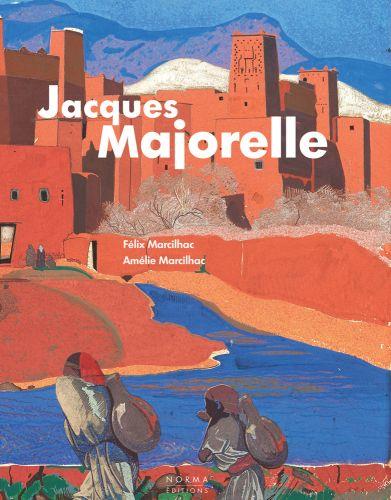

8 François Chomel, Serge Majorelle, Michel Hamann-Pidancet Introduction 12 Félix Marcilhac Formative years 14 France 16 Spain—24 Italy—28 Egypt—34 Morocco 48 The first years—50 A painter’s journal—70 Settling in Morocco 84 Marrakech, the red city 92 Exhibition: L’Exposition des Arts Décoratifs in Paris (1925)—114 Contents Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 11:59 Page6

Forewords

Route of the kasbahs 116 Exhibition: L’Exposition Coloniale in Paris (1931) 134 Nudes—136 Casablanca Town Hall—154 Mixed media—158 Journeys in Africa—168 Ivory Coast, Guinea, Senegal, French Sudan (1945–1952) 170 The last years—184 Jacques Majorelle, painter of Marrakech 186 Catalogue of work—200 Chronology 339 Bibliographical references 344 Index —348 Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 11:59 Page7

Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 11:59 Page10

For my lifetime friend, Jacqueline

Foissac

Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 11:59 Page11

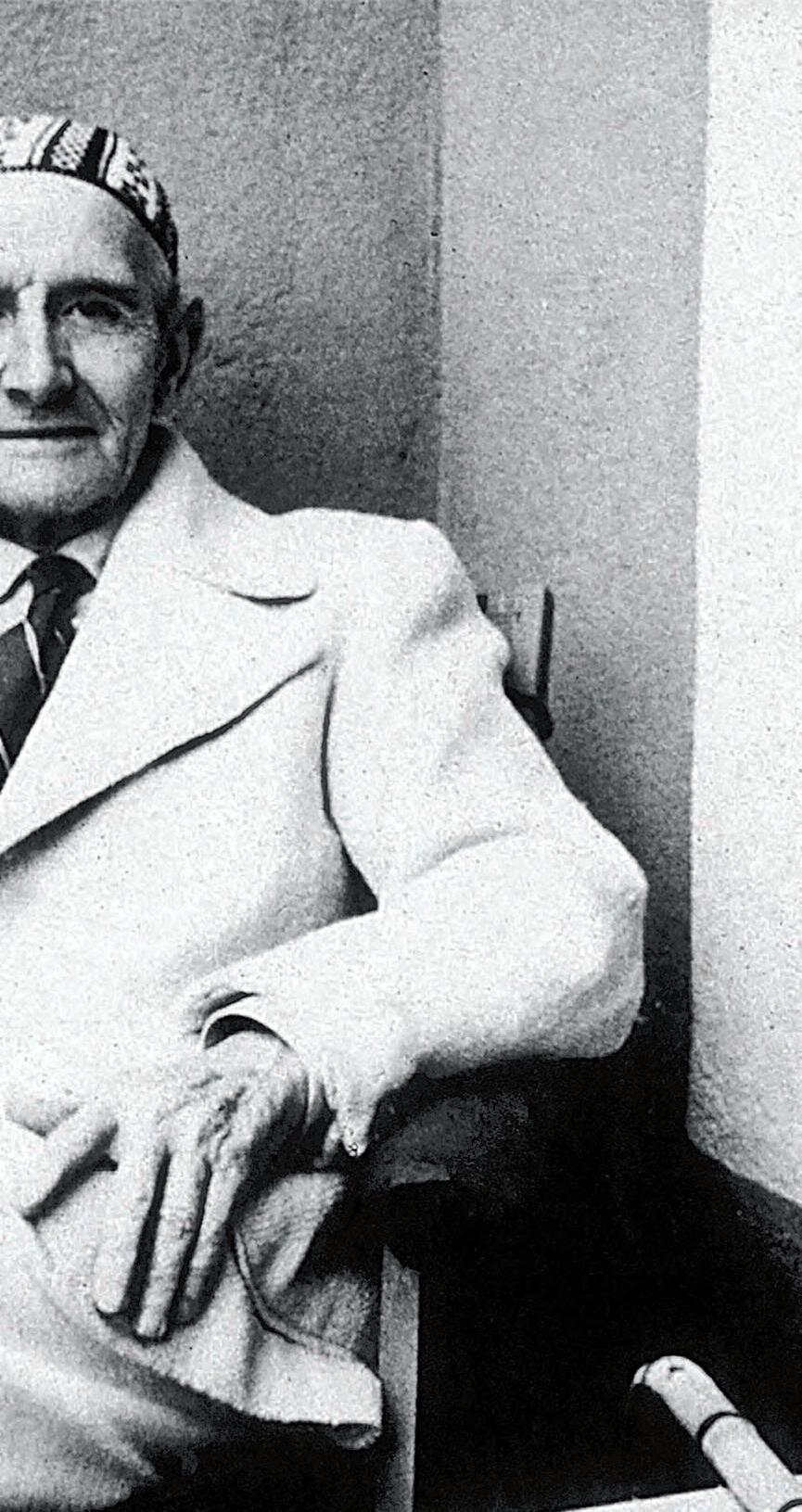

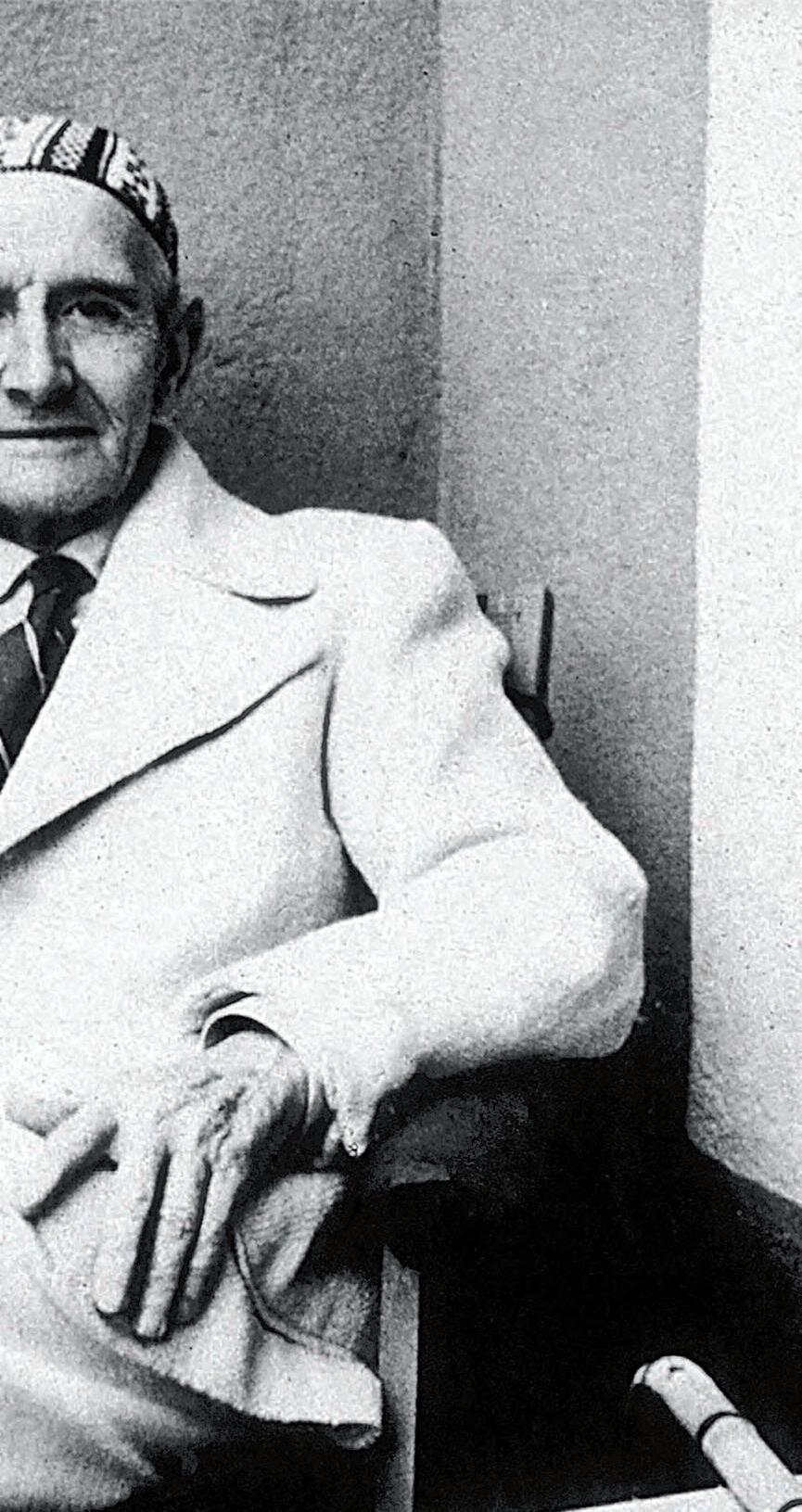

Jacques Majorelle on the terrace of the Bou Saf Saf villa, c. 1955.

Itwas by chance, or perhaps not so much by chance, that I discovered Morocco in December 1969, and in particular, the city of Marrakech. I had been invited by my friend Jacqueline Foissac to spend the New Year holiday at her house in the palm groves. I was to return as a frequent guest several times a year, even in the hottest summer weather, until I became a resident myself by buying a house in 1991.

My enthusiastic discovery seemed predestined. After all, wasn’t I already passionate about the works of Orientalist painters and especially the works of Jacques Majorelle, the son of a cabinetmaker from Nancy? From my very first visit to the souks of Marrakech the day after my arrival, I had the strange sensation of having been there before. All seemed familiar: the bakals, the fondouks, the derbs, the stalls with their customers, and even the women with their white veils and traditional clothes. I was fascinated by it all: by the dyers’ souk with its skeins of wool hanging by ropes; by the souks selling spices and dates, or skins; by the tinsmiths, coppersmiths and straw sellers; and by the souks with babouches, djellabas and silks. Of all these labyrinths of beaten earth that lead from one district to another, the most obscure or the dustiest or the most twisted that could seem worrisome to step into, not one seemed unknown to me. In the alleyways, the sun pierced through the clumsily made cane coverings until the dazzling brightness of its rays blinded me.

Intrigued by this sensation of déjà vu, I had to go back several times in a row until I realised that the memory I had of Jacques Majorelle’s paintings had come to bear on my own discovery of the city, on my vision of the moment and my feeling of place. It was all there, the silhouettes of women in caftans that he outlined in painted sketches at the beginning of his stay, the bright colours of their clothes, the market scenes, the transparent dust in the air and even the smells that I could not shake off. Obviously, then, I fell in love with the city, with the turbulence of its medina, the authenticity of its souks, the Menara pavilion and its waterways, as well as the luxuriant palm groves with their greyish-green foliage. All became part of the same memory.

Without being backward-looking, the ambience in the medina, in the souks and even in the provincial aspect of the European city, suited my feelings and my temperament. I felt so much at home that I adopted the way of life peculiar to Marrakchis, who put off until tomorrow that which they have not found time to fit into the special rhythm of today.

Years ago, there were hardly any buildings in the palm groves. There were a few farms made of pisé that had crumbled into the vegetation, a few sheep, donkeys and mules in the shade of the olive trees, and four or five houses without electricity, dating from the 1930s, that Europeans had built outside the land registry’s authority

12

Introduction Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 11:59 Page12

and that were served by almost untraceable dusty trails. Local legend had it that in centuries gone by, soldiers camped outside the city walls with only dates to live on and left the stones behind. When the stones germinated, they grew over decades into huge palm trees. The area was wild, almost untouched, and had great beauty. It was here that Jacques Majorelle built his own villa, just outside Bab Doukkala, one of the ten open gates in the pisé ramparts surrounding Marrakech and located in the northwest of the ancient city. Blessed with an extraordinary, exotic garden, he would enrich it every year with unusual plant species that he brought back from his journeys into the Atlas Mountains and deeper into Africa, with the idea of exchanging plants with other botanical gardens across the world.

I really owe my initiation into Morocco and life in Marrakech to Jacques Majorelle, to his paintings of the Atlas kasbahs, to his fascination for scenes of daily life in the souks and to the welcome given by the inhabitants of this marvellously hospitable country. All have nourished my soul and fed my imagination.

In November 2016, I met Jika, the eldest daughter of Jacques Majorelle, thanks to the kindness of her son François. Through him, I made the acquaintance of a delightful white-haired lady who bubbled over with happiness as she recalled the father she had loved so well, his paintings of which she had a formidably precise memory, and the Bou Saf Saf villa with its beautiful garden where she grew up. This catalogue of Jacques Majorelle’s works sets forth in its biographical section the outline of our previous work dedicated to this painter that appeared in 1988 and was reprinted in 1995. It is enriched here with clarifications drawn from a variety of correspondence of the artist with his family and friends, and from his personal journals written in Spain, Italy, Egypt and Morocco. There is also a list of the various paintings and works verified during our research of almost fifteen years that comprises 1,055 indexed records, each with a photograph. Thanks to the welcome participation of the Fondation Jardin Majorelle and of Pierre Bergé and Madison Cox, who is involved with the publication of this edition, the book has been published by Norma in 2017. It fulfils the promise made at the end of the 1970s in Marrakech to MarieThérèse Majorelle, known as Maïthe, the artist’s second wife, to publish a book on the works of this great painter as faithful witness to a traditional Morocco that has been brutally dragged into today’s world.

