the architects themselves choose to use unusual analogies to describe their highly structured, seemingly randomly formed architectural volumes – derived, for instance, from geology – this in fact only concerns the side facing the railway tracks. Facing the street, the buildings are staged calmly and almost conventionally. Here they indeed act as part of the fabric, completing it with a seam towards the railway tracks. The splicing with the urban fabric is normal and conventional. The boundary, on the other hand, is specific and unique.4

A NON-OBTRUSIVE BEAUTY

That architecture is a backdrop is a claim by Hermann Czech5 that Esch Sintzel like to refer to (see the essay by Ákos Moravánszky, p. 321). Taken at face value, the statement is not without its pitfalls. Quite apart from the fact that it conceals the reality that monuments can perhaps attract attention for good reasons, it could also easily be misunderstood as an invitation to flirt with banality, to generally damn the extraordinary or even to excuse the sloppiness of the mainstream. But this statement cannot be reversed (and Czech naturally never claimed that it could be). Regarding a possible architecture of the tessuto, what is in fact decisive is that background alone by no means automatically constitutes architecture. Nonetheless, a phenomenon becomes apparent when experiencing historic cities (not even necessarily in Italy!), for instance drinking a coffee on a square ringed by a variety of buildings. Somewhat weary, one pays little attention to most of them. They form the urban surroundings, the backdrop to life (to use Czech’s expression). They are part of the fabric. But suddenly, casting an idle glance around, perhaps one’s gaze becomes fixed. One recognises, for instance, an attractive entrance, and then notices that it’s part of a well-composed facade. It is probably a déformation professionelle if one then goes on to ask oneself how the composition works and what makes it appealing, beginning to speculate

about proportions and admiring the elegance of the profile. Nonetheless, all of us with an affinity for architecture undoubtedly know the occasional feeling of being struck by a sudden gleam of quality – or, to console ourselves, beauty – breaking through one’s general sense of distraction.

Czech says that architecture should only speak when asked.6 In this case, however, the reverse is also true. Architecture, if it claims to be such, has to be able to withstand a second and also a third glance, and then begin to speak.7 Even if it primarily presents itself as background and a part of the urban fabric, the more closely one looks at it, the more qualities it reveals, only then to unfurl a delightful richness. Like this, it finds its place in the imaginary Museum of Architectures, albeit not by virtue of its conspicuousness or its model character, but rather based on its quality. This lies, not least, in the richness of architecture and the adoption and interpretation of the typical in a perhaps cautious yet characteristic manner.

It is precisely this sort of beauty that pervades the Zollstrasse buildings, and indeed is characteristic of all of Esch Sintzel’s architecture. How the protrusion of the triangular bay windows in the calm street-front facade initiates the animated railway frontage and at the same time acts as an adaptation of the cut-off corners typical for the neighbourhood; how the regular order of the columns is enlivened by variations; how finely calibrated the mediation is between large and small – from the colossal order of the columns to the texture of the parapet railings; how harmoniously the horizontality and verticality in the relief of the infills interact; and how, in all of this, the residential variety is made apparent without becoming domineering. All of this (and much more besides) is namely there but is not obtrusive.

IMPROVING THE CONTEXT

It goes without saying that an architecture of the tessuto must be contextual. In the work of an office, the range of sites leads, perforce,

the architects themselves choose to use unusual analogies to describe their highly structured, seemingly randomly formed architectural volumes – derived, for instance, from geology – this in fact only concerns the side facing the railway tracks. Facing the street, the buildings are staged calmly and almost conventionally. Here they indeed act as part of the fabric, completing it with a seam towards the railway tracks. The splicing with the urban fabric is normal and conventional. The boundary, on the other hand, is specific and unique.4

A NON-OBTRUSIVE BEAUTY

That architecture is a backdrop is a claim by Hermann Czech5 that Esch Sintzel like to refer to (see the essay by Ákos Moravánszky, p. 321). Taken at face value, the statement is not without its pitfalls. Quite apart from the fact that it conceals the reality that monuments can perhaps attract attention for good reasons, it could also easily be misunderstood as an invitation to flirt with banality, to generally damn the extraordinary or even to excuse the sloppiness of the mainstream. But this statement cannot be reversed (and Czech naturally never claimed that it could be). Regarding a possible architecture of the tessuto, what is in fact decisive is that background alone by no means automatically constitutes architecture. Nonetheless, a phenomenon becomes apparent when experiencing historic cities (not even necessarily in Italy!), for instance drinking a coffee on a square ringed by a variety of buildings. Somewhat weary, one pays little attention to most of them. They form the urban surroundings, the backdrop to life (to use Czech’s expression). They are part of the fabric. But suddenly, casting an idle glance around, perhaps one’s gaze becomes fixed. One recognises, for instance, an attractive entrance, and then notices that it’s part of a well-composed facade. It is probably a déformation professionelle if one then goes on to ask oneself how the composition works and what makes it appealing, beginning to speculate

about proportions and admiring the elegance of the profile. Nonetheless, all of us with an affinity for architecture undoubtedly know the occasional feeling of being struck by a sudden gleam of quality – or, to console ourselves, beauty – breaking through one’s general sense of distraction.

