Any traveller in Libya will benefit from knowing something about the early settlers of this land and the various influences they had on it.

Archaeological research has revealed evidence of Palaeolithic (Early Stone Age) man in Libya. Exhibits in the Tripoli Museum include prehistoric remains demonstrating a progression of techniques from the Old to the New Stone Age. In southern Libya Stone Age rock paintings survive depicting the large game and small animals that were prevalent at the time.

The life of the early Libyans was similar to that of other primitive people. They hunted the animals of the desert, ate their meat, clothed themselves with skins and collected plants and berries. Arrows and stone knives have been found from the second period of the Stone Age.

In later years the Libyans started both to weave cloth and to breed domestic animals. Some Libyans continued their nomadic lifestyle, while others settled down in particular areas of the country. Around the Jebel Nafusa they built houses that consisted of holes five to six metres deep with several rooms excavated at the bottom and a sloping corridor leading down to them from the surface.

Caves were used as dwellings around the Jebel Akhdar area, and on the fertile plains houses were built from a mixture of earth and stones with roofs of palm fronds or branches used from other trees. In the desert the Libyans preferred to live in tents of skin or huts from branches of trees tied together with rope.

Herodotus, the Greek historian who lived in the fifth century b

Opposite: part of the amphitheatre at Sabratha

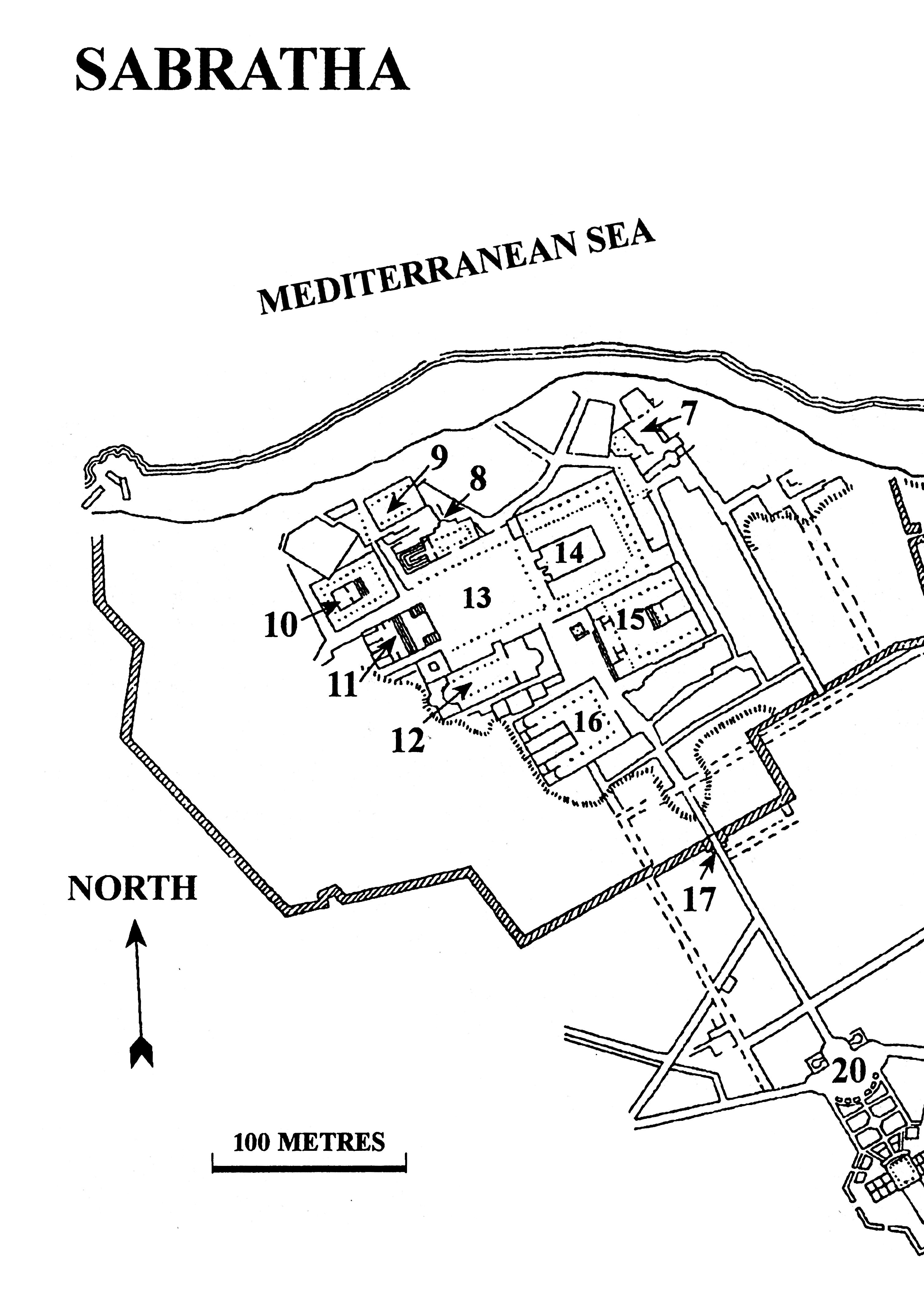

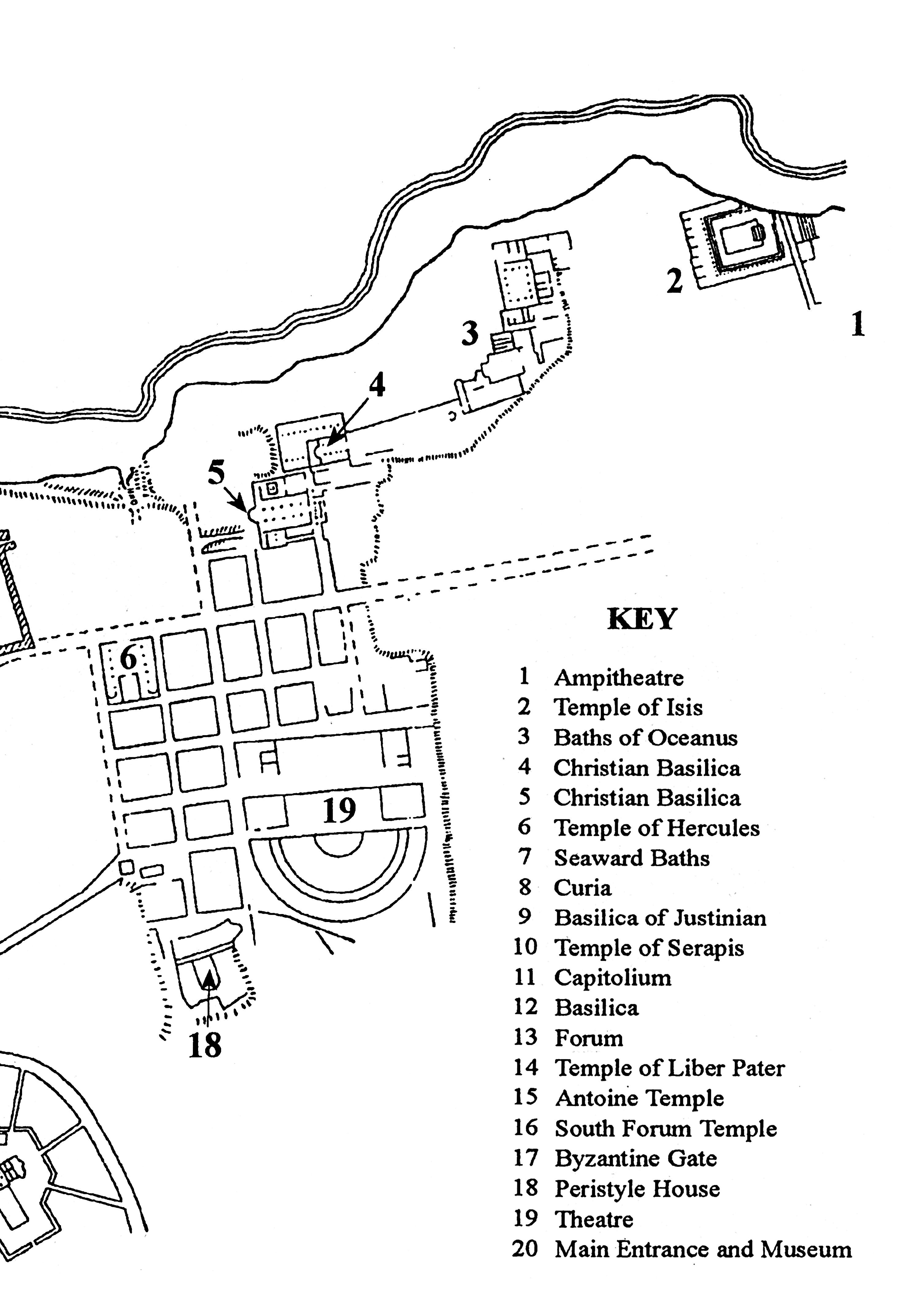

