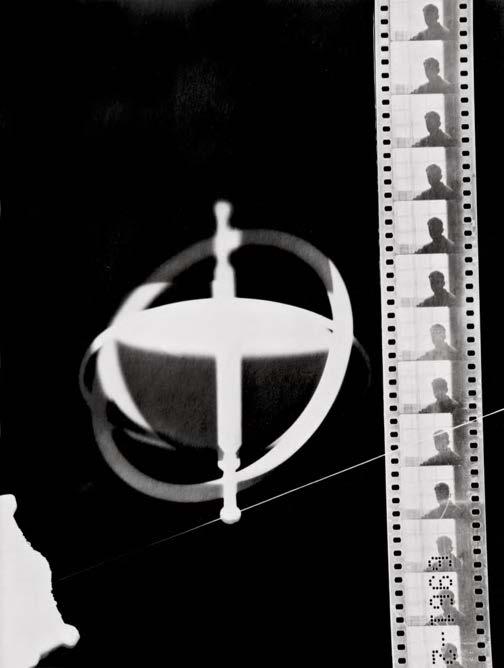

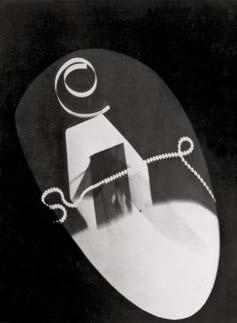

gono una manifestazione della loro estetica e della loro filosofia, un’esplorazione dell’inconscio e del sogno. Nel dicembre dello stesso anno, Man Ray pubblica un album dal titolo Champs délicieux, con prefazione di Tristan Tzara. Composto da dodici rayografie, rappresenta un momento chiave nella storia dell’arte capace di illustrare il connubio tra innovazione tecnica e visione artistica d’avanguardia. Man Ray utilizza lo stesso procedimento per il suo film Le Retour à la raison. Con grande urgenza, improvvisa un cortometraggio che Tristan Tzara desidera proiettare prima della rappresentazione della sua opera teatrale Le Cœur à gaz. Se il film – proiettato subito dopo la realizzazione nella soirée Cœur à barbe – provoca uno scandalo, rappresenta anche l’ingresso di Man Ray nel mondo del cinema d’avanguardia. Seguiranno Emak Bakia nel 1926, un “cinepoema” di ventidue minuti, poi L’Étoile de mer, girato nel 1928, ispirato a una poesia letta dal suo amico Robert Desnos (fig. 4). Les Mystères du château du Dé, del 1929, che mette in scena gli invitati a villa Noailles costruita da Robert Mallet-Stevens, è l’ultimo film di Man Ray. Ancora oggi, le sue opere cinematografiche restano un punto di riferimento. Il primo contatto di Man Ray con l’ambiente della moda avviene grazie allo stilista Paul Poiret, che gli viene presentato nel 1922 da Gabrièle Buffet, la moglie di Picabia. Celebre per aver rivoluzionato la moda, Poiret è anche un appassionato di arte e un importante collezionista. Man Ray, che era andato a mostrargli i suoi ritratti, si lascia convincere dallo stilista a lanciarsi nella fotografia di moda. Grazie al suo sguardo inedito e artistico sulla donna e i suoi abiti, Man Ray rivoluziona la fotografia di moda che stava facendo i primi passi. I suoi esperimenti e la sua creatività, carichi di libertà e senso dell’umorismo, ne faranno un precursore (cat. 204).

Nell’estate del 1929, Lee Miller ha ventidue anni quando arriva a Parigi per imparare a fotografare da Man Ray. Si stabilisce nel suo atelier e diventa la sua assistente, la sua musa e la sua amante. Riscoprono insieme il principio della solarizzazione, conosciuto come “effetto Sabatier”, che consiste nell’esporre parzialmente o totalmente un’immagine alla luce durante lo sviluppo, creando così contrasti insoliti e contorni accentuati. Pur essendo nota dal 1862, Man Ray ha sistematizzato e padroneggiato questa tecnica facendone una firma artistica (cat. 105).

