4 minute read

Three | A Cambridge Undergraduate

from Digging Deep

Dad advised me that at Cambridge, one works in the morning and the evening, and plays in the afternoon. I was a serious-minded 19-year-old when Mum and Dad drove me up on the 4th October 1959. I had two ambitions. My wider family had a consistent record of excelling academically, and I felt pressure to do well in my exams. I also badly wanted to be selected to play rugby against Oxford University, and thus become a Cambridge blue. This ambition was sharpened when, during my first term, brother Richard was given his Oxford blue playing against us and winning 9-3. My college, St Catharine’s, found digs for all first year undergraduates except scholars. Mine were at 36, Langham Road, where we met my landlady Mrs Murkin and her son Bernard. I was given the ground-floor room facing the street for my living room, and the bedroom above it. The house was somewhat damp and despite an ancient ceramic vessel for hot water in my bed, I soon developed rheumatic aches. Mrs Murkin had to keep a time sheet showing that I was in residence before 10 pm each night unless I had a valid reason approved by my tutor, who had the remarkable name of Augustus Caesar. I had breakfast in my digs supplied by Mrs Murkin, and lunch and dinner in hall. The latter was a formal occasion requiring a jacket, tie and my college undergraduate gown.

James Neill and Co. on the corner of King’s Parade and Silver Street supplied my college blazer, a gift from my grandmother that I still wear on occasion. Mum and Dad gave me my scarf and gown. There were about 100 freshmen in my year, all young Englishmen. Through rugby training and chatting over lunch, about half a dozen of us became close friends, and met from time to time in the digs of Richard Walduck for tea and crumpets, because he lived closest to college. As a grammar-school boy I had mixed feelings about the effortless superiority I had encountered from public schoolboys in Surrey county rugby circles, but I found my new friends who came from Harrow, Tonbridge, St Paul’s, and Eastbourne good company. We were warned by our Senior Tutor not to form cliques, so we called ourselves “the clique”.

Cambridge was then in its twilight years as a bastion of Victorian antipathy towards women. My tutor had a proud boast that since the college’s foundation in 1473, the only woman to have dined in hall was Queen Victoria, not because she was the Queen Empress, but because she was the Chancellor’s wife. There was a rigid regulation banning women in college beyond 10.00 pm. If one escorted a lady past the porter’s lodge after 10.00 pm there was a fine of one shilling a minute. If after 10.30 pm, you had a date with your tutor to explain. College gates were closed shut at 10.00 pm, and anyone locked out had the option of trying to climb in somehow undetected, or incur the wrath of your tutor by knocking on the front door and being reported.

Lectures began during my first week, and took place in the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology. I soon met up with Barry Cunliffe, who had been given a choice set of rooms in the second court of St John’s. We struck up a good friendship and I was often there. Our subject matter during the first term ranged from palaeolithic archaeology to ethnography and social anthropology. I was committed to at least two essays a week, which were assessed when I met my supervisor. Early that term I made my way to the third court of St John’s and climbed the staircase to knock on the door of Glyn Daniel’s rooms. I asked him if he would supervise me. “Are you a Johnian?”, he responded. Of course I wasn’t, and he declined to assist. I did, however, have the good fortune to chat with Paul Ozanne, a third year archaeologist in my college, who urged me to seek out his wife Audrey in the Archaeology Department. She took me under her wing. We two met at least once a week, when I would read her my latest essay before she commented. I soon fell into a routine. Lectures and reading during the morning, then cycling down to my college for lunch before heading for the rugby ground or the squash courts. By 4.00 pm I would be in the library before dinner at 6.00 and then, usually, cycling back to Langham Road to read or write before turning in hardly ever later than 10.00 pm.

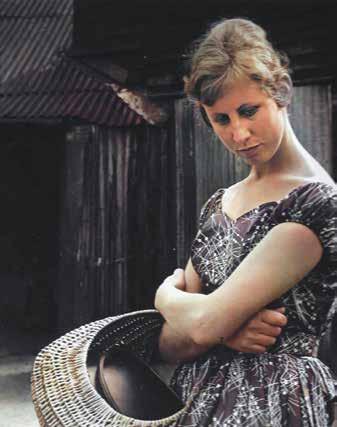

This routine did not extend into all the weekend. On the 24th October a friend from the Institute, Hannah Williams, came up for the weekend and we went punting. Barry Cunliffe hosted another Institute friend and the four of us had dinner and wine in his rooms that evening. While my academic work progressed smoothly, rugby didn’t. Two other freshmen in my college who played in my position, hooker, were preferred to me and I languished in a lower college team. My progress was also derailed when, only three weeks into the term, I arrived back at Langham Road to find that Mrs Murkin had died. I had to find alternative accommodation, and did so before I went down with a bad case of flu. When I arrived at my new digs following my recovery, I found that my landlady there had also died. I then tracked down a perch in 96, Mowbray Road where Miss Nash made me welcome. It was a warm and most comfortable home for the rest of the academic year but so far out of the centre of town that I was given a permit to use my NSU Quickly by the Motor Proctor.

The end of the term brought my first college bill for accommodation, subsistence and incidentals. The entirety was met by the County Major Scholarship given me by my county, Surrey. It even had a clause stating that there was sufficient in the grant to cover my costs during the vacations. My Uncle Strachan had died in 1958. He established a trust in his will, of which I was a beneficiary. On the 8th January 1960 I was given the first of many instances of generosity, and set

October