A conversation

A conversation on libraries, books and Jewish history, between Shmuel Feiner, Emile Schrijver and Yigal Zalmona

This exhibition and its accompanying catalogue are presented in the form of a conversation between the National Library of Israel and one of the leading private Jewish libraries, the Braginsky Collection. Here, its two curators engage in their own conversation with Prof. Shmuel Feiner of Ramat Gan’s Bar-Ilan University, chairman of the Historical Society of Israel. Feiner’s latest publication is The Jewish Eighteenth Century: A European Biography, 1700–1750, which appeared in Hebrew in 2017 and in English in 2020. A second volume, covering the years 1750–1800, appeared in Hebrew in 2021. An English edition is anticipated in 2023. The conversation deals mainly with the Early Modern period. That time of enormous transition in European Jewish history is amply represented in the rich holdings of both the National Library of Israel and the Braginsky Collection. Their exchange of ideas presents a historical and intellectual context in which to understand the superb Early Modern manuscripts featured in this exhibition and its accompanying catalogue.

Shmuel Feiner I would like to say a few words from the perspective of a historian working on early modernization and secularization. What I try to do in my studies is listen to the conflicts and the tensions in this period. The eighteenth century, but also the nineteenth, was a period of transition, especially in Eastern Europe. From the perspective of the history of the book, one might argue that my subject is the secularization of the book, of the Jewish book, not just the Hebrew book. Modernization and secularization have presented a great challenge. They still do. They present a challenge to the Jewish people: its culture, public sphere, politics, religious thought and practice. When it comes to books, I’m always amazed to see the power of the Jewish book in this process: how the book influences modernization in general and secularization in particular. There’s an interesting example that I would like to share with you.

When I was working on the early Haskalah, I was struck by the desire and passion of young Jewish men – some were still in the yeshiva, others had already left the yeshiva – the passion for foreign knowledge, yeda hitsoni, hokhmot hitsoniyot. Those terms served as code for everything outside the framework of Torah, Talmud, and

halakha, but also “forbidden” subjects, especially in Ashkenazi culture, as you know. In the library at Harvard University, I found a small textbook, written by a Jewish student. He was a medical student at the university of Frankfurt am Oder. In 1722, he published this book, only a few copies of which still exist, titled Mafteah ha-algebra ha-hadashah, “A Key to the New Algebra.” Well, I’ve never been interested in algebra, not even at school. What makes this so fascinating is the introduction. The author is Asher Anshel Worms, and the introduction is a literary masterpiece.

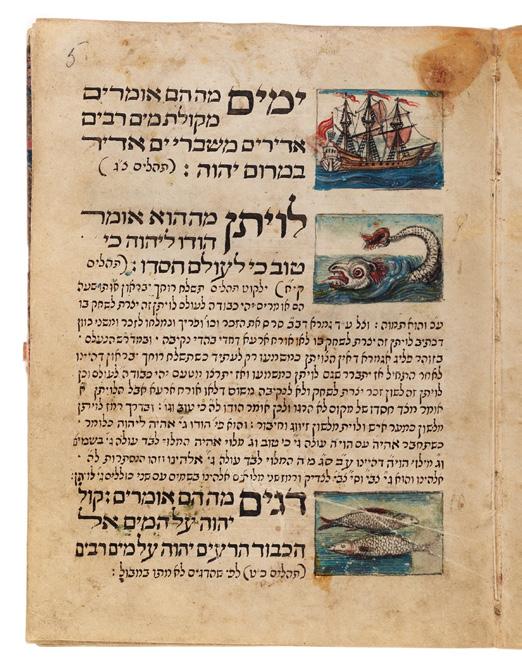

The author is describing a dream: he depicts himself sitting on the top of a hill, on a desert island, looking at the ocean. In the distance, he sees a ship in distress. The sailors are doing their best to save the ship, but they are don’t succeed. The ship sinks, and wreckage and luggage wash up onto the beach. Naturally, he’s concerned – all this is still in the dream – and he runs to the shore, where he sees the remains of the ship and several bodies. Then he notices a beautiful young woman, lying naked on the sand, facedown but still breathing. He’s a medical student, so he knows what to do. He starts to treat her. Of course, he saves the woman and she revives. Then he finds her some clothes and takes her to his tent on the hilltop. After giving her something to eat and drink they start talking. It’s love at first sight. They say “Wow, you’re beautiful,” and “I love you,” and things like that – all in the introduction to this algebra textbook written in 1722! The author, the hero of the dream, asks the woman, “Who are you? What happened? What’s your name? Why did you suffer this terrible misfortune?” To which she replies, “I can never tell my secret, I can never disclose my identity, but to you, because you saved me and helped me, I’ll reveal that my name is Algebra. At one time, I was actually part of Jewish culture and everybody wanted me and studied me. But in the long years of galut, I was neglected. Nobody took an interest, until you came, my savior, and published this first textbook on algebra.”

The combination of this story with an erotic element demonstrates the powerful passion of those young students trying to broaden their horizons in the early eighteenth century. When they encountered science and philosophy at the university, at the German academy, they felt frustrated and inferior. They asked themselves and the public: why are we not there? Why are we so restricted in our knowledge? Why is our library so limited? If a young student like me

