BANDEROLE TO KARI STEIHAUG

Monica Aasprong

“hope never asked for a home only a tinted heft a dirty flick of the cloak”

Experience

To entreat the thing. The physicality of it. To hold back. Not to accept the passing of time, impermanence. This is understandable. It is akin to writing. To hold back. Not let go, not yet, not quite yet, and not completely. To fasten. To find the words to fasten them with, the experiences, or else it is new experiences we seek, in the language, to weave the new linguistic experiences together with some old experiences. Can the one who reads also discover a completely new experience? Not in a psychological, or historical sense, but perhaps through becoming familiar with a different side of the language. To watch it fracture, or stretch differently than it normally does, and that this movement in the plasticity of the language, and actually in the matter, may evoke a feeling one has not felt before.

— Casper André Lugg, de minste bærer vann (2022)

Thread Spool Rewind Wool

I hang out with these words, I fraternise with them, hold them in the hand, write them down with my hand, try to see if the sound of them, or the sight of them, can divulge a secret. That it cannot be accidental, that they have been given precisely the name they have got. One can study semantics, etymology, the meanings, and ambiguities, but I am no linguist, not very interested actually, in linguistics; I am however very interested in dictionaries, not so much in all the explanations they can offer, the connections and insights, but more as a material storage unit, that it is stored there somehow, the material of language, as though it were kept in a bank vault, or seed vault. I see these words that are stored there, one below the next, one after another, enrolled in the census, one might say, in alphabetical order, or by theme, or ancestry, or genealogy, for they surely have a genealogy, they bear a kinship to each other, they have evolved through time, and can never be locked into any final form.

21

28

The winter rose from the series To clean out a home ( 2021–22 ). Hand tufting, 120 × 80 cm

29

After the market (2009). Installation: Unravelled wool garments, knitted image after the painting The Gleaners (1857), Jean-Francois Millet. The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo

After the market (2009). Installation: Unravelled wool garments, knitted image after the painting The Gleaners (1857), Jean-Francois Millet. The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo

TH E THREADS IN A WOR K OF LOV E

Kjetil Røed

“For when one says, that love is recognisable through its fruits, then one likewise says, that in a certain sense love itself is invisible, and precisely therefore can only be recognised through its revealing fruits. […] every life, also that of love, is invisible as such, yet is revealed in another. The life of a plant is invisible, the fruit its revelation; the life of thought is invisible, the expression of speech its revealing feature.”

— Søren Kierkegaard, Works of Love (1847)

We lack language for the interstices in the public sphere for everything that exists between what is and what is not. We either think or we don’t think. We either love or we don’t love. We are either politically active, or we are not. We either make art or we don’t. It’s as if we in the mainstream culture are not capable of articulating and acknowledging what is really important; all the stages from A to Z, those ambiguous grey zones, which our lives in fact consist of. Love, friendship, solidarity, a direction in life are all life events that continuously begin anew, circle back, and never end up with an unequivocal outcome that we can come to terms with. Perhaps it’s because the time we live in, which would prefer to have a clear answer, does not have the patience to cultivate a more subtle notion of what is important for us.

The fruits of love

Take love. We can of course speak of the unconditional love between parents and children, or between partners, or friends, but it is the daily practice that is the spawning ground for love’s existence, and not forms that will lock it into a concrete condition or idea. If the principles and imperatives are allowed to define the conditions—“you are my one and only”, “I would sacrifice my life for you”— life together would become entrapped in absolutes, which can overshadow the small incidences in daily life that nourish, differentiate and foster love.

The French author Georges Perec suggests that it is within the network of all these quotidian practises that we find the origins of something new; it is here we find insight and productive approaches to change. He

