An Open Journey Through the Exhibition

Ousseynou Wade

Former Secretary General of the Dakar Biennale and expert in contemporary art from Africa

Jean-Yves Marin

Former Director of the Musée d’art et d’histoire de Genève and art advisor to CBH Compagnie Bancaire Helvétique

Mounting an exhibition based on a private collection is always a challenge. Questions arise about how to be faithful to the collector while highlighting the wealth of work, which rigorously reflects both a personal aesthetic and intellectual coherence.

The artwork brought together in this book spans close to a century (1929–2024). All pieces were made by artists born in sub-Saharan Africa and who have lived a part of their lives there. Far from being exclusive, this selection instead represents the first stage in the development of a more expansive vision for the collection’s future.

The African artists meet, cooperate, and influence each other well beyond administrative confines, the arbitrary boundaries of which are often absurd and stripped of cultural perspective. Eventually, this collection, which is dedicated to art and creativity in Africa, will include artists from the entire continent.

A World Out of Time

The growing success of African artists today unquestionably has its roots in ancestral heritage passed down by lineages of women and men who, for millennia, have translated their vision of the world through striking colour and enlivened forms. Far from the West’s cliché of exotic Africa, their vibrant and luminous art belongs to a dynamic of cultural reappropriation that celebrates the joy of being in harmony with nature and numerous protective deities.

Little is known about their artistic past. In the 1920s, missionaries and a handful of colonial administrators brought attention to ancient African art, encouraging artists and providing them with drawing and painting materials. This opportunity allowed them to take on new subjects while remaining true to their tradition. Some stopped after making a few pieces, but others laid the groundwork for genuine schools of art.

Artistic centers were formed during this time in Mali, West Africa, and Zimbabwe, Southern Africa. However, it was the recognition garnered by long-overlooked Congolese artists in 1929 and 1930—Djilatendo (Tshyela Ntendu) as well as the couple Albert and Antoinette Lubaki—that allowed modern African painting to make inroads into global art history. Until then, only ethnographic objects enjoyed esthetic recognition and drew the attention of European artists, one reason being that paintings had not survived, as they were often executed on degradable supports or used in decoration on the outside of homes.

One of the highlights of the exhibition is the presentation of such pieces, which are among the oldest conserved. As early as 1930, Geneva was at the forefront, exhibiting one hundred twenty Albert Lubaki drawings. Eugène Pittard, curator at the city’s Musée d’Ethnographie, organised a solo exhibition, having become an enthusiast of this little-known artist very early on. This exhibition was the second of its kind in Europe, following the one mounted at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. Museums in

Paris and London soon followed suit, which ensured the longevity of this art that seemed to spring from ancient times and that introduced new vitality. Excitement would nevertheless wane with the tumult of decolonisation in which budding artistic effervescence would struggle to find its rightful place.

African Art Unveiled

The exhibition More Than Meets The Eye on view at the Musée Rath brings to light artists who embody the developments of African art through the twentieth century until it was gradually recognised.

In the 1950s, Congolese artists Pilipili Mulongoy, the son of a fisherman, and Bela Sara, a discharged officer, drew inspiration from traditional myths—for example, the water spirit Vodoun Mami Wata, which belongs to the spiritual practices that spread from West Africa to the Caribbean.

Little is still known about Kayembe, their contemporary, who, around the 1950s, created rare realist paintings of Africa that transcend hegemonic periodisations of art history.

These artists of Central Africa, who were trained at the Atelier du Hangar in Lubumbashi, Congo, united in modernist movements that broke free from Western production. They portrayed scenes of their families and environments, abandoning perspective and the rules of traditional teaching that hindered their perception of everyday life.

At the same time, despite relative indifference, photography—introduced to Liberia as early as the mid-nineteenth century by Afro-Brazilian photographers—gradually took root and expressed the hope and joy sparked by independence movements. Seydou Keïta, who was first a locally recognised portrait photographer, opened his studio in Bamako in 1948. Ten years later, Malick Sidibé joined him and captured Bamako’s stylish weddings and dance parties across the city. Both are among the most significant photographers of the twentieth century.