Quote from the text

Conversation on libraries, books and Jewish history

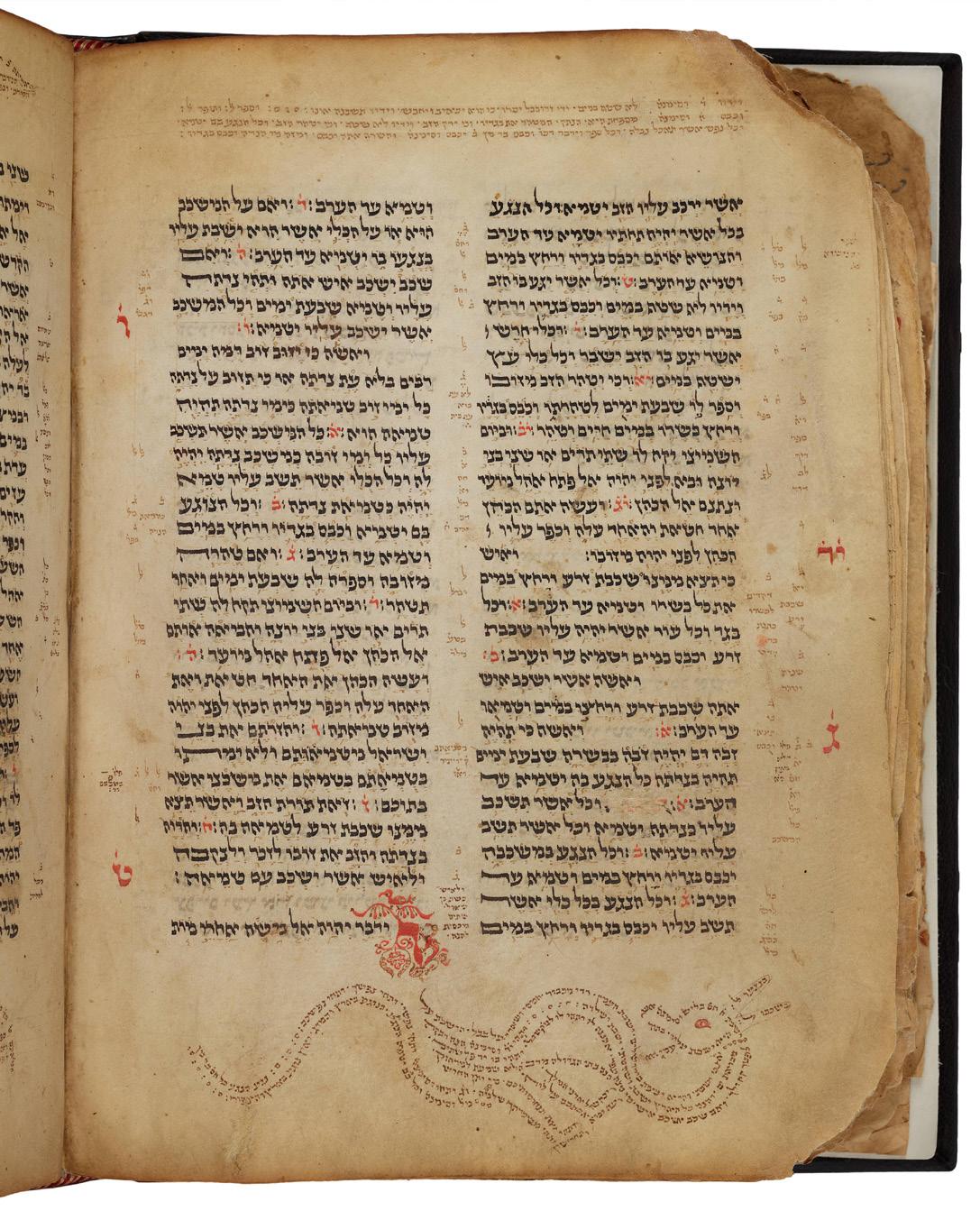

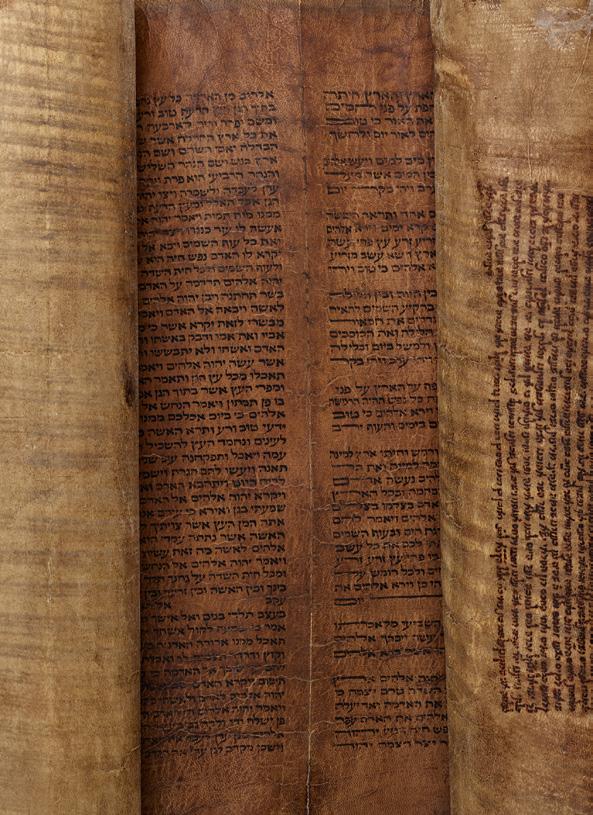

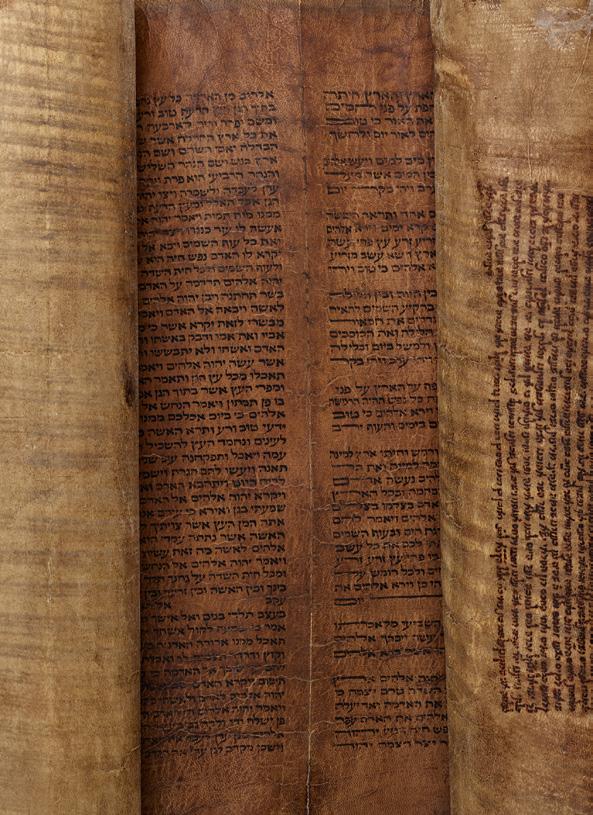

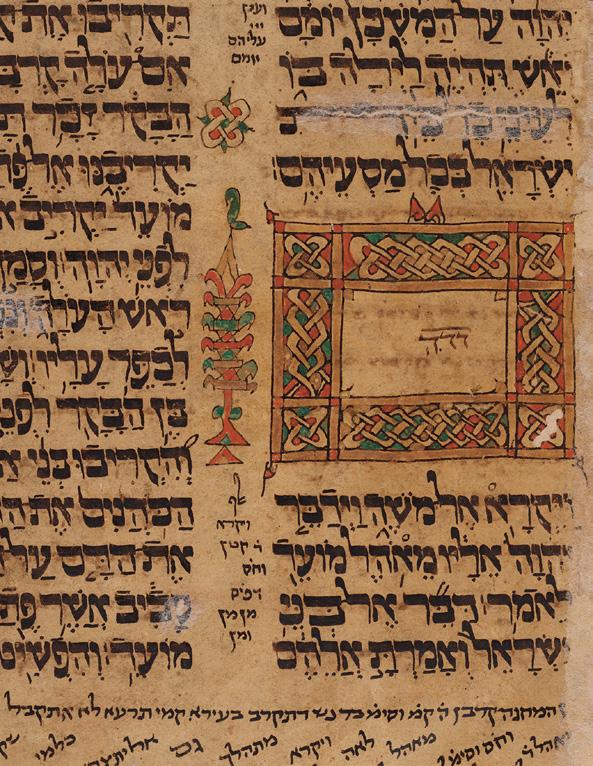

