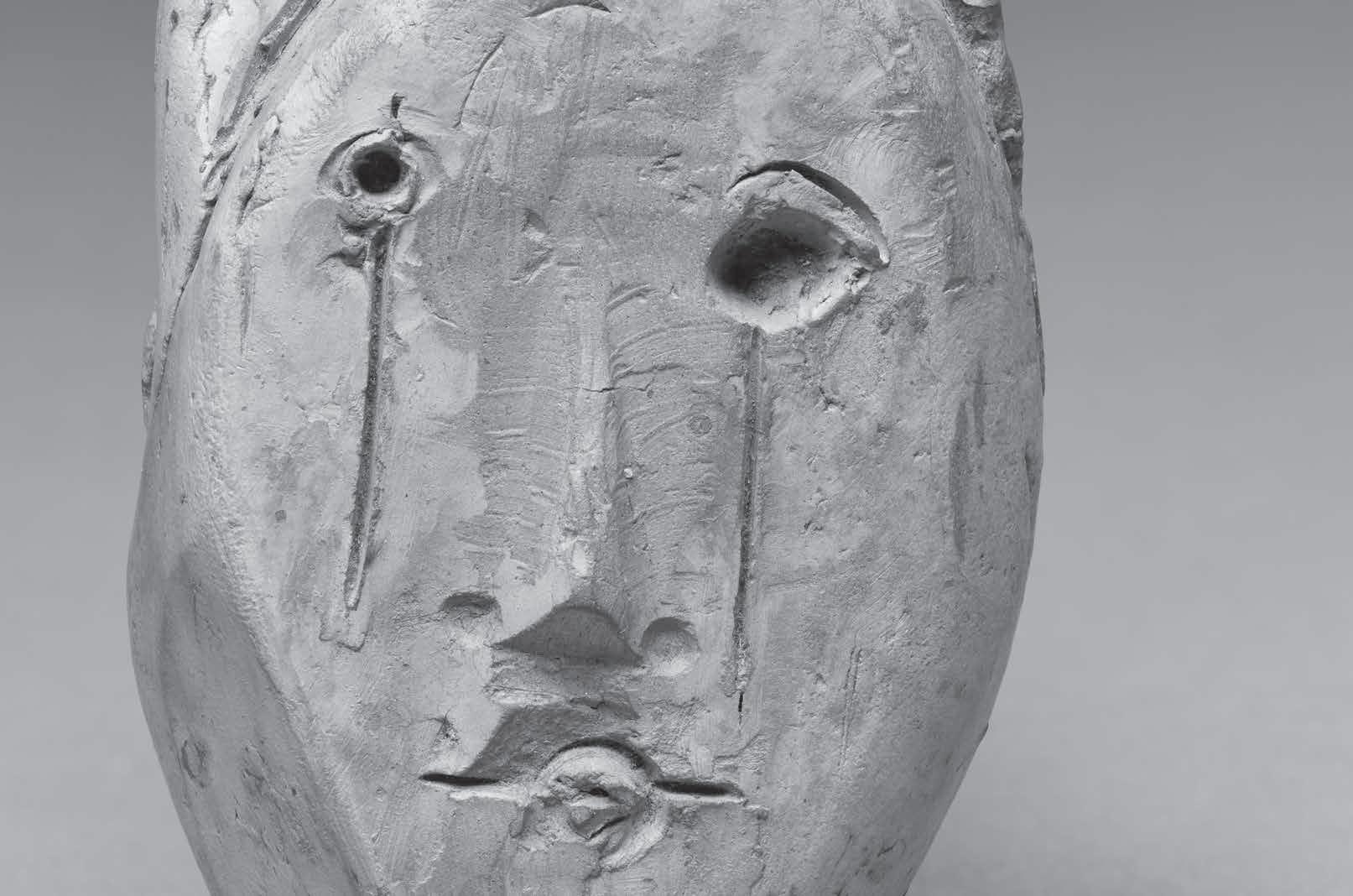

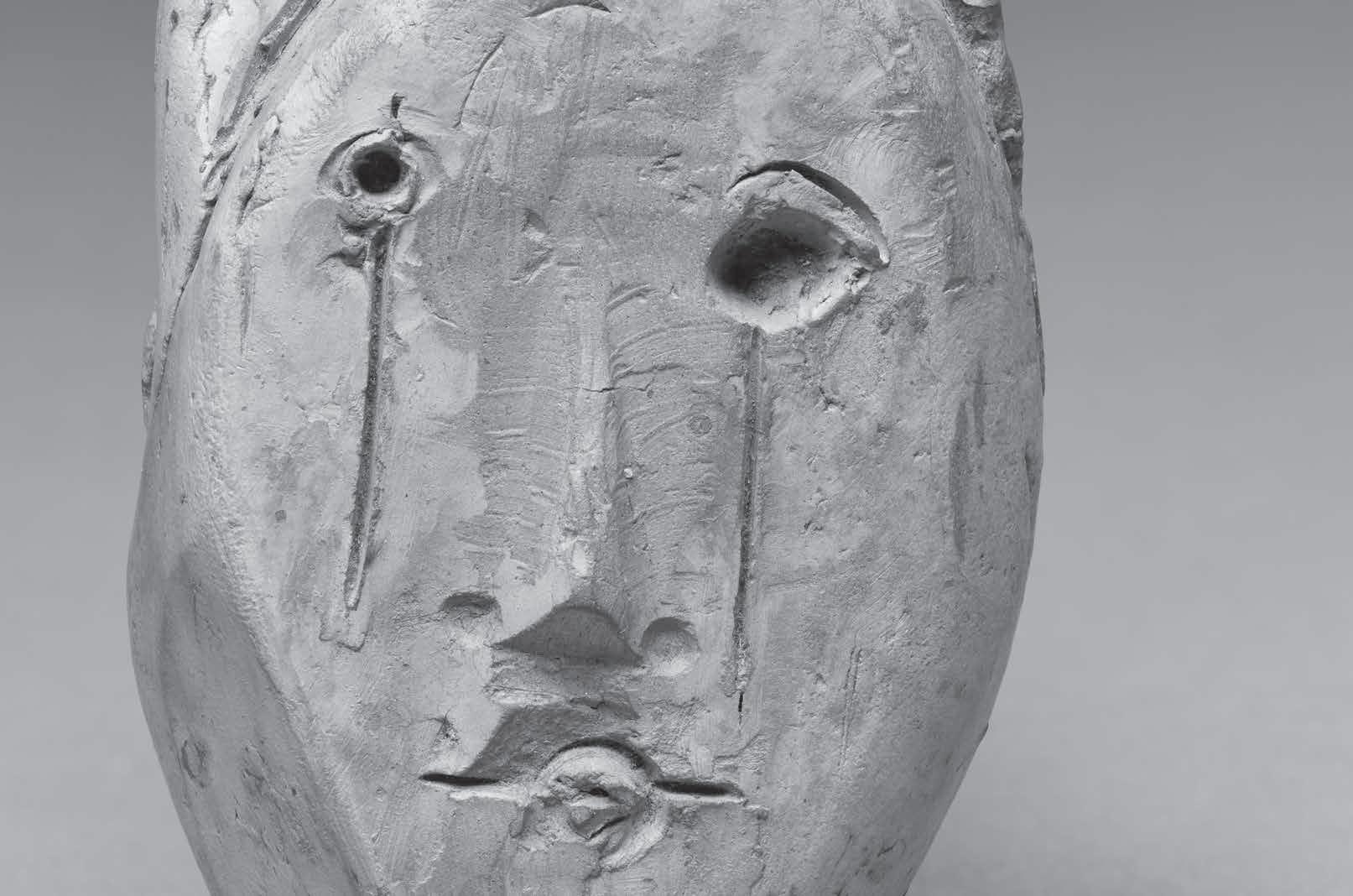

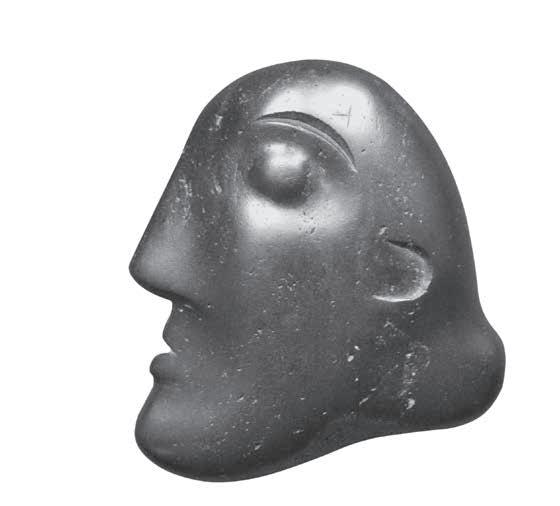

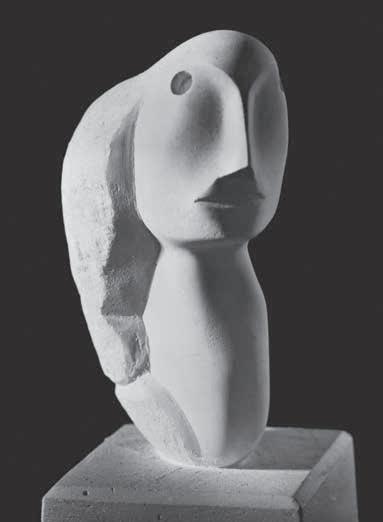

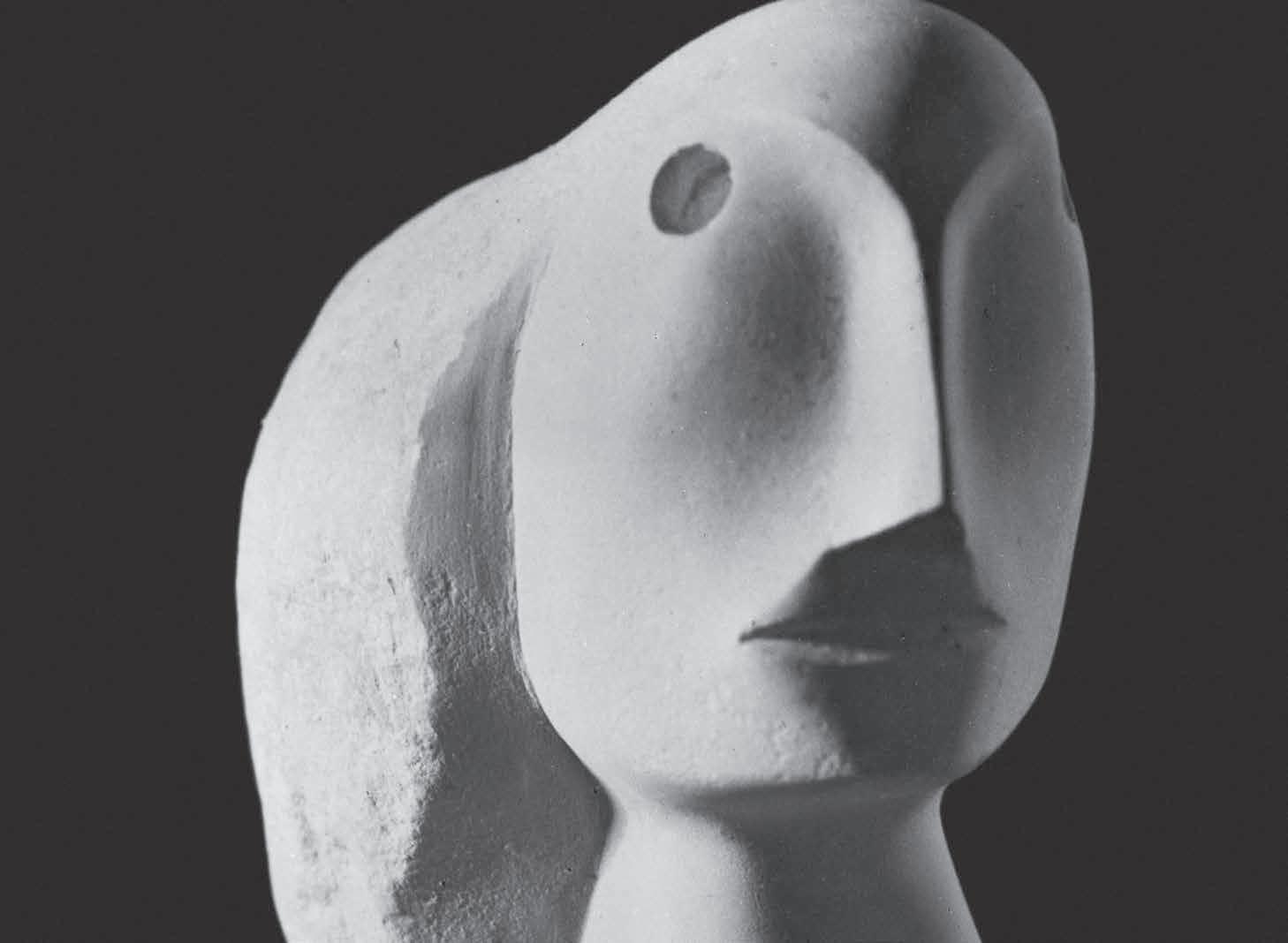

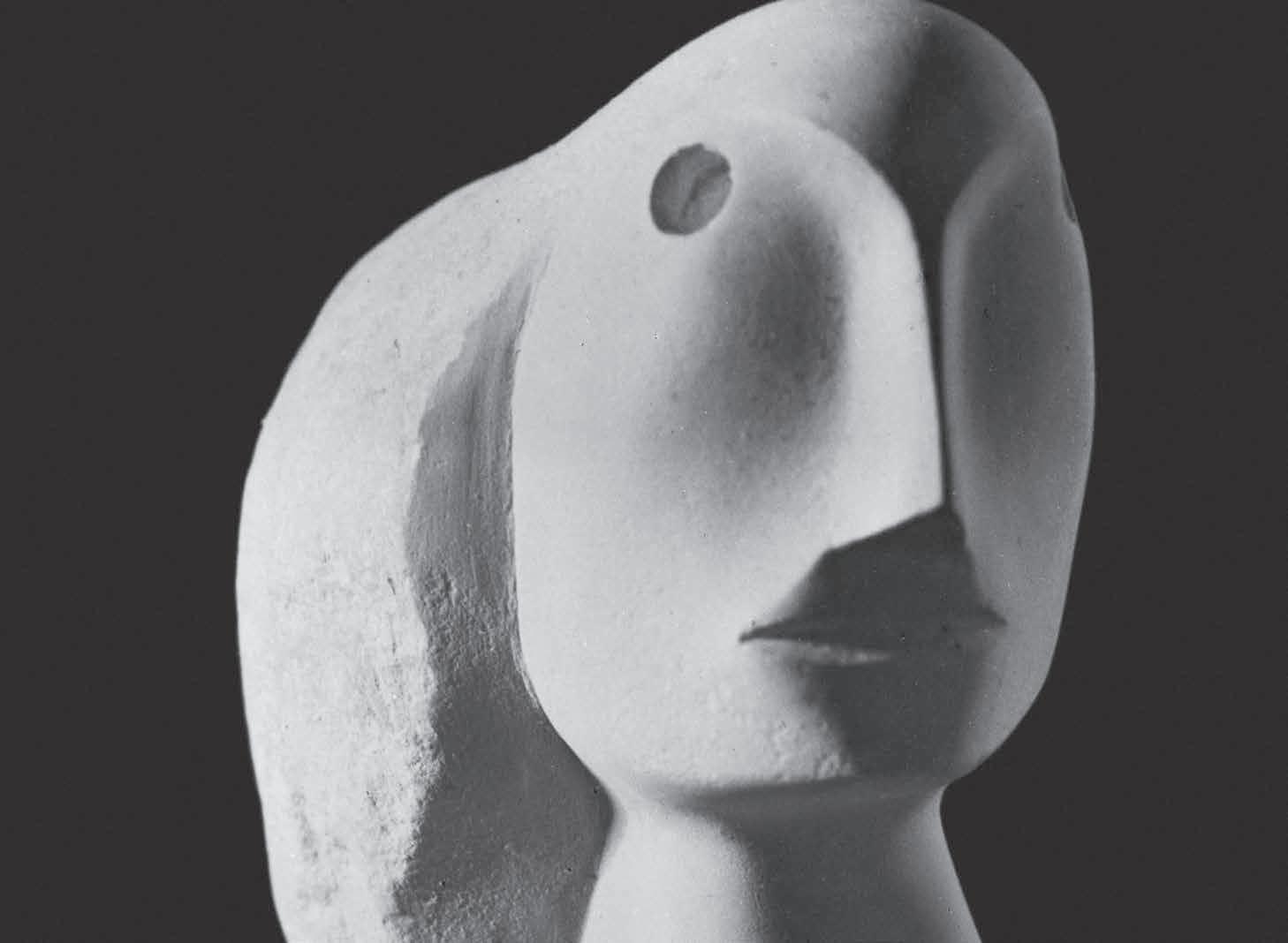

Detail of Small Head No. 8, 1953 (LH X62), p. 68

introduction p. 7 sculptures p. 16 works exhibited p. 92 chronology p. 95 acknowledgments p. 96

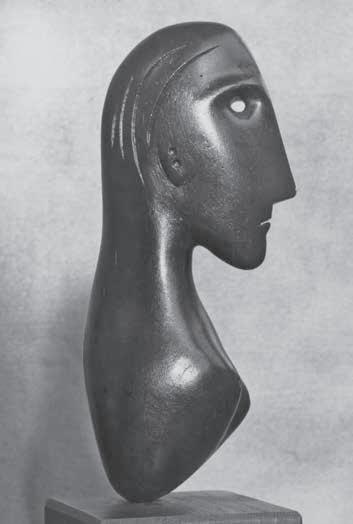

Group of heads and other sculpture in Henry Moore’s studio, c. 1953

Group of heads and other sculpture in Henry Moore’s studio, c. 1953

IN1954 Henry Moore’s great friend, the critic and poet Herbert Read (1893–1968), delivered the Mellon Lectures in Washington, DC, entitled The Art of Sculpture, and explained that his purpose was to establish ‘an aesthetic of the art of sculpture’. The lack of clear, autonomous laws had, he argued, allowed sculpture to be denigrated by many artists and generally to have been subject to the rules of other arts, painting and architecture. Read’s first chapter was ‘The Monument and the Amulet’, referring to the two forms from which an independent sculpture had gradually emerged. Tellingly, while one might refer to a grand figure or to architecture, from which the art of sculpture had to free itself, the other, the