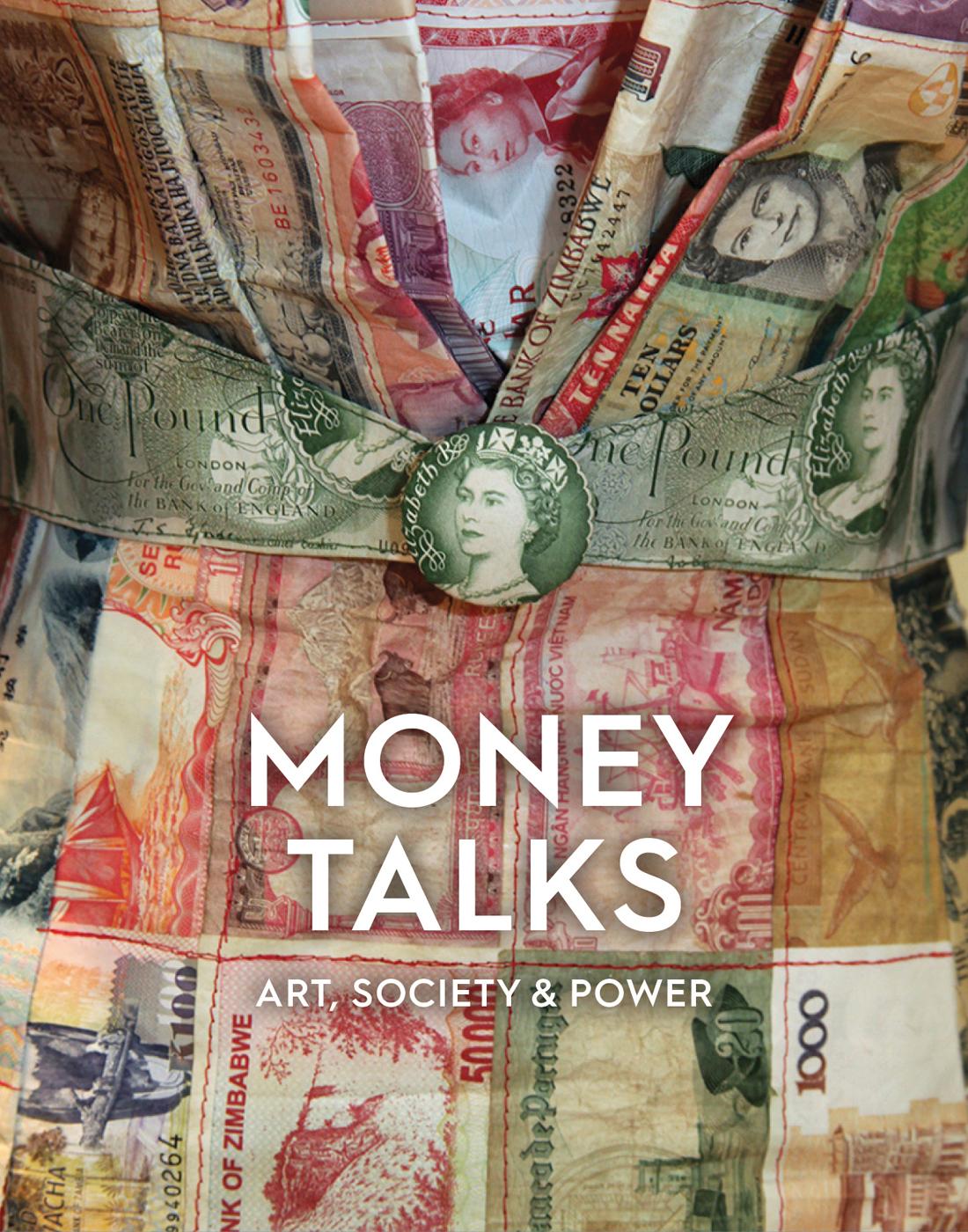

Money Talks: Art, Society & Power 9 August 2024 to 5 January 2025

Copyright © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, 2024

Shailendra Bhandare, Joe Cribb, Graham Dyer, Shreya Gupta, Michael Gründner, Richard Kelleher, Sydney Smith, Foteini

Valeonti and Matthew Winterbottom have asserted their moral rights to be identified as the authors of this work.

British Library Cataloguing in Publications Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978-1-910807-62-0

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any storage and retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Edited by Lizzy Silverton

Catalogue designed by Stephen Hebron

Printed and bound in the UK by Gomer Press

Frontispiece: First set of definitive coins of King Charles III, 2023, United Kingdom. Photo: Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. Courtesy Shailendra Bhandare.

