Introduzione

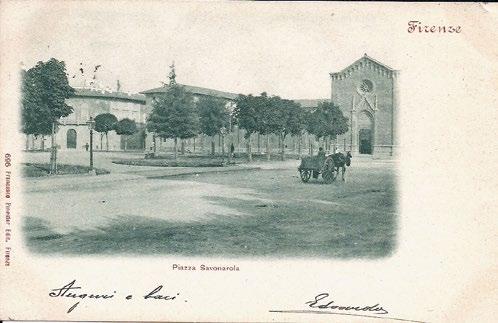

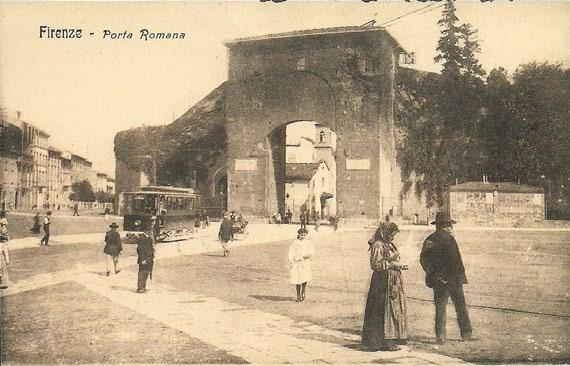

Se dovessimo descrivere la realtà, memori di tutte le metafore contenute nelle officine degli scrittori o dei poeti, useremmo senza alcuna esitazione l’immagine di un labirinto. L’intreccio delle storie che costituiscono la Storia insegna a guardare l’universo come fosse un grande arazzo, un tappeto persiano prezioso, con i suoi disegni cifrati. Ma ciò che non vediamo, sottesa all’universale, è la trama di fili che compongono l’arazzo. L’antica dicotomia tra fabula e intreccio, tanto cara agli studiosi di teoria e critica letteraria, ben si presta a condurci nelle storie della fotografia, della cartolina postale e della cartolina illustrata. Tali oggetti preziosi, che hanno influito sulla vita degli uomini mutandola significativamente nel corso dei secoli, conducono anche a un’altra storia, quella dei Cassettai fiorentini, un antico turno commerciale su area pubblica nato nel 1909 non solo con lo scopo di vendere oggetti turistici ma con la missione di valorizzare il territorio della città di Firenze. Lo testimonia la costituzione di associazioni e consorzi per riaprire i bookshop nei principali musei fiorentini.

Dunque, storie molteplici che si incontrano dando vita a un’unica narrazione umana, sociale, economica. Come afferma Italo Calvino nel Castello dei destini incrociati, è facile confondersi, perdersi nel «pulviscolo delle storie», perché ogni narrazione confluisce nell’altra, spesso senza un nesso logico evidente e, talvolta, misteriosamente. Seguendo queste suggestioni, diventa inevitabile raccontare questo incontro tra la fotografia, la cartolina e il lavoro dei Cassettai, legati da un misterioso fil rouge.

Introduction If we were asked to review all the metaphors that have come from the pens of writers and poets in order to provide a succinct description of reality, we would unhesitatingly adopt the image of the labyrinth. The intertwining of stories that together make up history teaches us to regard the universe as a vast tapestry, a costly Persian carpet, with its ciphered designs. Yet what we do not see is that which underlies the universal, namely the mesh of threads that make up the tapestry. The age-old dichotomy of fabula and plot, so dear to scholars of literary criticism and theory, is well suited to taking us into the histories of photography, the postcard and the picture postcard, phenomena which have had an influence on people’s lives, changing them significantly over the course of the centuries. Tracing their respective developments in fact leads us to another story, namely that of the Cassettai fiorentini, the postcard and souvenir vendors who have been present in the public spaces of Florence since 1909, whose mission has been not only the sale of their wares but also promotion of their city. Indeed, the founding of associations and consortia for the reopening of bookshops in the main Florentine museums attests to their importance.