Czech says that architecture should only speak when asked.6 In this case, however, the reverse is also true. Architecture, if it claims to be such, has to be able to withstand a second and also a third glance, and then begin to speak.7 Even if it primarily presents itself as background and a part of the urban fabric, the more closely one looks at it, the more qualities it reveals, only then to unfurl a delightful richness. Like this, it finds its place in the imaginary Museum of Architectures, albeit not by virtue of its conspicuousness or its model character, but rather based on its quality. This lies, not least, in the richness of architecture and the adoption and interpretation of the typical in a perhaps cautious yet characteristic manner.

It is precisely this sort of beauty that pervades the Zollstrasse buildings, and indeed is characteristic of all of Esch Sintzel’s architecture. How the protrusion of the triangular bay windows in the calm street-front facade initiates the animated railway frontage and at the same time acts as an adaptation of the cut-off corners typical for the neighbourhood; how the regular order of the columns is enlivened by variations; how finely calibrated the mediation is between large and small – from the colossal order of the columns to the texture of the parapet railings; how harmoniously the horizontality and verticality in the relief of the infills interact; and how, in all of this, the residential variety is made apparent without becoming domineering. All of this (and much more besides) is namely there but is not obtrusive.

IMPROVING THE CONTEXT

It goes without saying that an architecture of the tessuto must be contextual. In the work of an office, the range of sites leads, perforce,

the wall. Finally, the complementary clampings of the window ledge and the skirting board integrate the window niche and the facade wall into the shape of the room.

Here the constructional configuration of the wall therefore provides welcome scope to design the wall relief, with the help of ledges and boards, as a dovetailing of layers that spatially relate the room with the outside – and this in a far more pronounced fashion than the window openings alone would allow. Whereas inside the room emphasis is put on the horizontality that the columns impart to the progression of the chromatically homogenous walls, the design of the exterior facade stresses the verticality, in keeping with the standing nature of the building. God forbid, therefore, that anyone could imagine that the arrangement of the wall literally depicts its constructional structure!

Ultimately, the choice of materials and building methods also has to do with the whole: solid and worthy materials, but by no means a material fetishism; practicality and flexible scope, but by no means social sculpture; sustainability, of course, but by no means ecological architecture. The list is endless. This commitment to “the difficult whole” 10 may seem self-evident, but the recent past has shown how tempting it is to conceptualise solitary aspects of architecture and to then subordinate everything else to them. This has resulted in innumerable spectacular and innovative buildings, but their one-sidedness has rarely made them durable. The fear is that this also applies to those who now fully subscribe to the currently prominent topics of energy efficiency and net zero. Real sustainability, however, is only achievable if we take it seriously in its entire circumference. It’s about the whole that architecture – if we believe the ancients – has always wanted to be. That individual factors have to be constantly reappraised is obvious. A double-skinned brick wall coursing like in Brunnmatt in Bern would no longer be a solution today, and even columned architecture like in Zollstrasse in Zurich would probably now cause heated debates.

THE PRIVATE AND THE PUBLIC

Threshold spaces, with their double or multiple identities between the city and the building, public and private, or inside and outside, play an important role in the work of Esch Sintzel. They are part of their stance to combine as many elements and aspects of architecture as possible and to integrate them together in terms of their dependencies. This may well be an echo of Philipp Esch’s experience as a trainee with Herman Hertzberger or Stephan Sintzel’s as an apprentice with Rolf Keller: for both of them the design of transitional spaces is one of the key tasks in architecture, as also demanded by their master Aldo von Eyck.

