Foreword

Ann Deckers

10

Introduction

Tamara Berghmans & Ingrid Leonard

Photography in Belgium: A Game of Magic and Power

Tamara Berghmans & Ingrid Leonard

184

Photography, Nation-Building and Tourism in Belgium in the Nineteenth Century

Herman Van Goethem

190

Urban Photography in Belgium (1839−1900)

Herman Van Goethem

198

The Colonial Gaze Bambi Ceuppens

204

Between Art and Craft: Photography in Exhibitions

Steven F. Joseph

210

Photography and Ethics: Behind Every Image Lie

Myriad Decisions

Kaat Somers

216

Nineteenth-Century Judicial Photography

Paul Drossens

222

Medical Photography and the Ethics of Publishing

Steven F. Joseph

228

Sakala’s Silence: One-Sided Traces of His Life in the Colonial Archive

Lisa Yolanda Lambrechts

234

Revisiting Photographic Heritage: Decolonial and Intersectional Perspectives

Sonia Mutaganzwa

240

Female Pioneers of Belgian Photography

Ingrid Leonard

248

Searching for Missing Images

Pool Andries

254

And Then the Light was Caught: The Oldest Surviving Photos of Belgium

Storm Calle

258

‘A Perverse Speciality’: A History of Pornographic Photography in Belgium (1860-1914)

Leon Janssens

264

About the Authors

265

Dutch Translations Nederlandse vertaling

302

Select Bibliography

Le Daguerréotype, 1839 [1967 replica]

Alphonse-Giroux, Paris

Sliding-box daguerreotype camera for exposures on 16 × 22 cm plates, single lens 1:17 / f 380 mm

Le Grand Photographe, 1840–44 [modern replica]

Charles Chevalier, Paris

Daguerreotype camera for exposures on 16.2 × 21.6 cm plates, with convertible lens system

Bourquin daguerreotype camera, c. 1845 [modern replica]

Bourquin, Paris

Rigid-body daguerreotype camera for exposures on quarter plates, Petzval lens by Alphonse Darlot, Paris

Voigtländer Ganzmetallkamera, 1840–41 [official replica from 1978]

Voigtländer und Sohn, Vienna

Daguerreotype camera for round plates 90 mm diameter, Petzval lens 1:3.7 / f 149 mm

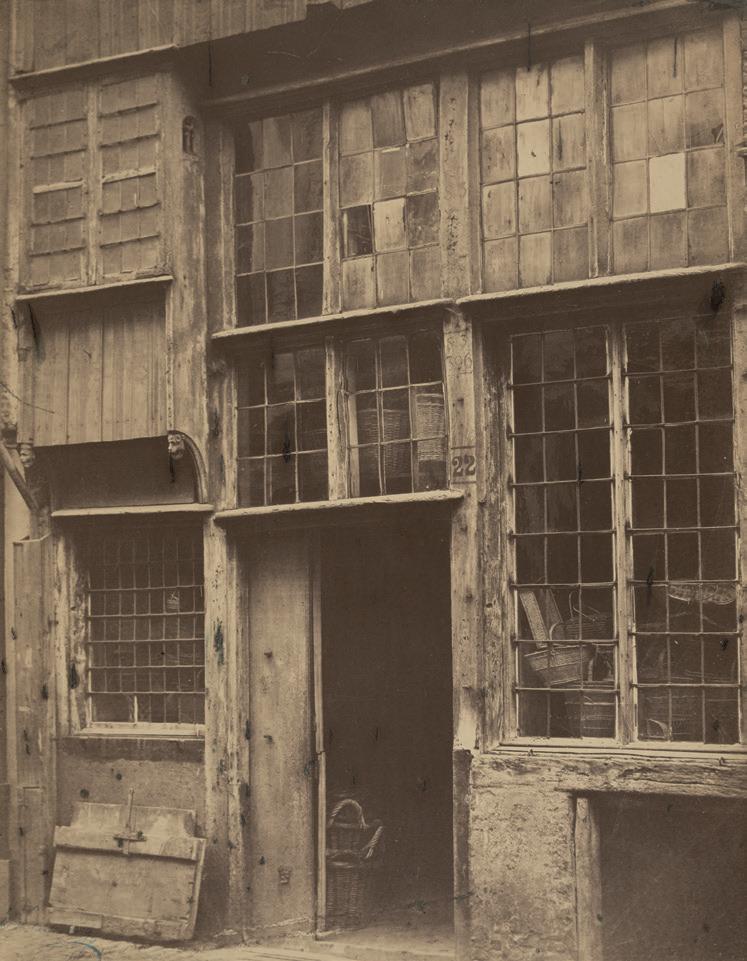

Edmond Fierlants

Marché au Lait 22, basketmaker, Antwerp, 1860

30.8 × 23.8 cm

Porte de Gand, Bruges, c. 1855

Salted

print, 19.5 × 15.4 cm

Egbert Moxham

Pont St-Jean, Bruges, c. 1855

Salted paper print, 22.5 × 17.2 cm

razor-sharp photographs. In 1856, the Frenchman L.P.T. Dubois de Nehaut captured about 30 largeformat outdoor shots of the festivities in Brussels to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Belgian independence. These were not offered for sale, but they have been preserved.7

Not only was the photographic negative now perfect, but between 1857 and 1860 razor-sharp positive prints also became possible, thanks to the use of albumen (egg white). Albumen allowed the image to adhere to the surface instead of becoming absorbed by the paper fibres.