Recognition

Official places of learning and artmaking were established in the 1960s. The École de Dakar, founded by Léopold Sédar Senghor, the first president of independent Senegal, promoted Africa’s artistic revival. The president envisioned globalised African art on par with European art, and the school was an important milestone for this cultural reappropriation that accompanied decolonisation. Artists like Souleymane Keïta broke new ground all while drawing inspiration from African spirituality.

Senghor’s reference to Western art was not unanimously supported. To counter his cultural influence, the Laboratoire Agit’Art movement, co-founded in 1974 in Dakar by the Senegalese El Hadji Sy, developed new forms of expression based on the crossover between traditional

Dominique Zinkpè 1969, Cotonou (Benin)

Dominique Zinkpè is a multidisciplinary artist from Benin who combines sculpture, painting, installation, and video in a practice deeply rooted in Vodoun spirituality and ancestral memory. Often created from recycled materials, his works question the cycle of life and cultural heritage. He has received several awards, and has been exhibiting internationally since the 1990s.

Generous 2021 Wood and acrylic 205 x 89 x 51 cm © All rights reserved

Atomising Exoticism: A Journey Through the Archipelago of Art in Africa

Salimata Diop

Exhibition curator, art critic, composer, artistic Director of the 15th Dakar Biennale

Entering into this collection immediately entails an agreement to relinquish reductive expectations—that a continent can be boiled down to a unique yet unchanging essence. What emerges here is not monolithic “Africa” but many Africas, a vibrant archipelago of visions in constant dialogue with themselves and with the rest of the world. The work in this body—truly a constellation of art—is an invitation to navigate well beyond flimsy missives and enduring clichés that have long defined and limited the perceptions of these creations. So, let us forget “African Art” as a set category; instead, let us welcome a multiplicity of artists, each having a singular voice, their own story, and a unique relationship to the world. Let us dive into a collection that rejects colonial geography and linear chronology, preferring to weave subtle correlations between works while unveiling unexpected connections and profound affinities through the exhibition’s proposed trajectory.

From the start, the tone is set by pioneers like Djilatendo and Lubaki. They are not presented here as guardians of an intact ancestral tradition but as vibrant starting points for a continuous exploration of modernity. Their work raises questions and escapes clear categorisation, subtly resisting the labels and colonial nomenclature that sought to bind them as works of a fantastical and controllable authenticity.

The reflection continues with an exploration of more internal dimensions. In his alphabets and cosmogonies, Frédéric Bruly Bouabré does not lock us into “tribal” particularities but speaks to us about the human condition, the need for writing, and universal harmony. At his side, Gonçalo Mabunda’s sculptural thrones, assembled using decommissioned weapons from Mozambique’s civil war, are a poignant meditation on violence, power, and transformation, a metamorphosis through visual art from instrument of death to seat of reflection.

The heart of the collection’s vitality seems to reside in its exploration of creative tensions between heritage and modernity and local and global contexts, where the plurality of contemporary African experiences are expressed with particular strength. JP Mika’s flamboyant and defiant sapeurs are flank alongside Moké’s lively street scenes, Pascal Konan’s urban perspectives, and Malick Sidibé’s photographs capturing urban youth in the 60s and 70s. Here, Africa is presented in its effervescent complexity. The exploration of intimacy and the physicality avoids hyper-sexualisation and the systematic objectification that is projected onto black bodies. Moke’s somewhat discreet eye, the fragmented, constrained bodies in Turiya Magadlela’s textiles, and also the tension expressed by Jean-David Nkot offer a sensitive and intelligent approach to sensuality and vulnerability. The work dismantles stereotypes by restoring complexity and subjectivity to the body.