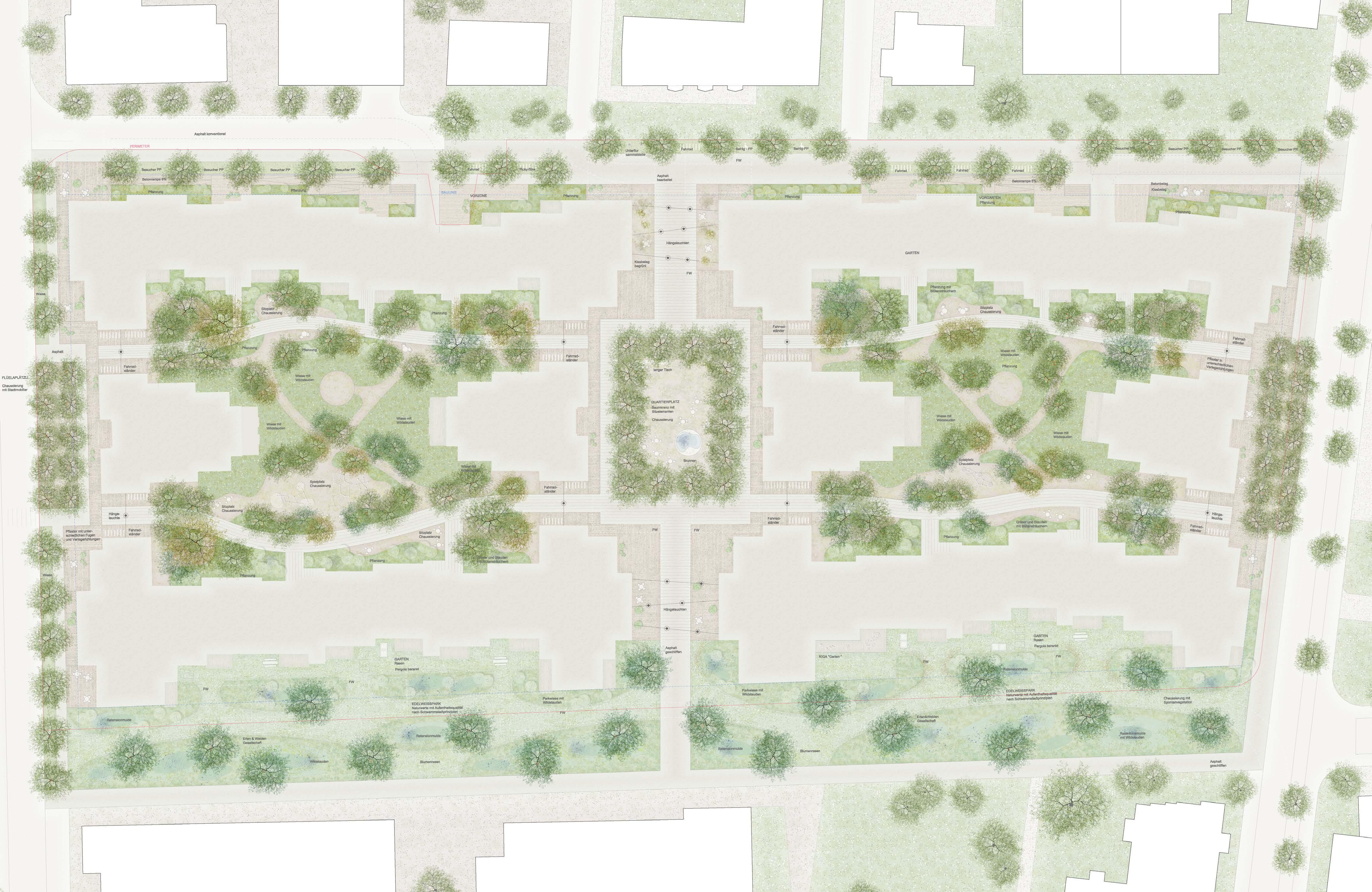

Threshold spaces shield the private and the public to an equal degree, at the same time opening up scope for social interaction. The porches in the Kuppe project on the Trift in Horgen and in the courtyard in Maiengasse in Basel are spaces like these, but similarly the expansive entrance halls and the freely accessible garden courtyard in Brunnmatt in Bern, or the central entrance and the inner streetways in the former wine warehouse in Basel. The list could go on, but all of their projects have similar spaces that oscillate between public and private, often even at different scales. Even the planned building with miniature apartments at the exposed trainstation site in Winterthur has generous, interconnected stairway halls, laundry rooms and working spaces that are accessible to all the residents.

In the last resort, Esch Sintzel give the claims of the city priority over those of the individual apartments, even outside the city centres. This is the significant discovery that emerged from the lengthy design process for the Oberzelg residential scheme in Winterthur Sennhof (see pp. 96–113 ). This project makes it particularly clear to what extent urban development and apartments are interrelated. The beneficiary of this is not only the urban environment but equally the residents. A good apartment is one that is well-situated – a pithy statement by Michael Alder that those in

ATTIKAGESCHOSS/TOP FLOOR

anlage Brunnmatt-Ost, Bern

QUERSCHNITT/CROSS SECTION

QUERSCHNITT/CROSS SECTION

LÄNGSSCHNITT/LONGITUDINAL SECTION

Querschnitt A 1:500

ERDGESCHOSS/GROUND FLOOR