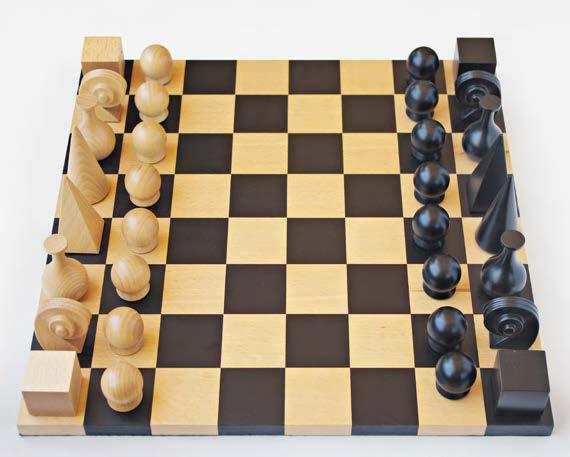

La rottura con Lee Miller, che riparte per New York nel 1934, è molto dolorosa per Man Ray, il quale sublima il suo smarrimento in un’opera monumentale: All’ora dell’osservatorio, gli innamorati. Questa grande tela, dove appaiono le labbra di Lee Miller sospese tra le nuvole, era appesa sopra il suo letto nell’atelier di rue du Val-de-Grâce. Nel corso dei due anni di realizzazione, l’artista interveniva ogni mattina sulla tela. La declinerà in numerose forme e varianti, in particolare su supporto fotografico: autoritratto, modella, nudo, calco, scacchiera (cat. 258)… Oggetto da distruggere testimonia con umorismo questa dolorosa separazione. Nel 1923, Man Ray aveva ideato Oggetto indistruttibile (cat. 235), composto da un metronomo sul cui braccio oscillante era incollata la fotografia di un occhio. Dopo la rottura, modificherà l’occhio sostituendolo con quello di Lee Miller. Ribattezzata Oggetto da distruggere, l’opera è accompagnata da istruzioni precise:

Ritagliare l’occhio dalla fotografia di una persona amata, ma assente, attaccarlo al braccio oscillante del metronomo, regolare la cadenza desiderata, poi colpire l’oggetto con un martello, mirando bene, per distruggerlo.

Un consiglio che verrà preso alla lettera nel 1957 da studenti contestatori che, in occasione di una mostra a Parigi, quell’oggetto lo distruggeranno davvero. In seguito, Man Ray lo reinterpreterà in versioni diverse, restituendogli il titolo originale: Oggetto indistruttibile. S ebbene Man Ray fosse diventato celebre nell’ambiente artistico per le sue fotografie,

Cut out the eye from a photograph of one who has been loved but is seen no more. Attach the eye to the pendulum of a metronome and regulate the weight to suit the tempo desired. Keep going to the limit of endurance. With a hammer well-aimed, try to destroy the whole at a single blow.

This advice was taken literally in 1957 by protesting students at an exhibition in Paris, resulting in the destruction of the object. Man Ray later reinterpreted it in various versions, restoring it to its original title: Indestructible Object.

Although Man Ray had become famous for his photographs in the art world, it wasn’t until 1933, under the title L’Âge de la lumière, that he published a book that, for the first time, made him accessible to the general public. The first and most surprising part of the book is devoted to a series of photographs showing the play of light projected onto familiar or unusual objects. Accompanied by a poem by Paul Éluard, the second part presents female nudes, followed by a series of portraits and a text by Louis Aragon. The final section, dedicated to rayographs, is presented by Tristan Tzara. He ends his poetic text with these words: “These are the projections, surprised in transparency, in the light of tenderness, of objects that dream and speak in their sleep.”

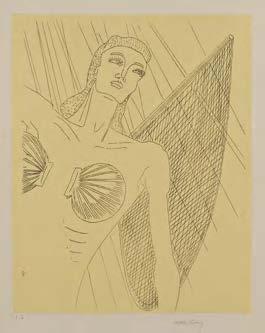

In 1935, Man Ray and Paul Éluard collaborated on Facile, a book combining poetry and photography, laid out by Guy Lévis Mano—typographer, publisher and poet. This collection of five poems by Paul Éluard, who had just married Nusch, became a landmark work of Surrealism. The texts follow the sinuous contours of the female body, magnified by twelve photographs by Man Ray (cat. 124). Two years later, in 1937, Les Mains libres appeared, a collection of over sixty pen-and-ink drawings, accompanied by poems by Éluard. Contrary to traditional practice, it was the poems that illustrated the drawings Man Ray had entrusted to him a few weeks earlier. By overturning the traditional creative scheme, the two artists claimed total artistic freedom (fig. 5).