What we are dealing with, then, are multiple stories that encounter one another, giving rise to a single human, social and economic narration. As Italo Calvino wrote in The Castle of Crossed Destinies, it is easy for us to become confused and lost in the “dust of the tales”, as each narration flows into the next, often without an evident logical connection and sometimes even mysteriously. Taking our cue from these suggestions, we are inevitably drawn to recounting this meeting between photography, the postcard and the work of the Cassettai, which are linked by a subtle fil rouge

Nasce la fotografia

Appellandoci alla tradizione storiografica, notiamo che la fotografia fece la sua prima apparizione ufficiale quando, nel 1839 in Francia, sull’ondata del Positivismo, François Jean Dominique Arago illustrò all’Accademia di Francia l’invenzione della dagherrotopia ad opera di Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre. Un’idea straordinariamente rivoluzionaria che, da quel momento in poi, si diffuse sia in Europa che nei continenti oltreoceano. La fotografia non solo divenne un mezzo di comunicazione innovativo in grado di immortalare istanti, persone, oggetti, paesaggi ed eventi, ma rappresentò anche un nuovo modo di vedere e di raccontare la realtà, al pari delle grandi arti come la pittura o la scultura, fino a venir considerata anch’essa un’arte vera e propria nei secoli successivi. La fotografia ha sempre esercitato un profondo fascino sugli individui, come se essa fosse un oggetto magico in grado di fermare il tempo e con esso ogni sentimento. Sebbene inizialmente fosse considerata con sospetto, fu subito chiaro che si

The birth of photography

Following the historiographic tradition, we note that photography first appeared in France in 1839 in the wake of positivism: François Jean Dominique Arago demonstrated the invention of the daguerreotype – the work of Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre – to the French Academy. This was an extraordinarily revolutionary idea which from that moment spread throughout Europe and across the Atlantic. Photography did not only become an innovative means of communication able to immortalise instants, people, objects, landscapes and events; it also represented a new way of seeing and describing reality, on a par with the great arts, such as painting and sculpture. It would indeed be considered an art in its own right over the next centuries. Photography has always exerted a spell on people, as if it were a magical technique able to stop time and every feeling with it. Although it was at first viewed with suspicion, it soon became clear that this was an invention able to record and

trattava di un mezzo in grado di registrare e restituire le emozioni. Anch’essa dunque si trasformava man mano in uno strumento capace di narrare la Storia, al pari della letteratura e delle altre espressioni artistiche.

E come le altre arti, la fotografia si avvalse di tecniche che col tempo andarono incontro a una rapida evoluzione, ramificandosi da subito in diverse tipologie e uscendo dagli studi fotografici. Grazie a nuove e migliori strumentazioni poté essere praticata en plein air per documentare monumenti, palazzi, piazze, paesaggi, fino a diventare aerea. Quest’ultima ebbe notevole rilevanza, riscuotendo successo in ambito politico e militare. Nel 1858 il fotografo francese Gaspar-Félix Tournachon, conosciuto con il nome di Nadar, scattò la prima fotografia aerea. Qualche tempo prima, nel 1855, il fotografo ebbe l’idea di usare le fotografie aeree per mappare e sorvegliare il territorio, una tendenza che ritroveremo anche successivamente. Tuttavia, furono necessari alcuni anni e molti tentativi per riuscire

recover emotions. Gradually photography as well was transformed into a tool able to narrate history, on the same level as literature and other forms of artistic expression.

And like the other arts, photography made use of techniques which over time would see rapid progress; the discipline immediately branched into various subfields as it moved beyond the walls of photography studios. Thanks to better equipment, it could be practised en plein air to document monuments, historical buildings and city squares and even develop into aerial photography. The importance of this last evolution was soon appreciated, and it was successfully employed for political and military purposes. In 1858, the French photographer Gaspar-Félix Tournachon, known as Nadar, took the first photo from the air. Several years before – in 1855 – Nadar had the idea of using aerial photos to map and monitor a territory, an application that we will see again later. Nonetheless,