Daily life is also considered while carefully skirting the picturesque. There are no folkloric markets. Instead, ordinary moments, human relationships, and familiar environments are seized with a precision that goes beyond narrow identity. Saïdou Dicko, with his stylised figures against a symbolic brick background, speaks of individual and plural structures, of

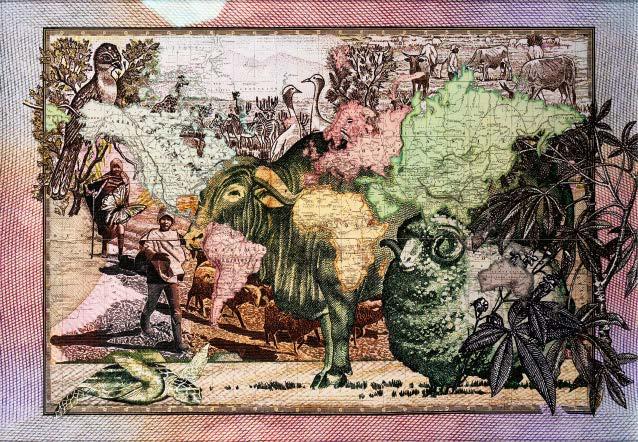

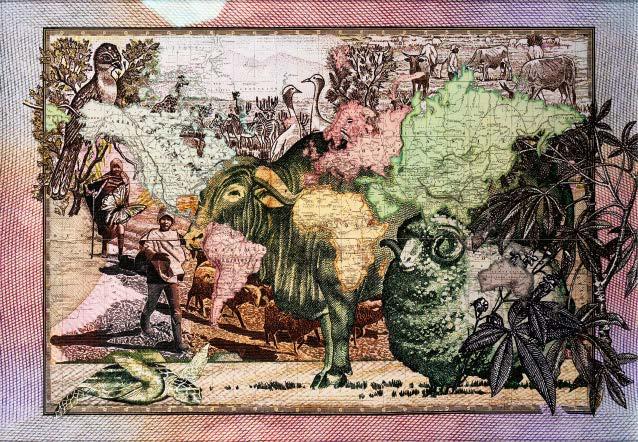

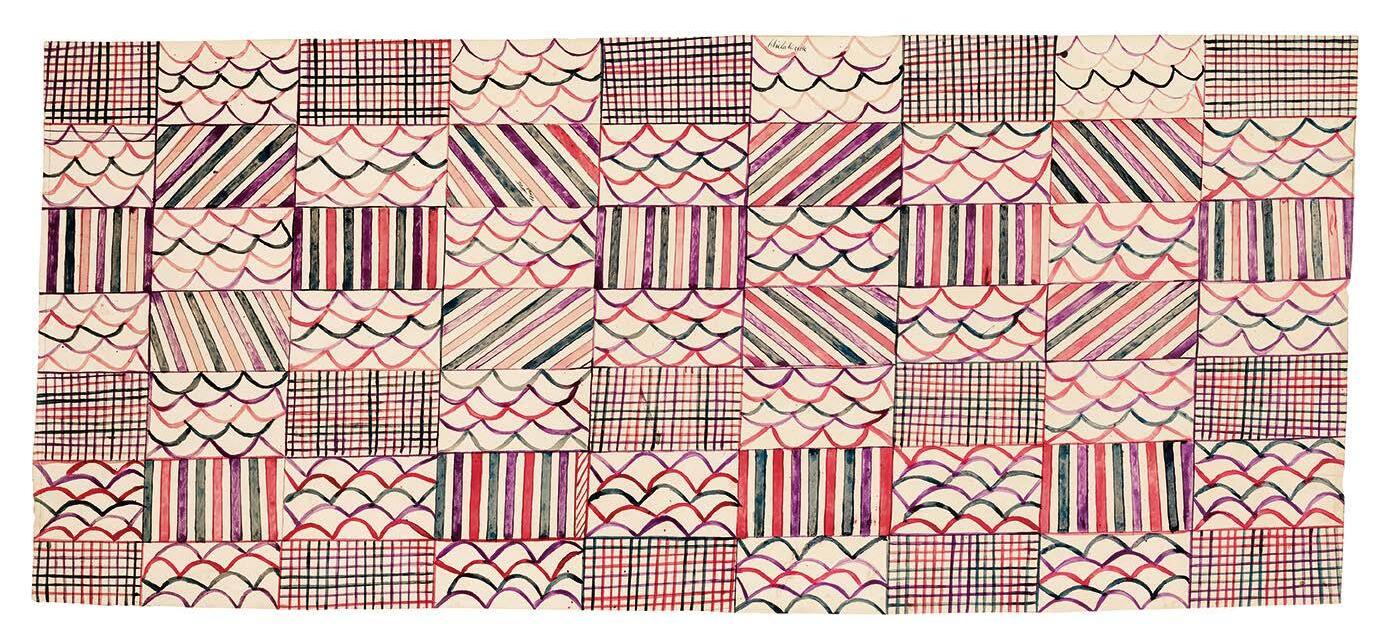

Malala Andrialavidrazana 1971, Antananarivo, Madagascar

Malala Andrialavidrazana is a French-Malagasy visual artist trained in architecture, whose work blends photography, collage, and publishing. Through series such as Echoes and Outre-Monde, she explores themes of memory, identity, and tradition in the context of contemporary societal change. Her work has been exhibited internationally, notably at the Palais de Tokyo, in Bamako, and in Karachi.

Figures 1862, Le Monde – Principales Découvertes 2015 Photomontage. UltraChrome pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Ultra Smooth paper, 110 x 163 cm

© All rights reserved

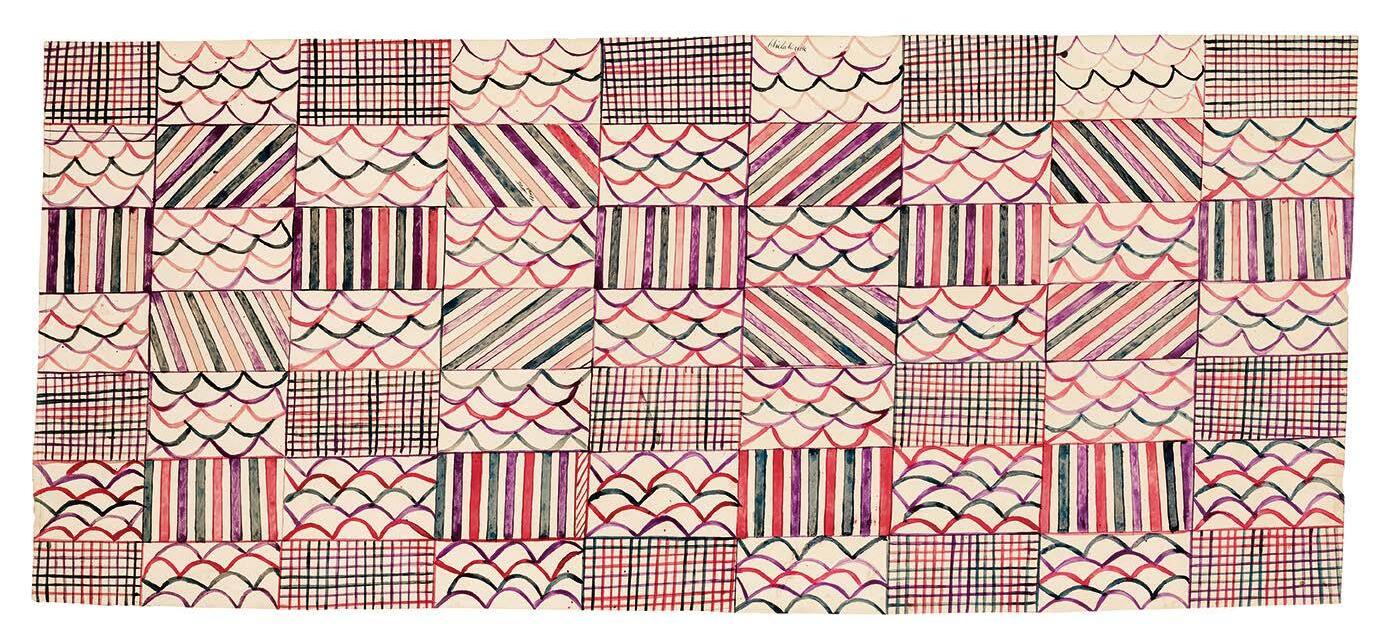

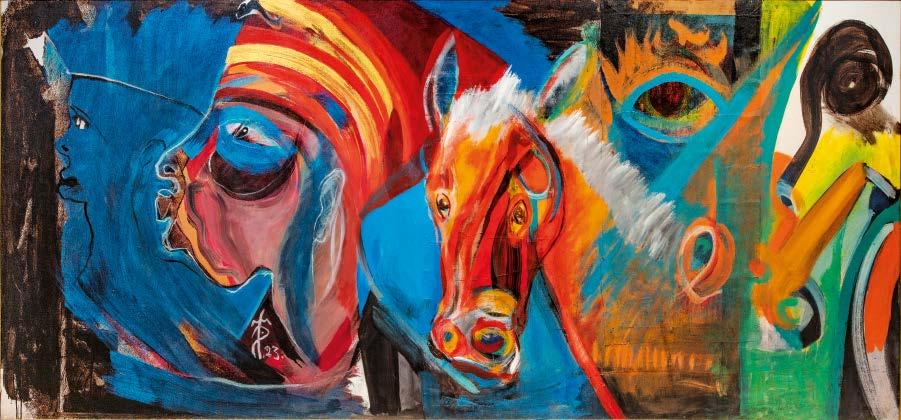

Soly Cissé

1969, Dakar, Senegal

Soly Cissé joined the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Dakar in 1996, an institution with which he maintains strong ties despite now living near Paris. His academic career, enriched by a personal exploration of material and form, has enabled him to forge a powerful visual language deeply rooted in the realities of post-colonial Africa. A polymorphous artist, he moves openly between painting, sculpture, and installation, using these mediums to reveal what the concrete strives to keep hidden.

His compositions, often in large format, are characterised by a vibrant palette combining brilliant colour and earthy tones, creating a striking tension between abstraction and figuration. This approach reflects his intimate connection with the land and African historical narratives. The artist explores the construction and deconstruction of identity, the weight of colonial history, and the aspiration for a new identity freed from external diktats.