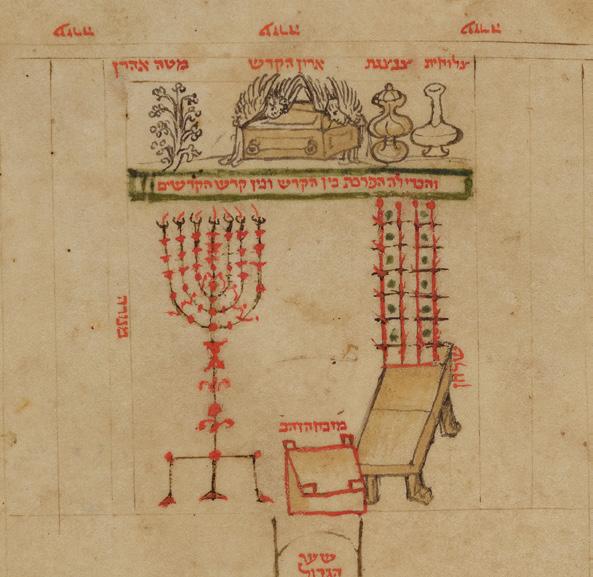

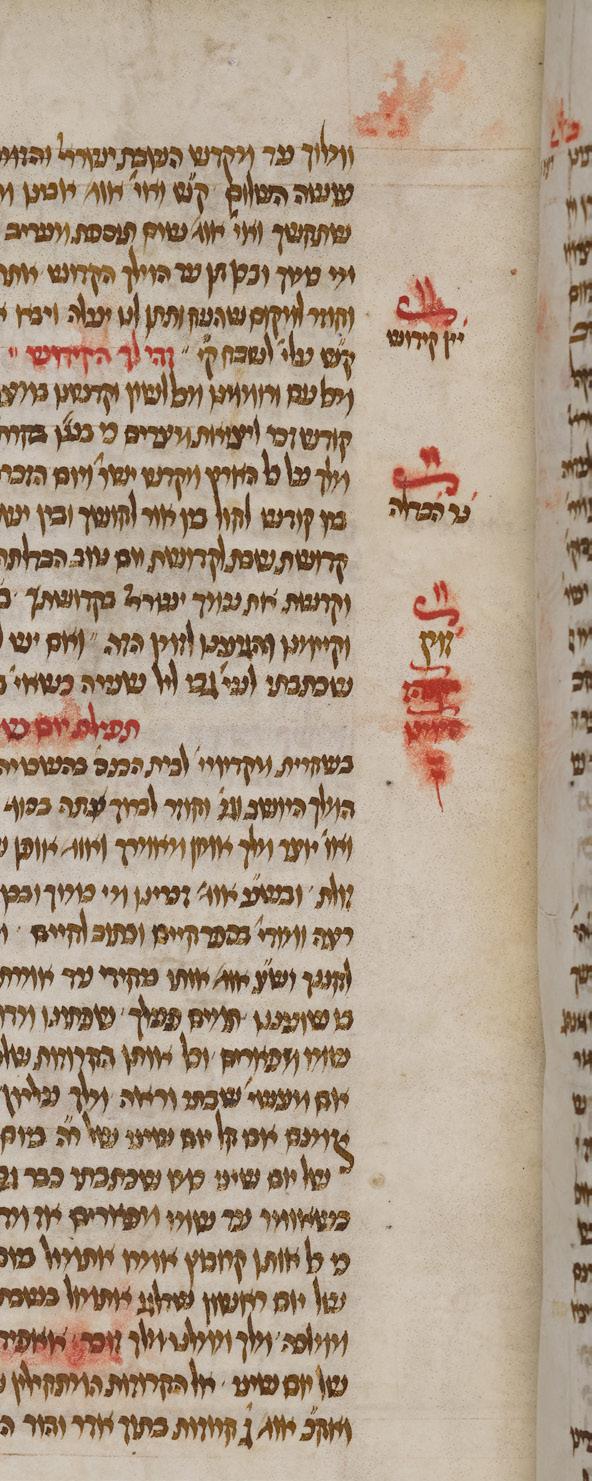

Torah scroll, erroneously attributed to Nissim ben Reuben of Girona (c. 1310 – c. 1375) Spain, 14th century Parchment, height 485 mm National Library of Israel, MS. Heb. 4° 5935