For further details of Ashmolean titles please visit: www.ashmolean.org/shop

Exhibition supported by:

Mr Barrie and Mrs Deedee Wigmore

The Patrons of the Ashmolean Museum

Mr E. Penser

We are most grateful to all our lenders who are supporting our exhibition:

The Royal Mint Museum

Collection Banque de France

Money Museum of the Austrian National Bank (Österreichische Nationalbank)

National Portrait Gallery, London

Tate

De La Rue

Victoria and Albert Museum

The Trustees of the British Museum

New College Oxford

Corpus Christi College Oxford

Jesus College Oxford

The National Gallery, London

The Postal Museum

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Collection Dr Robert B. Feldman

Baptist Coelho

Martin Jennings

Chris Levine Studio

Martín Nadal and César Escudero Andaluz

Courtesy Grayson Perry, Paragon | Contemporary Editions Ltd and Victoria Miro

Stephen Sack

Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg/Amsterdam

Courtesy Susan Stockwell & Patrick Heide Contemporary Art

Courtesy Larva Labs

Courtesy Rare Pepe Foundation

Courtesy Sarah Meyohas

Courtesy Alex Estorick and Ana Caballero

Joe

King Edward VIII and the Coinage that Never Was

Graham Dyer

‘Numismatibus ornatum’: The Decorative Use of Ancient 51 and Modern Coins on Renaissance and Baroque Silver

Matthew Winterbottom Manifest Munificence: Forms and Features of Goddess

Shri Lakshmi in Art and on Money

Shailendra Bhandare

‘So little appeal …’ : Austrian Banknotes of the Fin de Siècle

Michael Gründner

– Art –

Richard

a Continent: Banknote Art in Colonial Africa

Shailendra Bhandare

Coin of the Realm: Contemporary Money-Art

in Global Circulation

Sydney Smith

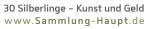

Kingdom and their ambivalent relationship (fig.8).58 She gave two representative figures the money symbols as hair, showing them about to kiss with their eyes closed and drawing back in shock when they open their eyes and recognise the reality of their relationship.

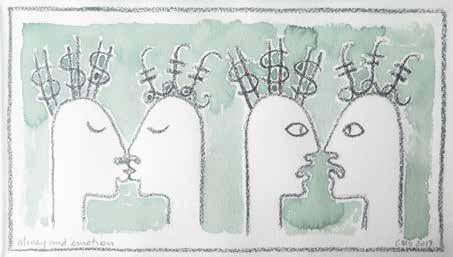

An actual coin is the subject of Stephen Sack’s photograph, Euro Mask. Photographic artist Stephen Sack has long had an interest in creating images of worn and corroded coins and other forms of money.59 This piece (fig.9), formed from a twenty-cent euro piece, is one of his series of Euro Masks, and complements another of his series, Euro Meltdown. All the coins in these series have been damaged while being burnt with rubbish. Sack rescued them from the garbage incinerator, an act of what he terms ‘future archaeology’, and has used them to create these two series of mysterious images. This example has been melted into a face, which seems to express the distress of the euro crisis of 2009–17, when the fragile economies of Greece, Ireland, and Portugal all faced the possibility of damaging the euro monetary system. Sack’s recent intervention, using ancient dolphin-shaped coins from the Black Sea region, titled Creatures of the

Cat.97 Bank of England 10-pound note defaced with a rubber stamp featuring Marie Stopes, designed and applied by Paula Stevens-Hoare, 2014, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.8 Money and Emotions, Erica Steenkamp, 2019

Black Sea, makes a powerful statement against the war in Ukraine, tapping on the multi-layered association of the imagery he creates (cat.111).

Each of these artists has responded to the aesthetic and symbolic value of monetary objects in different ways as part of the modern movement of creating money-related art. This phenomenon has been examined in detail by the neo-Marxist commentator Max Haiven, particularly the ways in which artists have responded to the relationship between money and art, both as an appealing topic for wealthy art collectors, as well as a protest against the corruption of art by money and of society by their combination.60 In the five works detailed above many strands of intent can be discerned: protest, satirical commentary, and a pure joy in the aesthetic qualities of monetary forms, designs, and traditions. What is clear is that they approach the relationship between art and money in a playful and visually engaging way, each artist bringing value out of this relationship, even though barely bringing any money into their pockets.

Money and art as synonymous metaphors

Barely a week goes by without the news telling us of another record price paid for a work of art. In the popular mind, art has become synonymous with money; a metaphor for disposable wealth. The art being acquired at such high prices

Above: Fig.9 Euro Mask, Stephen Sack, 2017

Below: Cat.111 Creatures of the Black Sea, Stephen Sack, 2022, Private collection

‘So little appeal …’ Austrian Banknotes of the Fin de Siècle

Michael Gründner

Unfortunately, these sketches … are so one-sided and have so little appeal that one can neither accept them nor encourage the gentlemen to draw new ones.81

This unflattering verdict was not directed at a pair of amateur street artists, or at draughtsmen new to their craft, but at two artists who had already made a name for themselves in late nineteenth-century Vienna: Gustav Klimt (1862–1918) and Franz Matsch (1861–1942). And they were not the only prominent artists who found themselves rejected by the same client. Ten years later, Koloman Moser (1868–1918) and Josef Hoffmann (1870–1956) fared little better with a similar project. But which works of art prompted such a harsh verdict? And who presumed to pass this judgment on some of the leading artists of the fin de siècle?