amulet, was a ‘small, portable charm, worn on the person as a protection against evil, or as an assurance of fertility’. The independent sculpture of the modern period, established by the likes of Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) and Henry Moore (1898–1986), existed, for Read,

‘somewhere between these two extremes – as a method of creating an object with the independence of the amulet and the effect of the monument’.1 Undoubtedly, Read’s close proximity to Moore will have shaped that understanding of the art of sculpture, its roots and its purpose.

Froman early date, Moore was associated with public monuments. He carved the figure of the West Wind on London Underground’s headquarters, 55 Broadway, Westminster, in 1928–9. After the Second World War, he secured an international reputation as the leading sculptor of his age and one whose largest works came to populate many of the great cities of the west – London, New York, Chicago, Dallas, Paris, Berlin, Toronto – and occasionally beyond. His fusion of the human figure with a form of nature-derived abstraction came, it seemed, to express the humanitarian, liberal values of a world recovering from the

war and its associated horrors. At the same time, from his earliest works to the end of his life, Moore produced objects that were small and intimate. At the beginning these were mostly carvings, and their size was, perhaps, determined by the material as much as anything. However, even later when his output was predominantly in bronze, the works began on a small, hand-held scale and, indeed, even those great metropolitan monuments started out as small maquettes. Moore’s art was one of intimacy and touch as well as one of monumentality and vision.

A key work in this regard is a small Head (ill. right and opposite) that belonged to Moore’s friend and patron, Kenneth Clark (1903–1983). It is one of several such heads carved from ironstone around 1930. Unlike the others, it does not stand up – as if made for exhibition – but is designed to rest in the palm of the hand. Retaining the feeling of the pebble from which it was carved, every part of its outer edge is curving, ensuring it could only ever lie, not stand, or be held between two fingers. It is impossible to see both of its contrasting faces at once, though both could be felt through touch. Anticipating Read’s lecture by over twenty years, Moore had made a modern amulet, a symbolic image that can only be experienced through the hand.

Read’s argument that monumental sculpture

Head (recto), 1930 (LH 87a) ironstone, height: 7.5 cm (shown approximately actual size)

emerged as an adjunct to architecture privileged work on a large scale, from the carvings of the Parthenon in Athens through the great masters of the Romanesque and Gothic churches to masterpieces of the Renaissance such as Michelangelo’s David (1501–4). On the other hand, the amulet was more orientated towards non-western traditions, and it was to these

that Moore was especially looking during the 1920s and 1930s. As with a few older artists, such as the sculptor Jacob Epstein (1880–1959), Moore’s interest in the art of non-western cultures in his earlier years was a key to his avant-garde identity as he sought in his art a form of authenticity distinct from the traditional, formal protocols of academic sculpture. The carvings of tribal Africa, Oceania and pre-Columbian central America, amongst many others, offered what appeared to be an emotional sincerity and carried with them some of the power that derived from their original sacramental functions. Similarly, Moore, like his avant-garde colleagues, sought sincerity through the practice of direct carving – the working of the sculpture by the artist themselves as opposed to a technician – and the doctrine of truth to materials that prioritised the artist’s immediate response to his wood or stone.

