For Graciela, Carlotta, and Stefano —U.P.

front cover

Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 10010), from Stabiae, Villa San Marco, nymphaeum. Mosaic panel in glass tesserae, depicting a boxer and a rooster, detail of the boxer. First century ad (See plate 169.)

back cover

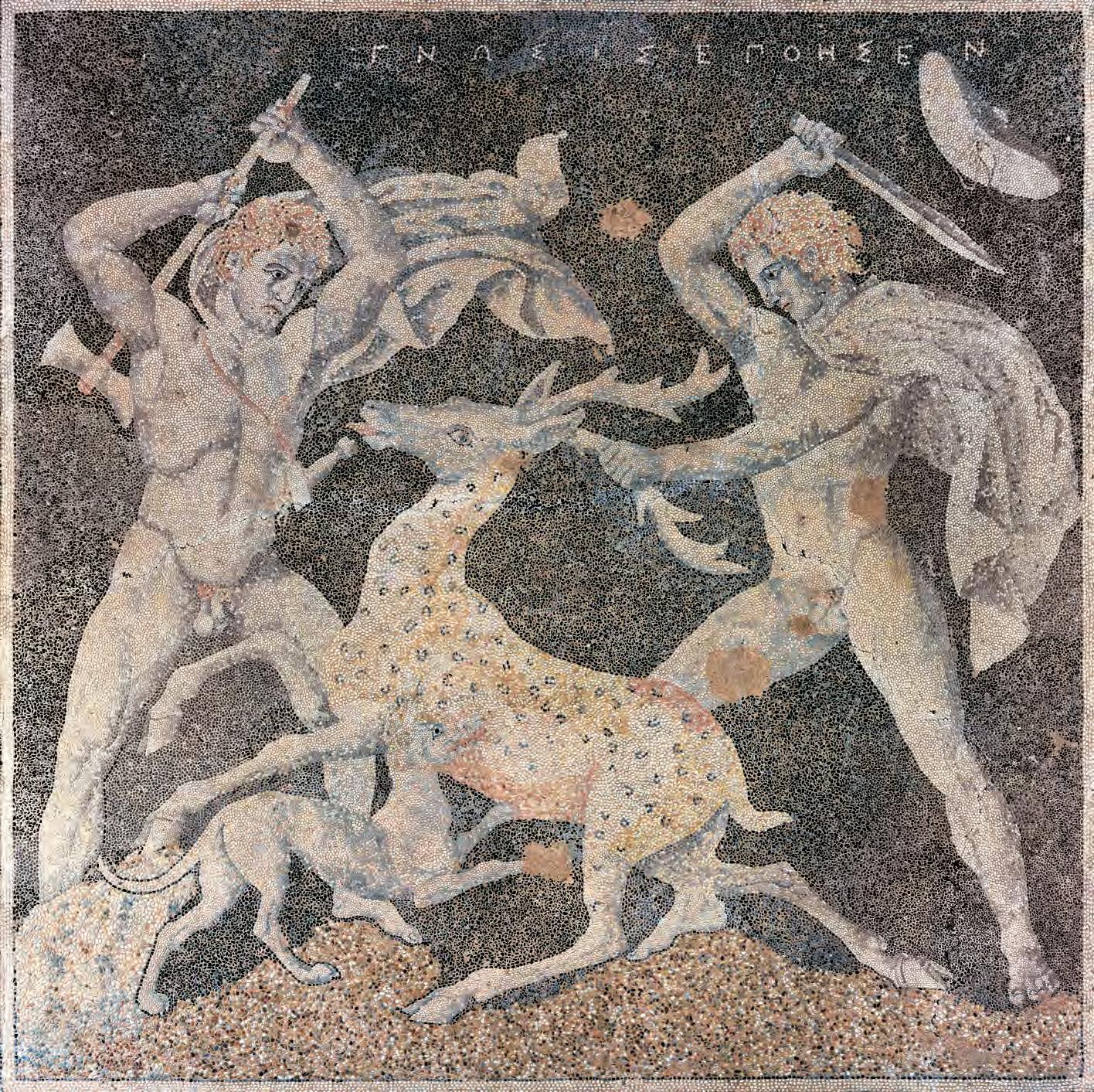

Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Antikensammlung (inv. Mos 1), from Tivoli, Villa Adriana, Sala a Tre Navate. Centaurs Fighting Wild Beasts, detail. Early second century ad (See plate 191.)

