They capture something, and through the magic of composition, teach you exactly what they want you to understand — all without saying a word. They distort and edit the world so that we may comprehend things as they actually are. That’s a hard lesson to swallow, at first. A photographer documents with distortion the way a sculptor reveals living truths with stone.

My own trajectory as an amateur photographer taught me a great deal about the world. I learned photography in high school back in the ’80s with a hand-me-down manual SLR camera. I was a science-minded guy doing art. My artistic eye was OK, but the most valuable thing I gained was a deep understanding of the tool and its use, and a vantage point from which to watch camera technology evolve and intersect with human understanding.

Photography is a skill I treasure and that has served me well, in ways I could not have anticipated. It has given me a means to approach the wonders of nature and to share them with my family, friends, and students. And as an enthusiast and participant in the technical side of photography, it has taught me things about markets and about progress I would not otherwise have

VORWORT

von Bret Weinstein

Sie halten ein erstaunliches Artefakt in Ihren Händen. Dieses Buch enthält seitenweise Fotografien von den bemerkenswertesten Kreaturen und Orten dieser Welt. Die Phänomene, die hier enthüllt werden, sind Wunder in fast jeglicher Hinsicht — mit einer Ausnahme.

Die Ausnahme, also der Grund, warum wir nicht von Wundern sprechen können, ist die Tatsache, dass diese Phänomene alle wissenschaftlich erklärt sind — jahrhundertelange Forschungsarbeit erklärt die faszinierenden Ursachen, und dieses kausale Netzwerk ist nun Teil des kollektiven menschlichen Geburtsrechts. Es ist beispielsweise bekannt, dass die Landmassen der Erde sich langsam auf großen tektonischen Platten, die auf Magmameeren treiben, bewegen. So werden Lebensräume entzweigerissen, biologische Gruppen getrennt, aber auch Berge emporgestemmt und Flora und Fauna neu vermischt. Wir wissen auch, dass Milankovitch-Zyklen — winzige Schwankungen in der Erdrotation — wiederkehrende Eiszeiten verursachen, während derer sich meterdicke Eisplatten von den Polen zum Äquator ausbreiten, kollidieren und dabei Felsen zermahlen; zurück bleiben Geröll und, beim Abschmelzen des Eises, neue Lebensräume.

Vielleicht am beeindruckendsten: Wir wissen, dass die Biodiversität, die wir sehen, dass jedes Lebewesen auf dem Planeten einen gemeinsamen Vorfahren hat und dass ihre Diversität das Ergebnis adaptiver Evolution ist — dem selektiven Zuchtplan, den Farmer seit Beginn des Ackerbaus vor über 10.000 Jahren den Pflanzen und Tieren auferlegten, nicht ganz unähnlich.

Die Welt ist voller wunderbarer Überraschungen, und viele davon sind hier festgehalten. Wenn wir diese Bilder betrachten, sollten wir innehalten und uns glücklich schätzen, diesen Anblick genießen zu dürfen. Wir haben großes Glück, Menschen im 21. Jahrhundert zu sein. Nicht nur leben wir auf dem faszinierendsten und dynamischsten bekannten Planeten, wir sind auch die einzige Spezies, die in der Lage ist zu erkennen, wie einzigartig dieser Umstand tatsächlich ist. Da wir im Zeitalter der fortschrittlichen Technologie und der intellektuellen Aufklärung leben, wissen wir viel über die Wunder der Welt und sind in der Lage, sie zu verstehen.

Wie viele unserer Vorfahren lebten beispielsweise auf einem Planeten, auf dem es Elefanten gab, und wussten doch nie, dass so eine Kreatur existierte?

Und wie viele von jenen, die Elefanten kannten, wussten von Pandas, Pinguinen, Nordlichtern?

Es ist erstaunlich, wenn man bedenkt, dass die Menschheit historisch gesehen über sehr lange Zeit hinweg nur jene Wunder, die vom eigenen Geburtsort aus erreichbar waren, erfahren konnte. Selbst als Schriften und Zeichnungen diese räumlichen und zeitlichen Grenzen des Wissens durchbrachen, war die Fähigkeit, die Wunder der Welt in ihrer Ganzheit zu erfassen — und Fakt und Fiktion zu trennen — lange stark eingeschränkt. Im 19. Jahrhundert bot die Fotografie eine Möglichkeit, ein Bild, einen bestimmten Moment, einzufangen und als visuelles Zeugnis über weite Distanzen zu transportieren. Doch selbst nachdem diese Technologie weit verbreitet war, waren viele interessante Phänomene bis vor Kurzem in der Praxis zu schwer zu dokumentieren.

