Unless the Lord builds the house, its builders labour in vain.

Psalm 127, verse 1

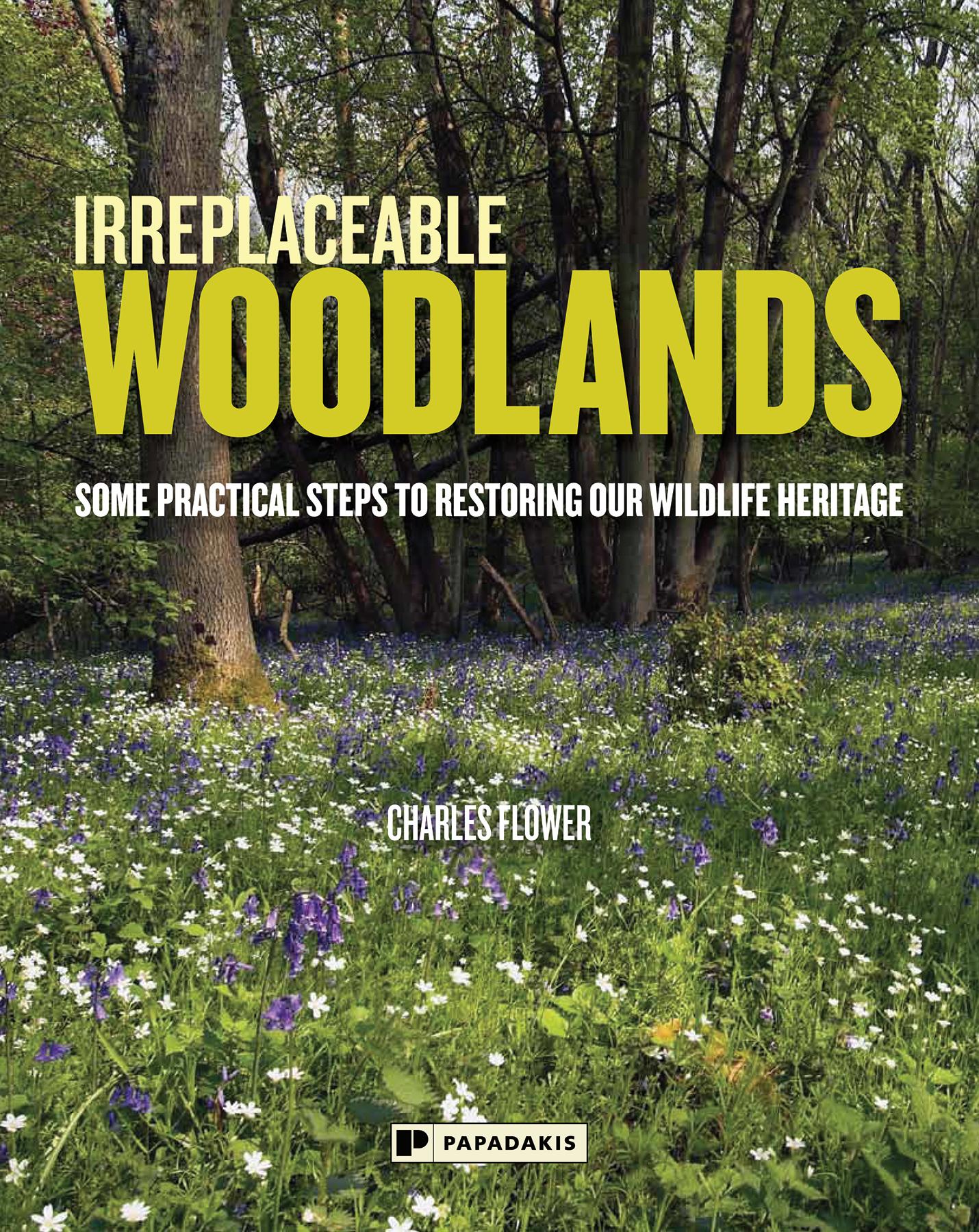

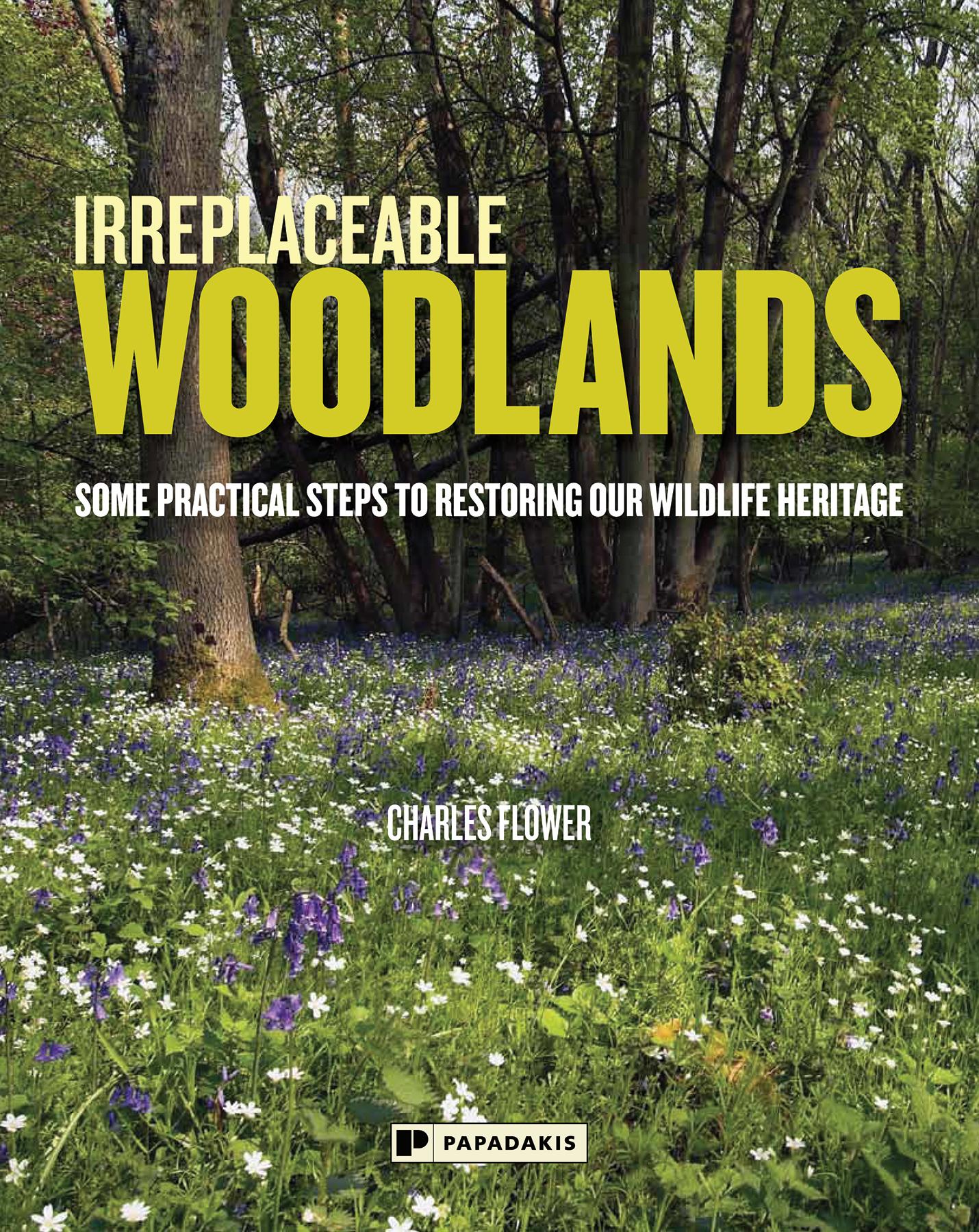

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Papadakis Publisher

An imprint of New Architecture Group Limited

Kimber Studio, Winterbourne, Berkshire, RG20 8AN, UK info@papadakis.net | www.papadakis.net

@papadakisbooks PapadakisPublisher

Publishing Director: Alexandra Papadakis

Design: Alexandra Papadakis & Aldo Sampieri

House Editor: Sheila de Vallée

Production: Dr Caroline Kuhtz

ISBN 978 1 906506 53 7

Copyright © 2014 Charles Flower & Papadakis Publisher.