Rosaria Ciardiello is the author of the texts on pages 86–87, 115–19, 125–33, 167–68, 171–78, 185–86, 197–99, and 223–28, and the co-author, with Umberto Pappalardo, of those on pages 135 and 255–65; Umberto Pappalardo is the author of the rest.

First published in the United States of America in 2012 by Abbeville Press, 137 Varick Street, New York, NY 10013

First published in Italy in 2010 by Arsenale Editore Srl, Via Monte Comun 40, 37057 San Giovanni Lupatoto, Verona

Copyright © 2010 Arsenale Editrice. English translation copyright © 2012 Abbeville Press. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries should be addressed to Abbeville Press, 137 Varick Street, New York, NY 10013. The text of this book was set in Aldus. Printed in Italy.

First edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

For the original edition

Editorial director: Andrea Darra

Photographer’s assistant: Marco Pedicini

Administrative assistant: Annalisa Ciaravola

Editorial services: Oltrepagina, Verona

For the English-language edition

Editor: David Fabricant

Copy editor: Ashley Benning

Production editor: Stephanie Gomory

Production manager: Louise Kurtz

Composition: Kat Ran Press

Jacket design and typographic layout: Misha Beletsky

Pappalardo, Umberto, 1949 –[Mosaici greci e romani. English] Greek and Roman mosaics / Umberto Pappalardo, Rosaria Ciardiello ; photography by Luciano Pedicini ; translated from the Italian by Ceil Friedman. — First edition. pages cm

ISBN 978-0-7892-1125-5 (hardback)

1. Mosaics, Roman. 2. Mosaics, Hellenistic. 3. Mosaics, Byzantine. I. Ciardiello, Rosaria. II. Pedicini, Luciano. III. Title.

NA3770.P3513 2012 738.50937—dc23 2012026393

For bulk and premium sales and for text adoption procedures, write to Customer Service Manager, Abbeville Press, 137 Varick Street, New York, NY 10013, or call 1-800-Ar tbook.

Visit Abbeville Press online at www.abbeville.com.

CONTENTS

Introduction 7

The Origins and Spread of Mosaics 11

Etymological Considerations 15

The Method of Execution 17

Pliny and Vitruvius on Mosaics 21

Types of Mosaic 25

The Mosaicists and Their Signatures 35

Workshops and Repertories 46

The Dating of Mosaics 48

Mosaics and Textiles 51

Mosaics and Architecture 53

Wall and Vault Mosaics 55

The Stylistic Development of Mosaics 56

The Iconography of Mosaics 77

Bibliography 303

Index of Names 311

Index of Places 315

Photography Credits 319

THE MOSAICS

Pella 99

Alexandria 110

Pergamon 115

Delos 121

Palestrina 125

The House of the Faun at Pompeii 135

The Alexander Mosaic 153

The Fish Mosaic from the House of the Faun 167

Other Notable Dwellings of Pompeii 171

Nymphaea of the Vesuvian Cities 197

Mosaic Fountains of Campania 223

The Villa Adriana at Tivoli 231

The Musée National du Bardo, Tunis 243

Antioch on the Orontes 250

Piazza Armerina 255

The Basilica of Junius Bassus in Rome 275

The Great Palace of Constantinople 285

The Basilica of San Vitale at Ravenna 289

The Mosaic of the Holy Land at Madaba 300

THE METHOD OF EXECUTION

THE CRAFTSMEN

Over the centuries, the production of mosaics became increasingly refined and workintensive, so that by the late Roman period, it required a division of labor into various specialties, which are enumerated in Diocletian’s Edict on Prices and the Theodosian Code. A large project, such as the mosaic decoration of the Great Palace of Constantinople (plates 10, 221, and 222), could therefore involve many workers devoted to particular tasks: the pavimentarius, who prepared the ground on which the mosaic would be set; the pictor, who drew the design on the final layer of plaster; the tessellarius, who laid the greater part of the mosaic; and, finally, the musivarius, who composed the figurative sections. Of course, on a smaller project, a single person might perform more than one of these jobs.

