The Garden where it all Began

Once upon a time, there was a garden. A garden where everything was always in bloom. There were no dead leaves, no faded roses, no mucking about in the soil sowing seeds and hoping they come up. Just a perfect paradise, full of colour and scent, where time held no sway.

But that was to leave man out of the equation. For give a person perfection, and very soon they’re wanting more. Eve picks a fruit, Adam takes a bite, and wham! Goodbye garden, hello chaos. Suddenly everything has to be planted, weeded, harvested. The carousel of the seasons goes relentlessly round, animals gobble each other up, and for man there’s unending toil: sowing, tending, reaping.

Paradise now is not a place but a pipe dream. The world outside is full of peril, the playground where the devil gets his jollies. He roams the wilds, conjuring marshlights that lure the unwary into bogs and mires, then scarpering with their souls. He lurks behind trees in endless forests full of wolves and bears and brigands, terrifying travellers to death. The pious believer would do better to stay safely indoors and creep into a corner with a book. God didn’t reveal himself in the Word by accident: if you want to get an inkling of the divine mystery, all you need do is read your prayer book (though maybe shut the curtains first).

In the margins of those books, flowers are popping up ever more often. At first, they’re mainly symbolic. They speak in a code that would show us the way to heaven if only we could understand it. For paradise

may be a lost cause, but the Almighty is a man with a plan. Creation is littered with his ciphers. Crack the code and voilà!, the divine mystery is revealed. And thus, a white lily represents Mary’s purity, a violet or a wild strawberry her humility. But the Virgin is also an ‘enclosed garden’, fertile, even though her entryway is closed.

Nature, it seems, is a manuscript. But why sit there reading when you could just as easily go for a walk? Little by little, man craves more. He’s no longer happy simply to accept. He wants to understand.

Believe it when You See it

The first cracks in the old worldview appear in the Southern Netherlands, that marshy patchwork of duchies and counties and whatnot beside the grey North Sea. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, first Bruges, then Antwerp hold sway as the teeming heart of Europe. Here, merchants from all over the known world cross paths in streets that smell of spices, wet wool, and printing ink. Here, fortunes are won and lost, and the latest ideas circulate with increasing speed. Art, science, and trade – here they go hand in hand.

In the thronging streets and crowded markets, a new type of person is born: the entrepreneur. This is no knight living off his lands, no monk withdrawn into an abbey. This is someone who looks at the world with unblinkered eyes, who’s ready to take risks and prepared to draw their own conclusions.

Tulipomania notwithstanding, the flower remained an inexhaustible source of inspiration for artists. As mentioned earlier, there were many drawings of tulips in circulation in the seventeenth century, and even entire tulip books full of ‘portraits’ of the most expensive varieties. But as far as I was able to discover, among all those flowers, not a single one looked like the tulip in Brueghel’s painting.

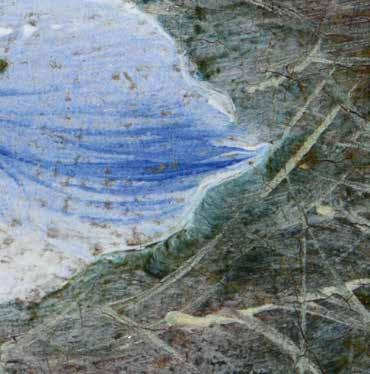

Nevertheless, Brueghel almost certainly first made a drawing of the yellow-pink-blue tulip before working it out in oil. He would have noted the flower’s characteristics in watercolour or body colour on paper, much like the nature studies of Anselmus De Boodt (see Chapter 1). Doing so enabled him to make a rapid record of transient models like flowers that he could later incorporate into a complex bouquet.

Where did those drawings go? When Jan Brueghel I died, many of his natural-history studies would likely have passed to his children and grandchildren, most of whom became painters as well. Many of them produced flower still lifes and could use the sketches for their own work, as we shall see later on. With such intensive use, those fragile drawings may simply have worn out. In an anonymous work entitled Nieuwen verlichter der konst-schilders, vernissers, vergulders en marmelaers (1777), for instance, we read that Breughel’s grandson, Jan Van Kessel I, also used studies from nature to compose his own bouquets, just as his grandfather had done.