Manyof Moore’s early carvings were, of necessity, small in size. While he made a number of small wood carvings in the 1920s (p. 17), by far the majority were made from stone. Moore explored his identity as an Englishman through indigenous stones, but there was also, sometimes, a pragmatic side. In the early 1930s, he shared with fellow sculptors John Skeaping (1901–1980) and Barbara Hepworth (1903–

Head (verso), 1930 (LH 87a) ironstone, height: 7.5 cm (shown approximately actual size)

1975) the use of Cumberland alabaster and ironstone (pp. 21, 25, 26, 29). The former was dug out of Cumbrian fields by a farmer friend of Skeaping’s, while the three young sculptors discovered the latter as pebbles on Happisburgh beach in Norfolk. The ironstone came in small, thin, rounded forms and Moore sought to retain the pebble-ness of the original material.

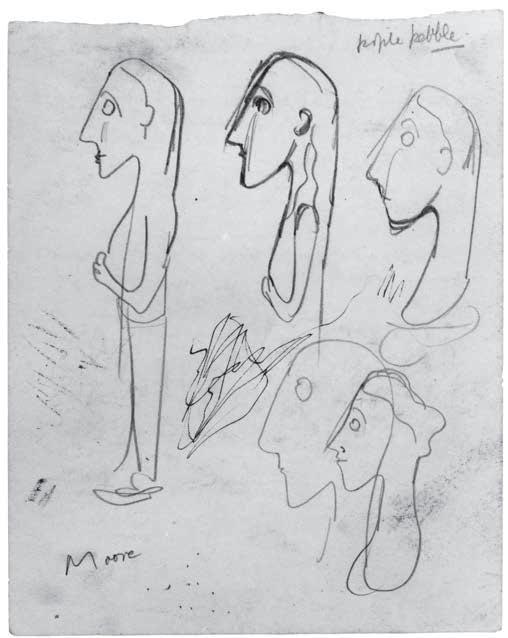

Page from a sketchbook of c. 1930–1, pencil on cream wove paper, 201 x 162 mm

The importance of this is indicated in a sketchbook where, by a drawing (ill. left) relating to Head (LH 88, p. 26), Moore wrote ‘profile pebble’.2 Skeaping recalled how Moore was compelled to work all of the time:

Henry accompanied me on one of my fishing trips but he couldn’t leave sculpture alone for long and took with him a piece of ironstone and a rasp. Sitting at one end of the boat he filed away continuously.3

The quotation gives a sense of the immediate, physical reality of Moore’s making sculpture and emphasises how that process was frequently one of the hand.

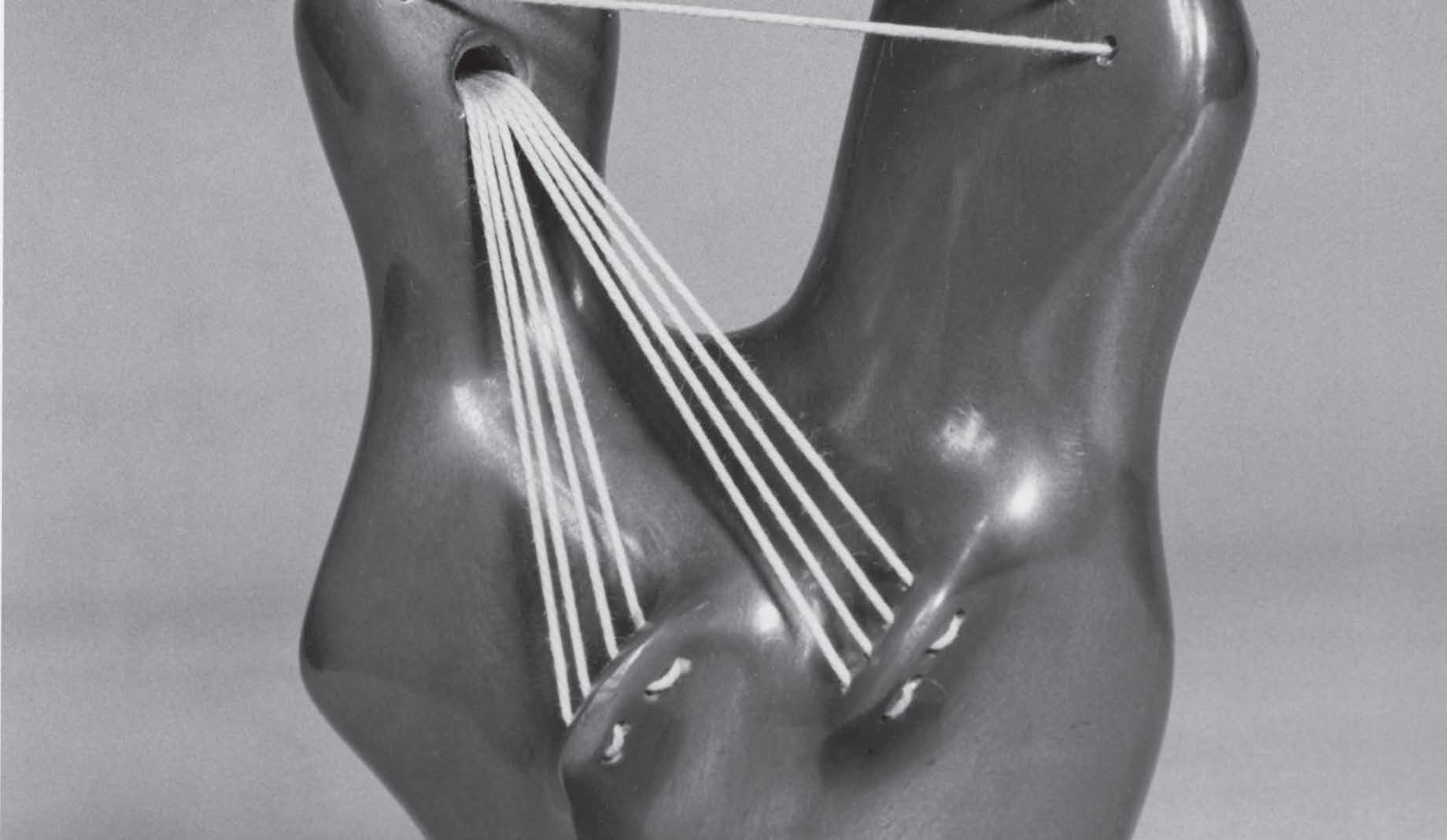

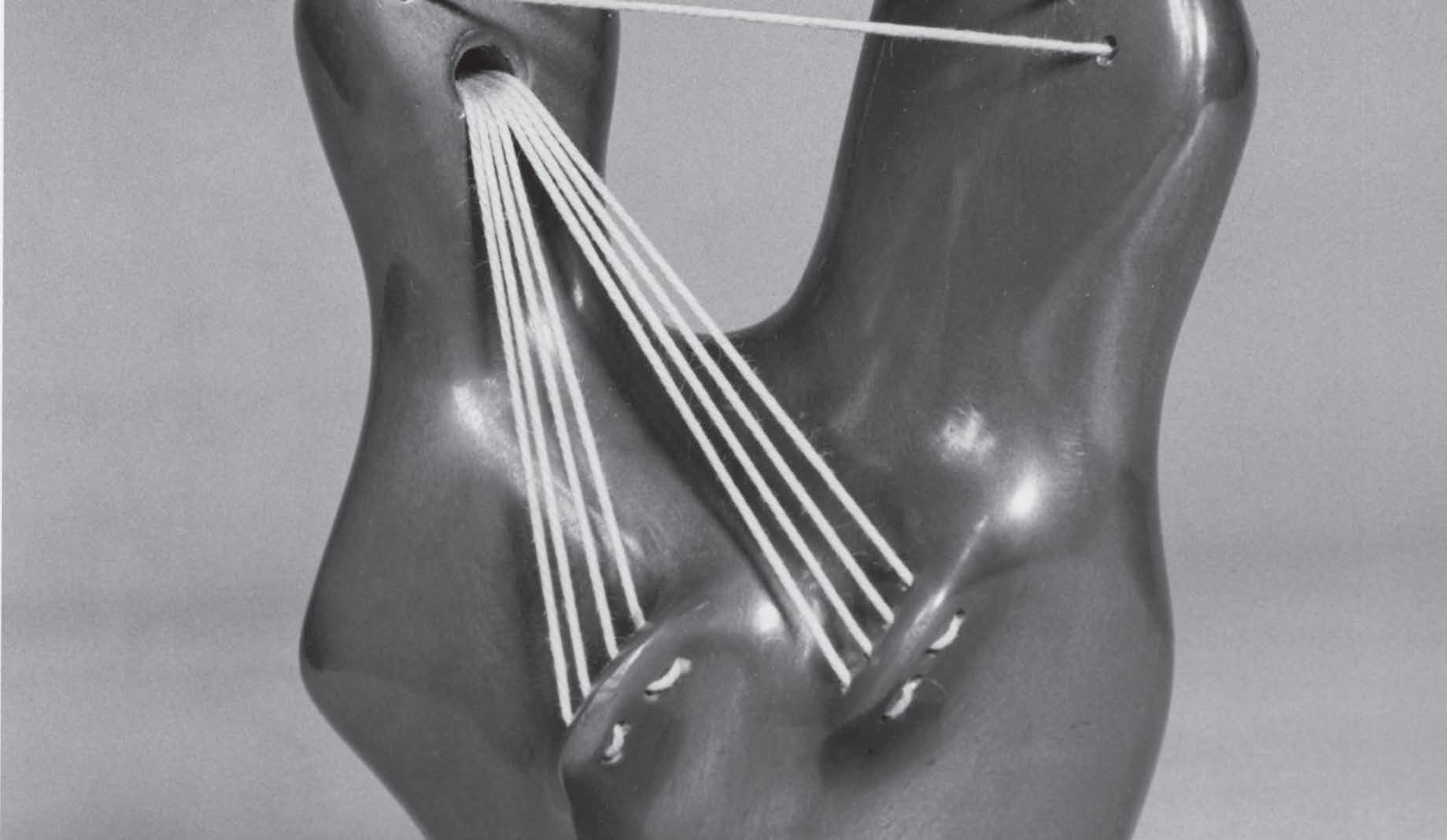

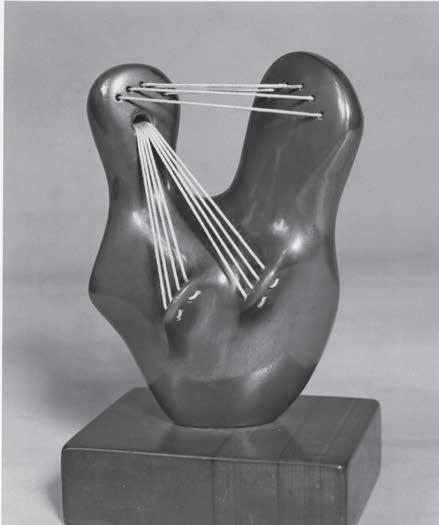

Theimmediacy of the hands-on process came, perhaps, to the fore when, in the later 1930s, Moore started to model his sculptures in malleable materials. He had used Plasticine very early on (p. 17) but had largely set it aside for carving. During the 1930s, when Moore was associated with both the abstract and surrealist tendencies in progressive art, his carvings moved away from the recognisable figure. While some stone carvings became almost machinelike in their rectilinear forms, reflecting perhaps the hardness of the African wonderstone from which a number were carved (p. 30), he also produced a series