THE MATERIALS

The earliest floor mosaics, dating to late fifth century BC, are composed of river pebbles, either black and white or colored. Subsequently, stone tesserae were used, first in floor mosaics, because they were resistant to wear and could be smoothed and polished, and later also in wall mosaics.

In general, the craftsmen procured the necessary stones on-site. Their preferred materials were limestone, tufa, and flint, all easily worked and occurring in a wide range of colors. However, when other hues were needed, they turned to imported stones, such as granite, porphyry, and alabaster from Egypt; white and rosso antico marble from Carrara; white, green, red, and black marble from Greece; and hard volcanic stone and veined marble from Asia. In the big cities, like imperial Rome, marble was sometimes obtained from the discarded fragments of large blocks imported for architectural purposes; later, after the fall of the empire, it could also be stripped from buildings that had fallen into disuse.

Glass tesserae, which produce marvelous effects of light, were already employed in the early empire, particularly to represent the sea: in Aquileia, for instance, there is an emblema of the first century AD representing Europa and the Bull, in which the refraction of the water is rendered in tesserae of blue and green glass (plate 11). The use of glass tesserae continued into the late empire, as can be seen in examples at Antioch on the Orontes, at Tabarca in present-day Tunisia, and in the basilicas of Bishop Theodorus (d. 319) at Aquileia. However, because glass tesserae were fragile underfoot, their most frequent application was in wall mosaics.

Gold tesserae—or rather, tesserae with gold leaf inserted between two layers of glass—had a notably intense hue, yet were also fragile and costly. They appeared for the first time in the ceiling of the Domus Aurea, and their use became more widespread beginning in the third century AD, reaching its maximum splendor in the Byzantine world.

opposite 10. Great Palace of Constantinople. Hunters. Late fourth to mid-sixth century AD.

MOSAICS AND ARCHITECTURE

As marble “carpets,” mosaics were adapted to the environments they decorated. In laying them out, care was taken that they would not be hidden by furniture.

For example, in the cubicula (bedchambers) of a Roman house, the figurative emblema was not placed in the center of the room, but rather between the two beds; similarly, in the triclinium (dining room), it was placed between the three couches, while a rich threshold decoration, usually with a meander pattern, marked the entrance to the room.

The subject of a mosaic could also emphasize the function of its setting. Still lifes of assorted foodstuffs have been found in triclinia, while depictions of fish, crustaceans, masks of rivers, and other aquatic motifs were common in the mosaic decoration of fountains and gardens; for instance, a pediment in the garden of the House of the Stags at Herculaneum displays a head of Oceanus at its center, above a frieze of Erotes riding seahorses. And at the entrance to a Roman house, a mosaic of a dog on a leash, accompanied by the inscription cave canem (beware of dog), might alert visitors to the presence of a canine guard.

Mosaics could interact with architecture in more formal ways as well. Sometimes their composition reflected, as in a mirror, the structure of the ceiling. Thus a mosaic with a rectilinear design might correspond to a beamed roof, and one with a curvilinear design—as in the oecus of the House of Julius Polybius at Pompeii, or in the Women’s Baths at Herculaneum—to a vaulted ceiling. This resemblance of floor to ceiling has allowed the reconstruction of many of the ceilings at Pompeii, such as those in the Villa of the Mysteries and the House of Menander.