All photographs unless stated below © 2014 Mike Bailey & Steve Williams

All rights reserved.

Charles Flower hereby asserts his moral right to be identified as author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Publisher.

A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in China

Photo Credits:

All photos © 2014 Mike Bailey and Steve Williams. All other photos © 2014 the following: Butterfly Conservation: p11 (btm right), p178 (top left), p179 (left second from top)

Peter Creed: p181 (6 photos)

Sue Eden: p200 (top left)

Charles Flower: p12, p19 (btm), p28, p32 (top right), p35 (btm left), p35 (btm left and right), pp42-43, p48 (top left), p52 (centre right), p63, p68 (left and right), p71 (top), p105 (btm), p139 (top, 2nd, third and btm row), p190 (top right), p203 (btm), p210 (left), p213(btm), p214 (right), p219 (right), p220 (top), p221, p229 (right), p231

The Museum of English Rural Life: p32 (left), p34 (top/btm), p36 (top/btm), p41 (top/btm)

We gratefully acknowledge the granting of permission to use these images. Every possible attempt has been made to identify all images and contact copyright holders. Any errors or omissions are inadvertent and will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Preface 8 1 INTRODUCTION 10 How to maintain the incredible diversity of an ancient woodland. 2 HISTORY OF MAPLEASH COPSE 16 The fascinating history of the copse managed by Charles Flower and an overview of the woodland clearance since Man’s earliest farming. 3 MEDIEVAL WOODLAND PRODUCTS 28 How the key species of oak, ash and hazel supplied the essentials of medieval rural life. 4 WOODLAND TREES & SHRUBS 44 The most important species of trees and shrubs, their characteristics and dispersal strategies. 5 RESTORING DERELICT HAZEL 78 A detailed account of the techniques required to restore a derelict hazel copse with all the trials and tribulations of outwitting deer and rabbits. 6 DECAYED WOOD & FUNGI 90 The vitally important role of dead wood, standing and fallen, with descriptions of some of the extraordinary fungi which help convert dead wood into woodland soil. 7 WILD FLOWERS OF THE WOOD 114 A detailed account of the wild flowers, 90 per cent of which depend on rides and glades for their survival, and the effects of coppicing on the ground flora. 8 FERNS, MOSSES, LIVERWORTS & LICHENS 142 The amazing world of ferns, mosses and lichens and how to encourage these often over-looked organisms. 9 INSECTS & SPIDERS 164 A photographic glimpse of the fascinating insects that inhabit ancient woodland and their specialised requirements. 10 OTHER OCCUPANTS OF THE WOOD 188 The rich diversity of animal life in an ancient woodland, much of which is nocturnal, from birds to dormice and badgers, and the clues to its presence. 11 MANAGING A WOOD FOR DIVERSITY 208 Nine practical steps to safeguarding the diversity of the woodland including the detailed management of rides and glades. 12 ESTABLISHING WILD FLOWERS IN WOODLAND & GARDENS 226 How to encourage wild flowers in new broad-leaved woodland when shade levels develop. Postscript 236 Acknowledgments 236 Bibliography 237 Index 238

CONTENTS

History of MapleasH Copse 2

an ordInary Wood

Mapleash Copse is in one sense a very ordinary wood. It is described as “ancient” woodland, meaning that there has been woodland on the site since 1600. It has probably been there for much longer. It was designated as an SSSI (Site of Special Scientific interest) but this only happened because the adjoining area of heathland, Snelsmore Common, was also an SSSI and Mapleash Copse was somehow included because my father-in-law’s activities in reviving the hazel were considered unusual at the time. There is nothing particularly notable about the wood’s flora and fauna; however, there is no doubt that because part of the wood is being actively managed for high quality hazel, the effect on the ground flora and associated wildlife is somewhat different from an unmanaged wood.

descrIptIon/geology of the Wood

The wood lies on the east side of the Winterbourne valley just above the village of Winterbourne, measuring approximately 600m from north to south and 200m from east to west. The valley extends from the M4 to the north and then south to the village of Bagnor. Much of the upper slopes of the valley are steep, wet, and impossible

to farm, which is probably why the wood is here today. Most woodland on reasonable farmland has been cleared for arable crops. The wood is also geologically rather interesting because of events after the last Ice Age.