The ancient city of Sabratha is one of the most important histori c a l s i t e s i n L i b y a , a n d s h o u l d n o t b e m i s s e d . I t s t a n d s approximately 67 km from Tripoli, beyond the towns of Janzur (15 km) and Zawiyah (44 km), just off the main road that goes to and from Tunisia, so if time is limited it could be included as a stop off en route. However, there is a considerable amount to see, so it is best done by taking a full day’s trip from Tripoli.

There was an early Phoenician settlement in Sabratha which was later turned into a Roman city towards the end of the first century bc. The Forum, with its temples to the oriental gods Liber Pater and Serapis, contained some of the early buildings. In the second half of the second century ad, a new urban district developed beside the sea to the east of the existing city. This area was laid out via a rectangular plan from the sea front to the theatre, with an important road crossing the district at right angles. A local sandstone was used, but it was so friable that stucco was needed to protect it from erosion, and to take the finer carving and painted details. Stone and marble were imported for fancier effects, or for refacing buildings when money permitted.

Sabratha became a prosperous town during the third century ad and was well known for its ivory and ostrich trade. Ivory was brought from Central Africa via Ghadames and the Fezzan, and ostrich eggs and feathers were highly sought after in Tripolitania. In ad 455 the Vandals conquered Sabratha and left it in decay. The Byzantines then took over until the Arab invasion when the town was used as a military post. In the early twentieth century, under Italian rule, parts of the old town were excavated. The most famous monument to be restored was the Roman Theatre.

It takes about an hour to travel from Tripoli to Sabratha. There is a small kiosk at the entrance selling books and postcards. The