Alternatively, a mosaic floor could be used to produce a kind of kinetic aesthetic, directing or interrupting the flow of foot traffic. For this reason, linear patterns were preferred for corridors and passageways, and more static compositions, often with a central figurative panel, for rooms and salons. In baths, white-ground mosaics with mainly geometric designs showed visitors which route to follow, almost like a conveyor belt.

In certain houses, the mosaic floors were completely integrated with the architectural design, forming a continuous decoration that extended across multiple rooms with various functions (plate 41). Of course, as we can see from examples like the House of Paquius Proculus on the elegant Via dell’Abbondanza in Pompeii, one reason for covering a home in mosaics was the desire of the owner—in this case perhaps a wealthy baker, or at any rate a “nouveau riche”—to show off the economic position he had attained. The Stoic philosopher Seneca (c. 4 BC–AD 65), an advisor to the emperor Nero, was moved to criticize this sort of excess: “When prosperity has spread luxury far and wide, men . . . devote attention to their houses—how to take up more space with them, as if they were country houses, how to make the walls glitter with marble that has been imported over seas, how to adorn a roof with gold, so that it may match the brightness of the inlaid floors” (Moral Epistles 114.9).

opposite

41. Pompeii, House of the Bear (VII.2.45). View of the atrium. First century AD

have been executed by craftsmen from North Africa, rather than from Rome or the eastern provinces. Their high level of artistry emerges in the interweaving of the various episodes; in the bold perspectives, foreshortenings, and twisting postures; and in a chiaroscuro that lends plasticity to the figures. Thus the decoration of the villa represents a return to Severan art, rather than an adherence to the new metaphysical expressionism; it is also marked by the lively polychromy characteristic of the mosaics of Roman North Africa.

The latter region has in fact yielded more mosaics than any other area of the empire. In part this is a reflection of the fact that North Africa was a rich and coveted territory,

56. Carthage, Musée National. Portrait of a woman, called the Lady of Carthage. Sixth century AD

made up of great imperial and private estates interspersed with smaller landholdings, generally belonging to veterans of the legions. Pliny remarks that in the first century AD, fully half the province of Africa Proconsularis (present-day Tunisia and western Libya) was in the hands of just six men, and that Nero had them murdered so he could take over their lands (Natural History 18.35); later sources report that the imperial estates accounted for one-fifth of the entire province. The region’s chief product was grain: if Egypt supplied Rome with enough wheat for four months of the year, Africa supplied enough for the other eight, almost 1.3 million tons. Wine and olive oil were also profitable exports.

57. Ravenna, Basilica of San Vitale. Detail of the Empress Theodora. Mid-sixth century AD

THE ICONOGRAPHY OF MOSAICS

CHARACTERISTIC THEMES

There is hardly any subject that is not represented in mosaic, be it mythological, literary, historical, erotic, or otherwise.

Sometimes, as we have mentioned in our discussion of mosaics and architecture, the theme was chosen to match its setting. Thus baths, fountains, and nymphaea routinely featured aquatic subjects: swimmers, fish, tritons, Nereids, Erotes on dolphins, and so on, as well as specific mythological figures, such as Narcissus, Poseidon and Amphitrite, Oceanus and Tethys, or Thetis on a hippocampus, bringing her son Achilles the new weapons forged for him by Hephaestus. In the gymnasiums, including those annexed to baths, we find the figures of athletes and fighters, such as those in the well-known mosaic from the Baths of Caracalla (c. AD 216) in the Lateran district of Rome.

For the triclinium, or dining room, the ideal subjects were still lifes of foodstuffs or Dionysian themes related to wine. There is also, of course, the famous invention of Sosos at Pergamon, the asarotos oikos, or Unswept Room, strewn with the remains of a banquet (plates 14–17 and 31–34). Equally engaging is the mosaic from Pompeii of a skeleton with a pitcher of wine in each hand, who reminds us to enjoy life while we can (plate 67). The bedrooms and women’s quarters, on the other hand, are distinguished by such themes as the toilette of Venus, the love of her son Cupid for Psyche, and Achilles among the daughters of Lycomedes.

