© China Photos/Getty Images; pp27, 142, 144 (top), 250-251, 254 © Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; pp30-31 © MPI/Getty Images; pp34-35 © Bernard Gotfryd/ Getty Images; pp37, 74 from L’Illustration magazine; p38 (top) © The Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society; pp40-41 © Wolfgang Stuppy; p47 © Pepe Franco/Cover/Getty Images; p48 © H. & D. Zielske/LOOK/Getty Images; p49 © Fox Photos/Getty Images; p66 © Ralph Crane/Time Inc./Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; p75 © Yale University Library; p76 (top) © Queens Museum of Art; p88 © MIT Museum; p178 © Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY; p192 © John Edward Linden/arcaidimages.com; p227 © Wolfsonian-Florida International State University and the Wolfson Foundation; pp230-231 © Mark Renders/Getty Images; pp240, 242-243 © Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY; p244 © Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design/The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design; p245 © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource p248 (bottom) © Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg; p249 © Tate, London, 2009; pp258-259 © Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; p262 © The Museum of Modern Art/licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY; pp264, 265 © Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota; p267 © Michael Rougier/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; p268 © National Gallery of Canada

We gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to use these images. Every possible attempt has been made to identify and contact copyright holders. Any errors or omissions are inadvertent and will be corrected in subsequent editions.

(front cover) Brussels 1958: Detail of the Atomium.

(back cover) Paris 1900: The Eiffel Tower and Celestial Globe seen from the River Seine.