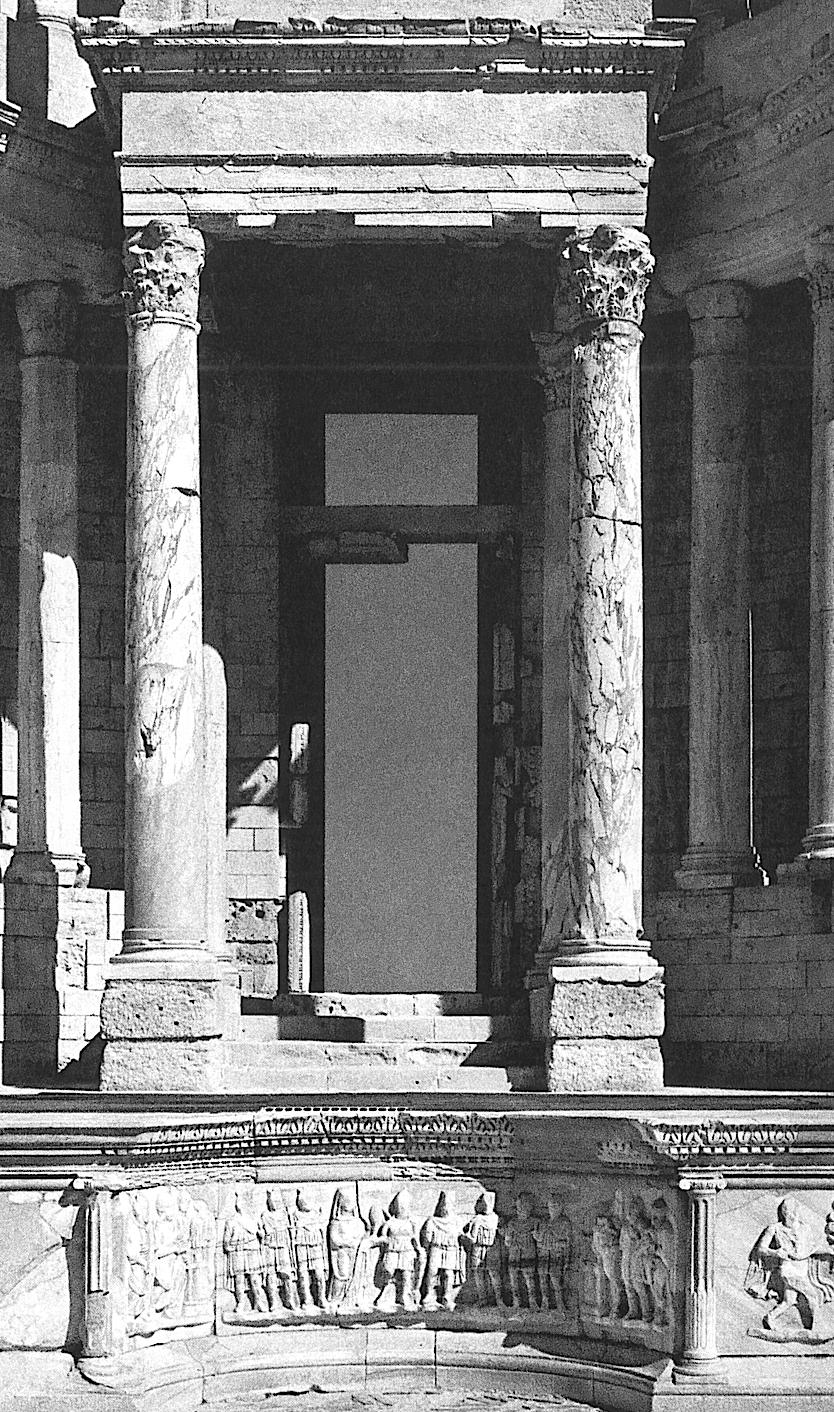

Opposite: Part of the restored scæna of the theatre at Sabratha

Leptis Magna is the most impressive ancient city in Libya and one o f t h e g r e a t e s t c l a s s i c a l s i t e s i n N o r t h A f r i c a . I t s c h e q u e r e d history and its evocative ruins are sure to leave a strong impression on any visitor. If time is very short it is possible to see the ruins on a day trip from Tripoli. It would be far better, however, to take your time and spend a couple of days getting to know the ancient streets and buildings. There are, in addition, several interesting towns to explore en route from Tripoli to Leptis, and beyond Leptis to the east.

