6 minute read

Four | A Research Student

from Digging Deep

I returned to Cambridge in October to begin my doctoral research. The state scholarship paid all my expenses and Eric Higgs was my supervisor. When I asked him for his advice on a suitable topic, his reply came in two words, “Try Norway”. I went as far as buying a Norwegian dictionary but my enthusiasm for that country soon ran into the sand. Meanwhile, Colin Renfrew was planning to excavate at Sitagroi in Greece and Paul Mellars was tracking down the stone tool assemblages of the Mousterian Neanderthals in the Dordogne. Barry Cunliffe remained so distant that I am not sure what topic he chose to pursue. My own plan was to track down assemblages of animal bones from European Neolithic sites in order to reconstruct their economies. Leading questions involved the ratio of domestic to wild animals, which species were raised and which were hunted, was there a pattern to how cattle or sheep or goats were selectively killed, were they raised for meat or traction, what do the species tell us of the environment. I began by looking at likely sites in Britain that included a visit to Avebury to see Isobel Smith, but before long, began listing possible museums and departments on the continent that might have collections I could study, and heard back from Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland. It soon became apparent that to get to these institutions, I would need a car. But having relied entirely on my NSU Quickly for transport, I had no driving licence, so I booked in for driving lessons in Cambridge. Rugby too dominated the term, though being a blue, the stress was greatly reduced. I missed three games through injury, but we were again successful at Twickenham, by 14-0. Following this game, I was asked if I would be available to tour New Zealand with the England team the following year, and I was selected to travel down to Gloucester for the 2nd England rugby trial. I was beginning to think and hope that perhaps I might one day be an England international. Dr Lucan Pratt was then the Senior Tutor of Christ’s College and a fanatical supporter of University rugby. If a candidate for admission had a strong rugby record, his chances of success rose significantly. In early November, I was enjoying a cocktail party in his college and he confided that I should apply for a Research Fellowship in Christ’s. Looking back, I must have been completely idiotic not to have done so. It would have given me all the benefits that come with a college fellowship: rooms in college, dining privileges, financial support not to mention the academic mana. Colin was then, for example, a research fellow at St. John’s. I think I declined the invitation through misplaced loyalty to St. Catharine’s. That was a crossroads where by turning right rather than straight on, I think I would have had a quite different career.

The Lent term of 1963 was bitterly cold. My exercise included skating on the River Cam. As the term progressed, my plans for a research trip to the continent matured. My itinerary began in Brussels, and then the Biologisch-Archaeologisch Institute in Groningen, where Anneke Clason told me that she had some interesting samples to look at. Then, it was to Schloss Gottorf in Schleswig before going to the Zoologisches Museum in the University of Zurich. The only issue now was a vehicle. My mother identified a Ford Escort 100E estate car on a friend’s advice, costing £200.00, far beyond my means. Again, the trustees of Uncle Strachan’s bequest lent a hand and the car was mine for £160.00. It had a major plus. The back seat let down flat to allow me to extend a mattress and sleep there. This was to prove a great benefit on my travels, but I still had to pass a driving test and obtain a licence. Until then, I could only drive if someone with a licence was with me, so on the 24th March, Richard and his wife Jane suggested that we three go up from their flat in Welwyn Garden City to Cambridge to give me driving practice. At the last minute that Sunday morning, Richard suggested that he invite Pauline, who worked in his office. She agreed on the telephone and we went over to collect her in Hertford Heath. We four enjoyed a lovely spring day, admiring the daffodils on the backs, lunch in a Chinese restaurant and a movie. Pauline (Polly) and I were married the following year.

My initial search for large, well-provenanced samples of faunal remains in England returned little of value. In those days, animal bones were not retained and analysed as they are today. Indeed, at Verulamium they were not kept for any form of analysis. I paid visits to various museums, and looked at some small collections but they were all insufficient for my purposes. So I looked increasingly to the continent, and having heard of the samples I needed from Professor Magnus Degerbøl in Copenhagen University, applied for a Danish Government scholarship. An interview at the Danish embassy ensued and on the 1st April I heard by letter that I had been successful. However, Degerbøl soon wrote that all the collections would be unavailable for a year because they were moving into a new museum. On the same day, I had my first acquaintance with a new-fangled device known as a computer. Chris Petrie, an expert in the Shell Department of Chemical Engineering, helped me with a program that would rapidly provide me with the means, variations and confidence limits of bone measurements. This computer cost £60,000. The new Ferranti Jupiter on order cost about £1,000,000.

On the 9th April, I cleared a vital hurdle by passing my driving test. I was now free to venture onto the continent and just eight days later I took the ferry to Ostend and ended up in the home of Mr Jean Verheyleweghen in Brussels. He had excavated at the Neolithic flint-mining site of Spiennes. Unfortunately, again there was insufficient material. So I drove on, again by prior arrangement, to Groningen and the Biologisch-Archaeologisch Institut where I had been informed by Dr Anneke Clason that she had available, the large samples that I so badly needed. I settled down happily in the Groningen camping ground and spent all day working on a sample from the site of Vlaardingen. At last I had what I needed. But it was a false dawn. Dr Clason began to show anxiety at my enthusiastic hours poring over the bones, and after a week or so, told me that I should move on and not use them in any way, they were her sole responsibility. Disappointed, I went to see the Director, Dr Waterbolk, in the hope of finding a resolution but to no avail. I had no option but to move on again.

My next port of call was the Schleswig Museum. I drove across north Germany on a rainy Friday to arrive outside the magnificent Schloss Gottorf, a stately castle on an island with an impressive wooden gateway well locked after closing hour. I knocked on the little postern door and was admitted by a watchman. He rang the director and gave me the telephone. The voice at the other end welcomed me with the news that the guest suite was at my disposal. The prospect of a night in the car evaporated as I was led along a long corridor to total comfort, a hot shower and equipped kitchenette. I could have stayed there all summer had the collections suited my purpose, but they didn’t. So 48 hours later I set off on my last throw of the dice: Switzerland. Two days and 657 miles later, I arrived in Zurich and found a campground on the lake shore. The following day I arrived at the Zoologisches Museum of the University of Zurich to meet Dr Hanspeter Hartmann-Frick. He was a schoolteacher with an interest in identifying animal bones, and a major publication under his belt from the site of Eschner Lutzengüetle in Liechtenstein.

I had fallen on my feet. Hanspeter unreservedly welcomed me, and took me up into the Estrich, the museum roof space where were stored box upon box of animal bones from the Swiss Neolithic lake village of Egolzwil 2. My spirits were high. The director of the Museum, Hans Burla, gave me the run of the institution and asked Marco Schnitter, one of his junior colleagues, to show me the ropes. He took me to the University Studentenheim, where I could buy breakfast, lunch and dinner. I

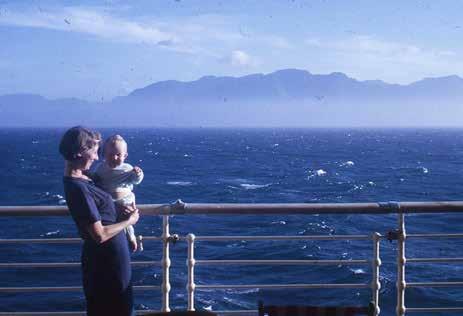

At last, our first view of Aotearoa, the land of the long white cloud, New Zealand. This is the east coast of the North Island. We soon rounded Cape Palliser to dock at the Pipitea wharf in Wellington.