essenziale. La sua presenza elettrizza il film […], rende reale e concreto il suo personaggio persino in un ambiente surreale” 13 Quella di Kiki è dunque una presenza attiva nella storia di Man Ray, ma è con Lee Miller che lo scambio artistico si fa più complesso14. Miller lascia New York per trasferirsi a Parigi il 10 maggio del 1929. A questa data Man Ray è un artista pienamente affermato nella cerchia dei surrealisti e negli ambienti più avanzati dell’avanguardia parigina, ed è anche uno stimato fotografo di moda15 da quando, nel 1922, Gabrièle Buffet (musicista e consorte di Francis Picabia) lo aveva introdotto al grande stilista Paul Poiret. Da qui la sua carriera nel fashion era decollata: l’artista aveva iniziato a collaborare assiduamente con le maggiori testate del settore (“Vogue Francia”, “Harper’s Bazaar”, “Vanity Fair”, ecc.) e si era imposto come uno tra i più ricercati ritrattisti dell’alta società.

Prima di trasferirsi a Parigi, anche Lee Miller ha alle spalle una certa consuetudine con la fotografia, posando prima per il padre (che da bambina la ritraeva spesso, anche nuda), poi per alcuni dei più rinomati fotografi di moda del tempo. Dal 1927 è infatti una delle modelle simbolo di “Vogue” (è Condé Nast ad averla “scoperta”). Nello stesso anno, il suo volto ritratto dal celebre disegnatore Georges Lepape compare sulla copertina del numero di marzo di “British Vogue”. Anche Edward Steichen, subentrato a Adolf de Meyer nel 1923 come fotografo ufficiale della rivista, la ritrae più volte, contribuendo alla sua ascesa come icona del fashion. Tuttavia, al suo arrivo a Parigi, Miller matura l’idea di passare dall’altra parte dell’obiettivo: “Preferisco fare una foto che essere una foto” è la frase, ormai c elebre, c on cui Miller risponde nel 1932 a una giornalista del “New York World Te -

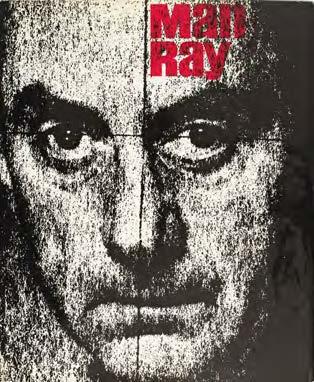

Fig. 3.

Copertina del libro / Cover of the book, Man Ray: Portraits, Éditions Prisma, Paris 1963 Telimage, Paris

13 Mark Braude, Kiki de Montparnasse. Artista, intellettuale, musa fra Modigliani e Man Ray, traduzione di Alessandro Zabini, Superbeat, Vicenza 2022, p. 189.

14 Contributo fondamentale sul rapporto tra Lee Miller e Man Ray è quello di Federica Muzzarelli, Lee Miller/Man Ray. Arte, moda, fotografia, Atlante, Bologna 2016. Per ulteriori approfondimenti su Lee Miller si rimanda a Carolyn Burke, Lee Miller: A Life, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2007. Sulla sua fotografia di moda si veda Becky E. Conekin, Lee Miller in Fashion, Thames and Hudson, Londra 2013.