Before we dive into answering these questions, a short digression into the background of the Art Nouveau movement in Austria is required.

Art nouveau

The international art phenomenon Art Nouveau, or Jugendstil in German, which emerged at the turn of the nineteenth into the twentieth century, had numerous centres. In German-speaking countries these were Munich, Darmstadt, and notably Vienna. The latter was the capital of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and an economic, political, social, and cultural hub, making it a magnet for intellectuals and artists alike. In this city, they found inspiration, mingled with like-minded people, and hoped to reel in new commissions. With the advent of the industrial revolution in the mid-nineteenth century, the opportunities to land a job increased, with bourgeois families competing with the traditional elites of the imperial court, the nobility, and the church to flaunt their newfound wealth. The upper middle class was often more open-minded towards modern ideas than the elites of the old order, thus offering aspiring artists the opportunity to break new ground.

In April 1897, led by Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Josef Hoffmann and Joseph Maria Olbrich (1867–1908), several avant-garde Austrian artists left the conservatively oriented Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens (Association of Austrian Artist). They founded the Vereinigung bildender Künstler Wiener Secession (Association of Visual Artists Vienna Secession) – thus the Viennese Jugendstil is also called the Vienna Secession – and became the forerunners of Art Nouveau in Austria. The Secessionists broke away from the overloaded and