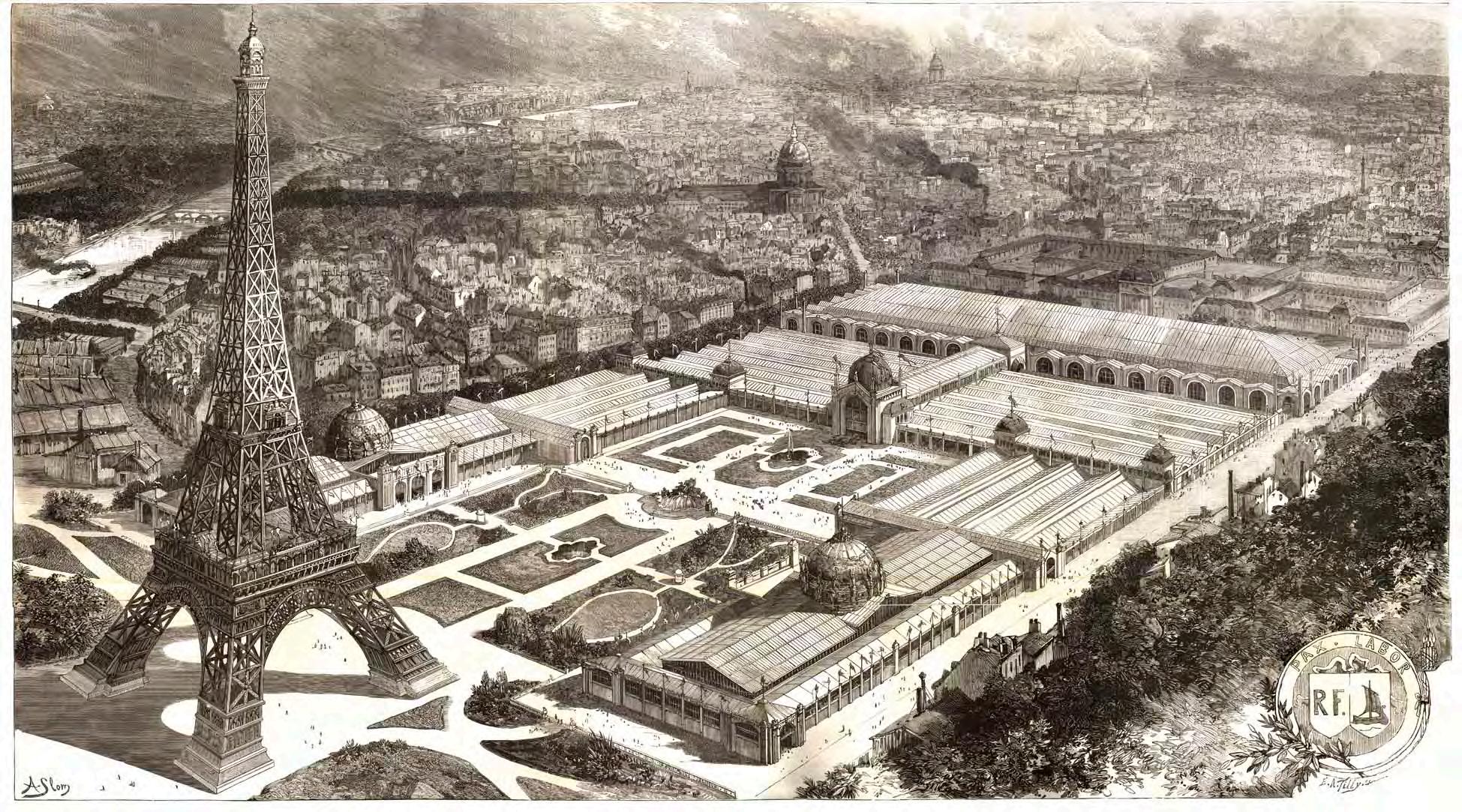

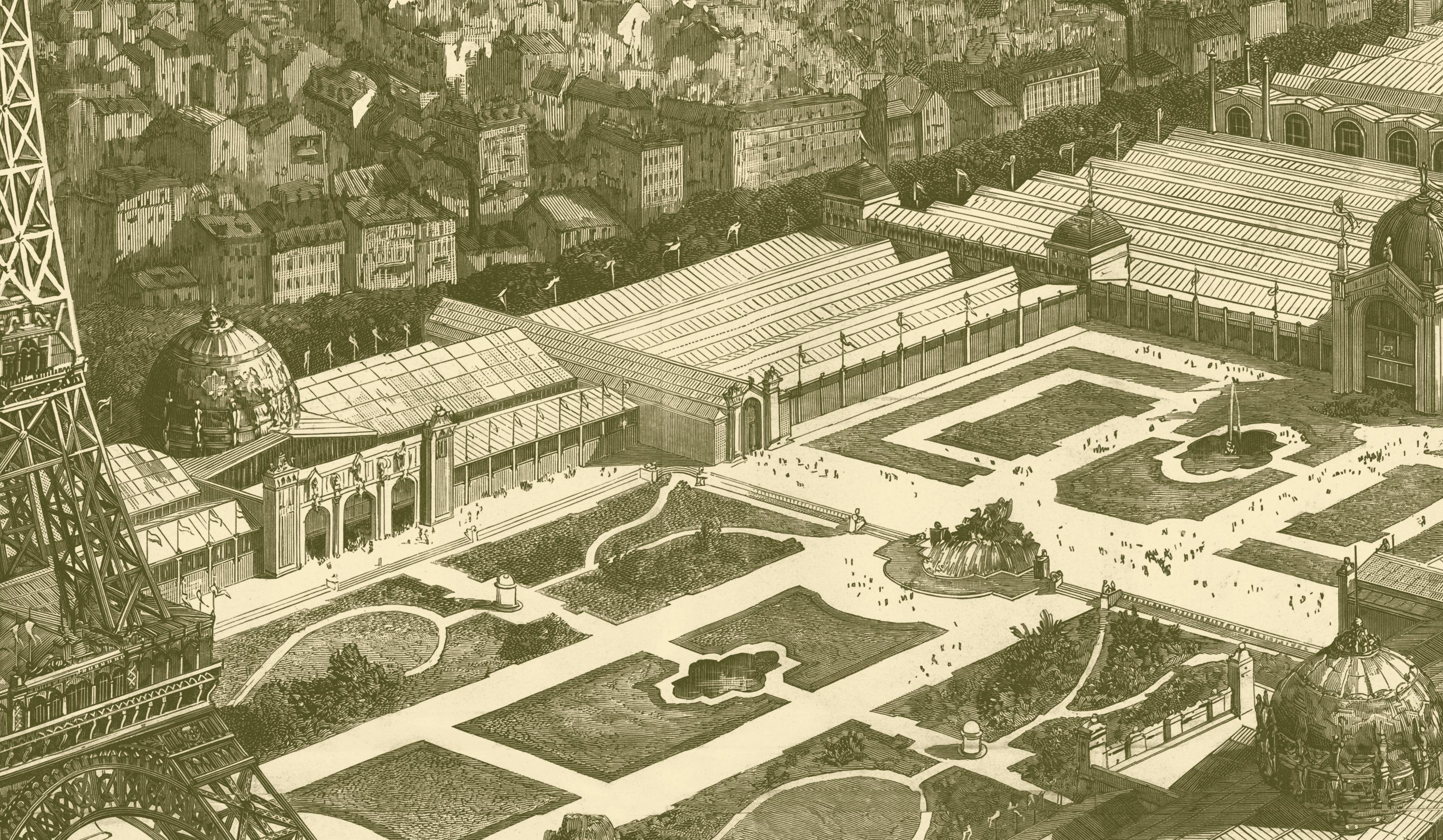

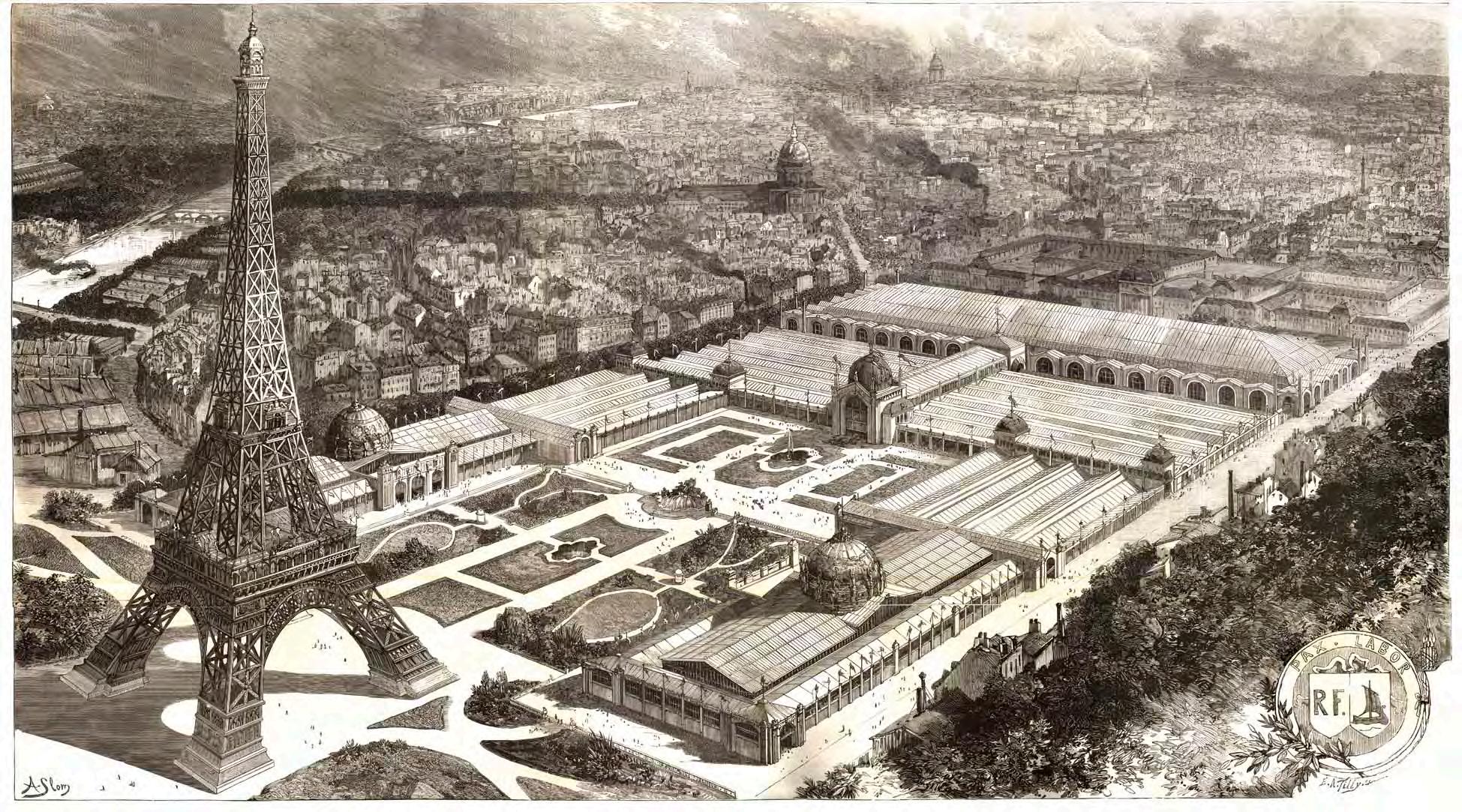

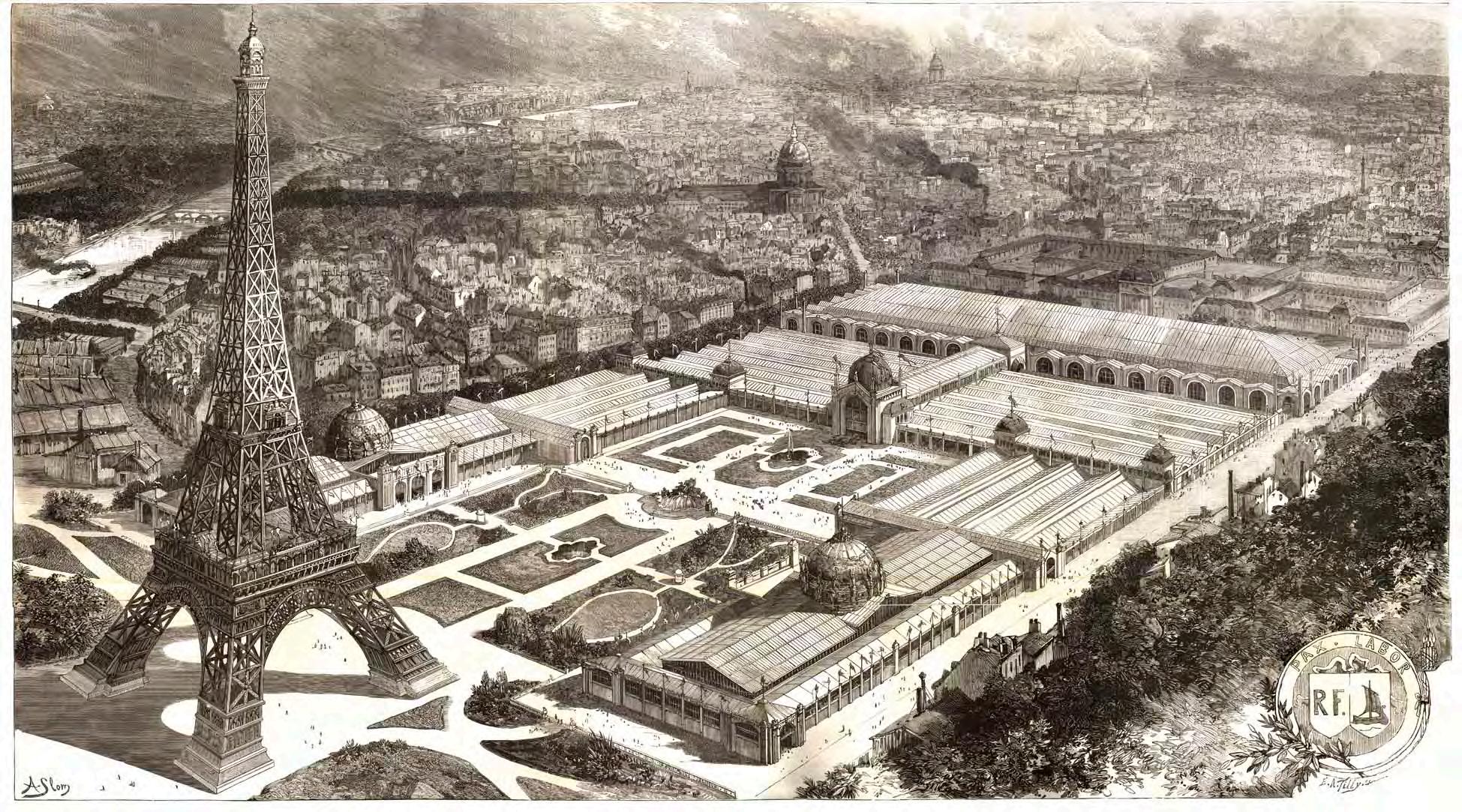

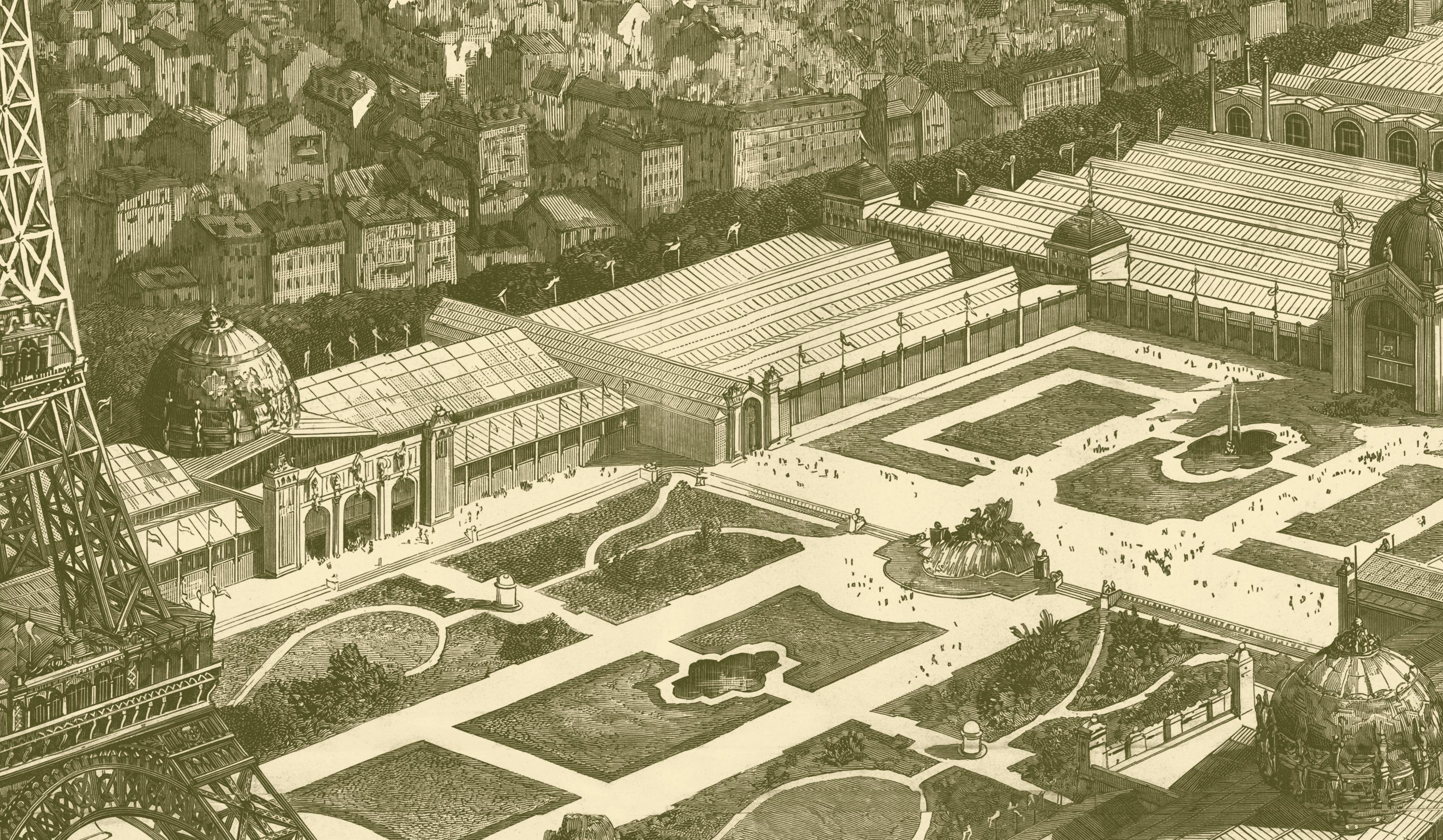

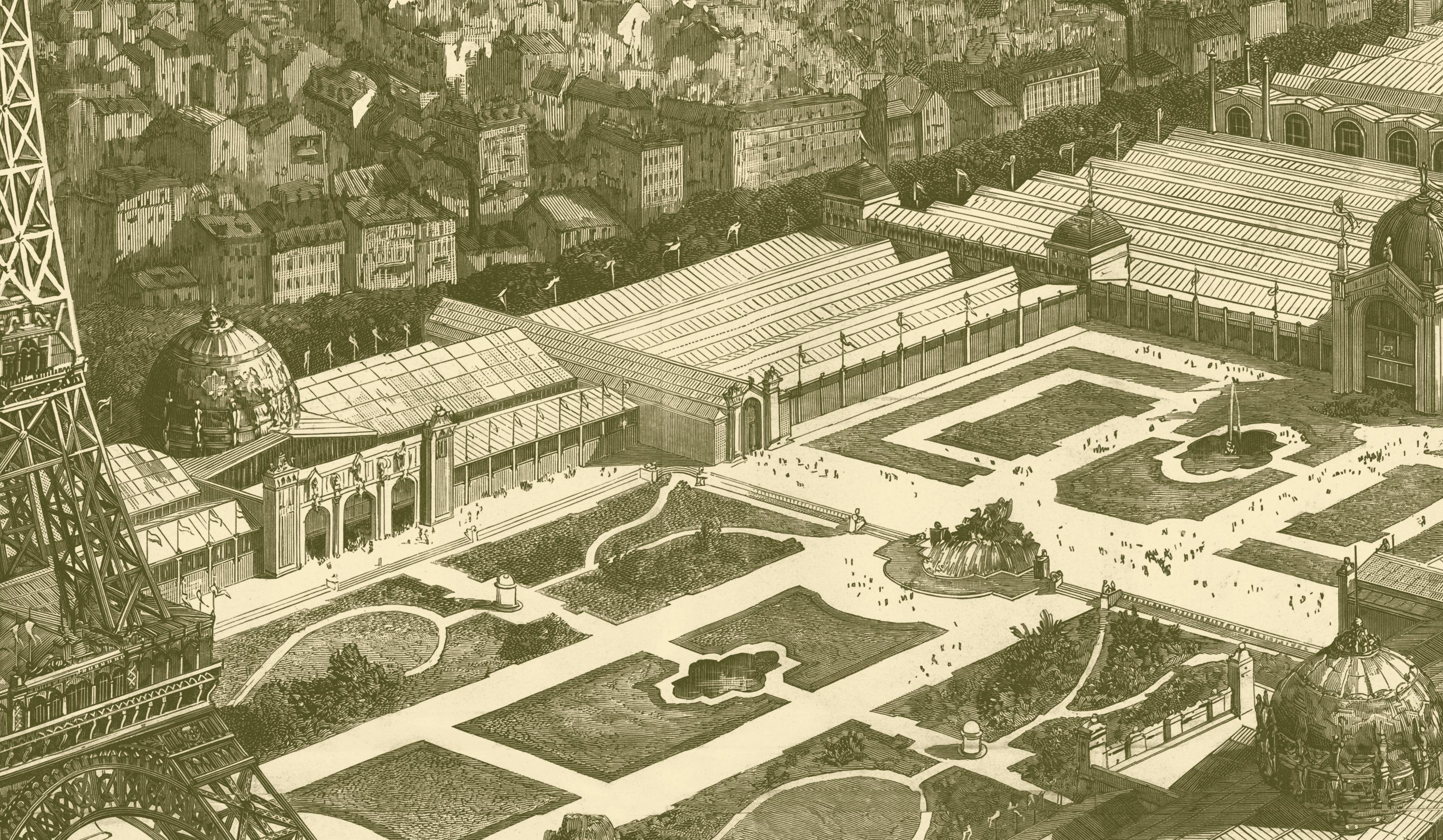

(endpapers) Paris 1889: Detail of a large engraving of the site, showing the Eiffel Tower and the Champ de Mars.

(page 1) New York 1939: The Glass Centre Building.

(page 2) Shanghai 2010: A visitor stands by a display featuring a giant Terracotta Warrior.

(pages 6-7) London 1908: The Court of Honour at the FrancoBritish Exhibition.