‘Van Kessel hadde voor maniere van op de verscheyde Saisoenen te studeren: hy teekende en schilderde die ook; maer hy modelleerde ze voor het meeste deel. Vervolgens, als hy eenige Schilderyen wilde maeken, ging hy tot zyne studien, van de welke hy eene groote vergaederinge hadde: dezen zelven toegang heeft aen zynen zoon.’ (‘Van Kessel had a way of studying [the flowers of] the different seasons: he also drew and painted them; but for the most part he modelled them. Then, when he wanted to produce a few paintings, he went to his studies, of which he had a large collection: his son had equal access to them’).12

JAN VAN KESSEL I

Vase of Flowers with Tulips, Roses, Anemones and an Iris, c.1660

Oil on panel, 52 × 36 cm

ANTWERP , THE PHOEBUS FOUNDATION

Brueghel’s correspondence with his Italian patron, Cardinal Federico Borromeo (1564-1631), also gives us a glimpse of how he worked, as he describes how he travels to ‘portray’ flowers. He made several trips from Antwerp to Brussels, for instance, specifically to observe particular flowers at first hand, most likely in the gardens of the Coudenberg Palace, where the Archdukes Albert and Isabella maintained a collection of both native and exotic fauna and flora.13

All these sketches and drawings were essential preparatory material for the compositions Brueghel would subsequently paint in oil. I imagine him moving his flower studies around on a board and pinning them in place when he was finally satisfied with the arrangement. The long-stemmed tulips and irises at the top, the small shorter flowers at the bottom. Of course, working like that also meant that he could combine flowers that bloomed in different seasons. Although most of the flowers in Flowers in a Vase with a Clump of Cyclamen and Precious Stones bloom in spring, like the tulip, there are also species that are at their best in winter, such as the cyclamen and the hyacinth.

Throughout his career, Brueghel used his collection of sketches to work out the composition of pictures he would later paint in oil. Although his painted bouquets obviously differ from each other, many of the individual flowers in them are identical in size and colour.14

PP. 104-105

JAN BRUEGHEL I

Study of Apples, Pears, Grapes, Blackberries, an Artichoke, Spears of Asparagus and a Sprig (detail), c.1600-1610

Oil on panel, 52.8 × 68.8 cm

ANTWERP , THE PHOEBUS FOUNDATION

1 Analysis was carried out using false-colour IRR and handheld XRF.

2 On the use and price of ultramarine blue, see S. Nash,‘“Pour couleur et autres choses prise de lui...”: The Supply, Acquisition, Cost and Employment of Painters Materials at the Burgundian Court, c.1375-1419’, in: J. Kirby, S. Nash & J. Cannon (eds.), Trade in Artists’Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700, London, 2010: 97-182.

3 R. Woudhuysen-Keller, Das Farbbüechlin Codex 431 aus dem kloster Engelberg band II Bearbeitung, Riggisberg, 2012: 167-175.

4 On the preparation of indigo dye, see the manual Kremer Pigmente.Dyeing with Indigo,s.l.,s.d.

5 R. Dodoens, Cruydt-boeck, Antwerp, 1563: 57.

6 A. Pavord, TheTulip, London, 1999: 4.

7 K. Van Cauteren,‘De eerste tulp in Europa?’, in: R. Born, M. Dziewulski & G. Messling (eds.), Het rijk van de sultan. De Ottomaanse wereld in de kunst van de renaissance, exh. cat., Kraków, Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Brussels, Bozar, 2015: 135.

8 F. Egmond & S. Dupré,‘Collecting and Circulating Exotic Naturalia in the Spanish Netherlands’, in: S. Dupré, B. De Munck, W.Thomas et al. (eds.), EmbattledTerritory:The Circulation of Knowledge in the Spanish Netherlands, Ghent, 2015: 215.