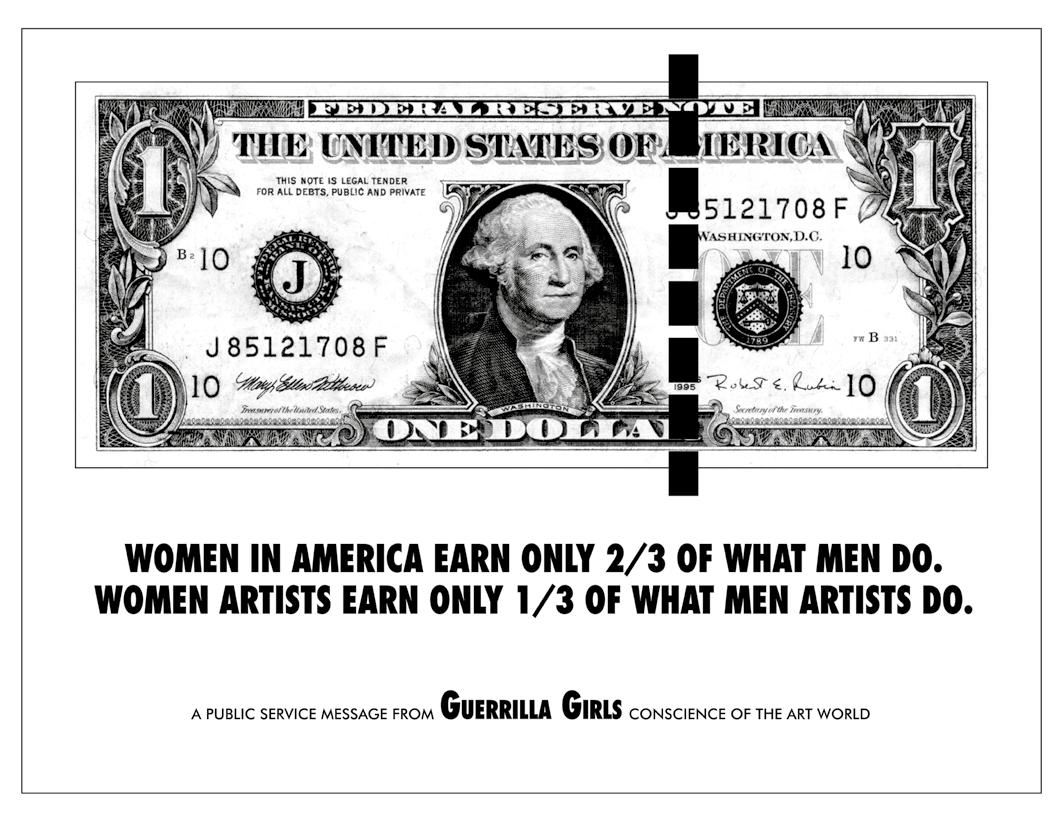

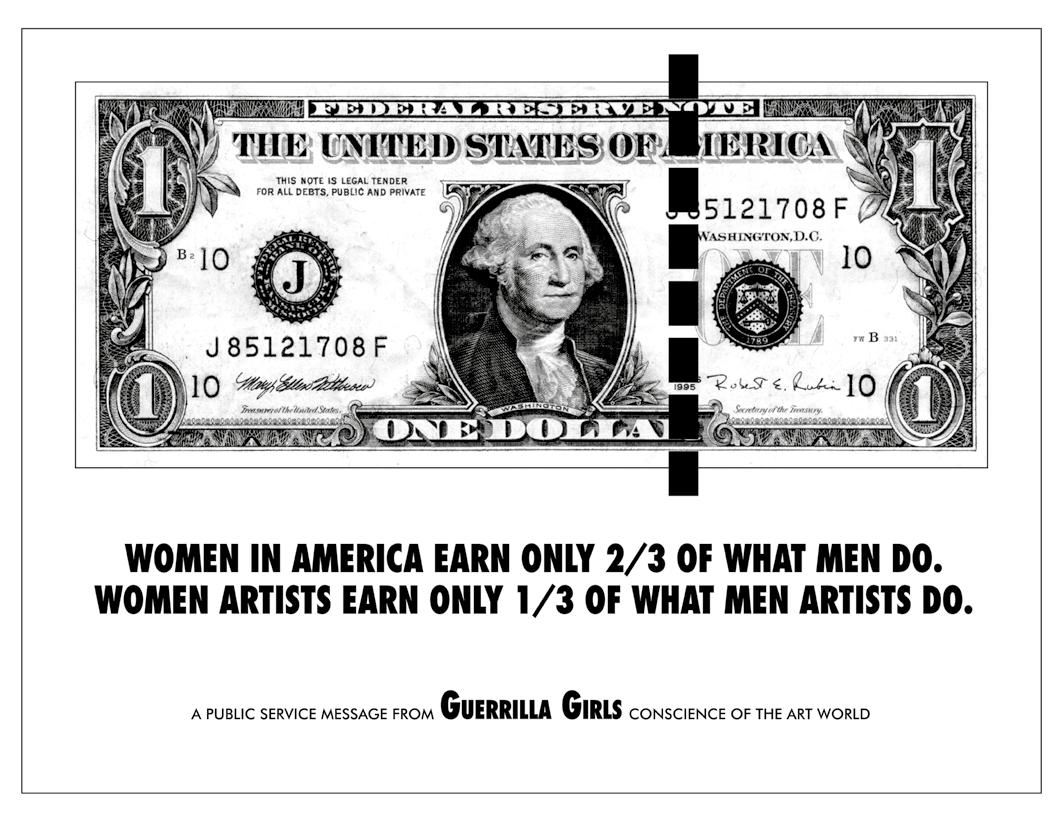

a perforated line separating a detachable seven and a half cent section – the message being that the Diefenbaker Government had caused the Canadian dollar to devalue against its US counterpart to this degree. This form of visual trope was central to the Guerilla Girls’ protest piece on equal pay for women. The groups’ accusatory graphic activism of the late 1980s and early 1990s used damning statistics to make their point and mark moments of protest against the oppression and marginalisation of women. In their classic infographic style, the 1985 piece, Women in America Earn Only 2/3 Of What Men Do (cat.98) uses the simple conceit of taking a well-known everyday object – a one-dollar bill – and adding a dotted line. This clever arrangement read from left to right illustrates the disparity in earnings between men and women in the US, and read from right to left shows the disparity regarding the earnings of women artists against their male counterparts.

As the self-appointed ‘conscience of the art world’, the Guerilla Girls continue to point out the mutually determining forces of sexist and racist structures in art exhibitions and theory.135 Coins too have been used to make the point about equal pay for women. Taking inspiration from the ‘Votes for Women’ stamped

Cat.98 Women in America Earn Only 2/3 Of What Men Do, Guerrilla Girls, 1985, Tate, London

pennies of the early twentieth century, and the 2010 film Made in Dagenham, Paula Stevens-Hoare defaced contemporary 50-pence pieces to highlight the gender pay gap (fig.43).

Other monetary interventions include The Pay Gap Pound, which was developed by the advertising agency Mr President and the creative network SheSays as part of the Equal Pay Day Campaign. The convincing imitations, called The Pay Gap Pound, were created to remind people that on average women earn just 82 pence for every pound earned by men. Equal Pay Day in the UK falls on 20 November as it is from this day until the end of the year that women essentially work for free. Money is a powerful medium to use when highlighting inequality in pay, but another aspect of gender inequality is in who is represented on banknotes. Notable Women by Paula Stevens-Hoare is a series of ten-, twenty-, and 50-pound notes over-stamped in response to the discontinuation of the five-pound note featuring Elizabeth Fry – the only woman represented on the back of a Bank of England note. This imbalance is found globally, with just fifteen per cent of world banknotes featuring images of women. Using stamps and different colour inks Stevens-Hoare chose notable women to replace the males on the reverses; Marie Stopes (1880–1958) for Charles Darwin (1808–1882) on the ten-pound note, Rosalind Frankin (1920–1958) for Adam Smith (1723–1790) on the twenty-pound note (cat.97) and Sarah Guppy (1770–1852) and Tilly Shilling (1909–1990) for Matthew Boulton and James Watt (1736–1819) on the 50-pound note.