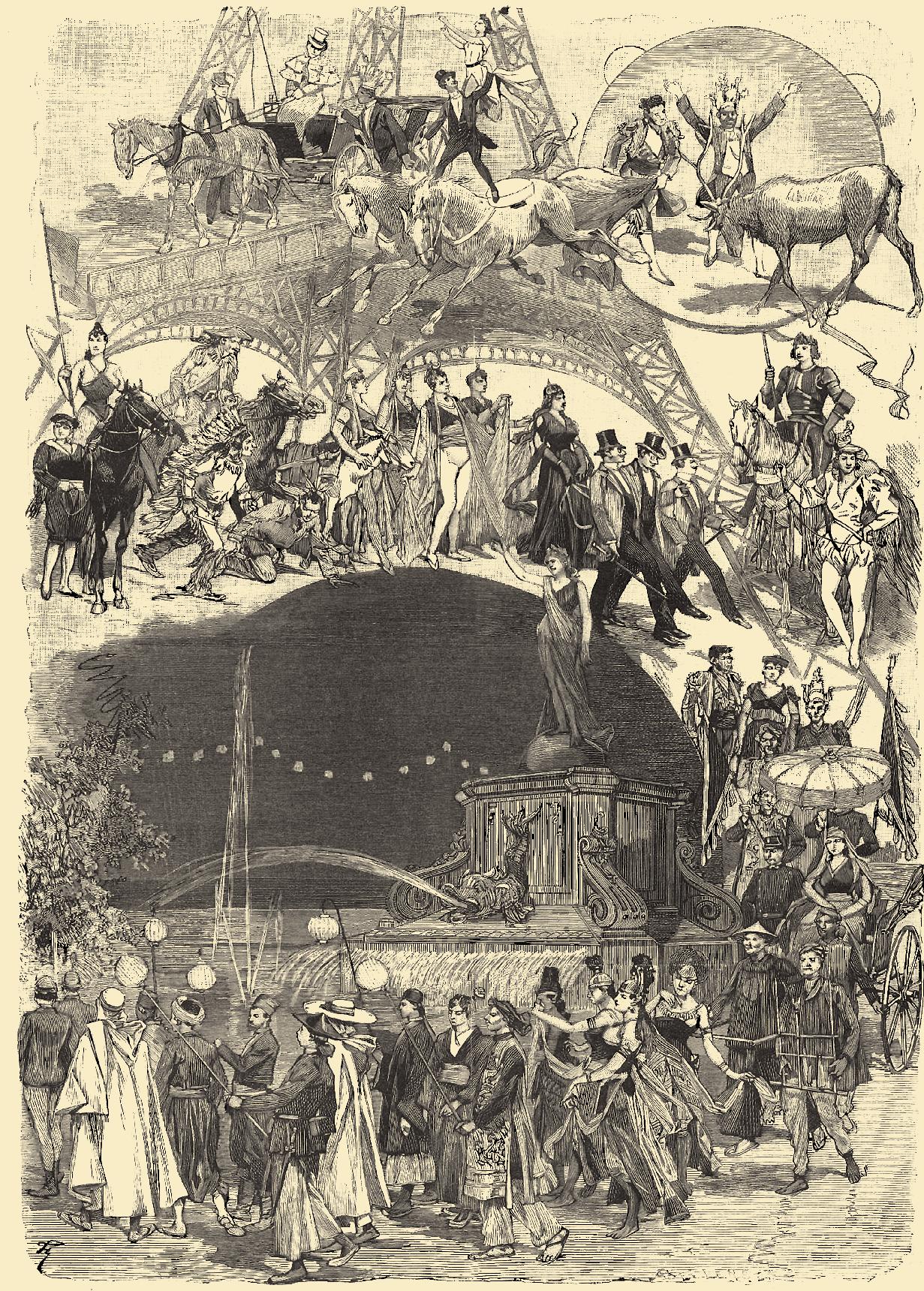

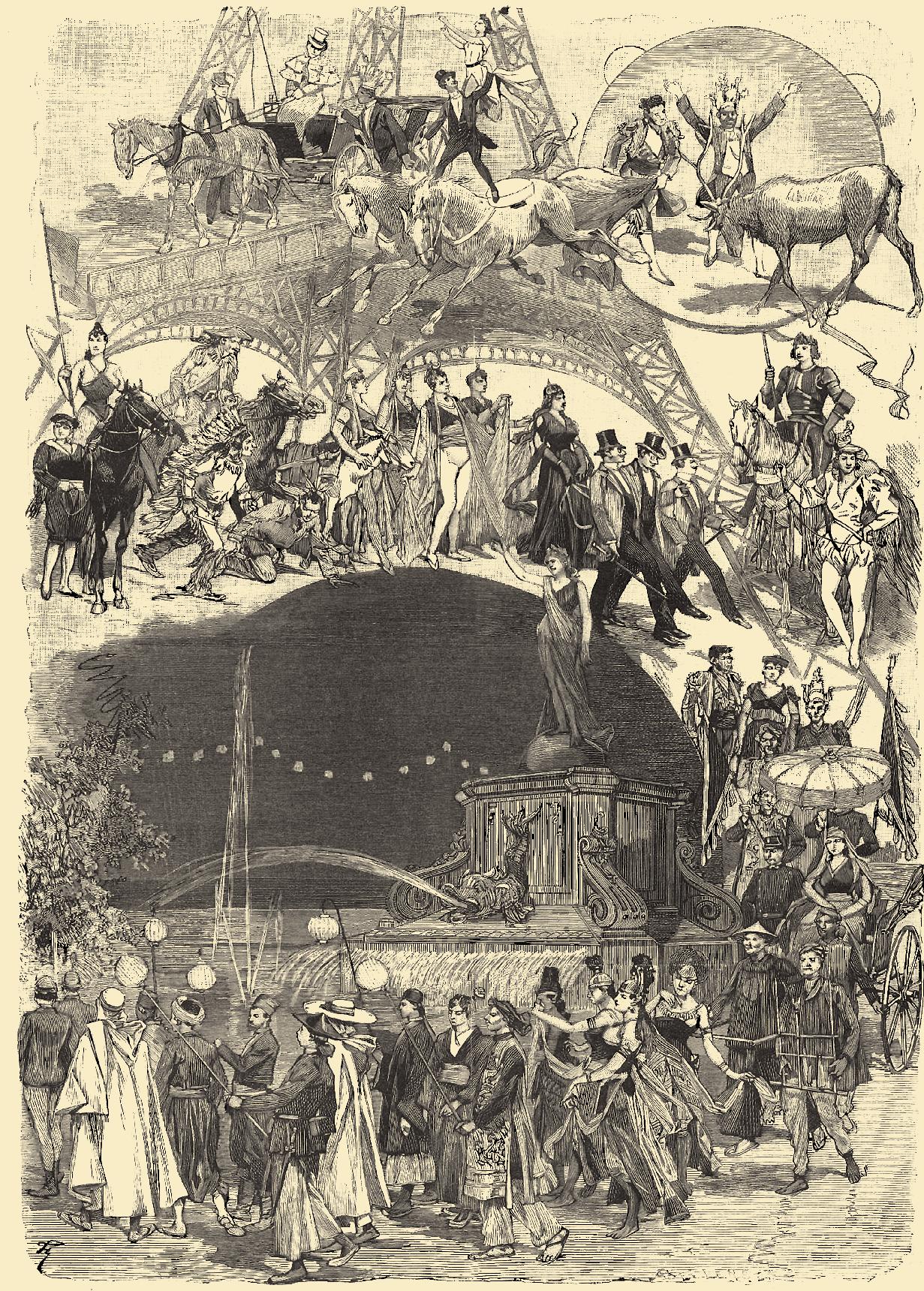

(page 8) Paris 1899: Engraving of an opening parade at the Exposition.

(page 9) Shanghai 2010: The opening parade.

First published in Great

in

Publisher An imprint of New Architecture Group Limited Kimber Studio, Winterbourne,

RG20

UK Tel. +44 (0) 1635 24 88 33

Publisher All rights reserved Paul Greenhalgh hereby asserts his moral rights to be identified as the author of this work. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Publisher. Printed and bound in China A CIP catalogue of this book is available from the British Library All images are © Paul Greenhalgh with the exception of the images listed below and those in the public domain front cover ©

©

Images; p9

For William Greenhalgh (1923-1976) and Marie Joan Greenhalgh (1925-1994) For my brother and sister, and, of course, for Jack and Alex

Britain

2011 by Papadakis

Berkshire,

8AN,

info@papadakis.net www.papadakis.net Publishing Director: Alexandra Papadakis Design Director: Aldo Sampieri Editors: Sarah Roberts, Sheila de Vallée Assistants: Peter Liddle, Caroline Kuhtz, Conni Wong ISBN 978 1 906506 09 4 Copyright © 2011 Paul Greenhalgh and Papadakis