15 Per contestualizzare il lavoro di Man Ray nel campo della moda si rimanda a Federica Muzzarelli, Moderne icone di moda. La costruzione fotografica del mito, Einaudi, Torino 2013; Claudio Marra, Nelle ombre di un sogno. Storia e idee della fotografia di moda, Bruno Mondadori, Milano 2010; Richard Martin, Fashion and Surrealism, Rizzoli, New York 1987.

and when she had appeared—uncredited—in some of the most radical avant-garde films, including Ballet mécanique by Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy, as well as several of Man Ray’s own. Alongside her indomitable and rebellious character, her literary and artistic talents had not gone unnoticed. Introducing Kiki’s Memoirs7 (fig. 1), Ernest Hemingway perceptively captured the unconventional spirit of her writing: “I think Kiki’s book is one of the best I’ve read since The Enormous Room [by E.E. Cummings]. It might not be translated, but if the translation doesn’t convince you, learn French and read it. […] This is a book written by a woman who was never a lady. For nearly ten years she was on the verge of becoming what today we would call a Queen—which, of course, is very different from being a lady.”8 Hemingway’s appreciation—unusual, given his reluctance to write prefaces—was sincere: in 1931, he gifted a copy of the book to Carlos Guffey, the doctor who had saved the lives of his wife and son9 Upon receiving the unfinished manuscript, Man Ray had instantly recognized its quality, encouraging Kiki to complete it and find a publisher: “The style was direct, rudimentary, but not lacking in sensitivity and insight; an implicit condemnation of provincial stupidity and hypocrisy, of self-interested charity and moralism. […] It wasn’t literature, it was a faithful portrait of Kiki herself, with a terrible yet tender sincerity.”10 In the United States, the book was banned for its supposedly immoral content. The “terrible sincerity” that defined Kiki’s writing also infused her painting style, which was admired by several avant-garde leaders. Among her earliest supporters, alongside Man Ray, were Sergei Eisenstein and Robert Desnos. The latter even penned the preface to the catalog of Kiki’s first solo exhibition, held to notable success—both critical and commercial—at the Galerie “Au Sacre du Printemps” in March 1927 11

Some of Man Ray’s masterpieces—works that left an indelible mark on the history of Surrealism and, more broadly, on 20th-century art—were inspired by his relationship with Kiki de Montparnasse. Among them, Le Violon d’Ingres, which first appeared in 1924 in the pages of Littérature (and was sold at auction in 2022 for the record sum of $ 12.4 million), and the photograph Noire et blanche, published in May 1926 in the French edition of Vogue as Visage de nacre et masque d’ébène. Now considered an iconic Surrealist work, Noire et blanche has been variously interpreted as an exercise in formalist experimentation, as the product of modernism’s drive to universalize and neutralize racial differences or as an example of avant-garde “primitivism”. However, studying the work’s exhibition history reveals that, at the time it was created, Noire et blanche primarily served to cement Man Ray’s reputation within the fashion industry. As explained by Wendy A. Grossman and Steven Manford, its “retroactive placement” among the icons of Surrealism began only after the artist’s death in 1976: “ This highly aestheticized composition, which juxtaposes the ultra-modern woman—Kiki—and the seemingly ‘ultra-primitive mask’, helped establish Man Ray’s reputation as a pioneer in the world of fashion photography.” 12 Viewed from this perspective, Kiki’s role in the creation of the photograph takes on even greater meaning: with her sleek haircut à la garçonne and meticulously gauged makeup, she fully embodies the independent, emancipated figure of the “New Woman”, who was reshaping fashion, style and Western visual culture during those years. Kiki’s contribution also proved decisive—however fleeting her on-screen appearances—in Man Ray’s short films Le Retour à la raison (1923), Emak Bakia (1926) and especially L’Étoile de mer (1928) (fig. 2). As Mark Braude argues, “Kiki’s collaboration was essential. Her presence electrifies the film […] making her character vivid and real, even within a surreal environment” 13 . Kiki was thus an active force in Man Ray’s creative life, but it was with Lee Miller that his artistic relationships grew more complicated14. Miller left New York and moved to Paris on May 10, 1929. By that time, Man Ray was a well-established figure among the Surrealists and in the most progressive circles of the Parisian avant-garde. He was also a respected fashion photographer15, having been introduced to renowned couturier Paul Poiret in 1922

7 The autobiography was published in France in 1929 by publisher Henri Broca, Kiki’s partner at the time, with a preface by Japanese artist Foujita. The edition Kiki Souvenir, with an introduction by Ernest Hemingway, came out the following year.

8 Ernest Hemingway, introduction to Kiki Souvenir, now in Kiki de Montparnasse, Infinitamente prezioso. Ricordi ritrovati, Milan, excelsior 1881, 2007, pp. 15-16.