Fig.43 50-pence coin stamped ‘EQUAL PAY FOR WOMEN’, Paula StevensHoare, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Cat.97 Notable Women: Rosalind Franklin, Paula Stevens-Hoare, 2014, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

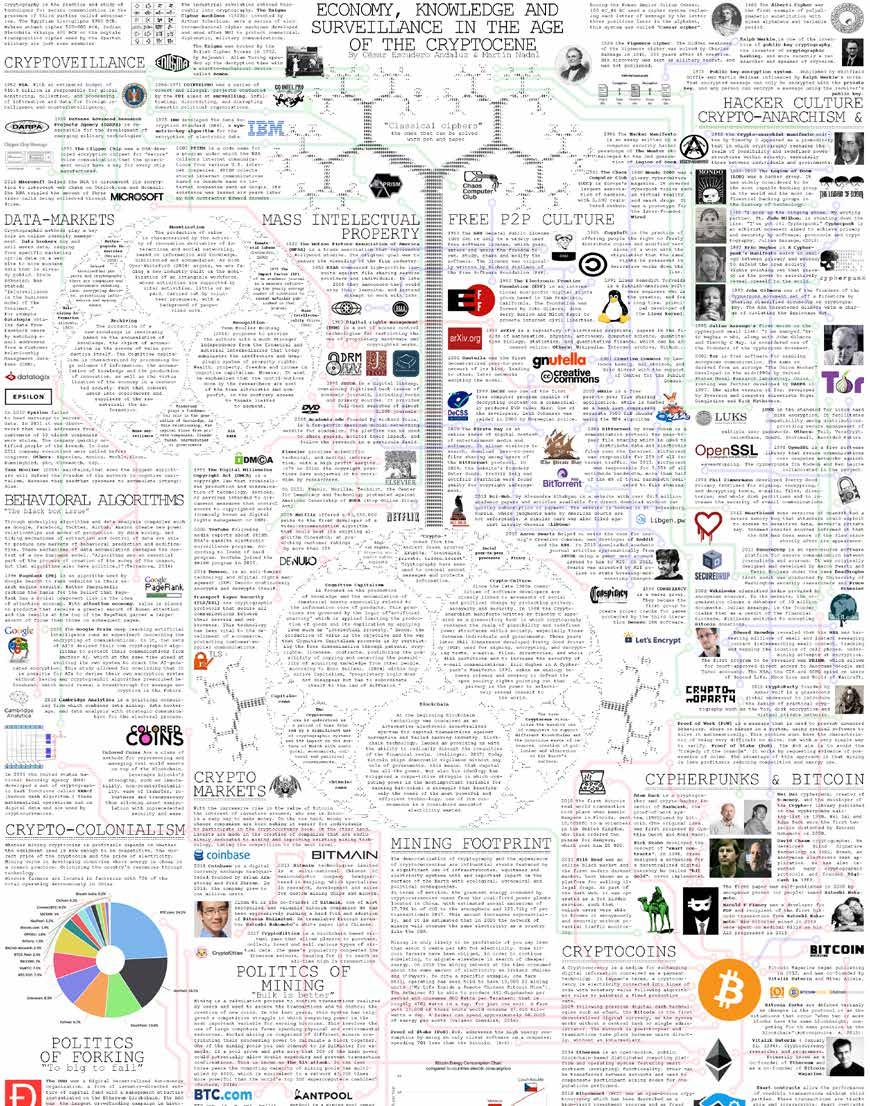

Opposite: Cat.113 Economy, Knowledge and Surveillance in the Age of the Cryptocene, Martín Nadal and César Escudero Andaluz, 2018

Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs), Money, and Art

Foteini Valeonti

In recent years, a new medium has emerged at the meeting point of art and money. NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens), or crypto collectibles, attracted the attention of mainstream media in March 2021 when a NFT by digital artist Mike, also known as Beeple, was auctioned at Christie’s for 69 million dollars.166 Titled Everydays: The first 5000 days, it featured a digital image depicting a collage of 5,000 individual artworks. Although it was the first ‘purely digital artwork (NFT) ever offered at Christie’s’, it was not the artist’s first NFT artwork to be sold for millions.167 A month earlier, in February of that year, Beeple’s piece CROSSROADS was sold for 6.6 million dollars, whereas the month prior, in December of 2020, Beeple’s NFT sales exceeded three million dollars.168 Following the meteoric rise of NFTs in early 2021, curious members of the growing NFT community started exploring the potential of this new medium just as skeptics were pointing out the technology’s flaws. At the time, the environmental impact of NFTs was arguably their greatest weakness, and was inherited from Ethereum, the blockchain network where NFTs were invented and where the vast majority of them are still traded. Until the Autumn of 2022, Ethereum’s energy consumption was indeed substantial. However, a major technological upgrade of Ethereum on 15 September 2022, known as ‘The Merge’, dramatically reduced the blockchain’s energy consumption, and subsequently that of NFTs to the levels of standard computing.169 Yet, criticism of NFTs remains fierce, reflected in articles examining ‘why do people hate NFTs so much’.170 Exploring the medium’s strengths and weaknesses, which have been evolving over the last few years, this essay aims to contribute to the ongoing debate surrounding NFTs, focusing on the convergence of crypto collectibles, culture, and money.

What is an NFT?

