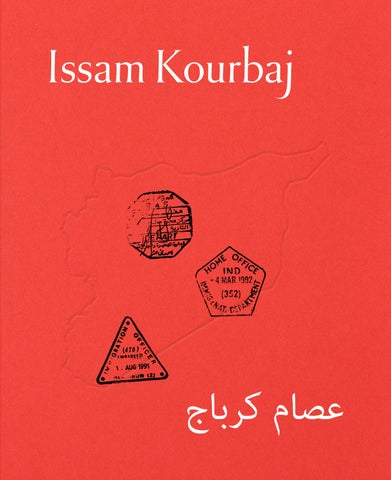

Issam Kourbaj

Andrew Nairne and Graham Virgo

Preface

Bonnie Greer

The Poetry of Objects: From Boy-Calligrapher to Experimental Artist

Rana Haddad

A floating archive

Brian Dillon

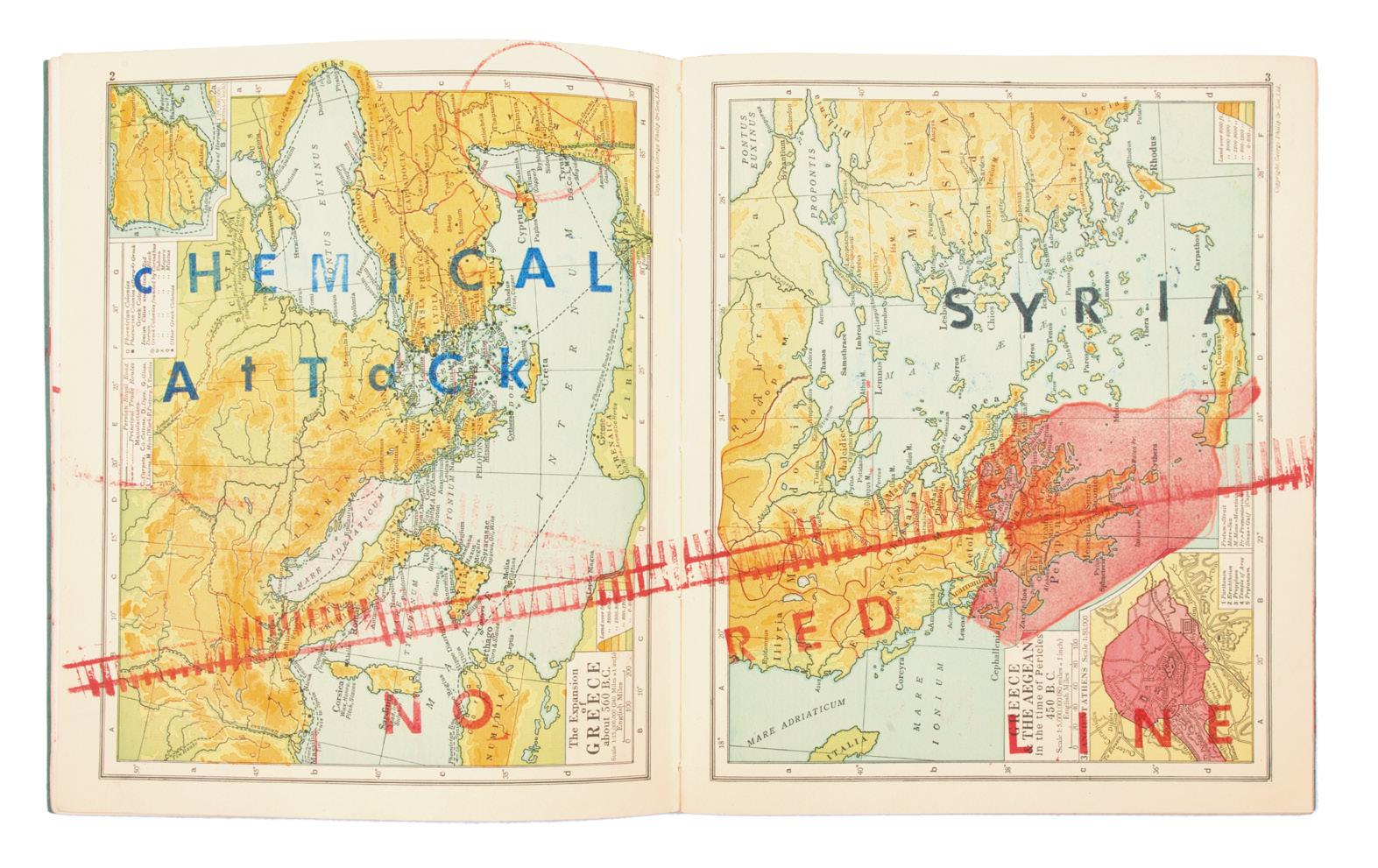

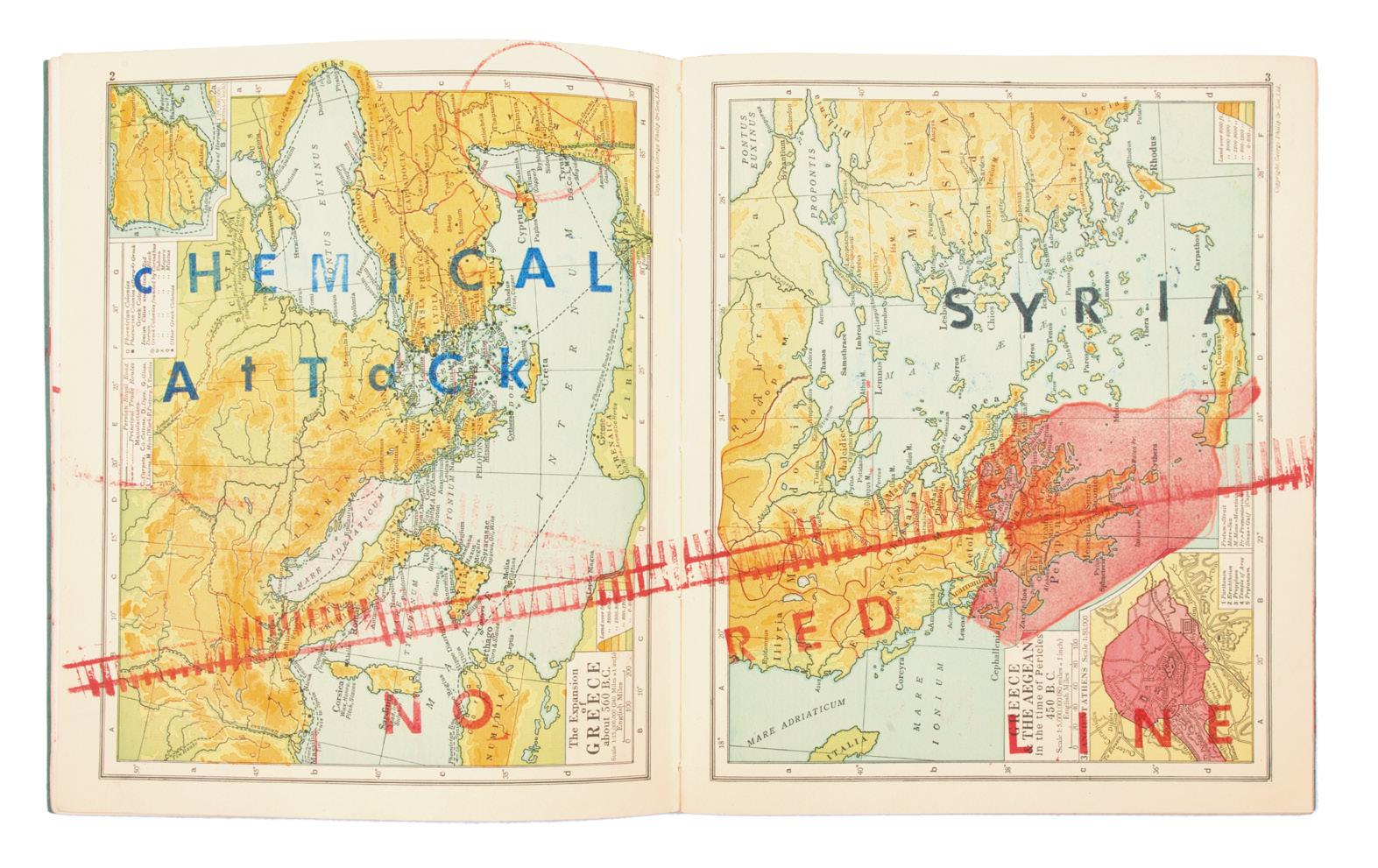

You are not you and home is not home

Prerona Prasad

View

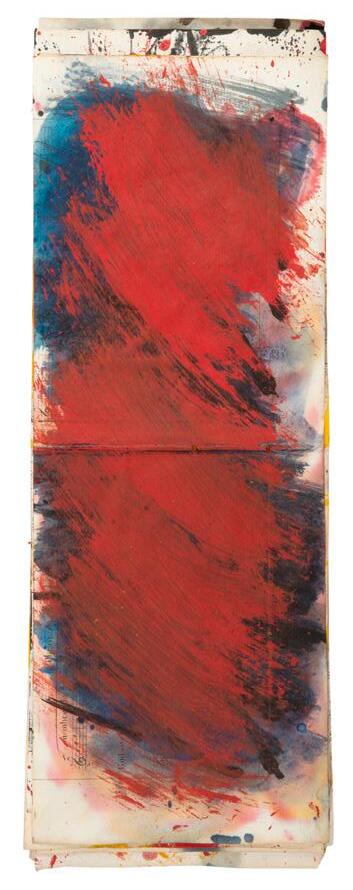

Preliminary sketch for Barbed Europe, Migrants’ shipwrecks, 2023-24

Studio view with seeds from ICARDA

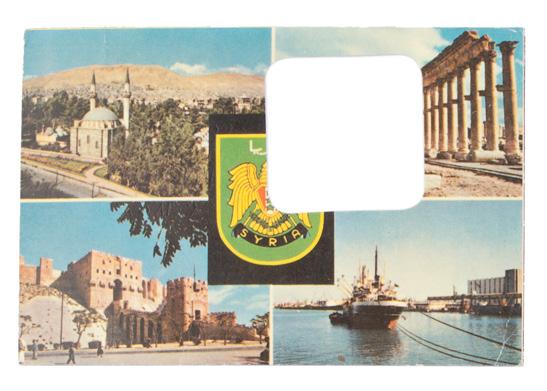

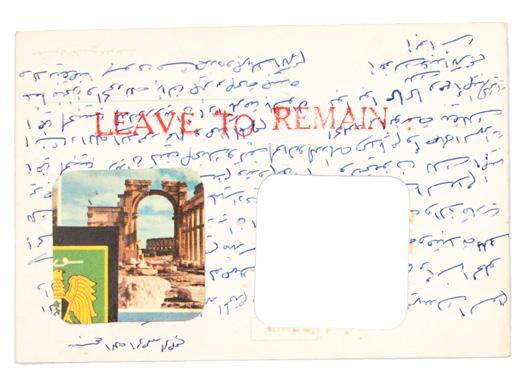