9 Serge Plantureux, preface to a Kiki de Montparnasse, Infinitamente prezioso, cit., p. 9.

10 Man Ray, Autoritratto (1963), translated from the English by Maura Pizzorno, Milan, Gabriele Mazzotta editore, 1975, p. 133.

11 The gallery, open between 1925 and 1929, was established by Polish-born composer and musicologist Jan Effenberger-Śliwiński. Among the artists who exhibited there works there: Otto Hahn, Mela Muter, Wanda Wolska and André Kertész.

12 Wendy A. Grossman and Steven Manford, “Unmasking Man Ray’s ‘Noire et blanche’”, in American Art, vol. 20, n. 2, 2006, p. 142. On this work, see also Whitney Chadwick, “Fetishizing Fashion/Fetishizing Culture: Man Ray’s ‘Noire et blanche’”, in Oxford Art Journal, vol. 18, n. 2, 1995, pp. 3-17.

13 Mark Braude, Kiki de Montparnasse. Artista, intellettuale, musa fra Modigliani e Man Ray, Vicenza, Superbeat, 2022, p. 189.

14 A key contribution on Lee Miller and Man Ray’s relationship is Federica Muzzarelli, Lee Miller/ Man Ray. Arte, moda, fotografia, Bologna, Atlante, 2016. For further research on Lee Miller, see Carolyn Burke, Lee Miller: A Life, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2007. On her fashion photography see Becky E. Conekin, Lee Miller in Fashion, London, Thames and Hudson, 2013.

15 To contextualize May Ray’s work in the field of fashion, see Federica Muzzarelli, Moderne icone di moda: la costruzione fotografica del mito, Turin, Einaudi, 2013; Claudio Marra, Nelle ombre di un sogno. Storia e idee della fotografia di moda, Milan, Bruno Mondadori, 2010; Richard Martin, Fashion and Surrealism, New York, Rizzoli, 1987.

3. Autoportrait, 1916

“Un’opera in particolare, battezzata Autoritratto, suscitò i commenti più sarcastici. Su uno sfondo di pittura nera e alluminio avevo attaccato due campanelli elettrici e un vero pulsante. Poi avevo semplicemente appoggiato la mano sulla tavolozza e quindi sulla tela, imprimendovi l’impronta a mo’ di firma. Tutti quelli che provarono a premere il bottone rimasero delusi perché il campanello non suonava.

[…] Mi diedero dell’umorista, ma io non avevo alcuna intenzione di fare dello spirito. Mi proponevo semplicemente di stimolare lo spettatore ad assumere un ruolo attivo nella creazione.”*

Alcuni storici considerano questo autoritratto come uno dei primi oggetti dadaisti. È andato perduto o distrutto come molti suoi collage, e dell’opera originale esiste solo una fotografia di 9,5 × 7 cm conservata nelle collezioni del Centre Pompidou. Nel 1963, partendo da questa fotografia, Man Ray ne creò una replica, e nel 1970 una serigrafia su plexiglass.

“One panel particularly, called Selfportrait, was the butt of much joking. On a background of black and aluminium paint I had attached two electric bells and a real push button. In the middle, I had simply put my hand on the palette and transferred the paint imprint as a signature. Everyone who pushed the button was disappointed that the bell did not ring. […] I was called a humorist, but it was far from my intention to be funny. I simply wished the spectator to take an active part in the creation.”* Some art historians consider this selfportrait to be one of the earliest Dada objects. Lost or destroyed, like many of Man Ray’s assemblages, the original work survives only in a 9.5 × 7 cm photograph held in the collections of the Centre Pompidou. Using this photograph, Man Ray created a replica of the assemblage in 1963, followed in 1970 by a screenprint on plexiglass.