NFTs are a new medium that introduces digital scarcity, enabling uniqueness of objects and ownership in the digital realm. Crypto collectibles are utilised in multiple industries, from finance and logistics to sports and gaming.171 In the context of culture, NFTs can be described as the digital equivalent of limited editions, whereby the print copy is substituted with a digital copy (e.g. a JPEG image) and the signature is not a physical one but a digital one ciphered on the blockchain.172 The key difference between limited editions and NFTs, however, is that whereas the former rarely compete in value with paintings or sculptures, NFTs have the potential to do just that. Indeed, Beeple’s Christie’s auction ranked as the third highest in history by a living artist, surpassing Gerhard Richter (b.1932), as well as most auctions by famous Old Masters, including Raphael (1483–1520) and

Cat.63

Queen Elizabeth II (‘Equanimity’), 2012

Chris Levine (b.1960) and Robert Munday (b.1958)

Rosaline Wong Gallery, Jesus College and HomeArt

This portrait of Queen Elizabeth II (1926–2022) by the Canadian artist Chris Levine and holographer Robert Munday, of UK company ‘Spatial Imaging’ was specially commissioned in 2004 by the States of Jersey and the Jersey Heritage Trust to commemorate 800 years of Jersey’s allegiance to the Crown. In later years it was used to commemorate other events related to the queen’s long reign. In 2012, it featured on a commemorative 100-pound banknote marking the queen’s Golden Jubilee. Equanimity, is the first officially commissioned holographic-stereographic portrait of the queen, or of any member of the royal family.

Director of the Jersey Heritage Trust, Jonathan Carter, commented of the commission:

As Jersey has a long and fascinating relationship with The Crown, we wanted to commission a Royal Portrait that not only reflects this history but is also a contemporary iconic image of distinction. By presenting our heritage in this contemporary form, the portrait will symbolise and celebrate Jersey, its people and the future.

Light is central to the works of photographer Chris Levine. He suggested that the holographic stereogram be lit with blue light to enhance the sense of ‘equanimity’ – the ‘quality of being calm and even tempered’. Robert Munday is a pioneer in holography and lenticular imaging. In 1985, Munday set up the world’s first post-graduate degree in creative holography at the Royal College of Art, and created some of the first computergenerated holographic stereogram artworks.

The three-dimensional portrait was the result of two sittings at Buckingham Palace in November 2003 and March 2004, which together lasted for around two and a half hours. During this time approximately 8,000 images of the queen were made. The camera would need to reset for about eight seconds after each pass and Levine advised the queen to rest her eyes in these moments. Another ethereal image of the queen, the Lightness of Being, which shows her with her eyes closed, was produced years later from the images taken when she was resting between the many shots.

These photographs were taken using a specially designed 3D camera system, with a moving camera that could take a series of captures from different positions. The ‘Video Images with Parallax’, or ‘VIP’, system was used to record the parallax image sequences, from which the holographic stereogram portrait was created. After the second sitting, Munday chose one of the parallax image sequences, which was then enhanced, to give way to the final portrait.

148 money talks

It was Munday’s decision to go with a simple and realistic portrait to emphasise the queen’s majesty and to create the impression of meeting, or knowing, her when looking into her eyes. Levine chose her outfit – a dark blue velvet dress, a single string of white pearls, and the George IV (1762–1830) Diamond Diadem, on recommendation from Buckingham Palace. The diadem was made for the coronation of George IV in 1820 and was subsequently worn by Queen Victoria (1819–1901) and Queen Elizabeth II at their coronations. Munday suggested using a white cape and the Personal Assistant and Dresser to The Queen came up with an appropriate selection. From this emerged the famed ‘hologenic’ white ermine stole that can be seen in the portrait.

The final print consisted of a lenticular 3D stereogram, which was printed in Munday’s holography studio. It was unveiled by the then Prince Charles at Mont Orgueil Castle in St Helier, Jersey, where it remains as part of the permanent collection. Another lenticular image was depicted on limited edition gold and silver medals issued by the Royal Mint to mark the queen’s eightieth birthday. Many more versions of Equanimity have since been created and displayed at other venues. In 2011, the Jersey Post commissioned Munday to create a portrait for a stamp marking the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee. These stamps were the world’s first to have a threedimensional holographic portrait of a head of state on them.

Queen Elizabeth II was one of the most photographed and painted figures. Her image is familiar worldwide, largely through money that bears her portraits. No less than 33 issuing authorities the world over have issued banknotes with her image and there are 31 different ‘monetary’ portraits showing her in different stages in her long life. This makes the late Queen one of the most recognisable faces in the world.

Further reading:

Munday, Robert, ‘Queen Elizabeth II: The Jersey Heritage Trust –The States of Jersey royal portrait commission’, undated, https:// www.rob-munday.com/portraits-of-queen-elizabeth-ii [accessed 22 August 2023].

Munday, Robert, ‘The history of the hologram portrait miniatures of Her Majesty the Queen by Rob Munday’, November 2019, https://www.rob-munday.com/_files/ugd/ a8f420_182b4ddfb5264dad98773d4a986d1b4e.pdf [accessed 22 August 2023].