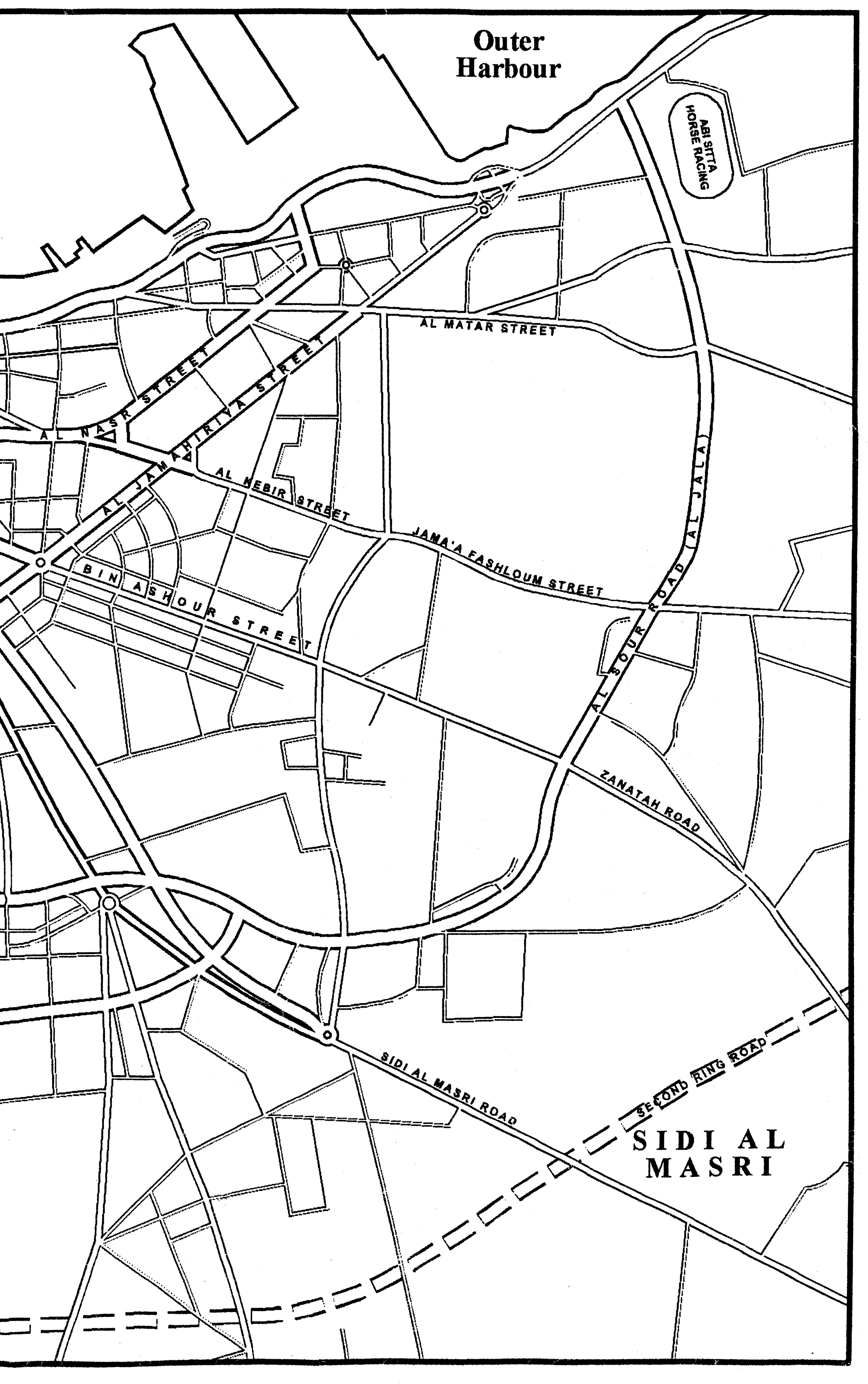

The journey from Tripoli to Leptis Magna will take you east along the coast road to Tajura. This used to be a market centre where villagers met once a week from the surrounding countryside to sell their produce and buy food and clothing. Nowadays it is fast becoming an extended Tripoli suburb, with expensive villas and modern facilities.

The most important building in Tajura is the Mosque of Murad Agha, who was the first Turkish governor of Tripoli in 1551. It looks very plain from the outside, but inside, the large arcaded prayer hall is supported by 48 granite columns which were said to have been brought from the ruins of Leptis Magna.

Travelling on towards the town of Khoms you come to a very charming little hotel called Hotel Nagazza (tel. 0031-626691/92).