Roger Viollet/Getty Images; p2

Philippe Lopez/AFP/Getty

FairWorld_Prelims 0_AP-as.indd 4-5

c O ntents

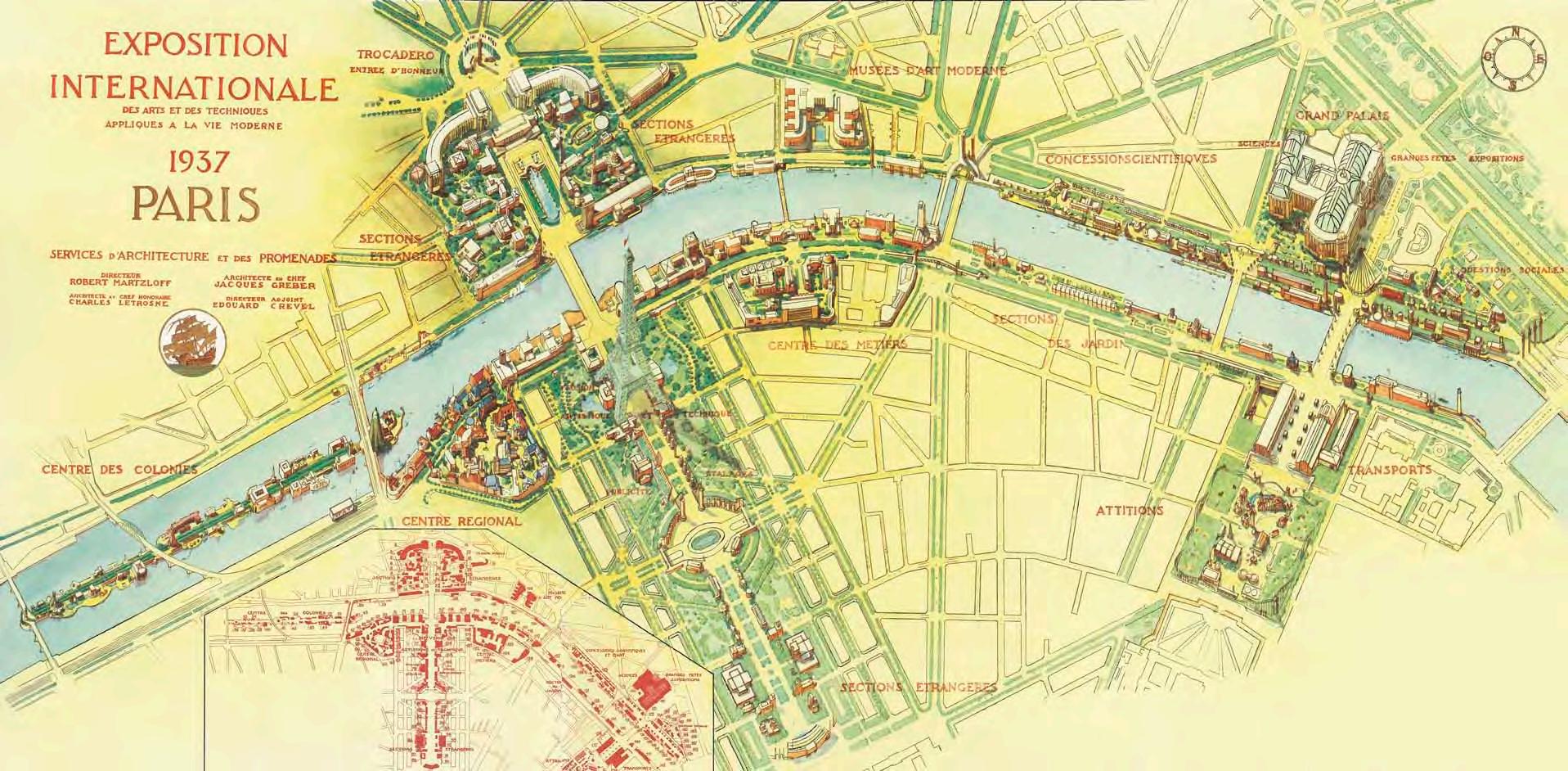

IntRODuctIOn 11 the ORIgIn AnD MeAnIng OF the expOsItIOn MeDIuM 15 Exhibitions before Expos 15 The Formation of the First Expositions 26 Justifying Expositions 32 MOney, pOLItIcs AnD the MAsses 51 Money 51 The British Organisational Model 55 The French Way 58 American Business 62 Cold War Ways and Post-Modern Methods 68 Politics and the Entertaining of the Masses 73 Gender and Display: The Women’s Buildings 84 The Myth and Reality of Profits 92 IMpeRIAL DIspLAy 97 Britain's Exhibitions: Industry and Empire 97 The European Empires on Display 108 Japan’s Imperial Ambition 117 American Expansion 117 huMAn shOWc Ases 123 People as Entertainment 123 Paris and the Growth of the Practice 126 The British Displays 132 Evolutionism and the Peopled Displays 138 The Villages of America 139 Consuming in the Streets of the World 146 Ambassadors on Site 147 nAtIOnAL pROFILe 155 Display and National Identity 155 Frenchness 157 Britain and England 165 America and the Problem of the New 170 Paris in 1937, New York in 1939 176 Pastiche, Boycott, and the Post-War World 185 DesIgnIng An epheMeRAL WORLD 193 Modernity, Design, Expo 193 The Great Exhibition and High Victorian Design 194 Design and the Poor 198 The Example from Outside 201 Architecture and Engineering 202 Historicism and Art Nouveau 213 Art Deco and the Modern Movement 220 Space Age Modern, International Modern, Post-Modern 226 the MeAnIng OF ARt 237 Defining and Displaying the Fine Arts 237 Beaux-Arts and Avant Garde: the French Displays 239 British Art and the Expositions 246 The Growth of American Art 252 Art from Outside: Africa and Oceania 257 After the War 264 pOstscRIpt 271 nOtes 272 InDex 276 AcknOWLeDgeMents 281 bIbLIOgRAphy 282

30/3/11 12:12:36

FairWorld_Prelims 0_AP-as.indd 8-9

30/3/11 12:12:49

FairWorld_book_01_AP_as.indd 18-19

30/3/11 12:14:14

FairWorld_book_02_AP_as.indd 50-51

Money, Politics and the Masses

MONEY

Exhibitions cost an enormous amount of money to stage. Until recently, it was the opinion of many –this author included – that expos of the scale and cost of the grand events before 1970 would not or could not happen now. It seemed no one could afford them, and more importantly, no one seemed to have adequate reason to bother. Surely the purposes expos formerly fulfilled have now been taken care of by various separate media: film, television, the internet, trade fairs, the Olympiads, etc.? Apparently not. In May 2010, the Shanghai city fathers, supported handsomely by the Chinese government, opened the biggest expo site ever constructed, hoping that it would be visited by more people than any of its predecessors.1

The vast sums expended on expositions, and the frequency with which they were held up to 1939, are a testament to the power they were seen to bestow on those involved in their organisation. They were a principal means for government and private enterprise to present their vision of the world to the masses. Because of this, the funding behind them invariably involved political machinations of one kind or another. Those who paid for the exhibitions normally had motives that went well beyond the official literature.

The fairs up to 1914 were saturated with Victorian liberal ideology. The peculiar mixture of free trade, material progress, philanthropy, imperialism and capital that animated the more dramatic decades of the nineteenth century could be found everywhere on exhibition sites. These were the arenas where the grand entrepreneurs could justify, define and congratulate themselves, where imperial free trade could strut in the temporary absence of the profound contradictions it embodied. Thoroughly in the spirit of the first industrial age, the exhibitions illustrated the relation between money and power, and revelled in the belief that the uncontrolled expression of that power was the quintessence of freedom. Philanthropy, one of the humane spin-offs of the industrial system, found its place on exhibition sites, functioning as a conscience to the age. Even here, however, the morality of philanthropy was rarely pure: it was inextricably linked to economic efficiency and expansion. In every way – politically, economically, ideologically and technologically – the fairs were creatures of the modern age, and could not have happened in any other.2

Lorem: ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam nonummy nibh euismod tincidunt ut laoreet dolore magna aliquam erat volutpat. Ut wisi enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exerci tation ullamcorper suscipit lobortis nisl ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis autem vel eum iriure dolor in hendrerit in vulputate velit esse molestie consequat, vel illum dolore eu feugiat nulla facilisis at vero eros et accumsan et iusto odio dignissim qui blandit praesent luptatum zzril delenit augue duis dolore te feugait nulla facilisi.

Lorem: ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam nonummy nibh euismod tincidunt ut laoreet dolore magna aliquam erat volutpat. Ut wisi enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exerci tation ullamcorper suscipit lobortis nisl ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

MONEY, POLITICS AND THE MASSES 51

30/3/11 12:15:42

Shanghai 2010: This computer-generated image of the site presents the ideal view immediately before the Expo opened.

60 FAIR WORLD FairWorld_book_02_AP_as.indd 60-61

MONEY, POLITICS AND THE MASSES 61 30/3/11 12:15:58

70 FAIR WORLD FairWorld_book_02_AP_as.indd 70-71

The world now tends to view Japan through the excellence of its technologically advanced consumer goods. Osaka embodied that vision. The Expo was consciously intended to exemplify the new Japan, which is why government paid for it.

Europe had two expos of some weight and significance after the Second World War: Brussels (1958) and Seville (1992). Both were initiated and heavily funded by government, both national and metropolitan, and both had ambitious agendas for promoting the national profile. The 1958 event was the latest (and last) in a long, proud line of Belgian expos, confirming Belgium as one of the principal expo nations of the modern period. Inevitably, the Expo was host to the Cold War politics that would reappear in major events through to 1970, as America and the USSR strove to outdo one another. More eccentrically, the Belgians themselves used Brussels to celebrate, and perhaps in some instances to apologise for, an odd combination of things. Most prominent among these contrary things were Modernist architecture, nuclear power, and the Belgian Congo. The most significant effect of the Expo was that Brussels was emphasised as the political and organisational centre of Europe. It had become, by housing the European Union, the city from which the continent is run. The Expo gave weight to this role.