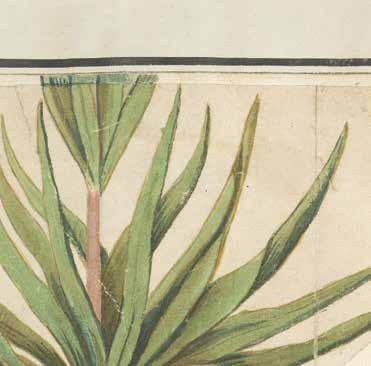

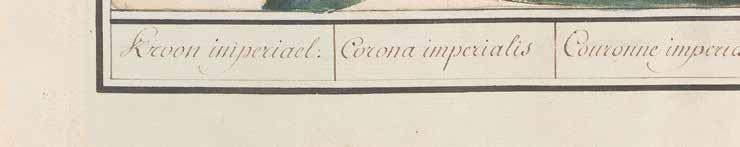

9 C. Clusius, Rariorum Plantarum Historia, Antwerp, 1601.

10 E. Sweert, Florilegium, Amsterdam, 1612.

11 Pavord 1999: 61-62.

12 Nieuwen verlichter der konst-schilders,vernissers,vergulders en marmelaers,en alle andere liefhebbers dezer lofbaere konsten, Ghent, 1777: 135.

13 K. Van Cauteren, Politics as Painting.Hendrick De Clerck (1560-1630) and the Archducal Enterprise of Empire, Tielt, 2016: 343.

14 S. Van Dorst, Flowers in a Vase with a Clump of Cyclamen and Precious Stones.A Gem of a Painting by Jan Brueghel I (1568-1625), Phoebus Focus, 28, Veurne, 2022: 59-61.

15 On Mayken Verhulst, see L. Huet, Mevrouw Renaissance.Of het leven en werk van stammoeder Brueghel, Antwerp, 2019.

16 On Federico Borromeo, see P.M. Jones, Federico Borromeo and the Ambrosiana:Art Patronage and Reform in Seventeenth-Century Milan, Milan, 1997.

17 A.K. Weelock Jr., From Botany to Bouquet: Flowers in Northern Art, Washington, 1999: 48.

18 On the Brueghel family, see N. Groeneveld-Baadj, A. Difuria, C. Göttler et al., Brueghel: de familiereünie, Zwolle, 2023.

19 On Pieter Brueghel II’s copying practice, see P. van den Brink, De Firma Brueghel, Brussels, 2001.

20 J. Denucé, Brieven en documenten betreffend Jan Breugel I en II. Bronnen voor de geschiedenis van de Vlaamsche kunst, 3, Antwerp, 1934: 94-95.

21 On the Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta, see L. Hendrix & T. Vignau-Wilberg, Nature Illuminated: Flora and Fauna from the Court of Emperor Rudolf II, Los Angeles, 1997.

22 My thanks to Anne Woollett and Elizabeth Morrison of the J. Paul Getty Museum for sharing their insights with me.

23 My thanks to Philippe De Potter for information about the engravings made after drawn or painted ower still lifes by Jacob Savery I.

24 My thanks to Marije Verduijn and Marie-Fleur Dijk for the opportunity to study this work in the depot of the Centraal Museum Utrecht. A blue tulip also appears in Roelandt Savery’s Bouquet of Flowers from 1612, now in Liechtenstein,The Princely Collections, Vaduz-Vienna, inv. GE00789.

25 My thanks to Anne Woollett and Elizabeth Morrison for drawing this to my attention.

26 H. Mulder, De ontdekking van de natuur, Amsterdam, 2021: 59 and M.-C. Maselis, A. Balis & R.H. Marijnissen, De Albums van Anselmus De Boodt (1550-1632): Geschilderde natuurobservatie aan het hof van Rudolf II te Praag,Tielt, 1989: 73-74.

27 Mulder 2021: 55-60.

28 See Joris Hoefnagel, The Four Elements, Rosenwald album 120530: fol. 47 and the Museo del Prado image database (inv. P001418) for an image of Jan Brueghel I and Peter Paul Rubens’s Virgin and Child Surrounded by Fruit and Flowers.

29 E.J.O. Kompanje,‘“Lepus cornutus” een haas met een gewei: een mythologisch wezen, een grap van de taxidermist of realiteit?’, Straatgras, 16, 4 (2000): 45-47.

30 M. Mandabach,‘Matter as an Artist: Rubens’s Myths of Spontaneous Generation’, Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, 13, 2 (2021): 6.