of wooden carvings that were more curvaceous and biomorphic. Some incorporated taut strings which suited a finer, less massive sculptural form. As his carvings became more plastic in appearance, he realised he could achieve that quality through different materials. Moore had made odd pieces in lead since the end of the 1920s but in the last years of the 1930s he embraced the medium enthusiastically (pp. 34 and 37). The low melting point of lead meant the artist could cast works at home, using saucepans on the kitchen stove. Such works would first be modelled in a plastic material, most likely plaster that could be shaped around an armature when semi-dry and then carved and sanded when hardened. The cast metal allowed for finer, more elastic forms than wood or stone could tolerate, and Moore admitted he liked the fact that something about the appearance of lead told you that it was poisonous.

Moore’s small stringed sculptures appeared in a number of drawings as personages trapped in claustrophobic, prison-like rooms. In fact, during the 1930s, there was an increasingly complex interrelationship between Moore’s hand-scale sculptures –whether carved, modelled or cast – his ambition for larger, more public works, and his drawing. We see repeatedly sculptural forms that existed on a small scale appearing in drawings as if they stand majestically

in the landscape. Some of Moore’s best known and most ambitious carvings of that time appeared first modelled in wax, Plasticine or clay. Such maquettes exist for the Recumbent Figure (p. 46) that he made for the terrace of architect Bertold Lubetkin’s home overlooking the South Downs, for example, and for a number of the ambitious elmwood carvings that he produced over several decades (pp. 47, 48–9). Perhaps through necessity, terracotta became his major sculptural medium during the Second World War. Through his famous drawings of people sheltering in the London Underground, Moore then became as well known as a graphic artist as a sculptor and those drawings provided the germs for two important series of sculptures of the Madonna and Child (p. 40) and the Family Group (pp. 42 and 43). He produced a series of variations on the first theme in response to a commission for a large stone carving at St Matthew’s Church, Northampton. The Family Group had begun as a response to a particular commission but Moore’s numerous interpretations of the theme in terracotta, later cast in bronze, offered options as his work and that theme came to be closely associated with the new socio-political settlement following the war. Again, sculptures that would populate the new urban spaces of a post-war New Town, such as Harlow, had first been developed as a small hand-modelled piece of clay.

