THE MANY FACES OF UKRAINE

We do not seek, we look. This became the motto for our exhibition. It came about as we were making preparations and gathering material, in discussions with artists, while searching archives, collections and libraries that were not accessible because of occupation, destruction and the general war situation in Ukraine. Kaleidoscope of (Hi) stories is an attempt to approach and describe Ukraine through its art.

Historically, Ukraine emerged under the influence of the different states to which its territory belonged. A range of artistic, cultural and ethnic influences produced a colourful fabric that is reflected in the country’s complex, layered identity. But what exactly is that identity? It is a concept that constantly changes, especially in the case of Ukraine. We cannot pinpoint any generally applicable universal paradigm for the manifestations of Ukrainian identity, the development of the country and its art. The identity of Ukraine continues to change. To this day, Ukraine has many faces. We regard the exhibition as an environment in which we are able to think about our own cultural heritage in all its cultural and geographical multiplicity, and to understand it – for the development of art and culture in the various regions of Ukraine is related to a range of historical paradigms and connotations.

Kyiv, a city with a long history, the home of St. Sophia’s Cathedral with its unique examples of Byzantine art, is where Mykhailo Boychuk’s (1882 – 1937) original school of monumental art was located. The modernist and, to some extent, constructivist art of the 1920s is particularly significant to Kharkiv, and and to Odesa is the myth of the unique, multicultural, “Mediterranean”

detail p. 86

city. The situation is entirely different in Lviv, which only became part of the Soviet Union in 1939, and where there was sporadic military resistance until the mid-1950s. The regions in the east and southeast of Ukraine, like Zaporizhzhia and Dnipro, with their industrial economy, were the cradle of Ukrainian anarchism in the 1920s, and the major miners’ strikes in Donetsk in 1989-1990 can be seen as the beginnings or the awakening of Ukrainians’ current political awareness – the start of their struggle for civil rights and a civil society. This has become especially clear in recent years, since the Revolution of Dignity in 2013–2014.

All these internal disputes and conflicts highlight the kaleidoscopic aspect that is reflected in the title of the exhibition. The kaleidoscope is a natural metaphor; every time the angles change, new images emerge. These changes of perspective are also important in the exhibition, the perspective in respect of history, experience and artistic practice. The four main themes of the exhibition – Practices of Resistance, Culture of Memory, Spaces of Freedom and Thoughts about the Future – flow seamlessly, inviting visitors to take a journey through a complex collection of different experiences and histories that bear witness to the multifaceted but shared history of the country.

Ukraine is now developing a new character despite – or because of – the war, but at any rate in connection with it. As we are confronted with that which has remained unsaid, which is uncomfortable and complex, it is art that enables us to recognise new paths, and to take our first steps upon them.

Oksana Pavlenko

Long Live March 8! | 1930-1931 | oil on canvas | 150 x 115 cm

National Art Museum of Ukraine

PRACTICES OF RESISTANCE

Resistance. It means first and foremost disagreeing, adopting a position at odds with prevailing conventions and abandoning clichés enshrined in ‘public opinion’. Resistance arises from the need to defend the right to life, work and creativity, to withstand violence, injustice and oppression – political, psychological and social. Acts of resistance occur when a stable system is threatened, prompted by disruptive life events, war and other mechanisms that subvert the normal order of things.

Art as resistance takes various forms, and encompasses a range of methods, from agitation and propaganda, to the occupation of the public space and protest against established norms that curtail the freedom to think, live and act.

In Ukraine art bears witness to tumultuous revolutions and gives a good insight into the politicised reality and the controversial events associated with it,1 resulting from the struggle for self-determination. Ukraine has repeatedly faced hostilities within its borders.

‘... in January 1918, when Kyiv was under heavy artillery fire, we were painting from life. One of the most dedicated female models came to pose for us regularly, and the bravest students worked every day. An artillery grenade hit the bottom floor of the building which was housing a hospital at the time. The heavy explosion threw the students and models, and their easels and palettes, to the ground…’,2 artist Oksana Pavlenko (1896 – 1991) recalled of this event.