Approximately 18 km west of Khoms there is a left turning leaving the main highway and going into the wooded hills. The main building has six bedrooms and two suites, one of which even has a jacuzzi. There is a comfortable lounge, a small dining room and a terrace overlooking the garden. Just down the road there are eleven chalets, which are not as stylish. This is a beautiful place to stay,

Opposite: Triumphal archway at Leptis Magna

In order to travel to the area known as the Fezzan it is best to begin your journey from Sirte. It is a lonely road down to Sabha, so take plenty of water, food and anything else you need to feel comfortable.

Fighting in the Fezzan was not as intense as in other parts of Libya, but visitors should ensure that they have up to date information about conditions before they set out.

For the first two hours you pass through the flat lands of Serir which are covered by stones of all shapes, among which an occasional desert plant grows. Then you begin to see rocky hills and soft sand dunes. These rocks, which have been eroded by harsh winds and burning sun, a variation of temperature and occasional rain, are strange and have curious shapes. They are known as khashem (nose, pointed stone), ras (sharphead), ghelb (heart) and ghara (bastion). The scenery becomes quite dramatic before entering the town of Hun.

Under the Italian regime Hun became the administrative centre of the so-called Military Territory of the South. One facility was a landing ground for aircraft which was the target of numerous raids by the Allies during the war. In 1929 groups of men, women and children were captured and put inside the Turkish fort at Hun to stop them from fighting. Later they were taken to Buwayrat al Hasun and Misurata.

The old medina in Hun is uninhabited, but it is possible to see one of the houses which is more than 100 years old. Each house

Opposite: Cooking a roadside meal, Fezzan

was divided into three units for the extended family – grandfather, father and sons. The houses were built of stone and mud with a roof made from palm trees, and were cool in summer and warm in winter. Each unit had three sets of stairs – stairs from the kitchen to take food up, one for family use, and one for visitors. There was a courtyard where the family could sit outside in the evening. Each unit had a family room, a bedroom and a children’s r o o m . T h

eleven in the morning. There was a store room for dates which, when covered over with sand, would keep for a whole year.

No water was to be allowed near the toilet area. Sand was used daily and from time to time the farmers would take the excreta to use on the farms as manure. The shelf in the kitchen would be made from palm wood. There was a cat flap under the door and the main door would be made from a palm tree with an intricate pattern painted in oils.

The Thakirat Al Medina (Memory of the City) Museum is on the main street, close to the post office and near the turning for the old medina. It displays baskets and claypots, a flour grinder and a bird trap, among other exhibits. There is also a collection of dolls depicting the seven days of a wedding, a 600 year old

piece of palm tree and a 700 year old flour grinder from the first village at Hun. Close to the old medina is the charming Jama al Attiqu mosque built around 1870 and rebuilt between 1936 and 1939.

Hun is a good place to stay. There is the Alrawasi Hotel (tel. 091 2146206), which is a five-minute drive from downtown Hun. It has airconditioning, room service, buffet restaurant and free wi-fi, as well as shops in the hotel.

From Hun, another lonely road takes you to Sabha, the capital of the Fezzan. The town is modern with well-stocked shops, but part of the old town also remains intact.

One interesting site in the town is the ‘Elkilla’ castle, an old Ottoman fort built by the Turks for defensive purposes. It stands on the only hill in Sabha next to the airport. The base is used by the military so you cannot go inside and you should be careful if you want to take photographs. A picture of this castle is printed on the back of every 10 dinar note.

Mu’Ammar Gaddafi spent part of his childhood there. His parents moved from Sirte to Sabha to try to find more fertile land and Gaddafi continued his education at the ‘Point of Light’ school just around the corner from the Al Kaala Hotel.

Until recently, his bedroom was carefully preserved with a few personal belongings in the middle of the Leader’s Roundabout – the Jazeerat al Kaied.

There are an increasing number of hotels in Sabha. There is the Byt Sabha Hotel on the Oubar road on the edge of town near the airport. It is clean and modern. Tel. 0712637300. Another good hotel is the Al Kaala in the centre of town along Jamal Abdul Nasser St. There is another hotel further along the same street called the Al Fatah Hotel, P.O. Box 787 (tel. 071-623106/627670).