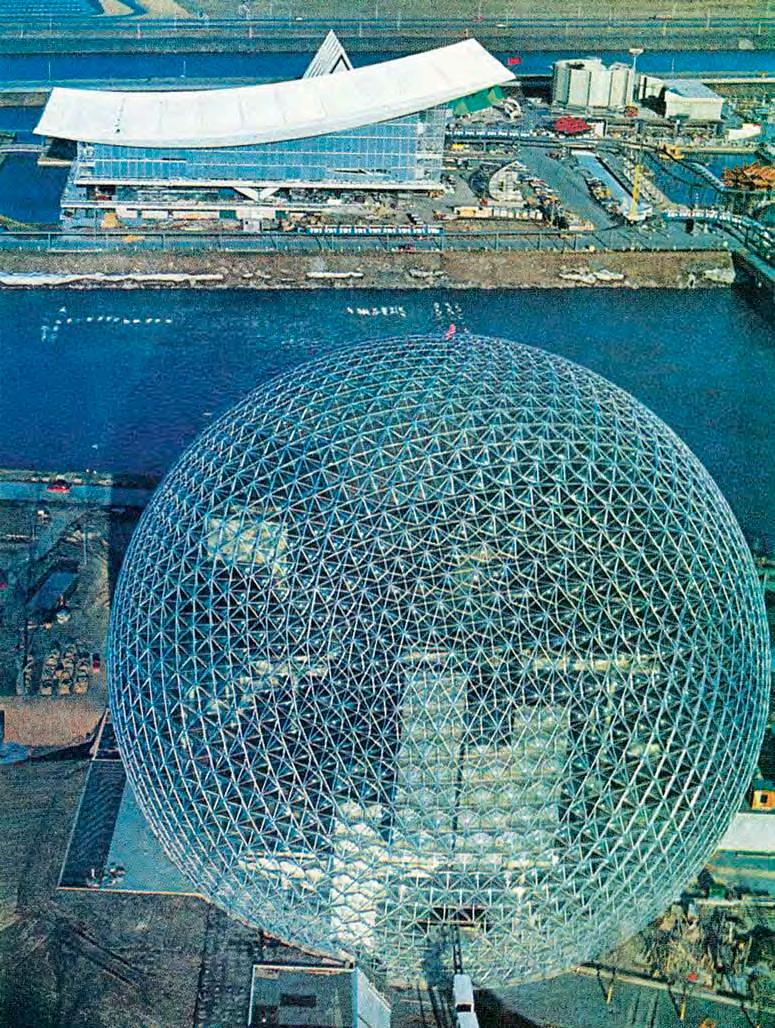

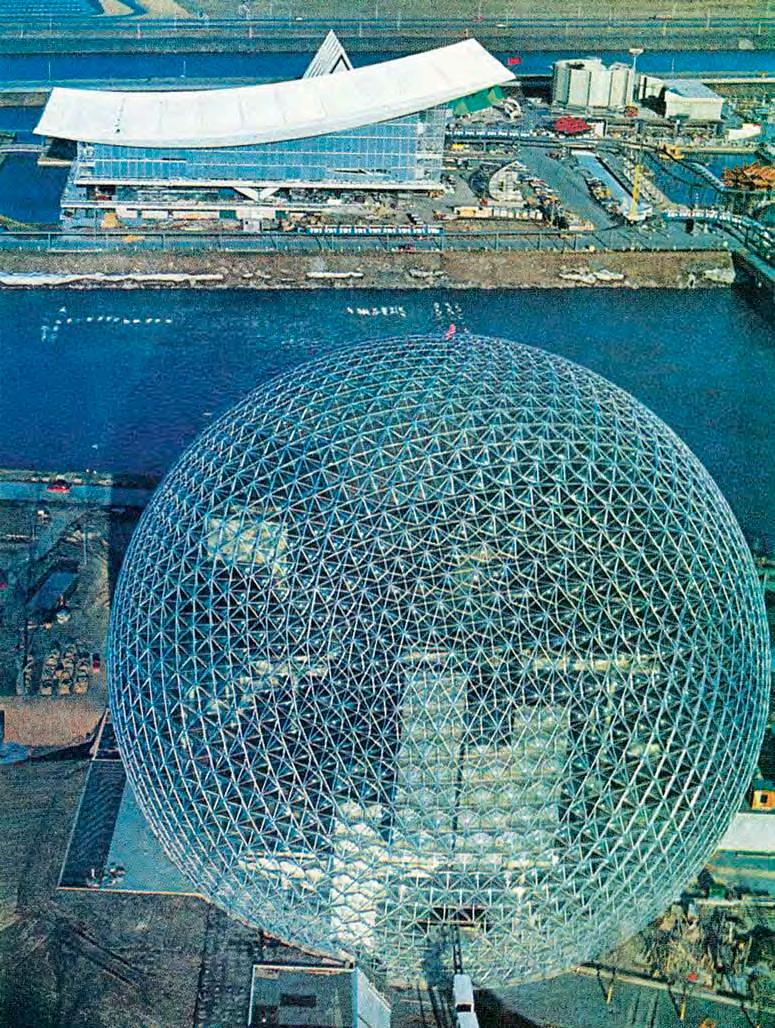

(opposite) Montreal 1967: At the World’s Fairs, design was a weapon used to fight the Cold War. The United States Pavilion in the foreground faces the pavilion of the USSR. The main subjects of propaganda in Montreal were technology, lifestyle, and culture. Courtesy of Life magazine.

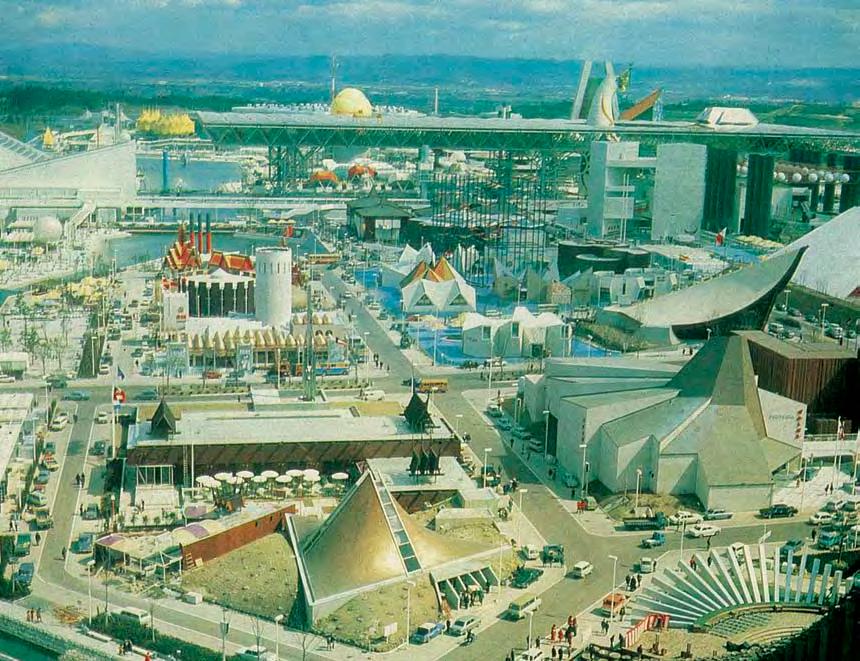

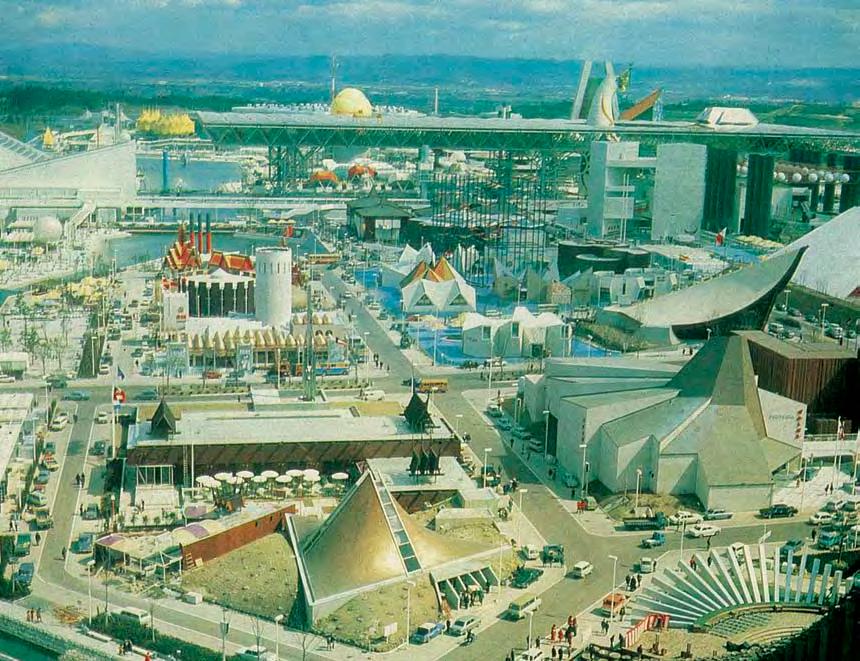

(above) Osaka 1970: A general view of the site.

MONEY, POLITICS AND THE MASSES 71

30/3/11 12:16:12

FairWorld_book_04_as.indd 122-123

Human sHowcases

PEOPlE AS ENtErtAiNMENt

The woman in the postcard stands and stares blankly at the camera that will convert her into a souvenir. Amid the bizarre circus in which she was living in London, she managed to communicate with people, but not well enough to convey who she was or where she came from. She understood that she was a zoological exhibit but she did not fully understand why.

We have normally given a place in history to the expositions because of the range of objects and buildings they assembled on a single site. The historian of art, design, and the decorative arts, for example, cannot afford to exclude them from detailed study on this ground alone, because they brought together disparate types of products in a way that no cultural manifestation could previously contemplate. They reflected and in some important cases led style and taste in their respective times. The focus on objects, however, has detracted from a feature of central importance to the expositions: the displaying of peoples.

The cultural sphere in the Modern period is full of practices that it is difficult to believe existed. Assuredly, this is one of them. Between 1889 and 1939 expositions became human showcases. People from all over the world were brought to sites to be seen by others for their gratification and education. The normal method of display was to create a backdrop in a more or less authentic tableau vivant fashion and put people in it for the duration of the fair. Often, they would build their own accommodation. This was not a performance that they could walk away from. They literally lived on site, surviving and attempting to simulate for besuited visitors what might pass for their daily lives. Between 1890 and 1939, it would be no exaggeration to say that as items on display, objects were seen to be less interesting than human beings, and through the medium of display, human beings were transformed into objects.

When the specific discourses surrounding and justifying this extraordinary genre are scrutinised, they usually reveal an imperial rationale at base. However, this is not always the case, and it is also not the case that these displays were always in some sense immoral. Looking at the exhibitions as a whole,

Lorem: ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam nonummy nibh euismod tincidunt ut laoreet dolore magna aliquam erat volutpat. Ut wisi enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exerci tation ullamcorper suscipit lobortis nisl ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis autem vel eum iriure dolor in hendrerit in vulputate velit esse molestie consequat, vel illum dolore eu feugiat nulla facilisis at vero eros et accumsan et iusto odio dignissim qui blandit praesent luptatum zzril delenit augue duis dolore te feugait nulla facilisi.

Lorem: ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam nonummy nibh euismod tincidunt ut laoreet dolore magna aliquam erat volutpat. Ut wisi enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exerci tation ullamcorper suscipit lobortis nisl ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

London 1910: Image of a woman taken from a postcard titled 'Jajakarn Jalan', indicating that the woman was probably Indonesian. The card was purchased at the London White City and has a postmark of 1910, which means this woman was an exhibit at the Japan-British Exhibition. The message written on the card, by Lily of Clapham Road, London, says "this is a Japanese woman in one of the villages at the White City. She smokes a long pipe and has very black teeth … She gave me this photo of herself, and I gave her a penny". Lily clearly had never seen a Japanese or Indonesian woman before and could not distinguish between the two.

HUMAN SHOWCASES 123

30/3/11 12:19:02

142 FAir

FairWorld_book_04_as.indd 142-143

WOrlD

earliest state of man suggested on one side and primitive nature on the other … the strongest primary colours should be applied here”. Further along “the colours should be more refined and less contrasting, and the Tower, which is to suggest the triumph of man’s achievement, should be the lightest and most delicate in colour”.39 As impressive as the site appears in surviving photographs, they can only begin to describe the actuality of the scene. Thus pure colour was natural, simple and brutal; mixed colour, particularly pastel shades, was synthetic, complex and hence civilised. Put bluntly, red and yellow were less civilised than pink and beige. Virtually nowhere else in the history of architecture or design was there a more carefully constructed contrivance with the specific aim of highlighting differences between racial types. The Buffalo Fair, and many which followed it, had an ideological apartheid underpinning it, reinforcing the racial structure of American society by driving wedges between the various ethnic groups.