In his screenplay Ukraine in Flames, Oleksandr Dovzhenko (1884 – 1956) described the tragic destruction of Ukrainian land during the Second World War: ‘They (Nazi forces, ed.) lined up whole families and shot them, as they set their homes on fire. They hanged people, laughing like idiots, pursued women, took their children from them and threw them in the flames. […] The hanging bodies on their

terrible gallows still swung, casting unforgettably hideous shadows on the ground. The entire village was on fire. Everyone and everything that could not flee in time to the forest, to the reed beds, to the secret hiding places under the ground – everything perished.’3

A reality such as this, so it seems, should be preserved in the darkness of history, passed from generation to generation in the form of someone’s narrative, a personal recollection, bringing with it a trail of cruelty in order to prevent any renewed instances of dehumanisation. But this is now a hard reality again. Today’s Ukrainian cities are once more the scene of hostilities.

Violence, blood and conflict define the familiar backdrop against which art in Ukraine has developed, and continues to develop, in the 20th and 21st centuries. This seems to be an oft-repeated pattern anywhere in the world where art faces totalitarianism, civil war, oppression and political imprisonment.

In the post-revolutionary 1920s the work of artists like Leonila Hrytsenko (1909 – 1992), Viktor Palmov (1888 – 1929) and Oksana Pavlenko was about opposition to global historical injustice and the Tsarist regime of the Russian Empire. Their art was imbued with a belief in global revolution.

Oksana Pavlenko was not understood by the farming community she came from, where art was held to be something exclusively for the elite. She first had to assert her right to be an artist. Later, when she was studying in Mykhailo Boychuk’s (1882 – 1937) monumental painting studio, the future artist was once again confronted with inequality: ‘Boychuk very reluctantly accepted girls to the studio and resolutely refused to accept me at first. His motivation was that girls were inherently unreliable. He would spend time and effort on them, and then they would marry and abandon art… But I was patient and

Leonila Hrytsenko

An Episode From The Civil War | 1931 | oil on canvas | 60 x 77 cm National Art Museum of Ukraine

Boris Mikhailov Untitled | from the series The Theatre of War, Second Act, Time Out | 2013-14 | c-print | 180 x 130 cm | Akademie der Künste Berlin, Kunstsammlung