A few years ago it was a pleasant place to stay, but now it is unfortunately rather run-down. It is perhaps still worth climbing the nine flights of stairs to photograph the attractively laid-out city and the surrounding hills.

Al Khalij is the area along the coast stretching from Wadi Zam Zam to Zuetina, with the town of Agidabia as the centre of the province. There are many small villages and towns dotted along the way so that you can stop for petrol, groceries, or refreshm e n t

.

archæological sites to be visited.

Sultan was referred to by Arab geographers, and travellers such as the eleventh-century Ibn Hawqal, as being a city with strong walls supported by castles and forts. There were many goats, and ships frequently visited the port. The Arab geographer Al Badri also referred to the town as having a mosque, baths and markets.

Since 1962 the Libyan Department of Antiquities has partially excavated the important Fatimid site revealing the market, gates, mosque and forts. As you reach the small modern village from Sirte, you will see a pair of green iron gates on the northern side of the road. There is a small admission fee to the site which includes a museum with a collection of early Islamic pottery. You can also see the huge bronze statues of the Philæni brothers, taken from the Italian marble arch, which was built in the 1930s and demolished in 1973.

It is said that when the rival cities of Carthage and Cyrene wanted to establish an agreed frontier, it was decided to solve the problem by giving the responsibility to athletes rather than to diplomats. Two pairs of runners, one Carthaginian and one