Since his first appearance at the Dak’Art Biennale in 1996, Cissé has participated in numerous events, including the Venice Biennale (2000), the Dak’Art Biennale, and the Lubumbashi Biennale (Democratic Republic of the Congo). In 2025, Galerie Chauvy in Paris opened the solo exhibition Soly Cissé, le Monde perdu

Soly Cissé

Offrande I

2018

Acrylic on canvas

100 x 100 cm

© 2025, ProLitteris, Zurich

Cheikh Ndiaye

1970, Dakar, Senegal

Cheikh Ndiaye studied at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Dakar then at the École des Beaux-Arts in Lyon. He divides his time between Dakar and Prague. His work, which encompasses painting, photography, and installation, is distinguished by a particular focus on architecture and urban life, especially the informal and ordinary elements of the environment, which he considers fundamental to his artistic practice. He gives new life to old objects, bringing them out of abandonment and reintegrating them into a new imaginary world.

Among his notable works are paintings depicting urban scenes, often including painted openings in opaque, rough concrete walls, suggesting thresholds or passages. Ndiaye explores the porosity of substances and proposes a notion of disintegration as movement resisting oblivion. His work has received many awards, including the 2012 Nautilus Art Temporary Prize in Berlin, Germany. In 2008, he won the Prix Linossier in France.