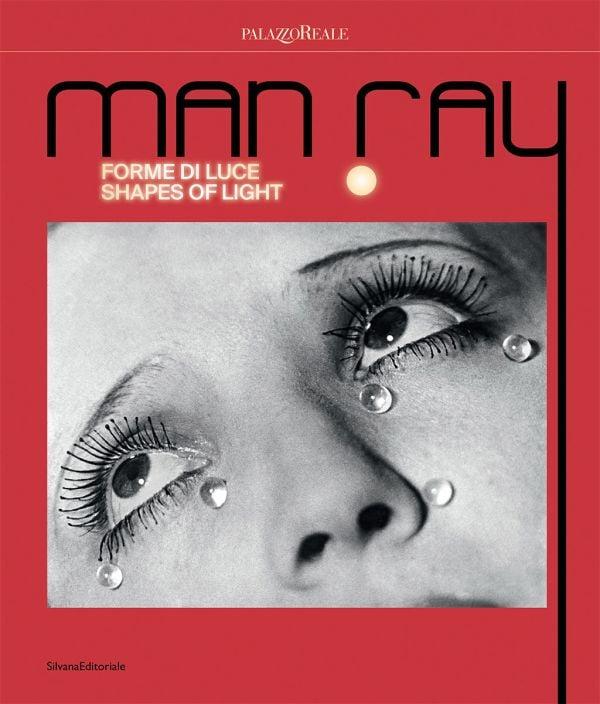

48. Larmes (Glass Tears), 1932 Lacrime o Lacrime di vetro, una delle fotografie più celebri di Man Ray, all’inizio è un semplice scatto pubblicitario per il mascara Cosmecil di Arlette Bernard, e lo si trova nelle riviste dell’epoca con lo slogan: “Piangete al cinema, piangete a teatro, ridete fino alle lacrime, senza timore per i vostri begli occhi…”

Nel 1932, Man Ray fa posare Lydie, modella e ballerina di cancan, e le attacca sul viso delle piccole perle di glicerina. Scatta diverse versioni del volto intero poi, in camera oscura, le ingrandisce, inquadra solo gli occhi della modella e infine isola un unico occhio imperlato di lacrime di vetro.

Tears or Glass Tears, one of Man Ray’s most iconic photographs, was originally conceived as a simple advertisement for Arlette Bernard’s Cosmecil mascara, which appeared in magazines of the time with the slogan: “Cry at the cinema, cry at the theatre, laugh until you cry, without fear for your beautiful eyes…”

In 1932, Man Ray photographed Lydie, a French cancan dancer and model, adding small beads made of glycerine to her face. He took several versions showing her full face. Then, in the darkroom, he enlarged the image and cropped it to focus only on the model’s eyes, eventually isolating a single eye adorned with glass-like tears.

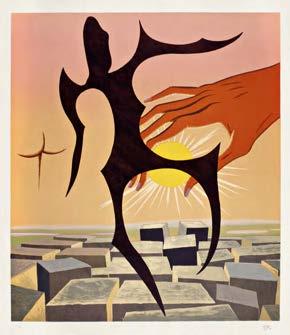

244. Natacha (Ballade des dames hors du temps), 1970

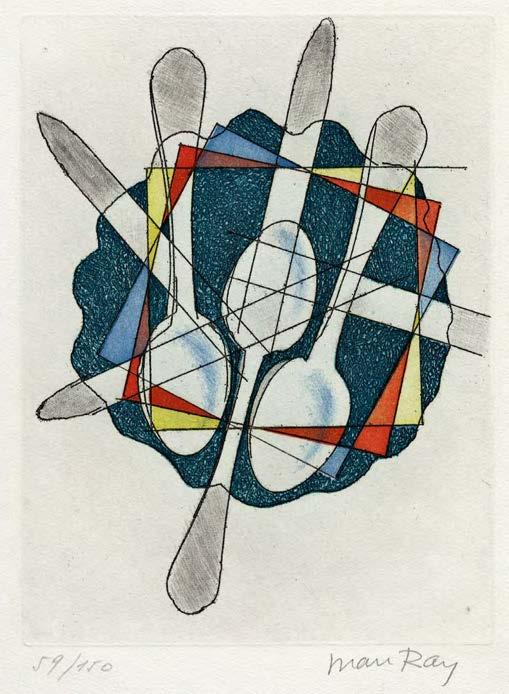

245. Le Rébus, d’après le tableau de 1938, 1971

246. Le Beau Temps, d’après le tableau de 1939, 1973

247. Electromagie (Découvert), 1969

Ce

sont les projections, surprises en transparence, à la lumière de la tendresse, des objets qui rêvent et qui parlent de la tendresse, des objets qui rêvent et qui parlent dans leur sommeil.