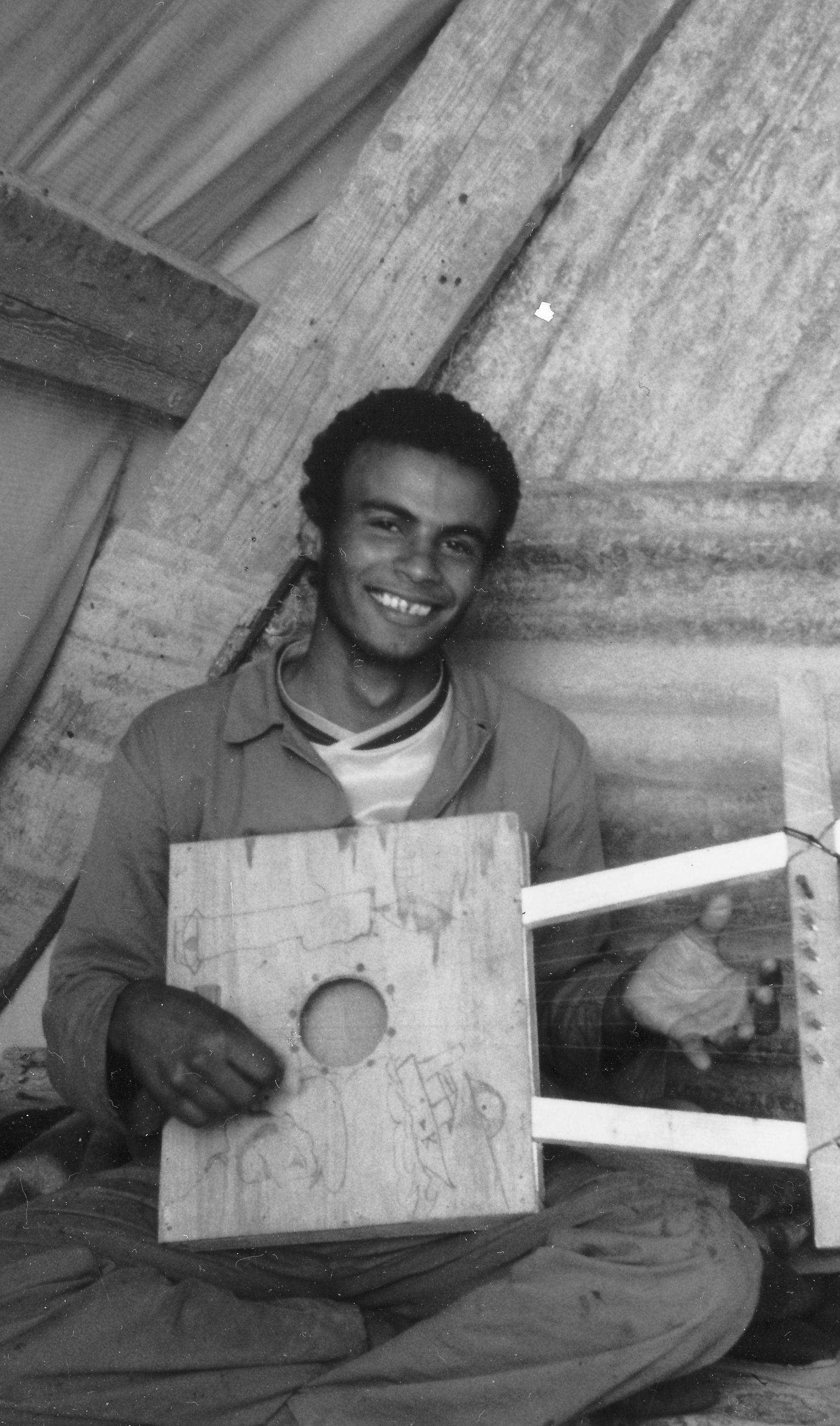

Opposite: A musician in his tent at Boreum

Cyrenean, set out simultaneously, one from Carthage and one from Cyrene. It was agreed that wherever they met, the boundary would be established. However, when the pairs of athletes met it was close to the foot of the Gulf of Sirte, which suggested that the Carthaginians had started sooner and had therefore cheated. The Cyreneans said that they would only be prepared to accept the boundary if the two Carthaginian athletes, the Philæni brothers, were willing to be buried alive at the place they h a d r e a c h e d . T

internment on behalf of their country. They were buried alive beneath the sand and the ‘Altars of the Philæni’ were erected to commemorate their sacrifice.

The marble arch was erected after the junction of the road leading to the village of Nofilia and close to the Wadi Matratin. The construction was built to mark the completion of the coastal road and was visited by Mussolini and the King of Italy. The Arch was at one time a well-known landmark and thousands of men passed through it when travelling east or west.

Travelling along the coast you come to the small town of Bin Jawwad followed by the oil town of Ras Lanuf. The next village you come to is Al Agaylah, and about 9 km west of there is the small promontory of Bu Sceefa which is close to the island or reef of Bu Sceefa two kilometres offshore. There are the remains of a small Roman fort on the promontory itself, probably that of Automalax.

Communications were more easily maintained by sea than by land, so the garrison was employed as a small coastguard detachm

t . T