In 2017, he was invited by Maréchalerie, Versailles, France, where he presented his monumental installation Hippocampus. In 2018, Brise-Soleils des Indépendances was exhibited at the thirteenth Biennale d’art contemporain de Dakar. In 2024, the Cécile Fakhoury gallery in Paris unveiled Ndiaye’s work in a solo exhibition, Ritz Unité 3.

Cheikh Ndiaye

Le Ouezzin (Marcory)

2017

Oil on canvas

207 x 172 cm

© All rights reserved

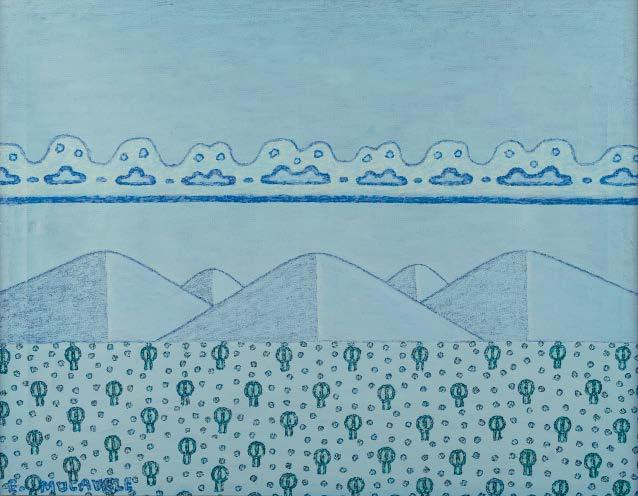

Estevão Mucavele

Untitled

ca. 1989

Oil on canvas

61 x 79 cm

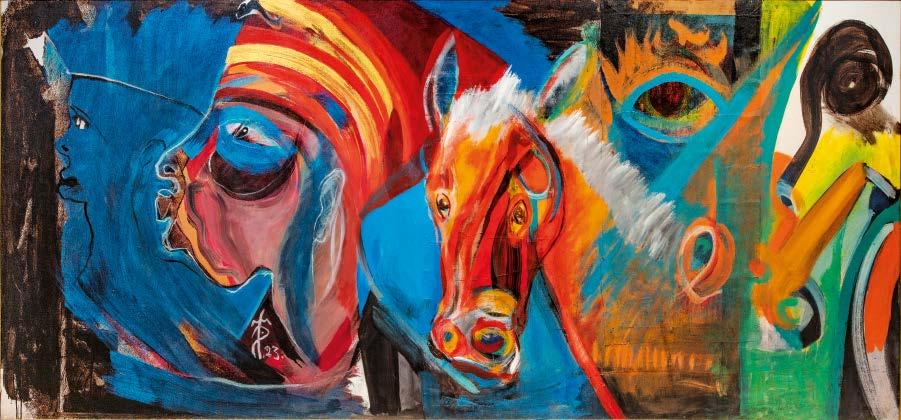

William Kentridge

1955, Johannesburg, South Africa

William Kentridge is a visual artist who graduated in Fine Arts from the Johannesburg Art Foundation. In the late 1970s, he first turned to theater, where he studied mime and dramatic art in Paris. In 1979, he returned to drawing and printmaking and created some thirty monotypes that became the Pit series. The following year, he produced some fifty small-format etchings called Domestic Scenes. These two series established Kentridge’s artistic identity, one he has continued to develop.

His style is characterised by charcoal and ink drawings, often erased and then reworked in a series of successive images to create expressive, poetic, animated films. His work extends beyond the realm of drawing to encompass theater, sculpture, and installation, playing with notions of memory, history, and illusion.

Kentridge is also renowned for his large-scale works. His tapestries, created in collaboration with craftspeople, incorporate his iconic silhouettes, often inspired by South African history and colonialism. Deeply affected by his country’s political and social history, particularly apartheid and its consequences, Kentridge explores themes of oppression, exile, memory, and post-colonial reconstruction. A striking example is Portage (2000), a tapestry featuring cut-out black silhouettes seemingly moving forward in a powerful narrative, evoking exile and displacement.