Da wir im Hier und Jetzt existieren, können wir auf virtuellem Wege fast alles sehen; und oft noch viel besser als mit eigenen Augen. Marsel van Oosten ist weit gereist und hat mit seinem individuellen Ansatz und seiner unvergleichlichen Technik eine großartige Auswahl an Momenten eingefangen. Je mehr Zeit man mit seiner Arbeit verbringt, desto mehr versteht man die Welt, die wir bewohnen.

Gute Naturfotografen sind erst dann erfolgreich, wenn sie verschwinden. Sie fangen etwas ein, und dank der Magie der Komposition lehren sie uns, was wir zu verstehen suchen — ohne ein einziges Wort zu sagen. Sie verzerren und bearbeiten die Welt, sodass wir die Dinge so verstehen, wie sie wirklich sind. Anfangs ist das eine schwere Lektion. Fotografen dokumentieren durch Verfälschung, so wie der Bildhauer lebendige Wahrheit in Stein einfängt.

Mein eigener Werdegang als Amateurfotograf lehrte mich einiges über die Welt. Ich lernte Fotografie in den 80ern, als ich in der High School war, mit einer gebrauchten manuellen Spiegelreflexkamera. Ich war ein Wissenschaftler, der Kunst machte. Mein künstlerisches Auge war passabel, aber die wichtigste Erkenntnis, die ich gewann, war ein tieferes Verständnis des Werkzeugs; mit diesem Grundwissen konnte ich die Evolution der Kameratechnologie und ihren Schnittpunkt mit menschlichem Verständnis beobachten.

Order in chaos

Interview by Aleena von Storms

A new book. That took you long enough. Yeah, 15 years, to be precise. If you want to do it right, a book like this is extremely time-consuming to make. Time has always been the biggest obstacle. I work very slowly, so to put something like this together takes ages. My wife Daniella and I had just started our 6-month sabbatical when my publisher asked me if I wanted to make a book. We decided that it was the perfect time to do it. In hindsight, I would never have been able to finish it in those six months, so the extra time the pandemic freed up came at the right moment.

OK, first things first. Who is Marsel, and how did we get here?

I was born in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. At first, I wanted to become a journalist, so I studied Dutch language and literature at the university. That’s where I realized that I spent way more time on my papers’ design than on the contents. I come from a creative family, so I guess it was inevitable that I switched to art school. After four years, I graduated in graphic design and art direction — photography didn’t appeal to me at all back then. Immediately I got a

job as an art director at one of the major ad agencies, and I did that for 15 years. Part of my job was to select photographers to shoot the ad campaigns my copywriter and I developed. By working closely with many different photographers, I learned to understand and appreciate photography, and I eventually picked up a camera myself. That’s how the hobby started. On our honeymoon to Tanzania, I got bitten by the safari bug and knew that this was what I wanted to do more. Curious whether I was any good, I decided to enter some of my work into some major international photography competitions. Every now and then, I’d win something, which made me realize that I could maybe someday become a fulltime professional photographer. During the last three years of my advertising career, I had my own ad agency, and with it came a bunch of stress. By that time, photography was a hobby totally out of control, and I started using it as an escape from life in the fast lane. And then, one day, I decided I had enough and wanted to start a new career. During the 15 years that followed, I traveled around the world, capturing the world’s wild places and animals.

Ordnung aus dem Chaos

von Aleena von Storms

Ein neues Buch. Es hat ja ziemlich lange gedauert. Ja, 15 Jahre, um genau zu sein. Man muss viel Zeit in diese Art von Buch stecken, wenn man es richtig machen will. Zeit war immer ein Problem für mich. Ich arbeite sehr langsam, und alles zusammenzustellen dauerte ewig. Meine Frau Daniella und ich hatten sechs Monate Sabbatical, als mein Verlag fragte, ob ich nicht ein Buch machen will. Es schien der perfekte Zeitpunkt. Im Nachhinein weiß ich, dass die sechs Monate sicher nicht genug gewesen wären. Daher kam die zusätzliche Zeit, die durch die Pandemie frei wurde, gerade zum rechten Zeitpunkt.