surrounding walls on the landward side. The buildings within the perimeter wall consisted of small rectangular rooms but a larger building, possibly a castle, stood close to the sea at the northern end of the site, surrounded by a shallow ditch.

Today, there is little left of the settlement, and although you can still see the outline of some of the buildings, a high dune obscures most of the inner parts of the castle. Fragments of pottery are still scattered over the site, some local handmade ware, some ‘ribbed pottery’ from the later Roman period, and small pieces of green-glazed Byzantine pieces.

Site plan of Automalax

To get to Bu Sceefa you have to take a four-wheel-drive vehicle or walk several kilometres from the main road to the sea. There is a small community of fishermen living next to the site who will make you welcome.

C o n t i n u i n g e a s t w a r d o n t h e

small village of Agaylah. There are the remains of an Italian fort

Sugarloaf-shaped wind chimneys on the roof of the mosque, Awjilah

Climb onto the roof and you will get a good view of the old town and the surrounding area. Close by is the little Al Suru castle. It has a rectangular shape with an arch at the entrance. It is 40 square metr es with a n u mb er of s mall r oo ms inclu ding th e g u ar d s ’ rooms.

Unfortunately, the whole area has problems with sand movement,

but in spite of the environment the old mosque and castle have stayed in very good shape.

If you wish to visit Awjilah you need to stay overnight at the modern village of Jalu nearby. The Jalu Hotel (tel. 064 7304030) is situated along the main street. The hotel is rather basic but each bedroom has satellite TV. You will need to take your own sheets