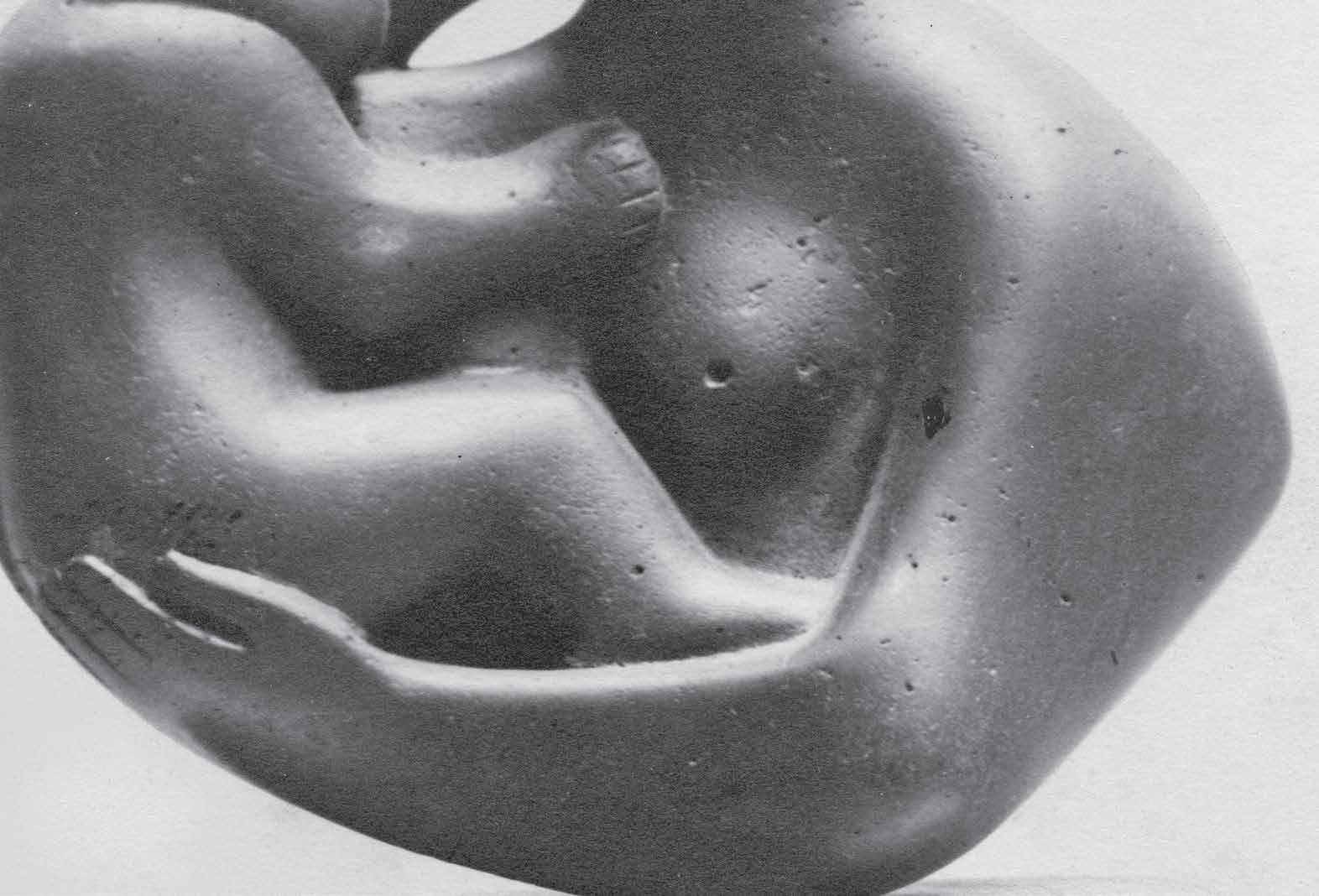

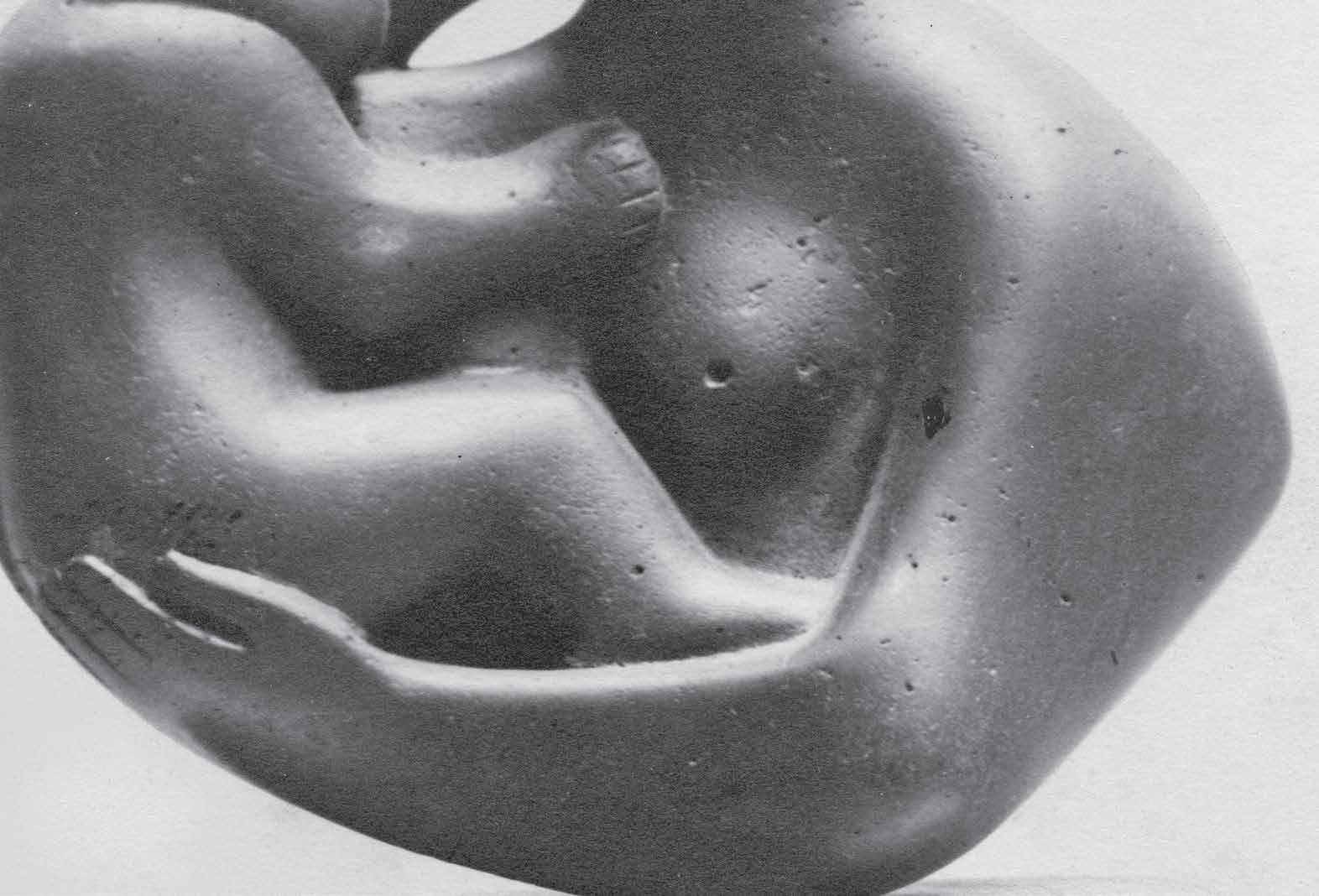

Mother and Child, 1930 (LH 86)

ironstone

height: 15.3 cm

Maternity, 1924 (LH 22)

Hopton Wood stone

height: 20.4 cm

Mother and Child, 1938 (LH 186) lead and yellow string

height: 11.9 cm