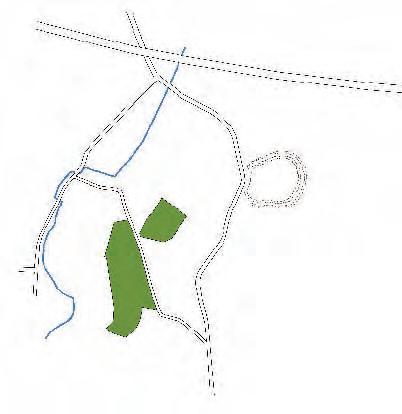

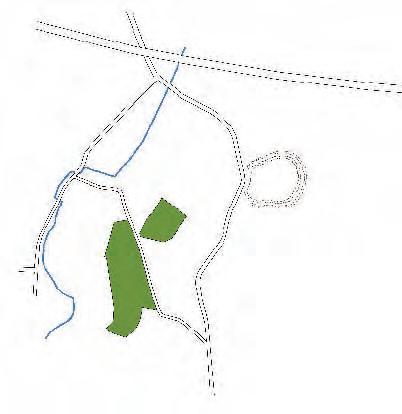

Mapleash Copse – Location (below) and Principal features (above)

Wantage

Boxford

Winterbourne Village

M4

Mapleash Copse Winterbourne Pebble Lane Stream

Bussock

Camp Vauxhall

Copse

Newbury

opposite: Cherry leaves turn the wood scarlet in autumn

17 Wych elms Hazel coppice Hazel coppice Hazel coppice Hazel coppice Beech plantation Ponds Hazel coppice Hazel coppice Hazel coppice Willow pollard Larch plantation Douglas firs Ancient field maple Smallleaved lime Grey poplar Twisted thorn Veteran beech Veteran field maple Ash stools Veteran ash Sycamore stool Bees’ nest Ash stool Veteran ash Middle Path (north) TopPath TopPath MiddlePath (centre) Ancient Path Lime Path Path Church MiddlePath(south)

34 Irreplaceable Woodlands

similar number of bindings. In the winter months, the agricultural labour force would spend most of its time hedging and ditching and all the hedges on a farm would be cut and laid in rotation.

But there was another product arguably even more important than all of these, the thatching spar. Two foot (0.6m) long and cleft into four from a green rod not more than 2in (5cm) in diameter, these spars were pointed at both ends and when used were bent like a giant hairpin and thrust through the protective thatch. This thatch weather-proofed the cornricks until they were opened up and the sheaves taken into the barns and threshed between the open doors so that the wind could blow away the chaff. In the nineteenth century the threshing machines, still to be seen today at agricultural shows, replaced hand threshing. Hayricks were thatched in the same way. Thomas Hardy in his book The Woodlanders has left a fascinating account of this trade as carried on in West Dorset in the latter half of the nineteenth century, where the rate paid for making thatching spars was 18p per thousand. Cottages and farm buildings were, of course, thatched as well but only every 20-30 years. Thatching a medium-sized cottage would require over 10,000 thatching spars.

A by-product of this hazel work was the bundles of brushwood or faggots. These were in great demand by the village bakers for a quick blaze. A local man who died about ten years ago recounts an episode in Oare in Wiltshire where he was brought up. He was travelling on top of a wagon loaded with bundles of faggots. One of the ladders broke when going up a steep hill and he and an avalanche of fagots rolled off the back of the wagon. There was always demand for pea sticks and bean rods. There were no cheap canes from China in those days.

ash products

Life in medieval times revolved around farming and ash was the key wood for hand tools. Although not at all durable in the ground, it is easily cleft and its toughness and flexibility is without equal. Cleft wood is stronger than sawn wood because the cleaving, splitting or riving parts the wood fibres along their length, resulting in fewer points of weakness with very few fibres being torn. The ash worker and the blacksmith were key partners in every village. Longer ash poles were used for shepherds’ crooks, hoes, pitchforks, rakes and scythes. Ash steams well and maintains its shape so the scythe handle was made from steamed ash. For the shorter, stouter tool handles, the preferred