‘Artist Chris Levine on How He Turned a Portrait Session With Queen Elizabeth II Into an Iconic Photograph’, artnet, 9 November 2022, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/chris-levine-interviewqueen-elizabeth-2203261 [accessed 17 April 2024].

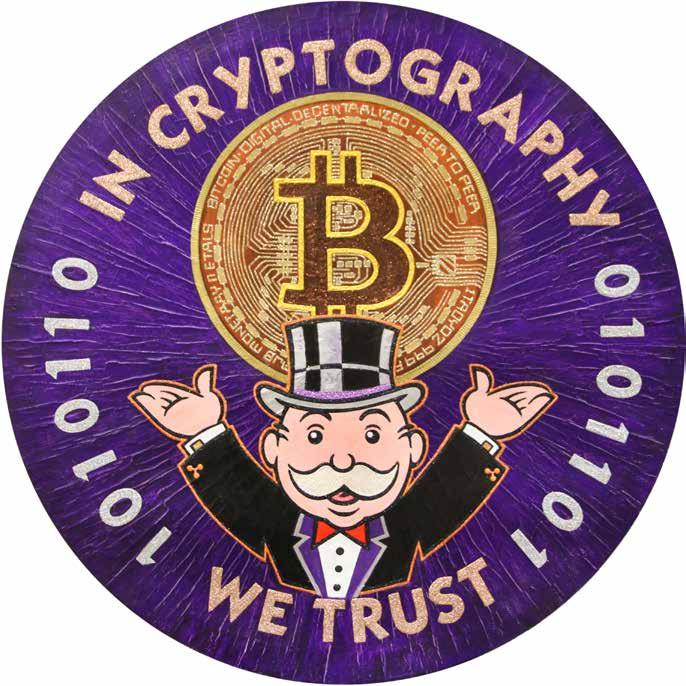

Cat.112

In Cryptography We Trust, 2017 Alexander C. Cornelius (b.1969) Sammlung Haupt

This work, commenting on cryptocurrency, is part of the 2017–19 series, The Adventures of Rich Uncle Pennybags, consisting of 25 artworks made by the painter Alexander C. Cornelius. Each piece is designed in the shape of a coin or medal. Around the canvas, each work carries a twist on a quote, song, or reference, given in German, Latin, or English, surrounding an image of the famous figure from the board game Monopoly, Milburn Pennybags, also known as ‘Rich Uncle Pennybags’. The series deals with various themes related to money, including greed and capitalism, and their relation to art, the art market, and the value of money in society. Through the work In Cryptography We Trust, the artist takes up the theme of cryptocurrency, with a Bitcoin drawn at centre. With sarcasm and humour, he comments on the interest cryptocurrency has generated and its sociocultural impact on society.

Cornelius was born in 1969 in Sterkrade, Germany. He studied communication design at the Folkwang University of Arts in Essen and was a student of Jörg Immendorff at the Art Academy in Düsseldorf. In his school days, during the early 1980s in West Germany, board games were a part of Cornelius’s daily life and among them Monopoly was his favourite. Later, in 2015, Cornelius noted that McDonalds ran a Monopoly lottery around Christmas each year, with the figure of Milburn Pennybags featuring heavily. This indicated to him that the character was still alive in the public imagination and widely recognised, leading to the idea of having him as a central protagonist for the series.

The character of Milburn Pennybags first appeared in 1936, complete with a top hat, tuxedo, cane, and a big white moustache. The designer of the character, Daniel Fox, derived inspiration from the calling cards he had made for Parker Brothers, the manufacturers of the game. These featured the character ‘Little Esky’, who appeared on the cover of Esquire, the top men’s magazine of the era, which ran Parker Brothers advertisements. Little Esky, in turn, was modelled after the American businessman J. P. Morgan.

It wasn’t until 1946 that the character gained a name, initially being referred to as ‘Rich Uncle Pennybags’ as he also appeared on the lid, instructions, and currency of the board

game Rich Uncle. However, he was more widely known as ‘the Monopoly Man’, hence his name was changed to ‘Mr Monopoly’ in the 1990s. The Forbes fictional list even listed him as the sixth richest fictional character in 2006.

Seen in Cornelius’s work, with his familiar moustache, morning suit, bow tie, and top hat, Mr Monopoly has a comic book-like identity and nostalgic air, which makes it easy for the viewer to enjoy the playful nature of the series. But as the message of words that surround him sink in, the seriousness of the themes the artist is commenting on become clear. Pieces in the series feature lyrics including ‘Life is a cabaret old chum’ from Cabaret as well as quotes such as ‘Greed is Good’ from the film Wallstreet. Others depict popular sayings like ‘Time is Money’ and ‘Money Makes the World go Round’. The words of poets including Oscar Wilde (1854–1900), and famous quotes by Roman emperors and popular artists can also be found as inscriptions.