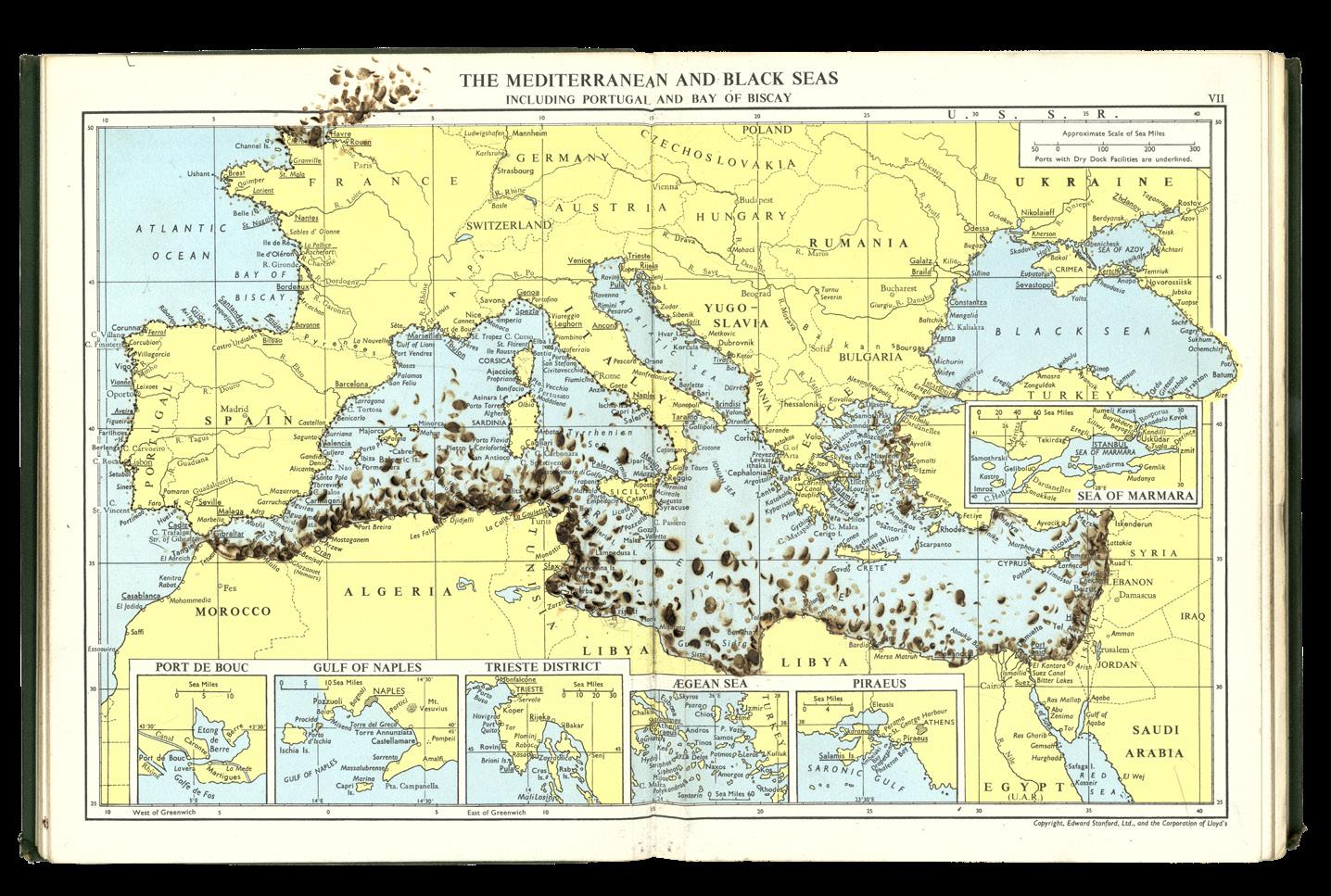

While words can travel on the backs of stamps, safe passage for people fleeing the destruction of their homes is far more elusive. In 2017, Kourbaj displayed the first iteration of Dark Water, Burning World, an installation of small boats made of bicycle mudguards with tightly packed matches standing within. Once assembled, the matches are set aflame, representing the damage done to bodies and psyches by forced displacement and the terror of flight. The burnt matches stand in for both the people and the trauma that they carry with them. Inured as we are to images of dangerously overcrowded boats, first in the Mediterranean and now in the Channel, we have accepted the absurdity of the fact that a journey between London and Damascus, that takes a mere five hours by air, can take months or years for a refugee.9

The pathos of the overcrowded boat has a long history in the visual culture of the British Isles. From the horror of the 1788 engraving of the conditions on the notorious slave ship Brooks to the melodrama of Ford Madox Brown’s The Last of England (1860), images of transport ships have played an important role in advocating against injustice. Today’s artists contend with an audience accustomed to the real thing: daily images of sinking boats and their precariously perched human cargo. Kourbaj’s visual strategy is not to overwhelm but to draw in. His boats are no more than an eyeful: a microcosm of an enormous tragedy. When Neil MacGregor, former director of the British Museum in London, selected Dark Water, Burning World for the 101st object in his series A History of the World in 100 Objects, he described the boats as possessing ‘great capacity to engage imaginative emotion with fragility, vulnerability, and despair’.10