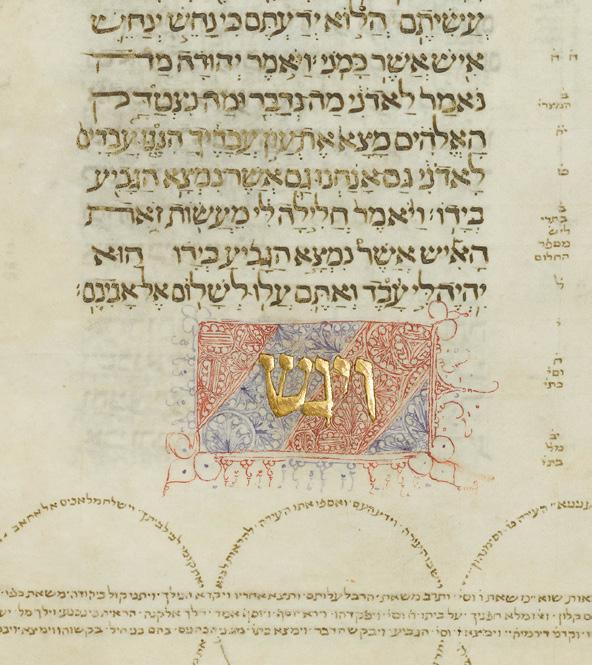

Illuminated Hebrew Bible Spain, 1300

Parchment, 357 leaves, 255 x 205 mm, old elaborately gold-tooled dark brown leather binding National Library of Israel, MS. Heb. 4° 5147

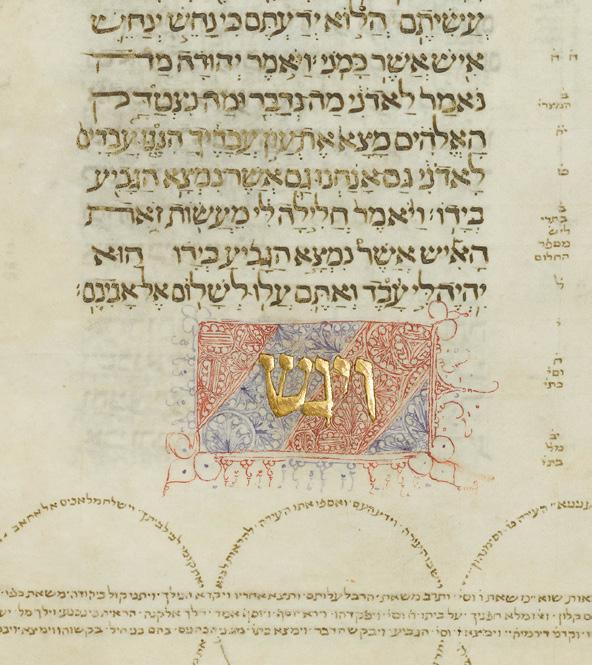

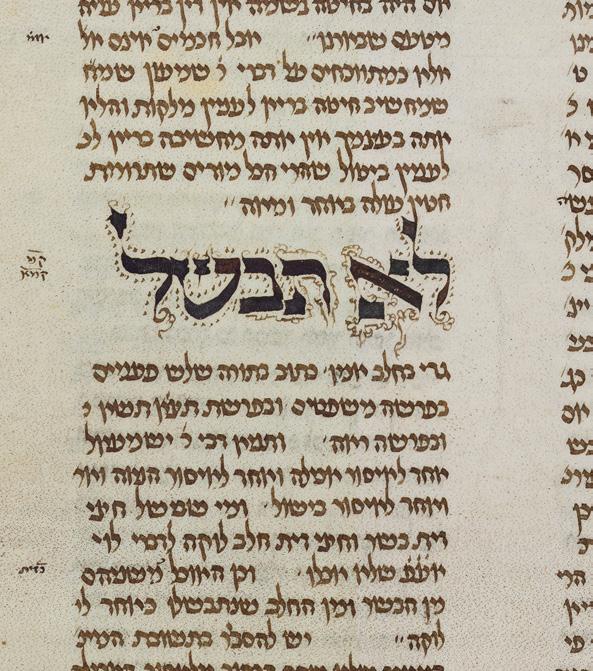

Illuminated Hebrew Bible Spain, possibly Toledo, c. 1400

Parchment, 174 leaves, 345 x 283 mm, modern multicolored elaborately gold-tooled leather binding Braginsky Collection, BCB 377