13

Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 11:59 Page13

Félix Marcilhac, Marrakech, February 2017

1 2 3 4 Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 11:59 Page14

Formative years 1

1. Jacques Majorelle on holiday in the Loiret, L’Ortie villa in 1911.

2. Jacques Majorelle in 1907.

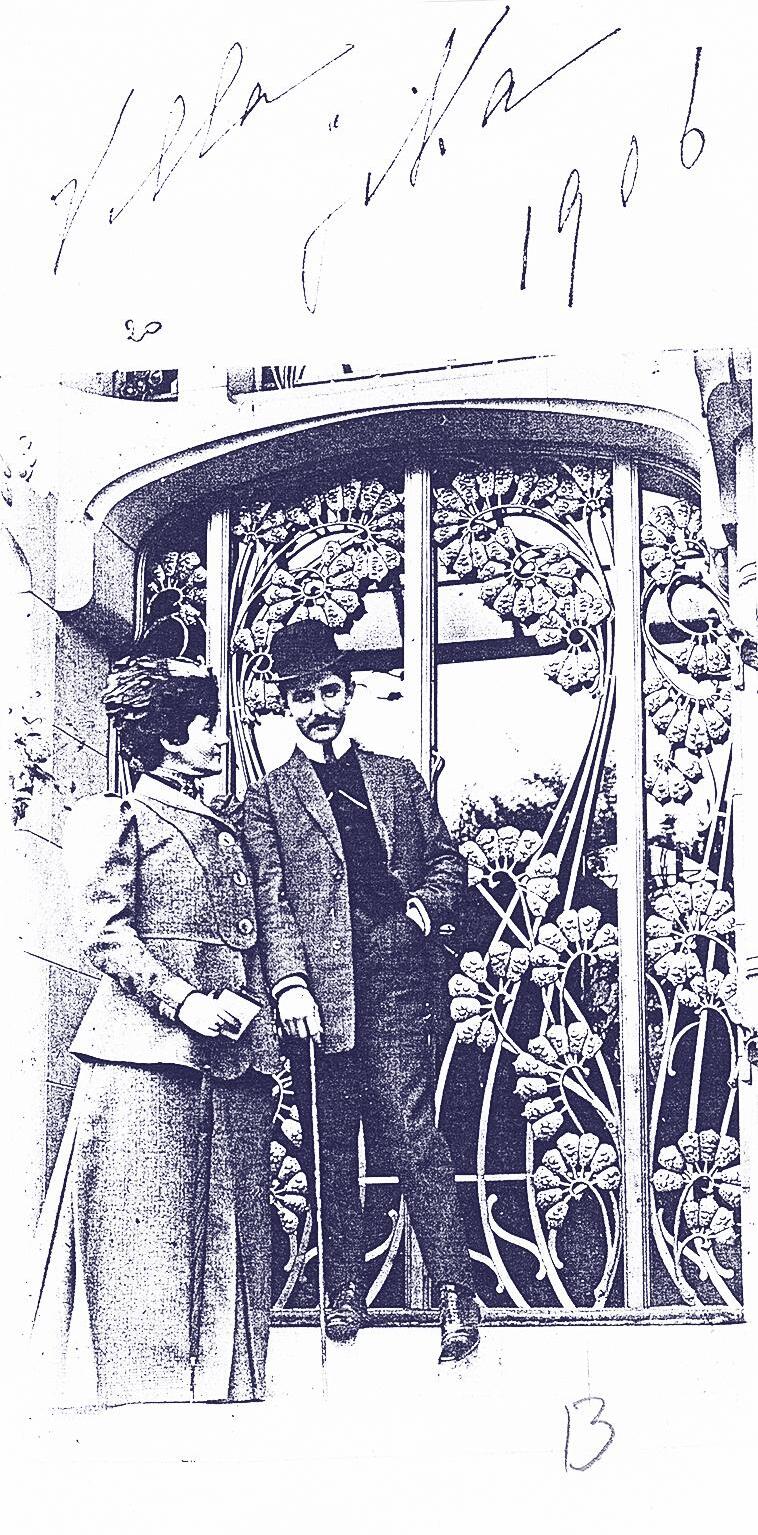

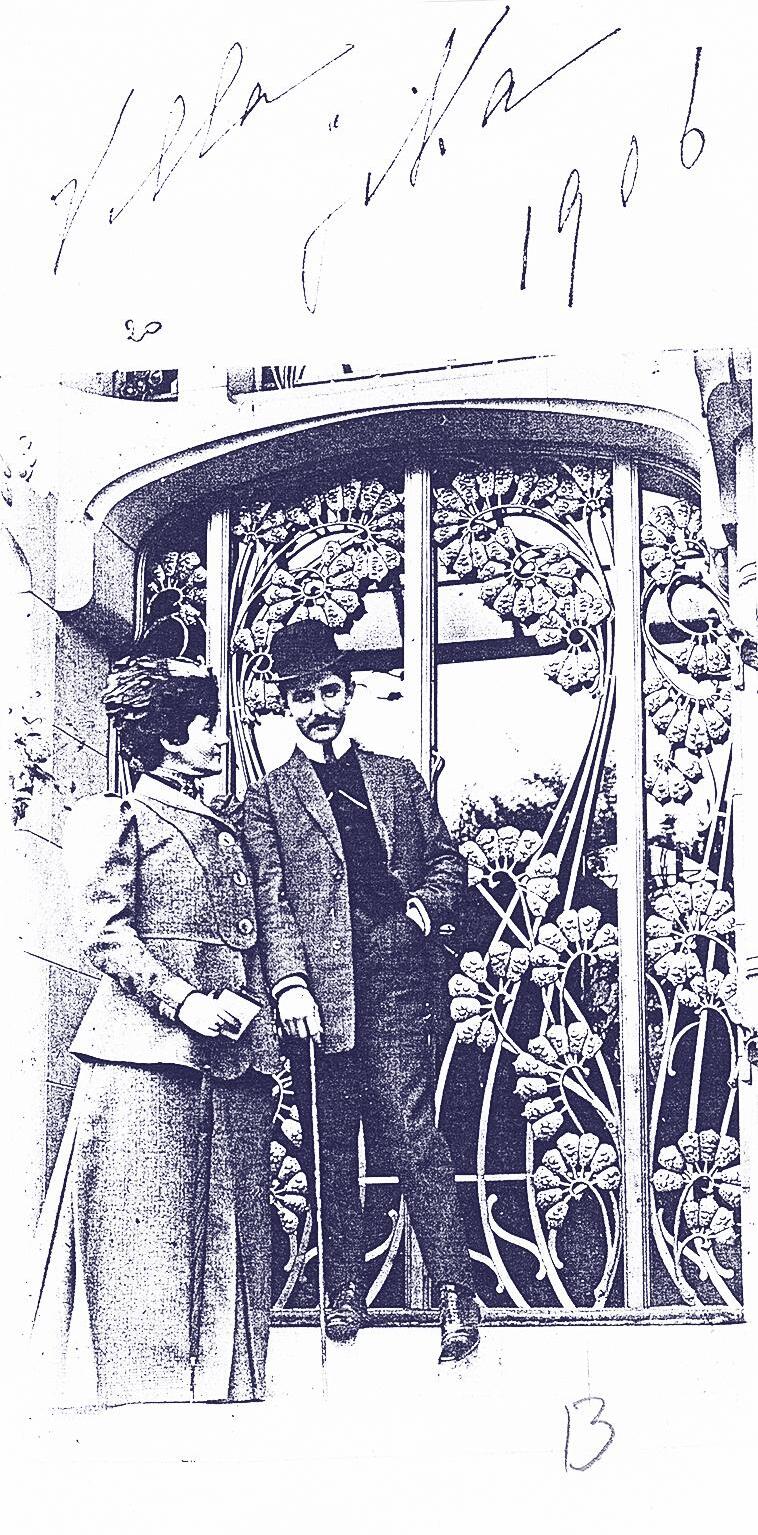

3. Jacques Majorelle with his mother on the terrace of the Jika villa in 1906.

4. Jacques Majorelle as a young schoolboy in Nancy, c. 1895.

5. An artist’s afternoon, c. 1904.

6. Jacques Majorelle in a tent in Egypt, c. 1914.

7. Jacques Majorelle in Paris in 1934.

1. Jacques Majorelle on holiday in the Loiret, L’Ortie villa in 1911.

2. Jacques Majorelle in 1907.

3. Jacques Majorelle with his mother on the terrace of the Jika villa in 1906.

4. Jacques Majorelle as a young schoolboy in Nancy, c. 1895.

5. An artist’s afternoon, c. 1904.

6. Jacques Majorelle in a tent in Egypt, c. 1914.

7. Jacques Majorelle in Paris in 1934.

Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 11:59 Page15

5

6 7

Atthe end of the nineteenth century, Nancy reclaimed the creative activity that had made it the great artistic capital of eastern France in the preceding century. After the war of 1870, the annexation of Alsace and part of Lorraine by Germany had brought about a kind of renaissance in the part of the town that remained French. Many artists, artisans, intellectuals and members of the arts professions from the annexed regions sought refuge here so that they could remain French. They preferred to abandon Metz, with its military and industrial activities that were less attractive to them, in favour of Nancy, whose cultural past was more appealing. It was said at the time that Nancy was the “soul” of Lorraine while Metz was its “heart”. August Majorelle’s family came from the town of Toul which, along with Metz and Verdun, was one of the three bishoprics annexed to France from 1648 by the Treaty of Westphalia. They came to live in Nancy in 1860. Auguste Majorelle, grandfather of Jacques Majorelle, opened an art and décor workshop in the Saint-Pierre district. The eldest son, Louis, born on 27September 1859, had been taking a design course for a year before leaving Toul and continued after his arrival in Nancy at a school directed by the painter Devilly, as well as starting to do ceramics. He was the first of the eight children of Joseph Constant Auguste Majorelle and Marie Jenny Barbillon. Highly talented in the fine arts, with the approval of his parents, Louis Majorelle left for Paris in March 1877 and enrolled at the School of Fine Arts. He was a faithful student at the studio of Jean-François Millet. This master was already sixty-three years old and his huge talent was recognised as much overseas as in France. In 1879, the premature death of Auguste Majorelle forced Louis to interrupt his painting studies and return to Nancy. Had this terrible event not happened, Louis would without doubt have followed another destiny, much like his friend Victor Prouvé, also a Devilly student, who followed him to Paris to enrol in July 1879 at the School of Fine Arts in the

studio of Alexandre Cabanel. In any case, when he got home, Louis Majorelle took over the management of his father’s workshop. He was just twenty years of age. On 7April 1885 in Nancy he married Marie Léonie Jane Kretz, born 6 December 1864 in the same town. She was the daughter of Joseph Kretz, the theatre director in Nancy. They had just one son, Jacques Majorelle, born on 7 March 1886.

Specialising in reproduction furniture and an interpretation of the traditional Japanese arts, Auguste Majorelle had already won accolades at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878. His two-tier tea tables decorated with flowers and birds in glistening lacquerwork on a base of aventurine had been an enormous success. Little by little, he steered his production towards new, modern furniture, while his brother Jules was busy with the administration of the studios. Applying himself to developing characteristics of the style championed by Émile Gallé, which advocated a “return to nature”, he adapted these features to cabinetmaking. Taking the outdated ideas of his contemporaries in this field and revolutionising them, he triumphed in 1900 at the Exposition Universelle in Paris with furniture made of Courbaril mahogany and gilded appliqué bronzes with water lily patterns of such extravagance that visitors were entranced and art critics happy to applaud. A recognised artist and champion of stylistic revival, he became the uncontested leader within the Nancy School of Art Nouveau furniture. This provincial alliance of industry and arts was founded on 12 February 1901 by a group of Nancy artists. It was a private association presided over from the beginning by Émile Gallé, and then, after his death in 1904, by his friend Victor Prouvé. The aim of the group was to bring life back to the creative industries and the traditional arts of the Lorraine region that had been declining or had disappeared, and to encourage their renaissance.

From the beginning, the association was supported by patrons, of whom the most active was Eugène

16 Formative years

France

Émile Friant, Jacques Majorelle, petit enfant, c. 1888.

Victor Prouvé, Jacques Majorelle, enfant, 1890.

Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 17/08/2017 13:41 Page16

Right-hand page Portrait de mon père, oil on canvas, 114 x 85 cm, 1908. Musée de l’École de Nancy.

17 Formative years Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 17/08/2017 13:41 Page17

Corbin, son of Antoine Corbin, founder of the Magasins Réunis and who, after the death of his father, also took over the family business with his brother Louis. The latter was a childhood friend of Louis Majorelle and had taken the same design course at the city school. Architect Lucien Weissenburger constructed a new building for Magasins Réunis in 1907 in the Place Thiers in Nancy, and Eugène Corbin set aside the top floor for artists from Lorraine. Closed to the public, this floor was generously given over to painters who wished to work there. Board and lodging was provided free of charge and, in exchange, some of the paintings became the personal property of Eugène Corbin. In 1934, he donated his important collection to the city and to the Musée de l’École de Nancy, inaugurated on 25 March 1935. Thanks to this donation, one of the objectives of the Nancy School came into being thirty-four years after its creation: to open a museum to demonstrate the merits of its programme by exhibiting the artwork of its members. In 1963, Jacqueline Corbin, the widow of Eugène, in turn bequeathed her own house on Rue SergentBlandan, to allow the museum to expand by officially becoming the Musée de l’École de Nancy.

Encouraged at the beginning of the twentieth century by such exceptionally innovative talent, the city of Nancy was full of exciting creativity. Bathed in the spirit

of aesthetic research that animated the family home, Jacques Majorelle’s sensitive temperament was easily awakened by the arts and naturally turned him towards an artistic career. In 1890, Victor Prouvé painted a delightful study in oils of Jacques, then aged four. Dedicated “for my friend, L. Majorelle”, the painting showed a child in sailor’s outfit with an attentive face, a lively and sensitive look as befitted the occasion. In 1897, after the new studios were set up on a large piece of land bordered by the streets Goncourt, Vieil-Aitre and Palissot in the hamlet of Médreville, Louis Majorelle built himself a luxurious villa there called Jika, named for the initials, as pronounced in French, of the maiden name of his wife, Jane Kretz. Henri Sauvage, a young Parisian architect with whom Louis Majorelle had already collaborated in the building of the Café de Paris on the Place de l’Opéra in Paris, was chosen to submit the plans and worked closely with Louis Majorelle. A large workshop, the interior architecture of which can be guessed at from the façade, was planned for the master in this vast house. Apart from the ceramic tiles and friezes with floral decoration by the Parisian ceramicist Alexandre Bigot that are affixed to the façade and the interior of the villa, all the architectural elements – the woodwork, ironwork and furniture – were made in the workshops around the Majorelle company.

18 France Formative years

Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 17/08/2017 13:41 Page18

Le Carré de choux, watercolour and mixed media on paper mounted on wood, 53.5 x 70 cm, 1904. Musée de l’École de Nancy. Le Sacré-Cœur en construction, wash tint and watercolour on paper, 39.5 x 44.5 cm, 1909.

A wise industrialist and watchful initiator, Louis Majorelle trained a whole team of artisans in his ideas between 1890 and 1900. They then went on to participate in the transformation of the city of Nancy in developing and decorating most of the buildings that were built before the war of 1914. He also brought into this sphere Alfred Lévy who became director of the workshops, Frédéric Steiner, Eugène Gatelot and François Louis who were sculptors, Charles Jung, cabinetmaker, Alfred Lognon, carver, Jean Keppel, metalworker and Henri Vaubourg, a marquetry specialist.

Jacques Majorelle grew up in this artistic world. It is not difficult to imagine that he was often interested in some specific idea about furniture, or a spectacular piece of ironwork, as he walked about the workshops with his father. It had already been decided within the family circle that he would be an architect, as the teaching of this discipline was considered by his father as a superior expression of art. On 4 October 1901, Jacques was enrolled in the National School of Applied Arts in Nancy, in the faculty of Architecture and Decoration, and given the student number 2,100. The excellent if severe master Jules Larcher oversaw his training during the early years. He taught design and painting. Classical in taste and in temperament, this painter had been a pupil of Charles Sellier and Léon Bonnat in Paris. His teachers launched him at the Salon of 1876. In the same way, he inculcated in the young Jacques Majorelle, who was then no more than fifteen years old, a rigorousness and sense of graphic precision that became the essential characteristics of his work throughout his life. At this school, in addition to classes in modelling and sculpture, the young student also took courses in stylisation and decoration taught by Jacques Gruber, while architecture classes were given first by Charles Bajolet and then by Lucien Bentz.

He graduated from the school on 31 July 1903. After three years of study and despite advice to the contrary from his father, Jacques Majorelle gave up architecture to devote himself entirely to painting, something he had done for pleasure throughout these last years. This training in architecture gave Jacques Majorelle his “aristocratic preoccupation” with line and the precise sense of composition that he went on to develop and that is so wonderfully expressed in the series LesKasbahs de l’Atlas , published in 1930.

Alongside his studies at the School of Fine Arts in Nancy, the young man had had the good fortune to benefit from the counsel of two great painters of the school, Émile Friant and Victor Prouvé, so his path was clear. The first of these was a much respected, scrupulously realist painter of immense talent and the second, of a more lyrical temperament, was much appreciated in the official art world in Paris. Together they could provide a less academic training than that of the school in Nancy. Also, after leaving his architectural studies, Jacques Majorelle took regular painting classes at Émile Friant’s studio on the Rue de Thionville. It was Friant who painted a portrait of Madame Louis Majorelle in 1895. These ties, both affectionate and professional, linked the two families, and Jacques Majorelle remained faithful to his old maître Friant all his life. It was Friant who gave the eulogy at

the funeral of Louis Majorelle in 1926 in Nancy, in the absence of his son, who had stayed in Morocco for health reasons. In that emotionally charged speech, he recalled the privileged rapport his family had had with the son of his friend “who upholds so valiantly the name of Majorelle in his painting”.

Jacques Majorelle’s work Le Carré de choux (1904), found at the Musée de l’École de Nancy, shows that already at this time, he was highly skilled. This large watercolour is both charming and well executed, although not very personal, despite the interesting framing of the cabbage patch depicted at an angle in the foreground. It shows original sensitivity, particularly in the use of a different blue that contrasts with the brilliant yellow. The influence and lyricism of his teachers can be felt, like so many excellent references.

Since birth, Jacques Majorelle seemed to be in fragile health, but at the beginning of 1904 he was summoned before a medical board to complete his national service. His personal record filed on this occasion mentions that he had auburn hair and eyebrows, grey eyes, an ordinary forehead, an average nose and mouth, a round chin, an oval face and that he was 1.67m tall. He was discharged on health reasons, as the doctors had detected early signs of tuberculosis.

émile Friant, Portrait de Jane Kretz, pastel, 58 x 47 cm, 1895. Nancy, musée des Beaux-Arts.

Jacques Majorelle with his father and mother in the garden of the Jika villa in Nancy in September 1911.

Below

Jacques Majorelle as a student in Paris, c. 1906.

Following pages, left Concarneau, oil on cardboard, 17 x 20 cm, 1916.

Right, from top to bottom Concarneau, oil on cardboard, 17 x 20 cm, 1916.

Bateaux en Bretagne, oil on cardboard, 15.5 x 21.5 cm, 1916.

Concarneau, oil on cardboard, 18 x 21 cm, 1916.

In June 1904, the Majorelle company set up business in Paris, Louis and Jules Majorelle having bought the former mansion of Samuel Bing at 22 Rue de Provence in the 8th arrondissement. Samuel Bing had promoted Art Nouveau here since its inauguration on 28 December 1895, but ended up abandoning it in 1903 because his business failed commercially, and also for health reasons. Jules and Louis Majorelle, having had enormous success at the Paris Exhibition in 1900, were looking to extend their business in the capital and approached his son, Marcel Bing, apparently contemplating an association with him, but then proposed to buy back in full his father’s establishment. On 29 June 1904, plans drawn up by Pierre Selmersheim and Henri Sauvage, both architects from Nancy, were submitted to modify the building and interiors, designed in 1895 for Samuel Bing by the French architect Louis Bonnier and his Belgian partner, Henry van de Velde. All the exterior decoration, including doors and windows, was changed, as were the interior floors. In 1910, the shop was enlarged and the height raised by the same architects, to the configuration still seen since then. This temple to Art Nouveau of the Paris School then passed into the hands of representatives of the Nancy School, celebrating on this occasion the triumph of vegetal exuberance in the Nancy style with the restraint and ornamental stylisation of artists Eugène Gaillard, Georges de Feure and Eugène Colonna, whom Samuel Bing had been promoting for about ten years. This triumph lasted until the 1909 International Exhibition of Eastern France in Nancy. In fact, the protagonists, blinded by their commercial success, did not realise that this exhibition really marked the end of the Art Nouveau style in France. While the artists were persuaded of the superiority and merits of their approach and were incapable of renewing a style that within itself carried the seeds of its own demise, Art Nouveau fell victim to the outrageous extravagances

19 France Formative years

Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 11:59 Page19

Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 11:59 Page20

21 Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 11:59 Page21

40 Egypt Formative years Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 17/08/2017 13:41 Page40

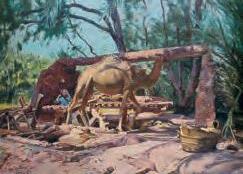

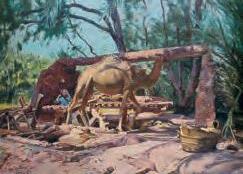

lutely not moved by the established landscapes … quite frankly, the pyramids bored me to death, the sunset was magnificent but the forty-one centuries observed my disappointment.” Situated in the middle of a palm grove, “Marg is teeming, stinking and full of colour”. A brackish stream ran around it, its banks dripping with indefinable tones, as he described it. There, women did washing and bathed, and camels drank. Marabout à Marg (c. 1911), Marg, effet de crépuscule (1910), Marg, scène de village (c. 1911) and Chamelier à Marg (c. 1911) are appealing works dating from this first visit. They are painted with muted colours, stronger and with more contrast than those used in Venice, his remarkable discovery of these picturesque, unspoilt places, bathed in light, having no connection with the tourist sites so dear to foreign visitors. Quick to apply his fleeting impressions to his studies and painted sketches, his touch was wide and generous, with warmer tones to support a drawing that was very present and that emphasized the structure of his compositions. Always keen on accuracy and the absolute, his talent was fully assured here. In other paintings women appeared, swathed in black rags, the lower part of their faces modestly veiled, like furtive shadows (Soir à Marg, 1911). All these small studies and paint sketches on panels are carefully dated on the back, the artist even noting the hour and the day on which they were painted, as if they were to serve as points of reference for the paintings he would do in the studio. In fact, he never revisited these Egyptian sketches, always finding other places, other aspects to satisfy his passion, so they only served to fix in his memory the effects of the light. “I still don’t have anything in sight for the big painting; I have to think about it,” he wrote to his father on 17 December 1910 as the latter was planning to travel to Egypt, accompanied by his wife, to visit in February 1911, as can be seen in several family photographs taken in Matarieh and dated March 1911. In one of them, the artist can be seen smiling with his cheerful father, who was wearing a felt hat and dressed in a suit, with a background of palm trees. It seems to have been at this time, going ahead of his parents to meet them in Athens, that

Le Nil près de Louxor, Egypt, oil on canvas, 50.5 x 134.5 cm, 1913. Sakieh, Egypt, gouache on cardboard, 78 x 106 cm, 1910. Louxor, porteurs d’eau, Egypt, oil on canvas, 45 x 54 cm, 1914. Left-hand page Marg, Égyptiennes, oil on canvas, 162 x 127 cm, 1912. Musée de l’École de Nancy, donated by Eugène Corbin.

Jacques Majorelle visited Greece with them, but without making any paintings or sketches to record this visit.

In an article published in L’Art Vivant in October 1930, after an interview with Jacques Majorelle, Jean Gallotti, who was the director of fine arts and historical monuments in Morocco, referred to these first years spent in Egypt. “This first contact with the exotic was enough to make him understand the malaise that affects the sensitive spirit confronted with spoilt beauty. In Egypt, there were no doubt the palms, the Nile, the sun and that blazing whiteness that calm the immutable. But there were also the grand hotels, the caravans of tourists, the American-style streets of Cairo splitting apart the old Arab districts, there was the sorry sight of the dying local colour. Where to go?” Like so many other painters of this time who followed the Impressionist movement, which revolutionised their artistic vision, the young Jacques Majorelle came here to seek out the light, the colours and the strong sensations but, as much through his independence of character as his personal taste, and drawing from his sense of observation and his humanist approach, he wished above all to show local life in his paintings rather than falsely idealised representations. Also, as his pictorial technique evolved, his interpretations increasingly took on the poetic and lyrical aspect of Victor Prouvé’s painting without completely abandoning the scrupulous realism taught by Émile Friant. This duality is particularly emphasised in Marabout à Marg (c. 1911). The architecture here is present, precise and linear even though the people depicted in the foreground on the banks of a stream are simply drawn. The trees around the marabout, like the surface of the pool, have a vague treatment and perfectly translate this balance of strength through their tonality. Defining the space, the light vividly glances off the angles of the architecture and fades out on the flat surfaces. Majorelle’s view of authentic simplicity seems true to life, without the pretence of the imaginary or the interpretive, while his sensitivity is unconnected in any way with the multiform Orient so dear to painters of the nineteenth century. No doubt he remembered those snatched, spontaneous visions

Formative years

41

Egypt

Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 17/08/2017 13:41 Page41

brought back from Tunisia by his teacher Émile Friant. Aware of the interest and importance of Arab culture that shaped the modern-day Middle East, he came quite naturally to appreciate scenes of everyday life. Women washed their clothes, carried baskets on their heads and went casually about their daily chores against a backdrop of charming, authentic village scenes. Does this not evoke the work of Émile Bernard discovering Egypt during his first stay in 1893, depicting the inhabitants of districts in the old city of Cairo? Just like him, abandoning all desire for Europeanisation, Jacques Majorelle banished from his canvases all studio accessories and objets d’art from the bazaars, all the carpets, lanterns, brasses and formal costumes so dear to painters of the nineteenth century, so that he could simply represent a humbler world, each detail of clothing or architecture retaining its traditional, picturesque character. Men dressed in their djellabas and women enveloped in their black veils are honestly placed in their usual environment without their belonging to some Western vision. Rather than painting a vast narrative work, he concentrated on one theme ( Marabout à Marg , 1912) or on one specific subject ( Cimetière à Marg , 1912) that he would integrate into one painting in which the composition is resolutely original (Soir à Marg, 1911). However, this did not lead him to paint strictly architectural aspects, but when he did paint them, they were for him only a pretext to express

Formative years

his fascination for Arab culture and for the authenticity of the subjects that he transposed in his studies and his painted sketches (Ruelle à Marg, soir, 1912). Most of the works from this period are painted with muted colours that highlight washed-out greens and omnipresent yellows, shadows emphasised with blues and browns. Forsaking the grandeur of landscapes with wide horizons and majestic ruins, Jacques Majorelle asserts himself as an intimist painter for whom each detail retains its traditional character and its own emotional charm. A tomb serves as the frame for fruit or vegetable sellers, the architecture of a house provides the support for street scenes (La Maison rouge à Marg, 1911) in which he focuses his interest on the beggars sitting on the ground, or on the water sellers who wander the streets (Louxor, porteurs d’eau, 1914). Children run and black-veiled women lurk mysteriously in his paintings (Marg, scène de village, 1911). The earth, the vegetation and the opaque transparency of the air are extraordinary evocations. Understanding perfectly the importance of water in this land of sun, he made sure it was represented on every occasion (Le Ruisseau, Marg, 1912; Femmes au bord du Nil, 1912).

He discovered the pyramids of Giza as a simple tourist ( Pyramides de Gizeh , 1911) and went there on a camel: “Advancing silently along the rose-pink sand veined with shadows, carefully balanced and feeling immense pleasure, I first saw the glorious triangles

42

Louxor, la chapelle de Kerfons, Akaris and Massif montagneux, Egypt, triptych, oil on canvas, 21.5 x 27 cm each, 1914. Mathias Ary Jan collection.

Egypt Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 12:00 Page42

Jika and Jacques Majorelle in Matarieh, Egypt, March 1911.

bathed in light, then fading and losing definition in the dusk, only to be brought back to life under the pearly moonlight” ( Sycomores, or Soir aux pyramides de Gizeh , 1911).

His mother died on 31 December 1912 when she was only forty-eight years old. He was profoundly distressed and quickly returned to Nancy. Prolonging his forced return by several months, he took the opportunity to participate in the 1913 annual Exhibition of the Société des Artistes Français in Paris, where he exhibited Esclave (no. 1,178), a painting clearly painted in Egypt, the exact location unidentified to this day. The following November in Nancy, he exhibited four paintings at the 49th annual Exhibition of the Société lorraine des Amis des Arts: Esclave (no. 153), which he had already shown in Paris, and Parure d’Orient (no. 155bis). Next to these two Orientalist paintings were two portraits he had painted during this sad time: Mademoiselle M.M. (no. 154) and Mademoiselle S.M. (no. 155), featuring his two first cousins, Marie and Suzanne Majorelle, two of the daughters of Jules Majorelle, his father’s brother.

Meanwhile, he had completed the large composition mentioned in his correspondence with his parents at the beginning of 1911, Marg, Égyptiennes (1912). No doubt this corresponds to a specific request that Eugène Corbin made of the artist before his departure for Egypt,

as it is one of the works in his personal collection that he donated on his death in 1935 to the Musée de l’École de Nancy. This large oil on canvas depicts three women dressed in black in the foreground, and behind them, a village scene and Islamic architecture. Harmoniously drawn among the heavy twisted branches of a sycamore is a very colourful caravan halt with camels and people at rest in the background. The shadows emphasise the precise line of the design while a bright light dazzlingly washes over the marabout and that whole section of the composition. In sharp contrast with the muted tones of the foreground, black and dark blues, hints of lighter tones are used elegantly in the village scene.

Jacques Majorelle returned to Egypt in the winter of 1913–1914 and travelled the Nile to Upper Egypt. Passing through Tahta south of Asyun, he spent some days at Gebel-el-Tarif to produce several paintings of this mountainous massif ( Coucher de soleil, Gebel el Tarif ). Then, continuing on to Ballas (Rue à Ballas) and Nakadah (Coucher de soleil), he finally arrived at Luxor (Louxor, la chapelle de Kerfons) and Karnak (Temple de Koms). Some of these were painted from the bridge of the boat during the crossing. They depict views of the banks of the Nile during the day or at dusk (Gebelein, les rives du Nil). Stopping off at villages close to tourist sites that he visited with his guide, he painted their inhabitants in situ, depicting their daily activities (Louxor, porteurs d’eau) or

43

Formative years

Egypt Maj 1 -47 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 12:00 Page43

Louis Majorelle and his son Jacques in Matarieh, Egypt, March 1911.

Maj 84-133 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 12:07 Page100

101 Maj 84-133 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 12:07 Page101

Le Marché aux dattes, Marrakech, distemper, mixed media on black paper with highlights of pastel and gold and silver metallic powder, 88 x 108 cm, 1940–1945. Mathias Ary Jan collection.

Souk couvert, Marrakech, mixed media on paper, 53 x 63 cm, 1950.

Bakal et porte dans les souks, gouache on canvas, 50.7 x 63.5 cm, 1955–1960.

Right-hand page

Souk à Bâb Debar, oil on canvas, 45.8 x 55.5 cm, 1921.

Souk couvert, Marrakech, mixed media on paper, 53 x 63 cm, 1950.

Bakal et porte dans les souks, gouache on canvas, 50.7 x 63.5 cm, 1955–1960.

Right-hand page

Souk à Bâb Debar, oil on canvas, 45.8 x 55.5 cm, 1921.

Morocco 102 Maj 84-133 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 12:07 Page102

Marrakech, the red city

Marrakech, the red city Morocco 103 Maj 84-133 OK.qxp 07/08/2017 12:07 Page103

160 Mixed media Morocco Maj 134-167 KO.qxp 07/08/2017 12:12 Page160

161

Mixed media

Marchands de dattes dans le souk, Marrakech, distemper, mixed media on black paper with highlights of gold and silver metallic powder, 97 x 116 cm, 1940–1945.

Femmes berbères présentant leurs tapis sur le souk, gouache and pastel with highlights of gold metallic powder, 86 x 100 cm, 1936–1938.

Morocco Maj 134-167 KO.qxp 07/08/2017 12:12 Page161

Femmes berbères au souk el Khemis, distemper, gouache and pastel on black paper glued to canvas, mixed media with highlights in gold metallic powder, 87 x 104 cm, 1936–1938.

Égypte Maj 134-167 KO.qxp 17/08/2017 13:53 Page164

Procession un jour de Moussem, Marrakech, distemper, mixed media with highlights of gold and silver metallic powder, 71 x 100 cm, 1936–1938.

Page 162

Le Charmeur de serpent, tempera gouache, mixed media on black paper with highlights of gold and silver metallic powder, 105 x 76 cm, 1935–1940.

Page 163

La Danse du guerrier, pastel and gouache, mixed media on paper with highlights of gold and silver metallic powder, 56 x 71 cm, 1936–1938. Marché à Marrakech, oil on canvas, 80.5 x 77.5 cm, 1940–1945.