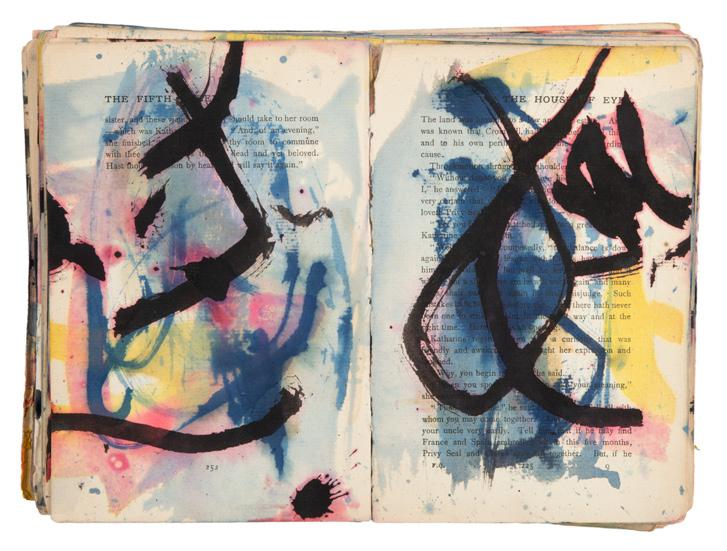

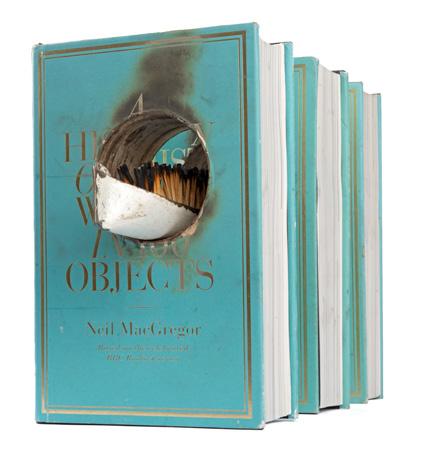

At the launch of his book, Dark Water, Burning World, at the British Museum in March 2023, Kourbaj unveiled a new work entitled Precarious Passage: a copy of MacGregor’s book of the series A History of the World in 100 Objects with a hole bored through it, in which Kourbaj placed one of his boats.11 As part of the exhibition at The Heong Gallery, Precarious Passage comprises 13 books, one for every year of the Syrian conflict. In Kourbaj’s words, ‘Precarious Passage describes the journey we are all making in a fragile boat across the unpredictable ocean of time.’12 A more sinister reading is that two million years of human development, exemplified by artefacts collected and preserved in one of the greatest cultural arks in the world, have led us directly into the closing maws of a humanitarian and climate Armageddon. The genteel turquoise and gold cover of MacGregor’s book is the calm surface, concealing the churning human flows within.

The final ‘boat piece’ in the exhibition was made in response to the UK Home Office’s decision to use the Bibby Stockholm, an ageing ‘accommodation barge’, to house over 500 adult male asylum seekers at Portland Port in Dorset.13 Kourbaj’s sculpture Keep them at bay features rusting, upturned sardine tins stacked tightly on a wooden base.14 This work directly addresses the British viewer, complicit in the everworsening standards of treatment afforded to asylum seekers. Packed like sardines,

at double the capacity for which the vessel was intended, the Bibby Stockholm recalls 19th-century prison hulks, made famous in the opening chapters of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations. 15 By cruel coincidence, the last British prison ship, HMP Weare, was a repurposed ship called Bibby Resolution, which held male prisoners in Portland Port until 2005. Keep them at bay also challenges the cruelty of housing asylum seekers on water, denying them the psychological comfort of reaching solid ground and, in some cases, reigniting the trauma of terrifying sea voyages.

Between the comfort of the familiar and the dread of the uncanny is the line traversed by artists of displacement. Before Kourbaj, Mona Hatoum used everyday materials of the home, such as kitchen utensils, soap, and furniture, with alterations in scale, texture, and spatial rearrangements, to create objects that oscillate between familiarity and terror.16 Born in Lebanon to Palestinian parents, Hatoum was forced into exile in London in 1975 by the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War. Hatoum’s response in art, much like her fellow Palestinian Edward Said’s in letters, has been to highlight the enduring placeless-ness of displacement that is experienced by refugees and exiles of diverse backgrounds: what Said terms the ‘perilous territory of not-belonging’.17 As part of both Cambridge exhibitions, Kourbaj has created new work using mattress frames and springs; for the works at the Heong Gallery, frames and springs were harvested from the students’ discarded mattresses at Downing College. Stripped of their padding, the mattresses take on menacing forms. Torn in two is akin to a two-sided barricade on either side of a window, preventing both looking out and looking in. The knots in the springs are cut out and hammered directly into the wall to create a barbed outline of Europe in Barbed Europe: Migrant Shipwrecks, where the Mediterranean Sea becomes a graveyard of stranded seeds.

From mattresses that you cannot sleep on to clocks that don’t tell the time, Kourbaj’s works on home and displacement create waves of surreal unease. In The dark side of the ‘unknown’ ray, Kourbaj reimagines an elegant 10th-century bowl made in Nishapur, Iran, which he encountered in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, as a wall-based work nearly three metres in diameter.18 The elongated ’alif-s and lām-s in the inscription make the bowl look like a sundial missing its gnomon. Kourbaj replaces the letters with cut-outs from anonymous x-rays of

Strike, March 2018. Documentation of performance at Kettle’s Yard