Das Wichtigste zuerst: Wer ist Marsel? Erzähl ein bisschen von dir. Ich bin in Rotterdam, in den Niederlanden, geboren. Anfangs wollte ich Journalist werden, also studierte ich holländische Sprache und Literatur. Dabei stellte ich fest, dass ich viel mehr Zeit auf das Design meiner Essays als auf ihren Inhalt verwendete. Ich stamme aus einer sehr kreativen Familie, daher war mein Wechsel auf die Kunsthochschule vielleicht unvermeidbar.

Nach vier Jahren machte ich meinen Abschluss in Grafikdesign und Art Direction — damals interessierte ich mich nicht für Fotografie. Ich bekam schnell eine Stelle als Art Director bei einer großen Werbeagentur und arbeitete dort 15 Jahre lang. Eine meiner Aufgaben war, Fotografen für die Werbekampagnen auszuwählen, die ich mit meinem Copywriter entwickelte. Im Zuge dieser engen Zusammenarbeit wuchs meine Achtung für die Fotografie, und schließlich griff ich selbst zur Kamera. So begann mein Hobby.

Während unserer Flitterwochen in Tansania ergriff mich das Safari-Fieber, und ich wusste, dass ich in diese Richtung gehen wollte. Ich reichte ein paar meiner Bilder bei internationalen Fotografie-Wettbewerben ein, um zu sehen, was ich so draufhabe. Manche davon gewann ich, und so erkannte ich, dass ich vielleicht wirklich das Zeug zum professionellen Fotografen hatte. In den letzten drei Jahren meiner Karriere in der Werbebranche hatte ich meine eigene Agentur, was sehr anstrengend war. Gleichzeitig wurde mir mein Hobby

Interview

| AFRIKA | AFRICA

For a wildlife photographer, it doesn’t get much better than Africa. Ernest Hemingway once wrote: “There can be no greater sight than that of a full-maned lion on the plains of Africa”. And although I can think of several pretty good alternatives, I certainly share his enthusiasm for the big cats: lion, leopard, and cheetah.

As I’m a cat person, you will find quite a few images of those in this chapter. You will also see images of tigers here, even though they don’t naturally occur in Africa. In 1900 there were about 100,000 tigers in the wild. In 2000 less than 4,000 were left. Poaching was rampant in India, and the future of the tiger was looking very grim. That sparked the start of a so-called ex-situ tiger conservation experiment in South Africa. The idea was to create a self-sustainable population of wild tigers outside the Indian continent, much like a backup plan. Despite the skepticism (which is typical for most ex-situ conservation initiatives), the project proved to be very successful. The tigers easily adapted to the African ecosystem, and were quickly hunting and mating like their brethren in India. We now know that this is a viable option — tigers can adapt to a new habitat. It may not be perfect, but keep in mind that there are currently more tigers living in captivity in Texas than in the wild.

Africa is, however, not only about wildlife. From ancient deserts to pristine swamps, and from rolling savannas to mist-shrouded mountains — Africa has it all.