107

128

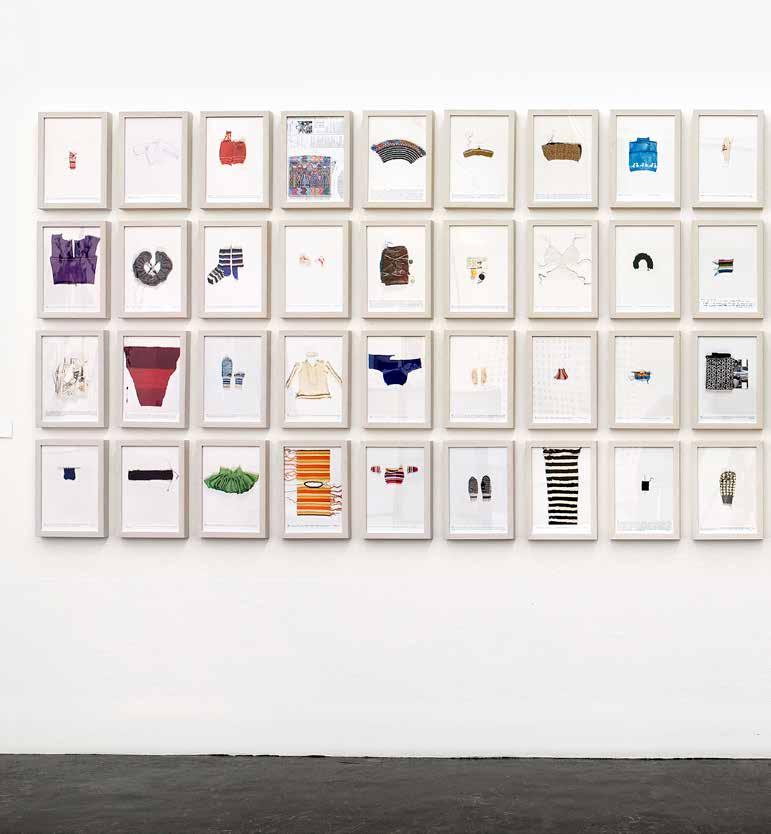

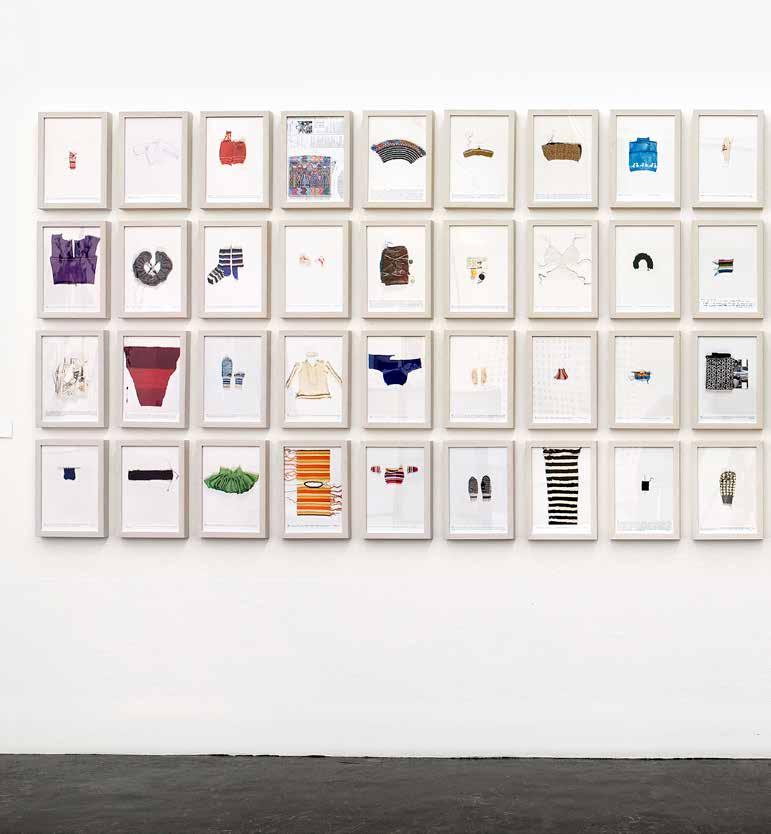

Archive: The unfinished ones . In progress

ARCHIVE: TH E UNFINISH ED ONES

(1998 –2018) 195 photos with text in A4-format

An unfinished knitting project is not anything you want to display; it is often placed in a bag at the back of the closet. At the same time it is invested with personal involvement and is often kept from generation to generation. A knitted garment can encompass everything from daily events to great dramas. It is as though a personal handwriting is embedded in the yarn. Since it didn’t become a wool cap, a warm sock or a child’s mitten, thus gaining the role in someone’s everyday life that it was intended for, it became something else. The knitted object became the carrier, or the vessel, of time and thoughts, sorrows and joys, hope and dreams.

When I saw my own unfinished knitting projects again, I remembered something that I thought I had forgotten. The stories were embedded in small beginnings and unfinished garments, and the memories sat in my body. I remembered the pleasure and expectation when beginning something new, the thought of how fine I would look in it, I remember the beau who didn’t last long enough to receive the patterned sweater I was knitting for him, and everything that changed direction along the way.

The unfinished knitted garments have been donated to the archive by acquaintances and strangers, by friends and family, through exhibitions, lectures, radio announcements, and collaborations with school classes. Some knitted garments arrived anonymously in my mailbox, others were left at an exhibition with their story written on a piece of paper.

Archive: The unfinihed ones is a collection and documentary project about unfinished knitted garments and the stories behind them. It is about the poetry in imperfection, the passing of time, and about directing attention to something failed and lost. Most of all it is about love, for another human being, for the act of creating, and for the simple impulse of wanting.

129

Archive: The unfinished ones (1998–2018). Photo and text, 195 pc. A4. National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo. The picture shows a selection of a total of 195 knitted articles

130

131

surrounds us in everyday life.

is contagious; she allows us to see with fresh eyes what

view of what is often considered worthless in our culture

so that we remember things we had forgotten. Steihaug’s

the galloping consumer culture of our time.

ing imperfection, the works become a counterbalance to

archives and arranges them in new contexts. By embrac

associations and memories. They cause time to open up,

ate a room that we can immerse ourselves in, they evoke

them up, or fetches them out of oblivion, stores them in

or fragments of glass found on the beach. She picks

tains, discarded woollen blankets, unfinished knitwear,

life or a desire to keep someone warm. The works cre

about a belief in new beginnings, an abrupt change in

about love, loss, and passion. Perhaps it says something

material carries a multitude of stories about lived life:

works with are worn out woollen garments, faded cur

brought into the light. Among the materials Steihaug

jects, objects that are worn or frayed are all solicitously

role. The things that have been set aside, unfinished pro

expanded significance. It becomes clear to us that this

tions. In her works, found materials gain new value and

or writes with the thread allowing it to coil in new direc

tufting and crocheting; she unravels garments, draws

In Kari

Steihaug’s art, what is overseen plays a major

Steihaug uses techniques such as knitting, darning,

Editor Nina M. Schjønsby

oeuvre and draw up the lines of a varied and rich practice.

prose contributions provide introductions to Steihaug’s

In this book 25 years of her work is collected. Poetry and

ISBN 9783897906846

Editor Nina M. Schjønsby

Editor Nina M. Schjønsby

After the market (2009). Installation: Unravelled wool garments, knitted image after the painting The Gleaners (1857), Jean-Francois Millet. The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo

After the market (2009). Installation: Unravelled wool garments, knitted image after the painting The Gleaners (1857), Jean-Francois Millet. The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo