DISCUSSION SUR L’ART

GERMANO CELANT, ANTONY GORMLEY,

LORIS

CECCHINI IN CONVERSATION *

Germano Celant: The first question that I would like to start with is a general one because I think it’s essential for a specialized audience, but also a general audience, to discuss general trends—not of contemporary art but a situation that shifts from my generation to those younger than me. The idea is why, at a specific moment in the 1990s, there was a shift from a kind of minimal, reductionist form to a particular way of figuration, story, and representation. Why was there a need, a counter-reaction against a specific moment in history—because it was too abstract, too ephemeral, too material, and a need to go back to the human figure on one part, but your human figure or the context, the environment, the space, the architecture. So this is the first question. The second question—

Antony Gormley: Let’s do them one at a time because otherwise we’ll forget the questions. I think the truth is that Donald Judd’s definition of the “specific object” as an independent work of art that has absolutely no reference to anything but itself is a zero point for me. Growing up as a young artist, there was no question that we saw a logical progression in the evolution of art that led to this minimal, absolute zero point. In the manner of Bruce Nauman walking about in his studio, I wanted to return to first-hand experience, and that meant returning to the body, not as an object, but as the place of experience. How about you?

Loris Cecchini: I think things were different for our generation because in the 1990s we tried to return to the narrativity of the object and the idea of the body, but mediated by an already mediatized experience, in which visual art, cinema, and photography were affected differently. I think we need to tell stories about life and what life is, about what reality is and what virtualization is, about what the fictionalization of perceived reality is. At that time in the ’90s, I remember Baudrillard, for example, when he talked about a form of lost reality as a simulacrum of reality itself, and perhaps about what Antony is saying about the centrality of the work of art raising its head again after the ’90s.

GC: So you think, Antony, that the anchorage of walking in space by Bruce, let’s say—and to relate both elements, body and space—was a need of an anchorage of an identity that grows because—we have to remember that also there was a kind of moment of expressionism, you know, that—

AG : —we don’t want to forget it, do we? I think there was a new spirit in painting and a very predictable reaction to the classical puritanism

* Germano Celant introduces the conversation by citing examples of popular talk shows of the time and intends to pursue and structure the discussion around a question-based format with him as the moderator. The original conversation was held at Art Basel in June 2013.

GERMANO CELANT, ANTONY GORMLEY, LORIS CECCHINI EN CONVERSATION*

Germano Celant : La première question que j’aimerais poser est d’ordre général, car je pense qu’il est essentiel pour un public spécialisé, mais aussi pour un public élargi, de discuter des tendances générales – non pas de l’art contemporain, mais d’une évolution qui passe de ma génération à celles qui suivent. La question est de savoir pourquoi, à un moment précis des années 1990, on est passé d’une forme minimaliste et réductrice à un mode particulier de figuration, narratif et de représentation. Pourquoi y a-t-il eu un besoin, une réaction contraire, à un moment précis de l’histoire – parce que c’était trop abstrait, trop éphémère, trop matériel – et un besoin de revenir à la figure humaine mais votre figure humaine, ou au contexte, à l’environnement, à l’espace, à l’architecture ? C’est donc la première question. La deuxième question…

Antony Gormley : Prenons-les une par une. Sinon, nous allons en oublier. Je pense que la vérité, c’est que la définition de Donald Judd de l’« objet spécifique », comme œuvre d’art indépendante qui ne faisait référence à rien d’autre qu’à elle-même, constitue, d’une certaine manière, un point zéro pour moi. Lorsque j’étais un jeune artiste, il était évident que nous assistions à une progression logique dans l’évolution de l’art qui menait à ce point zéro minimal et absolu. À la manière de Bruce Nauman déambulant dans son atelier, je voulais revenir à une expérience de première main, et cela signifiait revenir au corps, pas en tant qu’objet, mais en tant que lieu d’expérience. Et vous ?