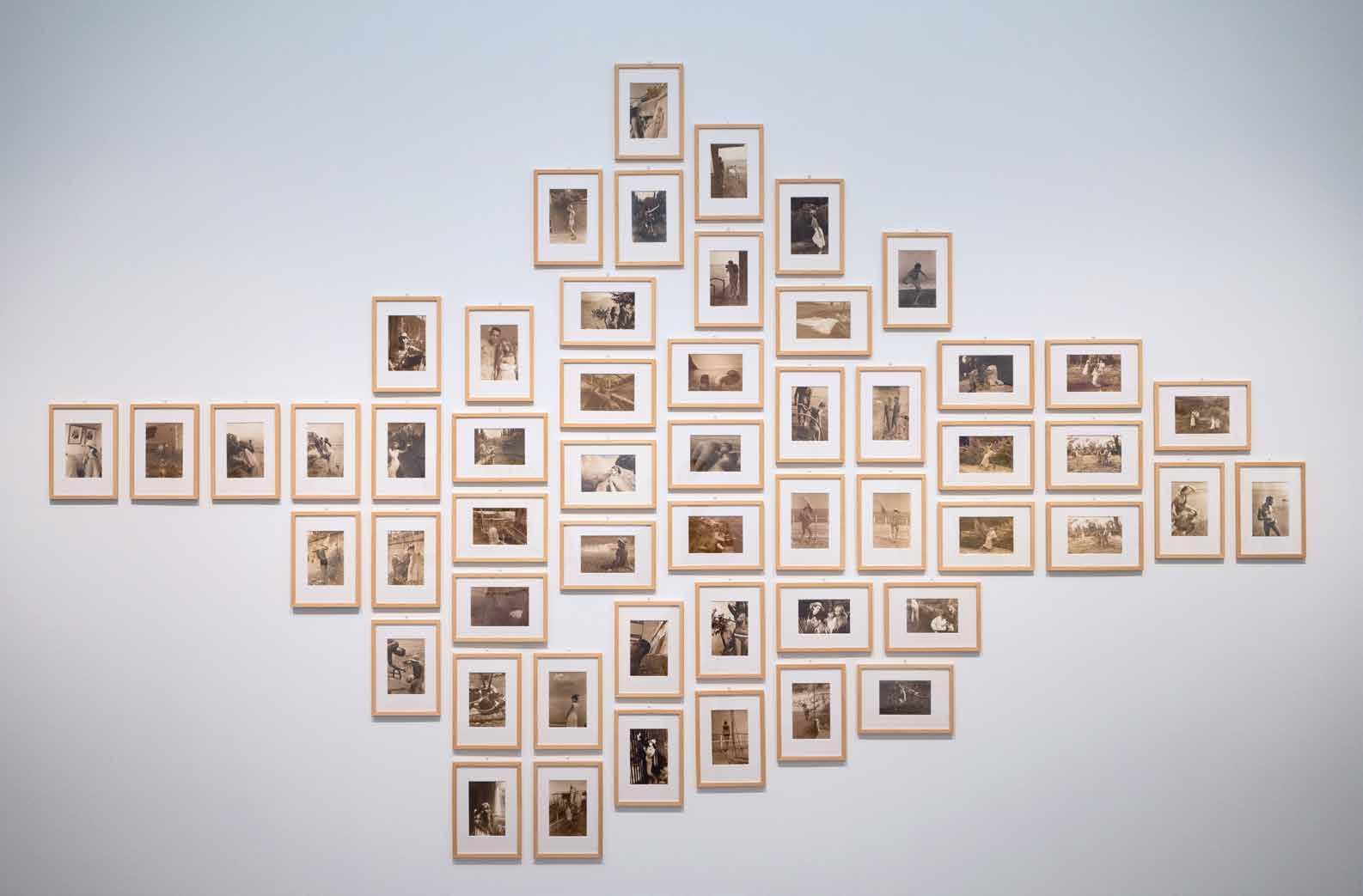

Boris Mikhailov Crimean Snobbism | Installation view, Kaleidoscope of (Hi)stories, Albertinum, Dresden

THOUGHTS ABOUT THE FUTURE

In the realm of artistic production and exhibition making, we strive to maintain a delicate balance between exploring the possibilities of futuristic “other worlds” and staying grounded in the reality of the world we inhabit.

An editorial essay in the online journal e-flux titled “Other Worlds” warns against the peril of losing ourselves in these alternate realms, emphasizing the importance of staying connected to our present existence. This notion holds particular resonance in the current Ukrainian situation, where artists grapple with the ongoing war and its profound impact on their lives and creative endeavours.

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine has not only inflicted immense suffering and destruction but also transformed artistic production into a means of bearing witness to war crimes and offering solace to those affected by the conflict. Despite the loss of cultural heritage, Ukrainian artists persist in creating in the present, enriching their work with layers of complexity. However, the challenges posed by war and the struggle for survival have made it exceedingly difficult, if not nearly impossible, for them to envision a future. The prevailing uncertainty and trauma that pervade their daily lives overshadow any thoughts of what lies ahead.

One artist who exemplified the resilience and adaptability of Ukrainian artists was Fedir Tetianych (1942–2007). He was a visionary who dedicated his life to developing a project called the “Biotechnosphere” as a space for future human civilization. Within his doctrine of “Frypulia,” Tetianych combined scientific and technological advancements with the life-giving potential of the Earth. His creations included peculiar flying apparatuses

designed for space travel, with the ultimate aim of enabling eternal life for humanity. The biotechnosphere, according to Tetianych’s imagination, took the form of a spherical object with a diameter of 240 cm. It was envisioned as an ideal autonomous space for human existence, serving as a refuge in the event of catastrophic disasters on Earth or the malfunction of the flying machines themselves. Tetianych materialized one of the first biotechnospheres using found materials, which he installed in his garden in the village of Kniazhychi near Kyiv. Remarkably, he also succeeded in creating independent biotechnospheres as public artworks. These representations, sometimes subtly veiled and other times openly displayed, became integrated into his monumental mosaics and paintings. Tetianych was also commissioned by the government to construct a metal-cast biotechnosphere for the monumental design of a railroad depot in the city of Popasna, located in the Ukrainian region of Luhansk.

Tetianych’s visionary creations and his integration of the biotechnosphere concept into various artistic forms demonstrate his commitment to exploring the possibilities of the future and the symbiotic relationship between humans, technology, and the environment. His work stands as a testament to his imaginative vision and his contributions to the artistic landscape of Ukraine. Dana Kavelina, borrowing visuals from Tetianych’s Biotechnosphere, embarks on a philosophical exploration of utopian ideals. Her work It cannot be that nothing can be returned (2022) is a thought-provoking sci-fi video that immerses viewers in a utopian future world. In this envisioned future, the societal landscape undergoes a profound transformation, eradicating the concept of

Sergey Bratkov Konstruktivismus | 1996 | c-print | courtesy the artist