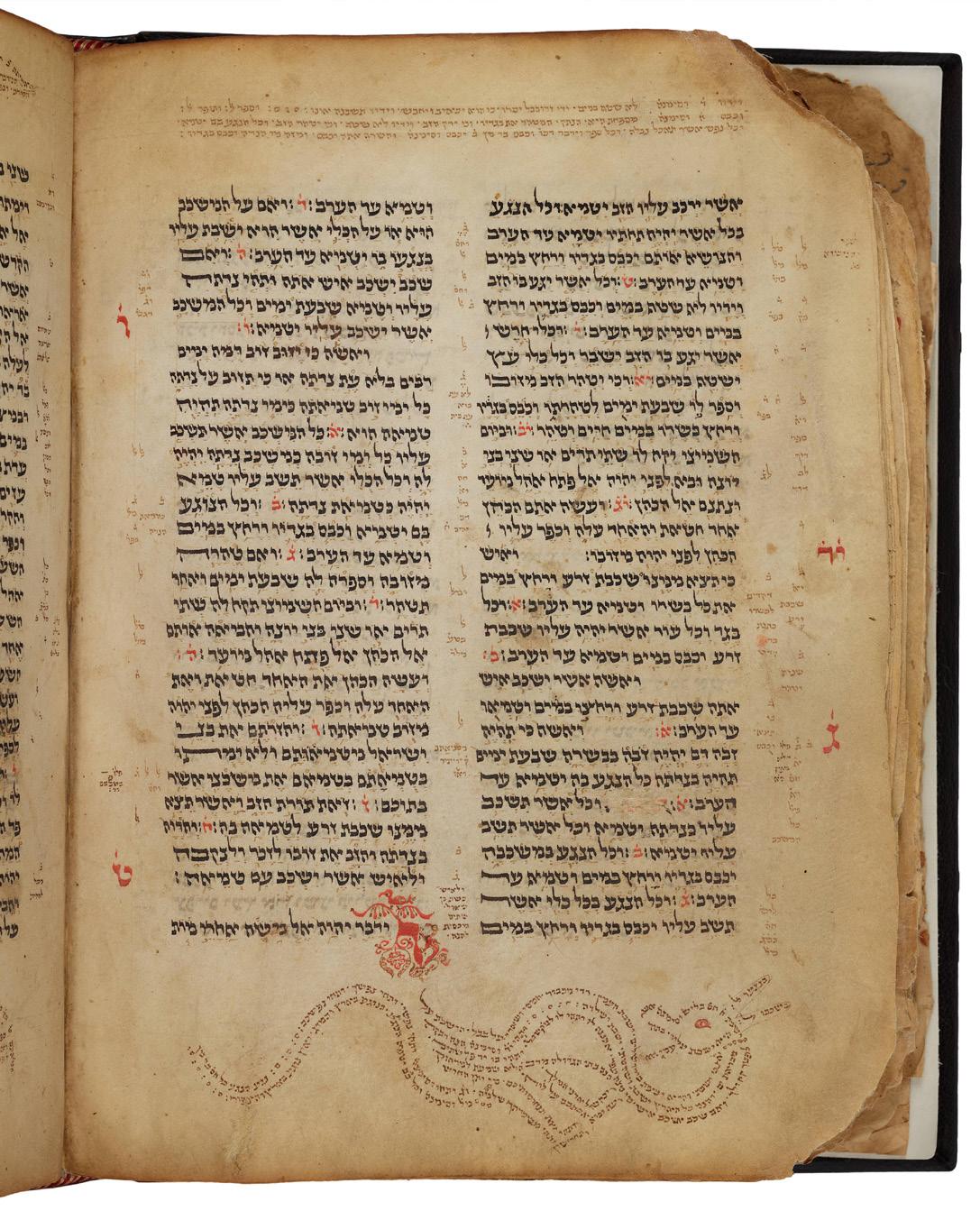

Pentateuch, Exodus 40:36 – Deuteronomy 20:38

With vocalization and cantillation marks

Yemen, early fifteenth century Paper, 167 leaves, 270 x 217 mm, dark red blindtooled leather binding Braginsky Collection, BCB 404

Codification

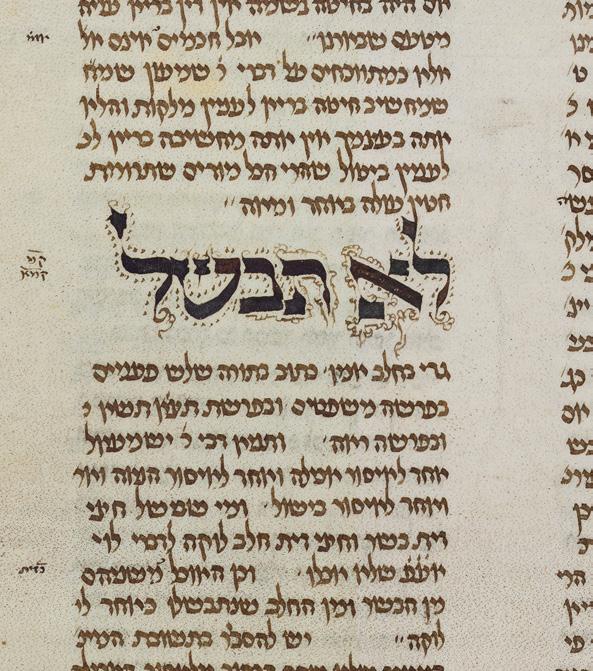

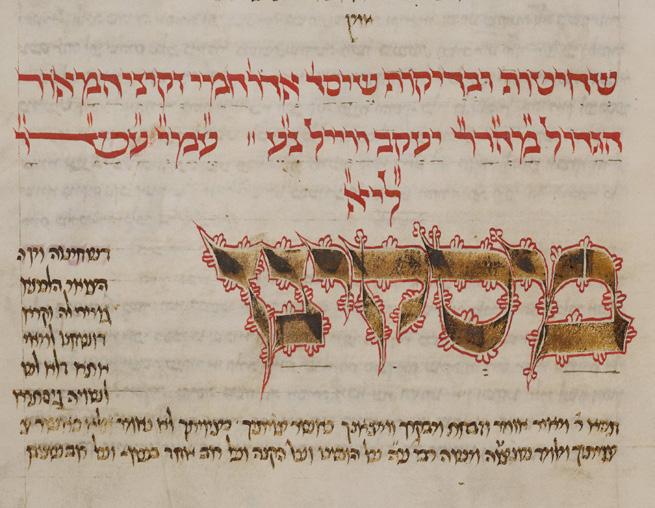

Moses ben Jacob of Coucy (first half thirteenth centur y), Sefer Mitzvot Gadol (Large Book of Commandments)

[Ashkenaz], copied by Hayyim ben Meir ha-Levi, 1288

Parchment, 558 leaves, 310 × 234 mm, modern blind and gold-tooled black leather binding Braginsky Collection, BCB 274

Moses Maimonides (1138–1204), Mishneh Torah (Code of Law), [Ashkenaz 1355]

Parchment, 542 leaves, 520 x 375 mm, old black leather binding Braginsky Collection, BCB 345