In this sense, America had an additional problem. At virtually all of the World’s Fairs up to the Second World War, it experienced racial tensions of a kind that were still insignificant in Europe, caused by indigenous populations of coloured peoples. These tensions were not reduced by an insistence on

(opposite) Texas 1936: Into Bondage, oil on canvas, by Aaron Douglas is an icon of African-American modern art. It was one of a group of murals, of which two survive. Courtesy of the Corcoran Gallery of Art.

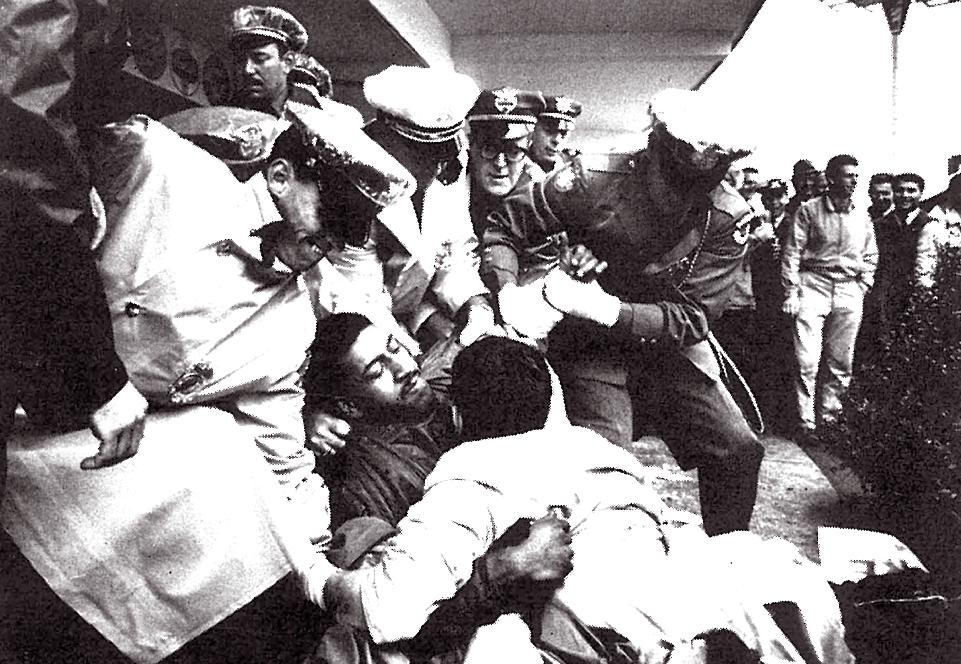

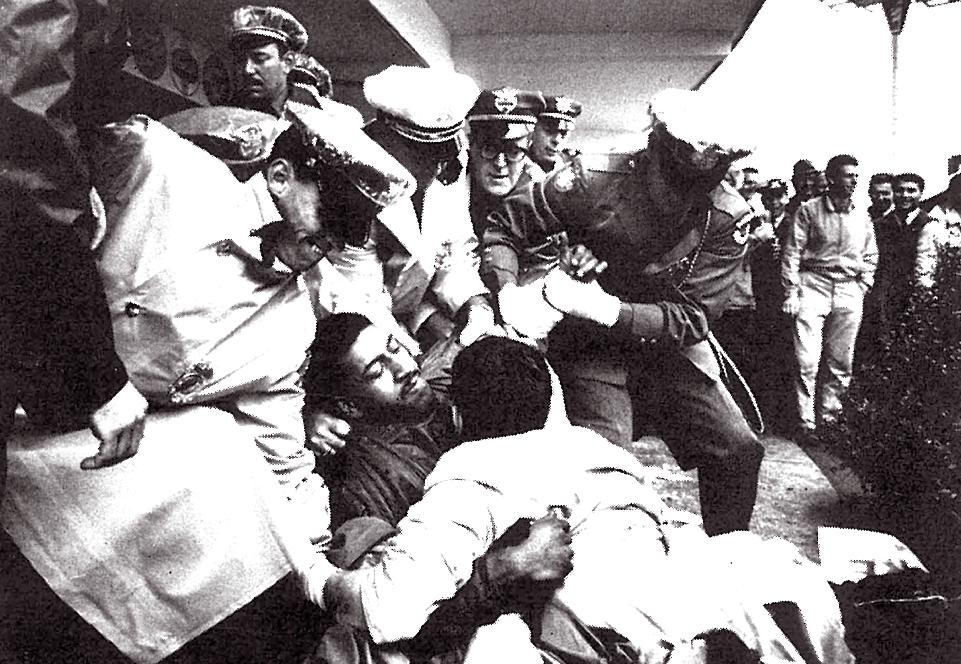

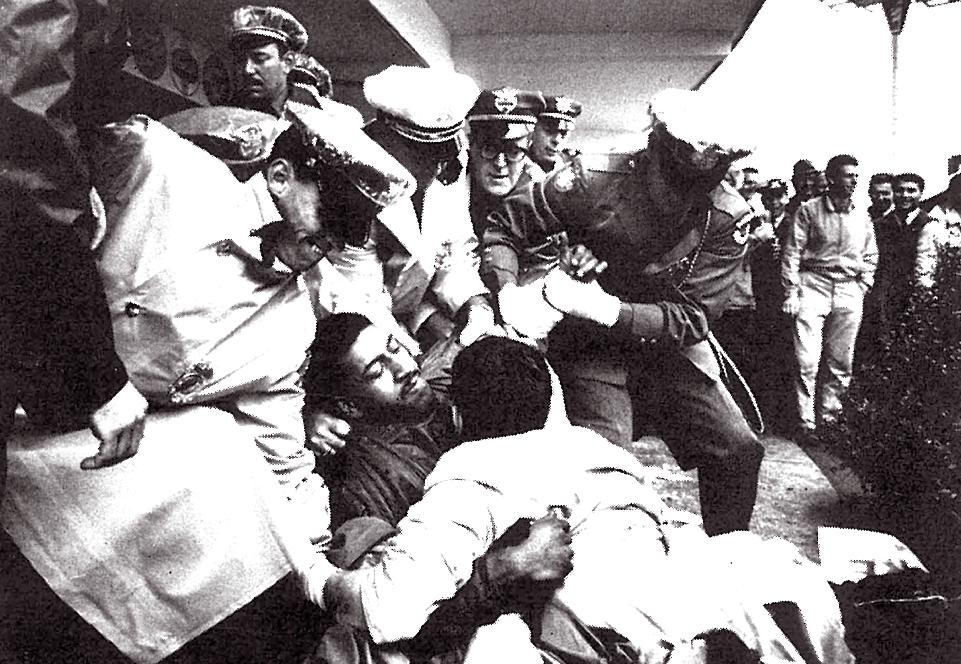

(below) New York 1964: The Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) staged a protest during the opening ceremonies of the New York Fair. This was aggressively dispersed by the police and several of CORE’s leaders were arrested. Courtesy of Life Magazine.