His murals, meanwhile, mark urban and institutional spaces with striking expressive force. Triumphs and Laments (2016), a giant fresco on the banks of the Tiber in Rome, is the most emblematic example. Composed of mythological and historical figures gradually erased by the passage of time, this work underscores the ephemerality of memory and history.

In 2010, the MoMA in New York dedicated a major retrospective to his animated films and work on paper. In 2018, Tate Modern (London) opened an exhibition exploring his multimedia work and political commitment. In 2020, the Musée LaM in Villeneuve-d’Ascq (France) presented a retrospective of previously unknown works conceived in close collaboration with the Kunstmuseum Basel (Switzerland). In 2025, his exhibition Je n’attends plus, in Arles (France), revealed work never before seen in Europe.

William Kentridge (in collaboration with Greta Goiris) Citizens

2024

Metal, wood, and materials, on pedestal

105 x 45 x 120 cm

© All rights reserved

Our deepest thanks go to all those whose contributions have made this exhibition possible.

In particular, we wish to thank the entire team at the Musée d’art et d’histoire de Genève.

Scenography: Pierre Yovanovitch and Christine Cheng, Atelier Pierre Yovanovitch, Paris

Implementation and Technical Coordination: Atelier Nicolas Perrottet, Geneva

Art Conservation and Restoration: Andrea Hoffmann, Hoffmann Art Management, Geneva

Press Relations:

Cabinet Privé de Conseils S.A., Geneva Art en Direct, Paris

St James Arts, London

Transport and Installation: Henri Harsch SA, Geneva Pedestals: Robin Keller, Geneva

Graphic Design: Kateryna Polishchuk, Maastricht, Photography: Pascal Bitz, Team Reporters, Geneva

French to English Translation: Molly Yakusan Stevens, The Art of Translation, New York

English Proofreading and Editing: Jake Starmer, New York, Nathalie Bijlenga, Geneva, and Lloyd Arrigoni, Geneva

French Proofreading and Editing: Nathalie Bijlenga, Geneva, and Lloyd Arrigoni, Geneva

A special thanks to:

Viviana and Jo Benhamou, whose passion for art and deep personal commitment inspired the creation of the collection.

Abdoulaye Camara, cornerstone of all artistic and heritage collaboration in Dakar.

Joëlle Thibet-Marin for her invaluable advice, both for the catalogue and the exhibition.

Section Texts Authored by: Ousseynou Wade

Catalogue Entries Authored by: Jean-Yves Marin, with the kind collaboration of the artists and partner galleries.

5 CONTINENTS EDITIONS

Editor-in-Chief

Aldo Carioli

Art Director

Oliver Barstow

Editor

Lucia Moretti

Proofreading

Jennifer Coe

Pre-press

Maurizio Brivio, Milan, Italy

All rights reserved

© CBH Compagnie Bancaire Helvétique SA

For the present edition

© 2025 CBH Compagnie Bancaire Helvétique SA & 5 Continents Editions S.r.l.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher

5 Continents Editions

Piazza Caiazzo, 1 20124 Milan, Italy www.fivecontinentseditions.com

ISBN 978-88-7439-486-9

Printed on Munken Polar 170 gr paper and bound in Italy in September 2025 by Tecnostampa – Pigini Group Printing Division Loreto – Trevi, Italy for 5 Continents Editions, Milan

Distributed by ACC Art Books throughout the world, excluding Italy. Distributed in Italy and Switzerland (Canton Ticino) by Messaggerie Libri S.p.A. Distributed in France and French-speaking countries by BELLES LETTRES / Diffusion L’EntreLivres.

Front cover:

Amadou Sanogo, Le Frimeur, 2021, Acrylic on canvas, 244 x 160 cm © Amadou Sanogo