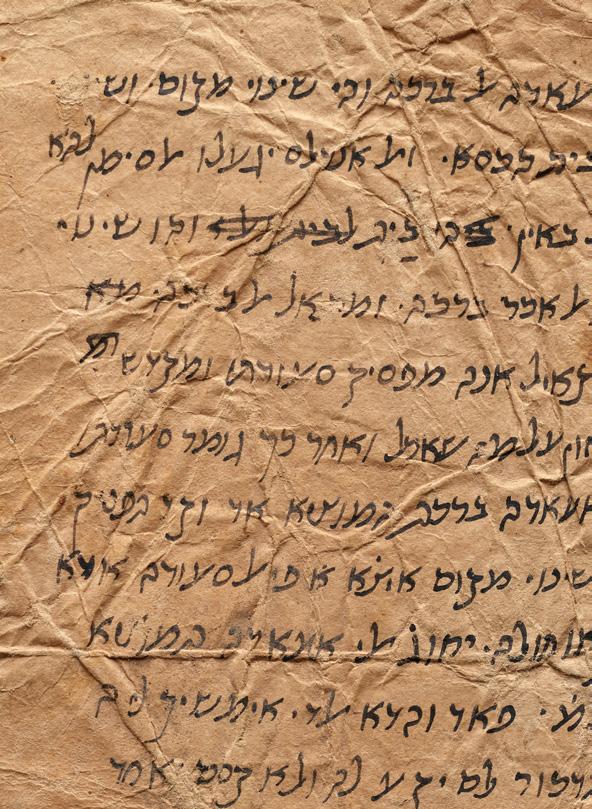

Note by Moses Maimonides (1138–1204) on Isaac Alfasi’s (1013–1103) commentary on Babylonian Talmud tractate Pesahim (probably prepared for one of Maimonides’s classes). [Autograph], late 12th century Paper, 1 leaf, 144 x 107 mm, unbound fragment National Library of Israel, Ms. Heb. 4° 577.10.39

Joseph ben Azriel (fl. 1426), Tzedah la-derekh (Provisions for the Journey)

Zurich, copied by Jehiel, c. 1426 Parchment, two volumes, 152, 130 leaves, 242 x 207 mm, modern half-green morocco binding Braginsky Collection, BCB 406

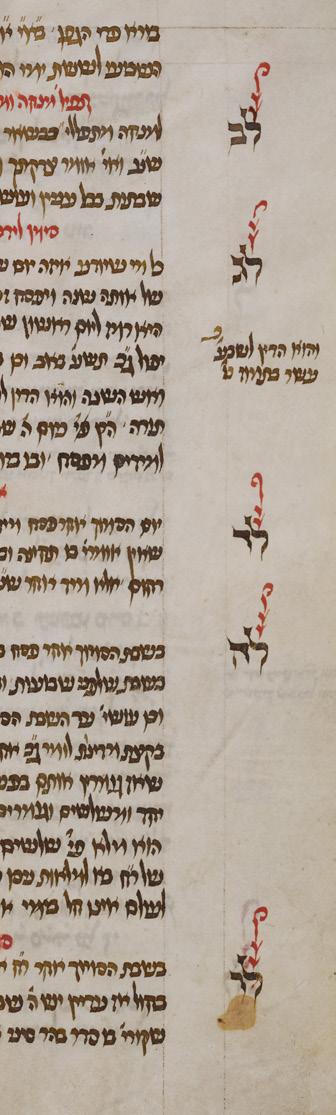

Sefer Minhagim and numerous other religious, rabbinic, and historical texts.

The first section copied by [Jacob] son of Seligman Coburg, Treviso (Italy), completed on 12 Tammuz 5213 (= 1453); the second section copied by Isaac ben Mordecai Halevi, Italy, second half 15th century.

Parchment, 187 leaves, 256 x 189 mm, modern gold-tooled brown leather. The codex consists of two separate manuscripts bound together.

