Marieke van Schijndel, director of Museum

Catharijneconvent

Fashion for God is the intriguing title of an exhibition about Catholic church vestments in the period of the clandestine churches in the Netherlands, at Museum Catharijneconvent from 13 October 2023 to 21 January 2024. An intriguing title for an extraordinary exhibition. Fashion is often temporary, transient, whereas church vestments seem to represent the importance of the eternal. The title does not refer to merely any old fashion, however, but fashion for God. Fashion made to honour God. Fashion for God tells the story of an art form that is the quintessential expression of identity. This publication is about the artistic splendour of precious ecclesiastical textile, about the identity of the Catholic church in times of oppression, and about those who made, wore and donated these garments.

The story behind Fashion for God and this publication is a long one. It begins with the previous exhibition on ecclesiastical textiles in 2015. Soon after the success of The Secret of the Middle Ages in Gold Thread and Silk, it became clear that a follow-up exhibition would be needed, focusing on post-Reformation ecclesiastical textiles: a part of the richly varied, unparalleled and fragile collection of Museum Catharijneconvent that is well worth exploring and studying in detail.

Various churches in the Netherlands also house a treasure trove of ecclesiastical textiles from the period up to 1800, many of these priceless items still kept in the place for which they were made. Interestingly, they tend to be Old Catholic churches. The Old Catholic Church and the Old Catholic Museum, one of the forerunners of Museum Catharijneconvent, are an invaluable source, for which the curators of this exhibition are very thankful.

2023 and 2024 are memorable years for the Old Catholic Church, as it commemorates the election of Cornelis Steenoven as Bishop of the Netherlands in 1723 and his consecration in 1724. This cemented the schism between the Roman Catholic Church and the Old Catholic Church in the Netherlands. Fashion for God shows in unexpected ways how this part of church history can be told through ecclesiastical textiles.

We are grateful to the Old Catholic Church of the Netherlands for its generous loans of its textile heritage. Thanks also to the funds that sponsored the publication, and in particular to Frank Vroom, whose Frank N. Vroom Fund paid for the restoration of some important pieces. The academic research on the ecclesiastical textiles collection was awarded a museum grant by the Dutch Research Council, and was partially funded by Ms De Boeck-Rinkel’s bequest for the preservation of Old Catholic heritage. I would particularly like to thank Dr. Richard de Beer and Pim Arts for compiling this catalogue, all the other authors who wrote a contribution, and expert advisors Professor Peter-Ben Smit, Dr. Dick Schoon, Dr. Marike van Roon and Dr. René Lugtigheid for their invaluable advice.

This important publication and the exhibition it accompanies would not have been possible without the vital input and support of many parties.

Introduction

Richard de Beer and Pim Arts

Since time immemorial, textiles have played a prominent role in religious ceremonies in many cultures and religions. Priests have worn special vestments and cloths have been used to conceal certain items and enhance the mystery of the occasion. In some cases, the design and use of religious textiles has remained the same for centuries, but others have changed along with the associated traditions. The purpose of the textiles was generally to underline the exalted nature of the ceremony, the mystique of the ritual or the status of a priest.