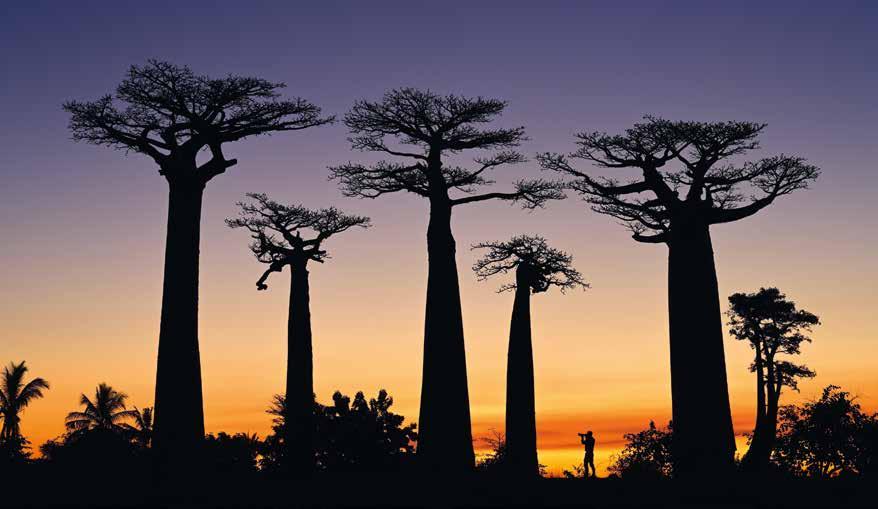

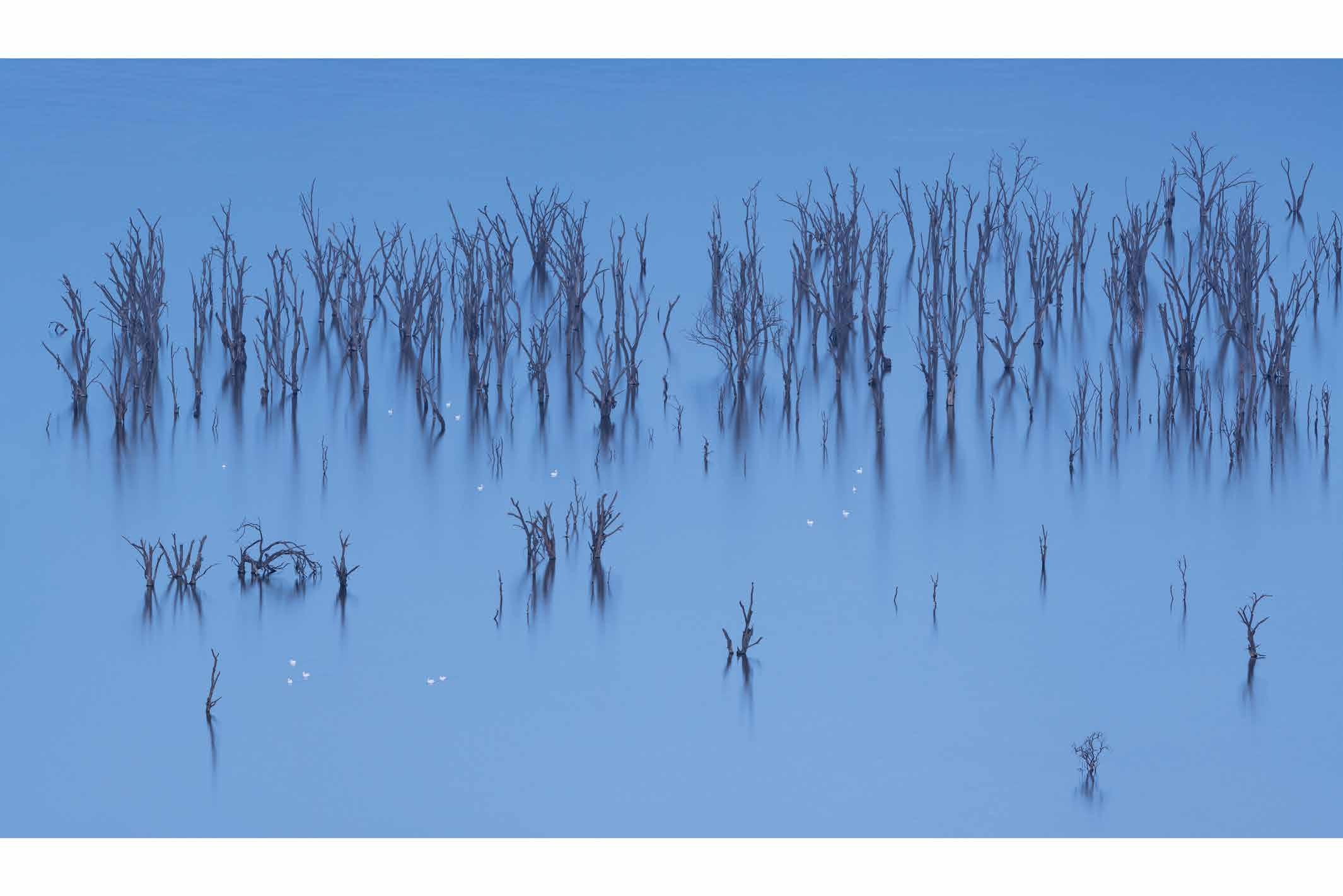

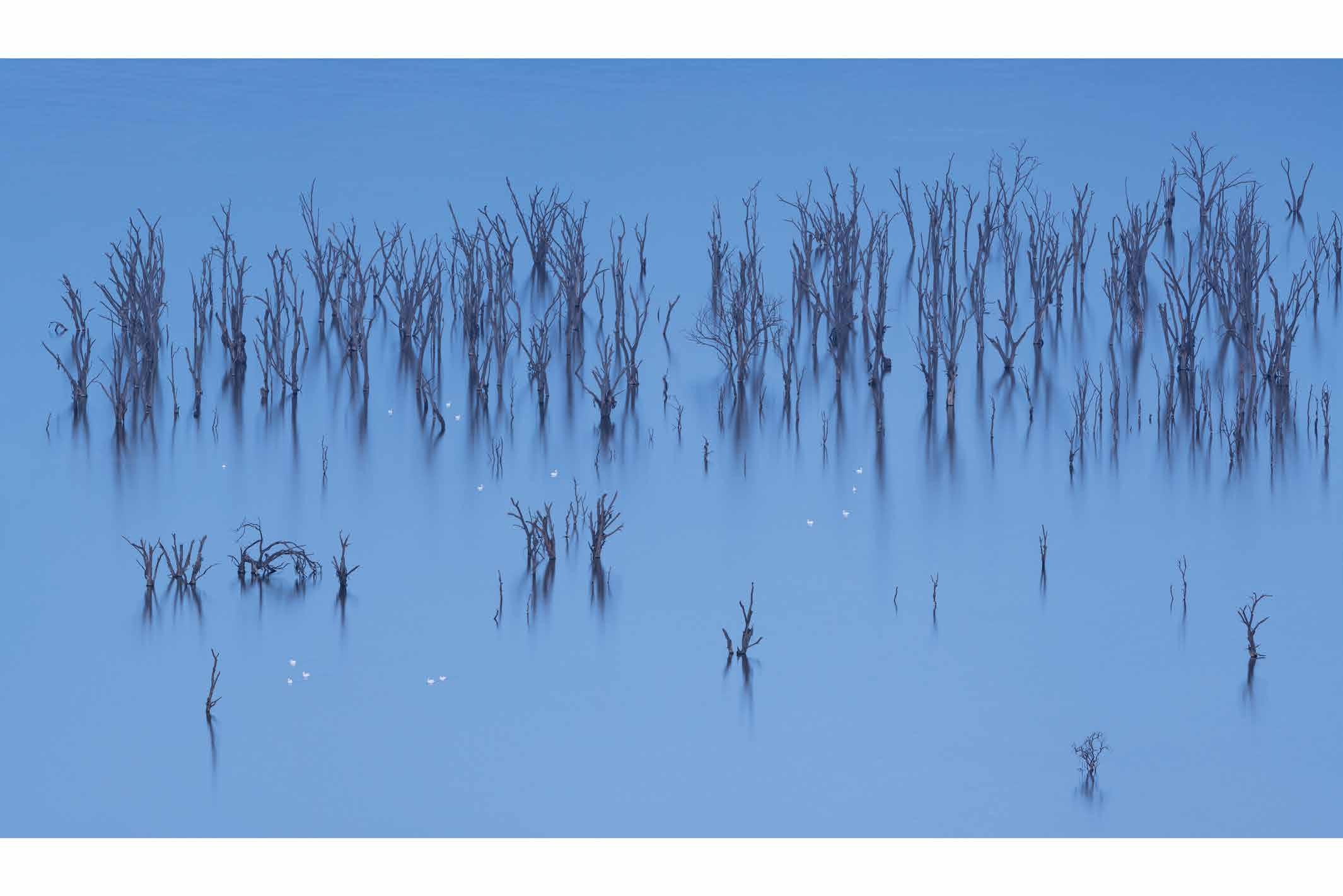

Many of my best landscape photography experiences were also in Africa — the Sahara in Libya, Chad, and Egypt; the Tsingys in Madagascar and the forests of Lower Zambezi National Park in Zambia.

The variety of landscapes and wildlife on this beautiful continent is astonishing and it’s hard not to get mesmerized by it. But when you look at these images, you should realize that many of the species and habitats you see are under threat from human interference in the form of clearing animal habitats for agriculture, as well as mass hunting and poaching for animal products such as skins, ivory, and rhino horn.