MedIeval Woodland products 35

opposite top: Reaper and binder at work with flattened crop being scythed opposite bottom: Straw from the corn crop was vital to thatch all the ricks

below left: Thatching spears ready for use

below right: A thatching spear bent like a hairpin securing the top of the thatch

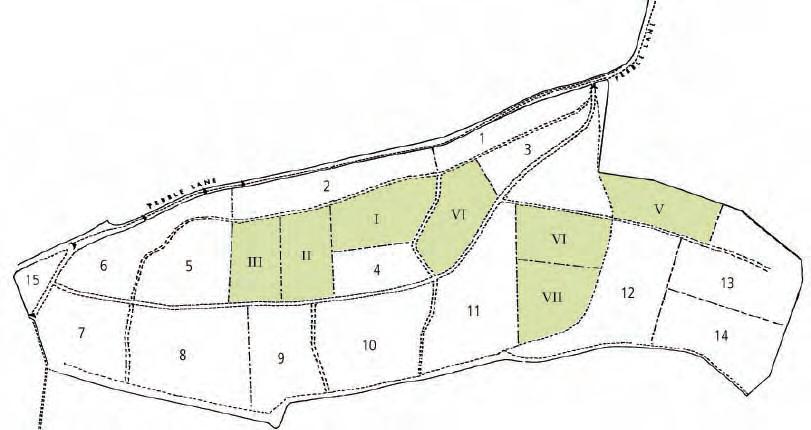

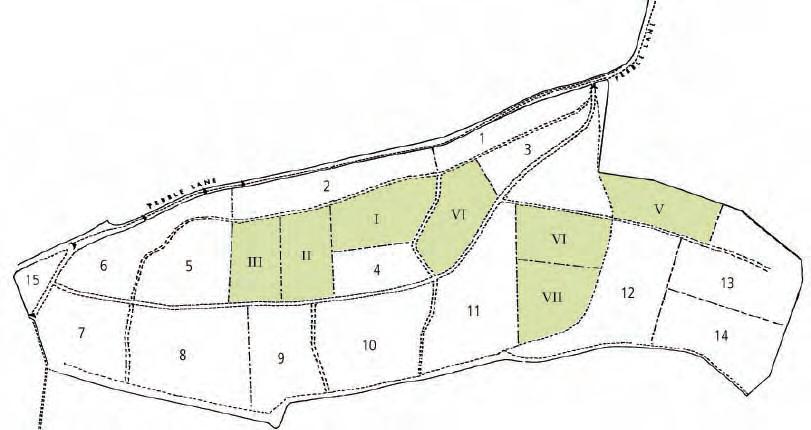

Mapleash Copse

Hazel coppice I-VII

Other compartments 1-15

Woodland compartments

These percentages say it all. Only 4% of the oaks have been planted in the last 50 years and only 20% in the last 80 years. If we were growing oak up to a harvesting age of 150 years old, 50% of today’s trees should be around 75 years old instead of 100 years old so we have

some catching up to do. One of the reasons that there are no young oak in the wood is that the canopy is closed and oak seedlings are very light demanding and will only grow in clearings. Where there are open areas such as rides and glades, we don’t want oak trees!

%

Summary of oaks: 4% less than 50 years old, 44% between 50 and 80 years old, and 52% over 100 years old.

48 Irreplaceable Woodlands

above left: Even age structure revealing lack of management above right: Heavy grazing in a neighbouring wood

Inches 20-40 40-60 60-80 80-100 100-120 over 120 cm 50-100 100-150 150-200 200-250 250-300 over 300 approx age 25-50 50-80 80-100 100-130 130-160 over 160

oak survey – Mapleash copse

Girth

16 28 36 12 4

4

–

I have listed the trees which we have in the wood, followed by the shrubs. The compartments shown in the diagram opposite are used to indicate the location of individual or groups of trees.

principal trees in Mapleash copse and insects associated with them:

Ash (68) Beech (98)

Birch (334) Cherry (157)

Common lime (57) Crab apple (118)

Field maple (51) Grey poplar

Oak (423) Scots pine (172)