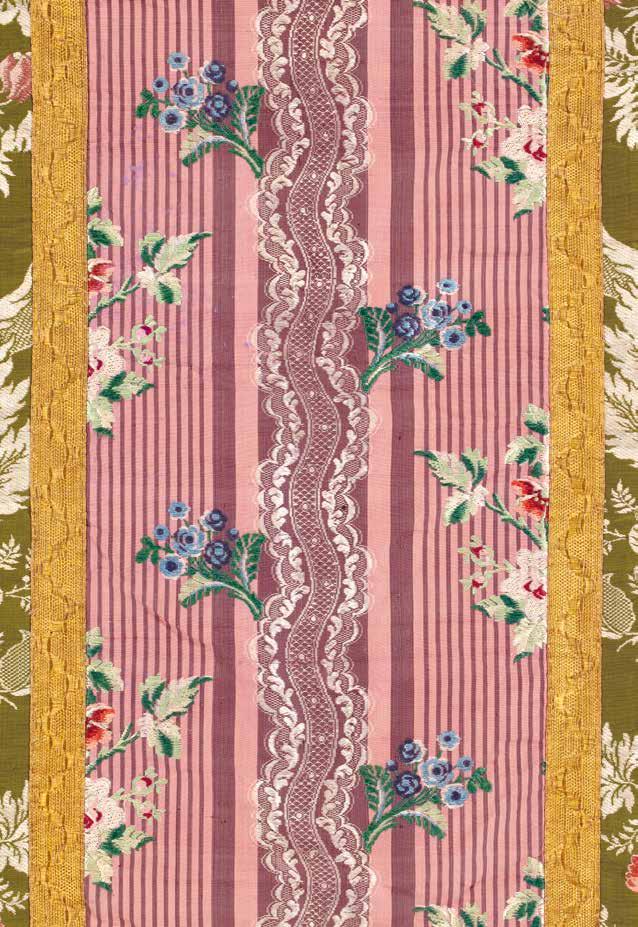

Paramentics dictates the use of textiles in the Catholic church. In the broad sense, paraments are all textile items and vestments that a priest wears or uses at or on the altar during mass and other religious services. The paraments are part of a larger whole, known as the liturgy. Along with other prescribed objects, such as the silver on the altar, and objects that are less subject to certain rules, like painted or sculpted altarpieces, they enhance both the lofty character of the ritual and the viewer’s experience. But less tangible elements such as light, sound and fragrances also play a role in defining rituals.

Paraments in the Catholic church

The paraments that priests still wear during mass originated in garments worn in late antiquity: the priest’s chasuble, the assistant priests’ tunicle and dalmatic, and the cope that a priest would wear during a service without the eucharist. These vestments changed little during the course of the Middle Ages; only the chasuble became slightly narrower. Their shape, colour and decoration were not dictated or regulated at that time, except in the form of centuries of custom and tradition. The more luxurious the material or decoration, the more suitable it was for the special celebrations held during the ecclesiastical year. Many medieval vestments were made of silk and had decorative embroidery in silk, gold and silver thread, often depicting saints or scenes from the Bible. Since the priest stood with his back to the congregation throughout much of the mass, it was on the back of the chasuble that the most decorative elements would be. It was not until the Council of Trent (1545-1563) and the subsequent Roman

Missal of 1570 that centralised orders were issued regarding paraments, under the influence of the CounterReformation. The missal, which for many years defined the standard in the Catholic church, introduced various altar paraments — the chalice veil, the burse and pall — and it also defined the liturgical colours in the Catholic church: white, red, green, purple and black. Carolus Borromeus (1538-1584), Archbishop of Milan, who attended the Council of Trent, explained in his 1577 publication Instructiones Fabricae et Supellectilis Ecclesiasticae that every church should ideally have a full set of paraments in each of the five liturgical colours. These new guidelines introduced changes, and more standardisation. Officially, they remained in force until the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965).

Paraments and identity

As well as honouring God and elevating the ritual, paraments also express identity. During the period of the Dutch Republic (between circa 1588 and 1795), when Catholics were forbidden to openly practise their religion or have church buildings that were visible from the street, their identity came under pressure. The liturgy and the interiors of Catholic churches — of which paraments formed an important part — served to express the church’s identity, using design and iconography to trace a direct line from the Catholic beginning of the church in the Netherlands to the oppressed Catholic church in the Protestant Republic.

This continuous line not only enhanced the unity and solidarity of the Catholic community, it also served as a response to the perceived lack of recognition from Rome. Since the Republic was a Protestant nation, Rome regarded the country as a missionary district where no official Catholic church existed. This felt like a denial of the Catholic structures and congregations that still existed, albeit underground. The quest to define the identity of the Dutch Catholic church led to a schism three hundred years ago. Some Dutch Catholics chose to continue without Rome, electing and consecrating their own archbishop, Cornelis Steenoven, in 1723-1724. This event is also highlighted in the exhibition, illustrated with paraments.