Loris Cecchini : Je pense que les choses ont été différentes pour notre génération parce que, pendant les années 1990, nous avons essayé de revenir à la narrativité de l’objet et à l’idée du corps, mais par le biais d’une expérience déjà médiatisée, dans laquelle l’art visuel, le cinéma et la photographie ont été affectés différemment. Je pense que nous avons besoin de raconter des histoires sur la vie et sur ce qu’est la vie, sur ce qu’est la réalité et sur ce qu’est la virtualisation, sur ce qu’est la fictionnalisation de la réalité perçue. À cette époque, je me souviens de Baudrillard, par exemple, qui parlait d’une forme de réalité perdue en tant que simulacre de la réalité elle-même, et peut-être de ce qu’Antony dit à propos de la centralité de l’œuvre d’art, qui a refait surface après les années 1990.

GC : Donc tu penses, Antony, que l’ancrage de la marche dans l’espace par Bruce, disons – la mise en relation des deux éléments, le corps et l’espace –, était un besoin d’ancrage d’une identité qui s’est développé parce que nous devons nous rappeler qu’il y a eu aussi une sorte de moment d’expressionnisme, vous savez, qui…

* Germano Celant introduit la conversation en citant des exemples de talk-shows populaires de l’époque et a l’intention de poursuivre et structurer la discussion autour d’un format basé sur des questions, lui-même en étant le modérateur. Cette conversation a eu lieu à Art Basel, au mois de juin 2013.

[pp. 38–39]