Mosaics could also reflect the life and activities of those who commissioned them. Indeed, Roman artists, with their affinity for portraiture, sometimes depicted the owners of the houses they decorated. For example, in House VI.15.14 at Pompeii, dated to the first century AD, the owner had her likeness immortalized in an emblema vermiculatum inserted into the floor of the tablinum, or reception room (plate 59). Her appearance is one of aristocratic simplicity, with a sober hairstyle still in the Republican manner and a few pieces of jewelry—a string of pearls and amphora-shaped earrings— to lend a touch of elegance. These realistic details contrast with the somewhat stylized treatment of her features, which seems to anticipate the expressionism of later centuries. Overall, this portrait conveys the impression of a conservative provincial matron who takes care of her appearance and enjoys a comfortable life, while still embodying the virtues of morality, modesty, and seriousness prescribed in Plutarch’s roughly contemporary Advice to Bride and Groom

Certain mosaics commemorate the sources of their owners’ wealth. In the villa at Piazza Armerina, Sicily, the vast mosaic showing the capture of wild beasts in Asia and Africa and their transportation to the port of Ostia may record a profitable enterprise undertaken by the master of the house (plates 60, 211, and 212). In North Africa—for example, at Carthage—mosaics with Dionysian themes celebrate the rich production of wine, those with marine themes celebrate the abundance of fish, and those depicting fortified villas and the various labors of the field advertise the owner’s status as propri-

opposite 59. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 124666), from Pompeii, House VI.15.14, tablinum (h). Emblema vermiculatum with a portrait of a woman. 10 × 8 in. (25.5 × 20.5 cm). First century AD.

the future, my Leuconoe, like the past, / Whether Jove has many winters yet to give, or this our last” (Odes 1.11.3–4).

Indeed, the Romans well understood that death was common to all, and that it was, moreover, the true leveler of social differences, a point emphasized by a mosaic recovered from the triclinium of a house-workshop in Pompeii (plate 64): this memento mori depicts a skull between a surveyor’s level and a wheel of fortune, the latter surmounted by a butterfly, symbolizing the spirit. To the left of the skull are a scepter and a purple cloak, representing power and wealth, and to the right, a beggar’s stick and sack, representing poverty. Another ode of Horace, addressed to his friend Dellius, comes to mind: “Whether from Argos’ founder born / In wealth you lived beneath the sun, / Or nursed in beggary and scorn, / You fall to Death, who pities none” (Odes 2.3.21–24).

This philosophy must have been deeply rooted in the Roman psyche, for we also find, in a tomb of the second century AD on the Appian Way in Rome, a black-andwhite mosaic representing a skeleton lying on a bier, with the inscription gnothi sauton

opposite

64. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 109982), from Pompeii, House-workshop I.5.2. Memento mori. 35¾ × 27½ in. (47 × 41 cm). First century BC

left

65. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 109688), from Pompeii. Larva convivialis, or table ghost. Height 3½ in. (9 cm). First century AD.

page 142

110. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 9994), from Pompeii, House of the Faun (VI.12.2), threshold of the fauces. Festoon with tragic masks, detail of a mask. Late second century BC

page 144

112. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 9991), from Pompeii, House of the Faun (VI.12.2), triclinium (34). Winged Dionysus on a Tiger, 64¼ × 64¼ in. (163 × 163 cm). Late second century BC

page 146

114. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 27707), from Pompeii, House of the Faun (VI.12.2), cubiculum (28). Mosaic with satyr and maenad, 15½ × 14½ in. (39 × 37 cm). Late second century BC

pages 150–51

117. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 9991), from Pompeii, House of the Faun (VI.12.2), triclinium (34). Winged Dionysus on a Tiger, detail. Late second century BC

page 141

109. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 5002), from Pompeii, House of the Faun (VI.12.2), Tuscan atrium. Bronze statuette of dancing faun.