31 P. Mason,‘“Cobras da Índia de duas cabeças não fazem mal” Codex Casanatense 1889, . 91’, Anais de História, 13 (2012): 161-168.

32 Johan Faber wrote in 1628 that a two-headed snake had been found in Mexico, then part of the Spanish Empire. For more on this, see U. Härting in De dynastie Francken, exh. cat., Cassel, Musée de Flandre, 2020: 45.

33 W. van Dijk, ATreatise onTulips by Carolus Clusius of Arras, translated by W. van Dijk, Haarlem, 1951: 14.

34 On Giuseppe Arcimboldo, see S. Ferino-Pagden (ed.), Arcimboldo 1526-1593, Milan, 2007.

Let’s go back to Oxford for a moment, to the vase of flowers by Ambrosius Bosschaert I in the Ashmolean Museum. The similar composition of that work enables us to link it to the drawing beneath little Pieter van Delen’s deathbed portrait and attribute it to the workshop of Ambrosius Bosschaert I. Bosschaert ran a large workshop, and his pupils were trained to use a painting technique similar to his, known in the seventeenth century as the master’s maniere or manner. 25 Today we might call it ‘branding’ or a trademark style. Bosschaert’s pupils were required to become thoroughly proficient in his specific maniere.

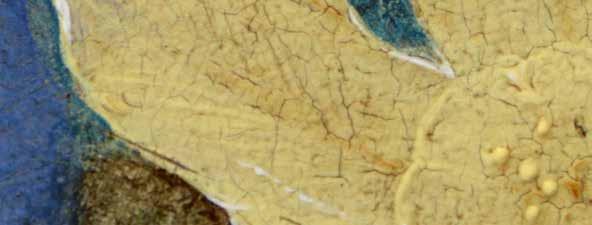

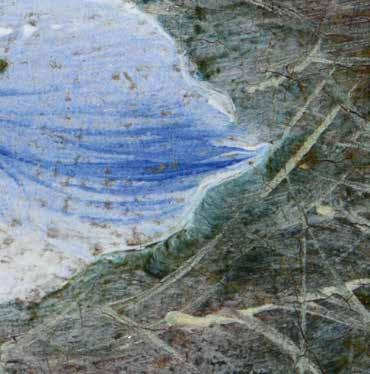

By 1605, the year in which he signed his first flower still life, Ambrosius Bosschaert I’s style reached full maturity. 26 He had painted flower pieces before that, albeit in a fairly subdued style. Now, influenced by the work of Jan Brueghel I, he began to produce naturalistic and lively bouquets. 27 Brueghel had just returned to the Low Countries after his stay at the imperial court in Prague (see Chapter 2). 28 Whether the two artists ever met in person is not known, but it is clear that Bosschaert had seen Brueghel’s work. He actually copied some of Brueghel’s flowers and incorporated them into his own compositions. 29 For example, almost identical tulips, including the ‘blue’ tulip, appear both in Bosschaert’s 1609 Vienna bouquet and Brueghel’s Flowers in a Vase with a Clump of Cyclamen and Precious Stones from a few years earlier. Although Bosschaert found inspiration in the work of his Antwerp colleague, he nonetheless maintained his own recognizable technique, using more body colour in larger areas, for instance. The result is very different from Brueghel’s transparent and nervous brushstrokes.

The same selection of flowers appears repeatedly in Bosschaert’s work, indicating that he arranged his compositions using his own large collection of study drawings. Sometimes he reversed the drawings, so that a flower seen one way round in one painting would appear the other way round in another.30 By tracing the studies onto the support via the method described earlier, he was able to transfer his composition very quickly, as evidenced by the crisp, almost mechanical underdrawings that are often found beneath his paintings. His Vase of Flowers with a Poem Dedicated to the Artist (1621), now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, is a fine example. The mechanical character of the lines (revealed by IR and IRR) is identical to the drawing beneath the deathbed portrait of little Pieter van Delen.