Tristan Tzara, Photographies 1920-1934, Éd. Cahiers d’Art, Paris 1934

[Sono le proiezioni, sorprese in trasparenza alla luce della tenerezza, oggetti che sognano e parlano di tenerezza, oggetti che sognano e parlano nel sonno. / These are projections, glimpsed through transparency, in the light of tenderness, objects that dream and speak of tenderness, that dream and talk in their sleep.

Tristan Tzara, Photographies 1920-1934, Éd. Cahiers d’Art]

167. Rayographie, 1921

168. Rayographie, 1922

209.

Connaissant son [de Poiret] intérêt pour toutes les branches des arts, je lui apportai mes photographies de nus. Il les admira beaucoup et dit : dommage que les femmes ne puissent pas porter des vêtements transparents.

Man Ray, Autoportrait, Robert Laffont, Paris 1964

[Conoscevo il suo [di Poiret] interesse per ogni manifestazione artistica, e gli portai i miei nudi. Li ammirò moltissimo dicendo: “È un peccato che le donne non possano indossare abiti trasparenti.” /

Knowing his [Poiret’s] interest in so many arts, I brought my pictures of the nudes; he admired them very much, saying: “A nude is always in fashion, pity the woman cannot wear transparent clothes.”]

In copertina / Cover Larmes (variante cadrage 2 yeux), 1932 (cat. 49)

Silvana Editoriale

Direttore generale / General Director

Michele Pizzi

Direttore editoriale / Editorial Director

Sergio Di Stefano

Art Director

Giacomo Merli

Coordinamento redazionale / Editorial Coordinator

Silvia Perfetti

Progetto grafico / Graphic Design

Annamaria Ardizzi

Redazione / Copy Editing

Sara Clamor

Traduzione / Translation

Contextus, Pavia (Flavia Frauzel, Laura Tasso)

Impaginazione / Layout

Denise Castelnovo

Coordinamento di produzione / Production Coordinator

Antonio Micelli

Segreteria di redazione / Editorial Assistant

Giulia Mercanti

Ufficio iconografico / Photo Editor

Silvia Sala

Ufficio stampa / Press Office

Alessandra Olivari, press@silvanaeditoriale.it

Diritti di riproduzione e traduzione riservati per tutti i paesi

All reproduction and translation rights reserved for all countries

© 2025 Silvana Editoriale S.p.A., Cinisello Balsamo, Milano

© Man Ray 2015 Trust, by SIAE 2025

© Association Marcel Duchamp, by SIAE 2025

© Succession Picasso, by SIAE 2025

© Comité Cocteau, by SIAE 2025

© Fernand Léger, by SIAE 2025

© Harper’s BAZAAR, Hearst Magazine Media, Inc

© The Sunday Times / News Licensing

ISBN 9788836661398

A norma della legge sul diritto d’autore e del codice civile, è vietata la riproduzione, totale o parziale, di questo volume in qualsiasi forma, originale o derivata, e con qualsiasi mezzo a stampa, elettronico, digitale, meccanico per mezzo di fotocopie, microfilm, film o altro, senza il permesso scritto dell’editore.

Under copyright and civil law this book cannot be reproduced, wholly or in part, in any form, original or derived, or by any means: print, electronic, digital, mechanical, including photocopy, microfilm, film or any other medium, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Silvana Editoriale S.p.A. via dei Lavoratori, 78 20092 Cinisello Balsamo, Milano tel. 02 453 951 01

www.silvanaeditoriale.it

Le riproduzioni, la stampa e la rilegatura sono state eseguite in Italia Stampato da / Printed by Grafiche Lang S.r.l., Genova Finito di stampare nel mese di settembre 2025 / Printed in September 2025

Crediti fotografici / Photo credits

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / ADAGP-SIAE, 2025

Images: Telimage, Paris

a eccezione di / except for pp. 72-73, cat. 28-31; p. 183, cat. 200; pp. 198-199, cat. 229-230; p. 211, cat. 250-251; p. 213, cat. 254; p. 223, cat. 269-270