From the late 1850s, numerous photography businesses began to focus on large-format cityscapes. Photographs measuring 50 by 40 centimetres were not unusual. In Belgium, Edmond Fierlants deserves a special mention. In 1860, Antwerp City Council commissioned him to create a series of cityscapes. A similar assignment followed for Brussels and Leuven. Once again, the Middle Ages was chosen as the central theme, alongside baroque church architecture and, in Brussels, the district surrounding the palace. Fierlants was also tasked with photographing old neighbourhoods and buildings that were soon to be demolished. His photographic programme, like those of Moxham and Claine, fitted perfectly into the Belgian national canon, which references the ←

glorious Middle Ages in Flanders and Brabant as part of the country’s origin story.

Urban photography was now in full swing. Fierlants also offered his large, striking photographs for sale. Yet photography was also under scrutiny: would these expensive artefacts not fade? Fierlants died destitute in 1869. In that period, photographers across Europe turned their backs on the grand cityscapes.

1870−1900: Niche Photography and Mass Production

Nevertheless, a profitable market for cityscapes emerged. In Antwerp, Hugo Piéron established himself as a ‘maritime photographer’ from the 1870s onwards, capturing images of the old quays and waterways that would soon vanish. Photo series by Florent Joostens documenting the demolition of Antwerp’s ramparts also enjoyed enduring success. All this proved that nostalgic niches could thrive. Photographs of ruins, such as the abbey of Villers-la-Ville, probably fared well too.

A market for cheap photographs also developed. As early as the 1860s, stereo photography broke through. Two identical images measuring approximately 6 by 6 centimetres were glued, side by side, on to an oblong piece of card. People then

During the nineteenth century, erotic pictures evolved from a luxury item to a product that a larger group of people could afford. This process of democratisation continued into the early twentieth century. Indeed, the production of photographs itself also became increasingly accessible. A particularly illustrative case study is that of Frans Joseph Hector Hannequin.

The Frenchman ran into trouble in the summer of 1909 when someone sent a letter of complaint about him to the Antwerp police. The complainant alleged that a 25-year-old man was selling lewd postcards to underage boys. Furthermore, the complainant claimed to have overheard the seller saying that he made the postcards himself. The investigation revealed that Hannequin had asked a certain Isidoor Rijs to develop several photographs. Rijs told the police that Hannequin had asked him to develop three dozen photographs of his sweetheart. At least two of these prints are preserved in the court file.15 The photographs depict Hannequin and his girlfriend in various sexual poses while gazing directly into the camera. These images serve as rare evidence of the role erotic photography played in people’s lives between 1850 and 1914. It is also noteworthy that we find remnants of this phenomenon within an institution that, at the time, sought to combat such photographs.16

NOTES

1 State Archives of Belgium, Vorst, Court of Appeal of Brussels. Series II. Files relating to criminal appeals, 1811−1884, file 1733, letter from the royal prosecutor Alexis Hody to the prosecutor general, 30 July 1863, no. 206.

2 Jonathan Coopersmith, ‘Pornography, Technology and Progress’, ICON 4 (1998), 98−99; Lisa Sigel, Governing Pleasures: Pornography and Social Change in England, 1815−1914 (New Brunswick, 2002).

3 Brussels Court of Appeal, letter of 30 July 1863, no. 206.

4 Brussels Court of Appeal, letter of 30 July 1863, no. 206.

5 Raisa Adah Rexer, The Fallen Veil: A Literary and Cultural History of the Photographic Nude in Nineteenth-Century France (Philadelphia, 2021), 46.

7 Liesbet Stevens, Strafrecht en seksualiteit : de misdrijven inzake aanranding van de eerbaarheid, verkrachting, ontucht, prostitutie, seksreclame, zedenschennis en overspel (Antwerp, 2002), 103−105.

8 Stevens 2002, 286−290.

9 Brussels Court of Appeal, file 1782, Pro Justitia 20 October 1863, no. 848.

10 Alexandre Dupouy, Joyeux Enfer. Photographies pornographiques 1850−1930 (Paris, 2014), 12.

11 Coopersmith 1998, 99.

12 State Archives of Belgium, Brussels, HA Brabant, 1302, file 2441, Enrichetta’s order letter dated 24 October 1903, no. 202/4.

6 For more information on this battle, see Leon Janssens, ‘Pornography on Rails: Trains and Belgium’s “War on Pornography”, 1880–1891’, Journal of the History of Sexuality 32, no. 3 (2023), 269−287.

13 For an idea of the enormous array of 19th-century pornographic products, see Bert Sliggers, Vouwen, klappen, trekken,

draaien. Pornografisch drukwerk voor de ongeletterde (Zutphen, 2024).

14 State Archives of Belgium, Brussels, Brussels Public Prosecutor’s Archive, folder 193, letter from the royal prosecutor to the prosecutor general, 6 August 1904, unnumbered document.

15 State Archives of Belgium, Beveren, Archive of the Criminal Court of Antwerp, file 5135.

16 For more on the history of pornography in Belgium, see Leon Janssens, Tussen angst, afkeer en wanhoop. Een emotionele geschiedenis van de strijd tegen pornografie in België (1880–1910) (KU Leuven, 2024). This PhD dissertation was made possible by a grant from the Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek. https://lirias.kuleuven. be/4093446&lang=en.