Ambrosius Bosschaert I in turn passed on his ‘manner’ to his pupils, including his three sons and his brothersin-law. They learned the craft by following his example and imitating his working processes. They also had access to his study drawings, which is why the same flowers appear in their work, and frequently copied his method of transferring the underdrawing to the support. In infrared images of paintings by Ambrosius II and Johannes Bosschaert, we see the same sharp mechanical lines as in his father’s work.31

IRR also shows that the individual elements in the underdrawing of Balthasar van der Ast’s Still Life with Flowers, Fruit, Shells and a Salamander, painted around 1620, are likewise firmly outlined. Yet his working method is slightly different, for he reinforced the chalk lines with a fine brush using dark paint or ink.32 In some parts of the painting, those dark lines can now be seen with the naked eye, having gradually become visible through the layers of paint. Perhaps Balthasar began to use that method after he opened his own workshop in Utrecht.

Sven Van Dorst (1990) gained his Master’s in Conservation-Restoration at the Royal Academy/ University of Antwerp. After working at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, he completed his training at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, a department of Cambridge University.

In 2016, Sven founded the conservation studio of The Phoebus Foundation. As head of the studio, he assembled a team of passionate restorers and conservation scientists who manage the Foundation’s collection on a daily basis. Among the paintings he has treated are works by masters such as Peter Paul Rubens, Jacob Jordaens, Anthonis Mor and Michaelina Wautier.

Between 2017 and 2020, Sven led the research and restoration project of the panels of the Dymphna altarpiece by Goossen Van der Weyden. His deep interest in the painting techniques and materials of Baroque flower painters has already led to three editions of the Phoebus Focus series, on Daniel Seghers, Jan Brueghel I, and Jan Davidsz. De Heem.

ACADEMIC EDITOR

Katharina Van Cauteren

AUTHOR

Sven Van Dorst

CONTENT EDITING & COORDINATION

Leen Kelchtermans

PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Hedwig Scheltjens

Hadewych Van den Bossche

EDITING

Elizabeth Vandeweghe

Mark Van Steenkiste

TRANSLATION

Lee Preedy

COPY EDITING

Xavier De Jonge

IMAGE RESEARCH

Laura Geudens

Séverine Lacante

Sven Van Dorst

Helena Vanloon

PICTURE EDITING

Tineke Deriemaeker

Séverine Lacante

GRAPHIC DESIGN

Paul Boudens

PRINTING & BINDING

die Keure, Bruges

PUBLISHER

Gautier Platteau

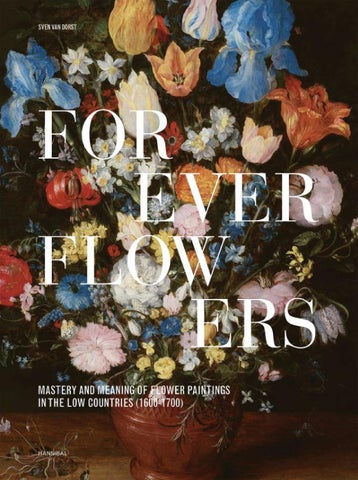

COVER

JAN BRUEGHEL I

Flowers in a Vase with a Clump of Cyclamen and Precious Stones, c.1605-1607

Oil on panel, 51 × 41 cm

ANTWERP , THE PHOEBUS FOUNDATION

BACK COVER

OSIAS BEERT I

Flowers in a German Tigerware Vase (detail), c.1600-1610

Oil on panel, 75.3 × 54 cm

ANTWERP , THE PHOEBUS FOUNDATION

ENDPAPERS

Details of Vase of Flowers with Vanitas Symbols (p. 206), Mary Crushing the Serpent in a Garland of Flowers (p. 166), Marriage of Joseph and Mary in a Garland of Flowers (p. 132), Vase of Flowers with Tulips, Roses, Anemones and an Iris (p. 102), The Child Mary Spinning in a Garland of Flowers (p. 340) and Virgin and Child with Crown Imperial and Llama (p. 28)

ISBN 978 94 6494 190 6 D/2025/11922/16 NUR 646

© HANNIBAL BOOKS, 2025 WWW.HANNIBALBOOKS.BE

© THE PHOEBUS FOUNDATION

PUBLIC BENEFIT FOUNDATION|STICHTING VAN OPENBAAR NUT, 2025 WWW.PHOEBUSFOUNDATION.ORG

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders for all texts, photographs and reproductions. If, however, you feel that you have inadvertently been overlooked, please contact the publisher.