page 143

111. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 9994), from Pompeii, House of the Faun (VI.12.2), threshold of the fauces. Festoon with tragic masks, detail of a mask. Late second century BC

page 145

113. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 9991), from Pompeii, House of the Faun (VI. 12.2), triclinium (34). Winged Dionysus on a Tiger, detail of a mask in the bottom part of the border. Late second century BC

page 147

115. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 9993), from Pompeii, House of the Faun (VI.12.2), ala (30). Mosaic of pantry shelves, 20 × 20 in. (51 × 51 cm). Late second century BC

pages 148–49

116. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 9993), from Pompeii, House of the Faun (VI.12.2), ala (30). Mosaic of pantry shelves, detail of a cat attacking a quail. Late second century BC.

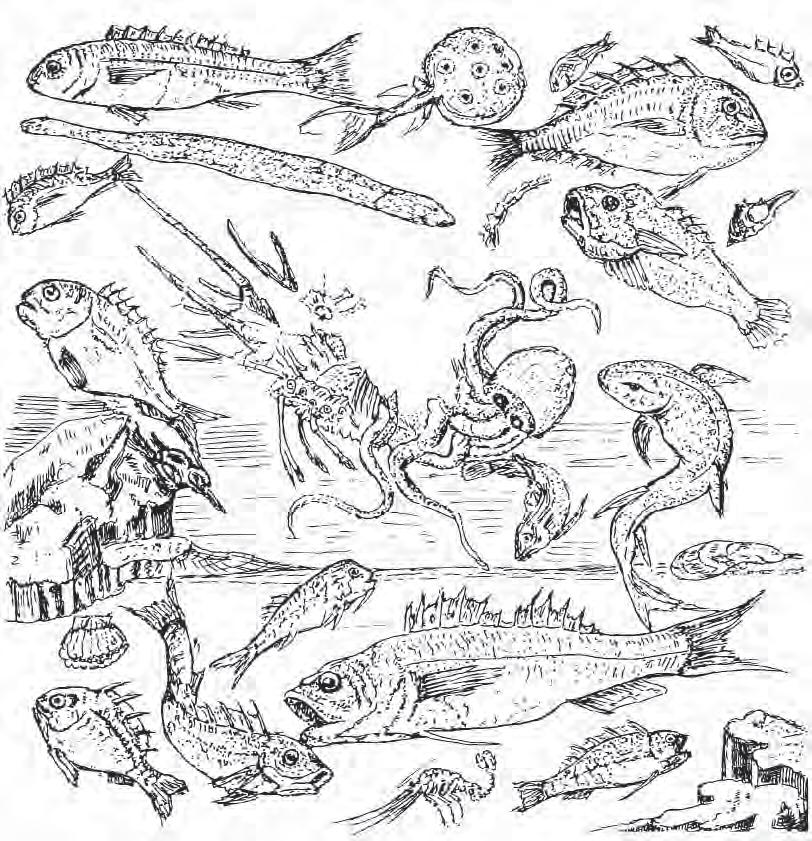

128. Graphic rendering of the fish mosaic from the House of the Faun.

1) Liza aurata, golden mullet

2) Torpedo torpedo, common torpedo

3) Diplodus annularis, annular sea bream

4) Sparus aurata, gilthead bream

5) Diplodus sargus, white sea bream

6) Sparus pagrus, common sea bream

7) Muraena helena, Mediterranean moray

8) Scorpaena scrofa, red scorpionfish

9) Murex brandaris, murex

10) Dentex dentex, common dentex

11) Palinurus vulgaris, European spiny lobster

12) Octopus vulgaris, common octopus

13) Trigla sp., gunard

14) Scyliorhinus stellaris, dogfish

15) Penaeidae, prawn

16) Pecten jacobaeus, scallop

17) Diplodus vulgaris, sea bream

18) Trigla sp., gunard

19) Mullus barbatus, red mullet

20) Dicentrarchus labrax, European sea bass

21) Leander sp., shrimp

22) Serranus cabrilla, comber

129. Naples, Museo Archeologico

Nazionale (inv. 9997), from Pompeii, House of the Faun (VI.12.2), triclinium (35). Fish mosaic, 46 × 46 in. (117 × 117 cm). Late second century BC.