Sweet chestnut (11) Sycamore (43)

Crack willow (450) Goat willow

Wych elm

Trees introduced recently:

Alder (141) Hornbeam (51)

Rowan (56) Small-leaved lime (57)

Yew (6) Conifers

Note: The figures in brackets after each tree indicate the number of insects associated with that tree species. More recently introduced species such as sweet chestnut have many fewer insects associated with them as compared with, for example, oak or willow which have over 400 each. Birch scores over 300. Birch and willow would not usually feature in a forestry planting scheme, but they are so valuable for insects that they need to be incorporated in a small way. This is why we leave the occasional birch in our coppice plots as well as goat willow, even though we may have to prune the goat willow half way through the coppice cycle.

I have made a distinction between those species which have been in the wood for many years and those which have arrived recently or have been introduced. Without records, we have no idea whether additional species were formerly present in the wood.

pollInaTIon and dIspersal

Considering the importance of the seed of our native trees, it is remarkable how little most of us know about it. The problem is that many of the flowers are tiny, high up on the tree and consequently very hard to see. For example, the flowers of wych elm are about a quarter of an inch in diameter (6mm).

A number of our common trees as well as hazel are wind pollinated using catkins or other flowers, which avoids the erratic behaviour of insects. Very large amounts of pollen are produced by ash, oak and elm as well as birch, beech and pine. All conifers are wind pollinated. The rather straggly catkins of the oak open in May. The female flowers which are destined to produce the acorns, are clustered at the tips of the shoots. Nearly all the wind pollinated trees flower early in the year when there are few insects active. This is also the time of year when there are no leaves on the trees and the flowers are freely exposed to disperse and receive pollen. However, some trees are also insect-pollinated such as the willows and sweet chestnut, with their catkins being freely visited in fine weather. Trees which are almost entirely insectpollinated include cherry, crab apple and rowan. The small flowers of the rowan are packed together to act as a convenient landing platform for the insects.

Trees manage their seed dispersal in a number of ways. Birch has the lightest seeds so wind is the key agent here. Ash, field maple, sycamore, willow and wych elm also rely on wind. Beech seeds or “mast” are eaten by pigeon and mice as are acorns, but the jay plays a special role in oak dispersal. The thrush family spread crab apples, cherries and rowan fruits.

Month showing peak pollen grains

Mar apr May June July

Hazel Willow Oak - Lime

Elm Ash Beech - -

Yew Birch Sycamore -Alder - Pine - -

Woodland Trees & shrubs 49

Wild privet

There are a few plants along the edge of the wood, which adds to our shrub diversity. It has very good nectar attracting many insects and it is the food plant of the privet hawk moth.

dog rose

This is a very beautiful plant which will climb through other shrubs to a great height but you don’t want to get too close to its vicious thorns.

spindle

The purists do not consider this to be a native shrub, but it has been here for at least 400 years and probably longer. The nectar is excellent attracting hoverflies and bees and the flowers are composed of striking pink four-lobed capsules. There is a large clump in Coppice Compt VI.

spurge laurel

This is one of my favourite shrubs. It is a discreet evergreen bush only about a metre high with scented flowers which are out in February. I suspect its wildlife value is very high. It grows particularly well either side of the Church path.

Traveller’s joy

This occurs mostly along the western edge where the chalk surfaces. It is a most vigorous climber and can smother smaller shrubs. It provides good habitat for birds but, as with all diversity arguments, you don’t want too much of it.

Wayfaring tree

The name of this shrub is curious. It rarely grows taller than 13ft (4m) so it cannot be called a tree. Why is it called wayfaring? As Richard Mabey remarks in his Flora Britannica, it is no more of a wayside speciality than a dozen other common species. Although it occurs in the wood, it never really flowers and is definitely at its best along tracks. The flowers are superb for all manner of insects and the fruits attract thrushes.

left: Ivy is an immensely powerful plant opposite: Dog rose

76 Irreplaceable Woodlands

their more rapid breakdown but, unlike oak, they are not nearly so durable and decay faster. It is all incredibly well organised.