SHOWCASES 143

HUMAN

30/3/11 12:19:23

158 FAIR WORLD

FairWorld_book_05_as.indd 158-159

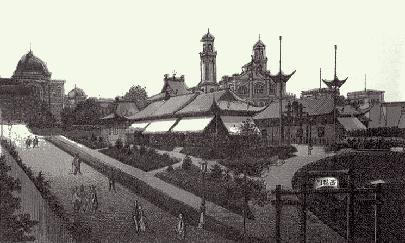

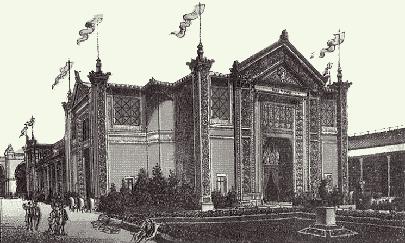

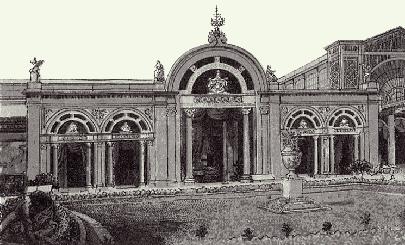

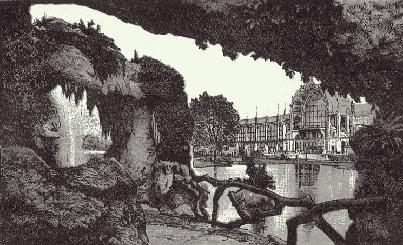

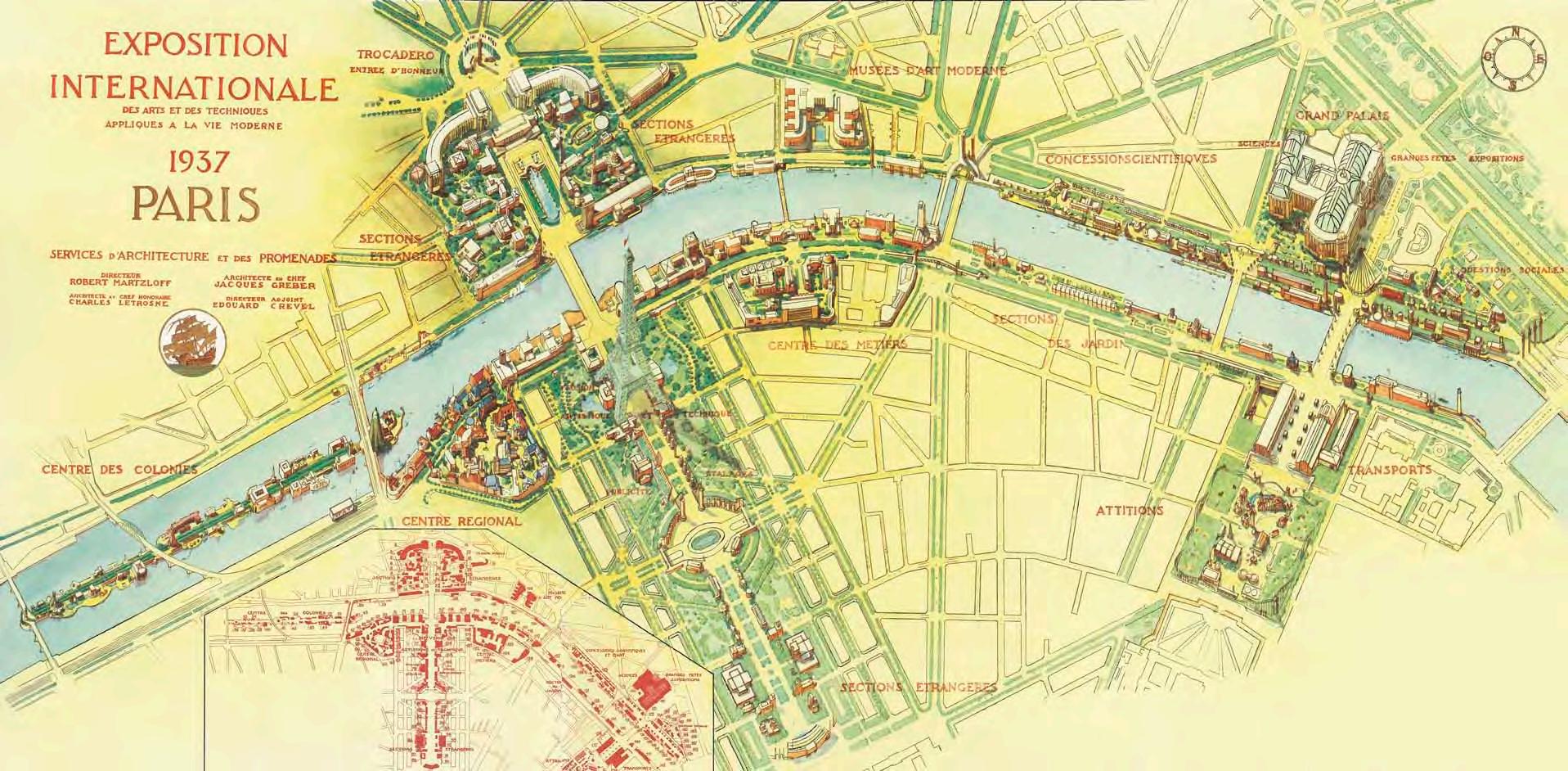

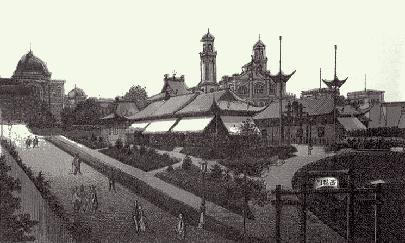

Paris 1878: The main pavilions of the Exposition of 1878, taken from an early example of the tourist souvenir guide, the cover of which is shown here (right). The pavilions shown (top left to bottom right) are the Palais du Trocadéro, the Machine Halls, the Chinese Pavilion, the Japanese Pavilion, the Palace of Fine Arts, the Ville de Paris building, the Italian Pavilion, the Austrian Pavilion and the Grotto at the principal entrance.

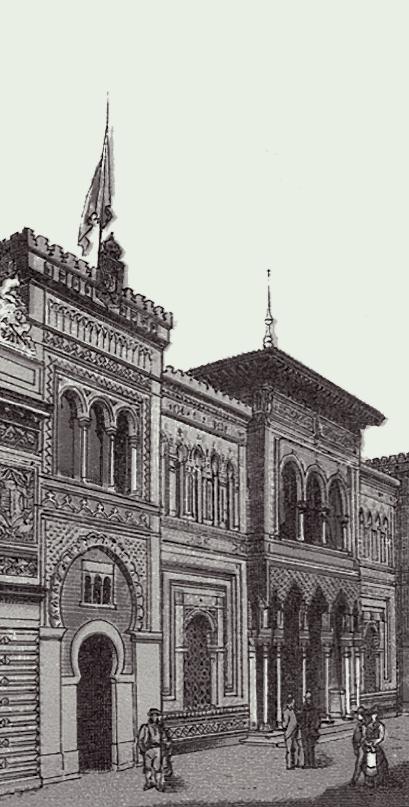

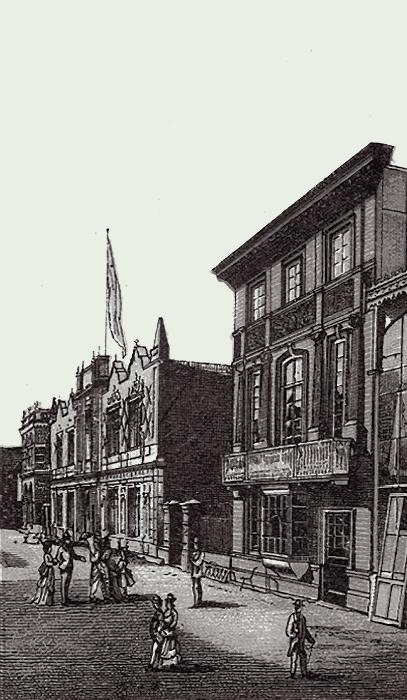

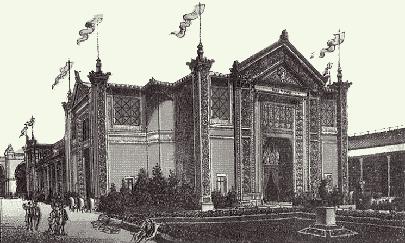

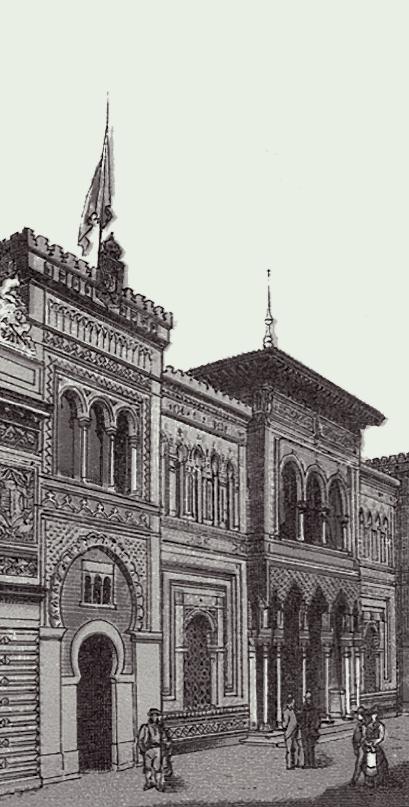

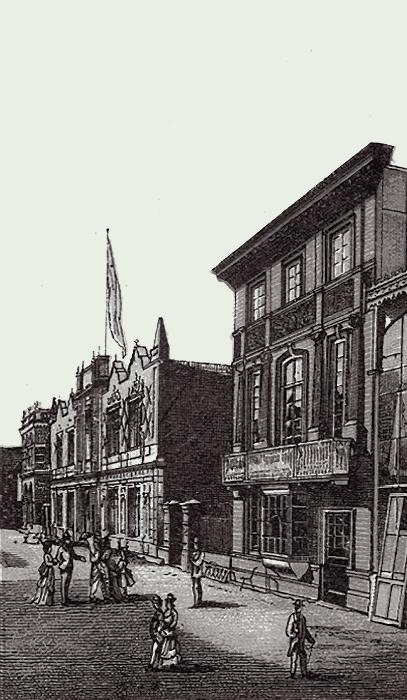

(top left to bottom right ) Paris 1878: The Spanish Pavilion, the Norwegian Pavilion, the English House, the S è vres manufactures display and the English Pavilion.

(overleaf ) Paris 1878: The Trocadéro Building was the centrepiece of the Exposition and a core element in all the Paris expositions up until 1937 when it was demolished to make way for the Palais de Chaillot.

NATIONAL PROFILE 159 30/3/11 12:20:20

178 FAIR WORLD

FairWorld_book_05_as.indd 178-179

Paris 1937: Guernica, by Pablo Picasso, is one of the most important artistic statements on war in the twentieth century and undoubtedly the single most important work of art made specifically for an exposition. Picasso’s masterpiece has the powerful sense of being a public mural, made to be observed by a mass audience in a fundamentally public setting.

NATIONAL PROFILE 179 30/3/11 12:20:48

250 FAIR WORlD FairWorld_book_07_as.indd 250-251

THE

MEANING OF ART 251

Paris 1867: Niagara, 1857, oil on canvas, by Frederic Church. This view of Niagara Falls became one of the best known American paintings of the nineteenth century and assured Church’s reputation as a leading artist in the new country.

30/3/11 12:23:26

Courtesy of the Corcoran Gallery of Art.

FairWorld_book_Endpapers_as.indd 272-273

30/3/11 12:11:56