You catch them large and good off Nestor’s home. Have I passed by the black-tail and the “thrush,” the sea-merle and the shadow of the sea?

Best to Corcyra go for cuttle-fish, for the acarne and the fat sea-skull the purple-fish, the little murex too, mice of the sea and the sea-urchin sweet.

This predilection for the fruits of the sea only intensified in the Roman era, if we may judge from the epigrams that Martial devoted to the subject; epigram 13.91, for example, affirms that sturgeon was as rare a delicacy in his day as in ours: “Send the sturgeon to the Palatine table; such rarities should adorn divine feasts.” According to other sources, wealthy Romans frequently maintained their own fishponds. The orator Quintus Hortensius Hortalus (114–50 BC) was well known for constructing, at great expense, saltwater ponds for moray eels, mullets, and oysters at his villa at Bauli, on the Bay of Naples; Varro records that Hortensius fed his fish personally (On Agriculture 3.17), and Pliny even maintains that the orator cried desperately when his favorite eel died (Natural History 9.172). Mark Antony’s daughter Antonia Minor is said to have put earrings on her own favorite eel (ibid.), and on a more sinister note, the wealthy official Vedius Pollio (d. 15 BC) supposedly fed the eels, or lampreys, in his fishponds with human blood (Seneca, On Clemency 1.18.2).

156. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 9995, 9996, 10000, 10001), from Pompeii, Villa of the Mosaic Columns, garden. Four columns with mosaics in glass tesserae, with shells at the base. Height 9 ft. (2.75 m). First century AD opposite

157. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale (inv. 10000), from Pompeii, Villa of the Mosaic Columns, garden. Detail of imbrication on a mosaic column First century AD

rare to find serious mythological themes represented in a nymphaeum, as we do in the one at the back of the garden of the House of Apollo (VI.7.23). Here a small mosaic representing the Discovery of Achilles on Skyros is still in situ (plate 158), while two others were removed to the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples in 1839. One of these depicts the Wrath of Achilles, in which Athena restrains the hero from attacking Agamemnon as he sits on his throne (plate 159), while the other represents the Three Graces in the traditional Hellenistic composition of embracing figures seen alternately from the front and back (plate 151), a scheme Raphael would reprise in his famous painting of this subject, now in the Musée Condé in Chantilly.

THE HOUSE OF THE SKELETON AT HERCULANEUM

Partially explored in 1830–31, and systematically excavated by Amedeo Maiuri in 1927–28, the House of the Skeleton was created through the combination of three ear-

pages 268–69

212. Piazza Armerina, Sicily, Roman villa, corridor of the Great Hunt (14). Detail of a tiger hunt in India using a glass sphere. Early fourth century AD.

pages 272–73

214. Piazza Armerina, Sicily, Roman villa, cubiculum (20). Children hunting, detail. Early fourth century AD.

page 267

211. Piazza Armerina, Sicily, Roman villa, corridor of the Great Hunt (14). Detail of the capture of a griffin with a human lure enclosed in a cage. Early fourth century AD.

pages 270–71

213. Piazza Armerina, Sicily, Roman villa, apsidal hall (18), perhaps a library. Arion on the Dolphin, detail of a triton, and an Eros on a sea monster. Early fourth century AD

pages 280–81

219. Rome, Museo Nazionale Romano, from the Basilica of Junius Bassus. Scene of Hylas and the Nymphs above a fictive curtain fringed with Egyptianizing motifs, detail of the mythological scene. Circa AD 331.

pages 278–79

218. Rome, Museo Nazionale Romano, from the Basilica of Junius Bassus. Processus consularis of Junius Bassus. Circa AD 331.

pages 282–83

220. Rome, Musei Capitolini, Palazzo dei Conservatori, from the Basilica of Junius Bassus. Tiger attacking a calf. Circa AD 331.