Elton recognised 4 main types of decayed wood and I have added a fifth, fallen trees:

• standing decayed wood

• fallen trees

• boles after the tops have broken off

• logs of various sizes

• residual stumps, including roots

1. standing decayed wood

There are more oak in the wood than all the other species put together. With the various oak diseases now prevalent, there are many oaks with stag heads and a number that are dead, so the decayed wood supply has increased hugely in the last five years. The unique feature of oak is that dieback and death all take so long that decayed wood is not going to suddenly disappear. However, if oaks are

92 Irreplaceable Woodlands

above: Details of decay right: Standing decayed wood

scarce, there will be less standing decayed wood because the other species decay much faster. Standing decayed wood is of great importance for nesting birds such as woodpeckers, nuthatch, tree creeper and many of the tit family which nest in tree cavities.

2. fallen trees

Several substantial trees have succumbed to the prevailing wind in the lower part of the wood where they are more exposed. There are three oak and two cherry which are just as they fell many years ago.

decayed Wood & fungI 93

top: Fallen oak at the top of the wood above left: Cherry bark. The cherry in the photo appears to be decaying within the bark, with the bark being more resistant to decay above right: Detail of rotted roots and fungal growth that resulted in the tree being blown over

top row from left: Velvet shank, stinkhorn, fly agaric centre row: Yellow brain, turkey tail, common puffball bottom row: Shaggy scalycap, jelly ear, horn of plenty

top row from left: Velvet shank, stinkhorn, fly agaric centre row: Yellow brain, turkey tail, common puffball bottom row: Shaggy scalycap, jelly ear, horn of plenty

decayed Wood & fungI 111

top row from left: Southern bracket, jelly rot, blushing bracket centre row: Lilac bonnet, razorstrop fungus, trooping funnel bottom row: Oak mazegill, Boletus luridiformis

Ferns, Mosses, LiverworTs & Lichens 8

These are the woodland plants which are really off the radar. It is not easy to distinguish many of the ferns, the mosses are more difficult, and the liverworts are harder still. Ferns, mosses and liverworts reproduce by spores rather than by seed. Ferns have their spores on the underside of the fronds. Mosses have a simpler structure in that they produce spores in capsules which are released when the lid of the capsule falls off. Spores need wet surfaces to survive so damp woodland conditions are very helpful.

Lichens consist of a fungus which grows in close association, called symbiosis, with an alga. Reproduction is not by spores but by vegetative means whereby special structures drop off and form new plants. Much remains to be discovered as to how all this works in detail. The main constraint with lichens is air quality. If you examine gravestones in the London cemeteries, you can often date the dead lichens from when atmospheric pollution began to build up in the mid to late twentieth century. Sulphur dioxide which was produced by coal-burning industry and power stations then dissolved in water vapour to fall as acid rain. This wiped out most of the lichens in city centres and industrial areas.

I shall discuss ferns first, because of the fifty or so that are found in the United Kingdom only five occur in the wood. One of these is bracken (Pteridium aquilinum), a plant of considerable significance.

Ferns

Although general characteristics such as habitat and leaf shape are usually sufficient to identify a fern, there are a number of species where the sori have to be examined. These are the structures on the underside

of the fronds which are spore-producing sacs and which have a distinct shape and structure making identification certain.

Male fern (Dryopteris filix-mas) is probably the commonest British fern. It has a shuttlecock habit that is easily recognised and is widespread in the wood.

lady fern (Athyrium filix-femina) is less common than the male fern and prefers moister ground. The scaly stem and feathery appearance mark it out from the male fern.

scaly male fern (Dryopteris pseudomas) is a fine fern when fully mature; with its vigorous growth, large size, density and bright orange scales on the stem it cannot really be missed.

above: A rotten stump makes a perfect habitat for this lady fern

opposite: Scaly male fern – much the most handsome fern in the wood

143

more. Queen wasps (Vespula vulgaris) are to be seen on the bramble flowers; the photograph above shows how much larger it is than the hoverfly feeding beside it. Hornets (Vespa crabro) usually nest in the wood; one year they used an old greater spotted woodpecker’s hole. The hornet in the photograph above is expertly cutting free a bumblebee caught in a spider’s web to provide it with a free supper. Wasps and hornets use the well-known black and yellow coloration to warn off other species, especially birds. Two species of bumblebee are featured. Bombus vestalis is one of the earliest to appear, with queens searching for nests as early as February. They sometimes just collapse from exhaustion, and after five to ten minutes come back to life and fly off with renewed vigour. The other is Bombus lucorum

beetles

The star turn here is the cardinal beetle ( Pyrochroa serraticornis ), which is a highly noticeable scarlet and makes no effort to hide itself, so it must be extremely distasteful to birds and other predators.