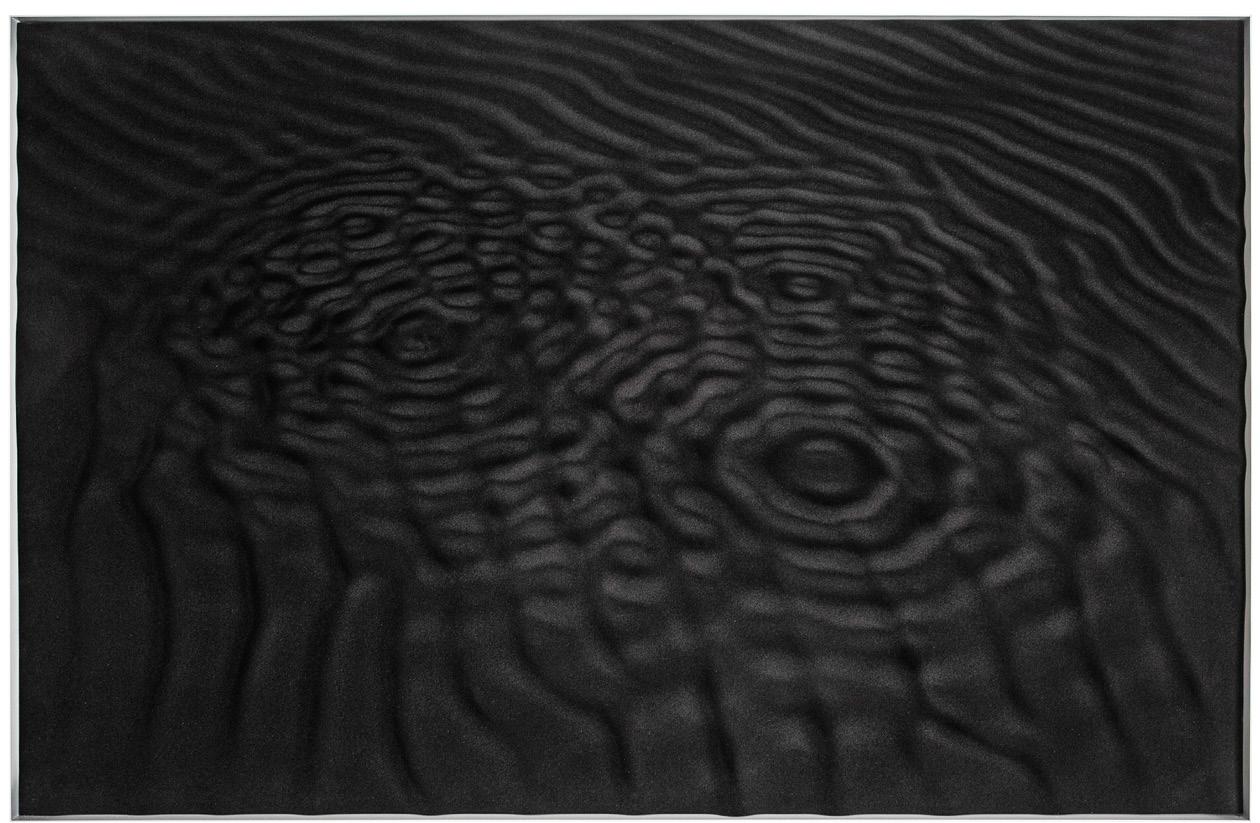

AEOLIAN LANDFORMS (AQUABAT), 2022 cast polyester resin, acrylic resin, nylon fiber, aluminum frame, 180 × 250 × 6 cm Private collection, Florence