165

Maj 134-167 KO.qxp 17/08/2017 13:53 Page165

Authors’ acknowledgements

We thank Michel Hamann-Pidancet who opened his personal archives to us and provided iconographic documents from Jacques Majorelle and his grandmother, Maïthé Majorelle, executor of the artist’s will, permitting us to discover the period photos of many unpublished pictures.

We thankthe grandchildren of Jacques and Andrée Majorelle, née Longueville, who permitted us to access their collections, most particularly François Chomel, son of Jika Majorelle, the artist’s daughter, representing his siblings, as well as Serge Majorelle, son of Jean-Louis Majorelle, the artist’s son, representing the other siblings.

We warmly thank the Fondation Jardin Majorelle which generously supported the book; Pierre Bergé, president, Madison Cox, vice-president, and Quito Fierro, secretary general.

We also thank:

The musée Yves Saint Laurent of Marrakech; Björn Dahlström, director, as well as Fatima Zahra Mokhtari, Kevin Kennel, Soraya Abid, Nadia Chinbo and Sanaa El Younsi.

The French embassy in Morocco; Mr Jean-François Girault, French ambassador.

The French general consulate in Marrakech; Mr Éric Gérard, general consul of France.

Lynne Thornton, who gave us access to the authenticity certificates established over the last fifteen years, Françoise Zafrani, for his rigorous approach to Jacques Majorelle’s works.

Acknowledgements

Michel Jullien, who did the page layout of this work with patience, efficiency and subtlety, with its 1,055 sheets of the pictures in the repertory.

Les Éditions Norma, Maïté Hudry and Matthieu Flory.

The Anglo-Saxon auction houses: Sotheby’s France, Cécile Verdier; Christie’s France, François de Ricqlès, Victoire Gineste, Gilles Chwat and Pierre-Emmanuel Martin-Vivier.

The Paris auction houses: Aguttes, Anne Jouannet and AnneMarie Roura; Artcurial, François Tajan, Olivier Berman, Hugo Brami and Stéphane Briolant, photographer; Baron-Ribeyre; Binoche & Giquello, Claire Richon; Claude Boisgirard and Pascal Faligot, photographer; Collin du Bocage; Cornette de Saint-Cyr, Charlotte de la Boulaye; Drouot-Estimations; Dumousset-Deburaux; Eve; Fauve Paris, Lucie-Eléonore Riveron and Cédric Mélado; Gros & Delettrez, Lilith Laborey and Antoine Saulnier; Christophe Joron-Derem and Gaëtan Ducloux; Massol; Millon, Anne-Sophie Joncoux Pilorget; PescheteauBadin, Brice Badin; Piasa, François Epin; Tajan, Déborah Teboul; Rossini, Quentin Breda; Vermot & associés, Nathalie Vermot.

The auction houses in the provinces: Anticthermal, Nancy, Sophie Teitgen; Laurent Bernard, Dreux; Hôtel des ventes de Monte-Carlo, Frank Baille; Étienne de Baecque and Géraldine d’Ouince, Lyon; Bertrand & Duflos, Nantes, Virginie Bertrand; Damien Leclere, Marseille; Rometti, Nice; Var Enchères, SaintRaphaël; Cortot-Vrégille-Bizouard, Dijon, Isabelle Mercier.

The auction houses and galleries in Morocco: CMOOA., Casablanca, Hicham Daoudi; Galerie 38, Casablanca, Khalil Saher.

The experts: Jean-Marcel Camard, Frederick Chanoit and Pauline Chanoit, Michel and Raphaël Maket, Jane Roberts,

and the galleries of Mathias Ary Jan, Didier Charraudeau, Alexis Pentcheff and Waring Hopkins, who also provided us with photographic documents.

The collectors: Daniel Anzel, Jean-François Appert, Annette BeckFriis, Pierre Bergé, Michèle Cahen, Fabrice & Rosy Chambon, Philippe Crespo, Bart de Block, Fabienne Fiacre, Olivier de Montal, Jean-François Cauchon, François Darmon, Guy Grardel, Emmanuel Journe, Patrice Lerat, Joseph Lorcy, Serge Lutens, Jacqueline Marnier-Lapostolle, Patrick Martin, Collection Bank Al-Maghrib, Luc Pignot, François Privat, Robert Rossi, Pierre Samon, Florence Serre, Jacques Simeray, Franck Stefani, Mohammed Tazi, Tamy Tazzi, Colette Zimeray and Mustapha Zine, as well as all those who wished to remain anonymous.

The museums that were kind enough to authorise us to reproduce the photographic documents of the works in their possession: Musée de l’École de Nancy, Valérie Thomas; Musée des Beauxarts de Nancy; Musée de Narbonne; Musée d’Orsay; the Stanislas municipal library in Nancy, Corinne Fournery. Michèle Maubeuge, who guided us in our research.

The Drouot auction house in Paris and its archives, Olivier Lange, Laurence Mille.

Luc Paris, photographer. Noëlle, Eléonore, Félix-Félix, Joséphine as well as Julien Vergès, who participated in the family research work during all these years as well as Juliette Caussil and Angèle Coulard.

Printed and bound in September 2017 by Re.Bus, Italy

Graphium, Saint-Ouen

Lithographs:

329-352.qxp 07/08/2017 13:31 Page352

Les Éditions Norma thanks ACR international.

1. Jacques Majorelle on holiday in the Loiret, L’Ortie villa in 1911.

2. Jacques Majorelle in 1907.

3. Jacques Majorelle with his mother on the terrace of the Jika villa in 1906.

4. Jacques Majorelle as a young schoolboy in Nancy, c. 1895.

5. An artist’s afternoon, c. 1904.

6. Jacques Majorelle in a tent in Egypt, c. 1914.

7. Jacques Majorelle in Paris in 1934.

1. Jacques Majorelle on holiday in the Loiret, L’Ortie villa in 1911.

2. Jacques Majorelle in 1907.

3. Jacques Majorelle with his mother on the terrace of the Jika villa in 1906.

4. Jacques Majorelle as a young schoolboy in Nancy, c. 1895.

5. An artist’s afternoon, c. 1904.

6. Jacques Majorelle in a tent in Egypt, c. 1914.

7. Jacques Majorelle in Paris in 1934.

Souk couvert, Marrakech, mixed media on paper, 53 x 63 cm, 1950.

Bakal et porte dans les souks, gouache on canvas, 50.7 x 63.5 cm, 1955–1960.

Right-hand page

Souk à Bâb Debar, oil on canvas, 45.8 x 55.5 cm, 1921.

Souk couvert, Marrakech, mixed media on paper, 53 x 63 cm, 1950.

Bakal et porte dans les souks, gouache on canvas, 50.7 x 63.5 cm, 1955–1960.

Right-hand page

Souk à Bâb Debar, oil on canvas, 45.8 x 55.5 cm, 1921.