The series is painted in bright solid colours, a characteristic of Cornelius’s work that reflects his love of bright, ‘flashy’ tones. He also likes to use metallic effects in his work, something that he started working with during the 1980s and continues in this series. He bought his first large round canvases, like the one used in this piece, in a shop in Düsseldorf’s old town. He first printed them with silvercentred rays and painted one with a pearlescent dark blue colour. He wasn’t sure of what motif to use until he heard the soundtrack of the film Cabaret and used the quote ‘Money Makes the World Go Round’ for one of the pieces in the series. Showing popular quotes, bright colours, comic-book aesthetics, and the figure of Mr Monopoly, the pieces make for eye-catching works.

Further Reading:

‘New in the Sammlung: In Cryptography We Trust, Alexander C. Cornelius’, Sammlung Haupt, November 2021, https:// files.artbutler.com/file/1110/3658d8af32fe44c6.pdf [accessed 8 September 2023].

Orbanes, Philip E., Monopoly: The World’s Most Famous Game –and How It Got That Way (London, 2007).

45 [EX25.083]

Plaster cast of a portrait head of Nero (r.54–68) from the Palatine Hill, Rome, early 20th century

450 mm (height)

Ashmolean Museum, CG.B .166

46 [EX25.065]

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

Profile heads of Vitellius, Otho, Nero and Vespasian; all wearing a laurel wreath, 1600–8

Pen and brown ink

Trustees of the British Museum

47 [EX25.116a-c]

Gold Aureus, silver denarius and bronze sestertius of Nero (54–68), Rome mint

19 mm (diameter), Ashmolean Museum, Deposited by Christ Church, 1940. HCR 9404

17 mm (diameter), Ashmolean Museum, HCR 88572

36 mm (diameter), Ashmolean Museum, Bequeathed by Francis Douce, 1834. HCR 21259

48 [EX25.116d-f]

Gold Aureus, silver denarius and bronze sestertius of Galba (r.68–69), Rome mint

20 mm (diameter), Ashmolean Museum, Deposited by Keble College, 1934.

HCR 88893

17 mm (diameter), Ashmolean Museum, HCR 88892

34.5 mm (diameter), Ashmolean Museum, HCR 21359

49 [EX25.116i-k]

Gold Aureus, silver denarius and bronze sestertius of Vitellius (r.69), Rome mint

19.6 mm (diameter), Ashmolean Museum, Deposited by Keble College, 1934.

HCR 89017

17 mm (diameter), Ashmolean Museum, HCR 89032 34 mm (diameter), Ashmolean Museum, HCR 21411

50 [EX25.116l-n]

Gold Aureus, silver denarius and bronze sestertius of Vespasian (r.69–79), Rome mint

19.7 mm (diameter), Ashmolean Museum, Deposited by Keble College, 1934.

HCR 89143

19 mm (diameter), Ashmolean Museum, HCR 89190

32 mm (diameter), Ashmolean Museum, Deposited by New College, 1907.

HCR 21513

of objects

Fig.37 Photo: © Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Fig.38 Photo: © Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Fig.39 © Genpei Akasegawa. Courtesy of Ms. Naoko Akasegawa and SCAI THE BATHHOUSE

Fig.40 © Boo Whorlow. Photo: © Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Fig.41 Photo: © Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge. © Wankers of the World

Fig.42 Photo: © Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Fig.43 Photo: © Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge. © Paula Stevens-Hoare, 2018

Fig.45 Adalbert von Rößler / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Fig.47 Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

Fig.48 Encapsulated banknote images courtesy of Paper Money Guaranty (PMG)

Fig.49 Banque de France

Fig.50 Banque de France

Fig.51 Banque de France

Fig.52 Banque de France

Fig.53 Banque de France

Fig.54 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.55 Encapsulated banknote images courtesy of Paper Money Guaranty (PMG)

Fig.56 Encapsulated banknote images courtesy of Paper Money Guaranty (PMG)

Fig.57 Encapsulated banknote images courtesy of Paper Money Guaranty (PMG)

Fig.58 Encapsulated banknote images courtesy of Paper Money Guaranty (PMG)

Fig.59 Encapsulated banknote images courtesy of Paper Money Guaranty (PMG)

Fig.60 Encapsulated banknote images courtesy of Paper Money Guaranty (PMG)

Fig.61 Encapsulated banknote images courtesy of Paper Money Guaranty (PMG)

Fig.62 Encapsulated banknote images courtesy of Paper Money Guaranty (PMG)

Fig.63 Heritage Auctions / HA.com

Fig.64 Encapsulated banknote images courtesy of Paper Money Guaranty (PMG)

Fig.65 Encapsulated banknote images courtesy of Paper Money Guaranty (PMG)

Fig.66 Image courtesy of Dr Foteini Valetoni

Fig.67 Image courtesy of Cure Parkinson’s

Fig.68 © John Watkinson, Matt Hall; Photo: ZKM | Zentrum für Kunst und Medien Karlsruhe, Photo: Elias Siebert

Fig.69 Gartner, Hype Cycle for Emerging Technologies, 2021, Burke, B., Davis, M. and Dawson, P.

200 money talks