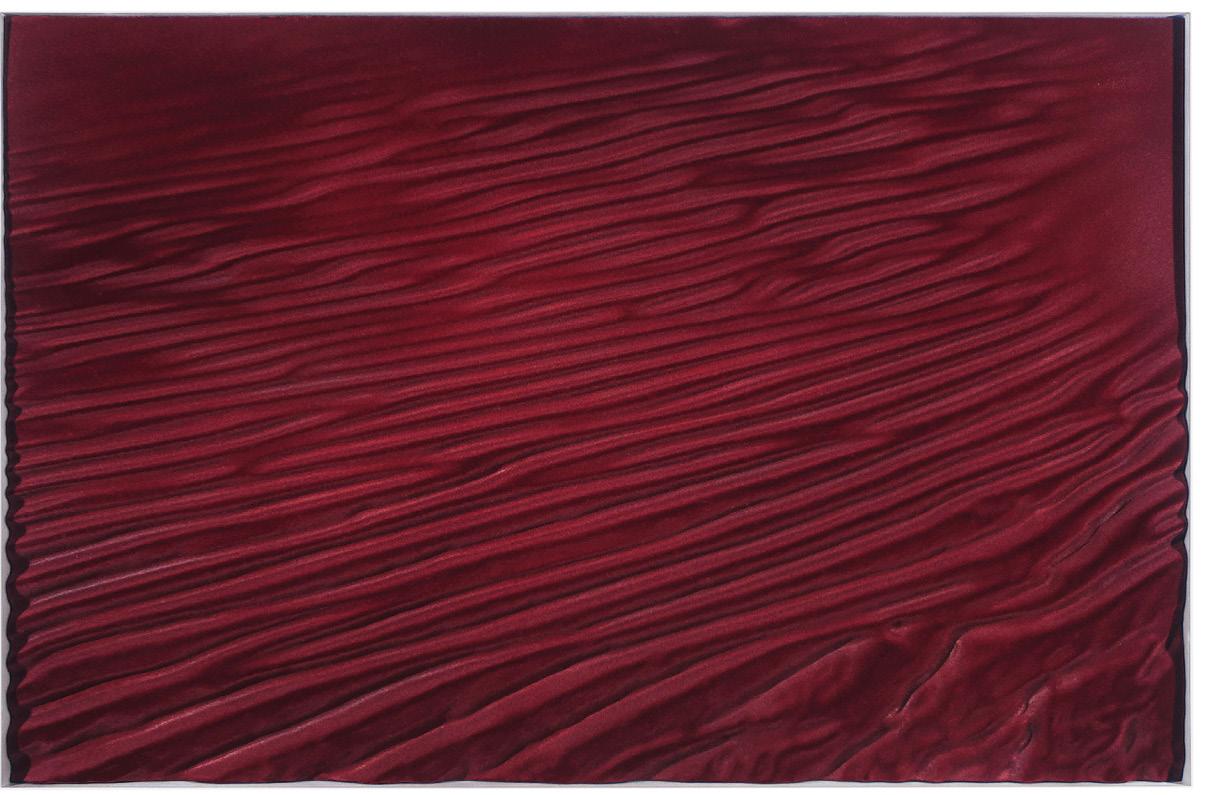

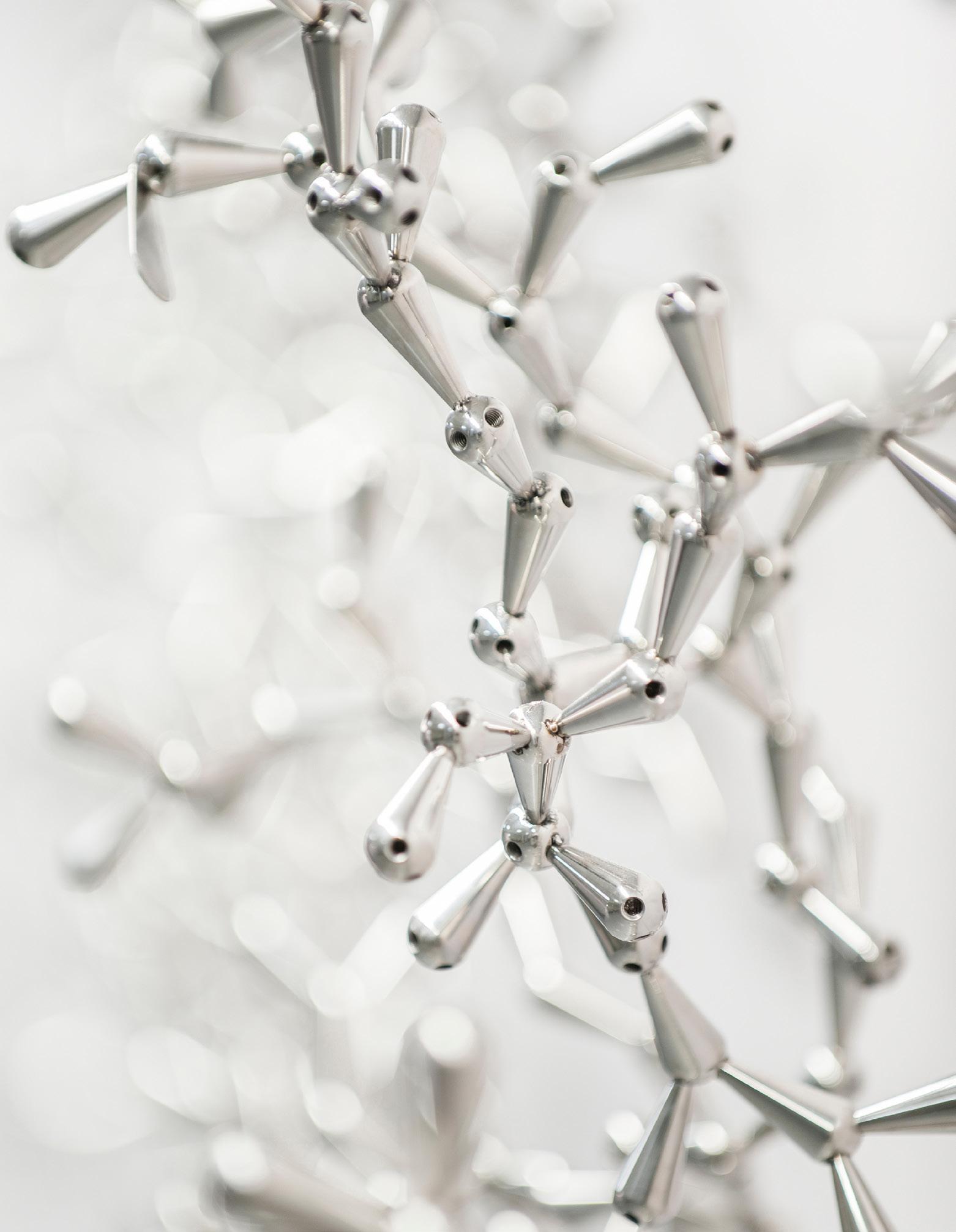

μ GRAPH RELIEFS (SOUR CHERRY 7645C), 2019 polyurethane, epoxy resin, nylon fiber, aluminum frame, 100 × 150 × 6 cm Private collection, Milan