Braginsky Collection, BCB 429

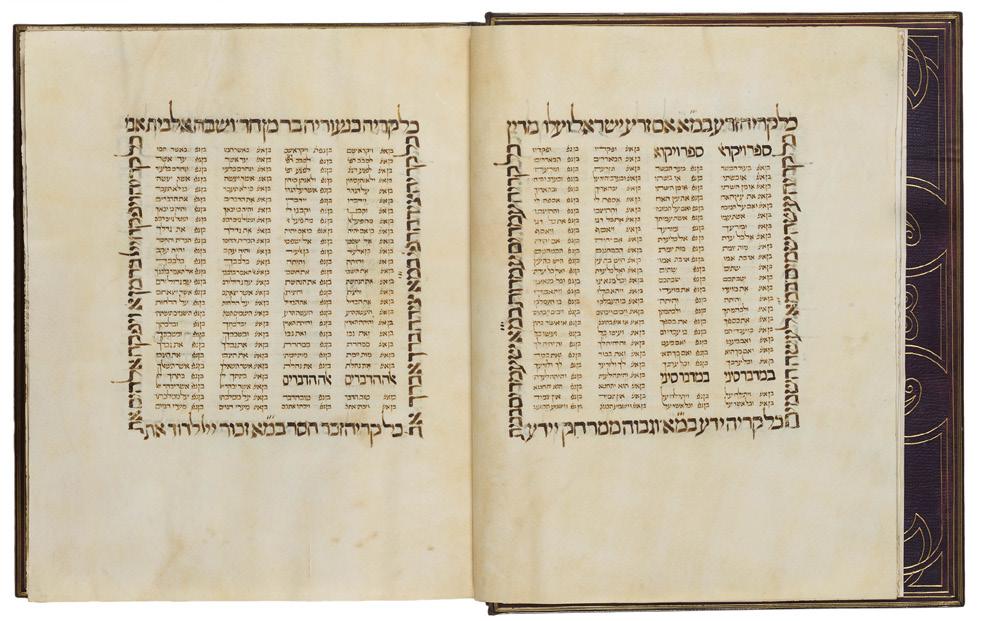

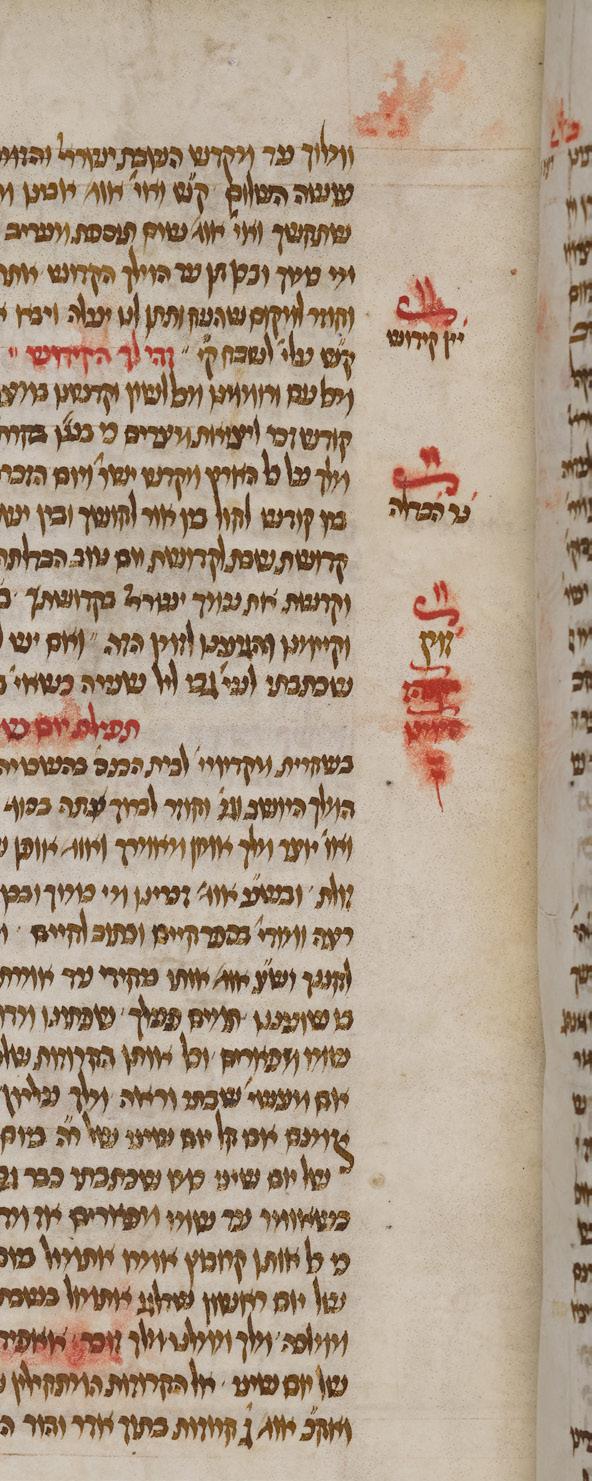

Pinkas (community ledger) of the Jewish community of Frankfurt am Main Frankfurt am Main, 1729–1739 Parchment, 736 leaves, 420 x 300 mm, original gold and blind-tooled brown leather binding, recently restored National Library of Israel, Ms. Heb. 24° 8062