172 Irreplaceable Woodlands

top row from left: Wild honey bee, queen wasp, hornet below right: Vestal cuckoo bumblebee (Bombus vestalis) having a rest opposite: Bumblebee (Bombus lucorum)

top left: Mouse store cupboard top and above: Details of mouse store cupboard left: Evidence of bats using green woodpecker’s hole opposite: Wood mouse

dormouse (Muscardinus avellanarius), 3in (8cm). I was always led to believe that they were rather rare. Then I read Sue Eden’s book Living with Dormice, which suggests that they really are not that rare but are just sensible in that they keep out of our way. So when I was topping the brambles in the wood in October 2010 and missed a dormouse winter nest by a couple of feet, I was not too surprised. The inside was beautifully lined with the seed heads from a nearby clump of great willow herb. The following autumn we found another nest in the garden, so they are about.

The next two mammals are the mole (Talpa europaea), 5.5in (14cm) and the hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus), 9in (22cm). The mole is believed to have three periods of rest and three of activity through a 24-hour period. When it is active, it patrols its burrows and eats any earthworms or insects that have fallen into them.

other occupants of the Wood 199

just when it is really getting away at fifteen years. This has made growing some species such as beech and oak almost impossible. Grey squirrels also do great damage to birds, raiding their nests and eating their young or eggs. However, something rather interesting is beginning to happen with the red/grey issue. There was a danger that the native red might die out all together, so trapping of the greys was stepped up in areas where the red was hanging on. This has been so successful that a significant number of people have got behind saving the red and getting rid of the grey. Given the fact that the grey is such a serious forestry pest, I would not be surprised if the grey was ultimately removed.

Continuing up the size scale we come to rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), which help to feed both stoats (Mustela erminea) and to lesser extent weasels

(Mustela nivalis) Rabbit numbers can fluctuate rapidly, which is why our coppice plots now have rabbit wire as well as deer fence to protect them. When ash branches are cut in the winter months, they are quickly gnawed by rabbits and tracks in a fall of snow are another reminder of how many there are about. I learnt from Mike Bailey, one of our photographers, a curious fact about rabbit droppings. Mike was brought up on a farm and knows all about country life. I asked him why rabbits seem to leave their droppings on stumps or other elevated sites. Was it the view? Not a bit, said Mike. When food gets really short in winter, rabbits will eat their droppings again, because on the first time through their gut, they are unable to remove all the goodness, so that pile of droppings on a stump is in fact a food reserve.

202 Irreplaceable Woodlands

Fox

Stoats and weasels are at the top of the food chain with the two heavyweights, fox (Vulpes vulpes) and badger. Foxes are controlled to a certain extent in our parish because of local pheasant shoots. Foxes have been known to make their earths in the sandy strata in the wood, but we are reasonably tolerant of them since we no longer keep chickens. A fox killed all 24 of our chickens on a July evening twenty years ago. The point is that there is some control. It is often thanks to the blackbird that we know what is going on. I was up listening to the dawn chorus one February (the time to hear this is, of course, in May but it means getting up much earlier!) and first to sing was robin, followed by great tit, blackbird and song thrush. Then I heard a furious alarm call from a blackbird to my left, a pheasant flying off in a hurry, and then more blackbird scolding as the fox

other occupants of the Wood 203

above: Muntjac

below: Badger hole

top row from left: Velvet shank, stinkhorn, fly agaric centre row: Yellow brain, turkey tail, common puffball bottom row: Shaggy scalycap, jelly ear, horn of plenty

top row from left: Velvet shank, stinkhorn, fly agaric centre row: Yellow brain, turkey tail, common puffball bottom row: Shaggy scalycap, jelly ear, horn of plenty