AEOLIAN LANDFORMS (NAMAK), 2024

cast polyester resin, acrylic resin, nylon fiber, aluminum frame, 150 × 200 × 6 cm

Installation view XV Quadriennale d’arte di Roma, Rome, Italy

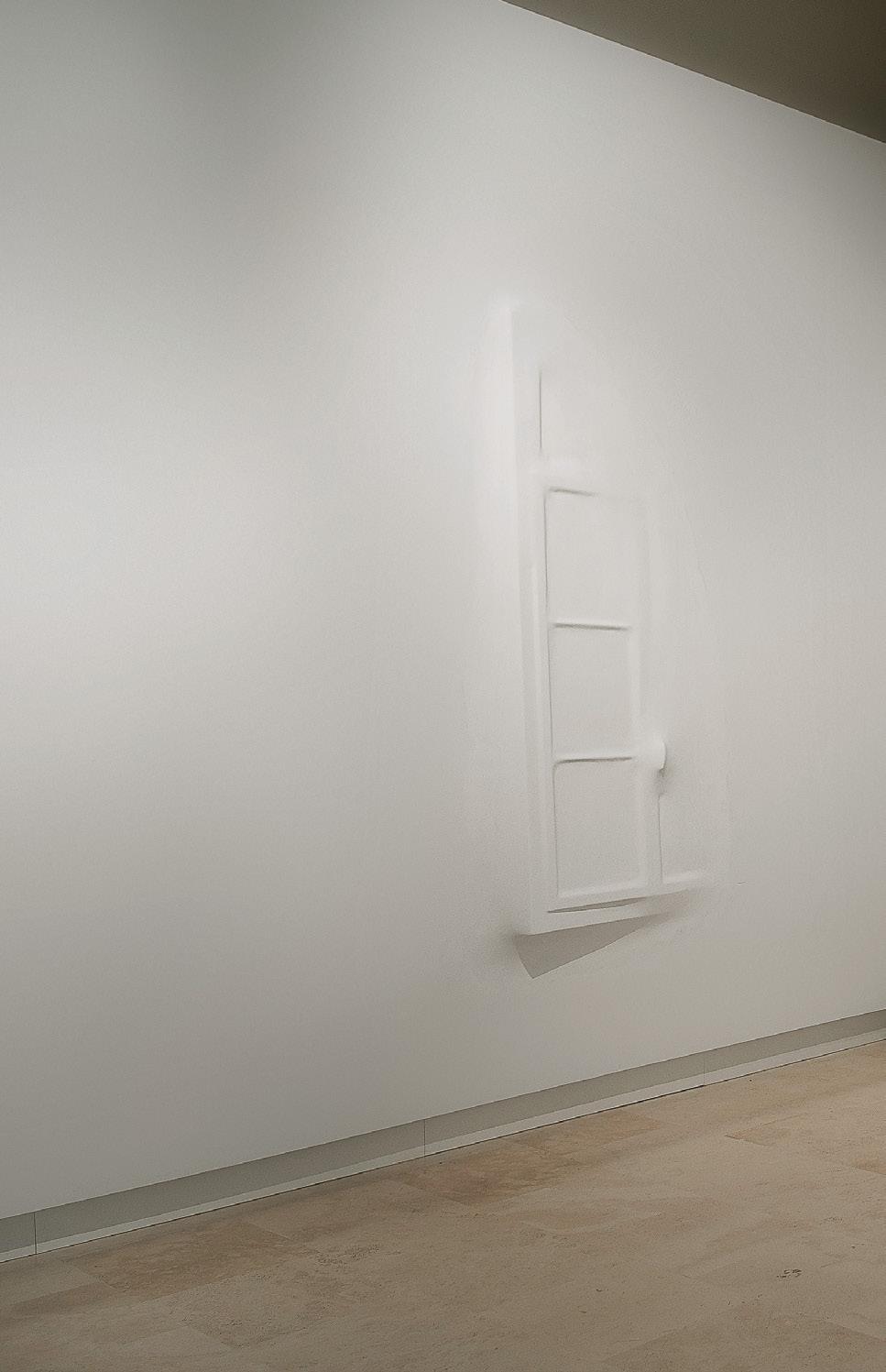

MONOLOGUE PATTERNS (MODEL), 2002–2009

polystyrene, wood, 3M lenticular film, artificial plants, PVC, debris, 160 × 70 × 70 cm Centro per l’arte contemporanea Luigi Pecci, Prato, Italy

RADIANCES (CANADIAN YELLOW SELENITE WITH CONVOLUTION REVERB), 2011 print on Hahnemühle cotton paper, polyurethane resin, PETG, 3M lenticular film, cable ties in polyethylene, transparent thermoformed PET box on galvanized sheet, 112 × 112 × 25 cm

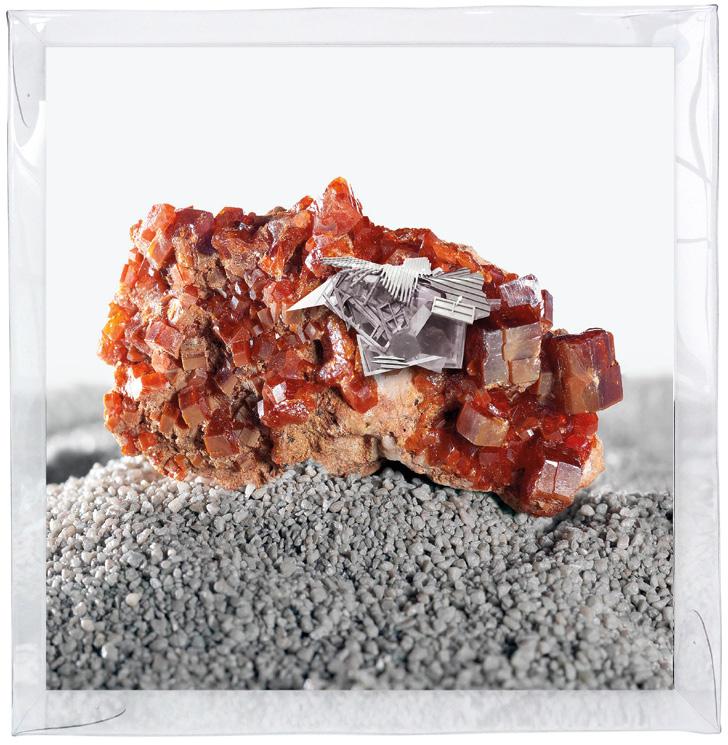

RADIANCES (THOUGHTS OSCILLATORS ON VANADINITE), 2011 print on Hahnemühle cotton paper, polyurethane resin, PETG, 3M lenticular film, cable ties in polyethylene, transparent thermoformed PET box on galvanized sheet, 114 × 114 × 25 cm

RADIANCES (INDIAN CAVAUSITE AND FRACTALIZED VOLUME), 2011 print on Hahnemühle cotton paper, polyurethane resin, PETG, 3M lenticular film, cable ties in polyethylene, transparent thermoformed PET box on galvanized sheet, 114 × 114 × 25 cm

RADIANCES (SOUND PRESSURE AROUND CHINESE VIOLET FLUORITE), 2011 print on Hahnemühle cotton paper, polyurethane resin, PETG, 3M lenticular film, cable ties in polyethylene, transparent thermoformed PET box on galvanized sheet, 114 × 114 × 25 cm

STAGE EVIDENCE (TECHNOBIKE), 2007 urethane rubber, polyethylene, PVC, metal, 160 × 110 cm

UNDECIDED