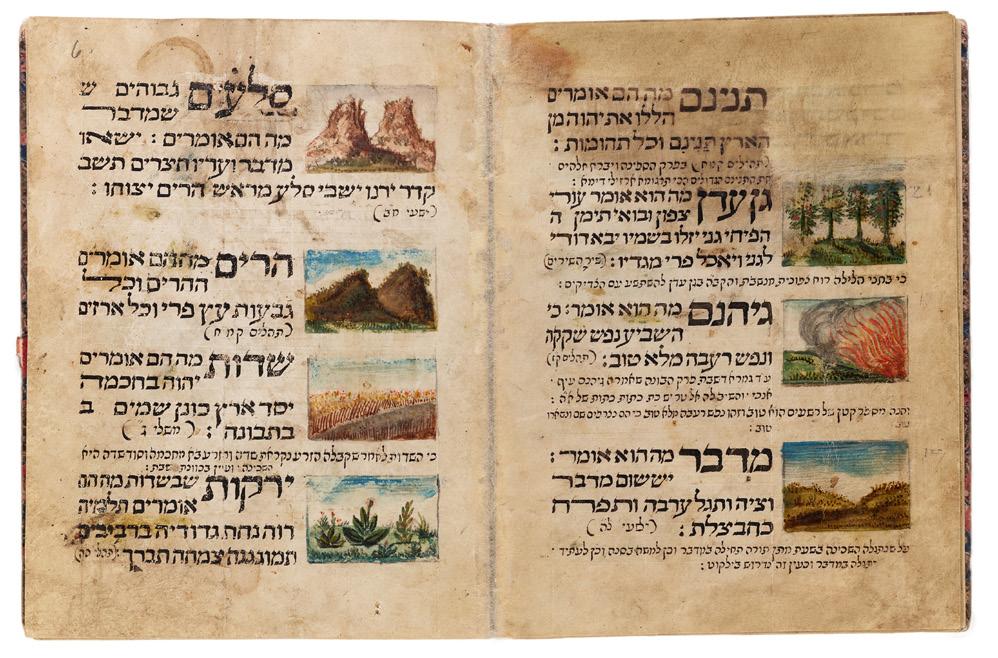

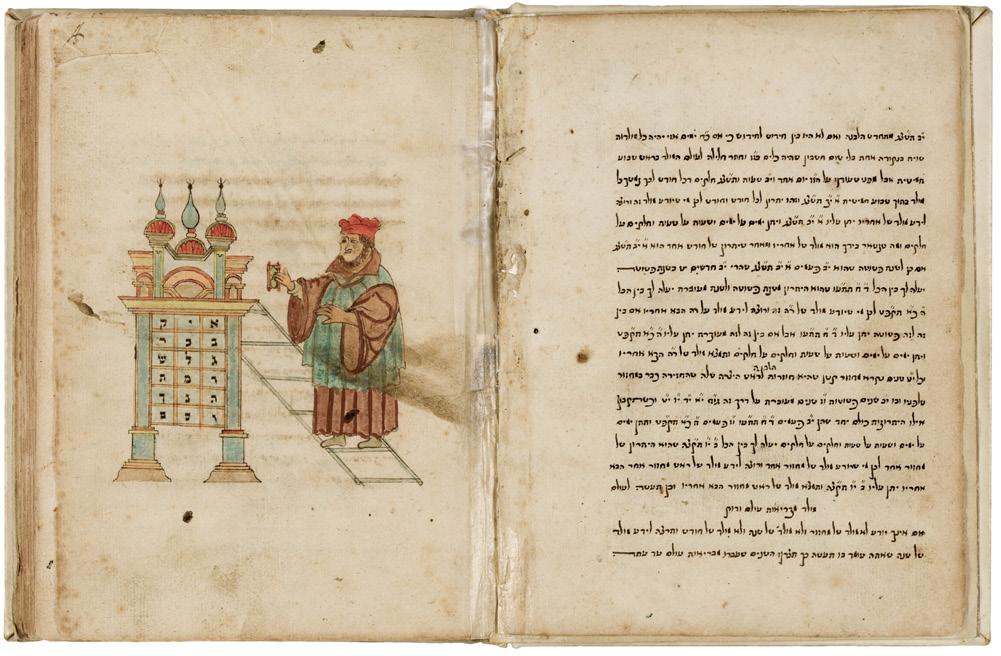

Lo cal co mmunities are a vital aspect of Jewish history. This is especially true in the Diaspora, where Jews have almost always been a minority. Communities provide a safe Jewish space in a non-Jewish environment which is not always friendly. They are characterized by a variety of organizational structures, some loose, some strict, as well as by an array of community services, religious and secular. Communities draw their identity from their minhagim: their religious customs. Many minhagim are recorded in compilations of halacha. More generally, Jewish communities are also distinguished by their book culture, which distinguishes them from non-Jewish communities as well.

A classic compilation of minhagim is the Braginsky Collection’s Sefer Minhagim, collated by Samuel of Ulm (No. 1). The compilation is based on the teachings of Seligman Coburg, the father of the copyist of the manuscript, as well as teachings of contemporaries then living in Swabia, near Ulm. Seligman Coburg migrated from Germany to Italy in the 1420s, residing near Venice, before returning to his native region and eventually settling in Ulm. On fol. 47v, the compiler refers to the current year, 1449, on fol. 39v to the year 1450, setting the date of the composition. While several versions of this minhagim book are known in close to twenty manuscripts, this volume, copied in Treviso, Northern Italy in 1453, is the earliest dated copy. It was written only four years after the original work had been completed. The remainder of the first part of the manuscript

and the entire second part is a miscellany of short pieces about history, ritual law, ethics, midrash and secular poetry, from Ashkenaz as well as Sefarad. Compilations like this, in a single manuscript, typically reflect and represent the taste and interests of the patron who commissioned the work.

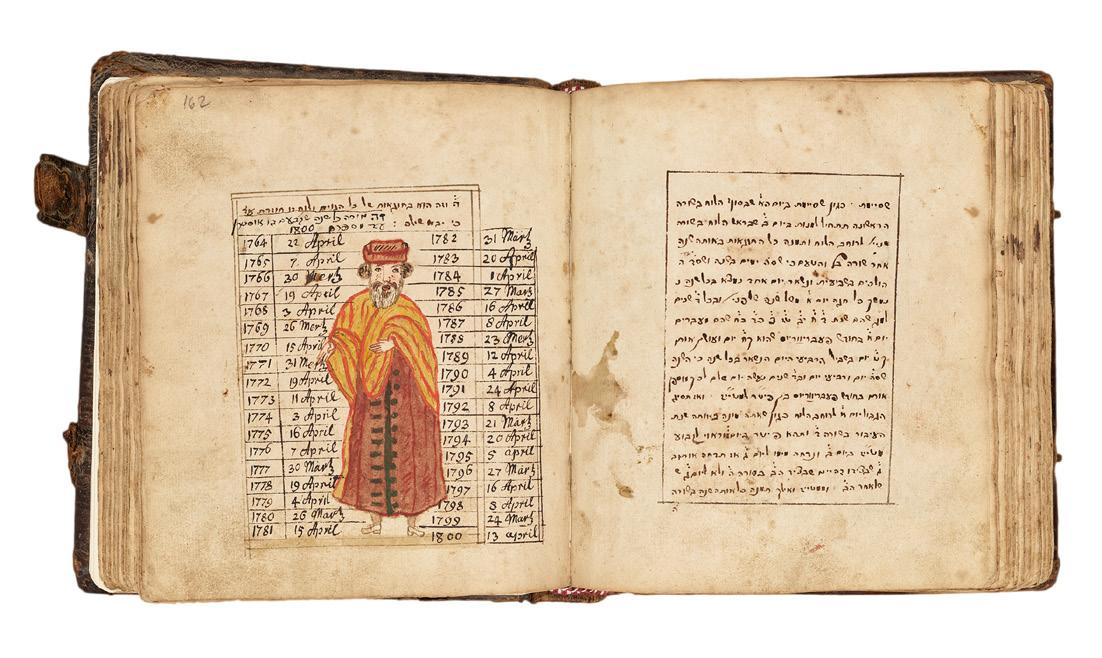

A key manuscript in the collections of the National Library of Israel is a so-called pinkas, or community ledger, from the German city of Frankfurt am Main (No. 2). It was compiled between the years 1729 and 1739. On almost 1500 pages it records the taxes paid by community members and their sundry contributions. Here, members’ names are listed alongside their payments. Administration is a central element of community organization and pinkasim are the primary source of information. They come in various forms, as ledgers of the financial administration of an entire Jewish community or as collections of administrative registers of smaller Jewish societies and organizations. Many pinkasim have illustrated title pages.

It is interesting to note how pinkasim reveal the artificiality of the traditional division between library and archival holdings. Archives hold books and libraries hold archives. The National Library of Israel integrates the holdings of the Central Archives for History of the Jewish People. Together these provide an unsurpassed record of Jewish history in Jewish communities around the world.