Für einen Wildlife-Fotografen gibt es nichts besseres als Afrika. Ernest Hemingway sagte: „Es kann keinen erhabeneren Anblick geben als einen vollmähnigen Löwen in der afrikanischen Steppe.“ Mir würden zwar ein paar gute Alternativen einfallen, aber ich teile seine Begeisterung für Großkatzen: Löwen, Leoparden und Geparde.

Ich bin ein Katzenliebhaber, daher kommen in diesem Kapitel viele Katzenbilder vor. Außerdem gibt es Bilder von Tigern, auch wenn diese in Afrika nicht heimisch sind. Um 1900 lebten etwa

100.000 Tiger in freier Wildbahn. Im Jahr 2000 waren nur noch 4000 davon übrig. Wilderer hatten in Indien freie Hand und die Zukunft des Tigers schien sehr düster. Das war der Anlass für ein ex-situ-Tigerschutzprojekt in Südafrika. Das Ziel war, wilde Tiger auch außerhalb Indiens langfristig heimisch zu machen, sozusagen ein Plan B. Trotz der Skepsis (die den meisten ex-situ-Initiativen entgegenschwingt) war das Projekt sehr erfolgreich. Die Tiger passten sich dem afrikanischen Ökosystem problemlos an, sie jagten und pflanzten sich fort, genau wie ihre Verwandten in Indien. Nun wissen wir, dass dies eine realistische Alternative ist — Tiger können sich erfolgreich an einen neuen Lebensraum anpassen. Es ist sicher keine perfekte Lösung, doch man muss bedenken, dass in Texas mehr Tiger in Gehegen gehalten werden als weltweit in freier Wildbahn vorkommen.

Doch Afrika hat mehr zu bieten als wilde Tiere. Von uralten Wüsten zu geheimnisvollen Sümpfen, von karger Steppe zu nebelumwobenen Bergketten — Afrika hat sie alle. Viele meiner besten Landschaftsfotografien habe ich in Afrika aufgenommen: die Sahara in Libyen, Tschad und Ägypten, der Tsingy-Nationalpark in Madagaskar und die Wälder des Lower Zamzebi Nationalparks in Sambia.

Dieser Kontinent erstaunt mit seiner Vielfältigkeit an Landschaft und an wilden Tieren, und es ist schwer, sich ihm zu entziehen. Doch wenn man die Bilder betrachtet, versteht man, dass viele dieser Tierarten und Lebensräume durch den Menschen bedroht sind; Lebensräume müssen der Landwirtschaft weichen, Tiere werden für ihre Felle, Elfenbein und Rhinozeros-Hörner in großen Zahlen gewildert.

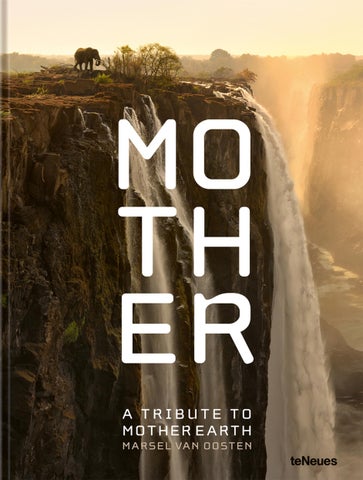

A tribute to Mother Earth

MOTHER is a visual tribute to Mother Earth by Dutch nature photographer Marsel van Oosten, a nature lover with a deep concern for the natural world. This book contains a selection of his favorite images from the past 15 years, taken on five continents: Africa, North America, Antarctica, Asia, and Europe.

Successful conservation starts with awareness, and Marsel hopes that the images in this book will reconnect people to nature, make them realize that Mother Earth desperately needs our protection, and inspire them to take action.

Marsel’s images have won many awards around the globe, and he is the world’s only photographer to have won the Grand Slam: the grand titles Wildlife Photographer of the Year, International Nature Photographer of the Year, and Travel Photographer of the Year

MOTHER is a photographic tour de force of our one and only home, Planet Earth. Marsel van Oosten’s commitment to conservation is evident in every careful composition, an artistic and powerful ode to preservation of the environment and its wild denizens.

> Art Wolfe